A Review of Current Substitution Estimates for Buildings with Regard to the Impact on Their GHG Balance and Correlated Effects—A Systematic Comparison

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. General

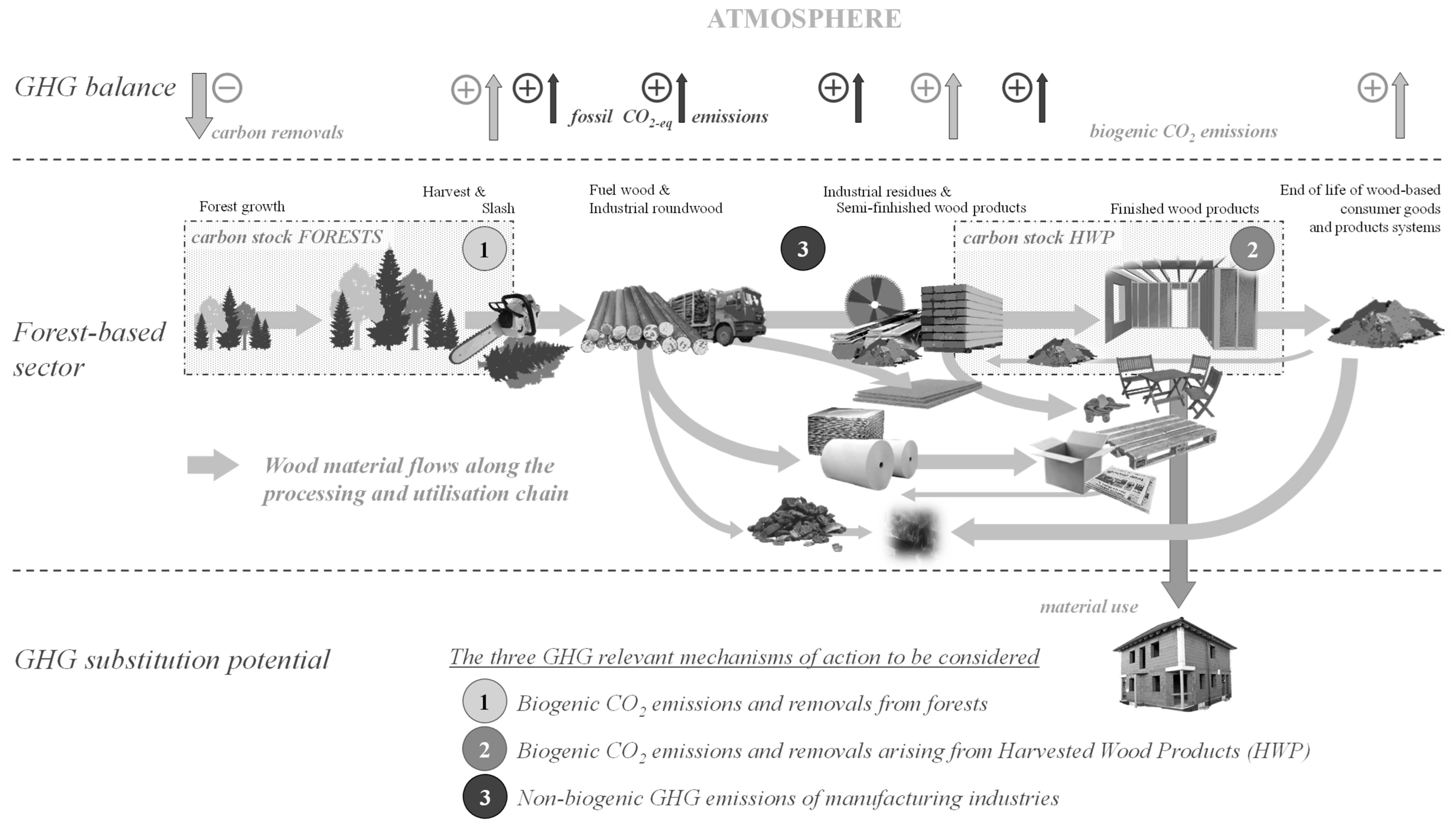

1.2. GHG Relevance of Wood

1.3. GHG Substitution Potential

1.4. Objectives of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Describtion of Indicators: General Conditions

2.2. Describtion of Indicators: Outcome

2.3. Describtion of Indicators: Scaling Effects

3. Results

3.1. General Conditions

3.1.1. Product Level

3.1.2. Building Level

- Modules A + C + D [47]

3.2. Outcome

3.2.1. Product Level

3.2.2. Building Level

- tCO2e/tC [44]

- Timber and steel [45]

3.3. Scaling Effects

3.3.1. Product Level

3.3.2. Building Level

3.4. Summary of Findings

4. Discussion

4.1. General Conditions

4.2. Outcome and Scaling Effects

4.3. Potential Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BAU | Business-As-Usual |

| CLT | Cross-Laminated Timber |

| CRFC | Certification framework for permanent carbon removals, carbon farming and carbon storage in products |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declarations |

| EPS | Expanded polystyrene |

| EU | European Union |

| GEA | Gross external area |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| HWP | Harvested wood product |

| ICE | Inventory of Carbon and Energy |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| LCI | Life cycle inventory |

| LULUCF | Land use, land use change and forestry |

| MFH | Multi-family house |

| RC | Reinforced concrete |

| SFH | Single-family house |

| SP | Substitution potential |

| TFH | Two-family house |

| UNFCCC | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change |

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; p. 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Environment Programme (UNEP). Global Status Report for Buildings and Construction; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. In A Renovation Wave for Europe-Greening Our Buildings, Creating Jobs; Improving Lives: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Röck, M.; Prister’a, G.; Ramon, D.; Van de Moortel, E.; Mouton, L.; Kockat, J.; Toth, Z.; Allacker, K. Science for policy: Insights from supporting an EU roadmap for the reduction of whole life carbon of buildings. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1363, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. European Green Deal. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/story-von-der-leyen-commission/european-green-deal_en (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Regulation (EU) 2024/3012 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 November 2024 Establishing a Union Certification Framework for Permanent Carbon Removals, Carbon Farming and Carbon Storage in Products. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/3012/oj/eng (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Directive (EU) 2023/1791 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 September 2023 on Energy Efficiency and Amending Regulation (EU) 2023/955 (Recast). 2023. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/dir/2023/1791/oj/eng (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- European Union. New European Bauhaus Initiative. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/index_en (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. Federal Climate Action Act (Bundes-Klimaschutzgesetz–KSG). 2024. Available online: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_ksg/englisch_ksg.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection. Federal Action Plan on Nature-Based Solutions for Climate and Biodiversity; Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection: Berlin, Germany, 2023.

- Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building, & Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture. Wood Construction Initiative: Strategy of the Federal Government for Promoting Climate-Smart and Resource-Efficient Timber Construction. Available online: https://www.bmleh.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/DE/Broschueren/holzbauinitiative.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=11 (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Özdemir, Ö.; Hartmann, C.; Hafner, A.; König, H.; Lützkendorf, T. Next generation of life cycle related benchmarks for low carbon residential buildings in Germany. Next Generation of Life Cycle Related Benchmarks for Low Carbon Residential Buildings in Germany. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1078, 012053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüter, S. Abschätzung von Substitutionspotentialen der Holznutzung und ihre Bedeutung im Kontext der Treibhausgas-Berichterstattung. [Estimation of Substitution Potentials of Wood Utilisation and Their Significance in the Context of Greenhouse Gas Reporting]; Thünen Working Paper 214; Johann Heinrich von Thünen-Institut: Braunschweig, Germany, 2023; p. 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCCC. Report of the Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement on the Third Part of Its First Session, Held in Katowice from 2 to 15 December 2018. Addendum Part two: Action taken by the Conference of the Parties Serving as the Meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement, FCCC/PA/CMA/2018/3/Add.1. 2019. Available online: https://unfccc.int/documents/193407 (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Rüter, S. The Contribution of the Material Wood Use to Climate Protection-the WoodCarbonMonitor Model (de). Ph.D. Thesis, Center of Life and Food Sciences Weihenstephan, Technical University of Munich, Munich, Germany, 2017; p. 270. [Google Scholar]

- Rüter, S.; Matthews, R.W.; Lundblad, M.; Sato, A.; Hassan, R.A. Harvested Wood Products. 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use IPCC: Switzerland, 2019; Chapter 12, Volume 4, p. 49. Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/vol4.html (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- ISO 21930; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Core Rules for Environmental Product Declarations of Construction Products and Services. International Organization for Standardization: Generva, Switzerland, 2017.

- EN 15804; Sustainability of Construction Works-Environmental Product Declarations-Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2022.

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2006.

- Hafner, A.; Özdemir, Ö. Comparative LCA study of wood and mineral non-residential buildings in Germany and related substitution potential. Eur. J. Wood Wood Prod. 2022, 81, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.; Schäfer, S. Comparative LCA study of different timber and mineral buildings and calculation method for substitution factors on building level. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 167, 630–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskinen, P.; Cardellini, G.; González-García, S.; Hurmekoski, E.; Sathre, R.; Seppälä, J.; Smyth, C.; Stern, T.; Verkerk, P.J. Substitution effects of wood-based products in climate change mitigation. Sci. Policy 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.; Rüter, S.; Ebert, S.; Schäfer, S.; König, H.; Cristofaro, L.; Diederichs, S.; Kleinhenz, M.; Krechel, M. Treibhausgasbilanzierung von Holzgebäuden-Umsetzung Neuer Anforderungen an Ökobilanzen und Ermittlung Empirischer Substitutionsfaktoren (THG-Holzbau). [Greenhouse Gas Balancing of Timber Buildings-Implementation of New Requirements for Life Cycle Assessments and Determination of Empirical Substitution Factors]; Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Ressourceneffizientes Bauen: Bochum, Germany, 2017; p. 148. ISBN 978-3-00-055101-7. [Google Scholar]

- EN 15978; Sustainability of Construction Works-Assessment of Environmental Performance of Buildings-Calculation Method. DIN Media: Berlin, Germany, 2011.

- ISO 21931-1; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Framework for Methods of Assessment of the Environmental, Social and Economic Performance of Construction Works as a Basis for Sustainability Assessment. International Organization for Standardization: Generva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Sathre, R.; O’Connor, J. Meta-analysis of greenhouse gas displacement factors of wood product substitution. Environ. Sci. Policy 2010, 13, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyle, M.; Braet, J.; Audenaert, A. Life cycle assessment in the construction sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza, L.; Rincón, L.; Vilarino, V.; Pérez, G.; Castell, A. Life cycle assessment (LCA) and life cycle energy analysis (LCEA) of buildings and the building sector: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 394–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodoo, A.; Gustavsson, L.; Sathre, R. Lifecycle primary energy analysis of conventional and passive houses. Int. J. Sustain. Build. Technol. Urban Dev. 2012, 3, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeren, N.; Mutel, C.; Steubing, B.; Ostermeyer, Y.; Wallbaum, H.; Hellweg, S. Environmental Impact of Buildings-What Matters? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 9832–9841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, H. Carbon storage and CO2 substitution in new buildings. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Built Environment Conference 2016 in Hamburg: Strategies, Stakeholders, Success Factors, Hamburg, Germany, 7–11 March 2016; pp. 62–63. [Google Scholar]

- Takano, A.; Hughes, M.; Winter, S. A multidisciplinary approach to sustainable building material selection: A case study in a Finnish context. Build. Environ. 2014, 82, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14067; Greenhouse Gases—Carbon Footprint of Products—Requirements and Guidelines for Quantification. International Organization for Standardization: Generva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Smyth, C.; Rampley, G.; Lemprière, T.C.; Schwab, O.; Kurz, W.A. Estimating product and energy substitution benefits in national-scale mitigation analyses for Canada. Glob. Change Biol. Bioenergy 2017, 9, 1071–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmgren, P. Fossil Displacement and Value Chain Emissions Related to Primary Wood-Based Products in Ireland. 2021. Available online: https://www.coillte.ie/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Holmgren-Report.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Valsta, L.; Poljatschenko, V. Carbon emissions displacement effect of Finnish mechanical wood products by dominant tree species in a set of wood use scenarios. Silva Fenn. 2021, 55, 10391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayo, C.; Noda, R. Climate Change Mitigation Potential of Wood Use in Civil Engineering in Japan Based on Life-Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2018, 10, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amico, B.; Pomponi, F.; Hart, J. Global potential for material substitution in building construction: The case of cross laminated timber. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 279, 123487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Humpenöder, F.; Churkina, G.; Reyer, C.P.O.; Beier, F.; Bodirsky, B.L.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; Lotze-Campen, H.; Popp, A. Land use change and carbon emissions of a transformation to timber cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Rivera, A.; Amor, B.; Blanchet, P. Evaluating the Link between Low Carbon Reductions Strategies and Its Performance in the Context of Climate Change: A Carbon Footprint of a Wood-Frame Residential Buildings in Quebec, Canada. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Gu, H.; Bergman, R.D.; Liang, S. Comparative Life-Cycle Assessment of a High-Rise Mass Timber Building with an Equivalent Reinforced Concrete Alternative Using the Athena Impact Estimator for Buildings. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himes, A.; Busby, G. Wood buildings as a climate solution. Dev. Built Environ. 2020, 4, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Ter-Mikaelian, M.T.; Yang, H.; Colombo, S.J. Assessing the greenhouse gas effects of harvested wood products manufactured from managed forests in Canada. Forestry 2018, 91, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.; D’Amico, B.; Pomponi, F. Whole-life embodied carbon in multistory buildings. J. Ind. Ecol. 2021, 25, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crafford, P.L.; Wessels, C.B. South African log resource availability and potential environmental impact of timber construction. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2020, 116, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustavsson, L.; Nguyen, T.; Sathre, R.; Tettey, U.Y.A. Climate effects of forestry and substitution of concrete buildings and fossil energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 136, 110435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, A.; Ottelin, J.; Sorvari, J.; Junnila, S. Cities as carbon sinks—Classification of wooden buildings. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 094076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodoo, A. Lifecycle Impacts of Structural Frame Materials for Multi-storey Building Systems. J. Sustain. Archit. Civ. Eng. 2019, 24, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Sandanayake, M.; Lokuge, W.; Zhang, G.; Setunge, S.; Thushar, Q. Greenhouse gas emissions during timber and concrete building construction—A scenario based comparative case study. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 38, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Liu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Huang, H.; Sun, C.; Shao, Y. A Comparison of the Energy Saving and Carbon Reduction Performance between Reinforced Concrete and Cross-Laminated Timber Structures in Residential Buildings in the Severe Cold Region of China. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, D.; Ding, G. Comparing the performance of brick and timber in residential buildings–The case of Australia. Energy Build. 2018, 159, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitz, A.; Griffin, C.T.; Dusicka, P. Comparing the embodied carbon and energy of a mass timber structure system to typical steel and concrete alternatives for parking garages. Energy Build. 2019, 199, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.; Rüter, S. Method for assessing the national implications of environmental impacts from timber buildings-an exemplary study for residential buildings in Germany. Wood Fibre Sci. 2018, 50, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spear, M.; Hill, C.; Norton, A.; Price, C. Wood in Construction in the UK: An Analysis of Carbon Abatement Potential Extended Summary. 2019. Available online: https://www.theccc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Wood-in-Construction-in-the-UK-An-Analysis-of-Carbon-Abatement-Potential-BioComposites-Centre.pdf (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Geng, A.; Chen, J.; Yang, H. Assessing the Greenhouse Gas Mitigation Potential of Harvested Wood Products Substitution in China. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1732–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astle, P.; Gibbons, L.; Eriksen, A. Comparing differences in building life cycle assessment methodologies. Ramboll 2023. Available online: https://brandcentral.ramboll.com/share/Xq3jpUKSqvPu5dpmRaDs/assets/44376 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Hafner, A.; Schäfer, S.; Krause, K. Impact of Different Reference Study Periods in Life Cycle Analysis of Buildings on Material Input and Global Warming Potential: Emphasis on Sustainable Civil Infrastructure; Taylor & Francis Group: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steubing, B.; Wernet, G.; Reinhard, J.; Bauer, C.; Moreno Ruiz, E. The ecoinvent database version 3 (part II): Analysing LCA results and comparison to version 2. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2016, 21, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, N.; Heinonen, J.; Marteinsson, B.; Säynäjoki, A.; Junnonen, J.-M.; Laine, J.; Junnila, S. A life cycle assessment of two residential buildings using two different LCA database-software combinations: Reconizing unifomities and inconsistencies. Buildings 2019, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building. Ökobuadat. Available online: https://www.oekobaudat.de/no_cache/en/database/search.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

| General Conditions | Outcome | Scaling Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Sector Background of Authors | Definition of Substitution Potential | Scaling Level |

| Scope of Application | GHG Substitution Potential | Period/Date |

| Region | Comparative Values of Substitution | Reference Scenario |

| Standards | GHG Emission Reductions | Scenarios |

| System Boundaries | Biogenic Carbon Storage | Calculation Rules |

| Reference Study Period | GHG Emission Reductions | |

| LCA Background Data and Database | Biogenic Carbon Storage | |

| Functional Units and der Equivalence |

| GENERAL CONDITIONS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Sector Background of Authors | Region | Standards | System Boundaries (Modules) | Reference Study Period | LCA Background Data and Database | Functional Units and Their Equivalence | Reference | ||||

| A | B | C | D | |||||||||

| 2017 | Forestry | Canada | - | ✓ (A1–A3) | - | - | - | - | Literature | End-use product (SFH, MFH, multiuse building, flooring, furniture, decking) | [35] | |

| 2021 | Forestry | Ireland, Northern Ireland | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | - | - | Literature | - | [36] | |

| 2021 | Forestry | Finland | - | s. [23] | s. [23] | s. [23] | s. [23] | - | Literature | Functional unit groups (structural element, non-structural element, short-lived use) | [37] | |

| 2018 | Forestry | var. | var. | var. | var. | var. | var. | var. | var. | var. | [23] | |

| 2018 | Forestry and Construction | Japan | - | ✓ | - | - | - | 100 years | Literature | Functional equivalence for different products (equivalent soil improvement conditions, volume of sediment runoff, paving thickness, class for roadside earth-embedded guardrails or levels of sound transmission loss and wind load) | [38] | |

| 2020 | Construction | Global | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | - | - | Function: ceiling | [39] | |

| 2022 | Forestry | Global | - | ✓ (A1–A3) | - | - | - | 80 years | - | - | [40] | |

| 2018 | Construction | Quebec City, Canada | EN ISO 14067 EN ISO 14040 EN ISO 14044 | ✓ | - | - | - | - | Ecoinvent Database | Functional unit: 1 m2 of floor area for residential purposes | [41] | |

| OUTCOME | ||||||||||||

| Definition SP | SP | Substitution —Comparative Values | GHG Emission Reductions | Biogenic Carbon Storage | Reference | |||||||

| (ΣNfD * Kfp)/Dp | 0.54 tC/tC 0.45 tC/tC | Sawnwood —less wood-intensive products Panels —less wood-intensive products | - | - | [35] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood-GHGwood)/ (WUwood) | 1.85 tCO2e/tCO2e | Wood-based—alternative products | - | 0.9175 tCO2/m3 | [36] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood-GHGwood) /(WUwood-WUnon-wood) | Pine: 1.28 Mg C/Mg C Spruce: 1.16 Mg C/Mg C Birch: 1.43 Mg C/Mg C | Wood—non-wood | - | s. [37], Table 2 | [37] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood-GHGwood)/ (WUwood-WUnon-wood) | Ø 1.3 kgC/kgC (Structural construction); Ø 1.6 kgC/kgC (Non-structural construction) | Wood—non-wood | - | var. | [23] | |||||||

| - | 1.41 tCO2e/m3 | Wood—non-wood | s. [38], Table 1 | 1.04 tCO2e/m3 (incl. in SP) | [38] | |||||||

| - | - | CLT—RC | - | - | [39] | |||||||

| - | - | Engineered wood—conventional construction material | - | ✓ | [40] | |||||||

| - | - | EPS—cellulose Conventional floor materials —hardwood flooring system | 2.19 kg CO2e/m2 8.4 kg CO2e/m2 | ✓ | [41] | |||||||

| SCALING EFFECTS | ||||||||||||

| Scaling Level | Period/Date | Reference Scenario | Scenarios | Calculation Rules | GHG Emission Reductions | Biogenic Carbon Storage | Reference | |||||

| From the product level to the production level | 2019 | (0) Estimated production 2019 | - | Production volume [m3] * Carbon content [tCO2e/m3] * SP [tCO2/tCO2] | 1.09 Mt CO2e/year | - | [36] | |||||

| From the material level to the production and consumption levels | (0) 2015–2018 (a) - (b) 2030 (c) 2050 (d) 2003 (e) 2009 | (0) BAU | (a) Potential (b) WEM 2030 (c) WEM 2050 (d) Historical production 2003 (e) Historical production 2009 | Not evident * | (a) 1% (b) 9% (c) 32% (d) 20% (e) −30% | (0) 10.0 Tg CO2/year | [37] | |||||

| From the product/building level to the market level | By 2030 | (0) BAU | (a) Increase in sawnwood production by 1.8%/year (b) Increase in multi-storey residential wood buildings by 1% | Not evident * | (a) 88.7 Mt CO2e (b) 4.4 Mt CO2e | - | [23] | |||||

| From the product level to the production level | (1) By 2030 (2) By 2050 | (0) Zero scenario in 2017 | (a) Likely potential (b) Maximum potential | Production volume [m3] * SP [tCO2/m3] | (2a) 4.82 mio. tCO2e/year (2b) 9.63 mio. tCO2e/year | (1a) 1.09 mio. tCO2e/year (1b) 2.17 mio. tCO2e/year (2a) 2.18 mio. tCO2e/year (2b) 4.36 mio. tCO2e/year | [38] | |||||

| From the product (ceiling) level to the building market | 2020–2050 | (0) Baseline (S50) | Urban density scenarios: (a) Low (S25) (b) High (S75) Levels of uptake for hybrid systems: (A) u = 0 (no uptake) (B) u = 1 (full uptake) | s. [39], Equation (1) | (0A) 171–303 Mt CO2e (0B) 142–229 Mt CO2e (aA-B) and (bA-B) s. [39], Figure 5 (B) 22–82.8 Mt CO2e (GHG) | - | [39] | |||||

| From the product level to the building market | 2020–2100 | (0) BAU | Proportion of new urban population living in wooden buildings (a) 10% (b) 50% (c) 90% | Not evident * | (0) 138 Gt CO2 (a) 14 Gt CO2 lower, 10% lower (b) 71 Gt CO2 lower, 51% lower (c) 106 Gt CO2 lower, 77% lower | (a) 7 Gt CO2 (b) 33 Gt CO2 (c) 53 Gt CO2 | [40] | |||||

| From the product level to the building level | - | (0) Baseline | (a) EPS—cellulose (b) Conventional floor materials —hardwood flooring system | (emission reduction on product level)/(emission of the baseline building) | (a) 0.8% (b) 3.1% | - | [41] | |||||

| GENERAL CONDITIONS | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Sector Background of Authors | Scope of Application | Region | Standards | System Boundaries (Modules) | Reference Study Period | LCA Background Data and Database | Functional Units and Their Equivalence | Reference | |||

| A | B | C | D | |||||||||

| 2017 | Construction | Residential buildings | Germany; Austria | EN 15978, EN 15804, EN ISO 14040, EN ISO 14044, ISO/TS 14071, (EN 16485) | ✓ (A1–A3) | ✓ (B2 + B4) | ✓ (C3-C4) | - | 50 years | Ökobaudat | ✓ | [22] |

| 2020 | Forestry | Mixed-use buildings | Portland, USA | EN 15978, PAS 2050, ISO 14067 | ✓ | ✓ (B2, B4, (B6)) | ✓ | ✓ | 60 years | Athena LCI Database, U.S. LCI Database | ✓ | [42] |

| 2020 | Forestry | Mixed-use buildings and parking garages | var. | var. | ✓ (var.) | - | - | - | - | var. | - | [43] |

| 2022 | Construction | Non-residential buildings (office and administrative, agricultural, non-agricultural, other non-residential buildings) | Germany | EN 15978, EN 15804, EN ISO 14040, EN ISO 14044, ISO/TS 14071, (EN 16485) | ✓ | ✓ (B2 + B4) | ✓ | - | 50 years | Ökobaudat | ✓ | [21] |

| 2018 | Forestry | Mixed-use buildings | Ontario, Canada | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [44] |

| 2021 | Construction | Building superstructures | UK | EN 15978 | ✓ | ✓ (B1) | ✓ | ✓ | 50 years | Ecoinvent Database, Literature | ✓ | [45] |

| 2020 | Forestry | Residential buildings | South Africa | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | Literature | - | [46] |

| 2021 | Construction | Building | Kronoberg County, Sweden | - | ✓ | - | ✓ | ✓ (incl. in SP) | 80 years | - | - * | [47] |

| 2020 | Construction | Mixed-use buildings | Europe | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | - | - | [48] |

| 2019 | Construction | Residential buildings | Oslo, Norway | - | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ** | 50 years | Literature | ✓ | [49] |

| 2018 | Construction | Residential and commercial buildings | Melbourne, Australia; London, UK | - | ✓ | - | - | - | - | Literature | - | [50] |

| 2017 | Construction | Residential buildings | Harbin City, China | - | ✓ | ✓ (B6) | ✓ | ✓ ** | 50 years | - | - * | [51] |

| 2018 | Construction | Residential buildings | Sydney, Australia | - | ✓ (w/o A4) | ✓ (w/o B1, B6, B7) | ✓ (w/o C2) | - | 50 years | ICE Database GaBi Database, eTool | ✓ | [52] |

| 2019 | Construction | Parking garages | USA | - | ✓ (A1–A3) | - | - | - | - | ICE Database | - | [53] |

| 2018 | Construction and Forestry | Residential buildings | Germany | EN 15978, EN 15804, EN ISO 14040, EN ISO 14044, ISO/TS 14071, (EN 16485) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ ** | 50 years | Ökobaudat | ✓ | [54] |

| 2019 | Construction (Forestry) | Residential buildings | UK | BS EN 15804 | ✓ (A1–A3) | - | - | - | 100 years | EPDs | ✓ | [55] |

| 2019 | Forestry | Residential and non-residential buildings | China | - | ✓ (A1–A3) | - | - | - | - | Literature | ✓ | [56] |

| OUTCOME | ||||||||||||

| Definition of SP | SP | Substitution —Comparative Values | GHG Emission Reductions | Biogenic Carbon Storage | Reference | |||||||

| (GHGbuilding,mineral − GHGbuilding,timber) /(|GHGbuilding,minerals|) [kgCO2e/kgCO2e] | SFH/TFH 0.35–0.56 kgCO2e/m2 GEA MFH 0.09–0.48 kgCO2e/m2 GEA | Timber—mineral | SFH/TFH 77–207 kg CO2e/m2 35–56% MFH 18–178 kg CO2e/m2 9–48% | ✓ (considered in an −1/+1 approach according to EN 15978 and EN 15804) | [22] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood − GHGwood) /(WUwood) | −1.68 tCO2e/tCO2e | CLT—mineral | 3.51 × 106 kg CO2e (GHG emission) 70% (Embodied GHG emissions) | 1.84 × 106 kgCO2e (stored in CLT building) | [42] | |||||||

| - | - | CLT—RC | 216 kg CO2e/m2 of floor area 69% | var. | [43] | |||||||

| (GHGbuilding,mineral-GHGbuilding,timber) /(|GHGbuilding,minerals|) [kgCO2e/kgCO2e] | office and administrative buildings 0.06–0.48 kgCO2e/kgCO2e agricultural buildings 0.05–0.37 kgCO2e/kgCO2e non-agricultural buildings 0.14–0.44 kgCO2e/kgCO2e other non-residential buildings 0.13–0.46 kgCO2e/kgCO2e | Timber—mineral | Non-residential buildings 5–48% office and administrative buildings 17–177 kg CO2e/GEA 6–48% agricultural buildings 10–70 kg CO2e/GEA 5–37% non-agricultural buildings 10–170 kg CO2e/GEA 14–44% other non-residential buildings 37–133 kg CO2e/GEA 13–46% | ✓ (considered in an −1/+1 approach according to EN 15978 and EN 15804) | [21] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood-GHGwood) /(WUwood-WUnon-wood) | ø 8.91 tCO2e/tC in HWP | HWP —non-wood construction materials | - | - | [44] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood-GHGwood) /(WUwood-WUnon-wood) | 0.51 tC/tC 0.85 tC/tC | Timber—RC Timber—steel | Calculable from: timber 119 kgCO2e/m2; RC 185 kgCO2e/m2; steel 228 kgCO2e/m2 | 35.2 kg/m2 | [45] | |||||||

| - | - | - | - | - | [46] | |||||||

| - | - | Timber or CLT—RC | - | - | [47] | |||||||

| - | - | - | - | 1.84 kg CO2/kg wood; 23–310 CO2kg/m2 | [48] | |||||||

| - | - | Timber-based —RC | Calculable from [49], Table 4 (Production), 6 (Operation), 7 (End-of-Life) | - | [49] | |||||||

| - | - | Timber —concrete | Calculable from 523.6 kgCO2e/m2 (concrete building) and 508.8 kgCO2e/m2 (timber building) | - | [50] | |||||||

| - | - | CLT—RC | 13.2% Carbon emissions 9.9% energy consumption | 0.08 tCO2/m3 | [51] | |||||||

| - | - | Timber—brick | 10% LCE | - | [52] | |||||||

| - | - | Timber—precast concrete resp. cellular steel resp. post-tension concrete | Calculable from [53], Tables 7 and 8 | - | [53] | |||||||

| 0.35–0.56 kgCO2e/m2 GEA (SFH/TFH) 0.09–0.48 kgCO2e/m2 GEA (MFH) (according to [22]) | (GHGbuilding,mineral-GHGbuilding,timber)/(|GHGbuilding,minerals|) [kgCO2e/kgCO2e] (according to [22]) | Timber—mineral | 35–56% (SFH/TFH) 9–48% (MFH) (according to [22]) | - | [54] | |||||||

| - | - | Timber frame —masonry CLT—RC | 1.7–3.2 t CO2e 20% 12.8–18 t CO2e 60% | 2.0–4.2 t CO2e 12.4–17.3 t CO2e | [55] | |||||||

| (GHGnon-wood-GHGwood) /(WUwood-WUnon-wood) | 3.48 tC/tC | HWP —non-wood materials | s. [56], Table 1 | 1.84 kg CO2/kg HWP | [56] | |||||||

| SCALING EFFECTS | ||||||||||||

| Scaling Level | Period/Date | Reference Scenario | Scenarios | Calculation Rules | GHG Emission Reductions | Biogenic Carbon Storage | Reference | |||||

| From the building level to the building market | 2020–2030 | - | 50% of new constructions are wooden buildings | Total global annual emissions reductions = 50% of annual demand for new buildings *** annual emission reduction | 9% of annual emission reductions | - | [43] | |||||

| From the product level to the harvesting market | 100 years | (0) Baseline scenario | (1) Increased harvesting Production scenarios: (a) BAU (b) Lumber (c) Structural panel (d) Non-structural panel (e) Pulp and paper | GHGnet(t0 + t) = GHGHWP−inc(t0 + t) + ∆FC(t0 + t) | (a) 21 Mt CO2e (b) 93 Mt CO2e (c) 112 Mt CO2e (d) 66 Mt CO2e | (0) 1426 Mt C (1) 1373 Mt C | [44] | |||||

| From the building level to the building market | - | - | Comprehensive switch to engineered timber systems (apartments and commercial buildings); maximum potential | - | 1 MtCO2e/year 1.5% of emissions the construction sector can affect | - | [45] | |||||

| From the building level to the building market | - | - | Percentage of residential wood-based buildings: (a) 10%, (b) 20% (c) 100% | Not evident *** | (a) 2.4% (b) 4.9% (c) 30% | - | [46] | |||||

| From the building level to the harvesting market | 201 years | (0) BAU | (a) Production scenario (b) Set-aside scenario | Not evident *** | s. [47], Figures 8, 10, 12, 14 and 16 | - | [47] | |||||

| From the building level to the buildings market | 2020–2040 | - | Percentage of wooden buildings: (a) 5%, (b) 10% (c) 45%, (d) 80% | Not evident *** | - | 1–55 Mt CO2/year; 0.022–1.067 Gt CO2 | [48] | |||||

| From the building level to the building market | 2015–2030 | (0) REF | (a) ‘55/15′ | s. [15,24] | 0.8 Mt CO2e/year | (0) −0.96 Mt CO2/year (a) Δ −0.65 Mt CO2/year | [54] | |||||

| From the building level to the building market | 2050 | (0) No growth (2018; refers to the level of timber construction activity) | Rates of house-building activity: (a) Low and (b) high levels of timber construction activity: (A) BAU (B) Moderate growth (C) High growth | Not evident *** | Residential buildings (a) [55], Table E6 (b) [55], Table E7 Non-residential buildings [55], Table E14 | Residential buildings (a) [55], Table E6 (b) [55], Table E7 Non-residential buildings [55], Table E14 | [55] | |||||

| (1) From the product level to the consumption level (2) From the building level to the building market | (1) 2014 (2) 2015 | (01) National HWP consumption of 2014 (02) Total gross floor area in 2015 | (1a) +10% HWP + substitution of non-wood materials in construction and furniture production (1b) +10% HWP + substitution of non-wood construction materials (2a) 10% wood-frame construction of total gross floor area (2b) Additional HWP substitute GHG-intensive construction materials | Not evident *** | (1a) 18.76 Mt C (1b) 22.5 Mt C (2a) 8.11 Mt C (2b) 28.22 Mt C | - | [56] | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piayda, C.; Hafner, A.; Rüter, S. A Review of Current Substitution Estimates for Buildings with Regard to the Impact on Their GHG Balance and Correlated Effects—A Systematic Comparison. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198593

Piayda C, Hafner A, Rüter S. A Review of Current Substitution Estimates for Buildings with Regard to the Impact on Their GHG Balance and Correlated Effects—A Systematic Comparison. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198593

Chicago/Turabian StylePiayda, Charlotte, Annette Hafner, and Sebastian Rüter. 2025. "A Review of Current Substitution Estimates for Buildings with Regard to the Impact on Their GHG Balance and Correlated Effects—A Systematic Comparison" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198593

APA StylePiayda, C., Hafner, A., & Rüter, S. (2025). A Review of Current Substitution Estimates for Buildings with Regard to the Impact on Their GHG Balance and Correlated Effects—A Systematic Comparison. Sustainability, 17(19), 8593. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198593