Sustainable Transformation of Post-Mining Areas: Discreet Alliance of Stakeholders in Influencing the Public Perception of Heavy Industry in Germany and Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Post-Mining Areas and Heavy Industry

1.2. Public Spaces in Post-Mining Areas and “Wild” Greenery

1.3. Public Spaces in Mining-Related Areas

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials: Case Study Analysis

2.1.1. Cases of Revitalised Spaces in the Vicinity of Active Mining Areas in Germany

2.1.2. Cases of Revitalised Spaces in the Vicinity of Active Mining Areas in Poland

2.1.3. The Cases That Characterise the Paradigm

2.2. Methods

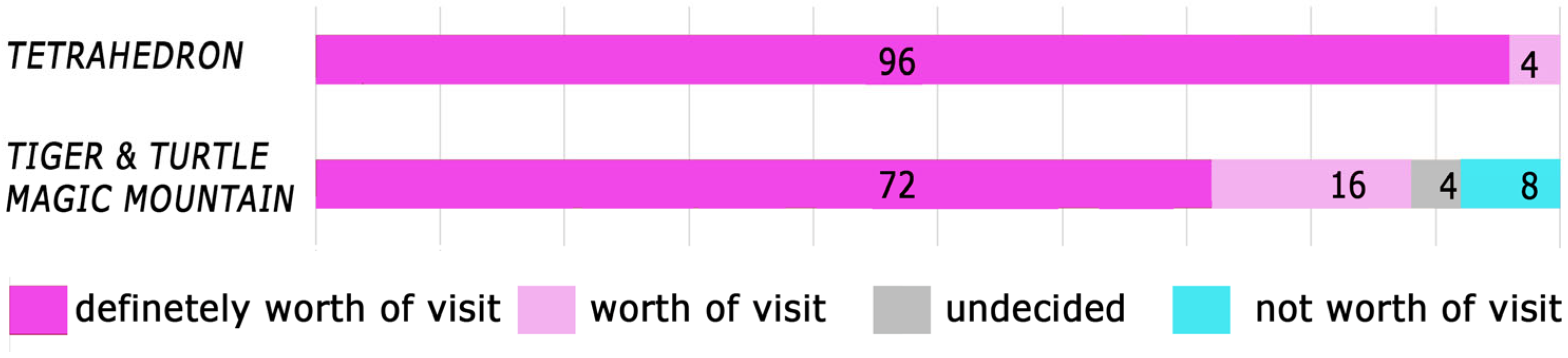

2.2.1. Empirical–Analytical In Situ Research—Quantitative and Qualitative in Germany

2.2.2. Implementation–Verification Study (Research Through Design) in Poland

3. Results

3.1. Public Spaces Adjacent to Active Industrial Areas in Germany

3.1.1. German “Signs of Change”

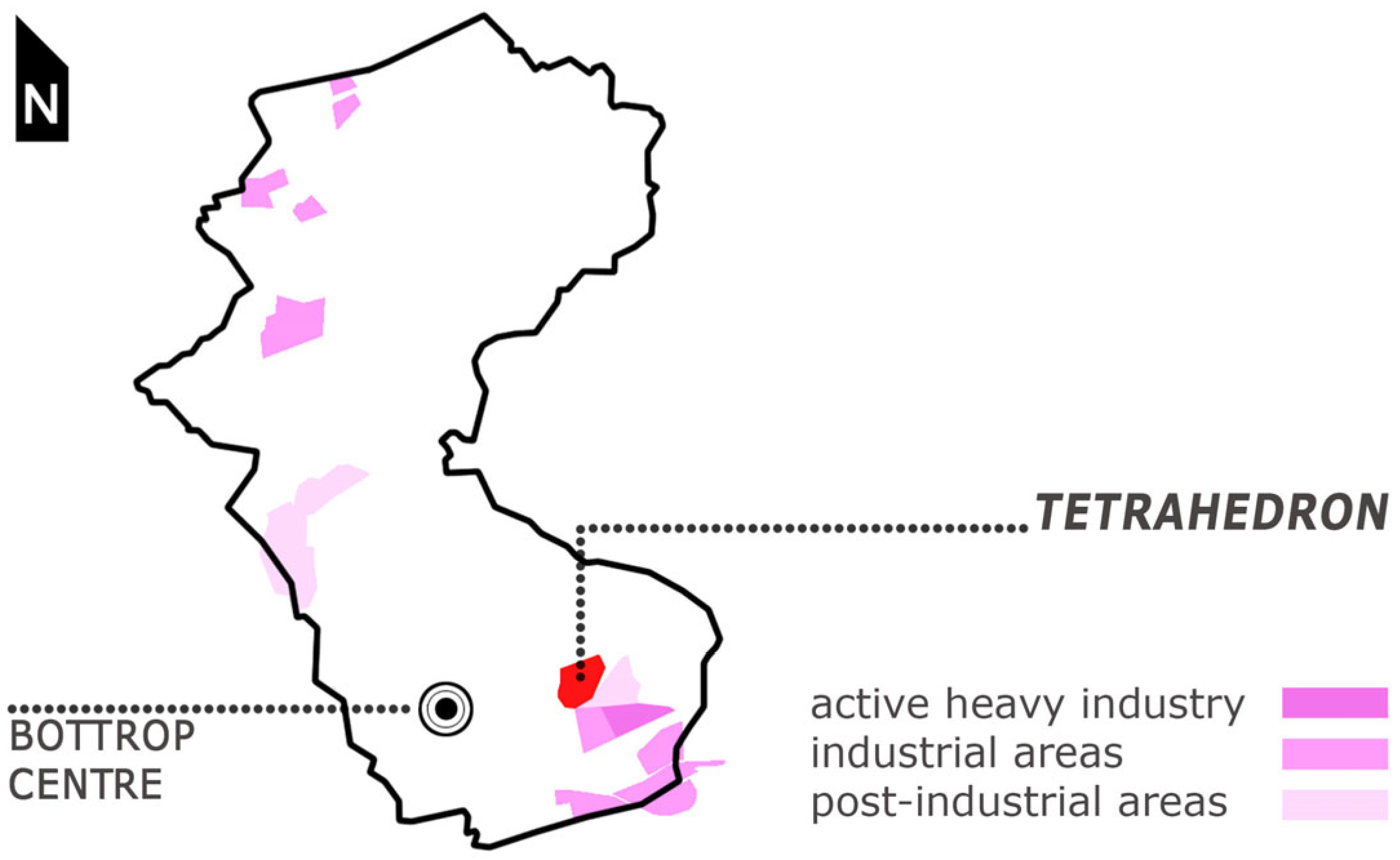

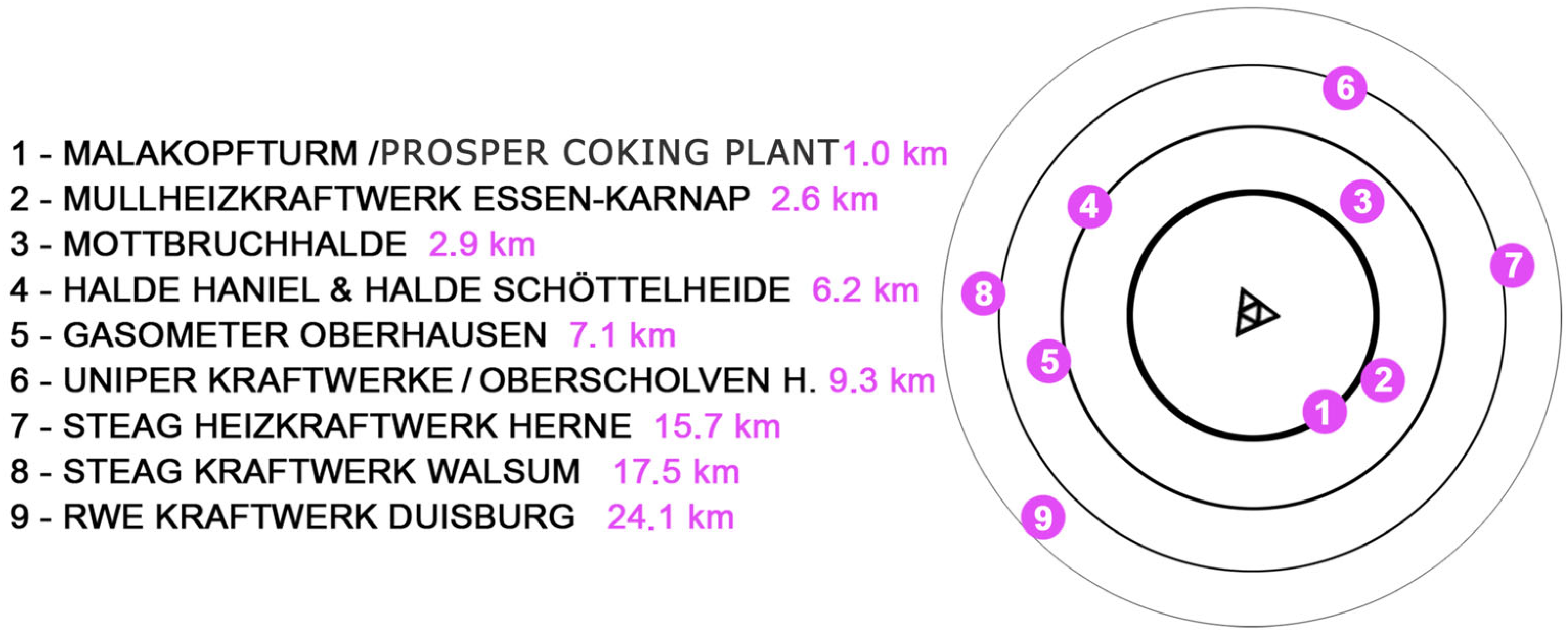

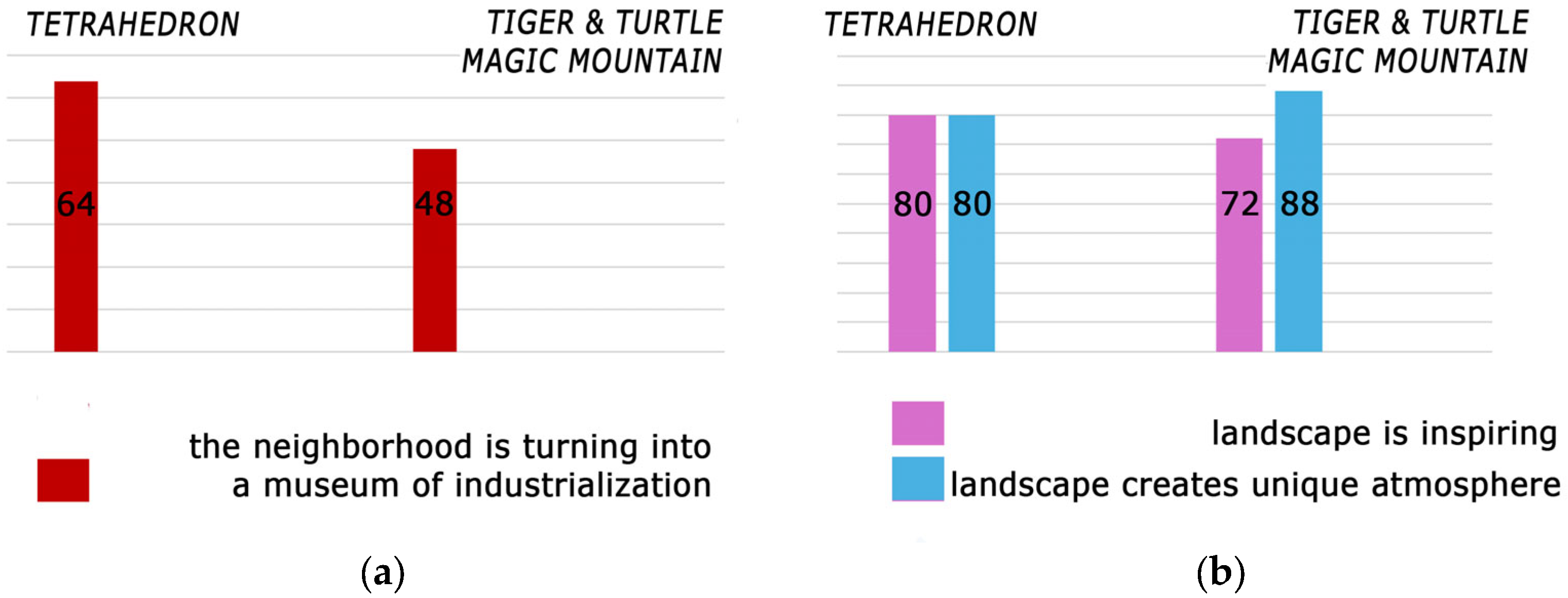

3.1.2. Case Study—Tetrahedron in Bottrop, Beckstraße Spoil Heap: Active Industry as a Landscape Element

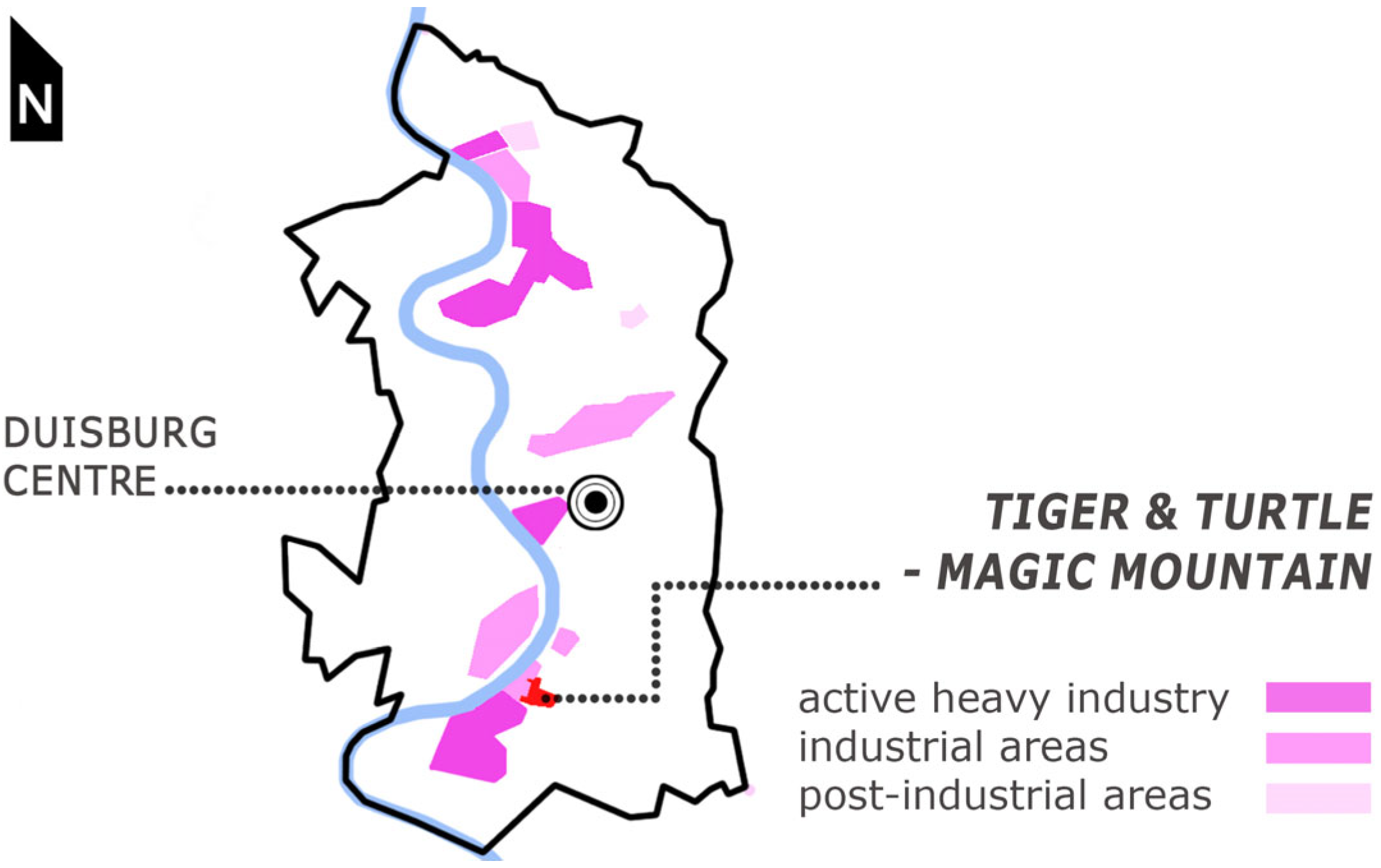

3.1.3. Case Study—Tiger & Turtle—Magic Mountain in Duisburg on a Gravel Pit Converted to a Hazardous Waste Landfill: Active Industry Transforming the Landscape

3.1.4. Understanding the Landscape in Germany

3.2. Public Spaces Adjacent to Industry in Poland

3.2.1. Polish “Signs of Change”

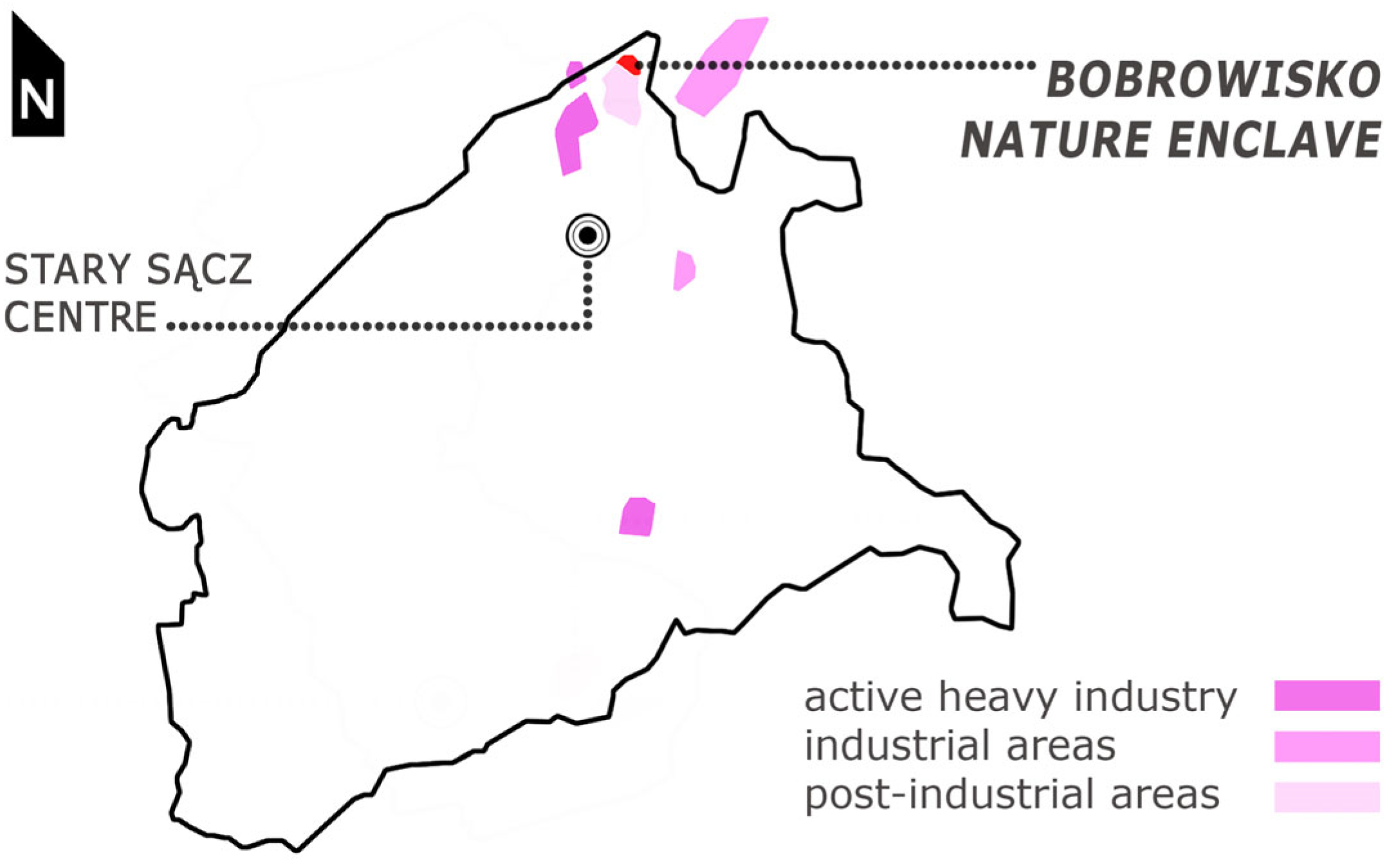

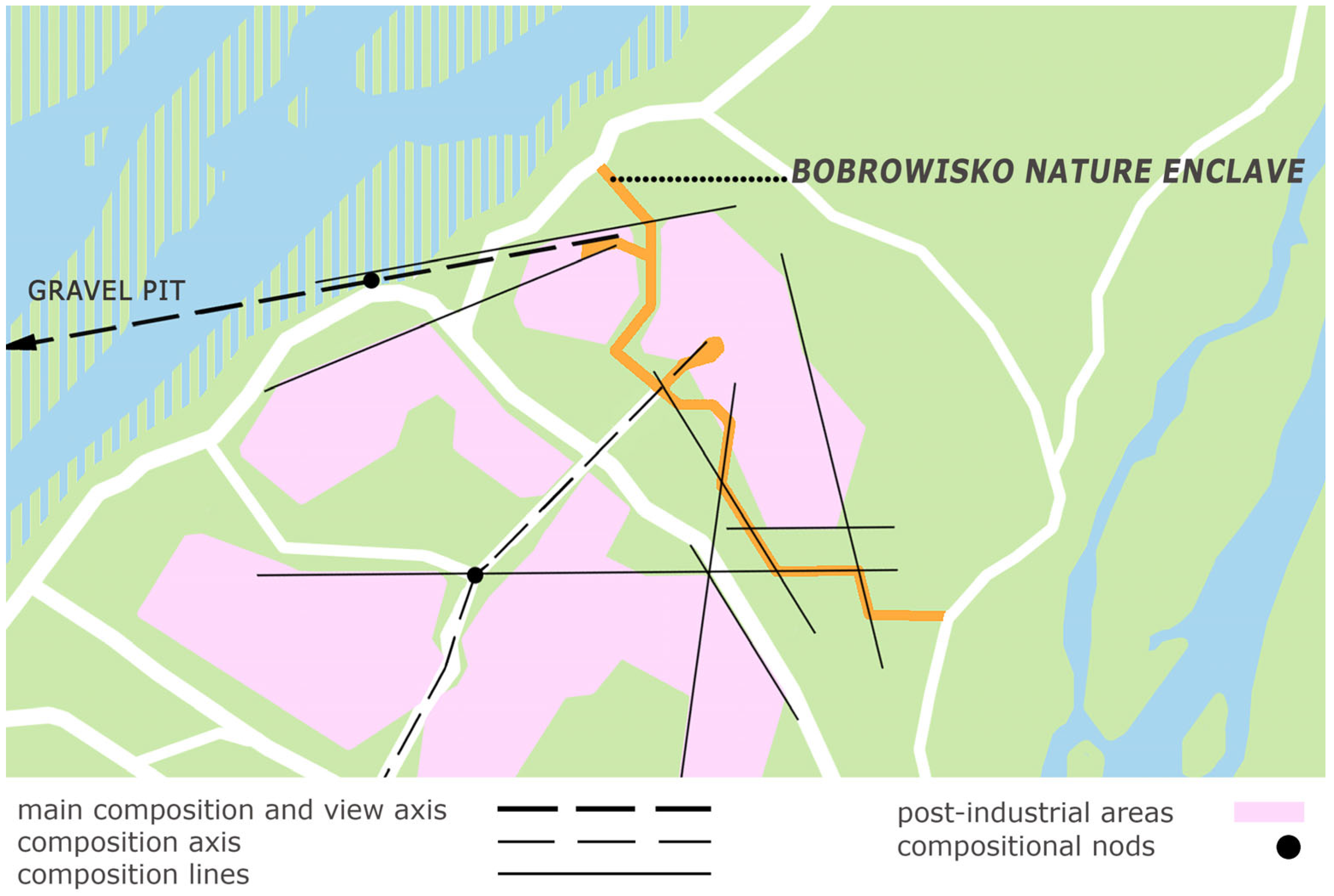

3.2.2. Bobrowisko Nature Enclave—Industry Creates an Attractive Landscape

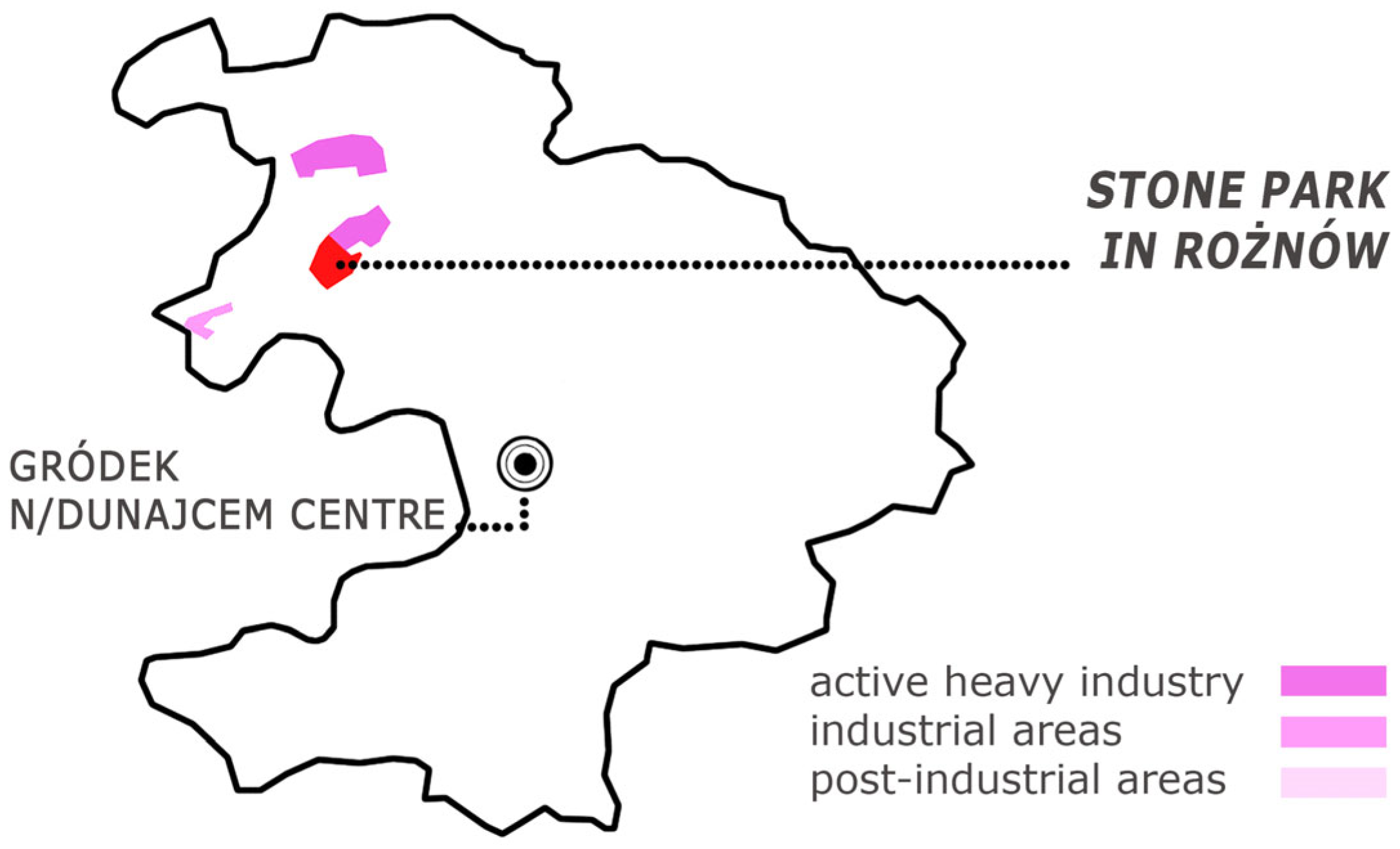

3.2.3. Stone Park in Rożnów (Gródek n/Dunajcem Commune)—Industry Actively Creates an Attractive Landscape

3.2.4. “Understanding the Landscape” in Poland

4. Discussion

- Existing analyses of “signs of change” do not consider the influence of political decisions on spatial solutions, which leads to a limited understanding of the role they play in the sustainable transformation of areas in transition;

- Public spaces in the vicinity of industrial areas have been designed to draw users’ attention to specific landscape features—namely, areas of active industry—and a preliminary study of public opinion reveals that visitors may be focused mainly on their aesthetic qualities;

- Projects that emphasise the presence of nearby industry are designed as a kind of education and mediation tool between communities and industry, accommodating the real (slow) pace of change (however, their effectiveness requires further research);

- The construction of public spaces adjacent to active industry are planned to connect social and economic interests.

4.1. “Signs of Change” and the Need for a Change in Perception

4.2. Spatial Solutions for Understanding the Landscape

4.3. Public Spaces in the Vicinity of Industry as a Tool for Education and Mediation Between Communities and Industry

4.4. Social Corporate Responsibility of Community Representatives

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions: Revitalising and Maintaining Heavy Industry

- The visual and compositional linkages in the cases demonstrate that the landmarks were deliberately designed to emphasise the visibility of active industrial facilities in their vicinity;

- The promotion by local governments of the policy of sharing the same territory between industry and recreation reflects a deliberate effort to shape attitudes favourable to industrial activities, which provide revenues to local budgets;

- “Signs of change” in the landscape have been built to focus users’ attention on the representation of heavy industry and intended to keep them in operation, despite the ongoing transformation—they are not designed to change the function of these facilities, but rather to change how they are perceived;

- Revitalisation based on specific spatial solutions that emphasise the visibility of areas commonly regarded as environmentally degrading can serve to educate, maintain or secure the social legitimacy of heavy industry, including mining, either in the spirit of sustainable development or as a practice that opens the possibility of manipulating public opinion (without implementing solutions that actually aim at sustainable development);

- Discrete alliances aimed at influencing user opinions through spatial solutions can be formed in various cultural contexts;

- Stakeholders try to influence users’ opinions about active industries through spatial solutions, but their effectiveness requires further research.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Luger, J.; Schwarze, T. Leaving Post-industrial Urban Studies Behind? Dialogues Urban Res. 2024, 2, 188–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mah, A. Anticipating Just Transitions. In The Routledge International Handbook of Deindustrialization Studies; Strangleman, T., Linkon, S.L., High, S., Clarke, J., Berger, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar]

- Cała, M.; Szewczyk-Świątek, A.; Ostręga, A. Challenges of Coal Mining Regions and Municipalities in the Face of Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 6674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enemuo, M.; Ogunmodimu, O. Transitioning the Mining Sector: A Review of Renewable Energy Integration and Carbon Footprint Reduction Strategies. Appl. Energy 2025, 384, 125484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostręga, A.; Szewczyk-Świątek, A.; Cała, M.; Dybeł, P. Obsolete Mining Buildings and the Circular Economy on the Example of a Coal Mine from Poland—Adaptation or Demolition and Building Anew? Sustainability 2024, 16, 7493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanz, F.; Pendlebury, J. Adaptive Reuse: A Critical Review. J. Archit. 2022, 27, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahac, M.; Gašparović, S.; Šmit, K. Infrastructure in Post-industrial Urban Landscapes. In The Reimagining of Urban Spaces; Applied Innovation and Technology Management; Lakušić, S., Pavičić, J., Stojčić, N., Scholten, P.W.A., van Sinderen Law, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivý, M. Speculative redevelopment and conservation: The signifying role of architecture. City 2011, 15, 42–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivý, M. The Smart and the Ruined: Notes on the New Social Factory. Thresholds 2019, 47, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk-Światek, A. Architecture and Active Heavy Industry: On Initiatives Influencing the Social Perception of Industry in Light of German and Polish Experiences with the Revitalization of Mining-Related Areas. Ph.D. Thesis, Cracow University of Technology, Krakow, Poland, 2023. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/47693 (accessed on 2 May 2025). (In Polish).

- Maesham, T.; Walker, J.; McKenzie, F.H.; Kirby, J.; Williams, C.; D’Urso, J.; Littleboy, A.; Samper, A.; Rey, R.; Maybee, B.; et al. Beyond Closure: A Literature Review and Research Agenda for Post-mining Transitions. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minister für Stadtentwicklung, Wohnen und Verkehr des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. Internationale Bauausstellung Emscher-Park: Werkstatt für die Zukunft alter Industriegebiete: Memorandum zu Inhalt und Organisation; Archiwum Stiftung Geschichte des Ruhrgebiets; Minister für Stadtentwicklung, Wohnen und Verkehr des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, S. Introduction: Memories, Memorialization, and the Heritage of Deindustrialization. In The Routledge International Handbook of Deindustrialization Studies; Strangleman, T., Linkon, S.L., High, S., Clarke, J., Berger, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, E. The Musealization of Barcelona’s Industrial Past. Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain, 2020. Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/tesis/2021/hdl_10803_671929/edso1de1.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Shaw, R. The International Building Exhibition (IBA) Emscher Park, Germany: A Model for Sustainable Restructuring? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keenan, J.; Holcombe, S. Mining as a Temporary Land Use: A Global Stocktake of Postmining Transitions and Repurposing. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2021, 8, 100924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagouni, C.; Pavloudakis, F.; Kapageridis, I.; Yiannakou, A. Transitional and Post-Mining Land Uses: A Global Review of Regulatory Frameworks, Decision-Making Criteria, and Methods. Land 2024, 13, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukopp, H. On the Early History of Urban Ecology in Europe. Preslia Praha 2002, 74, 373–393. [Google Scholar]

- Box, J. Nature Conservation and Post-Industrial Landscapes. Ind. Archaeol. Rev. 1999, 21, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonincontro, T.; Cerceau, J.; Tena-Chollet, F.; Beccera, S. From Unseen to Seen in Post-Mining Polluted Territories: (In)visibilisation processes at work in soil contamination management. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivý, M. Fitness Urbanism. In Proceedings of the Platform Austria, Biennale Architettura, Venice, Italy, 22 May–21 July 2021; Available online: https://www.platform-austria.org/en/blog/fitness-urbanism (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Bole, D.; Kumer, P.; Gašperič, P.; Kozina, J.; Pipan, P.; Tiran, J. Clash of Two Identities: What Happens to Industrial Identity in a Post-Industrial Society? Societies 2022, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Connolly, J.J.T.; Cole, H.; Garcia-Lamarca, M.; Triguero-Mas, M.; Baró, F.; Martin, N.; Conesa, D.; Shokry, G.; del Pulgar, C.P.; et al. Green Gentrification in European and North American Cities. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovira, J.; Nadal, M.; Schuhmacher, M.; Domingo, J.L. Environmental impact and human health risks of air pollutants near a large chemical/petrochemical complex: Case study in Tarragona, Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 787, 147550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onifade, M.; Adetunji Adebisi, J.; Penda Shivute, A.; Genc, B. Challenges and applications of digital technology in the mineral industry. Resour. Policy 2023, 85B, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyashenko, V.I.; Golik, V.I.; Klyuev, R.V. Evaluation of the efficiency and environmental impact (on subsoil and groundwater) of underground block leaching (UBL) of metals from ores. Min. Sci. Technol. 2022, 7, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christ, W.; Maiwurm, C.; Plum, S.; Witte, A. Haldenereignis—Emscherblick: Eine Denkschrift; Archiv UI-Institut: Bottrop, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Christ, W. Haldenereignis Emschrblick Bottrop. 1994. Available online: https://www.mediastadt.com/projekte/tetraeder/tetraeder.html (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Dettmar, J. Rekultivierung von Bergehalden im Ruhrgebiet: Beobachtungen und Erfahrungen. In Bergbau und Umwelt in DDR und BRD: Praktiken der Umweltpolitik und Rekultivierung; Albrecht, H., Farrenkopf, M., Eds.; De Gruyter Oldenbourg: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 163–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinkla, S.; Greulich, P. (Eds.) Tiger & Turtle—Magic Mountain: A Landmark in Duisburg by Heike Mutter and Ulrich Genth; Hatje Cantz: Duisburg, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Polish Geological Institute National Research Institute. Sand and Gravel (Natural Aggregates). 2024. Available online: https://www.pgi.gov.pl/en/mineral-resources/rock-raw-materials-and-others/sand-and-gravel-natural-aggregates.html (accessed on 27 July 2025).

- Agamben, G. (Ed.) What Is a Paradigm? In The Signature of All Things: On Method; Zone Books: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, K. The Image of the City, 12th ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Svobodova, K.; Barták, V.; Hendrychová, M. Visiting Mine Reclamation: How Field Experience Shapes Perceptions of Mining. Ambio 2025, 54, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frayling, C. Research in Art and Design. R. Coll. Arts Pap. 2014, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wicke, C. Introduction: Industrial Heritage and Regional Identities. In Industrial Heritage and Regional Identities; Wicke, C., Berger, S., Golombek, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Weilacher, U. Rusty-brown and Phacelia Blue—Landmark Art by the IBA. Topos 1999, 26, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, C. Bergbau, Tagebau, Umbau: The Post-Industrial Landscape Aesthetic of Repurposed Coal Mines in Germany. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Michigan, Ann Arbour, MI, USA, 2019. Available online: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/153435 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Budinger, A.; Schmitt, H.C.; Ze, M.; Karulska, O.; Wenning, T. Heap Development in the Ruhr Metropolis. The ‘Mountains of the Ruhr’ as Places of Identity. In Proceedings of the Space For Species: Redefining Spatial Justice, AESOP Annual Congress. Tartu, Estonia, 25–29 July 2022; Available online: https://proceedings.aesop-planning.eu/index.php/aesopro/issue/view/14/14 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Press Office of the Malopolska Voivodeship Marshal’s Office. The Bobrowisko in Stary Sącz is Open to Residents. 2018. Available online: https://www.malopolska.pl/aktualnosci/fundusze-europejskie/bobrowisko-w-starym-saczu-otwarte-dla-mieszkancow (accessed on 9 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Starosadeckie.info. PLN 1.3 Million for the Protection of Biodiversity in Stary Sącz. 2016. Available online: https://www.starosadeckie.info/wydarzenia/13-mln-zl-ochrone-bioroznorodnosci-starym-saczu/ (accessed on 13 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Świątek, W. The Role of the Objects of Cultural Expression in Defining Significant Places in the Landscape. Ph.D. Thesis, Cracow University of Technology, Krakow, Poland, 2021. Available online: https://repozytorium.biblos.pk.edu.pl/resources/44846 (accessed on 9 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Sądeczanin.info. The Bobrowisko Enclave in Stary Sącz is Simply Sexy! 2018. Available online: https://sadeczanin.info/wiadomosci/enklawa-bobrowisko-w-starym-saczu-jest-po-prostu-sexy-wideo (accessed on 9 August 2025). (In Polish).

- The Association of Polish Architects (Stowarzyszenie Architektów Polskich, SARP). Competition SARP Award of the Year, 2019 Edition. 2019. Available online: https://www.sarp.pl/pokaz/konkurs_nagroda_roku_sarp-_edycja_2019,2719/ (accessed on 9 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Gazeta Krakowska. A New Attraction is to Be Built at Lake Rożnów, Inspired by the Famous Bobrowisko: An Old Gravel Pit Will Be Transformed into a Spectacular Park. 2025. Available online: https://gazetakrakowska.pl/nad-jeziorem-roznowskim-ma-powstac-nowa-atrakcja-inspiracja-slynne-bobrowisko-stara-zwirownia-zamieni-sie-w-zjawiskowy-park/ar/c1p2-27334523 (accessed on 10 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Dunajec Wodociągi. Gravel Pit General Information. 2025. Available online: https://dunajec-grodek.pl/Informacje-ogolne (accessed on 9 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Rejestr.io Wyszukiwarka danych z KRS. Dunajec. 2025. Available online: https://rejestr.io/krs/282163/dunajec (accessed on 9 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Drabon, N.; Knoll, A.H.; Lowe, R.; Bernasconi, S.M.; Brenner, A.R.; Mucciarone, D.A. Effect of a Giant Meteorite Impact on Paleoarchean Surface Environments and Life. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2408721121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radio Krakow. Former Gravel Pit, There Will Be a New Attraction at Lake Rożnów. 2025. Available online: https://www.radiokrakow.pl/aktualnosci/nowy-sacz/byla-zwirownia-bedzie-nowa-atrakcja-nad-jeziorem-roznowskim/ (accessed on 10 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Dts24. News from Sądeczyzna Region. A Quiet Space for Strolling: Stone is the Main Motif of the Relaxation Zone in Rożnów. 2025. Available online: https://www.dts24.pl/cicha-przestrzen-do-spacerow-kamien-motywem-przewodnim-strefy-relaksu-w-roznowie/ (accessed on 10 August 2025). (In Polish).

- Facebook. Jarosław Baziak Mayor of Grodek on Dunajec Comune Profile. 2025. Available online: https://www.facebook.com/jaroslawbaziak/posts/122199293222133158?ref=embed_post (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Fraser, J. Mining companies and communities: Collaborative approaches to reduce social risk and advance sustainable development. Resour. Policy 2021, 74, 101144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudrun, F.; Schütte, P. Current trends in addressing environmental and social risks in mining and mineral supply chains by regulatory and voluntary approaches. Miner. Econ. 2022, 35, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Singh, S.; Nangia, P.; Chanaliya, N.; Sala, D. Sustaining the mining industry through the lens of corporate social responsibility: A review research. Resour. Policy 2024, 99, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganser, K. Eine Baustellungim in Hübsch-Hässlicher Umgebung. Forum Ind. Geschichtskultur 2009, 1, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, J.F. A Diversity of Approaches to Visual Impact Assessment. Land 2022, 11, 1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, V.; Lai, A.; Pina, F.; Cigagna, M.; Massacci, G.; Grosso, B. A Comprehensive Methodology for the Visual Impact Assessment of Mines and Quarries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2023, 102, 107199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwazer, R.H. Borrowed Sceneries; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, G. Pochwała profanacji (en. In Praise of Profanation). In Profanacje (en. Profanations); Agamben, G., Ed.; PIW: Warszawa, Poland, 2005; pp. 93–116. [Google Scholar]

- Höfer, W.; Vicenzotti, V. Post-industrial Landscapes: Evolving Concepts. In The Routledge Companion to Landscape Studies, 2nd ed.; Howard, P., Thompson, I., Waterton, E., Atha, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 499–510. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V. A Preliminary Study on Industrial Landscape Planning and Spatial Layout in Belgium. Heritage 2021, 4, 1375–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, M. Narodziny Biopolityki (en. The Birth of Biopolitics); PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Awan, N.; Schneider, T.; Till, J. Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Grodach, C.; Hatuka, T.; Ferm, J.; Danan Vincent, A.; Merve Nalçakar, E.; Çalışkan, O.; Chang, R.A. Industrial Lands and Development. Plan. Theory Pract. 2024, 25, 699–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouresmaieli, M.; Ataei, M.; Qarahasanlou, A.N.; Barabadi, A. Corporate Social Responsibility in Complex Systems Based on Sustainable Development. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Chen, D. Issues of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Mining Industry: The Case of China. Resour. Policy 2022, 76, 102648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pons, A.; Vintrò, C.; Josep Rius, J.; Jordi Vilaplana, J. Impact of Corporate Social Responsibility in mining industries. Resour. Policy 2021, 72, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szewczyk-Świątek, A.; Ostręga, A.; Cała, M.; Beese-Vasbender, P. Utilizing Circular Economy Policies to Maintain and Transform Mining Facilities: A Case Study of Brzeszcze, Poland. Resources 2024, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Moyano, J.A.; Remolar, I.; Gómez-Cambronero, Á. Augmented Reality’s Impact in Industry—A Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2025; UNSD: New York, NY, USA, 2025; Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 19 September 2025).

| Name of Case Study (Country) | Tetrahedron (DE) | Tiger & Turtle—Magic Mountain (DE) | Bobrowisko Nature Enclave (PL) | Stone Park (PL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 40 ha | 12.3 ha | 3.5 ha | 8 ha |

| Budget | EUR 1.2 M | EUR 2 M | EUR 0.36 M | EUR 1.06 M |

| Funding | EUR 1.1 M regional ecological programme + EUR 0.1 M the municipality’s own funds | EUR 1.8 M regional funds and regional ecological programme + EUR 0.2 M European Capital of Culture Fund and sponsors | EUR 0.31 M regional funds + EUR 0.05 M the municipality’s own funds | Not disclosed |

| Year | 1995 | 2011 | 2018 | 2025 |

| Social effects | Meeting and view point with the public space in the formerly degraded area | Meeting and view point with the public space in the formerly degraded area | Lookout and the public space in the formerly isolated area | Lookout points and the public space in the formerly excluded area |

| Environmental effects | Reclamation of the spoil heap | Reclamation of gravel pit and slag heap (hazardous waste landfill) | Conservation of natural succession in the former gravel pit area | Revitalisation of the gravel pit |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szewczyk-Świątek, A. Sustainable Transformation of Post-Mining Areas: Discreet Alliance of Stakeholders in Influencing the Public Perception of Heavy Industry in Germany and Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198567

Szewczyk-Świątek A. Sustainable Transformation of Post-Mining Areas: Discreet Alliance of Stakeholders in Influencing the Public Perception of Heavy Industry in Germany and Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198567

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzewczyk-Świątek, Anna. 2025. "Sustainable Transformation of Post-Mining Areas: Discreet Alliance of Stakeholders in Influencing the Public Perception of Heavy Industry in Germany and Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198567

APA StyleSzewczyk-Świątek, A. (2025). Sustainable Transformation of Post-Mining Areas: Discreet Alliance of Stakeholders in Influencing the Public Perception of Heavy Industry in Germany and Poland. Sustainability, 17(19), 8567. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198567