Preserving the Past: Analyzing Structural Damage, Policy Implementation, and Conservation Efforts for 19th-Century Heritage Buildings in Peunayong, Aceh

Abstract

1. Introduction

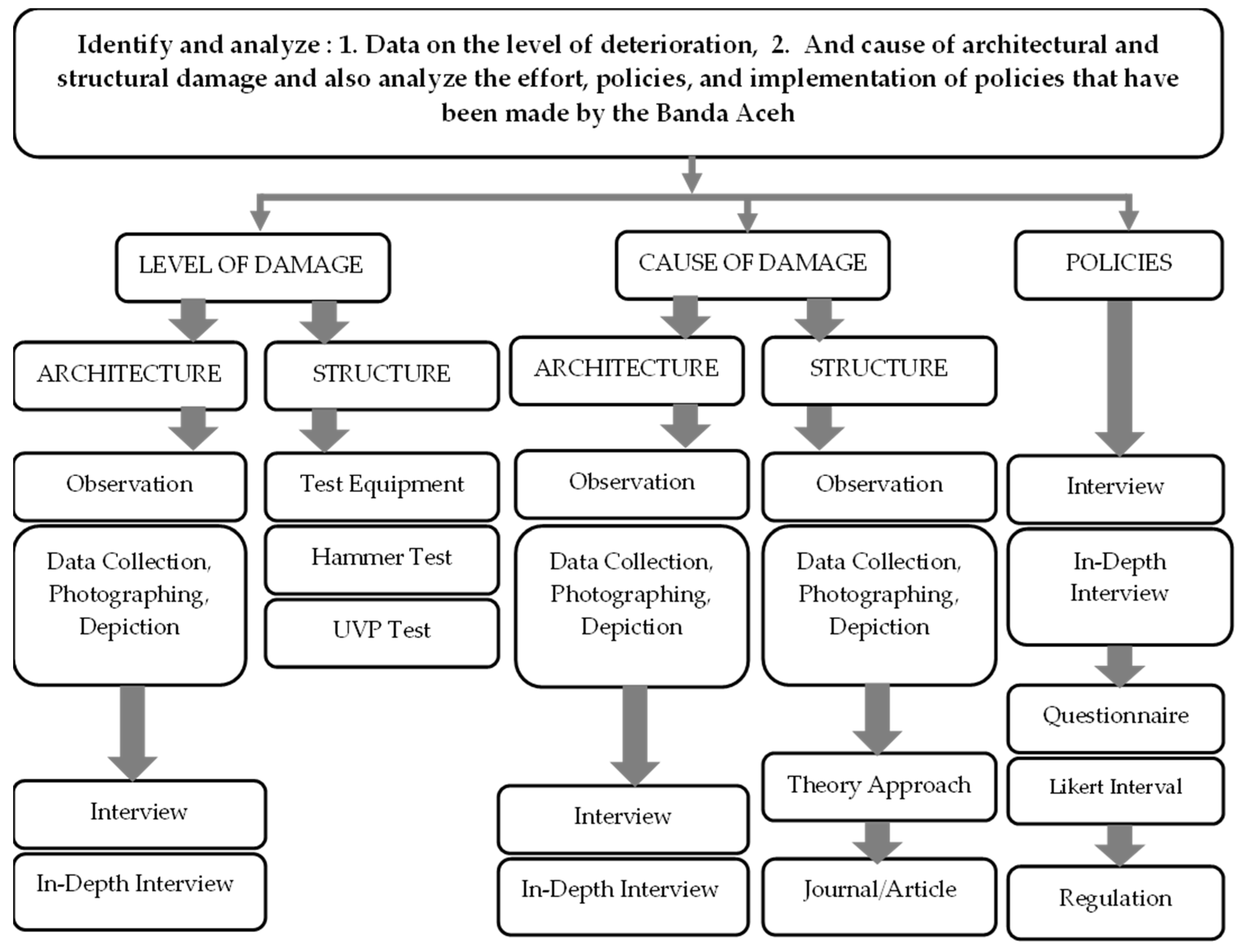

2. Materials and Methods

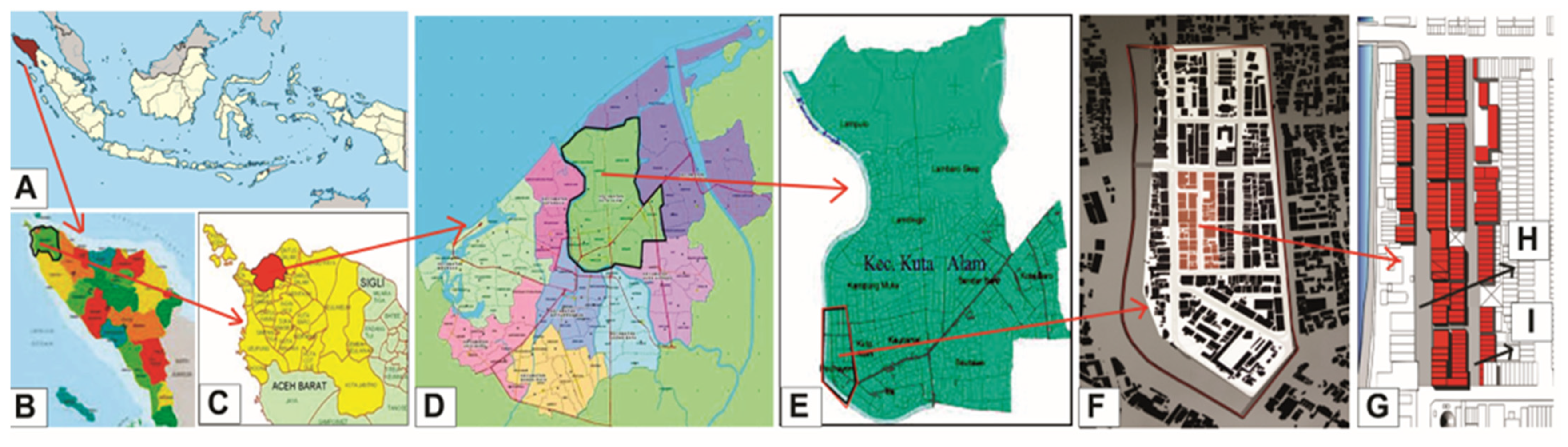

Research Location

- Minor or light damage (e.g., chipped paint, faded paint color, missing keys);

- Moderate or medium damage (e.g., broken window glass, loose or detached hinges, malfunctioning doors and windows, slight shrinkage, or outer-layer damage to columns);

- Severe or heavy damage: Components are no longer intact or incomplete, facade component materials have been replaced, component type models have been changed, and component dimensions have been changed. Wood components have been eaten by termites, and column structure has been damaged or altered by renovation.

- 1.

- Examining the architectural damage and its cause through observations

| Facade Damage Level | Score |

| Light-Damage Facade | 1 |

| Medium-Damage Facade | 2 |

| Heavy-Damage Facade | 3 |

| 1000 | +(670) | 1670 | =Light-Damage Facade |

| (1.670 + 1) = 1671 | +(670) | 2340 | =Medium-Damage Facade |

| (2340 + 1) = 2341 | +(670) | 3000 | =Heavy-Damage Facade |

- 2.

- Structural assessment

- 3.

- Policy analysis

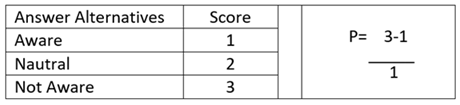

- Questionnaire: A total of 45 respondents, each representing one building unit, were involved. The questionnaire asked whether they were aware of government activities related to conservation, such as counseling, regulations, the preparation of SOPs for renovation, registration of heritage buildings for official recognition, funding support, and the existence of local conservation regulations. The majority of respondents indicated that they were not aware of these matters and stated that the government had never officially communicated with them regarding conservation.

- Interviews: Interviews were conducted with six local government agencies in Banda Aceh that hold responsibilities related to heritage buildings. The aim was to obtain detailed information on why conservation efforts have not been implemented for the 19 shophouse buildings in Peunayong, despite the area being designated as a cultural heritage zone in the Banda Aceh Regional Spatial Plan (RTRW 2009/2017) and the Detailed Spatial Plan (RDTR 2021–2041). These interviews also served to provide comparative data between the community questionnaire responses and the perspectives of government officials.

| 1000 | +(670) | 1670 | Aware |

| (1.670 + 1) = 1671 | +(670) | 2340 | Neutral |

| 2341 | +(670) | 3000 | Not Aware |

| A pristine 19th-century shophouse building unit | |

| Nonconforming renovated 19th-century shop building unit | |

| Light degree of damage | |

| Medium level of damage | |

| Heavy damage level | |

| Self-ownership | |

| Rental |

3. Results

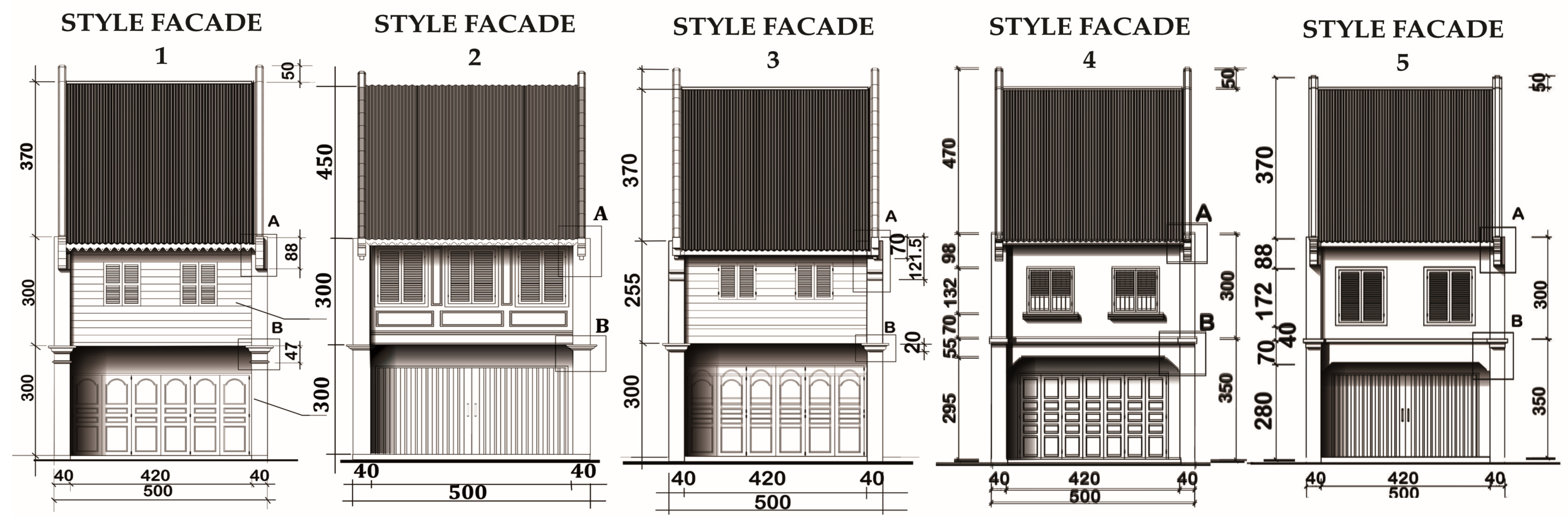

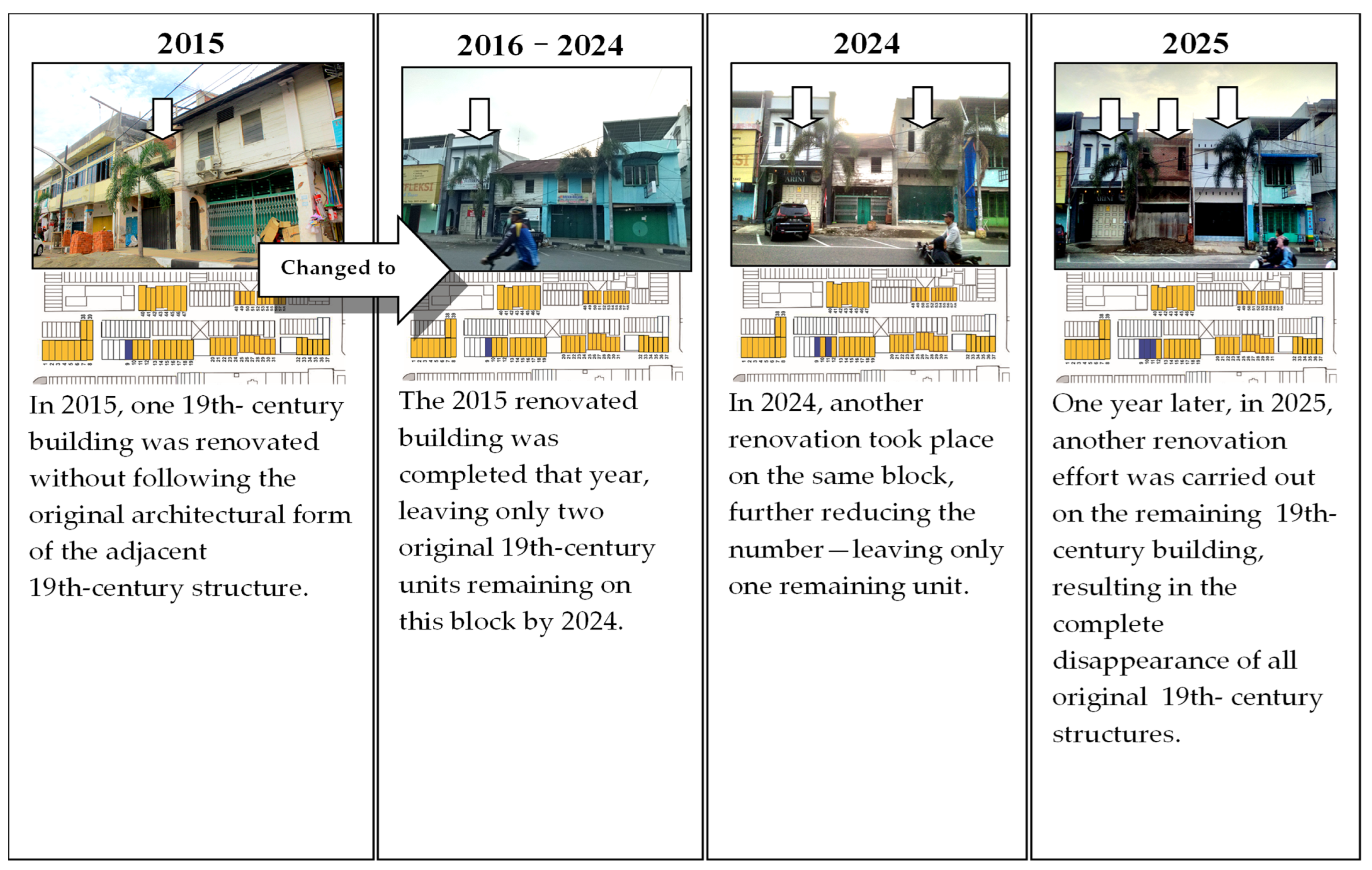

3.1. Architectural (Visual) Condition Survey

- 25 units (55.6%) retained original facade elements;

- 20 units (44.4%) underwent nonconforming renovations that altered their historical character (see Figure 6).

3.2. Damage Classification

| A pristine 19th-century shophouse building unit | |

| Nonconforming renovated 19th-century shop building unit | |

| Light degree of damage | |

| Medium level of damage | |

| Heavy damage level | |

| Self-ownership | |

| Rental |

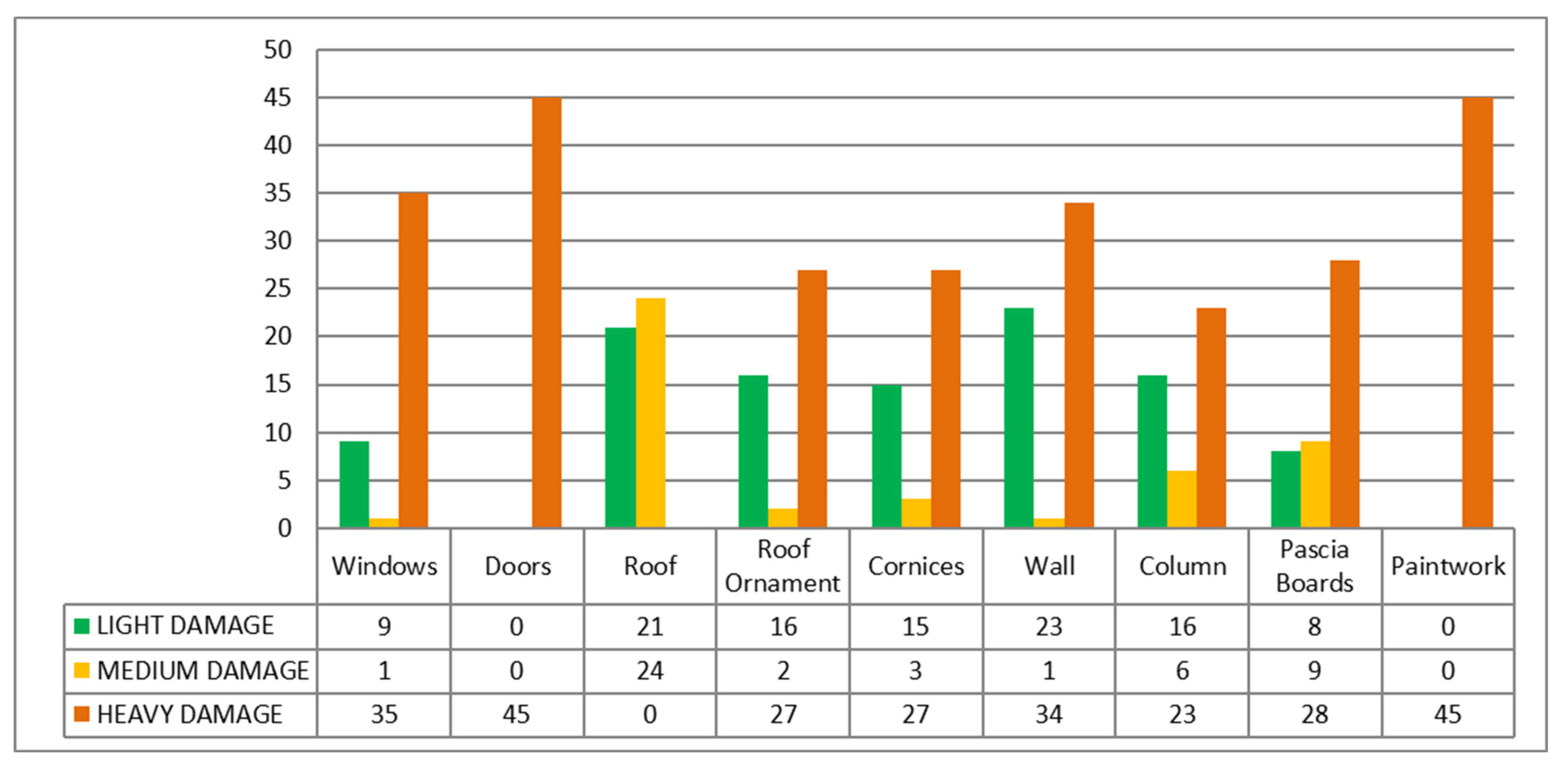

3.3. Classification of Structural Component Damage

4. Discussion

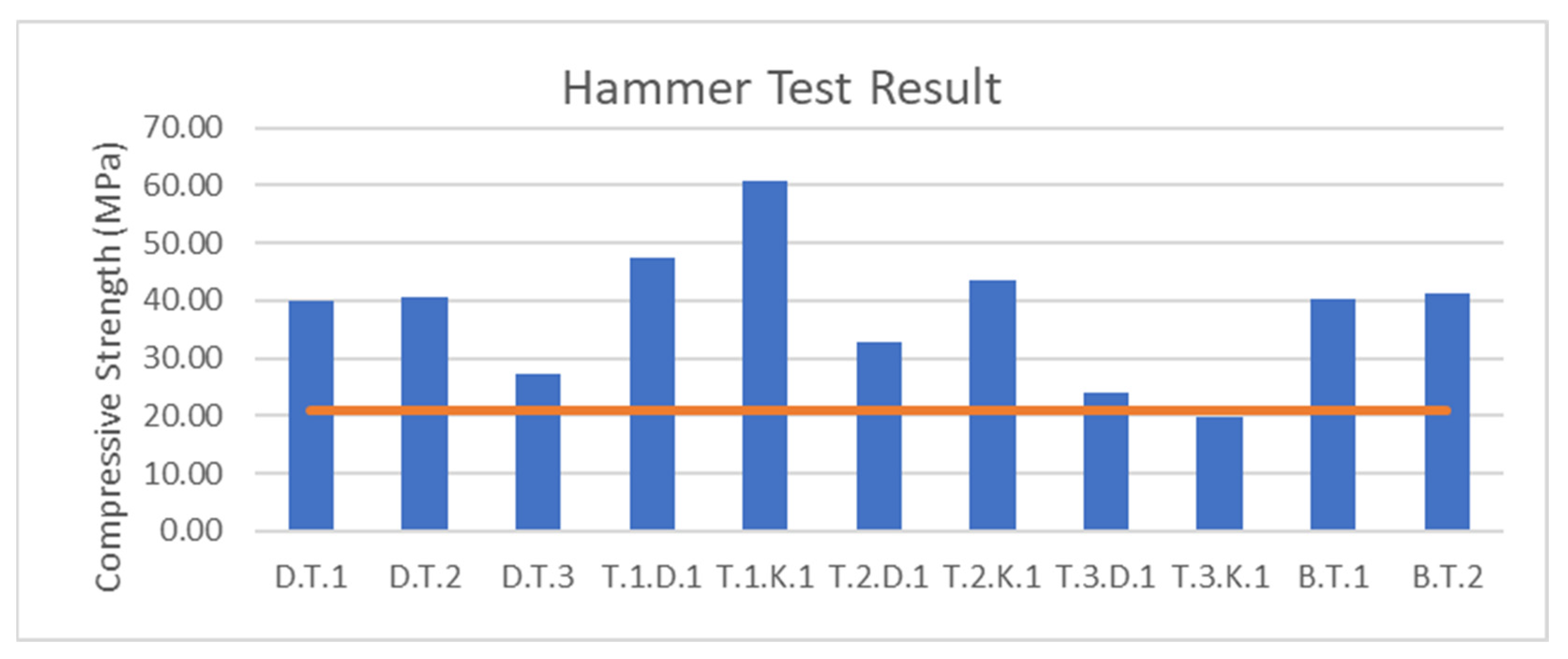

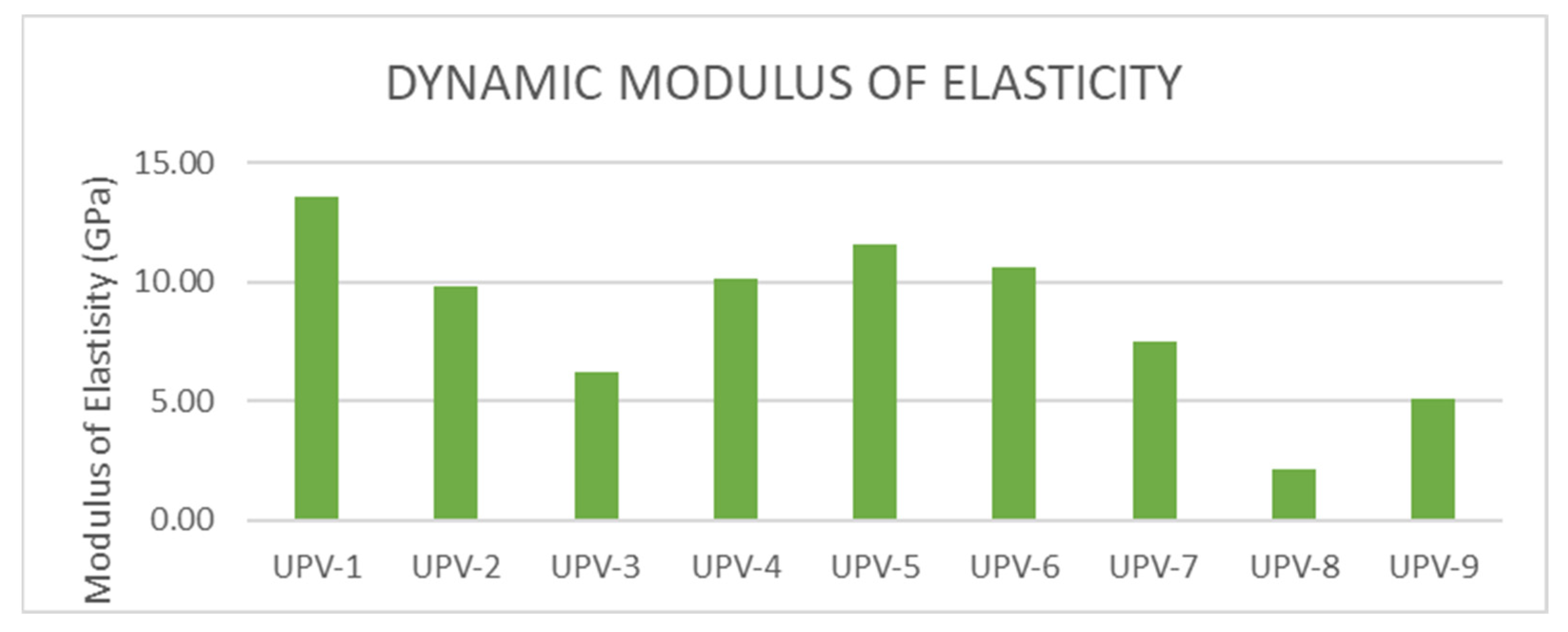

4.1. Facades’ Visual Condition and Structural Assessments

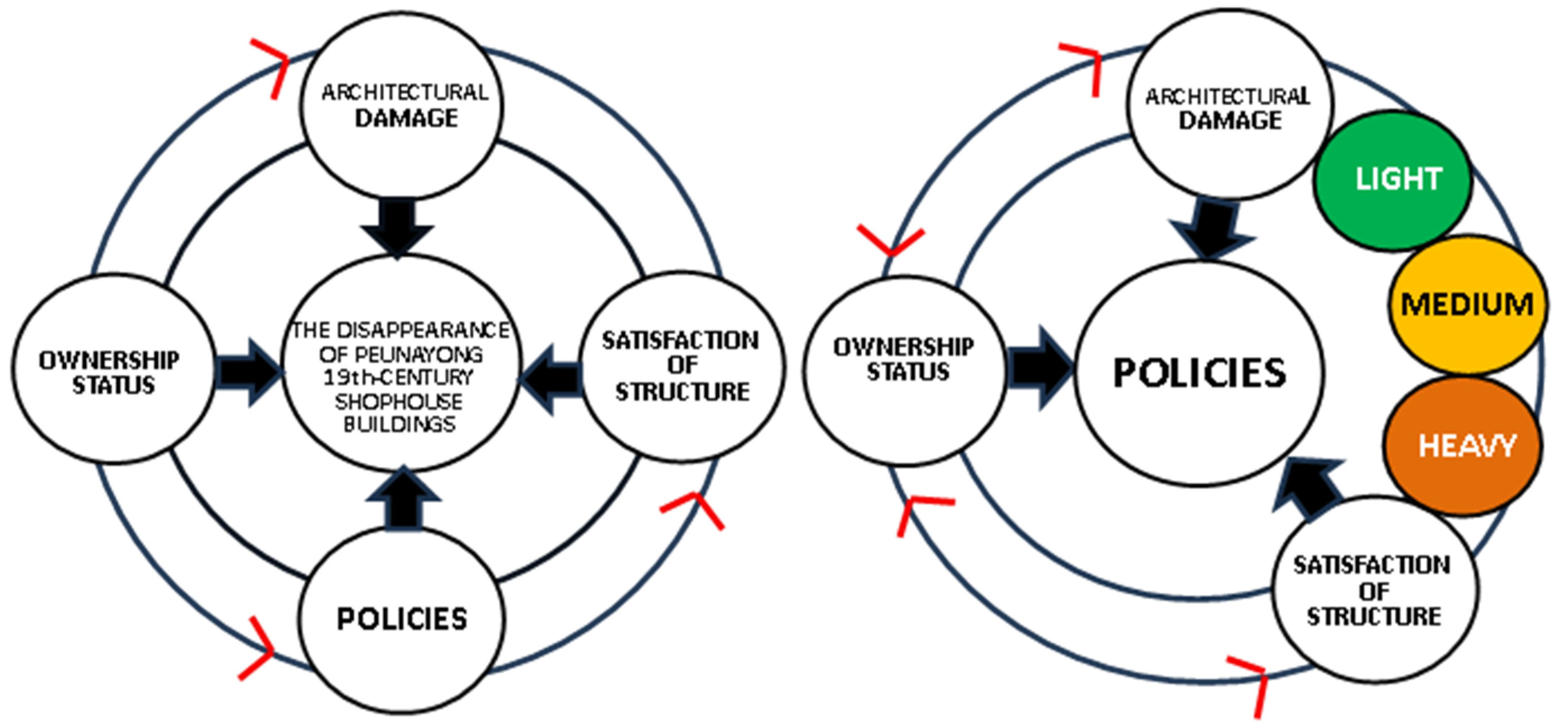

4.2. Causes of Damage

- 1.

- Environmental Factors

- Building Age: Constructed around 1874, many structures in Peunayong suffer from material degradation due to their old age.

- Natural Disasters: The 2004 tsunami significantly affected the area.

- Weathering: High humidity and pollution have led to decay of wooden and masonry components.

- 2.

- Human-Induced Factors

- Unregulated Renovation: Absence of official renovation guidelines or enforcement mechanisms led to inconsistent restorations.

- Ownership Patterns: As shown in Figure 15, out of 45 units, only 17 (37.8%) are privately owned, while the remaining 28 units (62.2%) are rental properties. This rental status contributes to a lack of maintenance, as tenants of the 19th-century shophouses are generally not responsible for or interested in renovating—resulting in continued deterioration due to human neglect.

- Long Lease Durations: Leases ranging from 1 to 30 years often lead to neglect and unauthorized alterations. Given the fact that 62.2% of all units are rentals, the situation was further exacerbated by long rental durations, which range from a minimum of 1–4 years to a maximum of 21–30 years.

- 3.

- Stakeholder and Policy Analysis

“Conservation and revitalization efforts have not been implemented because no instruction from above…, this have not been prioritized in the city policy. Furthermore, the Peunayong building is still owned by the community/private. They believe that cultural heritage issues are not within their purview, but rather the purview of the Ministry of Public Works and Housing (PUPR). Currently, they are unaware of the existence of standard operating procedures (SOPs) for implementation, regulations, and cooperation.” (Interview with Spatial Planning official).

- Non-Registration: The buildings are not officially listed as cultural heritage, limiting government intervention.

- No Local Guidelines: Despite recognition in Banda Aceh’s RTRW (2009/2017) and RDTR (2021–2041), no technical regulations (SOPs) exist to enforce conservation provided by PUPR (local government) in coordination with Badan Pelestarian Kebudayaan (BPK)/Heritage Conservation Board.

- Lack of Enforcement: A total of 100% of respondents claimed no awareness of specific heritage-related building regulations.

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- Policy Implementation Gap: The case of Peunayong highlights a profound disconnect between Indonesia’s Cultural Heritage Law No. 11/2010 and its actual implementation. Despite clear legal mandates, the shophouses remain unregistered and unprotected, reflecting an “implementation deficit” in heritage governance.

- 2.

- Weak Institutional Capacity: Heritage conservation is undermined by fragmented ownership, unclear responsibilities, and lack of technical guidelines or enforcement mechanisms—issues emblematic of broader governance challenges in Southeast Asia.

- 3.

- Beyond Material Preservation: Post-disaster realities reveal the limits of purely material-based conservation. Community needs, tenure insecurity, and economic pressures frequently take precedence over preservation principles.

- 4.

- Social Dimensions of Heritage: Ownership patterns, leasing practices, and the absence of community participation significantly shape conservation outcomes. Heritage policy must therefore integrate social and economic realities, not just architectural concerns.

- 5.

- From Reactive to Proactive Management: The findings call for a paradigm shift from ad hoc, reactive renovations toward proactive, integrated frameworks that combine legal protection, technical guidelines, and community engagement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Herzfeld, M. A Place in History: Social and Monumental Time in a Cretan Town; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1991; Available online: https://archive.org/details/placeinhistoryso0000herz/page/n3/mode/2up (accessed on 23 February 2024).

- UNESCO. Director-General, 2009-2017 (Bokova, I.G.) [Writer of Preface]. 2016. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000248073 (accessed on 24 February 2024).

- Choi, A.S.; Ritchie, B.W.; Papandrea, F.; Bennett, J. Economic valuation of cultural heritage sites: A choice modeling approach. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandarin, F.; Hosagrahar, J.; Albernaz, F.S. Why development needs culture. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serageldin, I. Global Public Goods: Cultural Heritage As Public Good. In Global Public Good: INTERNATIONAL Cooperation in the 21st Century; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999; pp. 240–263. ISBN 0-19-513051-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Obaidi, K.M.; Wei, S.L.; Ismail, M.A.; Kam, K.J. Sustainable building assessment of colonial shophouses after adaptive reuse in Kuala Lumpur. Buildings 2017, 7, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur Raqena, M.R.; Mimi Zaleha, A.G.; Yazid, S. Architectural heritage values and sense of place of Kampung Morten, Melaka. J. Malays. Inst. Plan. 2020, 18, 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ju, S.R.; Omar, S.B. A Typology of Modern Housing in Malaysia. Int. J. Hum. Ecol. 2010, 11, 109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Shahrul, Y.S.; Hasnizan, A.; Elma, D.I. Heritage Conservation and Regeneration of Historic Areas in Malaysia. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 105, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arazi, I.; Faris, K.; Mahmoud, S. Maintenance management framework for conservation of heritage buildings in Malaysia. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2010, 4, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eken, E.; Taşcı, B.; Gustafsson, C. An evaluation of decision-making process on maintenance of built cultural heritage: The case of Visby Sweden. Cities 2019, 94, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, G. Indigenous claims and heritage conservation: An opportunity for critical dialogue. Public Archaeol. 2005, 4, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth. Preservation, Conservation and Heritage: Approaches to the Past in the Present through the Built Environment. Asian Anthropol. 2011, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Research on Urban Heritage Conservation in the Wiew of People-Priented. Ph.D. Thesis, Shan Dong University, Jinan, China, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viollet-le-Duc, E. The Foundations of Architecture. Selections from the Dictionnaire Raisonné; George Braziller: New York, NY, USA, 1854. [Google Scholar]

- Pendlebury, J.; Short, M.; While, A. Urban World Heritage Sites and the problem of authenticity. Cities 2009, 26, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Venice Charter. International charter for the conservation and restoration of monuments and sites. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress of Architects and Technicians of Historic Monuments, Venice, Italy, 25–31 May 1964.

- Piagam Burra. In 1979, the Australia ICOMOS Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Significance Was Adopted at a Meeting of Australia ICOMOS. Available online: https://patinations.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/the-burra-charter.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Sutrisna, D. Peunayong, Kampung Lama Etnis Cina Di Kota Banda Aceh Balai Arkeologi Medan. 2008. Available online: http://www.balarmedan.wordpress.com/2008/06/18/peunayong-kampung-lama-etnis-cina-di-kota-bandaaceh (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Kusuma, W.; Hebing, H.M. Muslim Tionghoa Cheng Ho: Misteri Perjalanan Muhibah di Nusantara; Yayasan Pustaka Populer Obor’s: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2015; ISBN 978-979-461-785-4. [Google Scholar]

- Usman. Etnis Cina Perantauan di Aceh. Penerbit Yayasan Pustaka Obor Indonesia. 2009. Available online: https://books.google.co.id/books?id=oJTnQAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=oJTnQAAQBAJ&hl=id&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjgpsqtlvbnAhV77HMBHb5SBjIQ6AEIKjAA#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Lombard, D. Kerajaan Aceh Jaman Sultan Iskandar Muda (1607–1636); Jakarta: Balai Pustaka. 1991. Available online: https://archive.org/details/kerajaan-aceh-iskandar-muda (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Ismuha. Perkembangan Kota Banda Aceh Abad ke-16 Hingga Per-tengahan Abad ke-20. J. Ilm. Teknorona 1998, 1, 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Khol, D.G. Chinese Architec ture in The Straits Settlements and Western Malaya: Temples Kongsis and Houses; Heineman Asia: Kuala Lumpur, Archipel, 1984; Volume 33, p. 185. Available online: https://www.persee.fr/doc/arch_0044-8613_1987_num_33_1_2343 (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Viaro, M.A. Architectures of Indonesia: The Nias Island. Spaz. e Soc. 1992, 57, 110–121. [Google Scholar]

- Leumik, H. Kronologis Historis dan Dinamika Budaya Aceh; Perpustakaan Nasional Republik Indonesia: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- KohLim, W.G. Robert Home 1989 Of Planting and Planning: The making of British Colonial Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 1989; p. 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenny, F.; Mandasari, D. Analisa Karakter Kampung Pecinan di Kawasan Peradgangan dan Jasa Peunayong Pusat Kota Banda Aceh. J. Ruang. 2013, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar]

- Muftiad, I.; Irwansyah, M.; Azmeri. Revitalisasi Kawasan Pusat Kota Lama Peunayong untuk Mewujudkan Lingkungan yang Berklanjutan. J. Tek. Sipil 2015, 4, 128. [Google Scholar]

- Winarso, H.; Dewi, C. Urban Heritage Conservation Inaceh, Indonesia: Conserving Peunayong Fortourism. ASEAN J. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 9, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, C.; Nichols, J.; Izziah, I.; Mutia, E. Conserving the other’s heritage within Islamic society. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2021, 28, 444–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krier, R. Komposisi Arsitektur; Erlangga: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Burden, E. Building Facades: Faces, Figures, and Ornamental Detail; McGraw-Hill Professional: London, UK, 1996; ISBN 0070089590. Available online: https://www.rarebookstore.net/pages/books/569/building-facades-ernest-burden/building-facades-faces-figures-and-ornamental-details (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Wooi, T.Y. Penang Shophouses; a Handbook of Features and Materials; George Town World Heritage Incorporated: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Curl, J.S. Oxford Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, S.H.; Yahaya, S.R.C. Architecture and Heritage Buildings in Georgetown Penang; Penerbit Universiti Sains Malaysia: Pulau Pinang, Malaysia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zuraidi, S.N.F.; Abdul, R.M.A.; Akasah, Z.A. Measuring The Important Element of Defects in the Heritage Building. J. Inf. Syst. Technol. 2017, 2, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muftiadi, M.H.; Hasan, M.; Dewi, C.; Irwansyah, M.; Gheffira, G. Dentification facade of a 19th century shophouses in Peunayong, Banda Aceh. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1510, 012063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C805/C805M-18; Standard Test Method for Rebound Number of Hardened Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ASTM C597-22; Standard Test Method for Ultrasonic Pulse Velocity Through Concrete. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Delgado, E.; Manuera, J.L. Does Brand Trust Matter to Brand Equity? J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2005, 14, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaali, H. Psikologi Pendidikan; PT. Bumi Aksara: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2008; Available online: http://repository.fe.unj.ac.id/6076/8/Bibliography.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Burden, E. Illustrated Dictionary of Architectural Preservation; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wan Hashimah, W.I.; Shuhana, S. The Old Shophouses as Part of Malaysian Urban Heritage: The Current Dilemma. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of the Asian Planning Schools Association, Penang, Malaysia, 12–14 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Toong, Y.S.; Utaberta, N. Heritage Buildings Conservation Issues of Shophouses in Kuala Lumpur Chinatown. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2015, 747, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorfadhilah, M.B.; Shamzani, A.M.D. Documentation and conservation guidelines of Melaka heritage shophouses. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 50, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Farhana, N.A.; Ali, A.S.; Zaini, S.F.; Harumain, Y.A.S.; Abdullah, M.F. Character-defining elements of shophouses buildings in Taiping, Perak. J. Des. Built Environ. Spec. Issue 2017, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, A.S.; Muna, H.A.S. Penang/Georgetown’s shophouse façade and visual problems, analytic study. In Proceeding of the 4th International conference on Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 2016 (ICOLASS’16), Qatar, Doha, 30 January–1 February 2016; pp. 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Rodwell, D. Conservation and Sustainability in Historic Cities. 2007. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/296183497_Conservation_and_Sustainability_in_Historic_Cities#full-text (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Bullen, P.A.; Love, P.E.D. Adaptive reuse of heritage buildings. Struct. Surv. 2011, 29, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevoets, B.; Van, C.K. Adaptive reuse as an emerging discipline: An historic survey. In Reinventing Architecture and Interiors: A Socio-Political View on Building Adaptation; Cairns, G., Ed.; Libri Publishers: London, UK, 2013; pp. 13–32. ISBN 978-1-907471-64-3. [Google Scholar]

- Douglas, J. Building Adaptation; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2006; Available online: https://www.uceb.eu/DATA/CivBook/08.%20Building%20Adaptation.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2024).

- Langston, C.; Wong, F.K.W.; Hui, E.C.M.; Shen, L. Strategic assessment of building adaptive reuse opportunities in Hong Kong. Build. Environ. 2008, 43, 1709–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, E.H.K.; Chan, E.H.W. Implementation challenges to the adaptive reuse of heritage buildings: Towards the goals of sustainable, low carbon cities. Habitat Int. 2012, 36, 352–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study | Architectural/Facade Components | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [32] | Gates and entrances | Ground floor zone | Windows | Entrance | Guardrail | Roof and building finishes | Signs |

| [33] | Enclosure | Openings | Fenestration | Ornamentation | |||

| [34] | Enclosure | Openings | Fenestration | Ornamentation | |||

| [35] | Enclosure | Openings | Fenestration | Ornamentation | |||

| [36] | Enclosure | Openings | Fenestration | Ornamentation | |||

| [37] | Ceiling | Floor | Roof | Windows | Door | Wall | Ornamentation |

| Internal wall | External wall | Arch/lintel /hood | |||||

| Apron | |||||||

| Component Structure | |||||||

| Foundation | Column | Beam | Truss | Staircase | |||

| Number of building Units | Total Damage Level of Facade Components | Number of Facade Components | Total Score | Average (Number of Facade Components Multiplied by Total Score) | Damage to Facade | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light Damage | Medium Damage | Heavy Damage | |||||

| SCORE | |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Number of Building Units Multiplied by the Score | |||||||

| 1 | 7 × 1 = 7 | 0 | 2 × 3 = 6 | 9 | 7 + 0 + 6 = 13 | 1444 | Light Damage |

| 2 | 8 × 1 = 8 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 1 × 3 = 3 | 9 | 8 + 2 + 3 = 13 | 1444 | Light Damage |

| 3 | 8 × 1 = 8 | 0 | 1 × 3 = 3 | 9 | 8 + 0 + 3 = 11 | 1222 | Light Damage |

| 4 | 7 × 1 = 7 | 0 | 2 × 2 = 6 | 9 | 7 + 0 + 2 = 13 | 1444 | Light Damage |

| 5 | 7 × 1 = 7 | 0 | 2 × 3 = 6 | 9 | 7 + 0 + 2 = 13 | 1444 | Light Damage |

| 6 | 7 × 1 = 7 | 0 | 2 × 3 = 6 | 9 | 7 + 0 + 2 = 13 | 1444 | Light Damage |

| 7 | 7 × 1 = 7 | 0 | 2 × 3 = 6 | 9 | 7 + 0 + 2 = 13 | 1444 | Light Damage |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 15 | 1 × 1 = 1 | 3 × 2 = 6 | 5 × 3 = 15 | 9 | 1 + 6 + 5 = 22 | 2444 | Heavy Damage |

| 16 | 3 × 1 = 3 | 2 × 2 = 4 | 3 × 3 = 9 | 9 | 3 + 4 + 9 = 16 | 1778 | Light Damage |

| 17 | 1 × 1 = 1 | 3 × 2 = 6 | 6 × 3 = 18 | 9 | 1 + 6 + 18 = 25 | 2778 | Heavy Damage |

| 18 | 0 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 8 × 3 = 24 | 9 | 0 + 2 + 24 = 26 | 2889 | Heavy Damage |

| 19 | 2 × 1 = 2 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 2 + 0 + 27 = 29 | 3222 | Heavy Damage |

| 20 | 2 × 1 = 2 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 6 × 3 = 18 | 9 | 2 + 2 + 18 = 22 | 2444 | Heavy Damage |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 23 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 24 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 28 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 29 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 30 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 31 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 32 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 33 | 1 × 1 = 2 | 2 × 2 = 4 | 6 × 3 = 18 | 9 | 2 + 4 + 18 = 24 | 2667 | Heavy Damage |

| 34 | 4 × 1 = 4 | 1 × 2 = 1 | 4 × 3 = 12 | 9 | 4 + 1 + 12 = 17 | 1.889 | Light Damage |

| 35 | 5 × 1 = 5 | 0 | 4 × 3 = 12 | 9 | 5 + 0 + 12 = 17 | 1889 | Light Damage |

| 36 | 4 × 1 = 4 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 4 × 3 = 12 | 9 | 4 + 2 + 12 = 18 | 2111 | Medium Damage |

| 37 | 2 × 1 = 2 | 3 × 2 = 6 | 4 × 3 = 12 | 9 | 2 + 6 + 12 = 20 | 2222 | Medium Damage |

| 38 | 5 × 1 = 5 | 0 | 4 × 3 = 12 | 9 | 5 + 0 + 12 = 17 | 1889 | Light Damage |

| 39 | 6 × 1 = 6 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 1 × 3 = 3 | 9 | 6 + 2 + 3 = 11 | 1222 | Light Damage |

| 40 | 6 × 1 = 6 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 2 × 3 = 6 | 9 | 6 + 2 + 6 = 14 | 1556 | Light Damage |

| 41 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 42 | 0 | 0 | 9 × 3 = 27 | 9 | 27 | 3000 | Heavy Damage |

| 43 | 5 × 1 = 5 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 3 × 3 = 9 | 9 | 5 + 2 + 9 = 16 | 1778 | Light Damage |

| 44 | 5 × 1 = 5 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 3 × 3 = 9 | 9 | 5 + 2 + 9 = 16 | 1778 | Light Damage |

| 45 | 5 × 1 = 5 | 1 × 2 = 2 | 3 × 3 = 9 | 9 | 5 + 2 + 9 = 16 | 1778 | Light Damage |

| Building Units | (A) The Degree of Deterioration of Each Facade Component of the 19th-Century Shophouse | (B) Facade Damage Levels in 19th-Century Shophouses | (C) Building Ownership Status | ||||||||||||||

| Windows | Doors | Roof | Roof Ornament | Cornices | Wall | Column | Fascia Boards | Paintwork | Total Damage Level of Facade Components | Total Damage to Facade | Self- Ownership | Rental | |||||

| 1 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | 7 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | 8 | 0 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 5 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 6 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 7 | 7 | 0 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 15 | 1 | 3 | 5 | ||||||||||||||

| 16 | 3 | 2 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 17 | 1 | 3 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| 18 | 0 | 1 | 8 | ||||||||||||||

| 19 | 2 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 20 | 2 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 23 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 24 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 25 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 26 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 28 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 29 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 30 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 31 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 32 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 33 | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||||||

| 34 | 4 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 35 | 5 | 0 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 36 | 4 | 1 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 37 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 38 | 5 | 0 | 4 | ||||||||||||||

| 39 | 6 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 40 | 6 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| 41 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 42 | 0 | 0 | 9 | ||||||||||||||

| 43 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 44 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 45 | 5 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 9 | 0 | 21 | 16 | 15 | 23 | 16 | 8 | 0 | Total Component | Total façade (units) | Total Units | ||||||

| 108 | 46 | 264 | |||||||||||||||

| 1 | 0 | 24 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 6 | 9 | 0 | 17 | 28 | |||||||

| Light Damage | 15 | ||||||||||||||||

| 35 | 45 | 0 | 27 | 27 | 34 | 23 | 28 | 45 | Medium Damage | 2 | Percentage | ||||||

| Heavy Damage | 28 | 37.8% | 62.4% | ||||||||||||||

| Total Units | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 | Total Units | 45 | ||||||

| Number. | Question | Percentage % | Knowledge Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Did you know that the old shophouses include in the old city center area? | 80 | Do not know |

| 2 | Are you aware that Peunayong Old Town is designated as a heritage tourism area in the Banda Aceh Spatial Plan (2009–2029)? | 94 | Do not know |

| 3 | Do you know that Peunayong has been designated as a strategic area for rehabilitation and revitalization in the Banda Aceh City Spatial Plan (2009–2029)? | 96.5 | Do not know |

| 4 | Are you aware of any specific regulations governing the construction or renovation of buildings in the Peunayong heritage area? | 88 | Do not know |

| 5 | Are you aware of any government campaigns or outreach encouraging the preservation of the original form of old shophouses in Peunayong Old Town? | 86 | Do not know |

| 6 | Are you aware that when applying for a building permit (IMB) to construct or renovate, you are directed to follow the original façade design? | 89 | Do not know |

| 7 | Are you aware of local government officers prohibiting or warning those who construct or renovate buildings without following the original design? | 100 | Do not know |

| 8 | Do you know the purpose of painting heritage buildings in pink and blue? | 87 | Do not know |

| 9 | Are you aware of any SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures) for renovating buildings in this area? | 92.5 | Do not know |

| 10 | Are you aware if the government has ever offered or provided incentives for the maintenance of old shophouses in Peunayong Old Town? | 93 | Do not know |

| Average public knowledge level (total percentage 906/10 questions) = 90.6% (final percentage) | Do not know | ||

| Stakeholder | Current Role/ Position | Problem/Gap | Needed Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Government (Municipality/Spatial Planning Office) | Recognizes Peunayong’s cultural significance in RTRW (2009–2029) and RDTR (2021–2041). | No enforceable SOPs or conservation guidelines; conservation “not prioritized in city policy” (interview with Spatial Planning official). Lack of coordination and clear job descriptions. | Formally register shophouses as heritage assets; develop SOPs for renovation/maintenance; prioritize heritage in urban policy agendas; coordinate across departments. |

| Badan Pelestarian Kebudayaan (BPK) and PUPR | Considered by local officials as responsible for cultural heritage conservation. | Disconnected from local-level implementation; absence of financial or technical support mechanisms for Peunayong. | Provide technical assistance, funding mechanisms, and regulatory models for local adoption; establish shared responsibility frameworks. |

| Private Owners | Hold legal ownership of ~37.8% of buildings. | Lack incentives to preserve; prioritize profit-driven renovations; no legal obligation to follow conservation standards. | Provide tax reliefs, subsidies, or grants for conservation; require adherence to conservation SOPs; promote adaptive reuse with incentives. |

| Tenants/Renters | Long-term leaseholders (62.2% of units) responsible for day-to-day use. | Lack of incentives for conservation; tend to neglect routine maintenance; engage in unsympathetic alterations. | Introduce contractual conservation clauses in rental agreements; provide awareness programs on heritage value. |

| Community/Civil Society | Currently marginal role in conservation. | Lack of awareness and engagement; perceive heritage as government responsibility. | Foster community participation through awareness campaigns, heritage tourism initiatives, and participatory planning. |

| Academics and NGOs | Provide studies, surveys, and advocacy. | Limited influence in policy enforcement; recommendations not institutionalized. | Strengthen partnerships with government; integrate research findings into planning and public awareness. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Muftiadi; Hasan, M.; Dewi, C.; Irwansyah, M. Preserving the Past: Analyzing Structural Damage, Policy Implementation, and Conservation Efforts for 19th-Century Heritage Buildings in Peunayong, Aceh. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198594

Muftiadi, Hasan M, Dewi C, Irwansyah M. Preserving the Past: Analyzing Structural Damage, Policy Implementation, and Conservation Efforts for 19th-Century Heritage Buildings in Peunayong, Aceh. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198594

Chicago/Turabian StyleMuftiadi, Muttaqin Hasan, Cut Dewi, and Mirza Irwansyah. 2025. "Preserving the Past: Analyzing Structural Damage, Policy Implementation, and Conservation Efforts for 19th-Century Heritage Buildings in Peunayong, Aceh" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198594

APA StyleMuftiadi, Hasan, M., Dewi, C., & Irwansyah, M. (2025). Preserving the Past: Analyzing Structural Damage, Policy Implementation, and Conservation Efforts for 19th-Century Heritage Buildings in Peunayong, Aceh. Sustainability, 17(19), 8594. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198594