The Impact of Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance on Total Factor Productivity: An Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. The Impact of Corporate ESG Performance on TFP

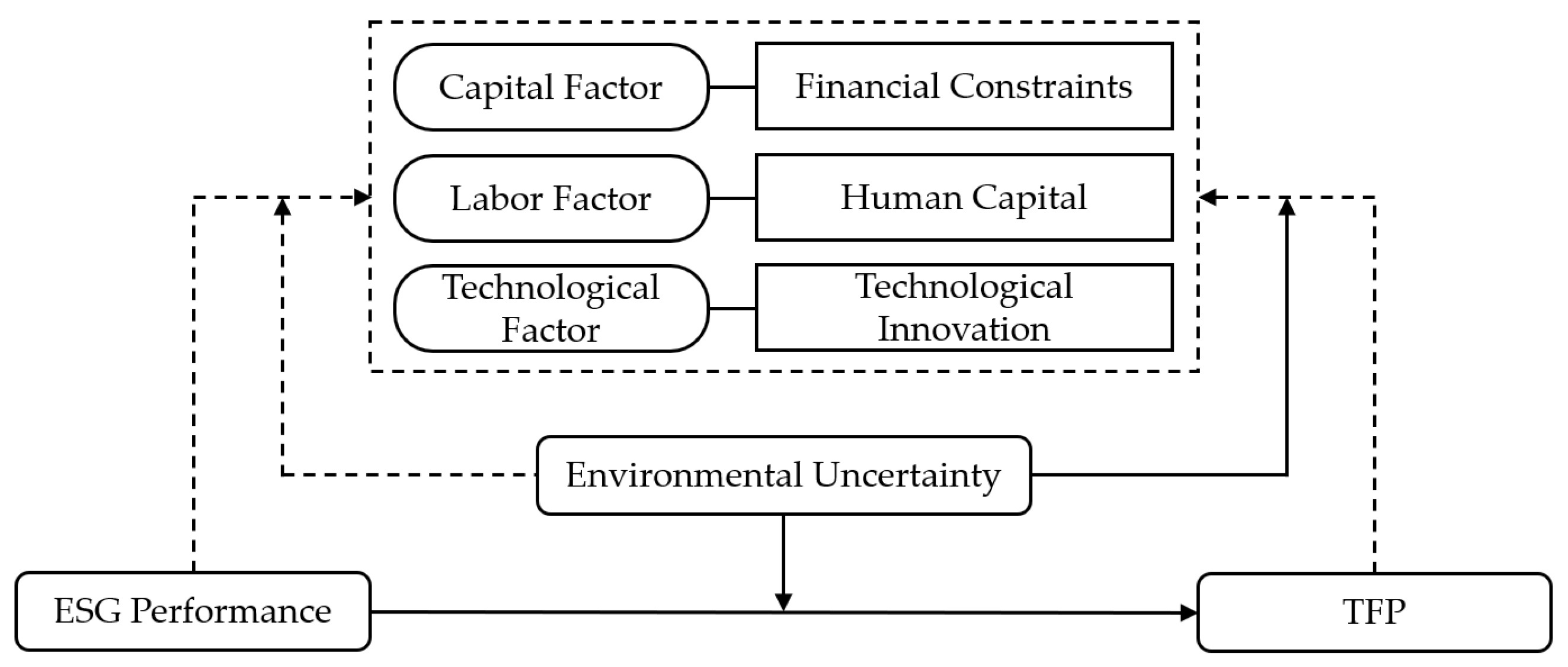

2.2. Transmission Mechanisms of ESG Performance on TFP

2.2.1. Capital Factor

2.2.2. Labor Factor

2.2.3. Technological Factor

2.3. The Moderating Role of Environmental Uncertainty

3. Research Design

3.1. Baseline Model Specification

3.2. Variable Selection, Measurement, and Data Sources

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Baseline Regression Analysis

4.3. Robustness Tests

4.4. Endogeneity Tests

4.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.5.1. Heterogeneity Analysis by Industry Characteristics

4.5.2. Heterogeneity Analysis by Ownership Type

4.5.3. Heterogeneity Analysis by Environmental Risk Exposure

4.6. Mechanism Analysis

5. Extended Analysis

5.1. Moderating Effect of

5.2. Mechanism Analysis of ’s Moderating Effect

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

6.1. Conclusions

- (1)

- Corporate ESG performance exerts a significant positive effect on TFP, a finding that remains robust after controlling for endogeneity and conducting rigorous sensitivity tests. This indicates that ESG practices not only fulfill ethical and social responsibilities but also generate substantive economic benefits. The effect is particularly pronounced in the tertiary sector, SOEs, and firms with lower environmental risk.

- (2)

- ESG performance enhances TFP indirectly through three primary channels: capital, labor, and technology. Specifically, improved ESG performance helps alleviate financing constraints, enhance human capital, and stimulate innovation, thereby contributing to TFP growth.

- (3)

- can positively moderate the positive impact of corporate ESG performance on TFP. Mechanism tests reveal that environmental uncertainty exacerbates the negative effect of financing constraints on TFP, while enhancing the positive effects of human capital and technological innovation on TFP, thereby indirectly strengthening the overall positive influence of ESG performance on TFP.

6.2. Implications

- (1)

- Establishing a Cross-Industry ESG Practice Sharing Platform. To address the widespread challenges in ESG practices such as information barriers, redundant resource investment, and fragmented standards, internationally recognized industry associations and major standard-setting bodies (e.g., GRI, SASB, ISSB) should jointly take the lead in building a global, cross-industry ESG practice sharing platform. This platform should not merely serve as a website for information release, but rather evolve into a dynamic and collaborative innovation ecosystem. On one hand, it can collect and curate validated success cases from various industries worldwide. Each case will be deconstructed using a standardized template, clearly presenting its application background, concrete initiatives, resource inputs, challenges overcome, quantified benefits, and a return on investment (ROI) analysis. On the other hand, the platform can regularly publish common ESG-related technical bottlenecks across industries, and support targeted studies addressing real-world pain points—such as “the high cost of ESG implementation for SMEs” and “the difficulty of balancing short-term economic benefits with long-term sustainability goals.” By leveraging resource sharing and risk-sharing mechanisms, the platform can assist enterprises, particularly resource-constrained SMEs, in tackling the challenges of sustainable transformation.

- (2)

- Developing Differentiated Strategies. At present, enterprises of different industries and scales face heterogeneous challenges in advancing ESG strategies due to variations in resource endowment and risk-bearing capacity. These challenges include short-term cost pressures, technological renewal risks, and talent capability gaps. For enterprises in the primary sector, ecological restoration should be integrated into full life-cycle management, while exploring new development models that create a circular economy. At the same time, technological innovation should be leveraged to transform “costs” into “capital.” For instance, in the case of Zijin Mining, advanced wastewater treatment systems should go beyond compliance discharge standards and instead focus on water reuse and the recovery of valuable elements, thereby reducing production costs and achieving resource recycling. For enterprises in the secondary or tertiary sectors, it is necessary to establish robust risk management systems to address emerging risks such as cybersecurity threats, data leakage, and algorithmic failures. In addition, efforts should be made to improve yield rates and overall equipment efficiency, thereby reducing defective products and energy waste. ESG-related general knowledge and specialized skills training should also be provided to ensure that all employees understand the company’s ESG philosophy and its relevance to their individual work. For low-environmental-risk enterprises and SOEs, ESG should be fully integrated into the corporate vision, values, and long-term business strategies, with explicit articulation of ESG principles, priorities, and commitments. At the same time, ESG information should be included in routine disclosure, and information disclosure systems should be continuously improved. For high-environmental-risk enterprises and NSOEs, ESG performance can be embedded into supplier access criteria and performance evaluation systems to promote upstream joint emission reduction. Moreover, these enterprises can apply for green credit and issue SLBs, thereby linking financing costs with improvements in ESG performance to secure financial support and alleviate cost pressures. Finally, the government should act as a “precise facilitator” by designing a multi-level, differentiated policy toolbox that ensures all types of enterprises are “willing, capable, and adept” in fulfilling their ESG responsibilities, thereby achieving comprehensive improvements in TFP.

- (3)

- Enhancing ESG Management and Resilience Capacity. Research indicates that ESG performance exerts a significant positive impact on TFP, and that when firms fully leverage environmental uncertainty, this uncertainty can positively moderate the relationship between ESG performance and TFP. However, corporate ESG transformation is not an overnight process but rather a strategic investment. In the face of environmental uncertainty, systematic ESG planning and management can help firms transform short-term cost pressures into dynamic adaptive capabilities for coping with long-term uncertainties, thereby fostering sustainable competitiveness. First, firms should conduct a comprehensive “ESG materiality assessment” to identify ESG issues most closely related to their core business and those with the greatest long-term impact, prioritizing investment in these areas. This ensures that resources are concentrated in fields capable of creating the highest commercial and social value, alleviating the problem of strategic dispersion. Second, firms should adopt a phased investment approach by formulating a clear roadmap. They may begin with “low-cost, high-visibility” initiatives (e.g., office energy efficiency retrofits, employee volunteer programs) to quickly achieve results, build experience, and strengthen confidence, before gradually advancing to projects that require substantial investments. Finally, firms should enhance the capacity of existing financial, operational, and legal teams through in-service training, upgrading them into interdisciplinary talents proficient in both business and ESG. Compared with building new teams from scratch, this approach is more cost-effective and less resistant to implementation.

6.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, H.X.; Zhang, Z.H. The impact of managerial myopia on environmental, social and governance (ESG) engagement: Evidence from Chinese firms. Energy Econ. 2023, 122, 106705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taliento, M.; Favino, C.; Netti, A. Impact of Environmental, Social, and Governance Information on Economic Performance: Evidence of a Corporate ‘Sustainability Advantage’ from Europe. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amel-Zadeh, A.; Serafeim, G. Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financ. Anal. J. 2018, 74, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.P.; Yi, X.C.; Hu, K.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The effect of ESG performance on corporate green innovation. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2025, 31, 24–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chava, S.; Livdan, D.; Purnanandam, A. Do shareholder rights affect the cost of bank loans? Rev. Financ. Stud. 2009, 22, 2973–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.Y.; Li, Z.J.; Qiu, Z.X.; Wang, J.M.; Liu, B. ESG performance and corporate technology innovation: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2024, 206, 123520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.Y.; Wang, L.C.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Li, X.G.; Ao, T. Evaluation of Water-Energy-Food-Ecology System Development in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei Region from a Symbiotic Perspective and Analysis of Influencing Factors. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F.; Bosmans, P.; Leal, D.; Bisaria, S. Reforming Sustainability-Linked Bonds by Strengthening Investor Trust. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2024, 17, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitjean, M. Eco-friendly policies and financial performance: Was the financial crisis a game changer for large US companies? Energy Econ. 2019, 80, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Feng, G.F.; Yin, Z.J.; Chang, C.P. ESG disclosures, green innovation, and greenwashing: All for sustainable development? Sustain. Dev. 2024, 33, 1797–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.J.; Niu, J.J. Mitigating Greenwashing in Listed Companies: A Comprehensive Study on Strengthening Integrity in ESG Disclosure and Governance. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2021, 33, 6363–6372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathan, M.C.; Utz, S.; Dorfleitner, G.; Eckberg, J.; Chmel, L. What you see is not what you get: ESG scores and greenwashing risk. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 74, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMA. Market Integrity and Greenwashing Risks in Sustainable Finance—October 2023. International Capital Market Association. 2023. Available online: https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/Market-integrity-and-greenwashing-risks-in-sustainable-finance-October-2023.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Becker, M.G.; Martin, F.; Walter, A. The power of ESG transparency: The effect of the new SFDR sustainability labels on mutual funds and individual investors. Financ. Res. Lett. 2022, 47, 102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karwowski, M.; Raulinajtys-Grzybek, M. The application of corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions for mitigation of environmental, social, corporate governance (ESG) and reputational risk in integrated reports. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 28, 1270–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; You, J.L. The heterogeneous impacts of human capital on green total factor productivity: Regional diversity perspective. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 713562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillan, S.L.; Koch, A.; Starks, L.T. Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. J. Corp. Financ. 2021, 66, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Li, W.H.; Ren, X.H. More sustainable, more productive: Evidence from ESG ratings and total factor productivity among listed Chinese firms. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.H.; Ye, G.; Zhang, Y.X.; Mu, P.; Wang, H.X. Is the Chinese construction industry moving towards a knowledge- and technology-intensive industry? J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 259, 120964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.R.; Zhou, Y.L.; Wu, Y.H.; Ge, X.Y. The impact of green finance policy on total factor productivity: Based on quasi-natural experiment evidence from China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 425, 138873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.C.; Shen, Q. How does green credit policy affect total factor productivity at the corporate level in China: The mediating role of debt financing and the moderating role of financial mismatch. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 23237–23248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Hu, Y.Y.; Wu, Q.W. Subsidies and tax incentives-does it make a difference on TFP? Evidences from China’s photovoltaic and wind listed companies. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, H.L.; Wang, J. Index of financing constraints, intellectual capital, and total factor productivity in manufacturing enterprises: Evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 2025, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.L.; Sun, T.T.; Xu, R.Y. The impact of artificial intelligence on total factor productivity: Empirical evidence from China’s manufacturing enterprises. Econ. Change Restruct. 2023, 56, 1113–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.B.; Sun, J.W.; Liu, X.F.; Hu, Y.K. Digital transformation, innovation and total factor productivity in manufacturing enterprises. Financ. Res. Lett. 2025, 80, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuli, A.; Kostovetsky, L. Are red or blue companies more likely to go green? Politics and corporate social responsibility. J. Financ. Econ. 2014, 111, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.; Kashiramka, S. Impact of ESG disclosure on firm performance and cost of debt: Empirical evidence from India. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limkriangkrai, M.; Koh, S.; Durand, R.B. Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) profiles, stock returns, and financial policy: Australian evidence. Int. Rev. Financ. 2017, 17, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Tan, P.A.; Jeng, S.-Y.; Lin, C.-W.R.; Negash, Y.T.; Darsono, S.N.A.C. Sustainable Investment: Interrelated among Corporate Governance, Economic Performance and Market Risks Using Investor Preference Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sui, H.G.; Guo, T.R.; Sun, L.Y.; Islam, M.S. The impact of financing constraints on total factors productivity: Evidence from property law reform in China. Appl. Econ. 2023, 56, 7409–7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.J.; Guariglia, A. Internal financial constraints and firm productivity in China: Do liquidity and export behavior make a difference? J. Comp. Econ. 2013, 41, 1123–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.-W.; Choi, D. The Effects of ESG Management on Business Performance: The Case of Incheon International Airport. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, M.Y.; Luo, F.; Bu, Y. Green innovation and corporate financial performance: Insights from operating risks. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espahbodi, L.; Espahbodi, R.; Juma, N.; Westbrook, A. Sustainability priorities, corporate strategy, and investor behavior. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2019, 37, 149–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.H.; Yu, H.Y. Green innovation strategy and green innovation: The roles of green creativity and green organizational identity. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2018, 25, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.L.; Pang, S.L.; Hmani, I.; Hmani, I.; Li, C.F.; He, Z.X. Towards sustainable development: How does technological innovation drive the increase in green total factor productivity? Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Yang, C.H.; Liu, C. Economic policy uncertainty and corporate risk-taking: Loss aversion or opportunity expectations. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2021, 69, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Cheng, P.F.; Choi, B. Impact of corporate environmental uncertainty on environmental, social, and governance performance: The role of government, investors, and geopolitical risk. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, O. Environmental, social and governance reporting in China. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2014, 23, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Hu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Z.; Yang, G.; Sun, Z. Are Firms More Willing to Seek Green Technology Innovation in the Context of Economic Policy Uncertainty?—Evidence from China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.N.; Karia, N. How ESG Performance Promotes Organizational Resilience: The Role of Ambidextrous Innovation Capability and Digitalization. Bus. Strategy Dev. 2025, 8, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, D.I.; Chow, C.; Wu, A. The role of transformational leadership in enhancing organizational innovation: Hypotheses and some preliminary findings. Leadersh. Q. 2003, 14, 525–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M.A.; Tyler, B.B. Strategic decision-models—Integrating different perspectives. Strateg. Manag. J. 1991, 12, 327–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsohn, J.; Petrin, A. Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2003, 70, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.Y.; Jin, Y.F.; Zhang, C. ESG rating results and corporate total factor productivity. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 95, 103381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Shen, W.; Tan, Y.; Matac, L.M.; Samad, S. Environmental Uncertainty, Environmental Regulation and Enterprises’ Green Technological Innovation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Olsen, L. Environmental uncertainty and managers’ use of discretionary accruals. Account. Organ. Soc. 2009, 34, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Sun, Z.Y.; Wang, W.J.; Hua, Q.Y.; Wu, F.Z. The impact of environmental uncertainty on ESG performance: Emotional vs. rational. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 397, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Du, H.Y.; Yu, B. Corporate ESG performance and manager misconduct: Evidence from China. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2022, 82, 102201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.M.; Gao, D.; Sun, J. Does ESG performance promote total factor productivity? Evidence from China. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 1063736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, W.; Muller, T.; Rosenbach, D.; Salzmann, A. Corporate social responsibility, investor protection, and cost of equity: A cross-country comparison. J. Bank. Financ. 2018, 96, 34–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Notation | Variable Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | TFP | LP Estimator of TFP | |

| Independent Variable | ESG Performance | The average of quarterly ESG scores (across four quarters) provided by HuaZheng | |

| Mediating Variables | Financing constraints | KZ Index | |

| Human capital | Logarithm of (1 + number of employees with bachelor’s degree or higher) | ||

| Technological innovation | Logarithm of (1 + total utility model patent applications) | ||

| Moderating Variable | Environmental uncertainty | Employing the Ghosh and Olsen methodology for measurement | |

| Control Variables | Total assets | Total Assets | |

| Firm age | Current Year-Founding Year + 1 | ||

| Ownership concentration index | Top 10 Tradable Shareholders’ Ownership Percentage | ||

| Net profit | Total Profit (Current Year) | ||

| return on assets | (Net Income/Average Total Assets) × 100% | ||

| Inventory turnover ratio | (Cost of Goods Sold/Average Inventory) × 100% |

| Variable | Obs. | Mean | Median | Std. Dev. | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25,232 | 8.323 | 8.222 | 1.067 | 4.312 | 13.10 | |

| 25,232 | 4.105 | 4 | 1.062 | 1 | 8 | |

| 25,232 | 1.039 | 1.265 | 2.496 | −11.33 | 25.70 | |

| 25,232 | 6.103 | 5.996 | 1.331 | 0 | 12.39 | |

| 25,232 | 2.120 | 2.079 | 1.629 | 0 | 9.087 | |

| 25,232 | 0.285 | 0.151 | 0.475 | 0.000539 | 14.35 | |

| 25,232 | 17.21 | 3.851 | 79.50 | 0.0459 | 2733 | |

| 25,232 | 10.62 | 9 | 7.435 | 0 | 31 | |

| 25,232 | 58.04 | 58.81 | 15.11 | 8.779 | 101.0 | |

| 25,232 | 5.768 | 1.241 | 33.63 | −687.4 | 1460 | |

| 25,232 | 0.0495 | 0.0697 | 1.131 | −174.9 | 2.877 | |

| 25,232 | 3.282 | 0.0383 | 257.7 | −3.84 × 10−5 | 39,291 |

| (1) Without Control Variables and Without Robust Standard Errors | (2) With Control Variables but Without Robust Standard Errors | (3) With Control Variables and with Robust Standard Errors | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0527 *** | 0.0440 *** | 0.0440 *** | |

| (13.21) | (11.04) | (6.76) | |

| 0.000390 *** | 0.000390 | ||

| (3.88) | (0.91) | ||

| 0.0758 *** | 0.0758 *** | ||

| (18.87) | (13.83) | ||

| 0.00355 *** | 0.00355 *** | ||

| (9.68) | (3.75) | ||

| 0.00225 *** | 0.00225 *** | ||

| (13.25) | (3.97) | ||

| 0.00599 *** | 0.00599 | ||

| (2.58) | (0.68) | ||

| 0.0000386 *** | 0.0000386 *** | ||

| (3.73) | (5.74) | ||

| 7.597 *** | 7.042 *** | 7.042 *** | |

| (47.85) | (43.93) | (24.64) | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | |

| NO | NO | YES | |

| 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | |

| 0.172 | 0.186 | 0.299 |

| (1) Alternative Dependent Variables | (2) Alternative Independent Variables | (3) Excluding of Extreme Values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0540 *** | 0.0250 *** | 0.0427 *** | ||

| (7.57) | (4.33) | (6.69) | ||

| 0.00633 *** | ||||

| (3.65) | ||||

| 9.288 *** | 5.564 *** | 7.598 *** | 7.061 *** | |

| (32.79) | (20.38) | (28.48) | (25.96) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 25,232 | 25,232 | 8389 | 25,232 | |

| 0.360 | 0.298 | 0.326 | 0.308 | |

| (1) Lagged ESG (t − 1) | (2) 2SLS | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0268 *** | |||||

| (6.33) | |||||

| 0.726 *** | |||||

| (37.09) | |||||

| 5.06 × 10−10 *** | |||||

| (8.27) | |||||

| 0.0302 * | 0.806 *** | ||||

| (1.85) | (6.99) | ||||

| 6.837 *** | 1.092 *** | 7.276 *** | 4.347 *** | 4.063 *** | |

| (36.79) | (3.96) | (41.99) | (16.13) | (7.21) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 21,221 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 23,881 | 23,881 | |

| Industrial Classification | Ownership Type | Environmental Risk Characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Sector | Secondary Sector | Tertiary Sector | SOEs | NSOEs | High Environmental Risk | Low Environmental Risk | |

| −0.0368 | 0.0429 *** | 0.0522 *** | 0.0497 ** | 0.0463 *** | 0.0366 *** | 0.0426 *** | |

| (−0.83) | (6.33) | (3.20) | (2.39) | (6.72) | (3.64) | (5.38) | |

| 7.390 *** | 8.044 *** | 8.180 *** | 6.757 *** | 7.155 *** | 7.831 *** | 7.113 *** | |

| (21.07) | (23.51) | (26.68) | (16.88) | (24.65) | (20.95) | (25.92) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 297 | 19,065 | 5870 | 2626 | 22,606 | 6960 | 18,272 | |

| 0.259 | 0.333 | 0.174 | 0.389 | 0.300 | 0.320 | 0.301 | |

| (1) Capital Factors | (2) Labor Factors | (3) Technological Factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.226 *** | 0.0409 *** | 0.0707 *** | 0.0178 *** | 0.0863 *** | 0.0374 *** | |

| (−9.92) | (6.36) | (9.65) | (3.04) | (8.06) | (5.84) | |

| −0.0137 *** | ||||||

| (−4.20) | ||||||

| 0.370 *** | ||||||

| (22.07) | ||||||

| 0.0765 *** | ||||||

| (12.19) | ||||||

| 6.465 *** | 7.131 *** | 4.101 *** | 5.526 *** | 0.0855 *** | 0.0383 *** | |

| (7.34) | (24.23) | (11.81) | (27.37) | (8.01) | (5.99) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | |

| 0.142 | 0.302 | 0.318 | 0.412 | 0.225 | 0.314 | |

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0440 *** | 0.0472 *** | |

| (6.76) | (7.34) | |

| 0.127 *** | ||

| (6.21) | ||

| 0.0322 *** | ||

| (2.93) | ||

| 7.042 *** | 6.983 *** | |

| (24.64) | (24.37) | |

| YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | |

| 25,232 | 25,232 | |

| 0.299 | 0.305 |

| (1) Financial Constraints | (2) Human Capital | (3) Technological Innovation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −0.226 *** | −0.217 *** | 0.0452 *** | 0.0707 *** | 0.0716 *** | 0.0212 *** | 0.0863 *** | 0.0874 *** | 0.0427 *** | |

| (−9.92) | (−9.83) | (7.06) | (9.65) | (9.86) | (3.59) | (8.06) | (8.21) | (6.67) | |

| 0.0917 | 0.108 *** | 0.137 *** | 0.0661 *** | 0.0443 * | 0.120 *** | ||||

| (1.61) | (5.86) | (6.39) | (3.89) | (1.67) | (6.19) | ||||

| −0.0471 | 0.00126 | 0.0120 | |||||||

| (−1.14) | (0.65) | (0.88) | |||||||

| −0.0121 *** | |||||||||

| (−3.85) | |||||||||

| 0.360 *** | |||||||||

| (21.68) | |||||||||

| 0.0734 *** | |||||||||

| (12.10) | |||||||||

| −0.0171 *** | |||||||||

| (−3.67) | |||||||||

| 0.0301 *** | |||||||||

| (2.94) | |||||||||

| 0.0456 *** | |||||||||

| (4.99) | |||||||||

| 6.465 *** | 6.397 *** | 7.085 *** | 4.101 *** | 4.048 *** | 5.545 *** | 0.347 | 0.327 | 6.986 *** | |

| (7.34) | (7.19) | (23.96) | (11.81) | (11.70) | (26.56) | (0.86) | (0.80) | (23.05) | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | |

| 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | 25,232 | |

| 0.142 | 0.143 | 0.309 | 0.318 | 0.324 | 0.415 | 0.225 | 0.225 | 0.323 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, Z. The Impact of Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance on Total Factor Productivity: An Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198552

Li Y, Huang Y, Zhao Y, Ye Z. The Impact of Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance on Total Factor Productivity: An Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198552

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Yuan, Yongchun Huang, Yupeng Zhao, and Zi Ye. 2025. "The Impact of Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance on Total Factor Productivity: An Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198552

APA StyleLi, Y., Huang, Y., Zhao, Y., & Ye, Z. (2025). The Impact of Corporate Environmental, Social, and Governance Performance on Total Factor Productivity: An Analysis of the Moderating Effect of Environmental Uncertainty. Sustainability, 17(19), 8552. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198552