1. Introduction

In recent years, the profound relationship between space and memory has attracted increasing attention in the field of social sciences. In cultural geography and anthropological studies, scholars generally regard space not merely as a material entity, but also as a carrier of human experience, emotion, and cultural practice [

1,

2,

3]. This perspective suggests that space and culture play a central role in the formation of collective memory and the construction of place identity: it not only embodies historical culture and emotions [

4,

5,

6], but also continuously reinforces group identity through everyday practices. Many studies have pointed out that individual memory is formed through collective interactions within the social structure and is a systematic memory constructed within specific social frameworks [

7,

8]. Pierre Nora [

9] further proposed the concept of “sites of memory”, emphasizing that space, as a composite of the material and the symbolic, crystallizes a group’s historical experiences and cultural identity. Dolores Hayden [

10] also pointed out that public landscapes not only record history, but also strengthen cultural belonging and social sentiment through their connection to local social practices.

Based on these theoretical foundations, the relationship between space and memory has increasingly been examined within the context of rapid social transformation. Particularly in the Chinese context, where urbanization and modernization are accelerating, rural areas are experiencing profound restructuring of their spatial structures and sociocultural systems. Development logics such as urban expansion and infrastructure renewal often disrupt original spatial configurations and local knowledge systems, thereby leading to the rupture of collective memory and the weakening of place identity [

11,

12]. Although collective memory is reconstructive in nature and can be transmitted across generations through cultural practices such as festivals, rituals, and oral traditions [

13,

14], current state-led memory construction mechanisms tend to favor a macro-level, unified narrative. This approach often overlooks the diverse memories rooted in everyday rural life and localized spatial experiences. Such neglect of locality, emotional resonance, and place-based practices has led to the gradual marginalization of grassroots memory ecologies amid the wave of modernization [

15,

16].

Compared to the drastic transformations in urban spaces, rural spaces exhibit greater structural stability and cultural resilience [

17], making them important sites for understanding cultural continuity. However, in the context of the ongoing Rural Revitalization Strategy, rural spaces are also facing increasing pressure of restructuring driven by state policies and market forces. The tension between cultural inheritance and spatial renewal is particularly pronounced in Historic and Cultural Towns. As spatial forms that concentrate local historical heritage and collective memory, these towns often lie at the “frontline intersection” of urban–rural integration. Their cultural identity is being reshaped between traditional local culture and modern planning logics [

18,

19]. These towns often concentrate historical architecture, traditional street layouts, ritual spaces, and folk activities, serving as core sites of local identity and collective memory [

20]. Although the 2002 Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Cultural Relics first formally recognized the legal status of “Historic and Cultural Towns,” thereby providing institutional support for local cultural resources [

21,

22], the continued intervention of modern planning models and commercial development has gradually marginalized the cultural functions of their public spaces, putting their memory-related attributes at risk of being diminished [

23,

24,

25]. Against the backdrop of rural economic transformation and intensified population mobility, this trend has become increasingly evident, with rural public spaces and collective memory showing signs of structural loosening [

26]. As Relph has pointed out, modernization should not come at the expense of local distinctiveness; rather, it should endow space with enduring meaning and warmth through cultural continuity, community participation, and human-centered design [

27].

The interactive relationship between collective memory and public space is a key perspective for understanding the above-mentioned transformation processes. Introduced into urban planning and sociology in the 1960s as a “borrowed concept” [

28,

29,

30], public space is regarded as an important medium for carrying local memory and cultural identity, and serves as a foundational element for the sustainable development of rural culture [

31,

32]. In rural society, public space not only hosts social practices such as rituals, gatherings, and interpersonal interactions, but also serves as a crucial platform for the materialization and intergenerational transmission of collective memory [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. However, memory is never a static repetition; rather, it is continuously reconstructed through the evolution of social structures and the shifting experiences of communities [

15,

38]. In this process, “generation”—as a group that shares specific historical events, cultural experiences, and social contexts—is regarded in sociology as an important structure influencing collective cognition [

15,

39]. Due to differences in upbringing, social experiences, and cognitive styles, different generational groups often exhibit significant divergence in their understanding, use, and emotional attachment to public space [

40,

41,

42]. It is precisely these intergenerational differences in the perception of place-based meaning, historical narratives, and cultural resources that intensify the fragmentation of collective memory and the destabilization of cultural identity during periods of social transformation. Therefore, examining collective memory through the dual dimensions of “space” and “generation” helps to reveal the complex functions of public space in memory construction and intergenerational transmission. It also offers an important theoretical perspective for understanding the cultural reconstruction and evolving mechanisms of identity in contemporary rural contexts.

Although existing studies have explored the relationship between collective memory and space from different disciplinary perspectives, their focuses vary. In sociology, Halbwachs emphasized that memory is embedded in social structures [

7], while Nora further highlighted the symbolic role of “sites of memory” in the construction of collective identity [

9]. In cultural geography, Hayden emphasized the power of place in identity construction [

10], while Connerton discussed how social practices sustain the continuity of memory [

13]. In urban studies, Mumford examined the relationship between the evolution of urban history and collective memory [

29]; Jacobs revealed the importance of community life in maintaining memory spaces [

30]; and Yang Mengjiao focused on how the renewal of traditional village spaces can activate collective memory [

43]. However, these studies still struggle to directly support the issues discussed in this paper. The research gap mainly lies in three aspects: firstly, most studies focus on urban spaces, emphasizing memory construction in urban communities or memorial sites [

44,

45], with insufficient attention given to rural areas, especially the spatial memory of historic and cultural towns. Secondly, existing studies have primarily focused on the functional attributes of public spaces, such as interaction, management, or landscape value, with insufficient attention given to their role in memory production, local identity, and cultural representation. Although a few scholars have begun to explore this direction: Chen Jianhua and Lu Shaoming studied space and memory using space syntax methods [

20,

46]; Azadeh Lak analyzed the process of memory reproduction in Tehran’s Baharestan Square [

24]; and Liu Tongyao examined the progressive adjustments of new rural public memory spaces [

47]. Overall, however, these studies remain scattered attempts and have yet to systematically reveal the mechanisms through which public space plays a role in the construction of collective memory and local identity. Lastly, in terms of research methods, existing studies often rely on archival analysis or macro-level narratives, lacking empirical methods that can demonstrate the spatialization, visualization, and intergenerational differences in collective memory. Especially at the level of regional practice, typical towns like Menghe, which both bear the responsibility of industrial development and cultural heritage preservation, have not yet entered the scope of relevant research. Building on these gaps, this study selects Menghe as a case, combining interviews and emotional mapping methods to explore how public space carries and reproduces collective memory through intergenerational interaction, aiming to complement and expand existing research.

Menghe Town embodies the dual characteristics of historical culture and industrial development. On the one hand, the legacy of the Qi-Liang medical school, clusters of traditional Chinese medicine residences, and ancient ancestral temples highlight its profound historical and cultural heritage; on the other hand, since the 1970s, the town has leveraged its locational advantages to develop into the “Famous Town of Automobile and Motorcycle Parts in China.” This hybrid configuration of cultural heritage and modern industry positions Menghe both as an important carrier of cultural transmission and as a site under considerable pressure from industrial expansion and spatial renewal. Both the Regulations on the Protection of Historic Cities, Towns, and Villages of Jiangsu Province and the 14th Five-Year Plan for the Integrated Development of Culture and Tourism in Changzhou call for balancing industrial development and heritage preservation in the process of modernization. They emphasize sustaining local memory through cultural–tourism integration, thereby providing the institutional background for this paper’s discussion of cultural inheritance and spatial renewal in Menghe Town.

In response to the above-mentioned theoretical and practical gaps, this study selects Menghe Town—a nationally designated Historic and Cultural Town in Changzhou, Jiangsu Province currently undergoing industrial transformation—as a representative case for empirical research. Through methods such as semi-structured interviews, emotional mapping, and intergenerational co-construction, this study aims to reveal the interaction mechanism between collective memory and public space in historical and cultural towns, and to explore how spatial transformation influences villagers’ cultural identity and sense of belonging. Specifically, the study is centered around the following core questions: (1) In the process of modernization, how do public spaces carry and transform the collective memory of Historic and Cultural Towns? (2) How does spatial transformation influence villagers’ cultural identity and sense of place? (3) What differences exist between generations in their perception of collective memory and use of space? By addressing these questions, the study not only deepens the understanding of cultural preservation and heritage transmission in historical towns under the background of modernization, but also provides practical insights for cultural protection and spatial renewal in the process of rural revitalization.

2. Research Area and Methods

To systematically address the three core questions raised in the introduction, this study establishes the following research objectives: to explore the relationship between representative public spaces and collective memory in Menghe Town, and to identify spatial nodes concentrated with emotional attachment and historical significance; to analyze the evolution of the village’s spatial structure and functions, revealing how spatial renewal reshapes villagers’ cultural identity and sense of belonging; and to compare intergenerational differences in memory content, spatial use, and emotional perception, ultimately proposing a “Narrate–Preserve–Participate” model for intergenerational co-construction.

Based on the above research objectives, this study adopts a combination of methods—including literature review, field investigation in the village, semi-structured interviews, emotional mapping, and memory index quantification—to reveal, from multiple perspectives, the bidirectional shaping mechanisms between collective memory and public space.

2.1. Menghe Town

2.1.1. Regional Overview

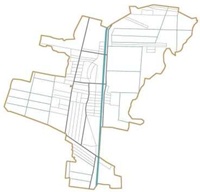

Menghe Town is located in the northwest of Changzhou City, Jiangsu Province, nestled between mountains and by the river, enjoying a unique geographical advantage. The town is renowned for its rich natural resources and beauty, earning the reputation of “a thousand acres of fertile soil and purple clay, and ten thousand acres of green fields.” The town covers a total area of 88.26 square kilometers, with 13 administrative villages and 4 communities under its jurisdiction. The permanent population is approximately 120,000. This study focuses on three representative research areas—Mengcheng Community, Wansui Community, and Nanlanling Village. The selection of cases is guided by the criteria of spatial morphology and cultural resource characteristics. Accordingly, both administrative villages and communities are incorporated as comparable grassroots spatial units in order to capture the diversity of spatial forms and cultural contexts within Menghe Town. To accurately present the diverse characteristics of collective memory and public space transformation in Menghe Town, the three selected research areas in this study exhibit notable typicality and complementarity in terms of spatial form, developmental stage, and cultural resources. These research areas respectively represent three typical rural spatial patterns—dispersed, linear–axial, and clustered settlement forms—encompassing different stages of development, from traditional agricultural villages to integrated industrial-agricultural communities and culture- and tourism-oriented communities. At the same time, each village retains a variety of historical and cultural resources, such as ancestral halls and temples, historic streets and alleys, and intangible cultural heritage. Together, they form the primary spatial carriers of cultural memory in Menghe Town and provide valuable case support for the study and practice of other Historic and Cultural Towns. The following are the construction conditions of the three sample research areas (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2):

On this basis, this study combines map interpretation and field investigation to analyze the spatial patterns of the three research areas (

Table 1). The classification of spatial types was defined primarily on the basis of residential density, the alignment of roads and water systems, and the coupling between settlements and natural elements, with reference to common typologies in settlement geography and rural planning studies. The three research areas present distinct spatial patterns: Nanlanling Village shows a dispersed form with interwoven roads, farmland, and residences; Wansui Community exhibits a linear pattern with houses aligned along main roads and farmland concentrated at the periphery; Mengcheng Community demonstrates a compact settlement pattern clustered around the historic district.

2.1.2. Historical Background

Since the first year of the Jianwu reign in the Eastern Han Dynasty, Menghe Town gradually prospered due to its access to river transport, becoming an important port that spurred population growth and trade development, eventually giving rise to several historic towns. Its administrative divisions have undergone multiple adjustments—from its early affiliation with Wujin County, to the establishment of Lanling Commandery during the Eastern Jin, to the Southern Lanling of the Southern Dynasties, and through various changes across the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties. In particular, the migration and development of the Xiao clan from Southern Lanling had a profound and lasting influence on Menghe. Since the Republic of China, Menghe has undergone several administrative reforms. In 1983, the People’s Commune system was abolished, and in 1999, it merged with Wansui Township. In 2003, it merged again with Xiaohe Town, and in 2013, further integration of village communities took place, ultimately forming the present-day Menghe Town, which is now part of the Xinbei District in Changzhou. In addition to inheriting traditional cultures such as Qi Liang culture and the Menghe Medical School, since the 1970s, Menghe has leveraged its advantageous geographical and industrial foundation to develop into a major production base for motorcycle and automobile parts in China, earning the title of “China’s Motorcycle and Automotive Parts Town.” It also occupies a prominent position in the Changzhou High-Tech Industrial Cluster. Meanwhile, its rich historical and cultural resources provide it with unique tourism potential.

Against this backdrop, the social composition of Menghe Town has become increasingly diversified, with villagers, migrant workers, and tourists together forming a heterogeneous research sample. This provides us with a more comprehensive perspective to analyze the relationship between collective memory and rural public spaces. This diverse population and rich cultural resources allow Menghe Town to maintain its deep cultural heritage while developing a modern economy. This provides an opportunity to explore the evolution of collective memory and public spaces in the context of a historic and cultural town, as well as their interactive relationship.

2.2. Research Methods

This study focuses on Menghe Ancient Town, aiming to explore the interactive relationship between collective memory and public space through the construction of a systematic research framework. As the core tool of the research, emotional mapping combines temporality, subjectivity, collectivity, and geography, and can visually present villagers’ emotional connections to spaces and the content of their memories [

48]. Collective memory is composed of both objective and subjective dimensions, including place, events/activities, history, and personal values/images [

47]. In the research process, the researcher combines semi-structured interviews with field surveys to identify the spiritual and material elements in the villagers’ collective memory. Villagers are then guided to mark relevant memory nodes on the map, thus creating a preliminary emotional map. The interview design combines in-depth interviews, field visits, and random interviews. Each session is controlled to last between 20 and 40 min, ensuring coverage of core topics such as memory collection, spatial positioning, spatial cognition, and emotional evaluation, thereby enhancing the comprehensiveness and effectiveness of the data. Oral history is a research method that collects, organizes, and preserves respondents’ verbal narratives of historical memories using tools such as recordings, audio, and video, based on specific research objectives [

49]. This research method is beneficial for constructing history around people. It focuses on excavating research materials that exist within the folk and the general public, thereby amplifying and transmitting the voices of the community, highlighting local culture and regional characteristics [

50]. The construction of emotional maps is based on the oral memories of villagers, combined with spatial field markings. This process dynamically updates the framework of emotional elements, thereby forming a visual expression of spatial identity. Building on this foundation, the study further focuses on the historical and cultural relics and landmark spaces in Menghe Ancient Town, such as temple courtyards, opera stages, and threshing grounds. It analyzes their fate in spatial transformation and their impact on villagers’ usage habits and emotional attachment.

In the context of rapid spatial updates, the villagers’ original collective memory often faces disruption due to physical demolition or functional replacement. However, even when the spatial forms change, villagers still tend to “patch” and rebuild memories through methods such as restoring old sites and objects and continuing traditional activities. These actions not only reflect emotional recognition of traditional spaces but also constitute the mechanism for the reconstruction of collective memory in new spaces. At the same time, the study introduces an intergenerational perspective. By comparing the interview content and emotional maps of three generations of villagers, it proposes a “Narrate—Preserve—Participate” memory co-construction model. Below is the research framework of this study (

Figure 3):

Figure 3 presents the logical framework of this study, distinguishing between two dimensions: “material elements” and “spiritual elements.” Through the method of emotional mapping, villagers’ memories are spatialized. “Memory continuity” refers to the activation of original emotional connections during spatial transformation through practices such as continued use or restoration of old sites. “Intergenerational co-construction” highlights how different age groups collaboratively shape memory spaces through storytelling and participation. Together, these components form the analytical model for examining the interaction between collective memory and public space.

2.3. Data Collection

This study primarily draws on three types of data: (1) documentary sources such as local chronicles and historical records; (2) spatial imagery collected through field observation and photography [

51]; and (3) memory data obtained from villagers through semi-structured interviews, along with emotional maps generated for analyzing the interaction between collective memory and public space.

A total of 297 individuals were interviewed, of whom 75 were selected for in-depth interviews, mainly including village cadres and long-term residents. The interview content covered aspects such as village history, daily activities, and emotional spaces. The respondents came from three research areas: 95 from Nanlanling Village, 97 from Wansui Community, and 105 from Mengcheng Community, ensuring a balanced sample structure. The interview group consisted of villagers, village leaders, and tourists, ensuring a multi-dimensional and multi-level source of information. At the same time, emotional maps were also created and collected during this process.

In China, there is no universally accepted standard for generational classification [

52], but in rural society, distinct generational characteristics emerge among different age groups due to variations in upbringing and social experience. To analyze intergenerational differences in collective memory, this study classifies villagers into three generations based on age structure and major historical turning points—such as the 1978 Reform and Opening-up and the acceleration of urbanization around the year 2000. Interviews and analysis were conducted accordingly. The first generation (aged 60 and above, born before 1964) experienced collectivization and institutional transition firsthand, with memories deeply rooted in traditional rural space and public life. The second generation (aged 36 to 60, born between 1965 and 1989) grew up during the early stages of de-collectivization and marketization, having lived through the household responsibility system, the rise of township enterprises, and labor migration; their memories intertwine traces of tradition with rapid social change. The third generation (aged 18 to 35, born between 1990 and 2007) was raised in an era of modernization and digitalization, with memories shaped more by individual experience and reflecting contemporary and pluralistic characteristics.

The specific intergenerational distribution in each research area is as follows: In Nanlanling Village, the interviewees included 24 first-generation villagers, 47 s-generation villagers, and 24 third-generation villagers. In Wansui Community, the respondents included 30 first-generation villagers, 45 s-generation villagers, and 22 third-generation villagers. In Mengcheng Community, the interviewees included 35 first-generation villagers, 50 s-generation villagers, and 20 third-generation villagers. Through a comprehensive analysis of the emotional maps and interview content from these three generations of villagers, the study ultimately constructs the overall emotional map of Menghe Ancient Town, summarizes the evolutionary trajectory of its collective memory, and reveals the different ways each generation perceives, emotionally connects to, and links to the history of public spaces. Below is the detailed sample structure information.

The sample shown in

Table 2 covers several typical communities within Menghe Ancient Town, encompassing various rural spatial patterns such as dispersed, axial-linear, and clustered settlement forms. In terms of development trajectories, the selected communities represent agricultural-based, industry-agriculture integrated, and cultural-tourism-oriented types, demonstrating strong representativeness and complementarity. The distribution of sample sizes across the communities is relatively balanced, and the generational composition includes older, middle-aged, and younger groups, generally meeting the requirements for intergenerational comparison. Although there are some differences in generational proportions among the communities, the overall structure remains reasonably sound, allowing for a meaningful reflection of key characteristics in spatial memory across generations.

2.4. Data Processing and Analytical Procedures

To ensure a clear and logical research process, the multi-source data collected in this study was systematically organized and analyzed in stages. The main steps include the following phases:

Firstly, the 297 collected interview transcripts from villagers were organized and analyzed to extract key statements related to historical memory, daily activities, spatial perception, and sensory experiences. Through keyword tagging and semantic categorization, a preliminary set of 145 emotionally charged and spatially oriented elements of intangible memory was identified. Based on clarity of content, spatial locatability, and frequency of occurrence, the above elements were further screened, merged, and categorized. In the end, 43 representative core memory elements were retained and grouped into four thematic dimensions according to their semantic characteristics: historical culture, behavioral activities, local industries, and sensory memory.

Secondly, at the spatial analysis level, the study employed the method of Emotional Mapping to systematically extract and locate memory spaces that appeared with high frequency in the interviews. Guided by the interview process, respondents marked spatial nodes that held personal or collective memory significance and rated each node on a scale from 1 to 5 (with 1 indicating weak emotional attachment and 5 indicating very strong emotional attachment) to represent the intensity of their emotional connection. The research team recorded and organized these spatial node data on-site, and then projected them onto a unified GIS base map. Using ArcGIS10.8.1 software, they performed map layer overlay and generated heatmaps to visualize the spatial distribution of memory density and emotional clustering areas, thereby providing a foundation for subsequent spatial classification and typological analysis. In this process, the color blocks in the emotional maps were generated based on frequency statistics of respondents’ marked points combined with spatial overlay analysis, in order to visualize the high-frequency clusters of villagers’ collective memory.

Lastly, based on the expressive differences among different generational groups, this study introduces the Element Salience Index (ESI) to measure the relative prominence of each memory element within intergenerational memory. This index helps identify spatial memory carriers that are highly representative and widely shared. The calculation formula is as follows:

Historical Culture Memory Element Significance Index:

Local Industry Memory Element Significance Index:

Behavioral Activity Memory Element Significance Index:

Sensory Memory Element Significance Index:

In this context, is the significance index (frequency) of the nth element in category x, where represents the number of mentions of the nth element in the category, is the total number of respondents who participated in the interview for that category and provided valid responses, and the subscripts h, l, b, and s represent the three categories: historical culture, behavioral activities, and sensory memory. Through this index, this study can objectively assess the influence of various memory elements within the structure of the villagers’ collective memory, providing a quantitative basis for subsequent memory-space matching, emotional map creation, and spatial identity analysis.

4. Discussion

In the process of rapid spatial restructuring, public spaces in villages have gradually become important sites for memory accumulation, emotional expression, and cultural identity. The study shows that spatial nodes with historical depth and strong social participation—often integrating functions such as interaction, ritual, and production—continue to serve as emotional cores of collective memory for villagers. These spaces not only carry the lived experiences of different generations but also continuously stimulate the reproduction of memory through festivals and everyday practices. According to the research findings, spatial nodes with a high concentration of memory are often composite places where material elements (such as physical space) are layered with spiritual elements (such as behavioral memory, ritual activities, and emotional experiences). It is precisely this integration of the physical and the symbolic—”space and meaning”—that makes them vital carriers for intergenerational sharing and the formation of collective identity. The memory hotspots revealed by the emotional maps reflect a memory network woven through the spatial structure, illustrating how public spaces gradually evolve into concrete carriers of collective memory and sites of identity formation through continued use, emotional engagement, and intergenerational layering. This process demonstrates that public space is not a static backdrop, but is continuously engaged in the processes of “carrying–transforming–reproducing” through social interaction, thereby constituting the interactive mechanism between collective memory and space.

With the advancement of industrial transformation and urbanization, many traditional spaces that once carried local identity are facing the challenges of functional decline or even disappearance. However, villagers have not passively accepted this transformation. Instead, they have actively “mended” the fractures in memory by restoring old sites, continuing traditional activities, and preserving local customs, thereby constructing an adaptive system of cultural identity. At the same time, a new generation of villagers is gradually forming emotional connections with modern plazas, street parks, and commercial nodes, reflecting a dynamic process of identity reconstruction and spatial readaptation. It can be seen that spatial transformation not only alters the physical environment but also profoundly shapes villagers’ cultural identity and sense of belonging: on the one hand, the weakening of traditional spaces leads to the erosion of the foundations of identity; on the other hand, emerging public spaces have become growth points for modern identity and social relationships.

Different generations exhibit distinct ways of perceiving and becoming attached to space. The older generation tends to regard traditional sites such as ancient buildings and farmland as the core of their memories, reflecting a strong emotional connection to the land and a deep sense of historical continuity. The middle generation, shaped by the “agriculture-to-industry” transition, sees everyday memory rooted in spaces where life and work intersect—such as factory buildings, alleyways, and small plazas. In contrast, the younger generation relies more on convenient, functional social spaces, with their memories often embedded in emerging nodes like bus stops, cultural and sports plazas, and riverside walkways. This result is similar to Wu Jinfeng’s study on generational differences in tourism spaces, which also found significant divergence in spatial preferences and identity across generations [

29]. However, the distinction here is that this study emphasizes the intertwining of “production–life–culture” within rural public spaces, rather than focusing solely on consumer-oriented tourism settings. These intergenerational differences in spatial usage have not led to cultural fragmentation; rather, through the interactive mechanism of “Narrate–Preserve–Participate,” they have facilitated the pluralistic construction and collaborative evolution of collective memory. As a result, public space has become a convergence point for intergenerational identity. These intergenerational differences are reflected not only in memory objects and spatial preferences, but also reveal the trajectory of transformation in cultural identity patterns: from clan lineage and attachment to the land, to industrial production and social interaction, and further to reliance on modern public life and functional convenience.

It is worth noting that these intergenerational memories are not only embedded in space but also manifest specific structural characteristics in spatial form. This study identifies three typical emotional spatial patterns: Centrally Aggregated Spaces, represented by core nodes such as historical buildings and village committee offices, predominantly carry the ritual memories and sense of community belonging among the older generation. In the process of spatial renewal, these areas should be enhanced in terms of their public interaction and festive functions so that they may continue to serve as focal points for intergenerational storytelling and cultural activities. Multi-nodal distributed spaces are widely located across everyday functional nodes such as alleyways, factory zones, and small marketplaces. These serve as the primary backdrop for the middle generation’s daily life and production activities. In the process of renewal, attention should be given to functional integration and scene transitions, improving the connectivity and adaptability of these nodes to create a flexible and continuous living network. Extended and permeable spaces are mainly distributed along waterfront roads, green pedestrian paths, and open urban blocks. Favored by the younger generation, these spaces emphasize leisure experience and a sense of fluidity. Renewal strategies should incorporate design approaches that enhance accessibility and interactivity—such as continuous walkways, visual corridors, and light-touch activity installations—to increase spatial friendliness and user engagement.

The combination of emotional mapping and interview narratives reveals a clear trend: the memory intensity of traditional spaces such as ancestral halls and farmland continues to decline, accompanied by a weakening of clan and production orientations; while the intensity of emerging public spaces such as squares, schools, and waterfront promenades increases, corresponding to a strengthening of public life and participation orientations. This indicates that the transformation of spatial functions not only changes the way spaces are used, but also reshapes cultural identity and sense of place. Intergenerational emotional mapping further highlights generational differences: the older generation relies on clans and land, the middle generation emphasizes transitional spaces, and the younger generation focuses more on modern public facilities. The spatial preferences and memory narratives of different generations layer upon each other, outlining the trajectory of cultural identity evolution—from clan ties and land bonds, gradually shifting to industrial production and social interactions, and eventually to modern public life and daily participation.

In conclusion, by revealing the mechanisms of interaction, analyzing identity and sense of belonging, and comparing intergenerational differences, this study demonstrates the cultural resilience and dynamic adaptability of Historic and Cultural Towns in the process of modernization. This not only provides new empirical support for the theoretical study of collective memory, but also echoes Relph’s discussion on the uniqueness of place and cultural identity [

21]. However, this paper places greater emphasis on the unique value of the “Narrate–Preserve–Participate” model in cross-generational collaboration, and further offers clear directions for the planning of rural public spaces and the transmission of culture.

6. Conclusions

This study takes Menghe Town in Changzhou as a case and systematically explores the evolution of collective memory and public spaces, as well as their interactive relationship, in the context of historic and cultural towns. Through semi-structured interviews, emotional map creation, and the construction of the intergenerational co-construction model, this study reveals villagers’ emotional attachment to different public spaces and their memory expression pathways throughout historical changes. The study found that collective memory not only shows significant differences between generations but also profoundly influences the usage patterns and identity construction of village public spaces.

The study further points out that with the updating of spatial forms and the weakening of traditional spaces’ functions, the memory-bearing capacity of public spaces is facing significant challenges. Through the “Narrate—Preserve—Participate” intergenerational co-construction model, villagers collectively reconstruct the memory network through narration, usage, and participation, providing dynamic support for the continuity of collective memory. The use of emotional maps effectively visualizes this process, achieving a bidirectional mapping between memory and space.

Collective memory, as a crucial support for the vitality of public spaces in historic and cultural towns, interacts and evolves with space in a way that not only reflects the path of cultural transmission but also reveals the mechanisms of local identity construction. Through thoughtful planning and cultural representation, public spaces can continue to play a core role in rural governance and cultural revitalization in the new era. This wil l promote the continuous improvement of the quality of public spaces in historic and cultural towns and the recreation of their cultural value.