The Evolution of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance: A Longitudinal Comparative Study on Moderators of Agenda 2030

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

2.1. The Quest for Sustainable Economic Development

2.2. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and the Policy Perspective

2.3. ESG and Its Role in Sustainability

2.4. The Impact of ESG on Corporate Performance

2.5. Explaining Social Pillar Challenges via Stakeholder and Institutional Theories

2.6. Bridging the Gap: Empirical Evidence on ESG, SDGs, and Corporate Performance

3. Data and Methods

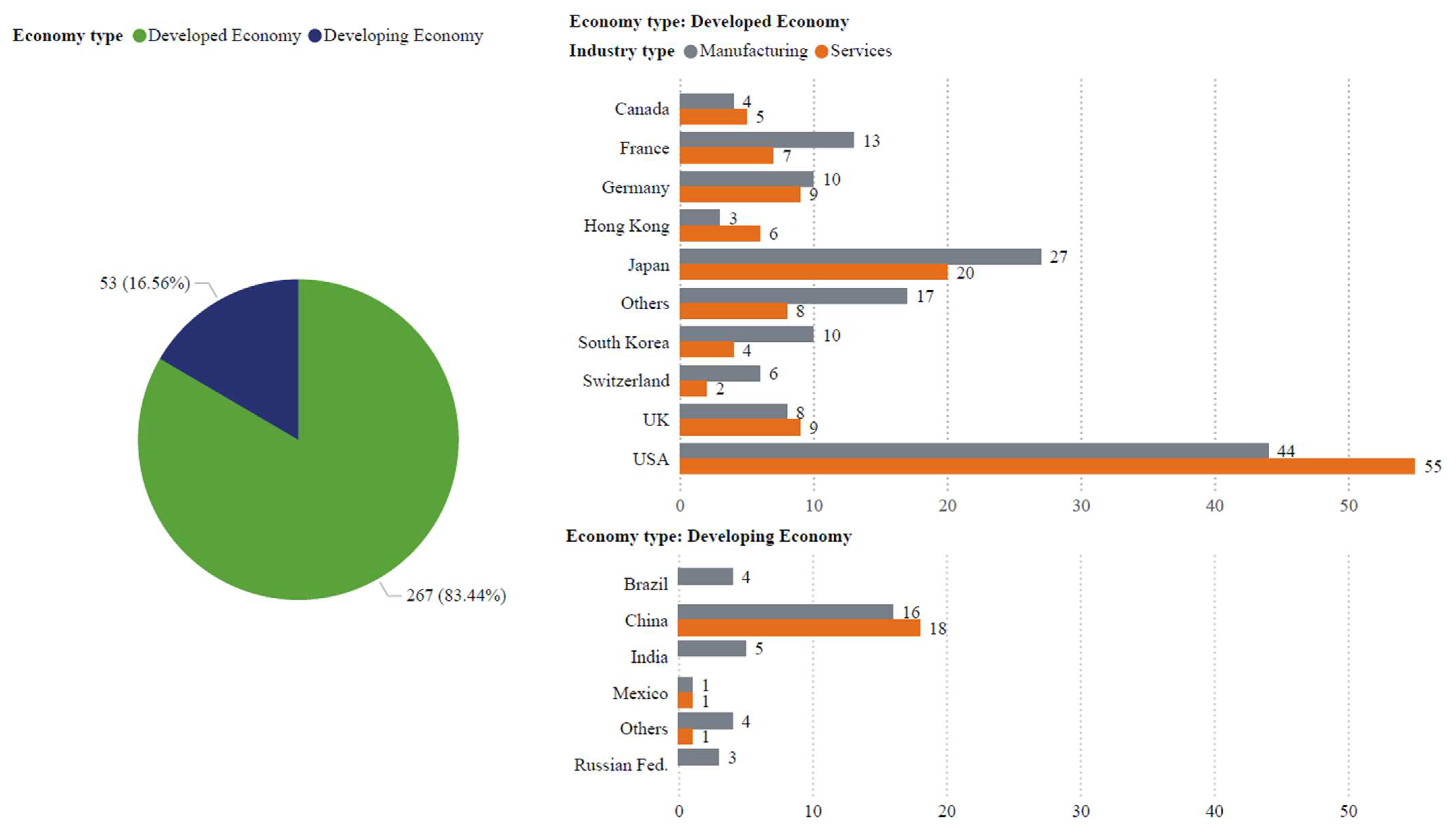

3.1. Data

3.2. Methods

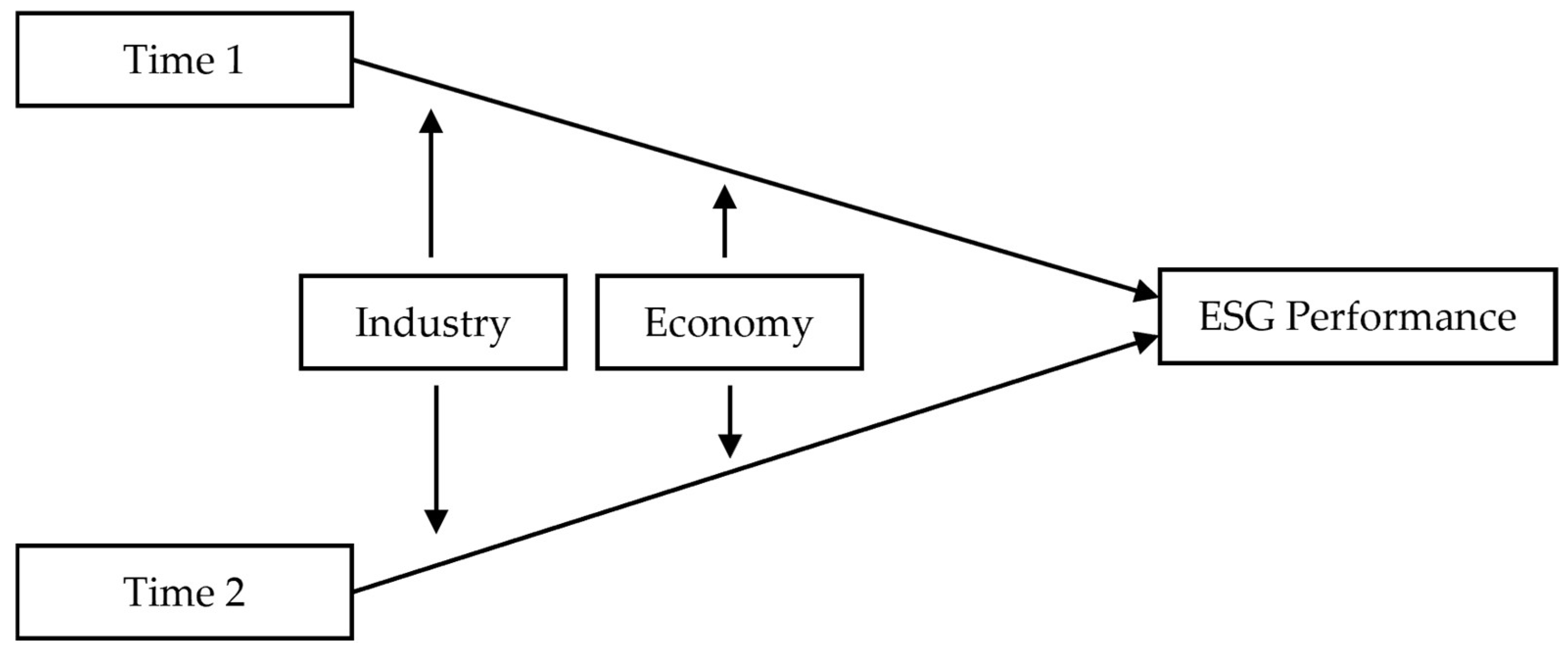

3.2.1. The Piecewise Latent Trajectory Model

3.2.2. Control Variables

3.2.3. Analytical Methods

4. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Policy Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| CBAM | Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism |

| COP 26 | The 26th Conference of Parties |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

| CSRD | Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive |

| EP | Equator Principle |

| FASB | Financial Accounting Standards Board |

| ER | Environmental Rating |

| SR | Social Rating |

| GR | Governance Rating |

| IA | Impact Accounting |

| ISSB | International Sustainability Standards Board |

| ROE | Return on Equity |

| SIC | Standard Industrial Classification |

| SMEs | Small and Medium Enterprises |

| VIF | Variance Inflation Factor |

References

- UNEP. United Nations Environment Programme: Annual Report 2015; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Questions and Answers; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- The Equator Principles Association. About the Equator Principles. Available online: https://equator-principles.com/about-the-equator-principles/ (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Sandberg, H.; Alnoor, A.; Tiberius, V. Environmental, social, and governance ratings and financial performance: Evidence from the European food industry. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2023, 32, 2471–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.; Randers, J.; Meadows, D. Limits to growth: The 30-year update. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2005, 6, 309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneddon, C.S. ‘Sustainability’ in ecological economics, ecology and livelihoods: A review. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2000, 24, 521–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, P.; Singh, J.; Srivastava, D.K.; Mishra, V. Chapter 6—Environmental pollution and sustainability. In Environmental Sustainability and Economy; Singh, P., Verma, P., Perrotti, D., Srivastava, K.K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 111–120. [Google Scholar]

- Boulding, K.E. General systems theory—The skeleton of science. Manag. Sci. 1956, 2, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Understanding the complexity of economic, ecological, and social systems. Ecosystems 2001, 4, 390–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, D.H.; Wright, D. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: White River Junction, VT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Adardour, Z.; Derj, A.; Bami, A.; Hussainey, K. A PRISMA-based systematic review on Economic, Social, and Governance practices: Insights and research agenda. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2025, 34, 1896–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, H.E. Beyond Growth: The Economics of Sustainable Development; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. Chapter 9: Defining and Predicting Sustainability Frontiers in Ecological Economics; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 1997; pp. 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Washington, H.; Maloney, M. The need for ecological ethics in a new ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2020, 169, 106478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paepke, C.O. The Evolution of Progress: The End of Economic Growth and the Beginning of Human Transformation, 1st ed.; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Cumberland, J.H.; Daly, H.; Goodland, R.; Norgaard, R.B. An Introduction to Ecological Economics, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1997; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal, P.; Song, H.-C. Similar but not the same: Differentiating corporate sustainability from corporate responsibility. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2016, 11, 105–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbier, E.B.; Burgess, J.C. The Sustainable Development Goals and the systems approach to sustainability. Economics 2017, 11, 20170028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricotti, P. Corporate responsibility and sustainable development. Symphonya. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2003, 0, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.E. A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Windsor, D. Corporate social responsibility: Three key approaches. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating shared value. In Managing Sustainable Business: An Executive Education Case and Textbook; Lenssen, G.G., Smith, N.C., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 323–346. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Byl, C.A.; Slawinski, N. Embracing tensions in corporate sustainability: A review of research from win-wins and trade-offs to paradoxes and beyond. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A. Corporate citizenship: Toward an extended theoretical conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.B. Corporate Social Responsibility: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, P.C.; Merrill, C.B.; Hansen, J.M. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and shareholder value: An empirical test of the risk management hypothesis. Strateg. Manag. J. 2009, 30, 425–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiu, Y.M.; Yang, S.L. Does engagement in corporate social responsibility provide strategic insurance-like effects? Strateg. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 455–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollman, E. Corporate social responsibility, ESG, and compliance. In The Cambridge Handbook of Compliance; van Rooij, B., Sokol, D.D., Eds.; Cambridge Law Handbooks; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021; pp. 662–672. [Google Scholar]

- Aguinis, H.; Glavas, A. What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2012, 38, 932–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S.; Klein, C.; Zwergel, B. The influence of firm size on the ESG score: Corporate sustainability ratings under review. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 167, 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElAlfy, A.; Palaschuk, N.; El-Bassiouny, D.; Wilson, J.; Weber, O. Scoping the evolution of corporate social responsibility (CSR) research in the sustainable development goals (SDGs) era. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinuzzi, A.; Schönherr, N.; Findler, F. Exploring the interface of CSR and the sustainable development goals. Transnatl. Corp. 2017, 24, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Raulinajtys-Grzybek, M. The application of corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions for mitigation of environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and reputational risk in integrated reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consolandi, C.; Phadke, H.; Hawley, J.; Eccles, R.G. Material ESG outcomes and SDG externalities: Evaluating the health care sector’s contribution to the SDGs. Organ. Environ. 2020, 33, 511–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; Heenetigala, K. Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure for a sustainable development: An Australian study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled, R.; Ali, H.; Mohamed, E.K.A. The sustainable development goals and corporate sustainability performance: Mapping, extent and determinants. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Ceballos, J.; Ortiz-De-Mandojana, N.; Antolín-López, R.; Montiel, I. Connecting the sustainable development goals to firm-level sustainability and ESG factors: The need for double materiality. BRQ Bus. Res. Q. 2022, 26, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziewulska, A.; Lewis, C.W.P. European Environment, Social, and Governance Norms and Decent Work: Seeking a Consensus in the Literature. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, R.Y.J. A review of corporate sustainability reporting tools (SRTs). J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 164, 180–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitols, S. The emerging corporate sustainability reporting system: What role for workers’ representatives? Transf. Eur. Rev. Labour Res. 2023, 29, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.K.; Yang, Y.-F.; Wang, H.; Chen, R.-H.; Zheng, L.J. Mapping the landscape of ESG strategies: A bibliometric review and recommendations for future research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopra, S.S.; Senadheera, S.S.; Dissanayake, P.D.; Withana, P.A.; Chib, R.; Rhee, J.H.; Ok, Y.S. Navigating the challenges of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) reporting: The path to broader sustainable development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, F.; Kölbel, J.F.; Rigobon, R. Aggregate confusion: The divergence of ESG ratings*. Rev. Financ. 2022, 26, 1315–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbey, J.; Ketzenberg, M.; Metters, R. A more profitable approach to product returns. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 71–74. [Google Scholar]

- Del Gesso, C.; Lodhi, R.N. Theories underlying environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure: A systematic review of accounting studies. J. Account. Lit. 2024, 47, 433–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.X.; Sun, Z.; He, K. Toward a sustainable future: ESG as a mediator of innovation and performance under institutional contingencies. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handoyo, S.; Anas, S. The effect of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) on firm performance: The moderating role of country regulatory quality and government effectiveness in ASEAN. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2371071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.; Taglialatela, J.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Determinants of environmental social and governance (ESG) performance: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentinov, V. Advancing a system-level perspective in stakeholder theory: Insights from the institutional economics of John R. Commons. Soc. Sci. Inf. 2024, 63, 443–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.B.; dos Santos, J.I.A.S.; Cherobim, A.P.M.S.; Segatto, A.P. What drives environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance? The role of institutional quality. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2023, 35, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Yuan, X.; Fan, S.; Wang, S. The Impact and mechanism of corporate ESG construction on the efficiency of regional green economy: An empirical analysis based on signal transmission theory and stakeholder theory. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denu, M.K.; Bentley, Y.; Duan, Y. Social sustainability performance: Developing and validating measures in the context of emerging African economies. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 412, 137391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; Shum, W.Y.; Han, T.; Cheong, T.S. Global inequality in service sector development: Trend and convergence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 792950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. A stakeholder theory of the modern corporation. In Perspectives in Business Ethics; McGraw-Hill: Singapore, 1998; pp. 171–181. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, D. Strategic Corporate Social Responsibility: Sustainable Value Creation, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- GRI. Integrating SDGs into Sustainability Reporting. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/public-policy/sustainable-development/integrating-sdgs-into-sustainability-reporting (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Grewal, J.; Serafeim, G. Research on corporate sustainability: Review and directions for future research. Found. Trends® Account. 2020, 14, 73–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, P.; Ruch, G.; Taylor, G. Accounting is the language of sustainability: A measurement framework for carbon accounting. Account. Bus. Res. 2025, 55, 542–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B.A.; Hamdan, A. ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 1409–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. Does corporate social responsibility lead to superior financial performance? A regression discontinuity approach. Manag. Sci. 2015, 61, 2549–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson Brandon, R.; Krueger, P.; Schmidt, P.S. ESG rating disagreement and stock returns. Financ. Anal. J. 2021, 77, 104–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, N.; Sebastianelli, R. Transparency among S&P 500 companies: An analysis of ESG disclosure scores. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 1660–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, T.; Hamori, S.; He, X.; Liu, G.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T. ESG Investment in the Global Economy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Mobarek, A.; Roni, N.N. Revisiting the impact of ESG on financial performance of FTSE350 UK firms: Static and dynamic panel data analysis. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1900500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matakanye, R.M.; van der Poll, H.M.; Muchara, B. Do companies in different industries respond differently to stakeholders’ pressures when prioritising environmental, social and governance sustainability performance? Sustainability 2021, 13, 12022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Tauseef, S. Does an optimal ESG score exist? Evidence from China. Macroecon. Financ. Emerg. Mark. Econ. 2022, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, N.; Caragnano, A.; Zito, M.; Vitolla, F.; Mariani, M. Extending the benefits of ESG disclosure: The effect on the cost of debt financing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1412–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Sun, Y.; Luo, S.; Liao, J. Corporate social responsibility and bank financial performance in China: The moderating role of green credit. Energy Econ. 2021, 97, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper Ho, V. Nonfinancial risk disclosure and the costs of private ordering. Am. Bus. Law J. 2018, 55, 407–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, M. Is ESG the succeeding risk factor? J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2021, 11, 199–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. Corporate governance, ESG, and stock returns around the world. Financ. Anal. J. 2019, 75, 103–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Hamori, S. Can one reinforce investments in renewable energy stock indices with the ESG index? Energies 2020, 13, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, M.; Carrassi, M.; Muserra, A.L.; Wieczorek-Kosmala, M. The impact of the EU nonfinancial information directive on environmental disclosure: Evidence from Italian environmentally sensitive industries. Meditari Account. Res. 2022, 30, 87–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, M.F.; Abdul Rahman, R.; Homayoun, S. Corporate economic, environmental, and social sustainability performance transformation through ESG disclosure. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harasheh, M. Does it make you better off? Initial public offerings (IPOs) and corporate sustainability performance: Empirical evidence. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2022, 23, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Lian, G.; Xu, A. How do ESG affect the spillover of green innovation among peer firms? Mechanism discussion and performance study. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 158, 113648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadstock, D.C.; Chan, K.; Cheng, L.T.W.; Wang, X. The role of ESG performance during times of financial crisis: Evidence from COVID-19 in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A.; Glaum, M.; Kaiser, S. ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Glob. Financ. J. 2018, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.E.; Rothenberg, S. Firm performance: The interactions of corporate social performance with innovation and industry differentiation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2008, 29, 781–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gras, D.; Krause, R. When does it pay to stand out as stand-up? Competitive contingencies in the corporate social performance–corporate financial performance relationship. Strateg. Organ. 2018, 18, 448–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSRHub. Data Schema. Available online: https://www.csrhub.com/csrhub-esg-data-schema (accessed on 28 August 2021).

- Conway, E. To Agree or Disagree? An Analysis of CSR Ratings Firms. Soc. Environ. Account. J. 2019, 39, 152–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiart, C. The correlation between environmental, social and governance ratings and the transparency in Johannesburg Stock Exchange companies’ tax practices. S. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Sci. 2023, 26, 4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan, Y. Preventing modern slavery through corporate social responsibility disclosure: An analysis of the US hospitality and tourism industry. Cornell Hosp. Q. 2024, 1, 120–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.G.; Wu, C.H.; Chang, P.L. The influence of government intervention on the trajectory of bank performance during the global financial crisis: A comparative study among Asian economies. J. Financ. Stab. 2013, 9, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoshi, T.; Kashyap, A.K. Will the U.S. bank recapitalization succeed? Eight lessons from Japan. J. Financ. Econ. 2010, 97, 398–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; An, X. Global financial crisis and emerging stock market contagion: A volatility impulse response function approach. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2016, 36, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littell, R.C.; Milliken, G.A.; Stroup, W.W.; Wolfinger, R.D.; Schabenberger, O. SAS for Mixed Models, 2nd ed.; SAS Institute: Cary, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. OECD Definitions of the ICT Sector, the Content and Media Sector, and Information Industries Based on ISIC Rev. 5. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/oecd-definitions-of-the-ict-sector-the-content-and-media-sector-and-information-industries-based-on-isic-rev-5_b9576889-en.html (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- World Bank. World Bank Country and Lending Groups: Country Classification. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Kim, S.; Li, Z. Understanding the impact of ESG practices in corporate finance. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brammer, S.; Millington, A. Firm size, organizational visibility and corporate philanthropy: An empirical analysis. Bus. Ethic Eur. Rev. 2006, 15, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, R.; Kühnen, M. Determinants of sustainability reporting: A review of results, trends, theory, and opportunities in an expanding field of research. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 59, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, K.V.; Servaes, H.; Tamayo, A.N.E. Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 1785–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT® 15.2 User’s Guide (SAS 9.4); SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, NC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yusifzada, L.; Lončarski, I.; Czupy, G.; Naffa, H. Return trade-offs between environmental and social pillars of ESG scores. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 75, 102779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Rivera, A.; Hannouf, M.; Assefa, G.; Gates, I. Enhancing environmental, social, and governance, performance and reporting through integration of life cycle sustainability assessment framework. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2975–2995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Lu, L.; Wang, S. Environmental regulations, GHRM and green innovation of manufacturing enterprises: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1308224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Emissions Gap Report 2021; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Romolini, A.; Fissi, S.; Gori, E. Scoring CSR reporting in listed companies—Evidence from Italian best practices. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.T.T. China Unveils ESG Reporting Guidelines to Catch Peers. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-05-31/china-unveils-esg-reporting-program-in-bid-to-catch-global-peers?leadSource=uverify%20wall (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Baptista, A.M.C.A.; Serva, C.; Abreu, V. Environmental, Social & Governance Law Brazil 2022–2023. Available online: https://iclg.com/practice-areas/environmental-social-and-governance-law/brazil (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Davids, E.K.R. Environmental, Social & Governance Law South Africa 2022–2023. Available online: https://iclg.com/practice-areas/environmental-social-and-governance-law/south-africa (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Escoto, C.; Romero, M.; Cortés, J.A. Environmental, Social & Governance Law MEXICO 2022–2023. Available online: https://iclg.com/practice-areas/environmental-social-and-governance-law/mexico (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Fenton, S. Russia’s Central Bank Advises Companies to Disclose ESG Agenda; Central Bank of Russia: Moscow, Russia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.; Zhang, S. Research Summary on ESG Policies and Regulations—Russia. Available online: https://www.casvi.org/en/h-nd-1133.html (accessed on 1 March 2022).

- Phua, L.K.; Jalaludin, D.; Wong, C.C. Mandatory sustainability reporting in Malaysia: Impact and internal factors. Bus. Sustain. Innov. 2019, 65, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.P. PLCs Will Be Subject to Higher Sustainability Reporting Standards Soon; The EDGE Malaysia: Petaling Jaya, Malaysia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rego, A.L. Do Brazil’s New ESG Regulations Go Far Enough; BITVORE: Irvine, CA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- SET. Sustainability Highlight 2022. Available online: https://media.set.or.th/set/Documents/2023/Jun/SD_Highlight_2022_ENG.pdf (accessed on 1 June 2023).

- Tungsuwan, P.; Luengwattanakit, P.; Sooppipat, C.; Yi, J.; Sriwasumetharatsami, S. Thailand: Sustainability and Investment Promotion Schemes in Thailand (Part 1); Global Compliance News: Singapore, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, M. ESG reporting: Is It mandatory in India? Available online: https://corpbiz.io/learning/esg-reporting-is-it-mandatory-in-india/ (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Zhou, R.; Lou, J.; He, B. Greening Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance: The Impact of China’s Carbon Emissions Trading Pilot Policy on Listed Companies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, M.B.; Martínez-Ferrero, J. Do emerging and developed countries differ in terms of sustainable performance? Analysis of board, ownership and country-level factors. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2022, 62, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donghui, Z.; Yusoff, W.S.; Salleh, M.F.M.; Lin, N.S.; Jamil, A.H.; Abd Rani, M.J.; Shaari, M.S. The impact of ESG and the institutional environment on investment efficiency in China through the mediators of agency costs and financial constraints. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galleli, B.; Amaral, L. Bridging institutional theory and social and environmental efforts in management: A review and research agenda. J. Manag. 2025, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohendi, H.; Ghozali, I.; Ratmono, D. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure and firm value: The role of competitive advantage as a mediator. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 2297446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardillo, M.A.d.R.; Basso, L.F.C. Revisiting knowledge on ESG/CSR and financial performance: A bibliometric and systematic review of moderating variables. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickmann, T.; Biermann, F.; Sénit, C.-A.; Sun, Y.; Bexell, M.; Bolton, M.; Bornemann, B.; Censoro, J.; Charles, A.; Coy, D.; et al. Scoping article: Research frontiers on the governance of the Sustainable Development Goals. Glob. Sustain. 2024, 7, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biermann, F.; Hickmann, T.; Sénit, C.-A. The Political Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals: Transforming Governance Through Global Goals, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Xie, Y.; He, K. Environmental, social, and governance performance and corporate innovation novelty. Int. J. Innov. Stud. 2024, 8, 109–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019; OECD: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gidage, M.; Bhide, S. ESG and economic growth: Catalysts for achieving sustainable development goals in developing economies. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 2060–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, E.P.Y.; Guo, C.Q.; Luu, B.V. Environmental, social and governance transparency and firm value. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 987–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | N | Mean | StdDev | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 4387 | 58.98 | 9.86 | 14 | 86 |

| SR | 4388 | 54.46 | 8.11 | 18 | 88 |

| GR | 4391 | 52.9 | 8.25 | 23.33 | 85 |

| Industry type | 4428 | 0.49 | 0.5 | 0 | 1 |

| Economy type | 4428 | 0.18 | 0.38 | 0 | 1 |

| Total assets | 4140 | 267,737.11 | 561,212.76 | 0.3 | 5,108,631.27 |

| Market value | 3840 | 65,549.58 | 119,848.25 | 6 | 2,413,423.40 |

| ROE | 3978 | 14.96 | 35.44 | −240.02 | 1048.62 |

| Firm age | 4428 | 77.38 | 51.27 | 8 | 357 |

| Revenue | 4143 | 61,769.91 | 57,618.21 | 201.43 | 559,151 |

| ER | SR | GR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 60.9516 | *** | 52.4265 | *** | 55.2082 | *** |

| T1 | 0.2335 | 0.0124 | 0.1940 | |||

| T2 | 0.4334 | ** | 0.2357 | ** | 0.4373 | ** |

| Industry type | −3.9828 | *** | −1.4913 | −0.8034 | ||

| Economy type | −4.7989 | *** | −3.1565 | −0.5259 | ||

| Total assets | 0.0007 | *** | 0.0013 | *** | 0.0033 | *** |

| Market value | −0.0027 | −0.0023 | 0.0046 | |||

| ROE | 0.0013 | −0.0041 | 0.0002 | |||

| Firm age | 0.0128 | 0.0149 | ** | 0.0174 | ** | |

| Revenue | −0.0100 | 0.0000 | *** | 0.0000 | *** | |

| T1 × Industry type | 0.3629 | −0.4024 | 0.2041 | |||

| T2 × Industry type | 0.6545 | *** | 0.2537 | −0.1481 | ||

| T1 × Economy type | 1.3873 | *** | 1.6683 | *** | 1.5579 | *** |

| T2 × Economy type | −0.1397 | −0.3565 | *** | −0.6502 | *** | |

| T1 × Total assets | 0.0005 | *** | 0.0000 | *** | 0.0000 | *** |

| T1 × Market value | −0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | |||

| T1 × Firm age | 0.0013 | −0.0027 | −0.0006 | |||

| T1 × Revenue | 0.0026 | −0.0051 | −0.0030 | |||

| T1 × ROE | −0.001 | −0.0026 | −0.0012 | |||

| T2 × Total assets | 0.0003 | *** | −0.0002 | *** | −0.0004 | *** |

| T2 × Market value | 0.0008 | *** | 0.0005 | *** | −0.0009 | *** |

| T2 × Firm age | −0.0003 | −0.0021 | * | −0.0023 | * | |

| T2 × Revenue | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | *** | 0.0000 | *** | |

| T2 × ROE | 0.0009 | 0.0029 | 0.0001 | |||

| Observations | 3679 | 3684 | 3683 | |||

| Log likelihood | 23,480.5 | 22,736.0 | 21,245.6 | |||

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | 23,542.5 | 22,798.0 | 21,307.6 | |||

| X2 | 2561.77 | *** | 2506.89 | *** | 3984.05 | *** |

| Before (2010–2015) | After (2016–2021) | After–Before | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ER | 0.8149 | 0.9074 | 0.0925 |

| SR | 0.4857 | 0.2466 | −0.2390 |

| GR | −0.3019 | 0.2401 | 0.5419 *** |

| Before (2010–2015) | After (2016–2021) | After–Before | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER | ||||||

| Developed Economy | ||||||

| Manufacturing Industry | 0.5964 | * | 1.0879 | *** | 0.4915 | |

| Service Industry | 0.2335 | 0.4334 | * | 0.1999 | ||

| Developing Economy | ||||||

| Manufacturing Industry | 1.9836 | *** | 0.9482 | *** | −1.0354 | * |

| Service Industry | 1.6207 | *** | 0.2937 | −1.3270 | ** | |

| SR | ||||||

| Developed Economy | ||||||

| Manufacturing Industry | 0.3981 | 0.2892 | * | −0.1089 | ||

| Service Industry | 0.1940 | 0.4373 | ** | 0.2433 | ||

| Developing Economy | ||||||

| Manufacturing Industry | 1.9559 | *** | −0.3610 | *** | −2.3169 | *** |

| Service Industry | 1.7518 | *** | −0.2129 | −1.9647 | *** | |

| GR | ||||||

| Developed Economy | ||||||

| Manufacturing Industry | −0.3900 | 0.4894 | *** | 0.8794 | ** | |

| Service Industry | 0.0124 | 0.2357 | 0.2233 | |||

| Developing Economy | ||||||

| Manufacturing Industry | 1.2783 | *** | 0.1329 | −1.1454 | ** | |

| Service Industry | 1.6807 | *** | −0.1208 | −1.8015 | *** | |

| Parameter | ER | SR | GR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random effects | |||

| Intercept variance (UN) | 16.61 | 26.68 | 43.57 |

| Slope 1 variance (pre, UN) | 1.89 | 2.18 | 1.36 |

| Slope 2 variance (post, UN) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intercept–Slope 1 covariance (UN) | −3.38 | −1.32 | −2.82 |

| Intercept–Slope 2 covariance (UN) | 1.38 | −1.24 | −3.87 |

| Slope 1–Slope 2 covariance (UN) | 0.66 | 0.17 | 0.52 |

| Serial correlation | |||

| AR(1) residual correlation () | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.56 |

| Residual variance | 36.27 | 24.17 | 23.06 |

| Variable Pair | Observations | Correlation | ER | SR | GR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total assets | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 | |||

| Market value | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 | |||

| ROE | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 | |||

| Firm age | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |||

| Revenue | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.27 | |||

| Total assets–Market value | 3840 | 0.09 | *** | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.06 |

| Total assets–ROE | 3978 | −0.06 | ** | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 |

| Total assets–Firm age | 4140 | −0.05 | ** | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 |

| Total assets–Revenue | 4137 | 0.20 | *** | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.27 |

| Market value–ROE | 3709 | 0.14 | *** | 1.26 | 1.26 | 1.26 |

| Market value–Firm age | 3840 | −0.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

| Market value–Revenue | 3839 | 0.43 | *** | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.27 |

| ROE–Firm age | 3978 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 | |

| ROE–Revenue | 3977 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 1.03 | |

| Firm age–Revenue | 4143 | −0.02 | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, E.M.; Cheng, J.-H. The Evolution of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance: A Longitudinal Comparative Study on Moderators of Agenda 2030. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198568

Chang EM, Cheng J-H. The Evolution of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance: A Longitudinal Comparative Study on Moderators of Agenda 2030. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198568

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Eric M., and Jo-Han Cheng. 2025. "The Evolution of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance: A Longitudinal Comparative Study on Moderators of Agenda 2030" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198568

APA StyleChang, E. M., & Cheng, J.-H. (2025). The Evolution of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance: A Longitudinal Comparative Study on Moderators of Agenda 2030. Sustainability, 17(19), 8568. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198568