1.1. Research Context and Background

In the contemporary business environment, the importance of striking a balance between professional responsibilities, personal well-being, and sustainability principles is increasingly recognized. The expanded availability of digital technologies and the proliferation of remote work models following the recent global health crisis have prompted both organizations and employees to re-examine conventional frameworks of work time and location. Concurrently, intensifying pressures related to productivity and market competitiveness have been linked to elevated levels of stress, which may contribute to long-term adverse effects on the physical and mental health of employees. Furthermore, the promotion of sustainable lifestyles within the corporate context extends beyond environmental initiatives to encompass a commitment to human resource management, aiming to foster enduring habits that support employee health and well-being.

Research indicates that employees who are afforded greater autonomy in organizing their work, coupled with clear boundaries between their professional and private lives, report higher levels of satisfaction, lower rates of burnout, and enhanced motivation and engagement [

1,

2,

3]. Such an approach not only reduces employee turnover and the associated replacement costs but also enhances the organization’s reputation as a socially responsible employer [

4]. Concurrently, sustainability entails reducing the carbon footprint associated with commuting, promoting digital collaboration tools, and ensuring the responsible use of resources [

5]. Balancing work and well-being while promoting environmentally friendly practices can create a synergy between individual health, organizational efficiency, and societal sustainability.

This paper systematically examines the multidimensional impact of remote work intensity on four key outcomes: perceived stress, self-assessed health, work productivity, and the adoption of sustainable practices among employees in the IT sector. The primary objective is to formulate evidence-based recommendations for achieving a lasting equilibrium between work, well-being, and sustainability [

6], acknowledging the complex and sometimes contradictory effects that different demographic groups may experience.

1.2. Data Access and Variable Measurement

1.2.1. Data Context and Measurement Approach

The survey utilized in this research was not exclusively designed for the topic “Evaluating the Impact of Remote Work on Employee Health and Sustainable Lifestyles in the IT Sector.” This survey was part of a broader investigation into remote work, specifically examining the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on employees in the IT sector. Nevertheless, the justification for its use is based on the significant sample size (

n > 1000) and the quality of the data, which was affirmed in a previously published study using the same dataset [

7].

The use of pre-existing, large-scale datasets, even if they require variable transformation, is warranted in the context of several key limitations within the current state of research on remote work:

First, the field is saturated with studies that rely on self-report data. While necessary for measuring subjective experiences such as stress or satisfaction, such data are susceptible to recall and reporting biases [

8]. Utilizing a large sample, as in this case, represents a valid strategy for increasing statistical power and mitigating some of these issues, even when employing proxy measures.

Second, the literature is dominated by cross-sectional studies, which provide a point-in-time assessment but cannot establish causal relationships [

8]. Actual longitudinal studies, featuring multiple waves of measurement, are scarce but are crucial for understanding the long-term effects of remote work [

9,

10]. Therefore, the cross-sectional design of this study is typical for this field, and its limitations, rather than being overlooked, should be explicitly stated to provide an impetus for future research.

Third, there is a pronounced lack of standardized and validated measurement scales for key constructs related to remote work [

11,

12]. Many studies rely on ad-hoc instruments or adapted measures, which complicates the comparison of results and the generalizability of findings [

12]. In this light, the approach used in this paper—forming composite scales from existing items—is not an anomaly but rather a reflection of the current state of the field. The methodological contribution of this work, therefore, is not only in testing a substantive model but also in demonstrating the utility of carefully constructed proxy variables from large secondary datasets, which presents a valuable approach for other researchers facing similar constraints.

Accordingly, the current state of research in this area is characterized by several key limitations that justify the use of existing, large-scale datasets, even when they necessitate the transformation of variables.

1.2.2. Operationalization of Variables and Measurement Fidelity

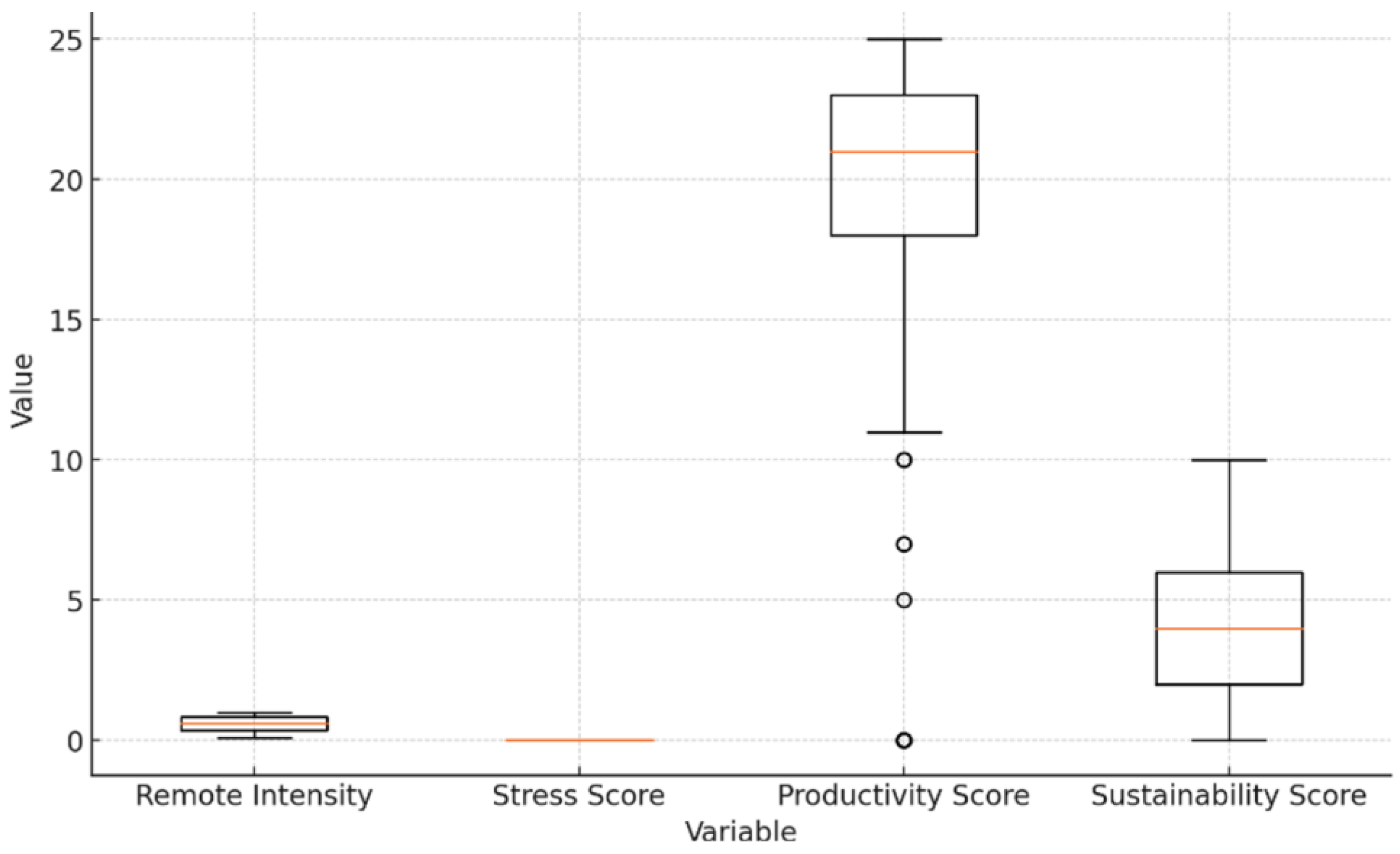

Five key variables were defined: Stress_Score, Productivity_Score, Sustainability_Score, Remote_Intensity, and SelfRatedHealth. The internal consistency of the composite scales, confirmed by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α ≥ 0.746), provides a solid initial foundation for their reliability. However, the validity of these measures can be further reinforced by theoretically linking them to established constructions and scales from the recent literature.

Stress_Score: This variable is defined as a “reconstructed PSS-like scale of perceived stress” (Perceived Stress Scale), based on the summation of items from the survey questionnaire (Q24_1-7). This represents a conceptually grounded approach. Its validity can be substantiated through comparison with external benchmarks. For instance, a recent study developed and validated a brief, 5-item “Short Remote Work Stress Scale” (SRWSS), which includes items such as Imbalance, Overworking, Miscommunication, Inactivity, and Insecurity [

13]. The items used in our study (Q24_1-7) encompass similar domains of stressors—such as technostress, social isolation, and work-life interference—that have been identified as critical in the broader literature [

14].

Productivity_Score: This measure is based on the self-assessment of various aspects of productivity. This is a common yet controversial approach. The literature reveals a profound dichotomy between subjective (self-report) and objective measures of productivity. Studies relying on self-assessments frequently report an increase in productivity during remote work [

15]. Conversely, studies using objective data from IT firms, such as analyzing system logs or tracking the number of completed tasks, sometimes indicate a decline in productivity. For example, it has been shown that working from home during the pandemic led to a productivity drop of 8% to 19% [

16]. It is therefore crucial to explicitly position the

Productivity_Score as a measure of

perceived productivity. Perceived productivity is a valid psychological construct, as it influences job satisfaction, motivation, and employee behavior, making it a valuable dependent variable irrespective of objective output [

17].

Sustainability_Score: The use of selecting the “Work from Home” option as a proxy for environmentally friendly practices is an innovative yet indirect approach [

18]. Its precision requires careful framing. The literature on Pro-Environmental Behavior (PEB) offers a more robust conceptual framework [

19]. PEB encompasses a wide range of discretionary actions, including conserving energy, reducing waste, and recycling [

20]. The proxy used here primarily captures the structural environmental benefit of remote work—the reduction in emissions from the absence of commuting (low-carbon production) [

21]—but not the discretionary PEBs that employees may (or may not) engage in at home.

This is a critical limitation of our measure. It is also essential to note that remote work can have adverse

“rebound effects,” such as increased household energy consumption and greater reliance on digital infrastructure, which this proxy does not capture [

22,

23]. Acknowledging these nuances is critical for the correct interpretation of the results and for ensuring the transparency of our methodological approach.

Remote_Intensity: The calculation of this variable as the proportion of remote work within a standard work month represents a clear and continuous measure. This approach is fully aligned with the latest research, which is moving away from a binary distinction (office vs. remote work) and instead examining “Remote Work Intensity” (RWI) [

24]. Available studies indicate that there is often a non-linear or “dose-response relationship” between RWI and outcomes, with a hybrid model frequently emerging as the “sweet spot” [

25]. The

Remote_Intensity variable used is therefore excellently positioned to test for such curvilinear effects.

SelfRatedHealth: This is a single-item, binary measure of general health status. Although multi-item scales are often preferred in research, single-item self-rated health is a widely used and validated predictor of morbidity and mortality in epidemiological studies [

26]. Its use is justified, particularly in a large-scale survey not primarily focused on health. The literature links remote work with mixed outcomes for physical health, including musculoskeletal issues due to poor ergonomics [

26] and changes in physical activity levels [

27]. This variable provides a holistic, albeit coarse, measure of the combined effect of these factors.

To further strengthen the argument for the validity of the measures used, it is recommended to create a table that visually demonstrates the content validity of the adapted scales by comparing them with concepts from the relevant literature (

Table 1). Such an approach proactively addresses potential critiques from reviewers regarding measurement quality.

The creation of such a table not only defends the methodological approach but also demonstrates a thorough command of literature, transforming a potential weakness (the use of proxy variables) into evidence of a thoughtful and theoretically grounded research design.

1.3. Deepening of Theoretical Foundations

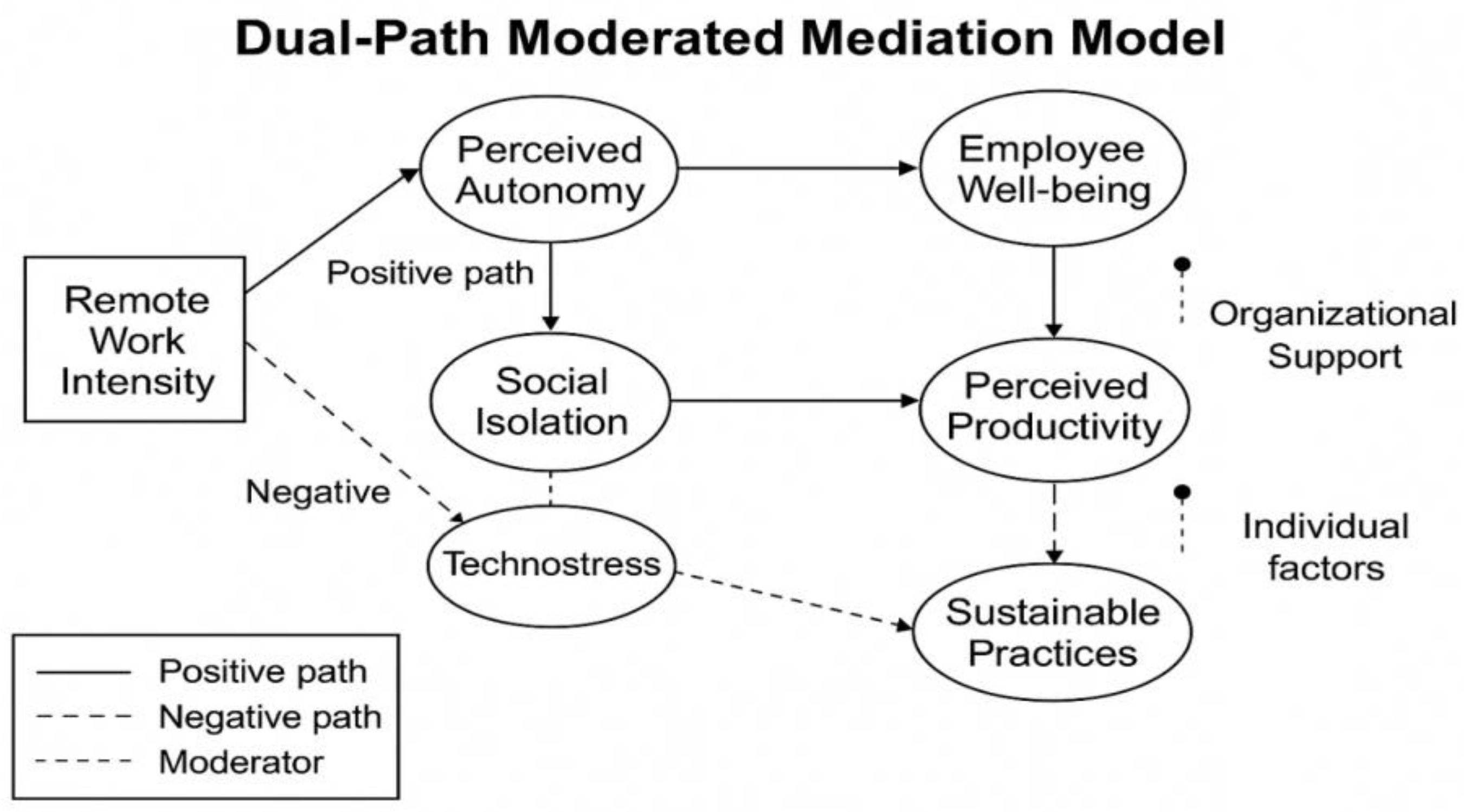

This research is grounded in three foundational theoretical frameworks: the

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) [

28], the

Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model [

29], and

Social Exchange Theory (SET) [

30]. These frameworks provide insights into how remote work can both support and hinder the fulfillment of basic psychological needs, depending on the context, age, and level of organizational support.

Importantly, we use these theories not just to frame the general impact of remote work, but to specifically explain and predict the heterogeneity of effects across different demographic groups.Previous studies suggest that remote work has positive outcomes for productivity and job satisfaction [

31]. Still, they also highlight increased risks of stress, digital overload, and compromised mental health, particularly among younger employees [

32]. However, most available research either focuses on isolated outcomes or employs qualitative methods. Quantitative research that integrates multiple dimensions and analyzes them across demographic differences remains limited, especially in developing countries [

33]. Based on these insights, this research aims to contribute to a deeper understanding of how remote work can be strategically leveraged not only to enhance organizational efficiency but also to promote employee well-being and advance sustainable development goals, in line with the 2030 Agenda [

34].

It is crucial to recognize that these theories are not static frameworks; instead, they are actively evolving and adapting to explain the new phenomena of the digital work environment.

1.3.1. The Job Demands-Resources (JD-R) Model

The fundamental premise of the JD-R model is that every job possesses specific risk factors, categorized into two main components: job demands and job resources. Job demands (e.g., pressure, task complexity) consume energy and can lead to exhaustion and health problems. Job resources (e.g., autonomy, support) help in coping with demands and foster personal growth and motivation [

35]. In the context of remote work, this model has been explicitly extended to encompass the following digital demands and resources.

Digital Job Demands: These demands transcend general work pressure to include specific techno stressors. Examples include techno-overload (the feeling of having to work faster and longer due to technology), techno-invasion (the blurring of boundaries between work and private life due to constant connectivity), techno-complexity (stress arising from the complexity of new technologies), and hyper connectivity [

36]. Research indicates that job burnout is a key mediator linking these digital demands to adverse outcomes for employee well-being [

37].

Digital Job Resources: Similarly, resources extend beyond general flexibility. Specific digital resources include technology-enabled autonomy (e.g., flexibility in choosing the time and place of work), collaboration via digital tools, and increased efficiency through technology [

38]. Organizational support, which encompasses both technical and emotional assistance, is a crucial resource that serves as a buffer against the adverse effects of digital demands [

39].

This framework, therefore, provides a strong basis for our hypotheses that remote work can simultaneously reduce certain demands (e.g., commuting) while introducing new ones (e.g., technostress), a balance that may be experienced differently across age groups.

1.3.2. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

SDT postulates that three innate psychological needs are essential for optimal human functioning, motivation, and well-being: the need for

autonomy,

competence, and

relatedness [

40]. The remote work context creates a unique arena where the satisfaction of these needs is simultaneously fostered and threatened.

Autonomy: The need to feel like the originator of one’s own actions. Remote work inherently increases autonomy by granting employees greater control over their schedule and work environment. However, this autonomy can be drastically undermined by practices of digital surveillance and micromanagement, which employees perceive as a signal of distrust [

41].

Competence: The need to feel effective and capable in mastering challenges. This need can be satisfied through access to online training and information enabled by technology. Conversely, it is directly threatened by technostress, information overload, and technical malfunctions that impede task completion and create a sense of powerlessness [

42].

Relatedness: The need to feel a sense of belonging and meaningful relationships with others. This is the need most jeopardized in the context of remote work. A reduction in face-to-face contact and the loss of spontaneous, informal interactions lead to feelings of social and professional isolation, which has been proven to be detrimental to well-being and job performance [

43]. This represents a critical point of failure for many remote work models.

Grounded in Self-Determination Theory, remote work can increase autonomy and competence while simultaneously threatening relatedness; this configuration of basic need support and thwarting provides the theoretical basis for our hypotheses regarding productivity, health, and stress [

41].

1.3.3. Social Exchange Theory (SET)

SET views interpersonal relationships within an organization as a series of reciprocal exchanges. When employees perceive that the organization invests in them and treats them fairly, they feel an obligation to reciprocate with greater commitment, engagement, and discretionary effort [

44]. In the context of remote work, where direct supervision is reduced, this theory is crucial for understanding the mechanisms of trust and proactive behavior.

The Currency of Exchange: In remote work, the “currency” of exchange is altered. The organization offers resources such as flexibility, autonomy, and trust (e.g., by avoiding invasive surveillance). In return, employees reciprocate with intrinsic motivation, higher engagement, and discretionary behaviors that go beyond the formal job description, such as assisting colleagues or taking initiative [

44].

The Breakdown of Exchange: If employees perceive a lack of support (e.g., inadequate equipment, unfair performance evaluations, a sense of distrust), the social exchange is disrupted. This leads to reduced engagement, cynicism, and a decline in performance [

45]. This mechanism is directly linked to the “manager-employee perception gap,” wherein managers often overestimate the level of support they provide, while employees perceive it as insufficient [

7].

This perspective enables us to move beyond a simple cause-and-effect view by examining how organizational support systems—such as formal procedures, evaluation practices, self-management tools, blended training, supportive leadership, and a remote work culture—shape outcomes in contexts where face-to-face supervision is reduced [

46].

The theoretical contribution of this paper, therefore, lies not only in the application of these theories but in participating in their evolution. The study can test how the newly conceptualized digital demands and resources (JD-R), the unique dynamics of need satisfaction (SDT), and the new forms of social exchange (SET) interact in predicting the dual outcomes of employee well-being and sustainability.

1.4. Research Gap, Objectives, and Hypotheses

The existing literature on remote work is characterized by two key limitations that this study aims to address. First, a pronounced lack of quantitative studies that simultaneously model the complex interplay between health, productivity, and sustainability outcomes. The existing definition of the research gap—that health and environmental effects are studied separately and that holistic studies in the IT sector are lacking—provides a sound but broad initial framework. This gap can be defined with considerably more precision and conviction by leveraging insights from the available literature.

First, it is necessary to shift the focus from the assertion that these outcomes are studied “separately” to the proposition that they are often “in conflict.” This is not merely an issue of lacking integration but of the existence of inherent tensions. For instance, the primary benefit for sustainability (reduced commuting) is simultaneously a direct benefit for health (less stress, more time for exercise). However, the “rebound effects” that complicate the sustainability picture (e.g., higher household energy consumption) are linked to adverse health outcomes (more sedentary behavior, poorer ergonomics). This creates a direct conflict between objectives: what is beneficial for reducing one’s carbon footprint (staying at home) can be detrimental to physical health if not accompanied by appropriate interventions.

Second, the research gap can be quantified. Literature provides measurable data on individual relationships. For example, it is known that full-time remote work can reduce an individual’s carbon footprint by 54% [

21]. Meta-analyses show that remote work has minor but beneficial effects on job satisfaction and performance [

24], while a meta-analysis on physical activity indicates a significant reduction in light physical activity [

27]. The specific research gap lies in the absence of studies that simultaneously model these quantified effects. For example, does the reduction in physical activity mediate the relationship between the intensity of remote work and adverse health outcomes? Is there a correlation between the decrease in the carbon footprint (a structural outcome) and the self-reported pro-environmental behavior of employees (a discretionary outcome)?

Third, there is under-researched causal direction: well-being as a precondition for sustainability. The literature suggests that employees who feel the organization cares for their well-being are more likely to engage in positive discretionary behaviors [

47]. This could plausibly be extended to pro-environmental behavior. Creating a “green work climate” fosters employees’ environmental commitment, which in turn drives innovative green behavior [

48].

The research gap can therefore be framed as testing the hypothesis that employee well-being is a necessary precondition for fostering a culture of discretionary sustainability within the context of remote work in the IT sector.

The primary objective of this research is to comprehensively evaluate the impact of remote work intensity (Remote_Intensity) on key outcomes encompassing employee well-being (perceived stress—Stress_Score, and self-rated general health—SelfRatedHealth), work productivity (Productivity_Score), and the adoption of sustainable practices (Sustainability_Score), based on the analysis of a large sample of IT employees (n > 1000). A unique contribution of this paper is the granular analysis of these relationships across key demographic variables, specifically gender and age groups, to reveal the nuanced and often contradictory effects that are obscured in aggregate analyses.

In addition to identifying direct effects, the study also aims to:

Examine the role of perceived stress as a mediator in the relationship between the intensity of remote work and the outcomes.

Analyze demographic heterogeneity, particularly the influence of gender and age groups, on these relationships to identify specific dynamics of remote work effects.

Contribute to the theoretical frameworks (JD-R, SDT, SET) by providing empirical evidence of their applicability and extension within the context of the digital work environment.

Formulate practical recommendations for IT managers and policymakers aimed at optimizing remote work models to improve employee health and promote sustainable lifestyles, acknowledging the complex interactions and potential trade-offs.

Based on the theoretical frameworks (the JD-R model, the bio psychosocial approach), we formulate the following hypotheses:

H1a. The intensity of remote work is negatively associated with perceived stress.

H1b. The intensity of remote work is positively associated with self-rated health.

H1c. The intensity of remote work is a positive predictor of self-assessed productivity.

H1d. The intensity of remote work is a positive predictor of the adoption of sustainable work practices.

H2. Perceived stress (Stress_Score) mediates the effect of remote work intensity on each of the dependent outcomes (SelfRatedHealth, Productivity_Score, Sustainability_Score).

These hypotheses form the basis for empirically testing the stated objectives, allowing for a detailed analysis and interpretation of the impact of remote work on employee well-being and sustainable lifestyles in the IT sector.