Dimensions of Urban Social Sustainability: A Study Based on Polish Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

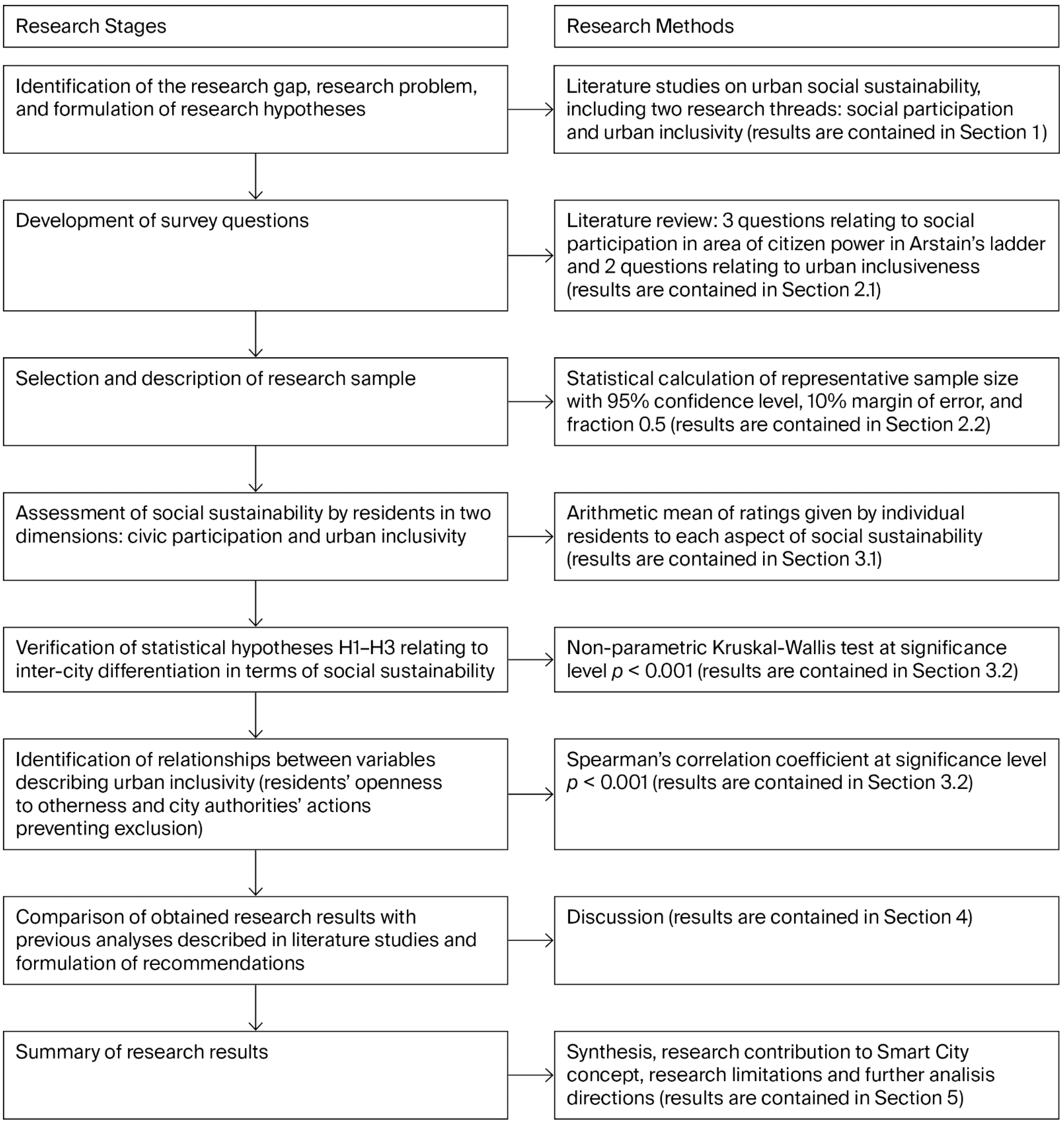

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participation as a Dimension of Urban Social Sustainability

2.2. Inclusion as a Dimension of Urban Social Sustainability

2.3. Identification of Research Gaps and Formulation of Research Objectives

- Cooperation between city authorities and residents, expressing residents’ satisfaction with the participatory policy of city authorities.

- Opportunities for residents to express their opinions on city authorities’ decisions (e.g., on public websites), illustrating the scope of civic control.

- The use of civic budgets, reflecting the scale of use of one of the main tools of social participation.

- The openness of residents to diversity/otherness (cultural, national, religious, etc.), referring to social acceptance of otherness and, at the same time, a social expression of inclusiveness.

- Support provided by city authorities to people at risk of exclusion (individuals on a low income, those with disabilities, older people, migrants, etc.), reflecting the commitment of city authorities to counteracting various forms of exclusion.

2.4. Characteristics of the Sample and Research Methods

- Cities aspiring to be smart are typically large units with significant decision-making power. In Poland, such cities are those with county rights. In the case of this research, these are all counties from 1 region—the Silesian Voivodeship.

- Inter-city comparisons were a focus of this research. For their results to be useful for individual policies of local authorities, the cities should operate under similar regional conditions. This criterion is met due to their location in close proximity within the Silesian Voivodeship.

- Previous empirical research on Smart Cities covers very large metropolises, capitals of countries, or capitals of regions. This trend was avoided in this research, especially since not only flagship cities of a given country can aspire to be smart. Therefore, this research included 19 large cities operating in the same region with aspirations to be smart, but also with everyday problems in their local communities.

- Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test (Hypotheses H1–H3) used for comparisons of more than two independent groups (significance level: 0.001).

- Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (Hypothesis H4) (significance level: 0.001).

- This research approach was used to assess the overall social sustainability of the examined cities and to verify the proposed research hypotheses.

- After describing the research results, they were compared with previous analyses within the framework of the discussion. In this part of the research, recommendations for improving urban social sustainability were also identified. In the final stage, the obtained conclusions were synthesized, research limitations were indicated, and directions for further considerations were outlined.

3. Results

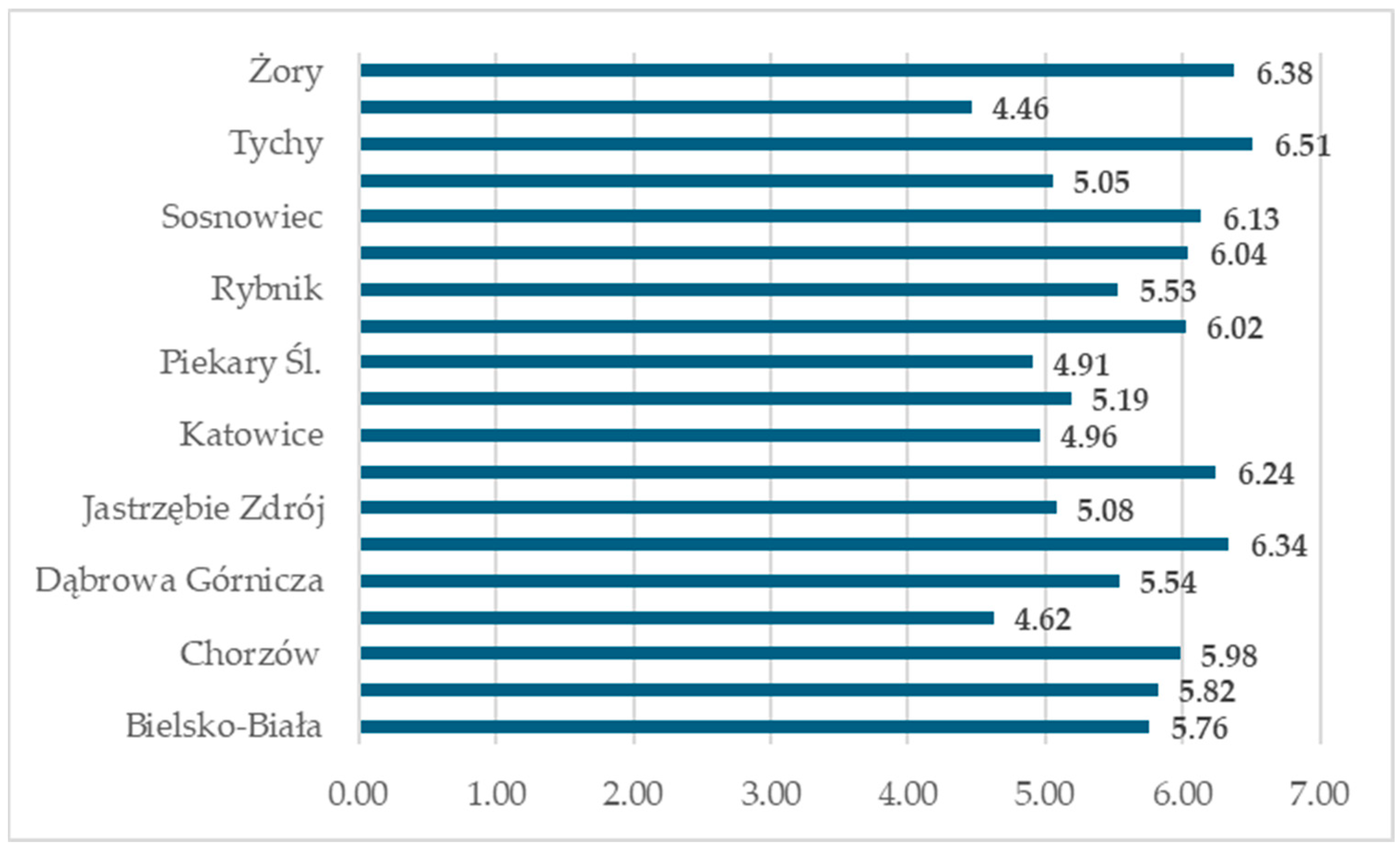

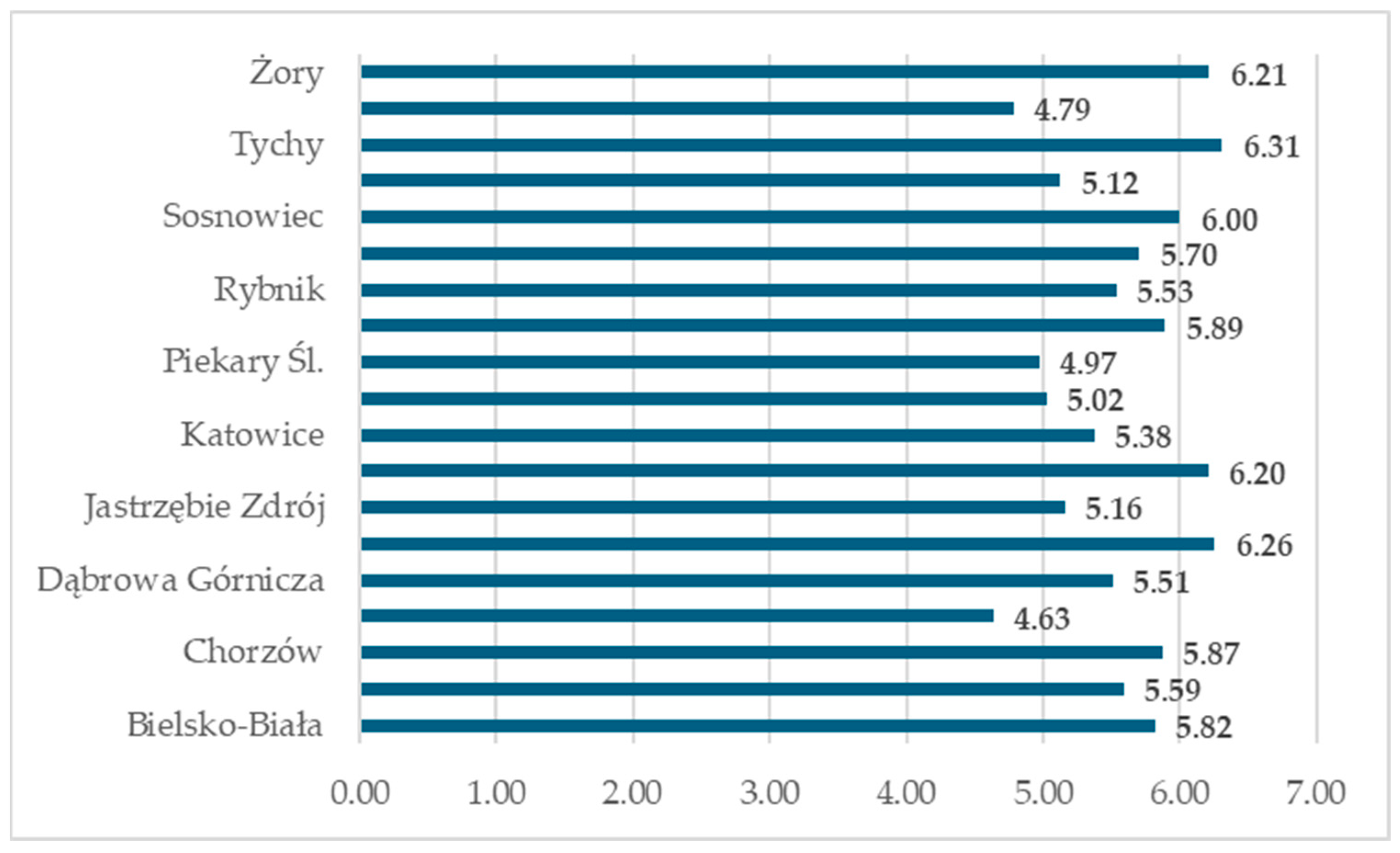

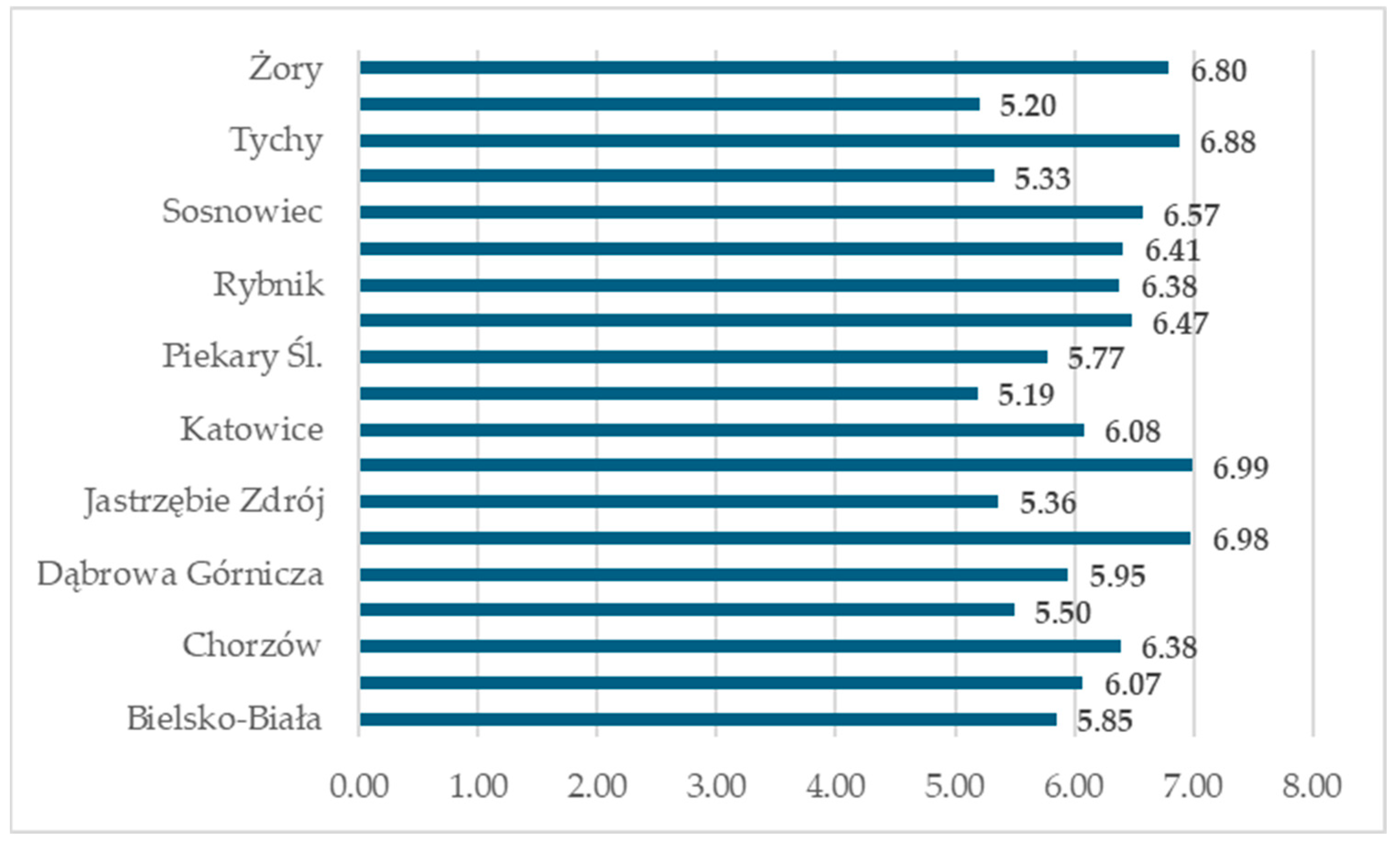

3.1. Assessment of Social Sustainability in the Cities Surveyed

3.2. Regional Differences in Social Sustainability—The Role of Local Authorities

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison of Research Results with Previous Analyses and Observations

4.2. Smart Governance Recommendations

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of the Research Results

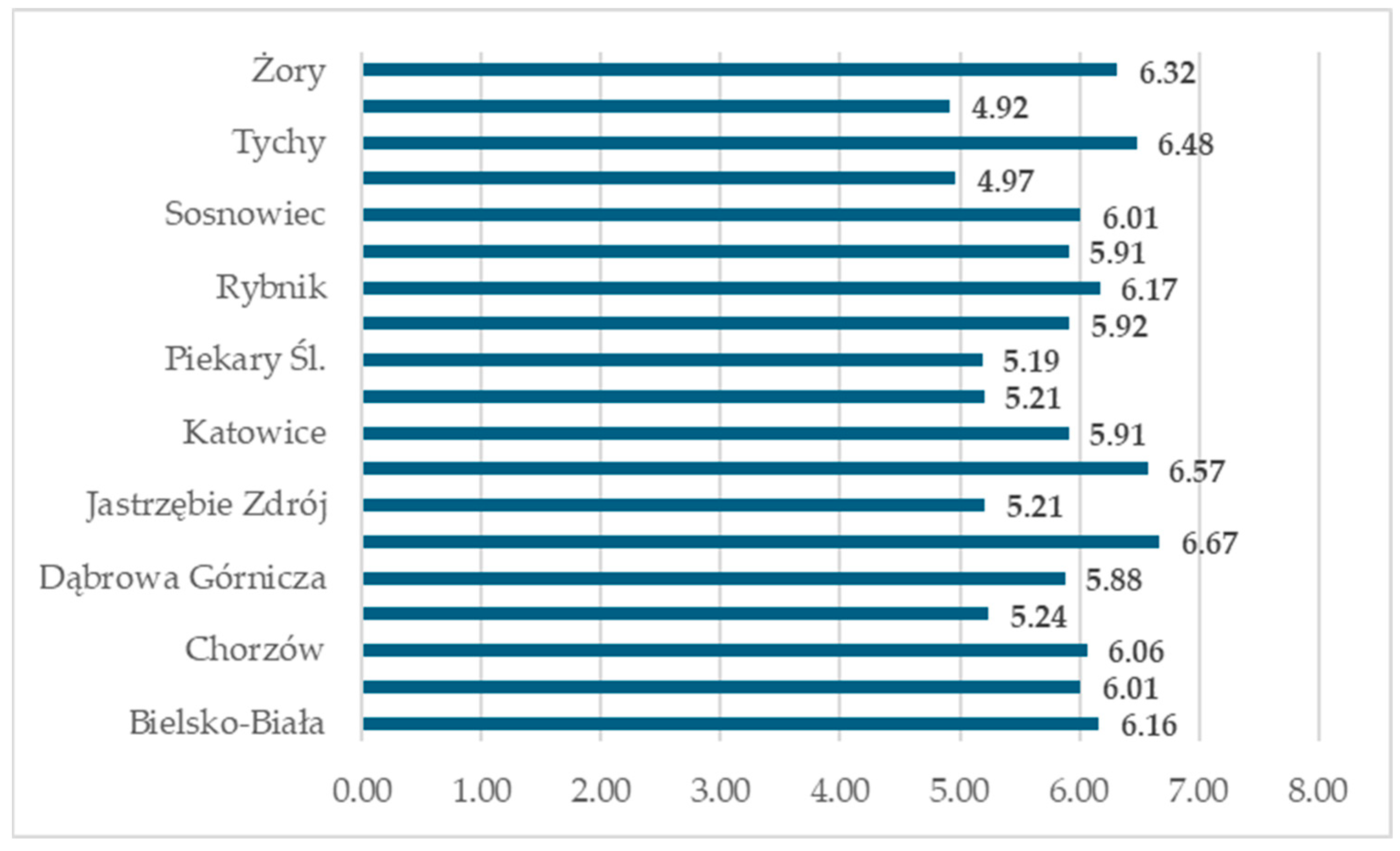

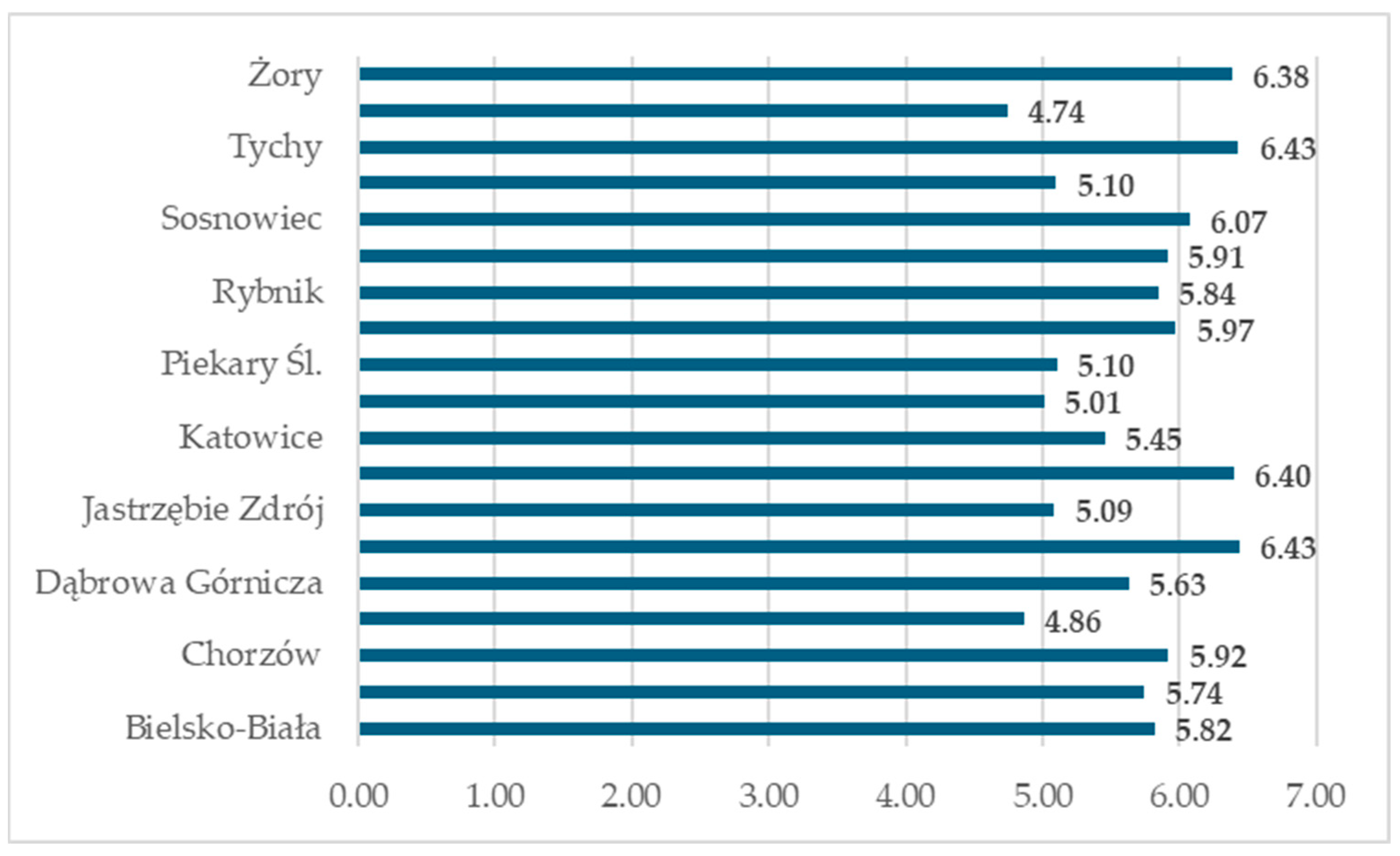

- The social sustainability of the Polish cities surveyed is generally rated between 4 and 6 (on a scale of 0 to 10) in each aspect, which indicates a rather low to average level.

- The hierarchy of assessments of individual aspects in the eyes of residents is as follows: civic budgeting (6.11), residents’ openness to diversity (5.83), cooperation between city authorities and the local community (5.61), and counteracting exclusion (5.26).

- Some cities receive high scores in each of the assessed aspects (Gliwice, Tychy, Jaworzno, and Żory), which indicates consistent and coherent actions by city authorities to promote social sustainability.

- Some cities receive very low scores in each of the assessed aspects (Zabrze, Piekary Śląskie, and Częstochowa). Their common features are a fairly low standard of living and ineffective reindustrialization after the closure of coal mining.

- Provincial cities (Katowice and the former provincial city Częstochowa) do not stand out in terms of social sustainability. This means that social sustainability does not always correspond to the size of the city and its administrative privileges.

- The cities surveyed differ from each other in all the aspects analyzed, particularly in terms of the overall assessment of cooperation between local authorities and the urban community and in terms of counteracting exclusion.

- There is a statistically significant positive correlation between residents’ openness to diversity and the actions taken by city authorities to reduce exclusion.

- Social sustainability in cities in developing economies is not highly rated by residents, but the scores obtained indicate that its dimensions are recognized and that municipal authorities are active in promoting it.

- Unfavorable living and economic conditions can have a negative impact on the social sustainability of cities.

- Social sustainability is a characteristic feature of a given city and varies greatly even at the regional level.

- Therefore, local social sustainability largely depends on the decisions and actions of the city authorities.

- A high level of openness of the local community to diversity/otherness can provide important support in cities’ efforts to achieve social sustainability.

- It closes a substantive research gap relating to the lack of bottom-up research on social sustainability (perspective and assessment of residents).

- It also closes the methodological research gap concerning the lack of extensive research on local communities (resident surveys instead of case studies, analyses of municipal source documents or literature studies).

- It describes the problems faced by cities aspiring to be sustainable and smart (in the face of the dominance of Smart City case studies from highly developed economies).

- It determines the level of residents’ satisfaction with city authorities’ social sustainability policies based on a representative sample of residents from 19 cities.

- It also determines the level of openness to diversity based on a representative sample of 1863 residents.

- It presents an assessment of measures against social exclusion from residents of 19 cities in developing economies.

- It compares residents’ assessment of openness to diversity with the assessment of measures against social exclusion carried out by city authorities.

- The observations mentioned above contribute to the diagnosis and assessment of urban social sustainability in large cities in the emerging European economy. They can be used for comparative analyses and also serve as guidance for strengthening individual areas of local community participation in city life.

5.2. Research Limitations and Directions for Further Analysis

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahvenniemi, H.; Huovila, A.; Pinto-Seppä, I.; Airaksinen, M. What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? Cities 2017, 60, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toli, A.M.; Murtagh, N. The concept of sustainability in smart city definitions. Front. Built Environ. 2020, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Lopez, L.J.; Grijalba Castro, A.I. Sustainability and Resilience in Smart City Planning: A Review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávid, L.D.; El Archi, Y. Beyond boundaries: Navigating smart economy through the lens of tourism. Oeconomia Copernic. 2024, 15, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Founoun, A.; Hayar, A.; Haqiq, A. Regulation and local initiative for the development of smart cities-sustainable penta-helix approach. Int. J. Tech. Phys. Probl. Eng. 2021, 13, 55–61. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, F.; Vairinhos, V.M.; Dameri, R.P.; Durst, S. Increasing smart city competitiveness and sustainability through managing structural capital. J. Intellect. Cap. 2017, 18, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, K.; Cooper, I. Investigating the Effects of the Quadruple Helix on Civic Society Engagement in Smart City Innovation. J. Innov. Manag. 2024, 12, 171–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, D.; Syukri, F.; Subiyanto, A.F.; Utdityasan, R.N. Smart city Nusantara development through the application of Penta Helix model (A practical study to develop smart city based on local wisdom). In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on ICT for Smart Society 2016, (ICISS), Surabaya, Indonesia, 20–21 July 2016; pp. 80–85. [Google Scholar]

- Calzada, I. Democratising Smart Cities? Penta-Helix Multistakeholder Social Innovation Framework. Smart Cities 2020, 3, 1145–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydesdorff, L.; Deakin, M. The triple-helix model of smart cities: A neo-evolutionary perspective. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgazzar, R.F.; El-Gazzar, R. Smart Cities, Sustainable Cities, or Both?—A Critical Review and Synthesis of Success and Failure Factors. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Cities and Green ICT Systems, Porto, Portugal, 22 April 2017; Volume 2, pp. 250–257. [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta, U.; Sengupta, U. Why government supported smart city initiatives fail: Examining community risk and benefit agreements as a missing link to accountability for equity-seeking groups. Front. Sustain. Cities 2022, 4, 960400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijshouwer, E.A.; Leclercq, E.M.; van Zoonen, L. Public views of the smart city: Towards the construction of a social problem. Big Data Soc. 2022, 9, 20539517211072190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateş, M.; Erinsel Önder, D. A local smart city approach in the context of smart environment and urban resilience. Int. J. Disaster Resil. Built Environ. 2023, 14, 266–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, F.; Vairinhos, V.; Durst, S.; Dameri, R.P. Intellectual Capital and Innovation for Sustainable Smart Cities: The Case of N-Tuple of Helices. In Intellectual Capital Management as a Driver of Sustainability; Matos, F., Vairinhos, V., Selig, P.M., Edvinsson, L., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, W.; Huang, G.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, S.; Feng, H. How to enhance citizens’ sense of gain in smart cities? A SWOT-AHP-TOWS approach. Soc. Indic. Res. 2023, 165, 787–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleophas, T.J.; Zwinderman, A.H. Non-parametric tests for three or more samples (Friedman and Kruskal-Wallis). In Clinical Data Analysis on a Pocket Calculator: Understanding the Scientific Methods of Statistical Reasoning and Hypothesis Testing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 193–197. [Google Scholar]

- Jóźwiak, J.; Podgórski, J. Statystyka od Podstaw; PWE: Warszawa, Poland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- De Winter, J.C.; Gosling, S.D.; Potter, J. Comparing the Pearson and Spearman correlation coefficients across distributions and sample sizes: A tutorial using simulations and empirical data. Psychol. Methods 2016, 21, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ręklewski, M. Statystyka Opisowa. Teoria i Przykłady; Państwowa Uczelnia Zawodowa we Włocławku: Włocławek, Poland, 2020; pp. 97–100. [Google Scholar]

- Garau, C.; Pavan, V.M. Evaluating urban quality: Indicators and assessment tools for smart sustainable cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasmeier, A.; Nebiolo, M. Thinking about smart cities: The travels of a policy idea that promises a great deal, but so far has delivered modest results. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, A.; Caprotti, F.; Cugurullo, F. (Eds.) Inside Smart Cities: Place, Politics and Urban Innovation; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo, P.; Kitchin, R. Being a ‘citizen’ in the smart city: Up and down the scaffold of smart citizen participation in Dublin, Ireland. GeoJournal 2019, 84, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowley, R.; Caprotti, F. Smart city as anti-planning in the UK. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 2019, 37, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, T.; Zook, M.; Wiig, A. The ‘actually existing smart city’. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2015, 8, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanolo, A. Is there anybody out there? The place and role of citizens in tomorrow’s smart cities. Futures 2016, 82, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelbert, J.; van Zoonen Hirzalla, F. Excluding citizens from the European smart city: The discourse practices of pursuing and granting smartness. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 142, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paskaleva, K.; Evans, J.; Watson, K. Co-producing smart cities: A Quadruple Helix approach to assessment. Eur. Urban Reg. Stud. 2021, 28, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghys, K.; van der Graaf, S.; Walravens, N.; Van Compernolle, M. Multi-Stakeholder Innovation in Smart City Discourse: Quadruple Helix Thinking in the Age of “Platforms”. Front. Sustain. Cities 2020, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos, D.; Fernández-Caballero, A.; Pereira, A.; Rocha, N.P. Smart City Applications to Promote Citizen Participation in City Management and Governance: A Systematic Review. Informatics 2022, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenda, A.M.; Keough, N.; Rock, M.; Miller, B. Rethinking public participation in the smart city. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe Can. 2020, 64, 344–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senior, C.; Temeljotov Salaj, A.; Johansen, A.; Lohne, J. Evaluating the Impact of Public Participation Processes on Participants in Smart City Development: A Scoping Review. Buildings 2023, 13, 1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willems, J.; Van den Bergh, J.; Viaene, S. Smart City Projects and Citizen Participation: The Case of London. In Public Sector Management in a Globalized World; Andeßner, R., Greiling, D., Vogel, R., Eds.; NPO-Management; Springer Gabler: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansera, M.; Marsh, A.; Owen, R.; Flores López, J.A.; De Alba Ulloa, J.L. Exploring Citizen Participation in Smart City Development in Mexico City: An institutional logics approach. Organ. Stud. 2022, 44, 1679–1701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelnovo, W. Co-production Makes Cities Smarter: Citizens’ Participation in Smart City Initiatives. In Co-Production in the Public Sector; Fugini, M., Bracci, E., Sicilia, M., Eds.; SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeybilovicz, E.; Cunha, M.A.; Geertman, S.; Leleux, C.; Michels, A.; Tomor, Z.; Webste, C.W.R.; Meijer, A. Citizen participation in the smart city: Findings from an international comparative study. Local Gov. Stud. 2020, 48, 23–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, A.M.; Wigley, E.; Zanetti, O.; Rose, G. Learning lessons for avoiding the inadvertent exclusion of communities from smart city projects. In Shaping Smart for Better Cities; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 221–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhu, W. Evaluating the impact mechanism of citizen participation on citizen satisfaction in a smart city. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020, 48, 2466–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubicki, P. The Civic Budget as an Element of Social Participation. Pub. Pol’y Stud. 2021, 8, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepańska, A.; Zagroba, M.; Pietrzyk, K. Participatory budgeting as a method for improving public spaces in major polish cities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2022, 162, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schugurensky, D.; Mook, L. Participatory budgeting and local development: Impacts, challenges, and prospects. Local Dev. Soc. 2024, 5, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shybalkina, I. Toward a positive theory of public participation in government: Variations in New York City’s participatory budgeting. Public Adm. 2022, 100, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarska-Olejniczak, D.; Olejniczak, J. Participatory budget of Wrocław as an element of smart city 3.0 concept. Sborník Příspěvků XIX. Mezinárodní Kolokvium O Reg. Vědách Čejkovice 2016, 15, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Węglarz, B. Participatory Budget in Poland as a Smart City 3.0 Tool Improving the Quality of Life and Safety of Residents. Юридически сборник 2022, 29, 89–98. [Google Scholar]

- Giela, M. The human element in the context of smart cities. Manag. Syst. Prod. Eng. 2023, 31, 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skouloudakis, A.; Christopoulou, E. Participatory budgeting: Combining smart cities and open data. In Proceedings of the 25th Pan-Hellenic Conference on Informatics; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karachay, V.; Chugunov, A.; Neustroeva, R. Participatory budgeting and e-Participation in smart cities: Comparative overview. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 835–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treija, S.; Stauskis, G.; Korolova, A.; Bratuškins, U. Community engagement in urban experiments: Joint effort for sustainable urban transformation. Landsc. Archit. Art 2023, 22, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monachesi, P. Shaping an alternative smart city discourse through Twitter: Amsterdam and the role of creative migrants. Cities 2020, 100, 102664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berntzen, L.; Johannessen, M. The Role of Citizen Participation in Municipal Smart City Projects: Lessons Learned from Norway. In Public Administration and Information Technology; Gil-Garcia, J., Pardo, T., Nam, T., Eds.; Smarter as the New Urban Agenda; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Dambruch, J.; Peters-Anders, J.; Sackl, A.; Strasser, A.; Fröhlich, P.; Templer, S.; Soomro, K. Developing knowledge-based citizen participation platform to support Smart City decision making: The Smarticipate case study. Information 2017, 8, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viale Pereira, G.; Cunha, M.A.; Lampoltshammer, T.J.; Parycek, P.; Testa, M.G. Increasing collaboration and participation in smart city governance: A cross-case analysis of smart city initiatives. Inf. Technol. Dev. 2017, 23, 526–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Grebski, W. Community engagement in smart city–smartphone applications aspects. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Śląskiej. Organ. I Zarządzanie 2023, 189, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolniak, R.; Stecuła, K. Artificial intelligence in smart cities—Applications, barriers, and future directions: A review. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1346–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, K.I.; Owoc, M.L. Exclusion services in smart city knowledge portal. Inform. Ekon. 2015, 2, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, K.S. Whose right to the smart city? In The Right to the Smart City; Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2019; pp. 27–41. [Google Scholar]

- Tadili, J.; Fasly, H. Citizen participation in smart cities: A survey. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Smart City Applications, Casablanca, Morocco, 2–4 October 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waisová, Š. The tragedy of smart cities in Egypt. how the Smart City is used towards political and social ordering and exclusion. Appl. Cybersecur. Internet Gov. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Loiacono, E.T.; Kordzadeh, N. Smart cities for people with disabilities: A systematic literature review and future research directions. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2023, 33, 845–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempin Reuter, T. Human rights and the city: Including marginalized communities in urban development and smart cities. J. Hum. Rights 2019, 18, 382–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolotouchkina, O.; Barroso, C.L.; Sánchez, J.L.M. Smart cities, the digital divide, and people with disabilities. Cities 2022, 123, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavurova, B.; Polishchuk, V. Decision-making support system for travel planning for people with disabilities based on fuzzy set theory. Oeconomia Copernic. 2025, 2025, 417–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makkonen, T.; Inkinen, T. Inclusive smart cities? Technology-driven urban development and disabilities. Cities 2024, 154, 105334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Wolniak, R. Exclusion in Smart Cities: Assessment and Strategy for Strengthening Resilience; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Jonek-Kowalska, I.; Wolny, M. Age Sustainability in Smart City: Seniors as Urban Stakeholders in the Light of Literature Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, T.; Samuelsson, U.; Viscovi, D. At risk of exclusion? Degrees of ICT access and literacy among senior citizens. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2017, 22, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo, A.J. Inclusive and Safe Mobility Needs of Senior Citizens: Implications for Age-Friendly Cities and Communities. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suopajärvi, T. From Tar City to Smart City: Living with the Smart City Ideology as Senior City Dweller. Ethnol. Fenn. 2018, 45, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.; Neo, X.S. Smart Cities for Aging Populations: Future Trends in Age-Friendly Public Health Policies. J. Foresight Health Gov. 2025, 2, 11–20. Available online: https://www.journalfph.com/index.php/jfph/article/view/2 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Fernanda Medina Macaya, J.; Ben Dhaou, S.; Cunha, M.A. Gendering the Smart Cities: Addressing gender inequalities in urban spaces. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Theory and Practice of Electronic Governance; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, S.; Metternicht, G.; Laffan, S.; Hawken, S. Intelligent spatial technologies for gender inclusive urban environments in today’s smart cities. Intell. Environ. 2023, 285–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, R.; Andrucki, M. Smart cities: Who cares? Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2020, 53, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, T.; Roychowdhury, P.; Rawat, P. Gender and smart city: Canvassing (in)security in Delhi. GeoJournal 2022, 87, 2307–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Singh, S. Does CEO gender impact dividends in emerging economies? Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2025, 22, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Phung, V.A.; Digdowiseiso, K.; Afni, N. Bridging the gender wage gap: The role of education in developing economies. J. Econ. Stud. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayin, M.; Ekhtiari, M. Immigrants Living in Smart Cities: A Systematic Review of Their Digital Technology Adoption and an Empirical Study on the Adoption of Smart City Applications. J. Urban Technol. 2024, 31, 49–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamad Mouazen, A.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. The role of sustainability in the relationship between migration and smart cities: A bibliometric review. Digit. Policy Regul. Gov. 2021, 23, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, H. Socio-technical challenges in the implementation of smart city. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Innovation and Intelligence for Informatics, Computing, and Technologies (3ICT), Zallaq, Bahrain, 29–30 September 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- Daher, E.; Kubicki, S.; Guerriero, A. Data-driven development in the smart city: Generative design for refugee camps in Luxembourg. Entrep. Sustain. Issues 2017, 4, 364–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monachesi, P.; Witteborn, S. Building the sustainable city through Twitter: Creative skilled migrants and innovative technology use. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 58, 101531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhang, X.; Geertman, S. Toward smart governance and social sustainability for Chinese migrant communities. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 107, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHart, J. Understanding equity and diversity in smart city infrastructures: Chicago, IL, USA. XRDS: Crossroads. ACM Mag. Stud. 2022, 28, 60–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demirel, D. The Impact of Managing Diversity on Building the Smart City A Comparison of Smart City Strategies: Cases from Europe, America, and Asia. SAGE Open 2023, 13, 21582440231184971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šulyová, D.; Vodák, J. The Impact of Cultural Aspects on Building the Smart City Approach: Managing Diversity in Europe (London), North America (New York) and Asia (Singapore). Sustainability 2020, 12, 9463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdal Oktay, S.; Oliver, S.T.; Acedo, A.; Benitez-Paez, F.; Gupta, S.; Kray, C. Openness: A Key Factor for Smart Cities. In Handbook of Smart Cities; Augusto, J.C., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenna, H. Rethinking Learning in the Smart City: Innovating Through Involvement, Inclusivity, and Interactivities with Emerging Technologies. In Smarter as the New Urban Agenda. Public Administration and Information Technology; Gil-Garcia, J., Pardo, T., Nam, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degbelo, A.; Granell, C.; Trilles, S.; Bhattacharya, D.; Casteleyn, S.; Kray, C. Opening up Smart Cities: Citizen-Centric Challenges and Opportunities from GIScience. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, I.K. Key Themes and Conceptual Frameworks for a Smart-Inclusive City: A Scoping Review. J. Plan. Lit. 2025, 08854122241312909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, N.; Hoppe, T.; van der Werf, I.; Janssen, M. A framework to analyze inclusion in smart energy city development: The case of Smart City Amsterdam. Cities 2025, 158, 105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, H.; Dikmen, I. Inclusive Smart Cities: An Exploratory Study on the London Smart City Strategy. Buildings 2024, 14, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trindade, E.P.; Hinnig, M.P.F.; da Costa, E.M.; Marques, J.S.; Bastos, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Sustainable development of smart cities: A systematic review of the literature. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Tomadon, L.; do Couto, E.V.; de Vries, W.T.; Moretto, Y. Smart city and sustainability indicators: A bibliometric literature review. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dashkevych, O.; Portnov, B.A. Criteria for Smart City Identification: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bielińska-Dusza, E.; Hamerska, M.; Żak, A. Sustainable Mobility and the Smart City: A Vision of the City of the Future: The Case Study of Cracow (Poland). Energies 2021, 14, 7936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatfield, A.T.; Reddick, C.G. Smart city implementation through shared vision of social innovation for environmental sustainability: A case study of Kitakyushu, Japan. Soc. Sci. Comput. Rev. 2016, 34, 757–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girardi, P.; Temporelli, A. Smartainability: A methodology for assessing the sustainability of the smart city. Energy Procedia 2017, 111, 810–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibri, S.E.; Krogstie, J. The emerging data–driven Smart City and its innovative applied solutions for sustainability: The cases of London and Barcelona. Energy Inform. 2020, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavada, M.; Tight, M.R.; Rogers, C.D. A smart city case study of Singapore—Is Singapore truly smart? In Smart City Emergence; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, G.W.; Vettorato, D.; Sagoe, G. Creating Smart Energy Cities for Sustainability through Project Implementation: A Case Study of Bolzano, Italy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riadh, A.D. Dubai, the sustainable, smart city. Renew. Energy Environ. Sustain. 2022, 7, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzoha, A.; Nieminen, J.; Piya, S.; Rutledge, K. Smart city for sustainable environment: A comparison of participatory strategies from Helsinki, Singapore and London. Cities 2021, 114, 103194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorwinden, A. Regulating the smart city in European municipalities: A case study of Amsterdam. Eur. Public Law 2022, 28, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyadeyi, O.A.; Oyadeyi, O.O. Towards inclusive and sustainable strategies in smart cities: A comparative analysis of Zurich, Oslo, and Copenhagen. Res. Glob. 2025, 10, 100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makushkin, S.A.; Kirillov, A.V.; Novikov, V.S.; Shaizhanov, M.K. Role of Inclusion “Smart City” Concept as a Factor in Improving the Socio-economic Performance of the Territory. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2016, 6, 152–156. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://rainbowmap.ilga-europe.org/countries/poland/ (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Drozdzewski, D.; Matusz, P. Operationalising memory and identity politics to influence public opinion of refugees: A snapshot from Poland. Political Geogr. 2021, 86, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| City | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Bielsko-Biała | attractive in terms of tourism and culture; good climate quality | low industrialization; migration of young residents to more economically attractive cities |

| Bytom | accessibility of transport and logistics routes; long mining traditions | high unemployment; ineffective reindustrialization after the closure of coal mining |

| Chorzów | sports, cultural, and entertainment attractions; accessibility and numerous transport connections | depopulation of the local community; high environmental pollution |

| Częstochowa | religious tourism; crossroads of important national transport routes | dependence of the labor market on traditional heavy industries; environmental pollution |

| Dąbrowa Górnicza | good logistics; development of the metallurgical industry | environmental degradation; dependence on traditional industries |

| Gliwice | development of the automotive and IT sectors; development of universities and modern technologies | high cost of living; increasing urbanization and its negative effects |

| Jastrzębie-Zdrój | location near the Polish border; activities of a strategic mining company (coke coal mining) | migration of young people to larger cities; dependence on traditional industry |

| Jaworzno | recreational attractions—lots of green areas; investment in renewable energy sources | environmental degradation related to the mining past; high unemployment |

| Katowice | provincial capital—business and cultural center; well-developed transport network | high cost of living; environmental pollution related to mining industry residues |

| Mysłowice | low cost of living; development of logistics and services | heavy traffic; lack of local attractions |

| Piekary Śląskie | religious tourism; many green and recreational areas | ineffective reindustrialization after the closure of coal mines; degradation of post-industrial areas |

| Ruda Śląska | favorable transport location; long mining tradition | depopulation; mining damage and environmental pollution |

| Rybnik | opportunities for cross-border cooperation; good quality of life | strong dependence on traditional industries; post-mining environmental degradation |

| Siemianowice Śląskie | good transport links; low cost of living | high unemployment; migration to more attractive cities |

| Sosnowiec | development of trade and services; well-developed transport hub | degradation of housing stock; depopulation |

| Świętochłowice | low cost of living; small size and availability of green areas | high unemployment; degradation of urban infrastructure, especially housing |

| Tychy | development of the automotive industry; attractive place to live due to its development and sports and recreational attractions | low industrial diversity; rising cost of living |

| Zabrze | good transport links; sports, mining and post-industrial traditions | ineffective reindustrialization following the closure of coal mines; deterioration of housing stock and mining damage |

| Żory | well-developed entrepreneurship; clean environment and plenty of green space | peripheral location; depopulation |

| Cities | Variables | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooperation with City Authorities | Civic Control | Participatory Budgeting | Residents’ Openness to Diversity | City Measures Against Exclusion | |

| Test Parameters | |||||

| H (18, N = 1863) = 107.1366; p = 0.0000 | H (18, N = 1863) = 75.1068 p = 0.0000 | H (18, N = 1863) = 104.7522 p = 0.0000 | H (18, N = 1863) = 95.5989 p = 0.0000 | H (18, N = 1863) = 105.6684 p = 0.0000 | |

| Mean of Ranks | |||||

| Bielsko-Biała | 959.53 | 981.33 | 875.94 | 1004.32 | 972.31 |

| Bytom | 966.89 | 929.04 | 913.46 | 962.31 | 929.20 |

| Chorzów | 984.39 | 974.99 | 973.03 | 960.35 | 925.30 |

| Częstochowa | 726.27 | 721.95 | 810.36 | 809.43 | 722.90 |

| Dąbrowa Górnicza | 929.29 | 934.43 | 899.45 | 954.99 | 945.57 |

| Gliwice | 1085.83 | 1079.56 | 1131.67 | 1141.33 | 1091.64 |

| Jastrzębie-Zdrój | 811.42 | 829.34 | 767.25 | 776.01 | 779.28 |

| Jaworzno | 1057.10 | 1062.30 | 1116.77 | 1091.98 | 1089.46 |

| Katowice | 782.06 | 882.94 | 935.88 | 936.98 | 849.18 |

| Mysłowice | 860.97 | 837.00 | 760.08 | 821.77 | 777.18 |

| Piekary Śl. | 810.77 | 818.74 | 852.88 | 779.36 | 811.58 |

| Ruda Śl. | 1005.13 | 983.19 | 995.53 | 942.83 | 982.40 |

| Rybnik | 902.05 | 904.89 | 975.35 | 996.08 | 994.71 |

| Siemianowice Śl. | 1023.75 | 957.83 | 993.22 | 944.52 | 975.67 |

| Sosnowiec | 1042.46 | 1043.40 | 1031.95 | 979.12 | 1016.01 |

| Świętochłowice | 817.86 | 827.84 | 763.78 | 737.75 | 881.85 |

| Tychy | 1139.05 | 1096.39 | 1113.46 | 1084.89 | 1109.16 |

| Zabrze | 696.04 | 775.96 | 720.60 | 725.27 | 711.80 |

| Żory | 1104.48 | 1064.44 | 1075.43 | 1054.66 | 1141.07 |

| Dimension | Recommendations |

|---|---|

| Cooperation between the city authorities and residents | Inclusion of the issue of cooperation between authorities and residents in city strategies and allocation of separate task budgets for its implementation [59]. Ongoing communication between city authorities and residents aimed at decision-making transparency and strengthening trust. Consultation on urban development plans and large urban projects. Identification of the needs and expectations of different groups of residents. Monitoring of the quality of urban life. Creation of publicly accessible urban spaces conducive to the integration of different social groups. Organizing cultural and entertainment events that unite the urban community and strengthen the sense of belonging. Educating the city administration on the importance and forms of social participation. |

| Civic control | Developing online platforms for direct contact between residents and the city [42,43]. Organizing meetings with residents (e.g., from specific neighborhoods) to identify social problems and methods for solving them. Providing information about actions taken in response to citizen interventions and reports. |

| Civic budgets | Expanding the scope of civic budgets, including the inclusion of Smart City initiatives [41]. Extending the time horizon of participatory budgets and making them a permanent feature of the city’s strategy. Identifying inactive social groups and encouraging them to participate in decisions about urban infrastructure. |

| Openness of residents to diversity | Organizing meetings and workshops to integrate different groups of residents. Promoting tolerance and social empathy. Disseminating good practices and examples of diversity in the workplace, family, and school, and highlighting the benefits associated with them. |

| Counteracting exclusion | Identifying groups at risk of exclusion and systematically diagnosing and solving their problems. Designing universal infrastructure solutions that take into account the needs of all members of the urban community. Taking into account the needs of different groups of residents in spatial planning to prevent the creation of urban ghettos. Educating with a focus on eliminating fears of diversity and preventing exclusion. Organizing courses and training to prevent digital exclusion, which also limits opportunities for social participation [57]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jonek-Kowalska, I. Dimensions of Urban Social Sustainability: A Study Based on Polish Cities. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198615

Jonek-Kowalska I. Dimensions of Urban Social Sustainability: A Study Based on Polish Cities. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198615

Chicago/Turabian StyleJonek-Kowalska, Izabela. 2025. "Dimensions of Urban Social Sustainability: A Study Based on Polish Cities" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198615

APA StyleJonek-Kowalska, I. (2025). Dimensions of Urban Social Sustainability: A Study Based on Polish Cities. Sustainability, 17(19), 8615. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198615