1. Introduction

The framework of cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) has become increasingly popular for analyzing and promoting sustainable innovation in workplace and educational settings. During the Change Laboratory (CL), the participants in an organization jointly examine their work activity with the help of a researcher; by critically inspecting the complexity and challenges of their organization, they identify the most aggravated contradictions and begin to design a new model or concept that resolves the contradictions [

1]. In this journal, for example, Scahill and Bligh [

2] showcased how the CL facilitated sustainable institutional change in higher education by fostering collaborative reflection and innovation among faculty, highlighting systemic tensions that were addressed through collective problem-solving. Similarly, Kaup and Dau [

3] applied this method in a primary school setting, demonstrating how it enhanced teacher collaboration and supported inclusive education.

In CHAT, the concept of contradiction—understood as historically accumulated and structural tensions that arise within and between activity systems [

4]—plays a central role. Once contradictions are identified, they can be dealt with, and in so doing, they become the driving force for the change and development of an organization. In this journal, Ho and Qi [

5] identified contradictions in middle school mathematics teaching that impeded curriculum implementation, highlighting tensions between traditional instructional methods and innovative pedagogies. Meanwhile, Du [

6] explored the contradictions faced by teachers in professional development for English for academic purposes, revealing challenges in aligning institutional goals with teachers’ practical needs and agency.

Due to their systemic and historically accumulated nature, however, contradictions often remain implicit in everyday interactions and work practices, rendering direct observation challenging. To address this, Engeström and Sannino [

7] developed an analytical framework focusing on discursive manifestations—observable patterns in language such as dilemmas, conflicts, and double binds—that signal the presence of underlying contradictions and provide a means to systematically identify and address them in organizational settings. Though this framework has proven effective in analyzing transcripts from CL sessions [

7,

8,

9,

10] and individual interviews [

11,

12], there remains a notable gap in applying it to identify discursive manifestations of contradictions prior to interventions. Early detection of these contradictions is crucial, as it can inform the design and facilitation of interventions, ensuring they are responsive to historically rooted tensions, thereby enhancing the potential for sustainable organizational transformation.

Furthermore, while Dinh and Sannino [

13] recently proposed a diagnostic tool for inspecting needs and challenges in preparation for a prospective CL in a school and Cassandre et al. [

14] suggested a situation mapping tool in preparation for a CL in a hospital, there is a need for an instrument to help identify contradictions before the CL takes place. This article fills this gap by proposing a semi-structured interview method to analyze discursive manifestations of contradictions prior to a CL intervention. In a kindergarten located in Italy, teachers, special teachers, janitors, and cooks were briefly interviewed on the challenges affecting their organization. Interviews were transcribed and examined by applying the framework developed by Engeström and Sannino [

7]. Theoretically, this paper positions discursive manifestations as a diagnostic lens for the early identification of systemic tensions that signal readiness for expansive learning. The research questions are as follows:

What types of discursive manifestations of contradictions can be identified in interviews with kindergarten staff prior to a Change Laboratory intervention?

What types of systemic contradictions can be hypothesized from these manifestations?

How can the analysis of these discursive manifestations support the preparation and facilitation of a Change Laboratory intervention in a kindergarten setting?

To answer these questions, this paper begins by reviewing the main principles of CHAT and literature on discursive manifestations of contradictions. The methods section displays the context of the research, the structure of the interviews that sought to elicit discursive manifestations, and how they were analyzed. The results show dilemmas, conflicts, and critical conflicts that the participants experienced prior to the CL and the main themes that emerged from the thematic analysis, which are then represented through the triangle of human activity. Finally, the article considers how such interviews can inform the preparation and facilitation of a CL.

2. Theoretical Framework: Cultural Historical Activity Theory and Discursive Manifestations of Contradictions

Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) is a multidisciplinary framework for understanding how people think and act together within their cultural and historical contexts [

4]. It offers a powerful lens for understanding educational processes because it conceptualizes learning as a socially mediated, culturally and historically situated activity rather than an isolated cognitive process [

15]. In kindergartens, this perspective positions pupils as active, historical agents whose voices and identities develop through engagement in meaningful, real-world activities [

16]. Within this journal, only Lecusay et al. [

17] applied this framework to early education to include “care” as a concept essential for learning, thus demonstrating how joint imaginary play can be a basis for sustainable development.

In the third generation of studies, CHAT is characterized by five principles. First, the primary unit of analysis is the historically evolving activity system. An activity system is made up of interconnected elements: the subject; the artefacts used; the community context; the rules that guide actions; and the division of labor among participants. In the activity system, the object plays a pivotal role, as it gives meaning, purpose, and continuity, and it motivates and directs the collective actions of individuals. In a kindergarten, understanding the activity system enables educators to analyze how the subject (the teaching staff), tools (pedagogical methods and space), community (colleagues and parents), rules, and division of labor (teachers care for the children, and janitors maintain the physical space) interact to result in educational practices. The activity system is generally depicted through the triangular model of activity [

15], which illustrates the unit of analysis and its related components. Since such representation connects individual actions with the collective activity system and visualizes multiple mediators, such as the rules, the division of labor, and the instruments [

18], it constitutes a valuable instrument to assist practitioners in grasping what is happening on the shop floor [

7].

The second principle concerns multivoicedness [

4]: activity systems are characterized by several voices, traditions, interests, and perspectives. While such heterogeneity can create tensions, it also represents a source of innovation and should therefore be taken into account. In a kindergarten setting, this principle highlights the importance of incorporating the diverse perspectives of teachers, special educators, janitors, and parents, whose different experiences and interests contribute to their complexity and potential for innovation. The third principle concerns historicity: activity systems evolve over time, and understanding their history is key to explaining the shape that current practices have taken, as well as the potential for change. Appreciating the historicity of a kindergarten’s activity system helps to contextualize existing tensions as rooted in previous pedagogical traditions and institutional arrangements, which influence staff readiness and resistance to change. The fourth principle focuses on dialectics: it recognizes contradictions—historically accumulated structural tensions within and between activity systems—as a driving force for change and innovation. This principle underscores that identifying and discussing contradictions among mediators of human activity can potentially push the kindergarten staff toward organizational change and pedagogical transformation.

The last principle concentrates on expansive learning, a form of learning that occurs when groups involved in a collective activity transform that activity by reconceptualizing its object and motive, thereby opening a radically broader horizon of possibilities [

19]. The object becomes broader, more complex, or more future-oriented, reflecting a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities at hand. In so doing, it acts as a catalyst for systemic transformation, requiring new ways of working, new relationships, and often new identities for participants. Expansive learning is frequently promoted through formative interventions, such as the CL [

7]. During such an intervention in an early childhood setting, for example, Lipponen et al. [

20] surfaced moral–ethical tensions and inclusion challenges, underscoring its suitability for organizational change. Moreover, in a systematic review, Hopwood [

21] examined 55 studies employing CLs in school contexts and found that they were effectively utilized to foster pedagogical innovation, enhance initial teacher education, and promote collaboration across institutional boundaries.

An essential part of the expansive learning process is to examine the contradictions pervading the activity system. Based on the principle of dialectics [

19], contradictions are not just simple problems or disagreements; they do not merely represent a surface-level conflict but are structural features that shape motivations, actions, and possible developments within the activity. Engeström [

15] identifies four types of contradictions within and between activity systems. Recognizing them helps organizations and communities understand where change is needed and how to manage it constructively. At the most fundamental level, primary contradictions exist within a single component of the activity system. In a kindergarten, for instance, teachers may experience tensions between their role as caregivers and administrative expectations to focus on documentation and reporting. Furthermore, one of the most significant and recurring examples of a primary contradiction, as identified by Engeström and rooted in Marxist theory, is the tension between use value and exchange value. This contradiction is inherent in every object of the activity or tool that mediates activity. On the one hand, an object or an instrument has a use value, serving a practical function or fulfilling a need for the subject; on the other hand, it also possesses an exchange value, representing its worth in a broader economic or social context. In early education, the pupil as the object of the activity embodies an inherent contradiction between the need to keep them safe and protected and the equally vital need to allow them to learn through free, sometimes risky, experimentation and exploration.

Secondary contradictions arise between two components of the activity system, for instance between instruments and object or between community and rules. The available play equipment (tools) may not support the children’s needs for physical activity (object), causing frustration among educators who must balance the limitations of equipment with the goal of fostering active play. Tertiary contradictions arise when there is a conflict between the object or motive of the prevailing, established form of a central activity and the object or motive introduced by a culturally more advanced or innovative version of that same activity. The introduction of the open classroom model, for example, may cause resistance among educators accustomed to traditional, structured classrooms, leading to hesitation in adopting new practices. Finally, quaternary contradictions occur between the central activity system and neighboring or interacting activity systems, highlighting the challenges that arise at the boundaries of different social practices. Familial expectations for strict supervision may, for instance, differ from the kindergarten’s philosophy of fostering autonomy, leading to tensions between home and school approaches.

Contradictions are deeply embedded tensions that develop over time through evolving social practices and norms. Since they develop historically and have a systemic nature, they cannot be observed empirically and require careful qualitative reconstruction to uncover [

7]. One way is to collectively analyze everyday disturbances (i.e., deviations from the anticipated progression of work processes [

17]), as practiced during the CL sessions [

1]. Another possible approach is to look for patterns of talk and discursive action. Only qualitative research, with its interpretive and context-sensitive approach [

22], focuses on understanding how individuals make sense of their surroundings—what they do, how they do it, and what they experience—in ways that are personally meaningful [

23]. In so doing, it can uncover contradictions by revealing the meanings, experiences, and conflicts embedded in participants’ interactions and narratives. Engeström and Sannino [

7] developed a framework for finding and examining four types of discursive manifestations of contradictions, spanning from the least to the most aggravated [

24]: dilemmas, conflicts, critical conflicts, and double binds. For each type of discursive manifestation, Engeström and Sannino [

7] provided definitions and rudimentary cues—signs in people’s speech or writing, such as words, phrases, or expressions of uncertainty or disagreement.

A dilemma arises when conflicting views are expressed, either between individuals or within a person’s own thoughts. It often appears through phrases like “on the one hand… on the other hand” or “yes, but”. Rather than being resolved, dilemmas tend to persist in conversation through denial or rephrasing. Conflicts involve resistance, disagreement, or criticism and arise when individuals or groups feel harmed by others due to differing interests or incompatible behavior. They are often expressed with phrases like “no,” “I disagree,” or “this is not true”. Conflicts are usually resolved through compromise or by yielding to authority or the majority. The concept of critical conflict was first deployed by Sannino [

25] when examining teachers’ resistance and agency. In the Engeström and Sannino framework, they occur when individuals experience inner doubts and conflicting motives that they cannot resolve alone. In social settings, these often involve strongly morally or emotionally imbued narratives and are often characterized by strong metaphors. Resolving critical conflicts involves individuals creating new personal meanings and renegotiating the original situation. Lastly, double binds occur when individuals repeatedly face equally difficult and unacceptable choices with no clear escape, often escalating into crises. In conversation, they appear as rhetorical questions expressing frustration and a sense of being stuck, like “What can we do?” Resolving double binds usually requires moving from individual to collective action, reflected in urgent phrases like “we must”.

After devising this analytical framework, Engeström and Sannino [

7] proceeded to apply it in a CL conducted with home care managers in the municipality of Helsinki. The analysis follows three steps: identification of rudimentary linguistic cues; classification of discursive manifestations; and quantification and thematic analysis. The authors, however, emphasized that this process is not mechanical, that a “but” does not always mean a dilemma, and a rhetorical question does not necessarily indicate a double bind. Instead, the cues help guide the analysis, which is ultimately qualitative and interpretive [

22]. Lastly, Engeström and Sannino [

7] reconstructed the contradictions pervading the activity system with the help of the triangular model of activity [

15]. Since their seminal investigation of discursive manifestations of contradictions, other scholars have used this framework: in a CL on language learning in a university [

10]; in formative interventions to address racial disparities in a middle school [

9]; and in a primary school to identify challenges related to inclusion [

8].

While the above-mentioned studies apply the framework to the transcripts of the sessions, subsequent studies examined diverse data sources beyond CL interventions. Ivaldi and Scaratti [

26], for example, used the framework to conduct a qualitative analysis of the participants’ narrative accounts during a formative intervention in an addiction prevention unit. Other authors used the framework to examine group work: Ros and Grosen [

27] studied interprofessional teams working with people with psychiatric illnesses, while Dionne and Bourdon [

28] examined a group of professionals working with long-term unemployed individuals. Other scholars applied the framework to interviews, such as Marwan and Sweeney [

29], who conducted semi-structured interviews with English teachers in a secondary school, or Virtaluoto et al. [

24], who used unstructured interviews with technical communication professionals, while Paju et al. [

12] analyzed questionnaires completed by 167 primary education teachers, focusing on special education.

Moreover, scholars further advanced the framework through triangulating data sources: Castello et al. [

30] combined data from sessions, diaries, and interviews to investigate contradictions PhD students faced when learning to write a research article. On the topic of school readiness, Kay [

31] integrated individual interviews with group interviews with primary school teachers, and Vijayaraghavan [

32] triangulated instructors’ interviews with a students’ questionnaire to investigate the blended learning engagement when using Moodle. Recent developments of the framework include studies on the hybridization of adolescents’ worlds through semi-structured interviews [

11], thus considering multiple and interconnected activity systems, and statistical analyses of mailing lists in open-source communities [

33]. In summary, Engeström and Sannino’s framework for analyzing discursive manifestations of contradictions has been widely extended beyond Change Laboratory sessions to various other settings, including group work, semi-structured interviews, and formative interventions. Its flexibility and robustness allow researchers to uncover systemic tensions and contradictions in diverse educational contexts, facilitating a deeper understanding of organizational challenges and enabling targeted interventions for sustainable change.

3. Materials and Methods

This research was conducted in a public kindergarten located in a working-class neighborhood characterized by a high proportion of children with an immigrant background and a significant number with learning disabilities. The kindergarten, which accommodates approximately 90 children aged from two and a half to six years old across four sections, had recently reopened in September 2024 following two years of extensive renovations aimed at modernizing both its physical infrastructure and pedagogical orientation. The goal was to implement the open classroom concept, a pedagogical approach, and an organizational model for educational spaces that diverges from traditional, rigid classroom settings. In kindergarten settings, the open classroom model emphasizes child-initiated activity, free play, and flexible spatial organization [

34,

35]. Rooted in democratic and constructivist educational traditions, it offers children the autonomy to choose what, how, where, and with whom to learn and play. Teachers act as facilitators of learning rather than directors, providing a rich environment of materials, experiences, and opportunities for social interaction. Upon reopening in September 2024, however, teachers encountered significant difficulties in adapting to the new spatial layout, leading to a return to the traditional self-contained classroom structure, driven largely by inadequate shared planning, coordination challenges among educators, and a shortage of play equipment, furniture, and child-appropriate materials necessary to support an open classroom model.

At the same time, the management and the kindergarten staff became aware that they needed external help. The CL intervention was negotiated in late 2024 and started in spring 2025, with the aim of implementing the open classroom model by engaging the teaching staff in a participatory approach. Further, the objective was not only to transform practices within the selected kindergarten, but also to develop a concept that could potentially be applied across other early childhood institutions in the school district. The intervention enjoyed strong support from the school leadership, yet teachers expressed varying degrees of commitment: while many were enthusiastic and positively inclined toward open classroom philosophy, others were more ambivalent, torn between interest in innovation and attachment to established routines.

In line with the CL methodology, participant observation in the kindergarten started before the intervention in February 2025 to better understand the cultural and organizational dynamics and to gather mirror data (interviews, documents, and videos) to be used during the sessions. In parallel, semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect discursive manifestations of contradictions, such as patterns of talk and action through which practitioners articulate and make sense of tensions in their activity systems [

7]. By asking staff to reflect on challenges and problematic situations, researchers created conditions for those manifestations to surface. We chose semi-structured interviews [

36], as they are short and easy to administer and since they have already been used to surface contradictions by Marwan and Sweeney [

29], as well as Engeström et al. [

11]. The interview protocol allowed flexibility: in two cases, teachers wished to prolong the conversion, causing the interview to become unstructured.

The main topics of the interviews were time and space as central mediating conditions in the kindergarten. Children’s routines around time—such as lunch and nap periods—and the spatial organization of classrooms reflect the material and social structures that shape both pedagogical activities and staff collaboration. Disruptions or difficulties in these areas serve as concrete manifestations of contradictions inherent in transitioning from a traditional, self-contained classroom model to an open classroom model, where routines and the use of spaces change radically. The first question established a baseline for the CL, asking interviewees to rate from 1 to 10 their happiness with the current use of spaces and to explain their rating. The second question was about the use of space (2. What are the challenges concerning the current use of space?), and the third was on time. (3. What are the moments of the day you find difficult to manage?) The last two questions enquired about the object of the activity, understanding of which is crucial in CHAT [

4,

15]. Since the implementation of the open classrooms concept calls for a radical transformation of the object (the child becomes autonomous and able to make choices [

34,

35]), these questions sought to understand how teachers saw themselves in relation to the new role this transformation called for, from directors to facilitators of learning, and if such a change triggered contradictory feelings. These questions were: 4. What is your role as a teacher working with children at this school now? 5. How do you see your role as a teacher at this school at the end of the CL process?

Participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained from all staff prior to data collection. Ethical considerations included ensuring confidentiality, the option to withdraw at any time, and sensitive handling of data to respect participants’ privacy and promote an atmosphere conducive to honest and constructive input. All school personnel (N = 19) signed the consent form and participated in the interview: eight teachers, six special teachers, three janitors, and two cooks. Each interview could last from five minutes (when answers were telegraphic) to 30 min, when the interview became unstructured. Typing interview responses directly, with the help of the dictation function when possible, was chosen to minimize participant discomfort and encourage openness, especially given evidence that recording devices can inhibit authentic sharing [

37]. Although this method may limit some paralinguistic data, it allowed for richer verbal content to be captured in real-time, balancing data quality with ethical and relational considerations. The dataset of around 9,200 words underwent analysis to find discursive manifestations of contradictions as shown by Engeström and Sannino [

7]. Rudimentary cues, however, were not always of help; for example, ‘

we must’ appeared often in critical conflicts instead of double binds, and ‘

yes, but’ seemed to correlate more with conflicts than with dilemmas. Hence, in line with similar investigations, such as Cenci et al. [

8], Paju et al. [

12], and Virtaluoto et al. [

24], we decided not to quantify them. As initial orientation, instead, we decided to utilize AI to elicit concrete ideas from the body text. To support rigorous analysis, AI was employed as an initial tool to operationalize and illustrate potential discursive manifestations based on established theoretical frameworks. We uploaded on Perplexity both the article of Engeström and Sannino [

7] and the transcript, and then we asked AI to operationalize the discursive manifestations in the context of the kindergarten and, subsequently, to find examples in the transcript (if present) of what dilemmas, conflicts, critical conflicts, and double binds could look like. After seeing operationalization and possible examples, it was easier for us to proceed with the systematic search in the dataset. The AI-generated outputs were only examples, which were critically reviewed and validated. The following systematic search was carried out exclusively through recursive qualitative coding to ensure accuracy and contextual relevance. This combination enhanced both efficiency and interpretative depth without replacing human judgement.

The analysis followed the three steps indicated by Engeström and Sannino [

7]: (a) identification, (b) classification, and (c) counting and thematic analysis. Consistent with the epistemological foundations of qualitative inquiry, which is inherently interpretive [

22], we engaged in a reflexive and collaborative process of data interpretation to ensure trustworthiness and rigor [

23]. We critically reflected on our own positionalities and potential biases to minimize subjective influence and maintain fidelity to participants’ narratives. Instead of formal intercoder reliability statistics, we employed iterative readings, open discussions, and consensus-building sessions among researchers to negotiate and align interpretations, thereby enhancing coding consistency and credibility. Furthermore, thematic development was carried out inductively through a bottom-up approach involving multiple rounds of collaborative coding and detailed examination of critical conflicts. This recursive and intersubjective process allowed for nuanced identification and refinement of emergent themes that accurately represented the diverse voices and tensions within the activity system.

After identifying all the discursive manifestations in the dataset, we copied them into an Excel file to facilitate identification, classification, counting, and thematic analysis. We then conducted a thematic bottom-up analysis [

23]. Through a process of readings, discussions, and double checks, we identified the most recurring emerging themes that best described the dataset and once again quantified them to give an indication of the weight of each theme. Lastly, in line with the work of Sannino and Engeström [

7] and subsequent research on Change Laboratories [

9,

10], we represented the systemic contradictions with the help of the triangle of human activity [

15]. In relation to counting occurrences, in CHAT, the use of numbers should not be viewed as a positivist inclination to categorize reality (see Yanchar [

38]). While CHAT research does not prioritize numbers, as it is primarily qualitative [

39], these are used to indicate the strength of a phenomenon and to show the rigor of the analysis. For these reasons, in the thematic analyses, we pragmatically chose a threshold of three occurrences to highlight the most salient themes and to reflect a meaningful degree of consensus among the interviewees. While we did not find other research within CHAT using thresholds, this allowed us to focus on the prominent patterns within the data while respecting the qualitative, context-sensitive nature of the analysis [

22]. By taking this approach, we aimed to balance rigor with the nuanced understanding of participants’ diverse voices and experiences, ensuring that the themes presented are both significant and representative of shared concerns within the activity system.

5. Discussion

The first research question was:

What types of discursive manifestations of contradictions can be identified in interviews with kindergarten staff prior to a Change Laboratory intervention? The themes emerging from the interviews illustrate the multifaceted discursive manifestations of contradictions embedded within the kindergarten taken as an activity system.

Table 2 reveals distinct patterns across staff roles, highlighting varied experiences and concerns across different staff roles. Teachers reported the most manifestations, including dilemmas about adopting the open classroom pedagogy versus clinging to traditional roles, numerous conflicts over practical issues like space and routines, and critical conflicts reflecting deep struggles with professional identity, pedagogical disagreements, and challenges in collaboration. Their experiences underscore the significant cultural and organizational adjustments demanded by the pedagogical transformation. Special teachers mainly expressed conflicts focused on structural challenges, such as inadequate spaces for small groups and needs related to inclusion. They reported fewer dilemmas and no critical conflicts, suggesting clearer role boundaries but significant concern about resources and support for children with special needs. Janitors and cooks reported only a few conflicts and minimal dilemmas, mainly related to operational issues such as managing lunch routines and ensuring safety. Their limited discourse on contradictions reflects their supportive, non-pedagogical roles.

Moreover, the absence of double binds, which represent the most severe form of discursive contradictions [

24] marked by feelings of entrapment and inescapable dilemmas, may indicate that systemic tensions in the kindergarten have not yet escalated to crisis levels. Additionally, the semi-structured interviews may not have explicitly elicited the intense expressions typical of double binds, which often emerge more naturally in prolonged or dialogical settings, such as the CL [

7]. The anticipated CL intervention and leadership support might also mitigate feelings of helplessness, fostering a collective sense of agency that counters the escalation into double binds. Lastly, cultural factors may influence how openly such profound frustrations are articulated.

Research Question 2 was:

What types of systemic contradictions can be hypothesized from these manifestations within the kindergarten seen as an activity system? Concerning dilemmas, the theme related to whether to embrace the new pedagogy of the open classroom (or stay in the comfort zone of the self-contained classrooms model) may in the future be defined as a tertiary contradiction, namely between new and old activities [

15]. Teachers who displayed such dilemmas may resist implementing the new pedagogical organization [

25]. The other dilemmas regarding potential conflicts of rules or division of labor can be considered as part of the contradictions emerging in the analysis of conflicts, discussed in the following paragraph.

Furthermore, the thematic analysis of conflicts (

Table 3) shows more general themes, such as the new building being not functional and a lack of space/rooms, while others are more specific, such as chaotic lunchtimes and an unconfigured entrance hall. Overall, since the school has been renovated, there is deep dissatisfaction with routines connected to lunch, post-lunch periods, and the furnishing of spaces, especially the entrance hall. On the one hand, before and after lunch, children are confined in the corner area of each section: before lunch, when cooks set their tables, and after lunch, when janitors clean the rooms. On the other hand, lunch is rushed in all sections, especially in section C, where cots must be prepared for nap time. In CHAT terms, the instruments (sections with arrangements for lunch and nap, including cots) and the division of labor between teachers, special teachers, janitors, and cooks create tensions in the children’s routines (the result of the activity). This could be interpreted as a secondary contradiction (namely between elements of the activity system [

15]) between instruments and the object.

Critical conflicts, instead, are the most aggravated type of discursive manifestation of contradictions [

24] in the dataset. These largely indicate conflicts between teachers over pedagogies. Conflicts over pedagogies stem from different visions of the child, suggesting a primary contradiction in the object (i.e., within single elements of the activity system [

15]). This contradiction can be summarized as tension between the child as an “empty box” to be taught and the child as an autonomous being capable of independent learning. Such conflicting visions of the object imply a different vision of the teacher’s role: a director or a guide, which causes a secondary contradiction (namely between elements of the activity system [

15]) between the rules and the object. Another notable conflict comes from the teachers experiencing a breakdown in their sense of purpose, which, in CHAT terms, is termed

loss of the object [

40]. We consider this another facet of the above-mentioned secondary contradiction between the rules to carry out the activity and the object.

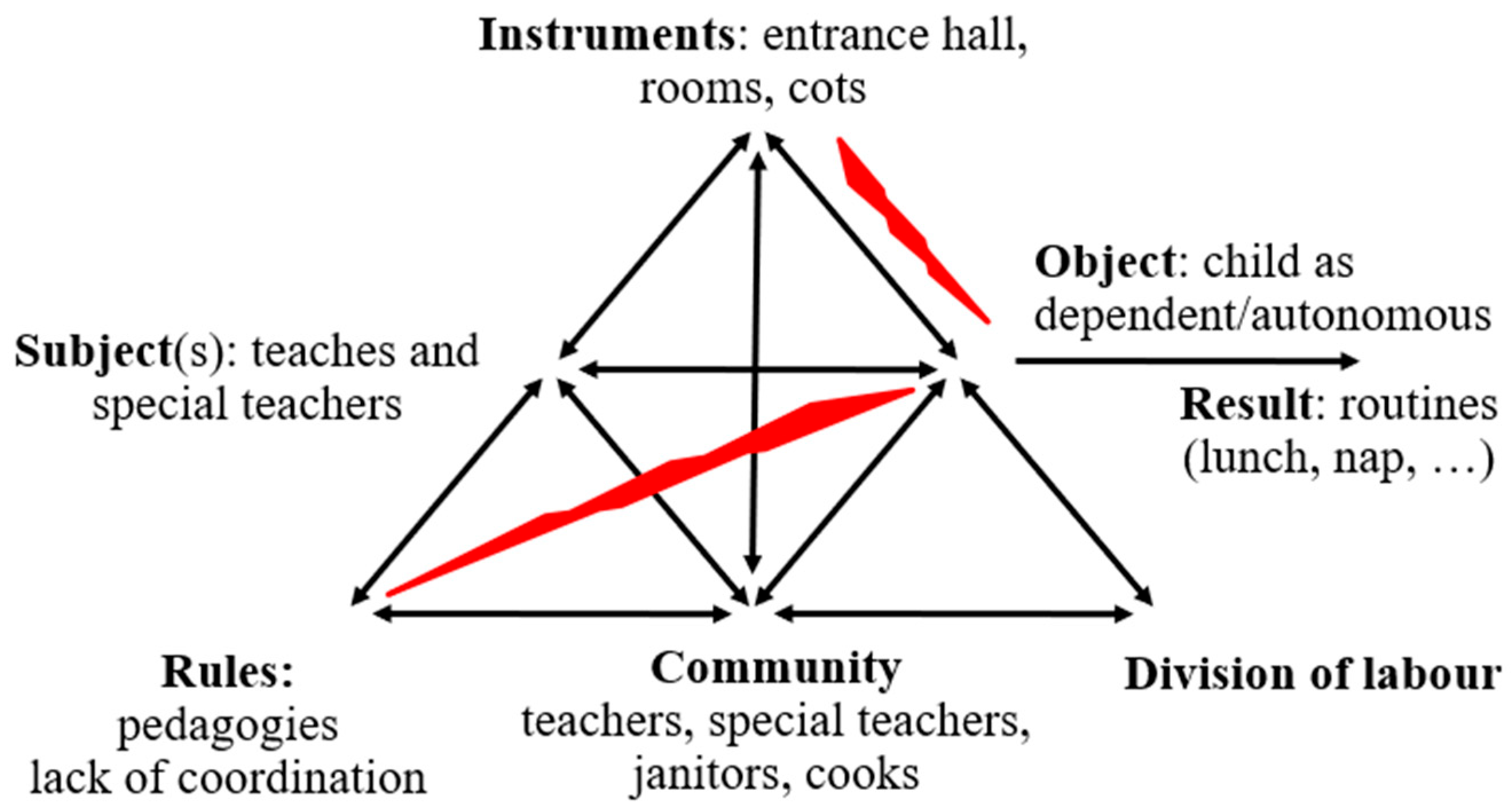

Figure 1 depicts the kindergarten’s activity system using the triangular model of human activity [

15], highlighting two key secondary contradictions. The first contradiction exists between instruments (e.g., classroom spaces, furniture, materials) and the object of the activity (facilitating autonomous child learning), reflecting tensions in how physical resources support pedagogical goals. The second contradiction lies between rules (norms and expectations governing teacher roles and practices) and the object, revealing conflicting visions of the child and teaching approaches. Together, these contradictions illustrate systemic tensions driving the need for transformative change in the kindergarten’s organization and pedagogy.

Research Question 3 was: How can the analysis of these discursive manifestations support the preparation and facilitation of a CL intervention in a kindergarten setting?

The analysis above shows that there is agreement between teachers and special teachers regarding the urgent challenges to be tackled. In other words, there is the shared feeling that something must be done about existing lunch routines and use of space. This need to manage or overcome contradictions [

15] represents a good starting point for a CL, since this intervention is normally best conducted when an organization is facing a major change [

1,

19].

Figure 1 is a powerful visualization [

16] of the kindergarten as a collective activity system and could be deployed during the CL sessions to promote deeper examination and transformation of work practices [

40]. By discussing the nature of the child and their corresponding role and pedagogies, the CL sessions could provide a place where teachers can reappropriate the object, namely to re-establish their connection with the child as the central focus and motive of their activity. This is consistent with Lipponen et al. [

20], who recently suggested that the CL in kindergarten settings can be an ideal place to discuss moral and ethical tensions.

Furthermore, given the conflicts between colleagues, the intervention will have to devise new ways for teachers to work together. According to Virkkunen and Newnham [

1], one way to do this is to discuss the concepts of

coordination, cooperation, and communication. Since teamwork unfolds like actors following a script [

41], coordination is when team members follow a shared “script”—a set of explicit rules, plans, or tacit traditions—without questioning or discussing them. Each participant focuses on performing their assigned role as it is now with the self-contained classroom model. When problems arise, cooperation occurs, and team members step out of their roles to solve a shared issue, stretching the script but not rewriting it. Communication, instead, leads to a breakthrough—here, the team openly questions and reshapes the script itself, transforming how they work together. Discussing these concepts during the CL sessions will raise participants’ awareness that in the present self-contained classroom model, they are in the situation of coordination, but if they want to implement the open classrooms model, they need to design new scripts for effective teamwork.

Analysis also suggests some teachers are reluctant to embrace the open classroom model, and their concerns must be addressed in the change process. It will be important, therefore, to allow their concerns to emerge and to discuss possible pros and cons of the open classroom model during the CL sessions. The participants, however, will have to be reassured that the goal of a CL is not to implement the ideologically perfect open classroom model but rather to devise a new model that addresses the challenges facing the school and best fits its concrete reality [

42]. From this point of view, the open classroom model will only be used to the extent that it helps resolve the historically aggravated contradictions pervading the kindergarten. This also implies a negotiated open mandate with the director of the school district, as recommended in CL interventions [

1], granting the teaching staff autonomy to design a pedagogical model that best fits the kindergarten’s specific context, rather than rigidly implementing the open classroom model as if it were an ideological abstraction [

42].

6. Conclusions

This study developed and applied an interview-based approach grounded in CHAT. It aimed to identify and analyze discursive manifestations of contradictions within a kindergarten prior to a CL intervention. The framework for inspecting discursive manifestations of contradictions, initially developed by Engeström and Sannino [

7], has since evolved and been applied in various ways and contexts. Analyses have varied. Some focused on discursive manifestations without examining rudimentary cues. Others hypothesized systemic contradictions, illustrating these with the triangular activity model. Additionally, some studies employed robust triangulation, combining qualitative and quantitative thematic analyses. Others presented only illustrative quotes without deeper examination. In our view, it is important that the framework is applied in a rigorous and transparent way. This study contributes to the expanding body of research applying CHAT to early childhood education by demonstrating how discursive manifestations of contradictions can be effectively surfaced prior to formal intervention. It offers an interview model designed to elicit discursive manifestations of contradictions within a kindergarten. Firstly, it offers an interview model to elicit discursive manifestations of contradictions within a kindergarten. Secondly, it provides a step-by-step, rigorous framework for identifying and mapping contradictions in the activity system, beginning with systematic interview data inspection and culminating in a graphical representation.

This study offers valuable practical implications for educational institutions seeking to implement organizational change through participatory methods, such as the CL. By hypothesizing main systemic contradictions early through semi-structured interviews, educational leaders and facilitators can better tailor interventions to address underlying tensions related to space, routines, pedagogical philosophies, and staff collaboration. The findings highlight the importance of involving diverse staff voices—not only teachers but also special teachers, janitors, and cooks—to gain a comprehensive understanding of the organizational challenges and foster shared ownership of the change process. Practically, this approach equips CL facilitators with concrete themes and guiding points to structure productive sessions that are grounded in the lived realities of the institution. By supporting the preparation and facilitation of the CL in this way, the study contributes to more sustainable change: the interventions are grounded in the real, historically accumulated tensions of the system, involve all voices in the process, and lay the groundwork for expansive learning and sustainable long-term transformation. While this analysis supports both the researcher and the participant group in the CL process, it is intended to complement—not replace—the joint analysis and discussion during the sessions, which are essential for jointly reconstructing contradictions within the activity system.

This study has limitations. First, the qualitative analysis relied on semi-structured interviews that were typed in real-time rather than audio- or video-recorded, which may have impacted the depth and richness of the data collected, potentially limiting the capture of nuanced verbal and non-verbal cues. Additionally, while the analytical framework based on Engeström and Sannino’s approach was applied rigorously, the absence of intercoder reliability checks or formal consensus-building methods may affect the credibility and replicability of the coding process. The use of basic tools such as Excel for data organization, although practical, may also be seen as rudimentary, potentially limiting more sophisticated qualitative data analysis techniques. Nevertheless, this analysis could be meaningfully replicated and adapted in similar cultural and educational contexts to validate and amplify the results.