1. Introduction

The global textile industry has a significant environmental impact, contributing to pollution, waste, and greenhouse gas emissions [

1]. The fast fashion model, characterized by rapid production cycles and low-cost garments, worsens these issues by encouraging consumers to buy more clothing and use it for shorter periods, leading to overconsumption and waste. Estimates suggest that the fashion industry generates over 90 million tonnes of waste and consumes around 79 trillion liters of water annually [

2]. According to [

3], a truckload of textiles is incinerated or sent to landfills every second. This unsustainable cycle highlights the urgent need to transition towards a circular economy, where materials are reused, recycled, and repurposed to reduce environmental impact.

In Chile, the situation is equally critical. The Atacama Desert has become an informal dump for discarded clothing [

4], forming massive piles of textile waste. In 2021, Chile was the fourth-largest importer of second-hand and unsold garments worldwide, and the largest in Latin America. Of the roughly 156,000 tonnes imported that year, about 60% ended up in landfills [

5]. Despite these figures, the country lacks a coordinated institutional framework to effectively manage textile waste and promote circular practices.

The phenomenon of waste colonialism [

6], where wealthier countries export waste to less affluent nations, worsens this challenge. Much of the imported second-hand clothing cannot be resold, creating local environmental problems. Besides water and soil contamination, the long-distance transport of these garments further increases their carbon footprint.

This problem is compounded by a general lack of public awareness among Chileans about the environmental impact of clothing consumption. This limited understanding can lead to indifference and unsustainable choices. To address this, our study aims to answer the question: What key barriers and opportunities do the public and experts identify for advancing textile revalorization in Chile? Our objective is to design a management framework that supports textile circularity, informed by both public perceptions and expert insights. Although the framework developed here was not externally validated, it represents an exploratory step that provides a foundation for future refinement and testing.

This paper is organized into six main sections.

Section 2 presents a brief literature review, providing both the theoretical and empirical context for the study.

Section 3 describes the methodology used in this study, detailing the data collection instruments, sampling methods, and procedures for conducting interviews and surveys.

Section 4 offers an in-depth analysis of the results, synthesizing the data from both the public surveys and expert interviews to identify key themes and insights.

Section 5 discusses the results, comparing them with existing literature, and

Section 6 proposes an integrated management model for textile revalorization based on the findings. Finally,

Section 7 concludes the paper by summarizing the main findings, highlighting the contributions of the study, and suggesting directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The textile industry has had a significant environmental impact, contributing heavily to pollution, resource depletion, and greenhouse gas emissions. This impact covers the entire lifecycle of textile products, from raw material extraction and processing to manufacturing, transport, and disposal. Studies suggest the sector is responsible for about 20% of global industrial water pollution and roughly 10% of carbon emissions [

2]. Textile production also consumes large amounts of water, chemicals, and energy, generating substantial waste [

1].

Recycling and reuse are critical strategies to reduce textile waste and its environmental effects [

7]. Effective recycling helps conserve resources and lower pollution. Moving towards a circular economy means designing products and systems to keep materials in use for longer [

2,

8]. This approach is especially relevant for textiles, which traditionally follow a linear take-make-dispose model. In contrast, circular practices aim to reduce waste by encouraging reuse, recycling, and upcycling [

3]. Recent studies also highlight the role of repairing, as it keeps garments in use longer, avoiding impacts tied to transporting items to new users [

9]. Circularity further involves eco-design—designing products for easier recycling—and Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR), where producers remain responsible for their products’ full lifecycle [

10]. Some global brands, like H&M, Inditex, Gap, Candiani Denim, and Gucci, have adopted circular initiatives, from using recycled materials to collection programs [

11,

12]. Yet, these efforts still fall short of the full potential of circularity [

11].

Revalorization models have gained attention as key strategies for keeping textiles in the loop. These include recovering materials, upcycling, or turning waste into alternative resources, thereby reducing landfill waste. For example, ref. [

13] discuss using textile waste for energy, building materials, and chemical production. Ref. [

14] show cotton waste can be turned into briquettes with heating values of 16.8 MJ/kg, cutting fuel costs by up to 80% compared to conventional sources. Pre-consumer textile waste often has higher revalorization potential, though processing mixed materials and chemical impacts remain challenges [

13]. Others, like [

15], argue post-consumer waste should also be seen as valuable, and highlight the need for better education and separate collection systems. Ref. [

16] caution that energy recovery might be only a short-term benefit as synthetic content rises and cleaner energy sources spread. Ref. [

7] review recycling techniques, noting their importance despite challenges in collection, sorting, and scaling technologies [

15].

Public awareness and participation are crucial for successful textile recycling. The lack of consumer awareness has been identified as a significant barrier to circular economy transition, highlighting the need to raise awareness among the public about sustainability and recycling [

17]. Ref. [

18] stress the value of public consultation and education to shape attitudes. Similarly, ref. [

19] show community-based strategies, like social norms and public commitments, can boost recycling. Ref. [

20] developed a framework linking environmental values and situational factors to recycling behavior, finding that awareness of local programs and convenience—like curbside pickup—are decisive. They also highlight the importance of fostering personal responsibility.

Education is another key factor. Ref. [

21] find that higher education links to more willingness to recycle and pay for programs. Informing people about the environmental impact of waste can shift behaviors [

21,

22,

23]. For example, ref. [

24] show education sessions increased donations of used clothes, making throwing them away the least chosen option. Ref. [

25] highlight that teaching younger people fosters pro-environment habits.

Community engagement, through campaigns, workshops, and local leaders, also helps [

26,

27]. Ref. [

28] note people need better guidance on sorting clothes to support upcycling, and that charities play an important role. Yet, one-size-fits-all strategies rarely work; tailored local solutions work better [

29]. Digital tools and social media can also spread awareness and build communities [

30], though there is a risk that online support does not always become real action [

31].

Recycling in textiles is widely studied [

32], making it central to reducing environmental impacts. Ref. [

28] find that factors like upcycling, product life extension, and sustainable design help, especially among younger consumers. Ref. [

33] recommend transition plans that cover process changes, collaboration, and awareness. Successful initiatives need local adaptation. While progress is documented in Europe, there is little research for Latin America, especially Chile. This study addresses that gap by combining expert and public views to help build a more effective revalorization model for textile waste in Chile.

4. Analysis and Results Interpretation

4.1. Interview Data

The expert interviews offered valuable insights into the textile recycling landscape in Chile, reflecting perspectives from various sectors, including recycling groups, industry representatives, technical managers, legal experts, unions, and recycling companies. Experts highlighted the beneficiaries of textile valorization systems, noting that key stakeholders such as local industries, workers in recycling processes, and the environment could benefit significantly. They also emphasized the potential for job creation and the inclusion of grassroots recyclers as important beneficiaries, suggesting that an effective valorization system could deliver both economic and social advantages.

Experts agreed on the critical importance of textile circularity and recycling in Chile, citing significant environmental benefits and the urgent need to address the large volumes of textile waste. A key issue raised was the need for clear technical definitions and the inclusion of textiles in the EPR law, which could help tackle the challenges associated with recycling mixed-material textiles.

Education was identified as a key factor in promoting textile circularity. Experts agreed that building a recycling culture requires wide-ranging educational efforts, extending beyond consumers to include producers, municipal staff, and schools. Practical revalorization workshops were suggested as a way to offer hands-on learning and reinforce the importance of recycling.

The retail industry was also seen as playing a significant role in supporting recycling initiatives. Experts suggested that retailers could make a real difference by adopting practices such as eco-design and offering recycling incentives to consumers. This involvement could drive changes across the industry and encourage more sustainable consumer behaviors.

Government action was viewed as essential to create a supportive environment for textile recycling. Experts recommended the introduction of regulatory frameworks, fiscal incentives, and backing for local recycling projects. These measures could help build a strong recycling infrastructure and promote sustainable practices across the sector.

Finally, experts had different views on the commercialization of used clothing. Some saw second-hand clothing as an important part of revalorization efforts, while others raised concerns about the uncontrolled influx of used clothes from developed countries. Suggestions included restricting and regulating the import of second-hand clothing and improving local recycling infrastructure to better manage and make use of these textiles.

In summary, the interviews showed a shared view on the crucial role of education in promoting textile recycling, with both public respondents and experts stressing the need for widespread educational initiatives. The importance of involving multiple stakeholders, including industry, government, and local communities, was also highlighted as key to creating a sustainable textile recycling system. These findings are summarized in

Table 2, which outlines the main beneficiaries, key actors, and proposed initiatives for improving textile recycling in Chile.

4.2. Survey Data

The survey results provide an overview of public awareness and attitudes toward textile recycling. Most respondents (72%) reported having moderate knowledge (a rating of 3 or above on a 5-point scale) about the environmental impact of textile waste. However, a significant portion (28%) indicated little to no understanding of this issue. Almost 60% of this portion were males.

Interestingly, 70% of participants admitted they did not know where their discarded clothing ended up. Among these, 45% expressed a desire to know, while only 1% were indifferent. This indicates a substantial gap in public knowledge about the lifecycle of their textiles, coupled with a latent interest in learning more.

When asked about the primary reasons for the lack of textile recycling, 84% pointed to insufficient education on the topic. Close behind, 82% identified the lack of responsibility among textile importers. This suggests that both consumer and industry-level education and responsibility are perceived as critical barriers.

The importance of integrating textile recycling into society was overwhelmingly affirmed, with 94% of respondents supporting this idea. Most cited environmental concerns as the primary reason.

Responsibility for textile recycling was seen as a shared burden, with 49% of respondents believing it should lie with importers and manufacturers. This was followed by 26% who felt the end-consumer should be responsible, and 19% pointing to the government and municipalities.

Education emerged as the leading solution to encourage textile recycling, chosen by 90% of respondents. This was followed by economic incentives such as discounts (10%), suggesting that while education is paramount, financial motivators also play a significant role.

Figure 1 highlights the key factors hindering clothing recycling, revealing both behavioral and systemic challenges. The lack of habit for recycling and limited education on textile pollution emerged as the most significant barriers, indicating a strong need for initiatives to shift societal behaviors and raise awareness. Additionally, structural issues, such as the absence of legislation mandating recycling and insufficient infrastructure, further complicate efforts to increase participation. Interestingly, unawareness of what to do with old clothes and a general lack of information about recycling processes suggest a communication gap that could be addressed through targeted campaigns. Together, these findings underscore the need for a comprehensive approach that combines education, policy development, and infrastructure improvements to promote textile recycling.

4.3. Integrated Interview-Survey Analysis

The study involved two groups to provide different perspectives: general public respondents and experts. Despite their different viewpoints, common themes emerged that highlight the potential for a unified approach to improving textile recycling practices. For clarity and easy comparison,

Table 3 summarizes the key themes that emerged from both the public survey and expert interviews, highlighting areas of convergence and divergence in perspectives.

Both groups emphasized the critical role of education in promoting textile recycling. Survey respondents pointed out a general lack of awareness about the environmental impact of textile waste and the recycling process. Many were unsure about what happens to discarded clothing, which highlights the need for better information sharing. Experts also stressed the importance of education in fostering a recycling culture, suggesting that educational efforts should target consumers, producers, municipal staff, and schools. This alignment suggests that improving public knowledge is a key step towards increasing participation in textile recycling initiatives. Education has long been seen as a tool to raise environmental awareness about textiles, much like it has for other materials such as paper, plastic, and glass [

46]. More recently, it has been proposed as an essential action, and its positive effects on awareness have been demonstrated [

23]. This thematic convergence between experts and the public is also reflected in

Table 3.

Responsibility for textile recycling was a key area of agreement among both survey respondents and experts. Survey participants felt that responsibility should be shared among several stakeholders, including the government, municipalities, retailers, and consumers. Experts supported this view, stressing that effective recycling systems require coordinated efforts from all these groups. They emphasized the importance of government intervention through regulatory frameworks and fiscal incentives, as well as the crucial role of retailers in promoting sustainable practices.

In line with existing literature, the primary responsibility for effective textile recycling lies with multiple key stakeholders. Manufacturers and retailers must adopt sustainable practices such as eco-design and take-back programs [

47,

48]; consumers need to participate in proper disposal and recycling [

2]; and governments should create supportive regulations and incentives [

49]. Recycling companies and waste management services must innovate to process textiles efficiently, thus closing the loop in the circular economy [

7].

Barriers to recycling identified by survey respondents included a lack of convenience, insufficient facilities, and the absence of economic incentives. Respondents highlighted the need for more accessible recycling options and stronger incentives to encourage participation. Experts, on the other hand, focused on structural and systemic challenges, such as the need for better technical definitions and the inclusion of textiles in the EPR law. They also pointed out the difficulties in recycling mixed-material textiles. The convergence of these views suggests that overcoming both practical and systemic barriers is crucial for improving textile recycling efforts.

The survey responses showed that the public is willing to participate in textile recycling if they have access to the right information and facilities. This supports the views of experts, who emphasized the need for a supportive infrastructure, including workshops, local recycling projects, and incentives for eco-design and recycling practices. Experts also highlighted the importance of involving grassroots recyclers in the system, as this could bring both economic and social benefits, while strengthening the recycling network.

In conclusion, although the general public and experts approached the issue from different perspectives, their insights together underline the importance of education, shared responsibility, and systemic support in promoting textile recycling. By addressing the public’s informational needs and the structural challenges identified by experts, a comprehensive and effective textile recycling system can be developed. This integrated approach has the potential to create a more sustainable textile industry in Chile, benefiting both the environment and the local economy.

5. Discussion

The results of our study provide valuable insights into designing an effective textile revalorization system, highlighting the importance of education, shared responsibility, and systemic support. The thematic comparison presented in

Table 3 illustrates how these priorities, particularly education, responsibility distribution, and system-level coordination, are perceived by both experts and the general public. These findings align with and expand on existing literature on textile circularity and recycling.

Our findings confirm that education is crucial for raising public awareness and encouraging participation in textile recycling. A large proportion of survey respondents were unaware of the environmental impact of textile waste, which supports the observations of [

24], who showed that educational interventions can significantly change consumer behavior towards more sustainable practices. Similarly, experts stressed the need for targeted educational efforts across different demographic groups, in line with studies suggesting that tailored education can help bridge the gap between awareness and action [

23]. As recommended by different studies (e.g., [

24,

25,

28]), educational programs should be directed at consumers, producers, municipal staff, and students. However, diverging views on the roles of government and industry may pose implementation barriers, as the public often externalizes responsibility to institutions, while experts emphasize intersectoral coordination. Recognizing and addressing this misalignment through policy design and communication strategies may be key to enabling effective collaboration.

The shared responsibility for textile recycling identified in this study supports findings by [

33,

47,

48], who advocate for collaborative approaches involving manufacturers, retailers, consumers, and policymakers. Survey respondents recognized importers and manufacturers as key stakeholders, while experts emphasized the role of government intervention and fiscal incentives. This aligns with the framework proposed by [

49], which stresses the need for regulatory support and EPR to promote sustainable practices.

Our study reveals the important yet often ignored role of grassroots recyclers in textile waste management systems. Informal recyclers play a fundamental role in municipal waste recycling. Their integration into formal systems through cooperatives and microenterprises can significantly improve the collection and recycling efficiency. However, without proper recognition in public policies and regulations, their potential contribution remains limited. This aligns with our experts’ views on the need for inclusive approaches to textile revalorization in Chile. Ref. [

50] further emphasize that enforced assimilation of informal recyclers is prone to fail, while successful cooperation depends on effective consensus between formal domains and informal recycler groups. Their conceptual framework shows how informal recyclers contribute directly to waste hierarchy principles (reduce, reuse, repair, refurbish, remanufacture, and recycling) through various business models such as micro-enterprises and community-based organizations.

The role of retailers, particularly through eco-design and take-back programs, also emerged as a crucial factor. Experts in this study suggested that incentivizing consumers through retailer-led initiatives could drive industry-wide change. This finding matches research by [

7], which highlights the importance of closing the loop in the circular economy through innovations in product lifecycle management.

Barriers such as insufficient facilities, lack of convenience, and mixed-material textiles remain significant challenges to textile recycling, as highlighted by both survey respondents and expert interviews in this study. Respondents raised concerns about limited recycling options, which experts echoed, calling for clearer technical definitions and the inclusion of textiles under Chile’s EPR law. This aligns with [

51] that advocate for an ample network of collection points to facilitate the community textile recycling, and [

16], who emphasized the need for tailored solutions to overcome logistical and technical issues.

While this study focuses on Chile, our findings are consistent with broader patterns observed across Latin America. In Brazil, one of the region’s largest textile producers and consumers, recent reports estimate that only about 60,000 tonnes of textile waste are recycled annually, a modest fraction of the millions of tonnes discarded [

52]. This is despite pioneering initiatives such as the “Textile Reuse Bank” and pilot programs for reuse and circular design [

53]. Barriers such as weak reverse logistics and technological constraints still persist [

54]. In Colombia and Mexico, studies highlight the central role of informal recyclers but also emphasizes their lack of regulatory support and persistent stigmatization, which limit their effective integration into formal waste systems [

55,

56]. These challenges are similar to those observed in Chile, where limited infrastructure and reliance on informal actors remain major barriers. However, Chile’s ongoing discussion on including textiles under the EPR law represents a distinctive step forward in aligning regulation with circular economy goals. At the same time, the scarcity of systematic data in most Latin American countries underlines the need for more regional studies, as Brazil remains the only case with relatively advanced initiatives and measurable outcomes.

Although the number of expert interviews was limited, the analysis reached thematic saturation as participants provided diverse and system-wide perspectives. This saturation gives confidence in the strength of the insights we obtained. In qualitative research, the depth of interviews and the convergence of insights are more important than sample size [

34]. While a broader panel would have been desirable, access to high-level experts in this field is limited. Still, those who participated gave consistent and well-informed contributions that aligned with public survey results and existing literature. As a result, we believe our findings provide a solid and credible picture of the opportunities and barriers for textile revalorization in Chile. The inclusion of the general public was not only complementary but essential, as it captured awareness levels and behavioral barriers that are not always visible to decision-makers. However, since the survey relied on online convenience sampling, the views collected may over-represent more digitally literate or urban respondents, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Even so, the consistency between survey findings, expert interviews, and existing literature suggests that the identified barriers and opportunities remain relevant for informing policy and system design. By integrating the perspectives of both public and expert groups, this study still provides a solid foundation for designing a textile revalorization system that is tailored to Chile’s context. The findings suggest that targeted education, stakeholder collaboration, and systemic innovations are key to overcoming the challenges of textile waste. As highlighted in [

2], achieving circularity requires technological advancements alongside shifts in consumer behavior and industry practices.

It is important to note that the statistical treatment applied in this study was intentionally limited to descriptive analysis, consistent with its exploratory design and focus on contextual insights. Since our objective was to capture perceptions rather than to test predefined hypotheses through inferential statistics, more advanced statistical analyses such as ANOVA or regression were not essential for addressing the research questions guiding this study.

In conclusion, our study adds to the growing body of literature by presenting an integrated approach that brings together public engagement, expert recommendations, and systemic reforms. Taken together, these findings informed the development of the proposed framework presented in the next section, where survey and expert insights are translated into specific actions for system design. By addressing the barriers identified and encouraging collaboration among stakeholders, the proposed revalorization system has the potential to significantly reduce textile waste, lessen environmental impacts, and promote sustainable development in Chile.

6. Integrated Proposed Framework for Textile Revalorization

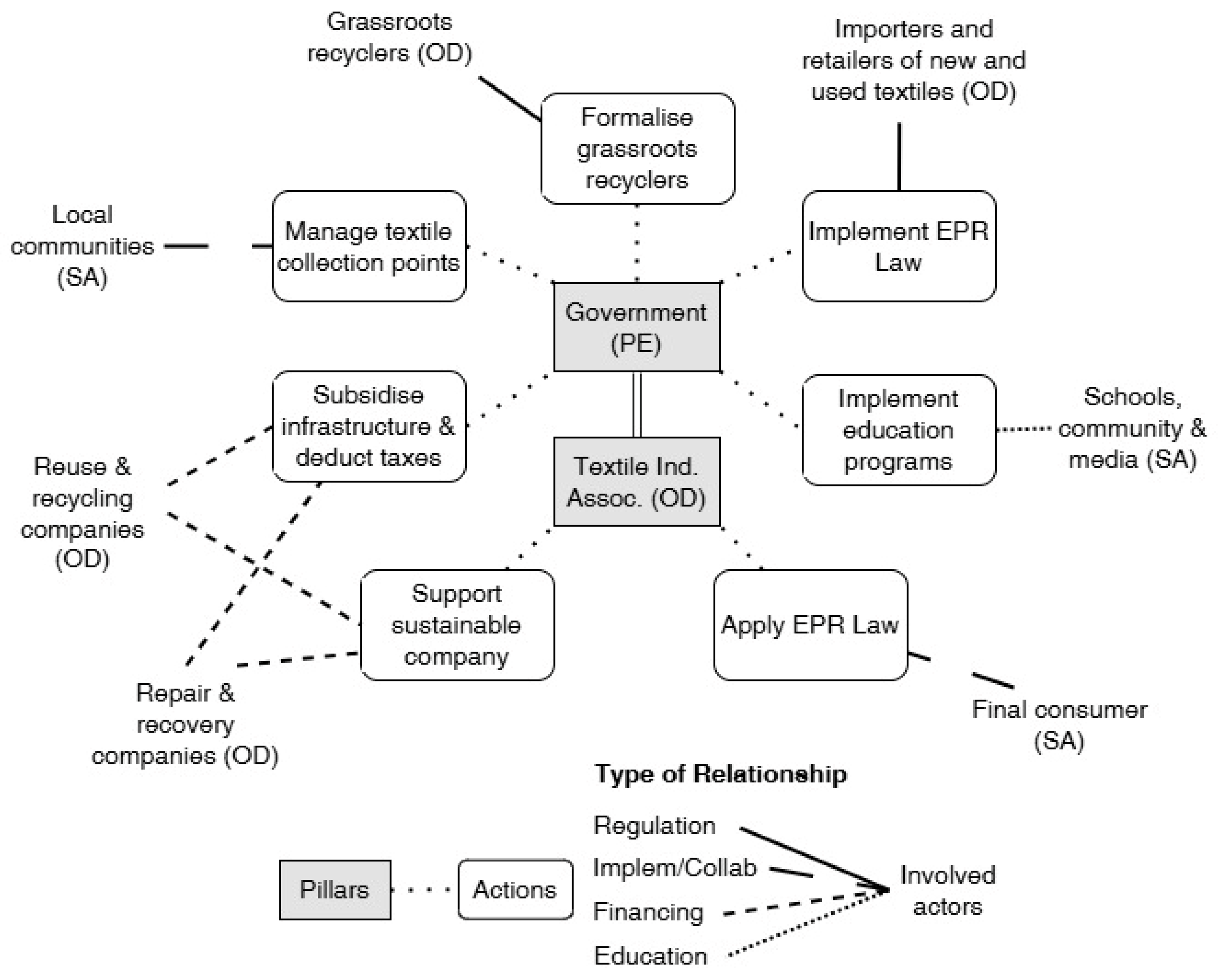

Our proposed framework for textile revalorization (

Figure 2) is built on two central pillars: Government and Textile Industry Associations. The importance of these actors emerged strongly from both expert interviews and survey results. Experts highlighted the need for stronger regulation, clearer responsibilities, and formal support for grassroots recyclers, while survey respondents pointed to the lack of infrastructure, weak coordination, and limited recycling options (

Table 3). Together, these findings show that systemic change cannot rely solely on individual behavior, but requires leadership from institutions capable of setting rules, mobilizing resources, and coordinating efforts across sectors. These pillars represent the institutional sectors with the authority and capacity to drive significant progress in textile recycling and revalorization.

Each pillar contains a set of actionable strategies, represented as rectangular nodes, which define specific responsibilities and initiatives to promote circularity in the textile sector. Surrounding the framework are various actors who contribute to or are affected by the proposed actions. These actors play different functional roles within the system—as Policy Enablers (PE), Operational Drivers (OD), or Support Actors (SA)— highlighting the need for collaboration across institutional and social sectors. To further clarify these dynamics,

Figure 2 uses different line styles to represent the type of relationship between actors and actions, distinguishing regulation, financing, implementation/collaboration, and education. The framework is thus directly linked to the empirical findings of this study, as it reflects both the priorities identified by experts and the barriers highlighted by the public survey.

The Government pillar emphasizes the role of public institutions in providing regulatory, educational, and infrastructural support to advance textile revalorization. As the main PE, the Government is responsible for creating the regulatory and educational conditions that support the transition toward textile circularity. Survey fundings underscored that structural barriers such as lack of infrastructure and clear regulation were among the most critical challenges (

Table 3). In response to this, the framework proposes actions such as integrating textiles into the EPR law, offering fiscal incentives for recycling initiatives, and restricting the import of second-hand clothing to reduce dependency on fast fashion dumping. These actions are grounded in expert insights, which highlighted the absence of clear regulation as one of the main obstacles to scaling textile recycling.

Education was also identified as a critical gap. Eighty-four percent of survey respondents identified insufficient education as the main barrier, aligning with insights from the interviews that highlighted the lack of a recycling culture. To address this, the framework calls for nationwide educational campaigns and practical workshops targeting consumers, producers, and municipal staff. These actions are designed to raise awareness, change consumer behavior and build institutional capacity at the local level. These educational efforts require the active collaboration of SA, such as schools, community organizations, and media platforms to ensure broad and sustained impact.

Another key priority identified through expert interviews was the need to formalize the work of grassroots recyclers. Currently, many operate informally without social protection or professional recognition. By strengthening their role as OD within the system, government action to formalize and professionalize recyclers not only improves their working conditions but also ensures that textile recycling becomes a stable and recognized sector. This action aligns with findings from both data sources: while the public survey emphasized the lack of visible recycling options, experts highlighted that many recycling activities are happening informally and remain invisible to formal systems.

From a feasibility perspective, implementing government-led actions may face resistance due to political costs and competing policy priorities. For example, restrictions on second-hand clothing imports could generate opposition from commercial actors that benefit from this trade. Financial barriers also exist, as public campaigns and infrastructure investments require funding. Mitigation strategies include piloting municipal-scale programs to demonstrate impact, using international cooperation funds to finance initial efforts, and promoting visible educational campaigns that build public support and pressure for political adoption.

The Textile Industry Pillar highlights the responsibility of companies and associations in leading operational change. As a primary OD, the textile industry has the capacity to innovate, finance, and comply with EPR regulations. Survey results pointed to the lack of convenient recycling options for consumers, while interviews stressed that companies rarely invest in circular initiatives without clear incentives or regulations. To address this, our framework proposes to main actions: First, supporting revalorization company funding, which includes financial mechanisms to encourage innovation in textile sorting, mixed-material recycling, and reprocessing technologies. This responds directly to the barrier of insufficient infrastructure identified in the survey, as well as to expert calls for industry-driven innovation. By funding these activities, companies can help build the necessary technical base for textile circularity. And second, compliance with the EPR law, which requires companies to take accountability for the entire lifecycle of their products. This includes implementing eco-design principles, such as the use of recyclable materials, as well as developing take-back programs to facilitate the return and recycling of used textiles (e.g., discounts or vouchers for returned used clothing). These actions connect directly with survey findings where respondents expressed the need for more accessible recycling options, as well as expert recommendations for systemic responsibility-sharing across producers and retailers.

It is important to clarify that while grassroots recyclers are essential actors in the overall recycling ecosystem, their formalization and professionalization are primarily linked to the Government Pillar. The industry’s role is centered on funding, compliance and innovation, but collaboration with recyclers is expected, particularly to expand collection and processing network. This distinction ensures a clear division of responsibilities between the two pillars, making the framework easier to interpret.

Industry-led actions also face challenges. The main difficulties are the economic viability of textile recycling, the high costs of developing new technologies, and the still limited market demand for products made from recycled fibers. Mitigation strategies may include co-financing schemes with government institutions, expanding consumer education campaigns to create demand for sustainable textiles, and forming regional clusters to share infrastructure and reduce costs.

Finally, the actors surrounding the two pillars—such as municipalities, schools, consumer groups, and grassroots recyclers—were all explicitly mentioned in either the interviews or survey responses. Their inclusion in the framework reflects the need for a whole-system approach, where responsibilities are distributed, but coordinated through the leadership of government and industry.

As the framework has not undergone a formal validation process, its current value lies in providing a structured, evidence-based proposal that integrates expert insights with public perspectives. It should be considered a preliminary model, useful for informing debate and guiding system design.

7. Conclusions

This study has explored the challenges and opportunities in advancing textile revalorization in Chile, presenting a framework to address key barriers and promote circular practices. The findings highlight the critical role of education in raising public awareness about textile recycling, addressing significant knowledge gaps identified in both survey responses and expert interviews. Shared responsibility among government, industry, and communities also emerged as a key factor in creating a sustainable recycling ecosystem.

The proposed framework represents a synthesis of the main barriers, responsibilities, and opportunities identified in the data, and provides a structured proposal to guide textile revalorization in Chile. It prioritizes actions such as improving recycling infrastructure, implementing regulatory measures—like including textiles in the Producer Responsibility Law—and fostering collaboration among stakeholders. Additionally, our findings emphasize the importance of regulating the influx of second-hand clothing from developed countries, which often overwhelms local markets and creates additional environmental burdens. Addressing this issue requires not only local policies but also a shift in global practices, with developed nations reducing the export of used clothing to developing countries and promoting sustainable consumption patterns within their own borders.

Although developed for Chile, the insights and methodology presented in this study offer valuable guidance for other countries facing similar challenges in textile waste management. By tackling behavioral, structural, and systemic barriers, the study provides actionable recommendations to advance textile circularity and reduce environmental impacts.

The framework presented here should be considered a preliminary proposal, developed from the integration of expert insights and public perspectives. While it provides a structured approach to guide textile revalorization in Chile, it has not yet been validated through a formal review process. Future research should involve participatory validation with a broader range of stakeholders, including policymakers, recyclers, and consumers, to strengthen the framework’s relevance and ensure its practical applicability. Future studies with larger and more structured datasets could also apply inferential methods such as ANOVA or regression analysis to complement these insights and further strengthen the evidence base for policy and system design. Additionally, developing training programs aimed at key stakeholders, designing the necessary legislation to support textile recycling and integrating grassroots recyclers into the system would be crucial steps. Evaluating take-back programs from retail companies and exploring further innovations in textile recycling technologies could also provide valuable insights. By continuing to explore these areas, we can enhance textile revalorization efforts and contribute to a more sustainable, circular textile economy.