From Crisis to Resilience: A Bibliometric Analysis of Food Security and Sustainability Amid Geopolitical Challenges

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

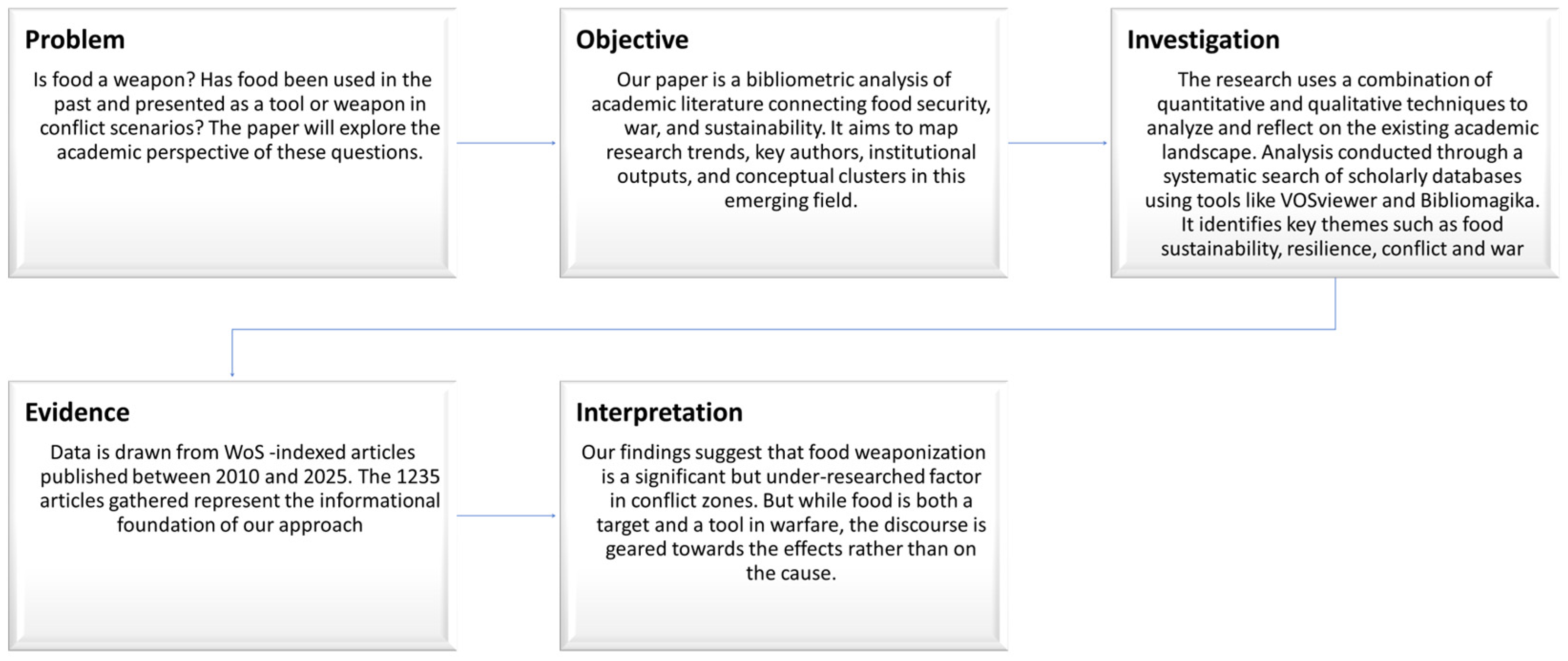

2.1. Study Design and Approach

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Search Strategy

- The first level addressed food security as a main topic for the research, with connected words like “hunger/malnutrition/nutrition/…” etc., because we are thinking about “Food security” as it has been defined in the 2024 Global Report on Food Crises [18]: “(…) All people, at all times, have physical, social, and economic access to sufficient, safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (…)”.

- The second level refers to the context of conflict and systems frailty with search terms like “conflict, fragility, violence, war, “humanitarian crisis”, displacement, “fragile settings”, “armed conflict”, “post-conflict” or “war zones”, necessary for understanding the context of food insecurity caused by the conflict setting, not referring to peacetime food insecurity.

- The third level addresses the solutions proposed across different research articles. Whether these involve policy recommendations, research and development initiatives, strategic approaches, or innovations, we aimed to identify the types of solutions put forward by our peers and assess whether there is a consistent, systemic direction or if the proposed measures are more context-specific and locally adapted.

2.4. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.5. Data Cleaning and Preparation

2.6. Tools

- -

- Zotero—A well-known reference management software used to collect, organize, and manage bibliographic data. Zotero facilitated the systematic collection of publications, ensured consistent citation formatting, and supported the export of metadata required for bibliometric analysis.

- -

- Excel—Used for data cleaning, sorting, and preliminary descriptive analysis. Excel allowed us to manually inspect the metadata, identify inconsistencies, and generate basic statistical summaries

- -

- Bibliomagika—A bibliometric Excel-based software employed to automatically clean, structure, and extract metadata from large publication datasets. Bibliomagika [43] was particularly useful in processing CSV files, standardizing author and keyword fields, and preparing the data for our chosen visualization tool.

- -

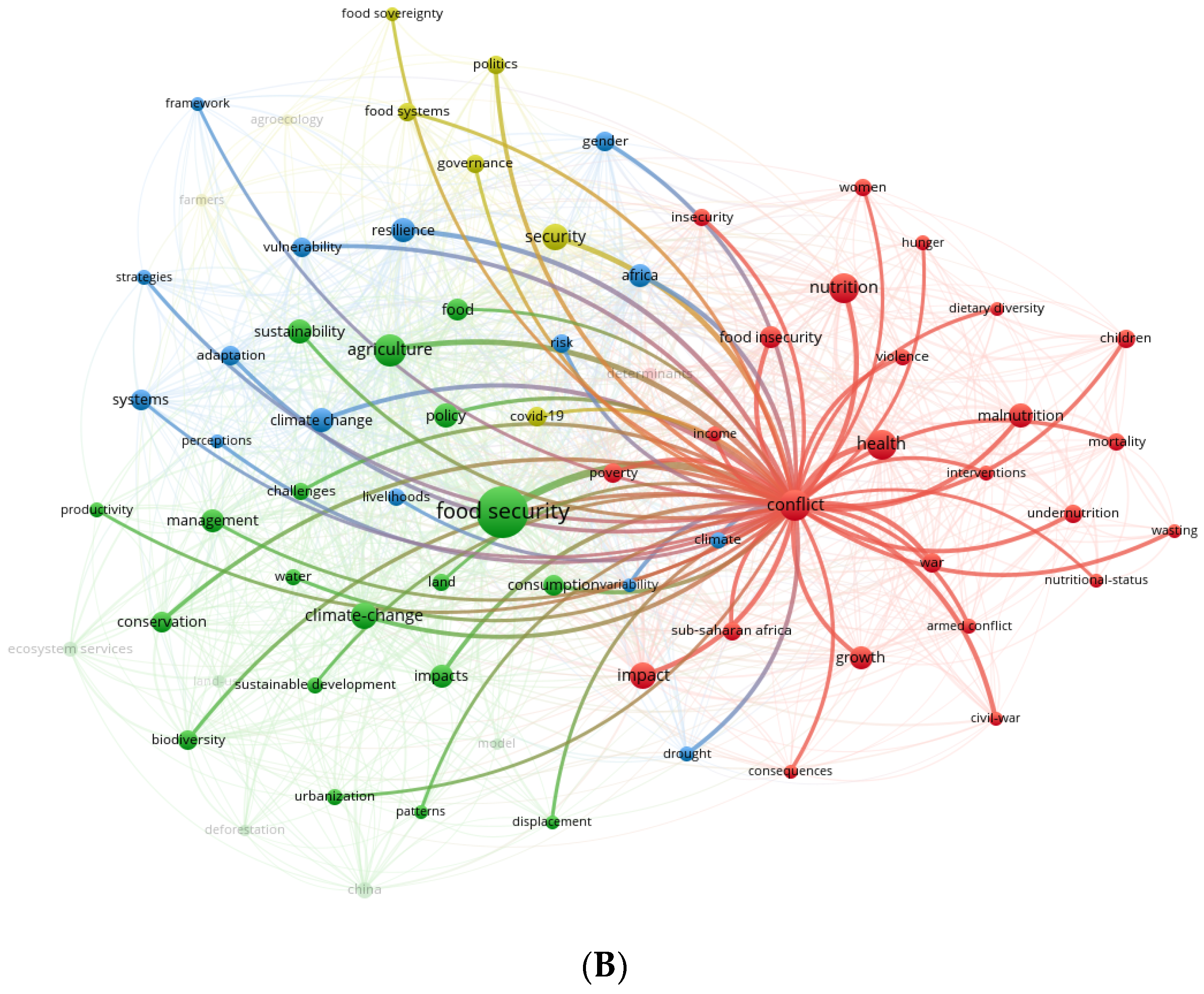

- VOSviewer—A specialized bibliometric visualization tool used to map co-authorship networks, keyword co-occurrence, and citation relationships. VOSviewer enabled us to visually explore the intellectual structure and thematic clusters within the literature.

2.7. Limitations

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. How Has Scholarly Understanding of the Role of Food in Geopolitical Contexts Evolved Since 2010, and How Is It Connected to Broader Crisis-Related Actions?

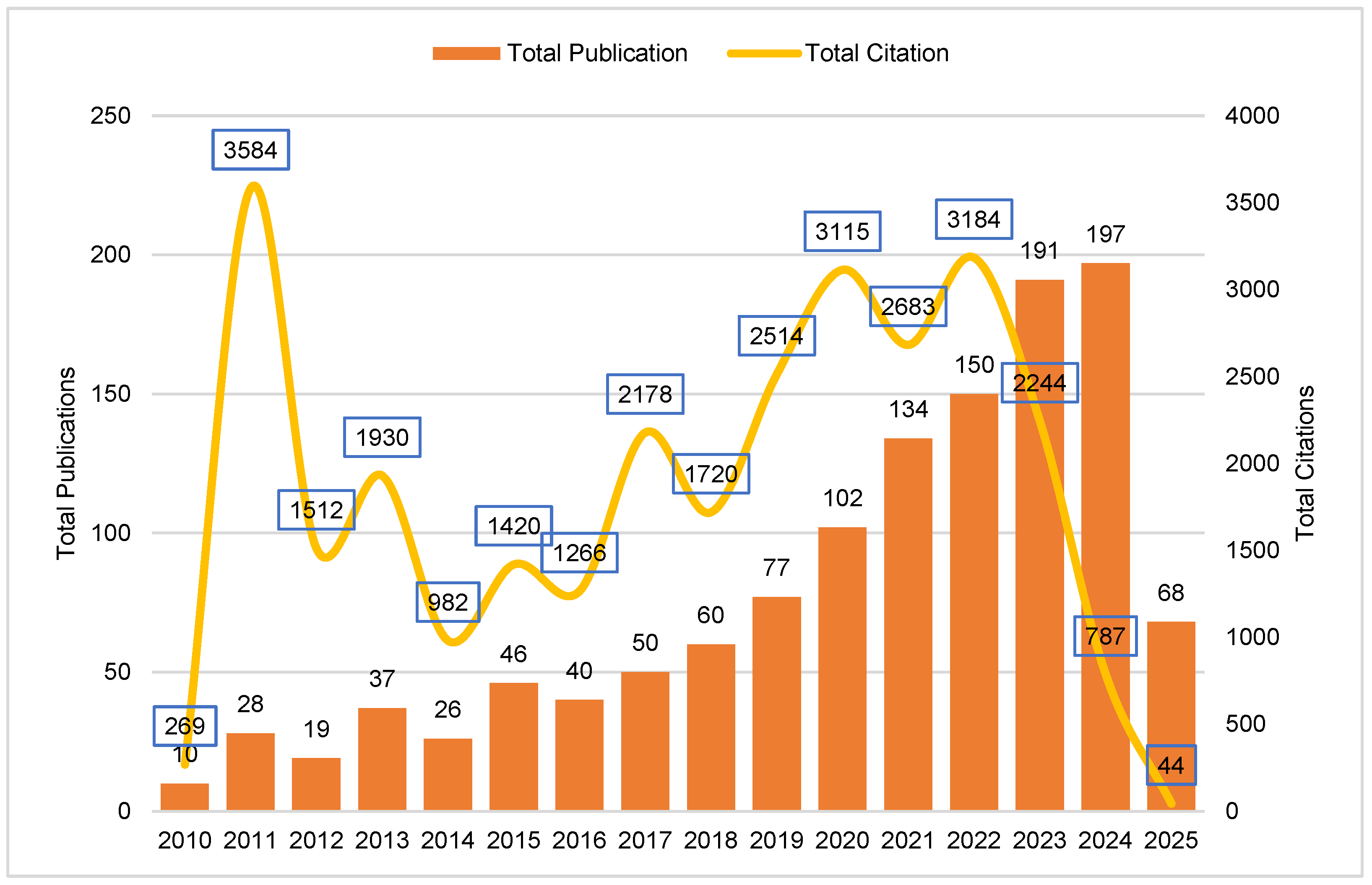

- 2011–2013: A slight uptick corresponds with global food price spikes and the Arab Spring, which included countries like Syria, Gaza and Iraq [44,45,46]. Many papers focus on the nutritional status and challenges faced by specific groups, particularly women and children in regions like India, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of Congo or Uganda. These studies examine undernutrition, maternal autonomy in feeding practices, and fluctuations in child wasting, highlighting health disparities in fragile or resource-limited settings [47,48,49].

- 2014–2019: A steady rise in papers tracks the long-lasting Syrian civil war, Yemen conflict, and South Sudan famine. Concepts like “weaponization of food” enter the discourse of the UN and WFP. FAO and different NGOs sounded alarms on siege tactics, causing famine. A large number of papers explore the impact of conflict on food security, particularly in countries like Yemen, Nigeria, Somalia, and Gaza. These studies focus on malnutrition, displacement, humanitarian responses, and the structural vulnerabilities exposed during crises. Papers such as “Acute malnutrition among children, mortality, and humanitarian interventions in conflict-affected regions—Nigeria [50] and “The effects of violent conflict on household resilience and food security: Evidence from the 2014 Gaza conflict” [51] underscore the deep entanglement of war, hunger, and systemic fragility. The adoption of UNSC Resolution 2417 in 2018 [23]—explicitly linking conflict and hunger—may have further catalyzed academic inquiry, as indicated by a jump in publications around 2019.

- 2020–2021: The literature expands rapidly, as a natural response to a growing international interest in the topic, and high-impact papers published in this period addressed how climate change exacerbates conflict risks and undermines crop yields. By 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic became another focus: publications emerged on how conflict-affected states coped with pandemic-related supply disruptions. Our data show “COVID-19” rapidly became a top keyword, reflecting concern that pandemic lockdowns and economic shocks could intensify food insecurity in fragile settings [52,53,54].

- 2022–2023: A significant event during this period is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. The war’s global fallout on food supplies prompted a flurry of research and commentary, from analyses of Black Sea grain exports to broader discussions of food as a geopolitical tool. In 2022 alone, at least 150 publications appeared, including highly cited pieces on the war’s impact on global food security [55,56]. 2023 also sustained high academic output, examining ongoing crises (e.g., drought and conflict in the Horn of Africa, instability in Haiti, and the Sahel). Topics widely range from child malnutrition [57,58] to the mental health impact of hunger in fragile settings [59].

- 2024–2025 (partial): While our data for 2025 is incomplete (covering early-year publications up to June), the trajectory suggests continued high engagement. Themes like food systems resilience, climate adaptation, and humanitarian response in conflict zones remain prominent. We also see emergent topics (e.g., the food security implications of the Gaza conflict and sanctions regimes). In these last 2 years, studies span food availability, household coping mechanisms, malnutrition, famine monitoring, and humanitarian assistance evaluation. Papers like “Dying of starvation if not from bombs: assessing measurement properties of the Food Insecurity Experiences Scale (FIES) in Gaza’s civilian population experiencing the world’s worst hunger crisis” and “Food insecurity and coping strategies in war-affected urban settings of Tigray” [60,61] capture the deadly convergence of violence and hunger while others assess conflict-specific food aid efficiency, nutrition for displaced populations, or post-war agricultural reconstruction (e.g., Ukraine, Colombia, Syria) [61,62,63,64,65] Notably, some 2023–2024 works are already influential—for instance, a Foreign Affairs analysis by Helder et al. (2023) calling food weaponization an “ancient tactic making a deadly comeback” has garnered policy attention [22].

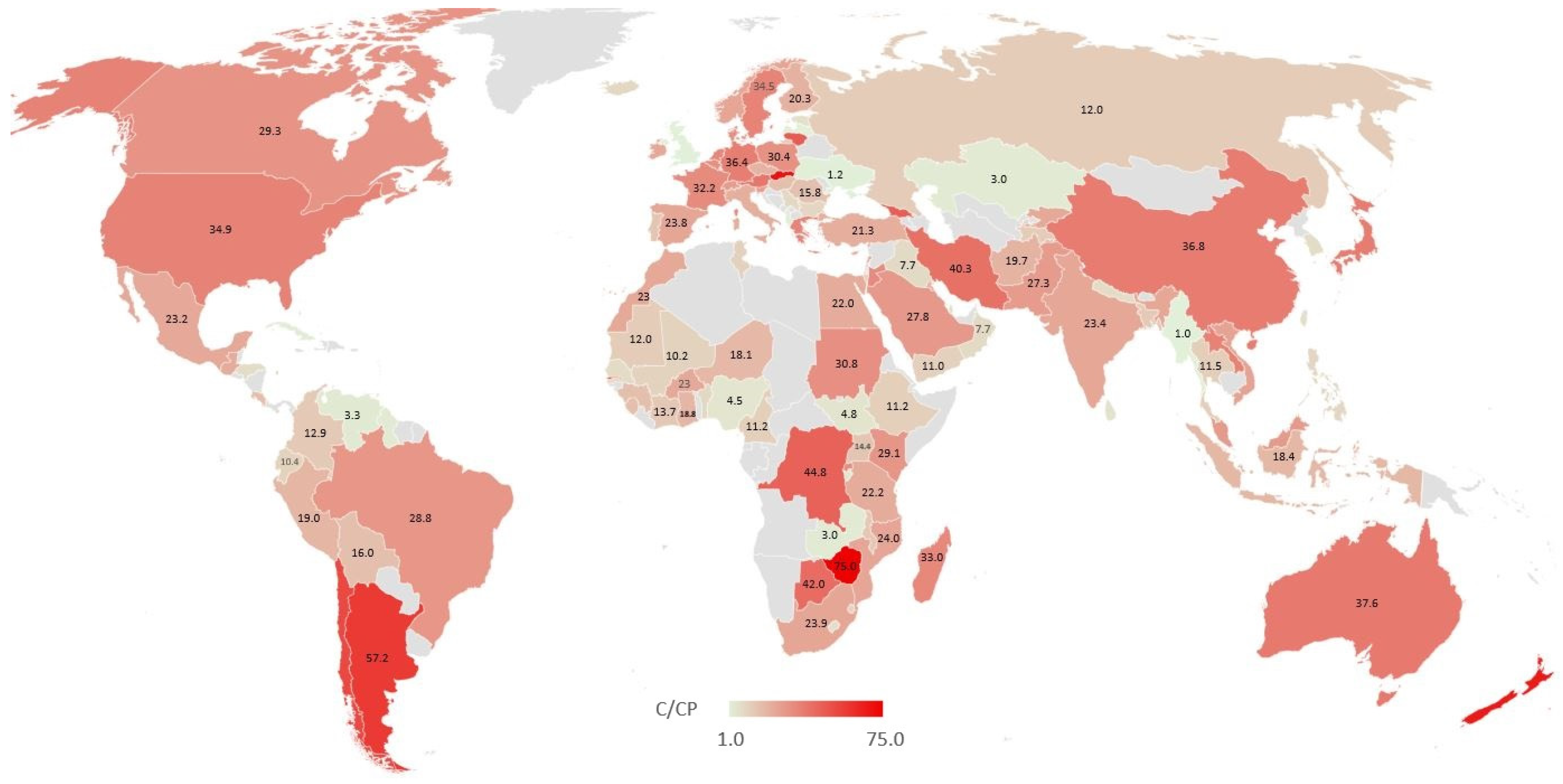

- Zimbabwe stands out with the highest C/CP ratio (75.0), implying that although the absolute number of publications is very low (1), this paper [68] that addresses various behavioral response patterns of African Farmers tends to receive substantial scholarly attention, possibly due to the high-profile of the case study and its importance for the African Continent.

- Countries like New Zealand (67.4), Argentina (57.2), China (36.81), Australia (37.63) or the United States (34.87) also exhibit high citation-per-paper ratios, reflecting a vast established academic infrastructure, strong global networks, and frequent publication in high-impact journals.

- In contrast, high-output regions like Italy (21.12), Ethiopia (11.21) or Niger (18.14) show lower C/CP values, indicating that while many papers are being produced, their individual citation impact is more modest.

- Notably, conflict-prone states such as Yemen, Syria, and Afghanistan (shown in lighter tones) have medium to upper levels of citation-per-paper ratios, suggesting that while these countries are frequently mentioned, they are often the subjects of external research rather than producers of high-impact academic work themselves, but the work they produce still gathers attention.

3.2. Is There a Bias in the Academic Research Ecosystem Going More Towards Depoliticizing Food-Related Violence by Framing It Primarily as a Humanitarian or Development Issue Rather than a Strategic Act of War?

3.3. Are “Unconventional” Food Supply Chains, Such as Black Markets, Informal Networks, and Underground Distribution Systems, Adequately Examined in the Literature, Particularly in Their Role During Armed Conflict?

3.4. Which Key Knowledge Gaps and Underexplored Themes Remain in the Academic Discourse on Food Security and Conflict, and How Can Researchers Strategically Address These to Enhance the Relevance and Impact of Their Work?

- -

- Neglect of certain regions and conflict types: A large share of the articles focuses on high-profile conflicts in the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa (Syria, Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia, etc.), as well as on global phenomena like food price spikes. Conflicts in other regions (e.g., Asia or Latin America) where food insecurity plays a significant role have received less attention in the English-language scholarly press. Similarly, slow-onset political crises causing hunger (e.g., Venezuela’s collapse) are often analyzed in economic terms rather than conflict terms. Future inquiry could be more geographically inclusive, examining, for example, the interplay of conflict and food security in Central America, South Asia, or the Caucasus. Also, incorporating non-English research (e.g., in Arabic, French, and Spanish) into future analyses would help bring in more diverse local perspectives and offer a more grassroots understanding of the studied topic.

- -

- Discourse and framing analysis: While the keyword analysis highlights the depoliticization vs. strategic framing issue, this has not been explicitly studied in many publications. In other words, few academic papers themselves turn the lens on how narratives are constructed. For example, future research could analyze UN Security Council debates, NGO appeals, and media coverage to see whether the rhetoric around conflict-induced hunger is shifting post—2018 (after UNSC 2417) or whether “hunger as a weapon” remains an uncomfortable topic that is sidestepped in favor of technical jargon. Understanding this will shape how future advocacy can more effectively frame the issue, either galvanizing political action or remaining in the realm of depoliticized development talk.

- -

- Integrated models of conflict-food interactions: The literature tends to silo different aspects of the conflict-food intersection. One stream looks at how food insecurity can lead to conflict (e.g., via riots or recruitment into armed groups when livelihoods fail), an approach that is often treated separately from the stream looking at how conflict causes food insecurity. In reality, on-site reports show that these dynamics form feedback loops. There is a need for holistic frameworks that merge these perspectives, possibly drawing on complex systems theory or conflict trap models. The concept of “food wars” should start including two-way connections between cause and effect. Yet, current quantitative models seldom incorporate both directions simultaneously due to data and methodological challenges. Future research could involve developing models (perhaps AI-based simulations or network analyses) that capture how food insecurity, governance, violence, climate shocks, and external aid interact in conflict-susceptible systems. Such models could identify tipping points where food insecurity might ignite violence or, conversely, where peace interventions could stabilize food systems.

4. Conclusions

- There is a growing consensus that deliberate starvation tactics violate international norms, yet they continue to be deployed with near-to-no consequences in conflicts ranging from Syria to Ethiopia [113].

- Impacts of conflict on food systems are not only immediate, causing hunger and displacement, but also long-term, undermining human development, governance, and regional stability.

- Durable solutions require a cross-sectoral approach that integrates humanitarian aid, development planning, security policy, and local knowledge. Communities affected by conflict have developed adaptive strategies, from smuggling networks to informal farming systems, that deserve closer scholarly attention and institutional support, not marginalization [114].

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Butz, E. Interview with Earl Butz; US Secretary of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 1974.

- Wilson, M. Food as a Weapon. Sci. People 1979, 11, 4 & 42. [Google Scholar]

- Conflict and Hunger. World Food Programme. Available online: https://www.wfp.org/conflict-and-hunger (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Messer, E.; Cohen, M.J. Breaking the Links Between Conflict and Hunger Redux. World Med. Health Policy 2015, 7, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renatus, F.V. Vegetius: Epitome of Military Science; Liverpool University Press—Translated Texts for Historians Series; Liverpool University Press: Liverpool, UK, 1996; ISBN 978-0-85323-910-9. [Google Scholar]

- Erdkamp, P. Hunger and the Sword: Warfare and Food Supply in Roman Republican Wars (264–30 B.C.); Classical Studies—Book Archive pre-2000; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1998; ISBN 978-90-5063-608-7. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, J. Agricultural Strategies and the Roman Military in Central Anatolia during the Early Imperial Period. Olba 2013, 21, 315–344. [Google Scholar]

- Álvarez, J.D.R. The Weaponization of Hunger: An Analysis of Food Security in Conflict and Post-Conflict Scenarios. J. Hum. Secur. Glob. Law 2024, 3, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, J. The Medieval Siege; Boydell Press: Martlesham, UK, 1992; ISBN 978-0-85115-312-4. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, S.P. The Food Distribution System During the Siege of Leningrad: 1941 to 1944. Master’s Thesis, San José State University, San Jose, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn, S. A History of the Early Medieval Siege, c.450–1200, by Peter Purton A History of the Late Medieval Siege, 1200–1500, by Peter Purton. Engl. Hist. Rev. 2012, 127, 1191–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothschild, E. Food Politics. Foreign Affairs, 1 January 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Paarlberg, R. Food as an Instrument of Foreign Policy. Proc. Acad. Political Sci. 1982, 34, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, W. Using Food as a Weapon. In Social Policy and Conflict Resolution; A Bachelor of General Studies (B.G.S.) in Philosophy; Bowling Green Studies in Applied Philosophy; Philosophy Documentation Center: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 1984; Volume 6, pp. 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Mendieta, E. Biopiracy and Bioterrorism: Banana Republics, NAFTA, and Taco Bell. Peace Change 2006, 31, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ACLED (Armed Conflict Location and Event Data). Available online: https://acleddata.com/ (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Conflict Watchlist 2025. ACLED. Available online: https://acleddata.com/global-analysis/conflict-watchlist (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- FSIN and Global Network Against Food Crises GRFC 2024. Available online: https://www.fsinplatform.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/GRFC2024-full.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2025).

- 3.3. Food Security and Livelihoods (FSL). Humanitarian Action. Available online: https://humanitarianaction.info/article/33-food-security-and-livelihoods-fsl (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- IRC 2024 Annual Report. 2024. Available online: https://www.rescue.org/2024annualreport (accessed on 10 June 2025).

- Alnabih, A.; Alnabeh, N.A.; Aljeesh, Y.; Aldabbour, B. Food Insecurity and Weight Loss during Wartime: A Mixed-Design Study from the Gaza Strip. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2024, 43, 222. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s41043-024-00700-6 (accessed on 14 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Helder, Z.; Espy, M.; Glickman, D.; Johanns, M.; Vorwerk, D.B. Foreign Affairs, 22 March 2024. Available online: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/ukraine/food-weaponization-makes-deadly-comeback (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Adopting Resolution 2417 (2018), Security Council Strongly Condemns Starving of Civilians, Unlawfully Denying Humanitarian Access as Warfare Tactics. Meetings Coverage and Press Releases. Available online: https://press.un.org/en/2018/sc13354.doc.htm (accessed on 24 June 2025).

- Cohen, M.J.; Messer, E. Food Wars: Conflict, Hunger, and Globalization; Oxfam: Nairobi, Kenia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fragility, Conflict and Violence. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/collections/FCV (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- World—World Food Security Outlook. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/6103 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- von Grebmer, K.; Bernstein, J.; Delgado, C.; Smith, D.; Wiemers, M.; Schiffer, T.; Hanano, A.; Towey, O.; Ní Chéilleachair, R.; Foley, C.; et al. 2021 Global Hunger Index: Hunger and Food Systems in Conflict Settings; Welthungerhilfe and Concern Worldwide: Bonn, Germany; Dublin, Ireland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, D.; Hao, M.; Li, N.; Jiang, D. Assessing the Impact of Armed Conflict on the Progress of Achieving 17 Sustainable Development Goals. iScience 2024, 27, 111331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beciu, S.; Arghiroiu, G.A.; Bobeică, M. From Origins to Trends: A Bibliometric Examination of Ethical Food Consumption. Foods 2024, 13, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N.; Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, D.; Pandey, N.; Lim, W.M. How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninkov, A.; Frank, J.R.; Maggio, L.A. Bibliometrics: Methods for Studying Academic Publishing. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2022, 11, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raan, T. Advances in Bibliometric Analysis: Research Performance Assessment and Science Mapping. Bibliometr. Use Abus. Rev. Res. Perform. 2014, 87, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Passas, I. Bibliometric Analysis: The Main Steps. Encyclopedia 2024, 4, 1014–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, O.; Kocaman, R.; Kanbach, D.K. How to Design Bibliometric Research: An Overview and a Framework Proposal. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2024, 18, 3333–3361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristia, K.; Kovács, S.; Bács, Z.; Rabbi, M.F. A Bibliometric Analysis of Sustainable Food Consumption: Historical Evolution, Dominant Topics and Trends. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, W. Food Security Review Based on Bibliometrics from 1991 to 2021. Foods 2022, 11, 3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, M.; Himpel, F. Building Resilience in Food Security: Sustainable Strategies Post-COVID-19. Sustainability 2024, 16, 995. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/16/3/995 (accessed on 3 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.; Carey, R.; Alexandra, L. Building the Resilience of Agri-Food Systems to Compounding Shocks and Stresses: A Case Study from Melbourne, Australia. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1130978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abay, K.A.; Breisinger, C.; Glauber, J.; Kurdi, S.; Laborde, D.; Siddig, K. The Russia-Ukraine War: Implications for Global and Regional Food Security and Potential Policy Responses. Glob. Food Secur.-Agric. Policy 2023, 36, 100675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saidi, M. Caught off Guard and Beaten: The Ukraine War and Food Security in the Middle East. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 983346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atinmo, T.; Mirmiran, P.; Oyewole, O.E.; Belahsen, R.; Serra-Majem, L. Breaking the Poverty/Malnutrition Cycle in Africa and the Middle East. Nutr. Rev. 2009, 67, S40–S46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. UN Goal 2: Zero Hunger. United Nations Sustainable Development 2016; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmi, A. biblioMagika®. Available online: https://bibliomagika.com/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Doocy, S.; Sirois, A.; Anderson, J.; Tileva, M.; Biermann, E.; Storey, J.D.; Burnham, G. Food Security and Humanitarian Assistance among Displaced Iraqi Populations in Jordan and Syria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011, 72, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, M.; Zeitoun, M.; El Sheikh, R. Conflict and Social Vulnerability to Climate Change: Lessons from Gaza. Clim. Dev. 2011, 3, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibnouf, F.O. Challenges and Possibilities for Achieving Household Food Security in the Western Sudan Region: The Role of Female Farmers. Food Secur. 2011, 3, 215–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olack, B.; Burke, H.; Cosmas, L.; Bamrah, S.; Dooling, K.; Feikin, D.R.; Talley, L.E.; Breiman, R.F. Nutritional Status of Under-Five Children Living in an Informal Urban Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. J. Heatlh Popul. Nutr. 2011, 29, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, O. The Politics of Starvation Deaths in West Bengal: Evidence from the Village of Amlashol. J. South Asian Dev. 2011, 6, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dancause, K.N.; Akol, H.A.; Gray, S.J. Beer Is the Cattle of Women: Sorghum Beer Commercialization and Dietary Intake of Agropastoral Families in Karamoja, Uganda. Soc. Sci. Med. 2010, 70, 1123–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leidman, E.; Tromble, E.; Yermina, A.; Johnston, R.; Isokpunwu, C.; Adeniran, A.; Bulti, A. Acute Malnutrition Among Children, Mortality, and Humanitarian Interventions in Conflict-Affected Regions—Nigeria, October 2016–March 2017. MMWR-Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2017, 66, 1332–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueck, T.; d’Errico, M.; Pietrelli, R. The Effects of Violent Conflict on Household Resilience and Food Security: Evidence from the 2014 Gaza Conflict. World Dev. 2019, 119, 203–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belsey-Priebe, M.; Lyons, D.; Buonocore, J.J. COVID-19′s Impact on American Women’s Food Insecurity Foreshadows Vulnerabilities to Climate Change. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 6867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amare, M.; Abay, K.A.; Tiberti, L.; Chamberlin, J. COVID-19 and Food Security: Panel Data Evidence from Nigeria. Food Policy 2021, 101, 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heck, S.; Campos, H.; Barker, I.; Okello, J.J.; Baral, A.; Boy, E.; Brown, L.; Birol, E. Resilient Agri-Food Systems for Nutrition amidst COVID-19: Evidence and Lessons from Food-Based Approaches to Overcome Micronutrient Deficiency and Rebuild Livelihoods after Crises. Food Secur. 2020, 12, 823–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Hassen, T.; El Bilali, H. Impacts of the Russia-Ukraine War on Global Food Security: Towards More Sustainable and Resilient Food Systems? Foods 2022, 11, 2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyfroidt, P.; de Bremond, A.; Ryan, C.M.; Archer, E.; Aspinall, R.; Chhabra, A.; Camara, G.; Corbera, E.; DeFries, R.; Diaz, S.; et al. Ten Facts about Land Systems for Sustainability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2109217118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luc, G.; Keita, M.; Houssoube, F.; Wabyona, E.; Constant, A.; Bori, A.; Sadik, K.; Marshak, A.; Osman, A.M. Community Clustering of Food Insecurity and Malnutrition Associated with Systemic Drivers in Chad. Food Nutr. Bull. 2023, 44, S69–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, K.; Verdin, A.; Brown, M.; Bakhtsiyarava, M.; Backer, D.; Billing, T. Conflict and Climate Factors and the Risk of Child Acute Malnutrition Among Children Aged 24-59 Months: A Comparative Analysis of Kenya, Nigeria, and Uganda. Spat. Demogr. 2022, 10, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Daalen, K.R.; Dada, S.; James, R.; Ashworth, H.C.; Khorsand, P.; Lim, J.; Mooney, C.; Khankan, Y.; Essar, M.Y.; Kuhn, I.; et al. Impact of Conditional and Unconditional Cash Transfers on Health Outcomes and Use of Health Services in Humanitarian Settings: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. BMJ Glob. Health 2022, 7, e007902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrihet, H.G.; Gebresilassie, Y.H.; Gebreselassie, M.A. Food Insecurity and Coping Strategies in War-Affected Urban Settings of Tigray, Ethiopia. Economies 2025, 13, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Jebreen, K.; Swaitti, T.; Jebreen, M.; Radwan, E.; Kammoun-Rebai, W.; Nawajah, I.; Shamsti, O.; Obeid, S.; Hallit, S. Dying of Starvation If Not from Bombs: Assessing Measurement Properties of the Food Insecurity Experiences Scale (FIES) in Gaza’s Civilian Population Experiencing the World’s Worst Hunger Crisis. Int. J. Equity Health 2025, 24, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Hatab, A. Africa’s Food Security under the Shadow of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Strateg. Rev. S. Afr. 2022, 44, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Alnafrah, I. Food Security in Pakistan: Investigating the Spillover Effect of Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Sustain. Futures 2024, 8, 100300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokopa, I.; Rykovska, O.; Mykhailenko, O.; Fraier, O. The Agriculture of Ukraine amidst War and Agroecology as a Driver of Post-War Reconstruction. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2024, 126, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, J.K. The Corporate Food Regime in Conflict Zones: Armed Violence and Agriculture in the Zona de Reserva Campesina-Valle Del Rio Cimitarra, Colombia. Geoforum 2024, 156, 104112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambin, E.F.; Meyfroidt, P. Global Land Use Change, Economic Globalization, and the Looming Land Scarcity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 3465–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borras, S.M.; Franco, J.C.; Gomez, S.; Kay, C.; Spoor, M. Land Grabbing in Latin America and the Caribbean. J. Peasant Stud. 2012, 39, 845–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mapfumo, P.; Adjei-Nsiah, S.; Mtambanengwe, F.; Chikowo, R.; Giller, K.E. Participatory Action Research (PAR) as an Entry Point for Supporting Climate Change Adaptation by Smallholder Farmers in Africa. Environ. Dev. 2013, 5, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpoghelie, E.O.; Chiadika, E.O.; Edo, G.I.; Al-Baitai, A.Y.; Zainulabdeen, K.; Keremah, S.C.; Ainyanbhor, I.E.; Akpoghelie, P.O.; Owheruo, J.O.; Onyibe, P.N.; et al. Malnutrition and Food Insecurity in Northern Nigeria: An Insight into the United Nations World Food Program (WFP) in Nigeria. Discov. Food 2024, 4, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-zangabila, K.; Adhikari, S.P.; Wang, Q.; Sunil, T.S.; Rozelle, S.; Zhou, H. Alarmingly High Malnutrition in Childhood and Its Associated Factors A Study among Children under 5 in Yemen. Medicine 2021, 100, e24419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lander, B.; Richards, R.V. Addressing Hunger and Starvation in Situations of Armed Conflict—Laying the Foundations for Peace. J. Int. Crim. Justice 2019, 17, 675–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranchant, J.-P.; Gelli, A.; Bliznashka, L.; Diallo, A.S.; Sacko, M.; Assima, A.; Siegel, E.H.; Aurino, E.; Masset, E. The Impact of Food Assistance on Food Insecure Populations during Conflict: Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment in Mali. World Dev. 2019, 119, 185–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.K.; Kafri, R.; Hammoudeh, W.; Mitwalli, S.; Jamaluddine, Z.; Ghattas, H.; Giacaman, R.; Leone, T. Pathways to Food Insecurity in the Context of Conflict: The Case of the Occupied Palestinian Territory. Confl. Health 2022, 16, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Waal, A. Mass Starvation: The History and Future of Famine; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; ISBN 978-1-5095-2466-2. [Google Scholar]

- Warsame, A.A.; Abdukadir Sheik-Ali, I.; Hassan, A.A.; Sarkodie, S.A. The Nexus between Climate Change, Conflicts and Food Security in Somalia: Empirical Evidence from Time-Varying Granger Causality. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2347713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassoun, A.; Al-Muhannadi, K.; Hassan, H.F.; Hamad, A.; Khwaldia, K.; Buheji, M.; Al Jawaldeh, A. From Acute Food Insecurity to Famine: How the 2023/2024 War on Gaza Has Dramatically Set Back Sustainable Development Goal 2 to End Hunger. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1402150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tezanos-Vazquez, S. Why Do Famines Still Occur in the 21st Century? A Review on the Causes of Extreme Food Insecurity. J. Econ. Surv. 2024, 39, 1433–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abebe, M.G. Impacts of Urbanization on Food Security in Ethiopia. A Review with Empirical Evidence. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 15, 100997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Fransen, S. Exploring Migration Decision-Making and Agricultural Adaptation in the Context of Climate Change: A Systematic Review. World Dev. 2024, 179, 106600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munialo, C.D.; Mellor, D.D. A Review of the Impact of Social Disruptions on Food Security and Food Choice. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyeaka, H.; Duan, K.; Miri, T.; Pang, G.; Shiu, E.; Pokhilenko, I.; Ogtem-Young, O.; Jabbour, L.; Miles, K.; Khan, A.; et al. Achieving Fairness in the Food System. Food Energy Secur. 2024, 13, e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, M.A. Climate Variability and Livelihood in Somaliland: A Review of the Impacts, Gaps, and Ways Forward. Cogent Soc. Sci. 2024, 10, 2299108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Munoz, F.; Soto-Bruna, W.; Baptiste, B.L.G.; Leon-Pulido, J. Evaluating Food Resilience Initiatives Through Urban Agriculture Models: A Critical Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Kumar, S.; Kasala, K.; Nedumaran, S.; Paithankar, P.; Kumar, A.; Jain, A.; Avinandan, V. Effects of Climate Change on Food Security and Nutrition in India: A Systematic Review. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 9, 100286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannotti, L.; Kleban, E.; Fracassi, P.; Oenema, S.; Lutter, C. Evidence for Policies and Practices to Address Global Food Insecurity. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2024, 45, 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naim, R.M.; Mutalib, M.A.; Shamsuddin, A.S.; Lani, M.N.; Ariffin, I.A.; Tang, S.G.H. Navigating the Environmental, Economic and Social Impacts of Sustainable Agriculture and Food Systems: A Review. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 652–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridge, R.; Lin, T.K. Evidence on the Impact of Community Health Workers in the Prevention, Identification, and Management of Undernutrition amongst Children under the Age of Five in Conflict-Affected or Fragile Settings: A Systematic Literature Review. Confl. Health 2024, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Ben Hassen, T. Regional Agriculture and Food Systems Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Case of the Near East and North Africa Region. Foods 2024, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, L.A.P.; Mendez, M.R.; Munoz-Rojas, J. Territorial Embeddedness of Sustainable Agri-Food Systems: A Systematic Review. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 49, 948–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Bilali, H.; Ben Hassen, T. Disrupted Harvests: How Ukraine–Russia War Influences Global Food Systems—A Systematic Review. Policy Stud. 2024, 45, 310–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.; Nguyen, M. The Impacts of Armed Conflict on Child Health: Evidence from 56 Developing Countries. J. Peace Res. 2023, 60, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooding, C.; Musa, S.; Lavin, T.; Sibeko, L.; Ndikom, C.M.; Iwuagwu, S.; Ani-Amponsah, M.; Maduforo, A.N.; Salami, B. Nutritional Challenges among African Refugee and Internally Displaced Children: A Comprehensive Scoping Review. Children 2024, 11, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldous, C. Contesting Famine: Hunger and Nutrition in Occupied Japan, 1945–1952. J. Am. East Asian Relat. 2010, 17, 230–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malarney, S.K. Dangerous Meats in Colonial Ha Noi. J. Vietnam. Stud. 2018, 13, 80–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moure, K. La Capitale de La Faim: Black Market Restaurants in Paris, 1940–1944. Fr. Hist. Stud. 2015, 38, 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnreich, H.J. Illicit Food Access Smuggling, Theft, and the Black Market. In Atrocity of Hunger: Starvation in the Warsaw, Lodz and Krakow Ghettos During World War II; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Moure, K. Food rationing and the black market in france (1940–1944). Fr. Hist. 2010, 24, 262–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Texeira, E.B. Hunger in Post-War Spain: Power, Survival Strategies, and Daily Resistance from a ⟪Micro⟫ Perspective (Malaga, 1939–1951). Hist. Y Mem. 2023, 27, 177–210. [Google Scholar]

- Roman Ruiz, G.; del Arco Blanco, M.A. Resisting with Hunger? Everyday Strategies Against the Post-War Francoist Autarchy. AYER 2022, 126, 107–130. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano, A.N. “Scarcity Becomes Famine”: Historiographical Reflection on Supply and Scarcity in the Study of the Spanish Civil War. Rev. DE Historiogr. 2024, 39, 447–472. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, Y.; Bojnec, S.; Daraz, U.; Zulpiqar, F. Exploring the Nexus between Poor Governance and Household Food Security. Econ. Change Restruct. 2024, 57, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, A. Hunger in Global War Economies: Understanding the Decline and Return of Famines. Disasters 2025, 49, e12661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, M. Time at its margins: Cattle Smuggling across the India-Bangladesh Border. Cult. Anthropol. 2020, 35, 546–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, M.; Hardesty, B.D.; Wilcox, C. The Intersection Between Illegal Fishing, Crimes at Sea, and Social Well-Being. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 589000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran-Alcrudo, D.; Falco, J.R.; Raizman, E.; Dietze, K. Transboundary Spread of Pig Diseases: The Role of International Trade and Travel. BMC Vet. Res. 2019, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.A.; Abdullah, S.M.; Khardali, I.A.; Shaikhain, G.A.; Oraiby, M.E. Evaluation of Pesticides Multiresidue Contamination of Khat Leaves from Jazan Region, Kingdome Saudi Arabia, Using Solid-Phase Extraction—Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2013, 95, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronov, K.; Ivanchenko, E.; Kachuriner, V. Customs control of foreign economic activity in the agricultural sector: Economic and legal aspects. Balt. J. Econ. Stud. 2024, 10, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN. Letter Dated 22 January 2021 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen Addressed to the President of the Security Council; UN. Panel of Experts Established pursuant to Security Council Resolution 2140, Ed.; UN: New York, NY, USA, 2014; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- World Food Programme. WFP 2025 Global Outlook; World Food Programme: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Townsend, R.; Verner, D.; Adubi, A.; Saint-Geours, J.; Leao, I.; Juergenliemk, A.; Robertson, T.; Williams, M.; Preneuf, F.; Jonasova, M.; et al. Future of Food: Building Stronger Food Systems in Fragility, Conflict, and Violence Settings; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024—Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms; FAO: Rome, Italy; IFAD: Rome, Italy; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA; WFP: Rome, Italy; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sova, C.; Zembilci, E. Dangerously Hungry: The Link Between Food Insecurity and Conflict. 2023. Available online: https://www.csis.org/analysis/dangerously-hungry-link-between-food-insecurity-and-conflict (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Jaspars, S.; Kuol, L.B.D. Famine and Food Security: New Trends and Systems or Politics as Usual? An Introduction. Disasters 2025, 49, e12669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, P. The History and Future of African Rice Food Security and Survival in a West African War Zone. Afr. Spectr. 2006, 41, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Bene, C.; d’Hotel, E.M.; Pelloquin, R.; Badaoui, O.; Garba, F.; Sankima, J.W. Resilience—And Collapse—of Local Food Systems in Conflict Affected Areas; Reflections from Burkina Faso. World Dev. 2024, 176, 106521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Description | Values |

|---|---|

| Time span | 2010−2025 |

| Documents before applying exclusion criteria | 1687 |

| Documents (articles and review papers)—after applying exclusion criteria | 1235 |

| Authors | 5300 |

| Affiliations | 3365 |

| Countries | 130 |

| Cited papers | 1099 |

| Times cited—all databases | 29,432 |

| Citations per cited paper (average) | 26.78 |

| Unique keywords | 3681 |

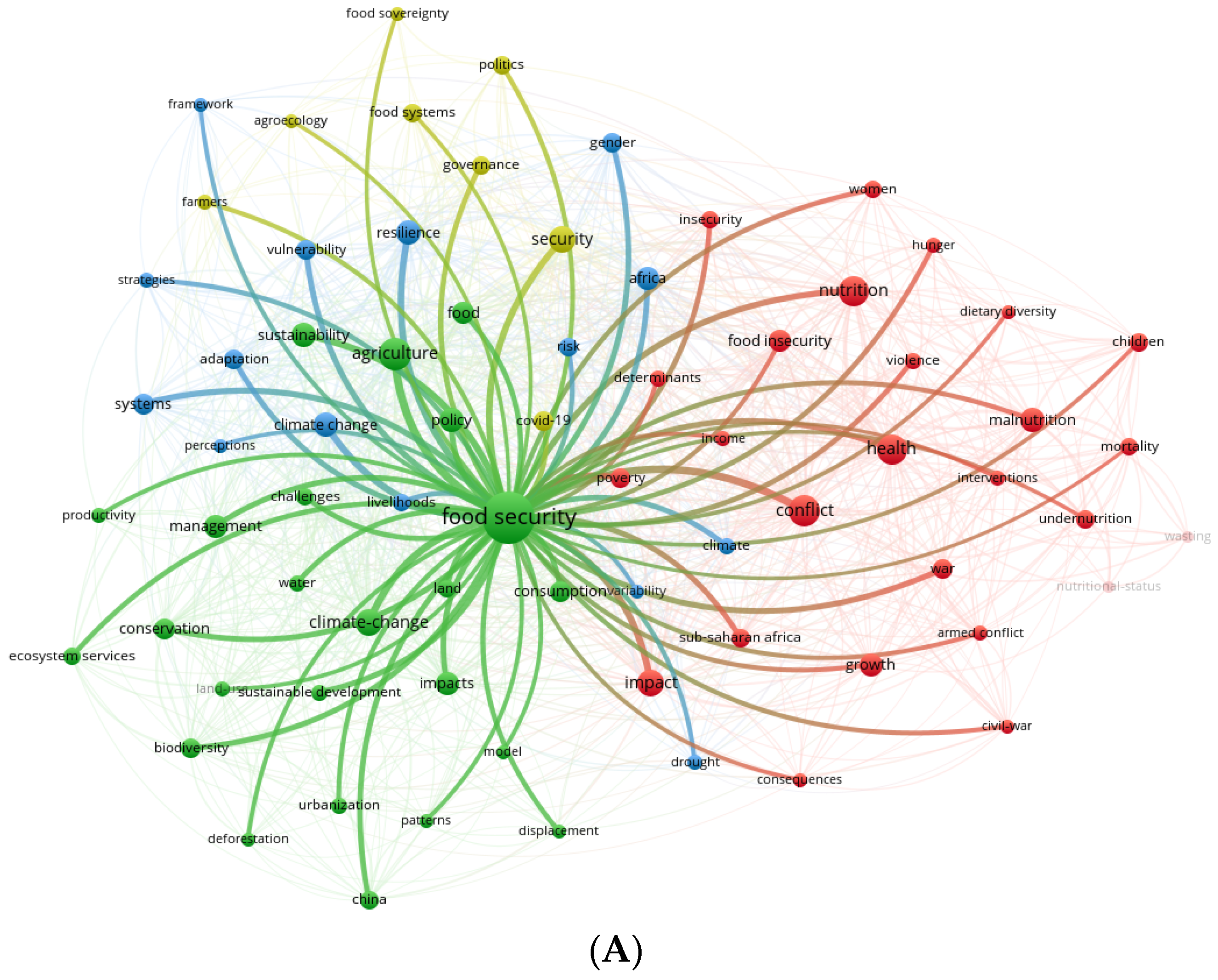

| Keywords | Mentions |

|---|---|

| FOOD SECURITY | 268 |

| CLIMATE CHANGE | 77 |

| AGRICULTURE | 59 |

| CONFLICT | 57 |

| NUTRITION | 53 |

| MALNUTRITION | 48 |

| FOOD INSECURITY | 48 |

| RESILIENCE | 44 |

| COVID-19 | 40 |

| SUSTAINABILITY | 39 |

| FOOD SYSTEMS | 36 |

| SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA | 28 |

| AFRICA | 28 |

| GENDER | 27 |

| SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT | 24 |

| WAR | 19 |

| STARVATION (WAR/CRIMES/DEATH) | 3 |

| WEAPONIZING FOOD | 1 |

| Source Title | TP | NCA | NCP | TC | C/P | C/CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SUSTAINABILITY | 56 | 238 | 52 | 1045 | 18.66 | 20.10 |

| FRONTIERS IN SUSTAINABLE FOOD SYSTEMS | 41 | 239 | 33 | 382 | 9.32 | 11.58 |

| LAND USE POLICY | 30 | 117 | 29 | 1570 | 52.33 | 54.14 |

| FOOD SECURITY | 22 | 84 | 19 | 475 | 21.59 | 25.00 |

| WORLD DEVELOPMENT | 21 | 86 | 21 | 761 | 36.24 | 36.24 |

| PLOS ONE | 19 | 136 | 13 | 226 | 11.89 | 17.38 |

| BMC PUBLIC HEALTH | 18 | 121 | 15 | 411 | 22.83 | 27.40 |

| LAND | 17 | 102 | 15 | 321 | 18.88 | 21.40 |

| GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY | 16 | 54 | 15 | 503 | 31.44 | 33.53 |

| MATERNAL AND CHILD NUTRITION | 16 | 88 | 13 | 322 | 20.13 | 24.77 |

| Source Title | TP | NCA | NCP | TC | C/P | C/CP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNAS | 5 | 71 | 5 | 2969 | 593.80 | 593.80 |

| LAND USE POLICY | 30 | 117 | 29 | 1570 | 52.33 | 54.14 |

| SUSTAINABILITY | 56 | 238 | 52 | 1045 | 18.66 | 20.10 |

| WORLD DEVELOPMENT | 21 | 86 | 21 | 761 | 36.24 | 36.24 |

| JOURNAL OF PEASANT STUDIES | 9 | 20 | 9 | 686 | 76.22 | 76.22 |

| FOODS | 14 | 49 | 13 | 618 | 44.14 | 47.54 |

| FOOD POLICY | 15 | 44 | 15 | 613 | 40.87 | 40.87 |

| REGIONAL ENV. CHANGE | 8 | 25 | 8 | 537 | 67.13 | 67.13 |

| GLOBAL ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE | 3 | 11 | 3 | 520 | 173.33 | 173.33 |

| GLOBAL FOOD SECURITY-AGR. POLICY | 16 | 54 | 15 | 503 | 31.44 | 33.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arghiroiu, G.A.; Bobeică, M.; Beciu, S.; Mann, S. From Crisis to Resilience: A Bibliometric Analysis of Food Security and Sustainability Amid Geopolitical Challenges. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188423

Arghiroiu GA, Bobeică M, Beciu S, Mann S. From Crisis to Resilience: A Bibliometric Analysis of Food Security and Sustainability Amid Geopolitical Challenges. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188423

Chicago/Turabian StyleArghiroiu, Georgiana Armenița, Maria Bobeică, Silviu Beciu, and Stefan Mann. 2025. "From Crisis to Resilience: A Bibliometric Analysis of Food Security and Sustainability Amid Geopolitical Challenges" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188423

APA StyleArghiroiu, G. A., Bobeică, M., Beciu, S., & Mann, S. (2025). From Crisis to Resilience: A Bibliometric Analysis of Food Security and Sustainability Amid Geopolitical Challenges. Sustainability, 17(18), 8423. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188423