Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation Behaviour Model in a Touristic Coastal Destination—Pre and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. COVID-19 and Tourism

2.2. Motivation

2.3. Satisfaction

2.4. Recommendation

2.5. Relationship Among Tourist Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation

3. Materials and Methods

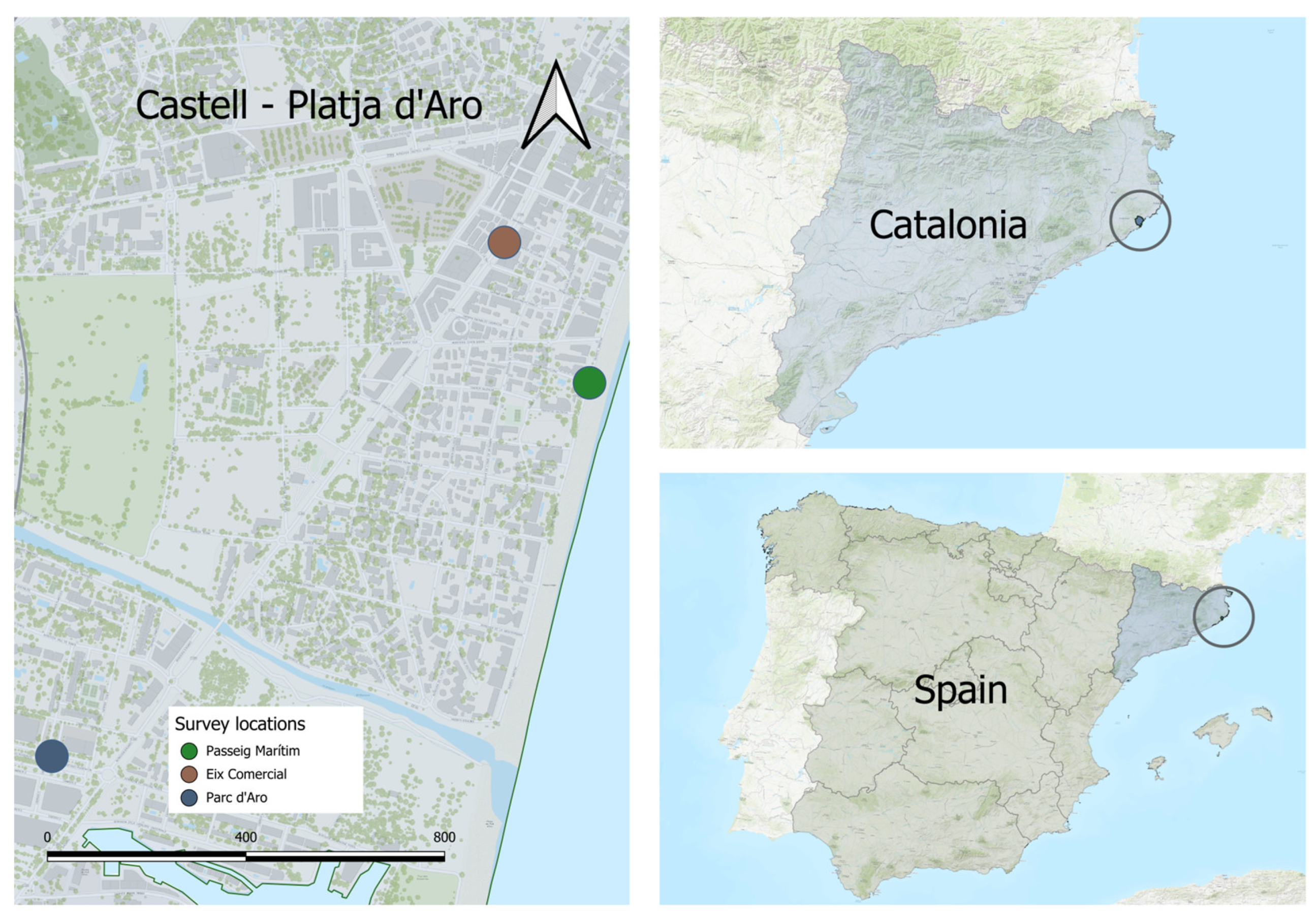

3.1. Tourist Destination

3.2. Questionnaire Design and Operationalisation

3.3. Sampling and Data Collection

3.4. Method

4. Results

4.1. Sample Description

4.2. Pre-COVID-19 Pandemic and Pandemic Models’ Comparison

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Practical Implications

5.2. Limitations of This Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J. Avoiding Panic during Pandemics: COVID-19 and Tourism-Related Businesses. Tour. Manag. 2021, 86, 104306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Tang, X. Tourism during Health Disasters: Exploring the Role of Health System Quality, Transport Infrastructure, and Environmental Expenditures in the Revival of the Global Tourism Industry. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Chiu, Y.; Tian, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, Q. Safety or Travel: Which Is More Important? The Impact of Disaster Events on Tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C. Theorising Tourism in Crisis: Writing and Relating in Place. Tour. Stud. 2021, 21, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Tourism Resilience in the ‘New Normal’: Beyond Jingle and Jangle Fallacies? J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 54, 513–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wen, L.; Liu, H.; Song, H. Predicting Tourism Recovery from COVID-19: A Time-Varying Perspective. Econ. Model. 2024, 135, 106706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Fernandez, M. Territorial Tourism Resilience in the COVID-19 Summer. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastegar, R.; Seyfi, S.; Shahi, T. Tourism SMEs’ Resilience Strategies amidst the COVID-19 Crisis: The Story of Survival. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2023, 2, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Vanneste, D.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F.; Farfán-Pacheco, K.; Rodriguez-Girón, S. Systematization Toward a Tourism Collaboration Network Grounded in Research-Based Learning. Lessons Learned from an International Project in Ecuador. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.D.; Thomas, A.; Paul, J. Reviving Tourism Industry Post-COVID-19: A Resilience-Based Framework. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 37, 100786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gössling, S. Pandemics, Transformations and Tourism: Be Careful What You Wish For. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranghieri, F.; Ishiwatari, M. (Eds.) Learning from Megadisasters: Lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4648-0153-2. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, B.W.; Jiang, Y. A Review of Research on Tourism Risk, Crisis and Disaster Management: Launching the Annals of Tourism Research Curated Collection on Tourism Risk, Crisis and Disaster Management. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shen, Y.; Choi, C. The Effects of Motivation, Satisfaction and Perceived Value on Tourist Recommendation. Travel Tour. Res. Assoc. Adv. Tour. Res. Glob. 2015, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Prayag, G.; Hosany, S.; Muskat, B.; Del Chiappa, G. Understanding the Relationships between Tourists’ Emotional Experiences, Perceived Overall Image, Satisfaction, and Intention to Recommend. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, N.M.; Ribeiro, M.A.; Prayag, G. Psychological Determinants of Tourist Satisfaction and Destination Loyalty: The Influence of Perceived Overcrowding and Overtourism. J. Travel Res. 2023, 62, 644–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-H.; Wang, W.-C. Impacts of Climate Change Knowledge on Coastal Tourists’ Destination Decision-Making and Revisit Intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2023, 56, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, B.; Ong, Y.; Ito, N. How Trust in a Destination’s Risk Regulation Navigates Outbound Travel Constraints on Revisit Intention Post-COVID-19: Segmenting Insights from Experienced Chinese Tourists to Japan. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2022, 25, 100711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Luo, J.M. Relationship among Travel Motivation, Satisfaction and Revisit Intention of Skiers: A Case Study on the Tourists of Urumqi Silk Road Ski Resort. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, T.; Caber, M. Examining the Relationship between Tourist Motivation and Satisfaction by Two Competing Methods. Tour. Manag. 2018, 69, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzel, Ö.; Sahin, I.; Ryan, C. Push-Motivation-Based Emotional Arousal: A Research Study in a Coastal Destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniya, R.; Paudel, K. An Analysis of Push and Pull Travel Motivations of Domestic Tourists in Nepal. J. Manag. Dev. Stud. 2016, 27, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orden-Mejía, M.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Sociodemographic Aspects and Satisfaction of Chinese Tourists Visiting a Coastal City. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D.; Gyimóthy, S. The COVID-19 Crisis as an Opportunity for Escaping the Unsustainable Global Tourism Path. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, H.; Acharjee, M.R.; Talukder, A. Tourism Index Evaluation of Exposed Coast, Bangladesh: A Modeling Approach. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shampa, M.T.A.; Shimu, N.J.; Chowdhury, K.M.A.; Islam, M.M.; Ahmed, M.K. A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Coastal Zone Management in Bangladesh: Present Status and the Way Forward. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo Vila, N.; Fraiz Brea, J.A.; de Carlos, P. Film Tourism in Spain: Destination Awareness and Visit Motivation as Determinants to Visit Places Seen in TV Series. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2021, 27, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.-S.; Lee, C.-K.; Olya, H. Hocance Tourism Motivations: Scale Development and Validation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 114009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horne, L.; DiMatteo-LePape, A.; Wolf-Gonzalez, G.; Briones, V.; Soucy, A.; De Urioste-Stone, S. Climate Change Planning in a Coastal Tourism Destination, A Participatory Approach. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2022, 23, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Niazi, M.A.K. Understanding Environmentally Responsible Behavior of Tourists at Coastal Tourist Destinations. Soc. Responsib. J. 2023, 19, 1952–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Tourism Organization 2020: The Worst Year in the History of Tourism, with One Billion Fewer International Arrivals. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/2020-worst-year-in-tourism-history-with-1-billion-fewer-international-arrivals (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Zhang, H.; Qiu, R.T.R.; Wen, L.; Song, H.; Liu, C. Has COVID-19 Changed Tourist Destination Choice? Ann. Tour. Res. 2023, 103, 103680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, L.; Khalid, U.; Gopalan, S. COVID-19 Economic Policy Response, Resilience and Tourism Recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. Empir. Insights 2022, 3, 100073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. A Longitudinal Analysis of the Effects of COVID-19 on Tourists’ Health Risk Perceptions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 357, 117230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, Y.; Çayırağası, F.; Çopuroğlu, F. The Mediating Role of Destination Satisfaction between the Perception of Gastronomy Tourism and Consumer Behavior during COVID-19. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 28, 100525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.K.P.; Li, X.; Lau, V.M.C.; Dioko, L. Destination Governance in Times of Crisis and the Role of Public-Private Partnerships in Tourism Recovery from Covid-19: The Case of Macao. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2022, 51, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepez, C.; Leimgruber, W. The Evolving Landscape of Tourism, Travel, and Global Trade since the Covid-19 Pandemic. Res. Glob. 2024, 8, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayih, B.E.; Singh, A. Modeling Domestic Tourism: Motivations, Satisfaction and Tourist Behavioral Intentions. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodness, D. Measuring Tourist Motivation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 555–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.d.L.; Anjos, F.A.d.; Añaña, E.d.S.; Weismayer, C. Modelling the Overall Image of Coastal Tourism Destinations through Personal Values of Tourists: A Robust Regression Approach. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 35, 100412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, A.; Kozak, M.; Ferradeira, J. From Tourist Motivations to Tourist Satisfaction. Int. J. Cult. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2013, 7, 411–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acha-Anyi, P.N.; Nomnga, V.J. Visitor Motivations and Use of Information Communication Technology at a Coastal Destination: The Case of Limbe—Cameroon. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2384188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieger, P.; Prayag, G.; Bruwer, J. ‘Pull’ Motivation: An Activity-Based Typology of International Visitors to New Zealand. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 173–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Tkaczynski, A. Does the Destination Matter in Domestic Tourism? Ann. Tour. Res. 2024, 108, 103817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otoo, F.E.; Kim, S.; King, B. African Diaspora Tourism—How Motivations Shape Experiences. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Coromina, L. Social Impacts in a Coastal Tourism Destination: “Effects of COVID-19 Pandemic”. J. Mar. Isl. Cult. 2024, 13, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, E.; Kim, H.; Uysal, M. Life Satisfaction and Support for Tourism Development. Ann. Tour. Res. 2015, 50, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chan, S. A New Nature-Based Tourism Motivation Model: Testing the Moderating Effects of the Push Motivation. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 18, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orams, M.; Lück, M. Coastal Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism; Jafari, J., Xiao, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 157–158. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, Y.; Uysal, M. An Examination of the Effects of Motivation and Satisfaction on Destination Loyalty: A Structural Model. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutra, C.; Karyopouli, S. Cyprus’ Image—A Sun and Sea Destination—As a Detrimental Factor to Seasonal Fluctuations. Exploration into Motivational Factors for Holidaying in Cyprus. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2013, 30, 700–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, P.; Pickering, C.M. Analysing Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Tourism and Tourists’ Satisfaction in Nepal Using Social Media. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2023, 44, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regalado-Pezúa, O.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Carvache-Franco, W. Perceived Value and Its Relationship to Satisfaction and Loyalty in Cultural Coastal Destinations: A Study in Huanchaco, Peru. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, 0286923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutanga, C.N.; Vengesayi, S.; Chikuta, O.; Muboko, N.; Gandiwa, E. Travel Motivation and Tourist Satisfaction with Wildlife Tourism Experiences in Gonarezhou and Matusadona National Parks, Zimbabwe. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2017, 20, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savinovic, A.; Kim, S.; Long, P. Audience Members’ Motivation, Satisfaction, and Intention to Re-Visit an Ethnic Minority Cultural Festival. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pestana, M.H.; Parreira, A.; Moutinho, L. Motivations, Emotions and Satisfaction: The Keys to a Tourism Destination Choice. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Hassan, T.; Carvache-Franco, O. The Cognitive and Conative Image in Insular Marine Protected Areas: A Study from Galapagos, Ecuador. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2024, 47, 100793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, L.D.; Tuu, H.H.; Cong, L.C. The Effect of Social Media Marketing on Tourist Loyalty: A Mediation—Moderation Analysis in the Tourism Sector under the Stimulus-Organism-Response Model. J. Tour. Serv. 2024, 15, 294–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Hernández-Lara, A.B. Motivation and Segmentation of the Demand for Coastal and Marine Destinations. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 34, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The Tourist Gaze; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Urry, J.; Larsen, J. The Tourist Gaze 3.0, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 9781849203777. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, G.; Xu, B.; Lu, F.; Lu, Y. The Promotion Strategies and Dynamic Evaluation Model of Exhibition-Driven Sustainable Tourism Based on Previous/Prospective Tourist Satisfaction after COVID-19. Eval. Program. Plann 2023, 101, 102355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Víquez-Paniagua, A.G. Gastronomic Marketing Applied to Motivations and Satisfaction. In Proceedings of the 22nd LACCEI International Multi-Conference for Engineering, Education and Technology, San Jose, Costa Rica, 17–19 July 2024; Latin American and Caribbean Consortium of Engineering Institutions: Boca Raton, FA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.L.; Tran, P.T.K.; Tran, V.T. Destination Perceived Quality, Tourist Satisfaction and Word-of-Mouth. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 392–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, M.M.; Mim, M.K.; Hossain, A.; Khan, M.Y.H. Investigation of The Impact of Extended Marketing Mix and Subjective Norms on Visitors’ Revisit Intention: A Case of Beach Tourism Destinations. Gastroia: J. Gastron. Travel Res. 2023, 7, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Solis-Radilla, M.M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Carvache-Franco, O. The Cognitive Image and Behavioral Loyalty of A Coastal and Marine Destination: A Study in Acapulco, Mexico. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 24, 146–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Rojas, C.; González Hernández, M.; León, C.J. Segmented Importance-Performance Analysis in Whale-Watching: Reconciling Ocean Coastal Tourism with Whale Preservation. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2023, 233, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C. Perceived Risk and Destination Knowledge in the Satisfaction-Loyalty Intention Relationship: An Empirical Study of European Tourists in Vietnam. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2021, 33, 100343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwanitdumrong, K.; Chen, C.-L. Investigating Factors Influencing Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior with Extended Theory of Planned Behavior for Coastal Tourism in Thailand. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.F.; Elrick-Barr, C.E.; Thomsen, D.C.; Celliers, L.; Le Tissier, M. Impacts of Tourism on Coastal Areas. Camb. Prism. Coast. Futures 2023, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agius, K.; Baldacchino, G. What’s in a Name? The Impact of Disasters on Islands’ Reputations: The Cases of Giglio and Ustica. Shima 2022, 16, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising Tourism for Social and Ecological Justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Olya, H.G.T.; Maleki, P.; Dalir, S. Behavioral Responses of 3S Tourism Visitors: Evidence from a Mediterranean Island Destination. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. The “War over Tourism”: Challenges to Sustainable Tourism in the Tourism Academy after COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, J.; Jang, S.; Zhao, Y. Understanding Tourists’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior at Coastal Tourism Destinations. Mar. Policy 2022, 143, 105178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestanza-Ramón, C.; Sanchez Capa, M.; Figueroa Saavedra, H.; Rojas Paredes, J. Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Continental Ecuador and Galapagos Islands: Challenges and Opportunities in a Changing Tourism and Economic Context. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Qi, H. Exploring Tourist Experience of Island Tourism Based on Text Mining: A Case Study of Jiangmen, China. SHS Web Conf. 2023, 170, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, L.C. A Formative Model of the Relationship between Destination Quality, Tourist Satisfaction and Intentional Loyalty: An Empirical Test in Vietnam. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2016, 26, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll-de-Alba, J.; Prats, L.; Coromina, L. Differences between Short and Long Break Tourists in Urban Destinations: The Case of Barcelona. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 14, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S.; Uysal, M. Market Segments of Push and Pull Motivations: A Canonical Correlation Approach. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 1996, 8, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prebensen, N.; Skallerud, K.; Chen, J.S. Tourist Motivation with Sun and Sand Destinations: Satisfaction and the Wom-Effect. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2010, 27, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Báez-Montenegro, A.; Centeno, A.B.; Lara, J.Á.S.; Prieto, L.C.H. Contingent Valuation and Motivation Analysis of Tourist Routes: Application to the Cultural Heritage of Valdivia (Chile). Tour. Econ. 2015, 22, 558–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y. Travel Motivation, Destination Image and Visitor Satisfaction of International Tourists After the 2008 Wenchuan Earthquake: A Structural Modelling Approach. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1260–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saayman, M.; Slabbert, E.; Van Der Merwe, P. Travel Motivation: A Tale of Two Marine Destinations in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Res. Sport Phys. Educ. Recreat. 2009, 31, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira da Silva, M.; Martins, F.; Costa, C.; Pita, C. Visitors’ Experience in a Coastal Heritage Context: A Segmentation Analysis and Its Influence on in Situ Destination Image and Loyalty. Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2024, 37, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M.; Ivkov, M.; Kim, S.S. Destination Loyalty Explained through Place Attachment, Destination Familiarity and Destination Image. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 22, 604–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramón-Cardona, J.; Álvarez-Bassi, D.; Sánchez-Fernández, M.D. Residents’ Attitudes towards Nightlife Supply: A Comparison of Ibiza (Spain) and Punta Del Este (Uruguay). Eur. J. Tour. Res. 2021, 29, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, S. Examining Relationships between Destination Image, Tourist Motivation, Satisfaction, and Visit Intention in Yogyakarta—Expert Journal of Business and Management. Expert. J. Bus. Manag. 2019, 7, 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Idescat (Institut d’Estadística de Catalunya). Castell d’Aro, Platja d’Aro i s’Agaró. Available online: https://www.idescat.cat/emex/?id=170486 (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Ajuntament de Castell d’Aro, P. d’Aro i S. Presentació Del Municipi. Available online: https://ciutada.platjadaro.com/ (accessed on 10 February 2025).

- Jeong, Y.; Kim, S. A Study of Event Quality, Destination Image, Perceived Value, Tourist Satisfaction, and Destination Loyalty among Sport Tourists. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2020, 32, 940–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariel, G.; Davidov, E. Assessment of Measurement Equivalence with Cross-National and Longitudinal Surveys in Political Science. Eur. Political Sci. 2012, 11, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, W. Measurement Invariance, Factor Analysis and Factorial Invariance. Psychometrika 1993, 58, 525–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.-B.E.M.; Baumgartner, H. Assessing Measurement Invariance in Cross-National Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 25, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieciuch, J.; Davidov, E.; Vecchione, M.; Beierlein, C.; Schwartz, S.H. The Cross-National Invariance Properties of a New Scale to Measure 19 Basic Human Values: A Test Across Eight Countries. J. Cross Cult. Psychol. 2014, 45, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidov, E.; Meuleman, B.; Cieciuch, J.; Schmidt, P.; Billiet, J. Measurement Equivalence in Cross-National Research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L.; Muthén, B. (Eds.) Mplus User’s Guide, 8th ed.; Muthén & Muthén: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indices to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2007, 14, 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncu, H.; Kamasak, R. Post-Pandemic Shifts in Travel Habits: New Trends and Strategies. In Reference Module in Social Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dann, G.M.S. Tourist Motivation an Appraisal. Ann. Tour. Res. 1981, 8, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotiadis, A.; Polyzos, S.; Huan, T.C.T.C. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly on COVID-19 Tourism Recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Tourism Organization International Tourist Arrivals Grew 5% in Q1 2025. Available online: https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourist-arrivals-grew-5-in-q1-2025 (accessed on 22 July 2025).

| 2019 (n = 394) | (%) | 2020 (n = 468) | (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Man | 190 | 48.2 | 255 | 54.5 |

| Woman | 204 | 51.8 | 213 | 45.5 |

| Total | 394 | 100.0 | 468 | 100.0 |

| Age | ||||

| 24 or less | 53 | 13.9 | 119 | 25.6 |

| 25–34 years | 74 | 19.5 | 95 | 20.5 |

| 35–44 years | 99 | 26.1 | 92 | 19.8 |

| 45–54 years | 92 | 24.2 | 82 | 17.7 |

| 55–64 years | 39 | 10.3 | 46 | 9.9 |

| 65 and over | 23 | 6.1 | 30 | 9.5 |

| Total | 380 | 100.0 | 464 | 100.0 |

| Min | 16 | 16 | ||

| Max | 80 | 81 | ||

| Average | 41 | 38.1 | ||

| SD | 13.5 | 15.4 | ||

| Origin | ||||

| Catalonia | 169 | 43.4 | 262 | 57.7 |

| France | 86 | 22.1 | 72 | 15.9 |

| Rest of Spain | 30 | 7.7 | 37 | 8.1 |

| Netherlands | 30 | 7.7 | 22 | 4.8 |

| UK | 16 | 4.1 | 11 | 2.2 |

| Belgium | 14 | 3.6 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Germany | 11 | 2.8 | 12 | 2.6 |

| Russia | 10 | 2.6 | 15 | 3.3 |

| Rest of Europe | 11 | 2.8 | 20 | 2.2 |

| Rest of the world | 12 | 3.1 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Total | 389 | 100.0 | 454 | 100.0 |

| Factor | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motivations | |||

| 1. To enjoy sun and beach | Pull | 93.6% | 86.6% |

| 2. To do water activities | Push | 58.8% | 76.2% |

| 3. To do sport activities | Push | 48.6% | 62.8% |

| 4. To enjoy gastronomy | Push | 48.8% | 74.5% |

| 5. To discover new places | Push | 44.5% | 72.3% |

| 6. To explore heritage | Push | 35.5% | 67.2% |

| 7. Good value for money | Pull | 34.5% | 76.8% |

| 8. To take a rest and relax | Push | 73.9% | 80.6% |

| 9. To enjoy nature | Push | 63.4% | 74.7% |

| 10. To enjoy shopping | Push | 50.4% | 70.4% |

| Satisfaction | |||

| I am pleased with my decision | 4.51 | 4.04 | |

| The place satisfies my expectations | 4.61 | 4.07 | |

| Recommendation | |||

| Recommendation to friends and relatives | 8.48 | 7.80 |

| χ2 | df. | P | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric Invariance | |||||||

| Model 1. To enjoy sun and beach | 7.700 | 6 | 0.261 | 0.996 | 0.992 | 0.026 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.071) | 0.024 |

| Model 2. To do water activities | 20.521 | 6 | 0.002 | 0.969 | 0.938 | 0.075 (CI 90%: 0.041, 0.104) | 0.034 |

| Model 3. To do sport activities | 18.107 | 6 | 0.006 | 0.975 | 0.950 | 0.068 (CI 90%: 0.034, 0.106) | 0.036 |

| Model 4. To enjoy gastronomy | 9.046 | 6 | 0.171 | 0.993 | 0.987 | 0.034 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.058) | 0.031 |

| Model 5. To discover new places | 9.815 | 6 | 0.133 | 0.992 | 0.983 | 0.038 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.080) | 0.032 |

| Model 6. To explore heritage | 13.428 | 6 | 0.037 | 0.984 | 0.968 | 0.054 (CI 90%: 0.013, 0.093) | 0.031 |

| Model 7. Good value for money | 11.747 | 6 | 0.068 | 0.988 | 0.976 | 0.047 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.087) | 0.036 |

| Model 8. To take a rest and relax | 5.597 | 6 | 0.470 | 0.999 | 0.999 | 0.000 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.060) | 0.002 |

| Model 9. To enjoy nature | 6.876 | 6 | 0.332 | 0.998 | 0.996 | 0.018 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.067) | 0.021 |

| Model 10. To enjoy shopping | 11.199 | 6 | 0.082 | 0.989 | 0.978 | 0.045 (CI 90%: 0.000, 0.085) | 0.028 |

| (a) Motivation → Satisfaction (Hypothesis H1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 (H1a) | 2020 (H1b) | Sig. Effect | |

| Model 1. To enjoy sun and beach | 0.323 ** | 0.502 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 2. To do water activities | 0.281 *** | 0.139 | 2019 |

| Model 3. To do sport activities | 0.062 | 0.341 *** | 2020 |

| Model 4. To enjoy gastronomy | 0.068 | 0.174 | - |

| Model 5. To discover new places | 0.156 ** | 0.180 | 2019 |

| Model 6. To explore heritage | 0.103 | 0.160 | - |

| Model 7. Good value for money | 0.377 *** | 0.207 | 2019 |

| Model 8. To take a rest and relax | 0.256 ** | 0.261 * | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 9. To enjoy nature | 0.175 ** | 0.395 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 10. To enjoy shopping | 0.182 ** | 0.362 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| (b) Satisfaction→recommendation (Hypothesis H2) | |||

| 2019 (H2a) | 2020 (H2b) | Sig. Effect | |

| Model 1. To enjoy sun and beach | 1.100 *** | 0.873 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 2. To do water activities | 1.103 *** | 0.846 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 3. To do sport activities | 1.105 *** | 0.860 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 4. To enjoy gastronomy | 1.106 *** | 0.869 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 5. To discover new places | 1.106 *** | 0.860 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 6. To explore heritage | 1.104 *** | 0.860 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 7. Good value for money | 1.109 *** | 0.850 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 8. To take a rest and relax | 1.101 *** | 0.864 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 9. To enjoy nature | 1.101 *** | 0.869 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

| Model 10. To enjoy shopping | 1.099 *** | 0.859 *** | 2019 and 2020 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alvarado-Vanegas, B.; Coromina, L.; Espinoza-Figueroa, F. Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation Behaviour Model in a Touristic Coastal Destination—Pre and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198520

Alvarado-Vanegas B, Coromina L, Espinoza-Figueroa F. Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation Behaviour Model in a Touristic Coastal Destination—Pre and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared. Sustainability. 2025; 17(19):8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198520

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlvarado-Vanegas, Byron, Lluís Coromina, and Freddy Espinoza-Figueroa. 2025. "Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation Behaviour Model in a Touristic Coastal Destination—Pre and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared" Sustainability 17, no. 19: 8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198520

APA StyleAlvarado-Vanegas, B., Coromina, L., & Espinoza-Figueroa, F. (2025). Motivation, Satisfaction and Recommendation Behaviour Model in a Touristic Coastal Destination—Pre and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Compared. Sustainability, 17(19), 8520. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17198520