Towards More Nuanced Narratives in Bioeconomy Strategies and Policy Documents to Support Knowledge-Driven Sustainability Transitions

Abstract

1. Introduction: Revisiting the Bioeconomy Communication Challenge

- A biotechnology vision (e.g., striving for new biotechnological research, application, and commercialisation);

- A bioresource vision (e.g., striving for upgrading and conversion of natural resources and new value chains through research, development, and demonstration, also driven by biotechnology); and

- A bioecology vision (e.g., striving for circular processes and considering ecosystems and society).

- Bioeconomy communication challenge: The narrative focus of current bioeconomy (policy) communication has side-lined social inclusion, considerations of justice and responsibility, stakeholder dialogue, and participation as well as other forms of (social and transformative) innovation beyond new technologies (e.g., [2,35,49]).

- Competing bioeconomy visions: There is no consensus on what the term ‘bioeconomy’ means (e.g., [21,22,23,24,25,26]). This can create various conflicts between narratives, visions, and interests of bioeconomy stakeholders, potentially undermining effective communication and (transdisciplinary) collaboration.

- Bias towards technological fixes: Policies and strategies often continue to focus on techno-economic frameworks and solutions. This means they pay insufficient attention to the complexity of the normative dimensions of transformations towards sustainability. This results in an inadequate focus on processes and platforms that facilitate participation, stakeholder dialogue, and inclusion. These processes and platforms should also facilitate the exnovation and phase-out of unsustainable and unjust structures and practices (and the corresponding narratives) (e.g., [2,8,9,49,50]).

- Developing more nuanced (understandings of) bioeconomy narratives: Narrative approaches can offer ways of translating abstract concepts into meaningful and comprehensible stories, thus connecting political visions with lived experiences. We thus call for greater recognition and a more nuanced treatment of narratives at the intersection of bioeconomy policy, science, and communication.

2. The Power of Narratives Is Key for Science Communication in General and Bioeconomy Communication in Particular

3. Bridging the Gap Between Research and Policy-Making with Narrative Contributions to Bioeconomy Strategies

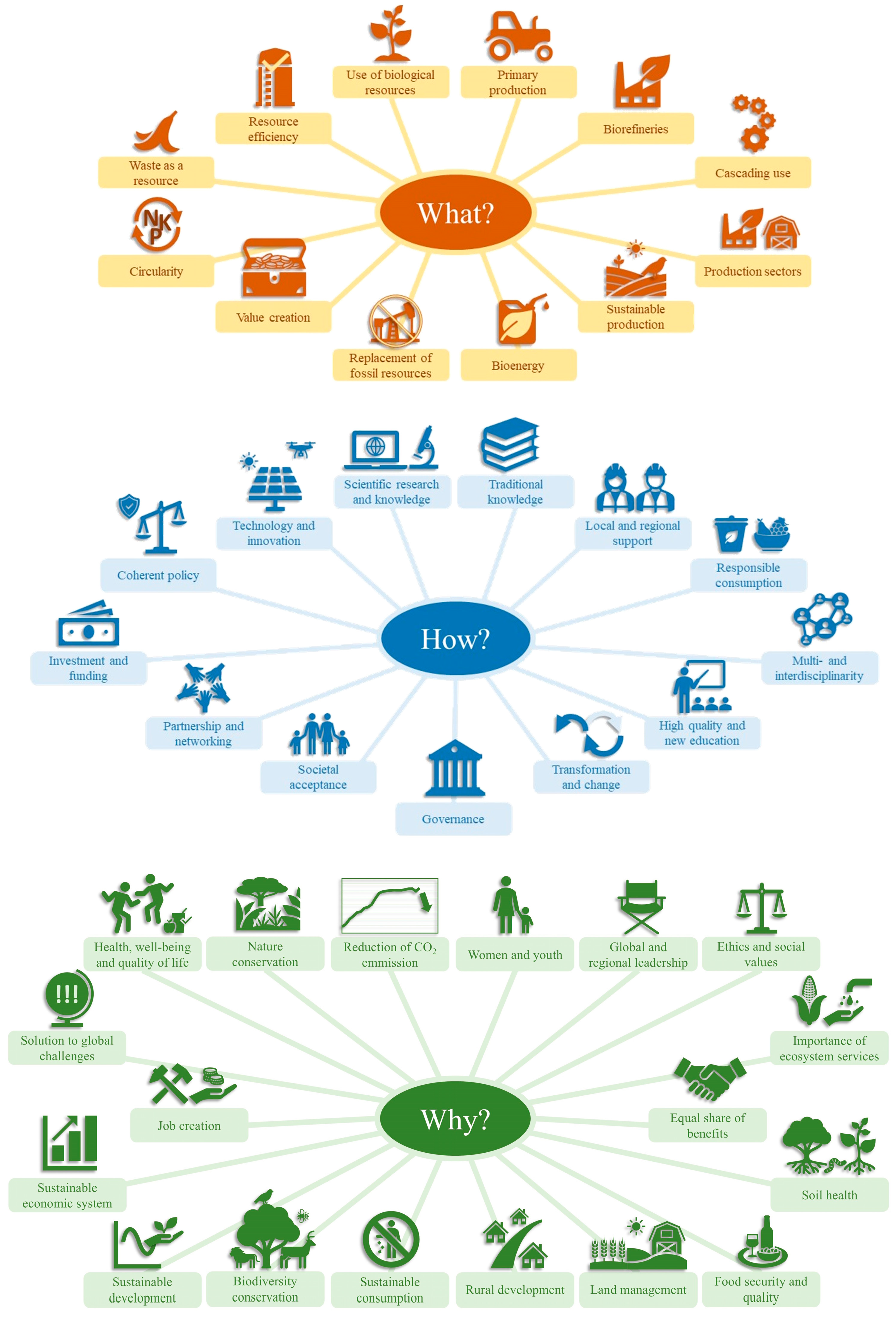

4. What? How? Why? Navigating Narrative Diversity Through ‘Boundary Objects’

5. So What? Concluding Remarks and Implications

- The attractiveness, selection, and persuasive impact of narratives have been found to be strongly connected to emotions (e.g., [73,107]), which have also been argued to play a key role in sustainability transitions (e.g., [108]), not least when actors are faced with (often inevitable) phase-outs and “transition pain” [109]. We thus call for research focusing on the interplay between emotions, bioeconomy narratives, and the creative and destructive (e.g., innovation vs. exnovation) sides of sustainability transitions.

- Given the methodological challenges of assessing the impact of narratives on policy outcomes, focussing on narrative elements may not offer unambiguous ways of capturing how narratives lead to actual policy changes or shifts in public opinion, which complicates efforts to monitor and evaluate narrative approaches and interventions [95]. Further research is needed, therefore, to improve policy monitoring and evaluation of narrative approaches in bioeconomy strategies and policy documents.

- As the bioeconomy is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary endeavour, problematic epistemic hierarchies and lock-in into the ‘monocultures’ of a single discipline can hinder the collaboration necessary for co-creating bioeconomy narratives. Scientists often struggle to communicate effectively not just with policy-makers or ‘laypeople’ but even with other scholars (especially those outside their own field or discipline), which creates challenges for the co-creation and integration of knowledge [110] as well as the societal uptake of narratives. Consequently, there is a need for investigations into successful institutional reforms that can better support and incentivise transdisciplinary research in sustainability and the bioeconomy.

- As highlighted by various authors, successful bioeconomy transitions require public understanding and engagement, professional support through intermediaries, awareness of a shared responsibility, and a common dedication and purpose, as technological promises and economic incentives alone will be insufficient and potentially unsustainable (e.g., [49,83,111]). Therefore, narratives are no panacea for sustainability transitions, and narrative approaches to bioeconomy policy will always be interdependent with the diversity of stakeholders’ perspectives and opinions, political preferences and ideologies, media interpretations, current research data, and societal as well as economic incentives, to name but a few. Therefore, investigating the interplay between public opinion dynamics, voting behaviour, and the legitimacy and adoption of bioeconomy policies and strategies represents another relevant avenue for future work. Here, it would be equally important to examine whether and to what extent there are narrative patterns among societal groups and other stakeholders, and how subsidies, dedicated funding schemes, and regulatory incentives influence the prevalence and diffusion of such narrative patterns.

- Accordingly, policy-makers should strive for narrative frameworks that are sensitive to the complexity of sensemaking and the normative dimensions of transformations, also taking into account potential lock-ins and counter-narratives emerging from dominant (e.g., neoliberal) economic paradigms and discourses (e.g., [19,89,90]). This calls for establishing more dedicated platforms for participation and co-creation with citizens and other stakeholders, fostering bottom–up processes and communication among the different stakeholder groups that share responsibility and agency for sustainability transitions. Acknowledging and facilitating consumer responsibility is just one example here (e.g., [16,17,87]). The details of how such platforms can and should be designed and operated remain a task for future work.

- It is evident that those in positions of authority and power, such as policy-makers, can use narratives to influence attitudes and behaviours by employing emotional engagement and storytelling techniques (see also the first bullet point on emotions). In line with the notion of narrative literacy and reflexivity discussed above, we therefore call for the use of nuanced, inclusive, and participatory narratives in bioeconomy policies and strategies that do not perpetuate existing inequalities and power relations.

- The media shares a significant part of the responsibility for framing public policy issues, influencing public perception and discourse. Thus, they also take part in shaping collective sensemaking and amplifying narratives and counter-narratives regarding (the translation of) bioeconomy policies. At the same time, the media can hold policy-makers, industry, and science accountable (e.g., [41,42]). This underscores the importance of ‘narrative literacy’ as part of the shared responsibility in bioeconomy transitions. We thus appeal to the media to take their responsibility for co-creating and disseminating inclusive, participatory, and critical narratives seriously to help overcome the bioeconomy communication challenges discussed above.

- Bioeconomy narratives may serve as ‘boundary objects’ that facilitate communication and coordination between diverse stakeholder groups such as policy-makers, scientists, industry, and society. Such boundary objects (e.g., framed around what, how, and why questions) may allow various groups to align their objectives while maintaining their distinct perspectives and diverse interpretations (see [103,104]). We thus encourage more engagement with the idea of boundary objects in the bioeconomy, being particularly mindful about how power relations influence the directionality of bioeconomy transitions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bugge, M.M.; Hansen, T.; Klitkou, A. What Is the Bioeconomy? A Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2016, 8, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eversberg, D.; Koch, P.; Lehmann, R.; Saltelli, A.; Ramcilovic-Suominen, S.; Kovacic, Z. The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same: Promises of Bioeconomy and the Economy of Promises. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lühmann, M.; Vogelpohl, T. The Bioeconomy in Germany: A Failing Political Project? Ecol. Econ. 2023, 207, 107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurca, A. Why Is Communicating the Circular Bioeconomy so Challenging? Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2023, 3, 1223–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabbert, S.; Lewandowski, I.; Weiss, J.; Pyka, A. (Eds.) Knowledge-Driven Developments in the Bioeconomy: Technological and Economic Perspectives; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; ISBN 978-3-319-58373-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pyka, A.; Prettner, K. Economic Growth, Development, and Innovation: The Transformation towards a Knowledge-Based Bioeconomy. In Bioeconomy—Shaping the Transition to a Sustainable, Biobased Economy; Lewandowski, I., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 331–340. ISBN 978-3-319-68152-1. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, I.; Grundel, I. Regional Policy Mobilities: Shaping and Reshaping Bioeconomy Policies in Värmland and Västerbotten, Sweden. Geoforum 2021, 121, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmetzer, S.; Schlaile, M.P.; Bogner, K.; Mueller, M.; Pyka, A. Exploring the Dedicated Knowledge Base of a Transformation towards a Sustainable Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, K.; Dahlke, J. Born to Transform? German Bioeconomy Policy and Research Projects for Transformations towards Sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 195, 107366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmetzer, S.; Lask, J.; Vargas-Carpintero, R.; Pyka, A. Learning to Change: Transformative Knowledge for Building a Sustainable Bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 167, 106435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmetzer, S.; Mayorga, L.; Lask, J.; Winkler, B.; Reinmuth, E.; Lewandowski, I. Education and Awareness in the Bioeconomy. In Handbook on the Bioeconomy; Viaggi, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 301–331. ISBN 978-1-80037-349-5. [Google Scholar]

- Pubule, J.; Blumberga, A.; Rozakis, S.; Vecina, A.; Kalnbalkite, A.; Blumberga, D. Education for Advancing the Implementation of the Bioeconomy Goals: An Analysis of Master Study Programmes in Bioeconomy. Environ. Clim. Technol. 2020, 24, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, A.; de Olde, E.M.; Ripoll-Bosch, R.; Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Metze, T.A.P.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; van Ittersum, M.K.; de Boer, I.J.M. Principles, Drivers and Opportunities of a Circular Bioeconomy. Nat. Food 2021, 2, 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F.X.; Canales, N.; Fielding, M.; Gladkykh, G.; Aung, M.T.; Bailis, R.; Ogeya, M.; Olsson, O. A Comparative Analysis of Bioeconomy Visions and Pathways Based on Stakeholder Dialogues in Colombia, Rwanda, Sweden, and Thailand. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2022, 24, 680–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Kask, J.; Brewer, J.; Bogner, K.; Urmetzer, S.; De Witt, A. Proposing a Cultural Evolutionary Perspective for Dedicated Innovation Systems: Bioeconomy Transitions and Beyond. J. Innov. Econ. Manag. 2022, 38, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilke, U.; Schlaile, M.P.; Urmetzer, S.; Mueller, M.; Bogner, K.; Pyka, A. Time to Say ‘Good Buy’ to the Passive Consumer? A Conceptual Review of the Consumer in the Bioeconomy. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2021, 34, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, S.; Minnucci, G.; Mueller, M.; Schlaile, M.P. The Role of Consumers in Business Model Innovations for a Sustainable Circular Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hector, V.; Friedrich, J.; Schlaile, M.P.; Panagiotou, A.; Bieling, C. From Farm to Table: Uncovering Narratives of Agency and Responsibility for Change among Actors along Agri-Food Value Chains in Germany. Agric. Hum. Values 2025, 42, 1805–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivien, F.-D.; Nieddu, M.; Befort, N.; Debref, R.; Giampietro, M. The Hijacking of the Bioeconomy. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 159, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinderer, S.; Brändle, L.; Kuckertz, A. Transition to a Sustainable Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biber-Freudenberger, L.; Ergeneman, C.; Förster, J.J.; Dietz, T.; Börner, J. Bioeconomy Futures: Expectation Patterns of Scientists and Practitioners on the Sustainability of Bio-Based Transformation. Sustain. Dev. 2020, 28, 1220–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausknost, D.; Schriefl, E.; Lauk, C.; Kalt, G. A Transition to Which Bioeconomy? An Exploration of Diverging Techno-Political Choices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieken, S.; Dallendörfer, M.; Henseleit, M.; Siekmann, F.; Venghaus, S. The Multitudes of Bioeconomies: A Systematic Review of Stakeholders’ Bioeconomy Perceptions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 1703–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Najork, K.; Keck, M.; Zscheischler, J. Bioeconomic Fiction between Narrative Dynamics and a Fixed Imaginary: Evidence from India and Germany. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, J.; Zscheischler, J.; Faust, H. Preservation, Modernization, and Transformation: Contesting Bioeconomic Imaginations of “Manure Futures” and Trajectories toward a Sustainable Livestock System. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Friedrich, J.; Porst, L.; Zscheischler, J. Bioeconomy Innovations and Their Regional Embeddedness: Results from a Qualitative Multiple-Case Study on German Flagship Innovations. Progress. Econ. Geogr. 2025, 3, 100044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, M.E. The Bioeconomy: A Primer; Congressional Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Giampietro, M.; Funtowicz, S.; Bukkens, S.G.F. Thou Shalt Not Take the Name of Bioeconomy in Vain. Sustain. Sci. 2025, 20, 725–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeali, W.; Schlaile, M.P.; Winkler, B. Navigating the Biocosmos: Cornerstones of a Bioeconomic Utopia. Land. 2023, 12, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormick, K.; Kautto, N. The Bioeconomy in Europe: An Overview. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2589–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Bioeconomy Strategy. Available online: https://environment.ec.europa.eu/strategy/bioeconomy-strategy_en (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- European Commission. A Sustainable Bioeconomy for Europe: Strengthening the Connection Between Economy, Society and the Environment: Updated Bioeconomy Strategy; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. European Bioeconomy Policy: Stocktaking and Future Developments; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zepharovich, E.; Völker, T.; Kovacic, Z.; Serrano, Y. Bioeconomy Narratives. In EU Biomass Supply, Uses, Governance and Regenerative Actions: 10 Year Anniversary Edition; European Commission, Joint Research Centre (JRC), Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025; pp. 44–49. [Google Scholar]

- Proestou, M.; Schulz, N.; Feindt, P.H. A Global Analysis of Bioeconomy Visions in Governmental Bioeconomy Strategies. Ambio 2024, 53, 376–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgescu-Roegen, N. The Promethean Condition of Viable Technologies. Mater. Soc. 1983, 7, 425–435. [Google Scholar]

- International Advisory Council on Global Bioeconomy. Global Bioeconomy Policy Report (IV): A Decade of Bioeconomy Policy Development around the World; Secretariat of the Global Bioeconomy Summit 2020: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://gbs2020.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/GBS-2020_Global-Bioeconomy-Policy-Report_IV_web-2.pdf (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- BIOCOM Worldwide Strategies|Bioökonomie.de. Available online: https://biooekonomie.de/en/topics/in-depth-reports-worldwide (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Dallendörfer, M.; Dieken, S.; Henseleit, M.; Siekmann, F.; Venghaus, S. Investigating Citizens’ Perceptions of the Bioeconomy in Germany—High Support but Little Understanding. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 30, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, J.P.; Murphy, E.; Scott, M. Downscaling EU Bioeconomy Policy for National Implementation. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2024, 9, 100121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurston, W.E.; Rutherford, E.; Meadows, L.M.; Vollman, A.R. The Role of the Media in Public Participation: Framing and Leading? Women Health 2005, 41, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltomaa, J. Drumming the Barrels of Hope? Bioeconomy Narratives in the Media. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoori, A.P. Between Narrative and Reception: Towards a Cultural/Contextualist Model of Foreign Policy Reporting and Public Opinion Formation. J. Int. Commun. 1997, 4, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanfiel, M.T.S.; Igartua, J.J. Cultural Proximity and Interactivity in the Processes of Narrative Reception. Int. J. Arts Technol. 2016, 9, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renner, A.; Giuntoli, J.; Barredo Cano, J.I.; Ceddia, M.; Guimarães Pereira, Â.; Paracchini, M.L.; Quagila, A.P.; Trombetti, M.; Vallercillo, S.; Velasco Gomez, M.; et al. Integrated Assessment of Bioeconomy Sustainability—Principles and Methods of an Accounting System Based on Societal Metabolism; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Abatecola, G.; Allard-Poesi, F.; Ataci, T.; Cristofaro, M.; Kosch, O.; Lee, B.; Schlaile, M.P.; Secchi, D.; Szarucki, M.; Xian, H. Interactive Reflexivity: A Means to Addressing Methodological Challenges in International Research in Management. Manag. Decis. 2025, 63, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvesson, M.; Sköldberg, K. Reflexive Methodology: New Vistas for Qualitative Research, 3rd ed.; SAGE: London, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-4739-6424-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Axsen, J.; Sorrell, S. Promoting Novelty, Rigor, and Style in Energy Social Science: Towards Codes of Practice for Appropriate Methods and Research Design. Energy Res. Social. Sci. 2018, 45, 12–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Friedrich, J.; Zscheischler, J. Rethinking Regional Embeddedness and Innovation Systems for Transitions Towards Just, Responsible, and Circular Bioeconomies. J. Circ. Econ. 2024, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlaile, M.P.; Urmetzer, S.; Blok, V.; Andersen, A.D.; Timmermans, J.; Mueller, M.; Fagerberg, J.; Pyka, A. Innovation Systems for Transformations towards Sustainability? Taking the Normative Dimension Seriously. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagraa, B. Homo Narrans and the Science of the Word: Toward a Caribbean Radical Imagination. Crit. Ethn. Stud. 2018, 4, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, L. Narrative and Sociology. J. Contemp. Ethnogr. 1990, 19, 116–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBeth, M.K.; Shanahan, E.A.; Hathaway, P.L.; Tigert, L.E.; Sampson, L.J. Buffalo Tales: Interest Group Policy Stories in Greater Yellowstone. Policy Sci. 2010, 43, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudrum, D. From Narrative Representation to Narrative Use: Towards the Limits of Definition. Narrative 2005, 13, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downs, J.S. Prescriptive Scientific Narratives for Communicating Usable Science. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13627–13633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadlallah, R.; El-Jardali, F.; Nomier, M.; Hemadi, N.; Arif, K.; Langlois, E.V.; Akl, E.A. Using Narratives to Impact Health Policy-Making: A Systematic Review. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2019, 17, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedy, C. Discourse Coalitions for Sustainability Transformations: Common Ground and Conflict beyond Neoliberalism. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 45, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viehöver, W. Diskurse als Narrationen. In Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Diskursanalyse. Band I: Theorien und Methoden; Keller, R., Hirseland, A., Schneider, W., Viehöver, W., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2001; pp. 177–206. [Google Scholar]

- Abell, P. Narrative Explanation: An Alternative to Variable-Centered Explanation? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2004, 30, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, M.F. Using Narratives and Storytelling to Communicate Science with Nonexpert Audiences. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13614–13620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, H. Narrative der Sozial-Ökologischen Transformation der Wirtschaft am Beispiel der Ernährungswirtschaft; Metropolis-Verlag: Marburg, Germany, 2024; ISBN 978-3-7316-1572-9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K. A Narrative Policy Framework: Clear Enough to Be Wrong? Policy Stud. J. 2010, 38, 329–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, D.A. Policy Paradox: The Art of Political Decision Making, 3rd ed.; Norton: New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-393-91272-2. [Google Scholar]

- Dobroć, P.; Bögel, P.; Upham, P. Narratives of Change: Strategies for Inclusivity in Shaping Socio-Technical Future Visions. Futures 2023, 145, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendelsohn, E. The Social Construction of Scientific Knowledge. In The Social Production of Scientific Knowledge; Mendelsohn, E., Weingart, P., Whitley, R.D., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1977; pp. 3–26. ISBN 978-90-277-0776-5. [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky, A.J.; Kinder, D.R. Making Sense of Issues Through Media Frames: Understanding the Kosovo Crisis. J. Politics 2006, 68, 640–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K.; Shanahan, E.A. Chapter 1: A Brief Introduction to the Narrative Policy Framework. In Narratives and the Policy Process: Applications of the Narrative Policy Framework; Jones, M.D., McBeth, M.K., Shanahan, E.A., Eds.; Montana State University Library: Bozeman, Montana, 2022; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, J. The Power of Narrative to Enhance Quality in Teaching, Learning, and Research. In Learning and Teaching for the Twenty-First Century: Festschrift for Professor Phillip Hughes; Maclean, R., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 17–33. ISBN 978-1-4020-5773-1. [Google Scholar]

- Caracciolo, M. Narrative, Meaning, Interpretation: An Enactivist Approach. Phenom. Cogn. Sci. 2012, 11, 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, M.; Klein, O. (Re) Territorialising Policy Narratives and Their Role for Novel Bioeconomy Sectors in the EU. In Rescaling Sustainability Transitions; Halonen, M., Albrecht, M., Kuhmonen, I., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 17–41. ISBN 978-3-031-69917-7. [Google Scholar]

- Görmar, F. Weaving a Foundational Narrative—Place-Making and Change in an Old-Industrial Town in East Germany. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2024, 32, 2338–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, L.M. Between Climates of Fear and Blind Optimism: The Affective Role of Emotions for Climate (In)Action. Geogr. Helv. 2022, 77, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, R.L.; Green, M.C. The Role of a Narrative’s Emotional Flow in Promoting Persuasive Outcomes. Media Psychol. 2015, 18, 137–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddi, M.; Kuo, R.; Kreiss, D. Identity Propaganda: Racial Narratives and Disinformation. New Media Soc. 2023, 25, 2201–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehling, E. Politisches Framing: Wie Eine Nation Sich Ihr Denken einredet—Und Daraus Politik Macht; Edition Medienpraxis; Herbert von Halem Verlag: Köln, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-86962-208-8. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, S.P.; Guilbert, S.M.; Smith, M.L.; Hakimelahi, S.; Phillips, L.M. A Theoretical Framework for Narrative Explanation in Science. Sci. Educ. 2005, 89, 535–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrom, M.; Ritland, R. The Problem of Communicating Beyond Human Scale. In Between Scientists & Citizens: Proceedings of a Conference at Iowa State University, 1–2 June 2012; Goodwin, J., Ed.; Great Plains Society for the Study of Argumentation: Ames, IA, USA, 2012; pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Y. Against Storytelling of Scientific Results. Nat. Methods 2013, 10, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M.C.; Rossiter, M. Narrative Learning in Adulthood. New Dir. Adult Contin. Educ. 2008, 2008, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avraamidou, L.; Osborne, J. The Role of Narrative in Communicating Science. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2009, 31, 1683–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoens, M.C.; Fuenfschilling, L.; Leipold, S. Discursive Dynamics and Lock-Ins in Socio-Technical Systems: An Overview and a Way Forward. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 1841–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urmetzer, S.; Pyka, A. Varieties of Knowledge-Based Bioeconomies. In Knowledge-Driven Developments in the Bioeconomy; Dabbert, S., Lewandowski, I., Weiss, J., Pyka, A., Eds.; Economic Complexity and Evolution; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 57–82. ISBN 978-3-319-58373-0. [Google Scholar]

- Viaggi, D. The Bioeconomy: Delivering Sustainable Green Growth; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Majone, G. Evidence, Argument and Persuasion in the Policy Process; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 1989; ISBN 978-0-300-05259-6. [Google Scholar]

- Crow, D.; Jones, M. Narratives as Tools for Influencing Policy Change. Policy Politics 2018, 46, 217–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkoreit, M. Mindmade Politics: The Cognitive Roots of International Climate Governance; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-0-262-03630-6. [Google Scholar]

- Wensing, J.; Bearth, A.; Caputo, V. Consumer Adoption of Bioeconomy Products. In Handbook on the Bioeconomy; Viaggi, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 82–102. ISBN 978-1-80037-349-5. [Google Scholar]

- Luederitz, C.; Abson, D.J.; Audet, R.; Lang, D.J. Many Pathways toward Sustainability: Not Conflict but Co-Learning between Transition Narratives. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D. Sustainability Narratives as Transformative Solution Pathways: Zooming in on the Circular Economy. Circ. Econ. Sust. 2021, 1, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedy, C.; Waddock, S. Imagining Transformation: Change Agent Narratives of Sustainable Futures. Futures 2022, 142, 103010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallahan, K. Strategic Framing. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication; Donsbach, W., Ed.; Wiley: Singapore, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4051-3199-5. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert, S. Varieties of Framing the Circular Economy and the Bioeconomy: Unpacking Business Interests in European Policymaking. J. Environ. Policy Plan. 2021, 23, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, E.A.; Jones, M.D.; McBeth, M.K. Policy Narratives and Policy Processes. Policy Stud. J. 2011, 39, 535–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowndes, V. Storytelling and Narrative in Policymaking. In Evidence-Based Policy Making in the Social Sciences: Methods that Matter; Stoker, G., Evans, M., Eds.; Policy Press: Bristol, UK, 2016; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, E.A.; DeLeo, R.; Koebele, E.A.; Taylor, K.; Crow, D.A.; Blanch-Hartigan, D.; Albright, E.A.; Birkland, T.A.; Minkowitz, H. Narrative Power in the Narrative Policy Framework. Policy Stud. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.T.; Larson, J.C.; Buckingham, S.L.; Maton, K.I.; Crowley, D.M. Bridging the Research–Policy Divide: Pathways to Engagement and Skill Development. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry 2019, 89, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, D.; Farina, C.R.; Heidt, J. The Value of Words: Narrative as Evidence in Policy Making. Evid. Policy 2014, 10, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haraway, D. Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. Fem. Stud. 1988, 14, 575–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priefer, C.; Meyer, R. One Concept, Many Opinions: How Scientists in Germany Think About the Concept of Bioeconomy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciplet, D.; Harrison, J.L. Transition Tensions: Mapping Conflicts in Movements for a Just and Sustainable Transition. Environ. Politics 2020, 29, 435–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graaff, S.; Wanzenböck, I.; Frenken, K. The Politics of Directionality in Innovation Policy through the Lens of Policy Process Frameworks. Sci. Public. Policy 2025, 52, 418–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittmayer, J.M.; Backhaus, J.; Avelino, F.; Pel, B.; Strasser, T.; Kunze, I.; Zuijderwijk, L. Narratives of Change: How Social Innovation Initiatives Construct Societal Transformation. Futures 2019, 112, 102433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, M.J.; Wesseling, J.; Torrens, J.; Weber, K.M.; Penna, C.; Klerkx, L. Missions as Boundary Objects for Transformative Change: Understanding Coordination across Policy, Research, and Stakeholder Communities. Sci. Public Policy 2023, 50, 398–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco-Torres, M.; Rogers, B.C.; Ugarelli, R.M. A Framework to Explain the Role of Boundary Objects in Sustainability Transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2020, 36, 34–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinmuth, E.; Zwack, S.G. Definition and Narratives of Bioeconomy. BioBeo Project Working Paper (V-13.01.2023). Zenodo 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, J.E. If This Is Your Land, Where Are Your Stories? In Finding Common Ground; A.A. Knopf Canada: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2003; ISBN 978-0-676-97491-1. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, S.R.; Halpern, M.; Horst, M.; Kirby, D.; Lewenstein, B. Science Stories as Culture: Experience, Identity, Narrative and Emotion in Public Communication of Science. J. Sci. Commun. 2019, 18, A01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höhle, J.; Van Poeck, K. Studying Feelings in Action: An Analytical Framework for Empirical Analyses of Affect in Sustainability Transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2025, 57, 101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, K.; Kump, B.; Beekman, M.; Wittmayer, J. Coping with Transition Pain: An Emotions Perspective on Phase-Outs in Sustainability Transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2024, 50, 100806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, R.W.; Zscheischler, J.; Köckler, H.; Czichos, R.; Hofmann, K.-M.; Sindermann, C. Transdisciplinary Knowledge Integration—PART I: Theoretical Foundations and an Organizational Structure. Technol. Forecast. Social. Change 2024, 202, 123281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, A.; Lang, S.; Ari, E. What Can the Bioeconomy Contribute to the Achievement of Higher Degrees of Sustainability? From Substitution to Structural Change to Transformation. In Handbook on the Bioeconomy; Viaggi, D., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2025; pp. 197–215. ISBN 978-1-80037-349-5. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stoye, J.; Schlaile, M.P.; von Cossel, M.; Bertacchi, S.; Escórcio, R.; Winkler, B.; Curran, T.P.; Ní Chléirigh, L.; Nic an Bhaird, M.; Klakla, J.B.; et al. Towards More Nuanced Narratives in Bioeconomy Strategies and Policy Documents to Support Knowledge-Driven Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198590

Stoye J, Schlaile MP, von Cossel M, Bertacchi S, Escórcio R, Winkler B, Curran TP, Ní Chléirigh L, Nic an Bhaird M, Klakla JB, et al. Towards More Nuanced Narratives in Bioeconomy Strategies and Policy Documents to Support Knowledge-Driven Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198590

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoye, Juliane, Michael P. Schlaile, Moritz von Cossel, Stefano Bertacchi, Rita Escórcio, Bastian Winkler, Thomas P. Curran, Laoise Ní Chléirigh, Máire Nic an Bhaird, Jan Bazyli Klakla, and et al. 2025. "Towards More Nuanced Narratives in Bioeconomy Strategies and Policy Documents to Support Knowledge-Driven Sustainability Transitions" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198590

APA StyleStoye, J., Schlaile, M. P., von Cossel, M., Bertacchi, S., Escórcio, R., Winkler, B., Curran, T. P., Ní Chléirigh, L., Nic an Bhaird, M., Klakla, J. B., Nachtergaele, P., Ciantar, H., Scheurich, P., Lewandowski, I., & Reinmuth, E. (2025). Towards More Nuanced Narratives in Bioeconomy Strategies and Policy Documents to Support Knowledge-Driven Sustainability Transitions. Sustainability, 17(19), 8590. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198590