1. Introduction

According to UNESCO [

1], digital literacy in contemporary society is a necessary skill to understand, interpret, and communicate with the world that is mediated by digital texts. Understanding the mechanics and risks of artificial intelligence is crucial to a confident utilization of key digital technologies and protection from dangers that may arise from these technologies. Digital literacy is necessary to understand not only the products of digital environments but also their underlying principles so that we can protect ourselves and each other as a community from various risks, such as unequal access to information [

2].

Developing a practical toolkit for generative AI usage is a key element in digital literacy [

3], as evidenced by the increasing importance of generative AI as an educational tool in higher education [

4].

In particular, ChatGPT is characterized by its technique of reinforcement learning from human feedback, which incorporates cultural elements and speech patterns that make it difficult to differentiate ChatGPT writings from human counterparts [

5]. In other words, generative AI is no longer a separate domain but part and parcel of human activities. However, this exposes generative AI’s fatal weakness, since it also inherits discriminatory speech patterns, nonsensical information, misinformation, and disinformation as part of human discourse in a phenomenon that is referred to as AI hallucinations [

6].

This study attends to the changes in the students’ perception as they interact with generative AI in higher education. The collaborative process between the user and generative AI mutually develops both parties, requiring the student’s recognition of the necessity and importance of generative AI.

Duong, Vu, and Ngo [

7] explain that ChatGPT has a positive potential to create a collaborative and participatory educational environment insofar as it encourages knowledge sharing and social interactions among students. Students already actively engage in critical explorations of the ethical dimensions of generative AI inside and outside the school. Universities thus have a responsibility to guide students in how to use generative AI and help further their critical explorations of the generative AI’s future [

8].

This study demonstrates how students can expand their writing process through an active selection of generative AI models, training in prompt entry and revision, finalization of AI responses, and its incorporation in their final writing submission. This expansion is especially important, given the current lack of literature on the on-site supervision over the user’s metacritical evaluation. In this age of generative AI, students often utilize generative AI in the preliminary stages of writing to process and summarize information into an organized structure. The future task of humans, then, is to evaluate the AI-written work in progress, regulate and supervise the AI in order to reevaluate and revise their own writing, and determine the final text’s quality as a result of the collaborative process. To address this task, the present study combines three quantitative and qualitative aspects of supervision in higher education: (1) students’ completion of proactive analytical writing, (2) self-questionnaires on their changing perceptions of generative AI, and (3) evaluations of their fellow students’ AI-assisted final writing submissions.

The three main objectives of this study on generative AI usage in higher education centering student perspectives are as follows: (1) analyze how students, after reading texts on critical posthumanism studies, perceive the usage of generative AI in class and in the self-questionnaires; (2) offer samples of AI-assisted student writings and their evaluation by fellow students; and (3) examine how students regard the human–AI collaboration in a posthuman society where generative AI coexists with humans and reflect on its significance.

This study examines how educators might utilize generative AI in their pedagogy for an active and sustainable learning experience in light of growing human–AI interdependence, and how student perceptions of AI change as a posthuman being and learning collaborator. To fulfill these objectives, this study asks three main questions:

- (1)

How do the students interact with AI in a pedagogical design that utilizes generative AI for active learning?

- (2)

How do the students perceive generative AI upon completing their writing assignments in collaboration with generative AI and evaluating generative AI-collaborated essays written by their peers?

- (3)

How do the students perceive AI as an educational collaborator after reading texts on posthumanism, and how might the different levels of perceived difficulty be classified?

2. Literature Review

Generative AI chatbots can function as a tailored educational tool, as it is independent from temporal or spatial restrictions, interacts in real-time, and provides feedback that caters to the specific needs or questions asked by the prompt [

9]. In particular, generative AI with an ability to discuss and debate with humans elicits student-to-student group discussions. By assisting the educator in designing the course, it can improve student participation [

10].

Pedagogical use of digital culture in higher education for students who are “digital natives” can impact how students acquire knowledge and organize their learning process. Students who are used to new technology tend to be more pliable in their thinking and less averse to change. Online collaboration technology is thus key to further cultivation of pliable thinking [

11].

Lisa Payne [

12] argues that, while technology may enhance education, it cannot entirely replace it. Usage of ChatGPT in education risks spreading misinformation and violating academic integrity, and overreliance on it may preempt students from critical thinking and problem-solving while discouraging academic engagement [

4]. Nevertheless, students who are familiar with generative AI today experience its various benefits as they proactively participate in academic learning. Students utilizing ChatGPT find its functionalities interesting and express high levels of satisfaction, as shown by studies on ChatGPT, which has received the most scholarly attention among the existing generative AI models [

13]. Studies have also shown that ChatGPT tends to reduce students’ anxiety by eliminating fear related to unsolved problems [

14].

Existing literature on generative AI falls into two main groups, both of which take ChatGPT as their prime model: one which utilizes ChatGPT to analyze publications as a database [

10,

15,

16] and one in which the author embodies a student in a simulation of utilizing ChatGPT [

3,

17]. The former group analyzes existing secondary literature, student training, and self-questionnaires to examine the advantages and disadvantages of generative AI usage, its impact on student engagement and assessments, and limitations on AI-assisted course designs. Generative AI has demonstrated its strength as an educational tool, in particular, in fields such as pharmacology and engineering, and professional licensing examinations [

15]. The latter group is interested in educational methodologies or the significance of using ChatGPT, focusing on AI’s assistance in course designs. Studies in this group explain that, while generative AI in higher education still has ethical issues such as academic integrity, equity, and accessibility, its significance as a “digital colleague/collaborator” may warrant a reevaluation if used responsibly and constructively for enhancing digital literacy [

3]. The ability to coexist and collaborate with generative AI as it evolves at a much higher speed than humans can adjust is a key component in digital literacy [

18,

19].

As the educational usage of generative AI becomes commonplace, students reflect on the AI’s impact on humans’ creativity, authenticity, and autonomy beyond its use as a writing tool. They confront the uncertainty about what kind of future AI technology might bring and endeavor to use the technology both critically and ethically [

8].

Through lectures on posthumanism, students were introduced to artificial intelligence as both an augmentation of human capacities and a site of critical reflection on creativity, authenticity, and autonomy. Boström [

20] explains that human being transforms from “human” (present humanity) to “transhuman” to “posthuman,” where the posthuman at the end is no longer the same human but an entirely new being. Nevertheless, technologies, such as body modification and mind uploading, that are endorsed by transhumanism also raise existential and ethical questions around human identity. Furthermore, as scholars of critical posthumanism point out, developments in science and technology are inseparable from a capitalist logic that generates a new class hierarchy, which raises questions around justice and equity.

Meanwhile Rosi Braidotti [

21] claims that humans are already posthuman. Insofar as human death transforms the human body into nonhuman and nonindividual inorganic matter, the human already encompasses the possibilities and vulnerabilities of death. Humans always coexists with various beings, such that human and nonhuman beings are in a relationship of coevolution [

22].

Lindgren [

23] cautions against the naturalization of existing dominant views and hierarchies in AI discourses, emphasizing the role of critical analysis that questions the social and political affirmations of innovation, progress, control, and efficiency.

This study draws the concept of perceived difficulty from Spagnolo, C. and Saccoletto, M. [

24] in its examination of the students’ changing perceptions of generative AI. Students can experience a range of challenges based on their individual characteristics (such as abilities, knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes) and the specific characteristics of the task (such as the text or the mathematical content involved) [

25]. While the question of actual difficulty and perceived difficulty in mathematical tasks may be different from the those inquiries typically pursued in the humanities, Spagnolo and Andrà’s [

25] studies remain useful insofar as they provide evidence on the extent to which perceived difficulty is a significant factor in the student’s learning experience. From a theoretical standpoint, perceived difficulty highlights that affective factors such as individual beliefs, emotions, and attitudes all play an important role. These affective factors include perceived competence, i.e., students’ self-evaluation of their capabilities and proficiency on a subject, and metacognitive experience, i.e., effort allocation, time investment, and judgments of learning during their task-solving process.

As is characteristic of the humanities, students participating in this study demonstrate varying degrees of competence, depending on their everyday reading volume, previous familiarity with generative AI, and various cognitive strategies. Generative AI can help reduce the students’ perceived difficulty of the task, and enable metacognitive regulation that facilitates mutual communication between the student and AI. In consideration of these, this study divides the students into three types based on their perceived competence, metacognitive regulation, and affective factors. To improve the students’ perceived competence, this pedagogical design began with lectures on posthumanism, students’ self-directed writing assignments, and peer discussions. This process helped improve metacognitive regulation so that the students grasped the actual difficulty of the task more accurately in relation to their level of understanding. Certainly, as Spagnolo, C. and Saccoletto, M. [

24] point out, for some students, affective factors such as individual beliefs, self-esteem, and emotions may have a negative influence in increasing the perceived difficulty of the task. Accounting for these cases requires a complex pedagogical design that incorporates a range of methods, including flipped learning, lectures, peer discussions, student presentations, and logistical guidance on how to generate AI prompts.

3. Methods

This study aims to explore continuous and proactive learning strategies using artificial intelligence in The posthuman era through general education at K University in Korea, and to understand university students’ perceptions of generative AI as collaborators. To understand what artificial intelligence means as a collaborator, students first engaged in an in-depth study of posthumanism. Subsequent surveys and peer evaluations were revised and supplemented based on the input of four advisors, including researchers in related fields and a statistical expert. The evaluation and survey items for this study were developed through consultation between the principal investigator and a co-researcher, both of whom hold doctoral degrees and have experience conducting survey research. Reference was made to surveys and classification methods from credible research institutions, such as the Korea Foundation for the Advancement of Science and Creativity’s “A Study on how to apply AI education to K-12” [

26], as well as previous studies on Korean university learners’ use of AI [

27,

28]. After a final round of discussions, the detailed items were organized into a framework.

3.1. Research Participants

The participants in this study comprised 100 students in two separate sections in the fall semester of 2023 and one section in the fall semester of 2024, all of whom were enrolled in the course entitled “Interpreting Masterpieces and Cultural Content.” The course was open to undergraduate students in all academic years and disciplines. Both the peer evaluations and questionnaires were administered on the same date, both on a basis of voluntary participation. In the peer evaluations, all participants had gained an experience in working with AI for their writing assignments by the end of the course. All questionnaires and peer evaluations were conducted outside regular class hours at the end of the semester, after the final evaluation of writing assignments completed with reference to the chosen generative AI tools.

The subjects of this study and the basis for the evaluation were referenced from the research of Noh, D. W. and Hong, M. S. [

29]. Accordingly, learning experiences utilizing generative AI are presented as experiences of participation, thinking, and reflection. The experience of participation refers to gaining experiential knowledge by applying AI to solve real-life tasks. This study asked students to utilize generative AI throughout the writing process, from information gathering to thematic exploration to essay composition. The experience of thinking involves students exercising agency to achieve their desired goals by practicing critical and collaborative thinking skills. This study incorporates generative AI into a pedagogical model, where this study encourages interaction not only between the instructors and the students, but also among the students as peers and between the students and AI. The experience of reflection entails students continuously reviewing, interpreting, and understanding their thoughts and experiences, including self-observation and peer feedback. This study instructed students to keep a journal of ongoing reflections, where they compared, analyzed, and reinterpreted their thoughts vis-à-vis AI-generated responses. The course was designed to incorporate these perspectives, and this study considered the 100 participants who were actively engaged in class to be suitable subjects.

3.2. Research Procedure

In this study, the materials were distributed to participants who voluntarily agreed to participate in the peer evaluation and survey. During the first week of the semester, after the overall course introduction, students were informed in advance that the survey and peer evaluation of those wishing to participate in the study would be referenced in this research, and that students who did not wish to be associated with the study had the right to choose not to enroll in the course. This gave them the freedom to select courses accordingly. Furthermore, even after choosing this course, the research was kept strictly separate from the class, and participants were informed of their right not to take part in the study if they did not wish to. It was repeatedly emphasized that there would be no academic or course-related disadvantages to students who chose not to participate in the research. Rather than having the researchers themselves explain the background and purpose of the study, a staff member from the university’s Center for Teaching and Learning Development (who was not involved in the course) explained it directly to the participants, and the same explanation was included in the consent form. Peer evaluation forms and surveys were distributed after class in a reserved lecture room to which participants moved. After completing the forms, the participants were instructed to place them in the provided envelopes, seal them, and deposit them in a survey collection box outside the lecture room.

3.3. Evaluation Criteria and Analysis Methods of the Study

- 1.

Peer Evaluation Scale for Writing Using Generative AI: Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “excellent” to “very insufficient.” The criteria listed in the peer evaluation scale were also applied identically to the evaluation of assignments by students, who were the subjects of qualitative research; after selecting the relevant assignments, an analysis was conducted.

- ➀

Topic and Question (prompt)

Whether the main topic is included in the question posed to generative AI;

Specificity of the criteria, scope, and content of the question;

Implementation of topic exploration through follow-up questions.

Distinguish between the student’s writing and the generative AI’s response in your description;

Ensure accurate information identification and notation;

Maintain consistency in problem awareness.

Logical structure between the student’s writing and the generative AI’s responses;

Completeness of the composition;

Effectiveness of communication in writing using generative AI.

- ➃

Evaluator’s supplementary comments regarding revisions made by the student.

- 2.

Questionnaire on Students’ Perceptions of Using Generative AI in Writing

Perceptions of the convenience and helpfulness of generative AI;

Frequency of prompt use;

Reasons why generative AI is considered useful;

Perceptions of whether generative AI should be utilized in university courses and the reasons for this view;

Elements necessary for the effective use of generative AI in university courses;

Appropriate ways to use generative AI in academic settings (with consideration of writing ethics);

Open-ended description of personal impressions after engaging in writing activities using generative AI.

The survey was conducted to measure how students’ perceptions of generative AI changed after posthumanism education. The purpose of this survey was to give students an opportunity to gauge and reflect on the degree of their perceptual changes before and after utilizing generative AI in class. All elements were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Not at all” to “Very much so,” and the descriptive questions served as a basis for qualitative analysis of learning effects by allowing the direct voices of the students to be considered.

The data collected for this study were systematically categorized and analyzed using the R statistical program. With informed consent, students’ performance on study materials was compared anonymously to ensure confidentiality. Furthermore, the study investigated approaches to utilizing generative AI, examined the impact of prompt variation on writing outcomes, and analyzed open-ended survey responses through an inductive approach. To provide a comprehensive interpretation, particularly in the analysis of students’ assignments, a mixed-methods design was adopted, integrating both quantitative and qualitative strands of inquiry.

This study adopts a mixed-methods approach following the methodology of integration proposed by Fetters, Currey, and Creswell [

30]. This study collected both quantitative and qualitative data in the student questionnaires, and combines these two sets of data to gain further insight into the students’ thought process during and after their collaboration with generative AI. The two sets of data shed light on the students’ qualitative interpretation of the assignment, generative AI’s significance, and their relationship with AI, on one hand, and the students’ statistical evaluation of their own and their fellow peer writing assignments, on the other. Adopting such a mixed-methods approach allows us to track the qualitative changes in the students’ perception of AI that are not readily visible in quantitative data analysis, maximizing the respective strengths of qualitative and quantitative approaches.

In the student questionnaires on generative AI, the average locates the mean of data. This study organized the data into a Likert scale of 5 points from 1 point (‘strongly disagree’), 2 points (‘disagree’), 3 points (‘neutral’), 4 points (‘agree’), to 5 points (‘strongly disagree’). IQR is another indicator of data dispersion, which is a differential between Q3 (upper 25%) and Q1 (lower 25%). Boxplots are used to visualize the dispersion of data, including the IQRs, quartiles, and the outliers.

The qualitative research consisted of two parts. In the first part, students were asked to write descriptive responses in the peer evaluation and questionnaire, which this study analyzed by theme. The second part asked students to use generative AI to analyze literary and film texts with posthumanist themes. For this second task, ① the instructor used a template based on the taxonomy method, and ② students submitted writing assignments, which included the prompts they submitted to the AI, the AI’s responses, and essay text that combined human and AI-generated writing, a reflection on using generative AI. The second task aimed to comprehensively assess the students’ changing perceptions of posthuman objects before, during, and after using generative AI.

4. Results

4.1. Perceptions of Generative AI in Student Activities Subsection

Following the lectures, students individually analyzed and discussed in class two Korean short sci-fi stories entitled “About My Space Hero” [

31] and “Old Agreement” [

32]. The following is an excerpt from a student’s (“K”) analysis:

In

Table 1, K’s interpretation of the “post-“ does not refer to chronological posterity but to a critical approach of deconstruction and reinterpretation. K explains that what we often presume to have “universal” values or to be “average” humans may not be universal or unchanging. K’s suggestion that the standards of “average humans” must change in the posthuman age is not merely an accommodation of the passage of time but a reflection on our humanity’s future on a more fundamental level. Following this lecture, K showed improved cognitive ability for reflection on posthumanistic thinking and demonstrated academic achievement by connecting this to real-world issues, such as the oppression of Muslim immigrants and transgender people at the 2024 Paris Olympics.

K arrives at a posthumanist conclusion, that humans on Earth must recognize that they are not owners but mere cohabitants, and that they must find ways to coexist with nature. Furthermore, K asserts the author should have articulated her criticism more forcefully against humans who do not critically reflect upon themselves. K shows metacognitive results, in which personal beliefs and values influence problem-solving following self-directed learning.

Following the lectures on posthumanism and the literary analysis assignment, students watched a film called

Transcendence [

33], in which humans and virtual humans come into conflict. In this posthuman age, as generative AI transitions from a useful tool to an everyday companion, the film presents an opportunity to reflect on the human–virtual human relationship.

This study distributed directions and guidelines on how to use generative AI. These guidelines included that students regard generative AI not merely as a tool for information retrieval but as a virtual interlocutor and an equal partner; that they must first individually write a film response without the assistance of other students or AI before they engage with generative AI; that they input at least three prompts; and that they highlight the parts citing AI’s responses in the final writing submission. The

Table 2 below provides a few excerpts from an interaction between generative AI and student “L”.

In prompt 1, L describes the rationale behind the question; ChatGPT agrees with L’s question and praises it. Afterwards the generative AI summarizes the prompt’s core ideas, demonstrating a tendency to answer the prompts deductively. This is particularly helpful for students who are not able to grasp the core idea of their own prompts. Additionally, recent generative AIs have begun to end their lengthy response with a summary of their own response. These changes are helpful to students who are more used to short-form writings, such as a list of headlines or short-form news clips, by helping them review the core ideas in their individual study.

Although only select parts of the assignment are presented here, students discussed a wide range of themes, including other themes of the film not directedly related to posthumanism or to the coexistence of humans and AI. Overall, students demonstrated consistency in their critical attention to the issue of posthumanism and AI at hand. As seen in the reflection, student L showed a strong affinity for generative AI, expressing positive feelings such as “enjoyable” and “new and interesting.” L’s curiosity and interest made for a sustained interaction with AI in completing the assignment, as it enhanced their metacognitive regulation and lowered their perceived difficulty of the assignment.

Another recent feature of generative AIs is a tendency to return a question, asking the prompter’s opinion at the end of the response. There is an algorithm set in the AI to ask, “What do you think about [topic]?”, as shown in the bottom of Response 1. While many students began the interaction with the premise that the AI was an interlocutor, they said questions like this still took them by surprise. As students are more used to accepting the AI’s responses passively, returning a question to the prompter helps them to remain more alert and proactive in their learning process. The generative AI praises the prompter’s opinion in Response 2, increasing the prompter’s confidence to continue the exchange.

Table 3 shows how Y tries to understand some of the questions raised by the film that remained unanswered after the student-to-student discussion in class by interacting with generative AI. Many students who completed the assignment wrote their prompts about parts of the film they found ambiguous and accepted the AI’s responses as is. By contrast, Y prompts the AI to embody the film’s character and identifies the relationship between humans and AI in the response’s logic in a metadiscursive way. Not only is the film expressly concerned with themes of posthumanism, but Y draws an equivalence between the film’s Will, a virtual human, and the generative AI, an artificial intelligence temporarily embodying the film’s settings. As shown in the format of

Table 3, the assignment differentiates the text by author to explore if and how the distinction between humans and AI are articulated in the students’ interaction with AI.

Because the film’s character (Will) traverses the border between human intelligence and virtual artificial intelligence, many students expressed confusion around Will’s identity as both human and AI. Y asks the generative AI who signs off on one’s actions and who makes those decisions. The AI, temporarily embodying the film’s character (GPT_Will), is consistent in grounding its responses on reason and logic rather than on emotion. Even when Y asks whether it is human or AI, GPT_Will responds that it is a machine and artificial intelligence. What is noteworthy is the student identifies emotion as the barometer by which humans can be differentiated from AI. For the student, GPT_Will’s response, that it has “the emotional depth and capacity to understand human experience ‘like a human’,” lacks specific evidence or interpretation. Its interpretation, that it will “feel a deep sense of loss at the wife’s death in the film,” likewise reads like a standardized response that has been previously trained. According to Y, GPT_Will furthermore is not put off by questions probing at Will’s intimate relationship with the wife or his/its private emotions, providing instead commonsensical responses that are based less on sensibilities of devotion or love than on logical reasoning. GPT_Will asks in turn whether Y recognizes GPT_Will as artificial intelligence or an entity with an autonomous identity similar to humans. In the final writing submission, Y concludes that humanness without emotion is mere information, and that virtual humans ought to be regarded as an entity outside the parameters of the human.

Student Y, for instance, was well-read and demonstrated exceptional critical thinking skills based on their extensive debate experience. While other students found AI useful for providing the best possible responses, student Y, even when they had a lower perceived difficulty of the assignment compared to others, was wary of relying on AI to complete the assignment. As shown in their personal reflection, student Y contested that AI was not infallible, and that there was a clear boundary between humans and nonhuman AI.

4.2. Student Questionnaires on the Perception of Generative AI

4.2.1. Changes in the Students’ Perceptions of Generative AI

A survey was conducted at the end of the semester, after all courses had concluded, to assess changes in students’ perceptions of generative AI.

Table 4 below presents the finding regarding whether students actually found generative AI to be useful after using it.

As

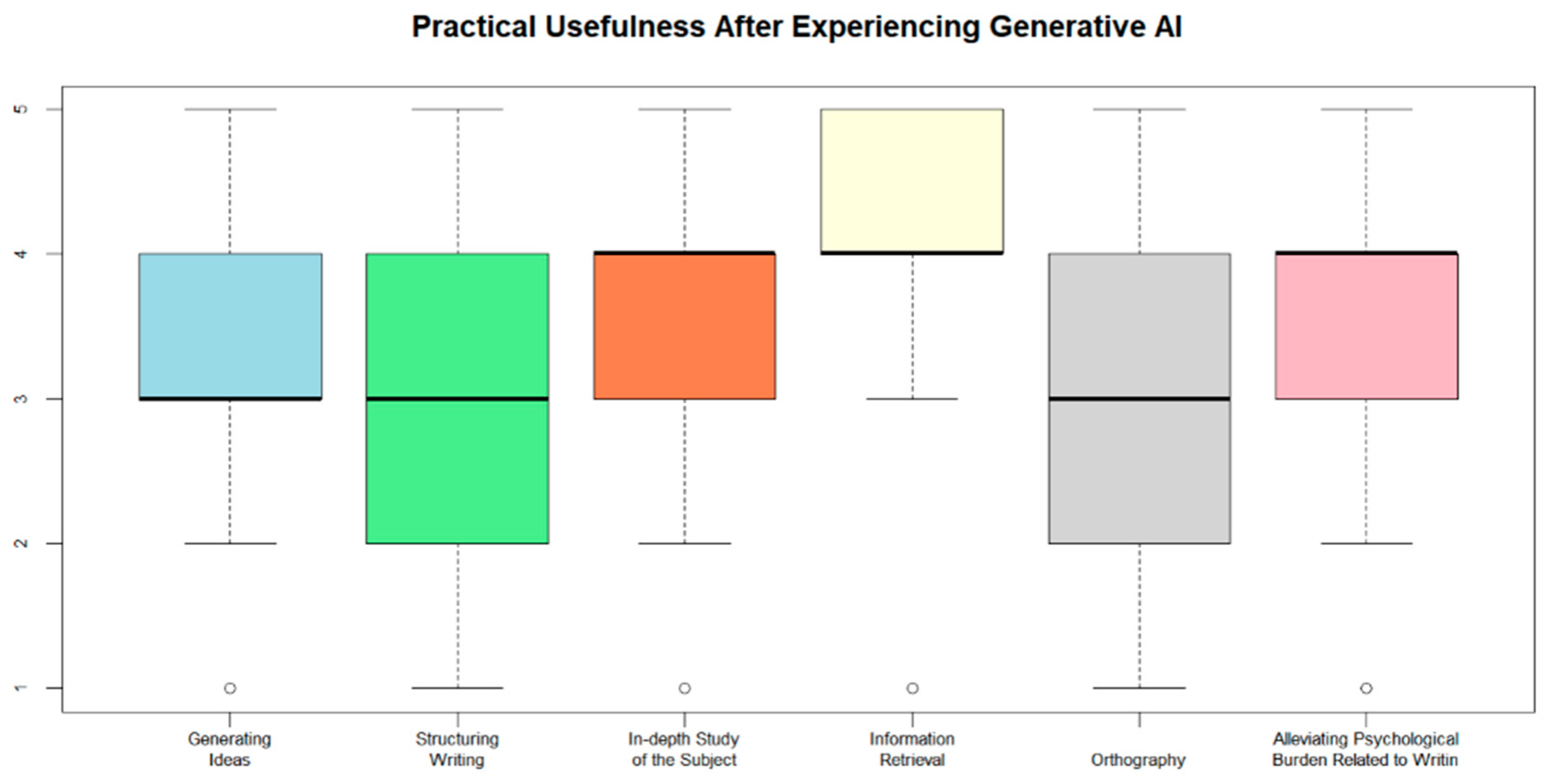

Table 4 shows, the questionnaire divided the AI’s utility into six sub-categories. The average was 3 points or above across all sub-categories, indicating that students found AI to be useful in said sub-categories. In this quantitative analysis of the questionnaire, most participants evaluated the “information retrieval” (4.30) function most positively and uniformly. Here, the average value exceeded 4 points, and both the standard deviation and IQR were low, suggesting that students found AI’s information retrieval function to be both immediately useful and comparatively easy. Students tend to perceive tasks with higher cognitive loads as more difficult, which affects learning efficiency.

As shown in

Figure 1, “orthography,” which had a low average of 2.97, showed a relatively high standard deviation and a wide IQR, but no significant outliers were found. This suggests students experienced a range of perceived difficulties and cognitive burdens during the learning process. This range may stem from differences in the students’ background knowledge of grammar and their general writing abilities, resulting in a variety of opinions regarding the utility of generative AI in correcting their orthography.

Looking at their reflections on the experience of using generative AI, responses such as “[g]enerative AI provides more accurate information than when I communicate with people,” “I liked that it saved the time needed to search for materials,” and “[i]t was nice to be able to receive a variety of opinions instantly” suggest that students found AI to be useful, efficient, and comprehensive in information retrieval. Given their positive assessment of information retrieval, it can be inferred that information retrieval presents the highest cognitive load in students’ completion of the writing assignment and that AI provided opportunities to reduce this load.

According to

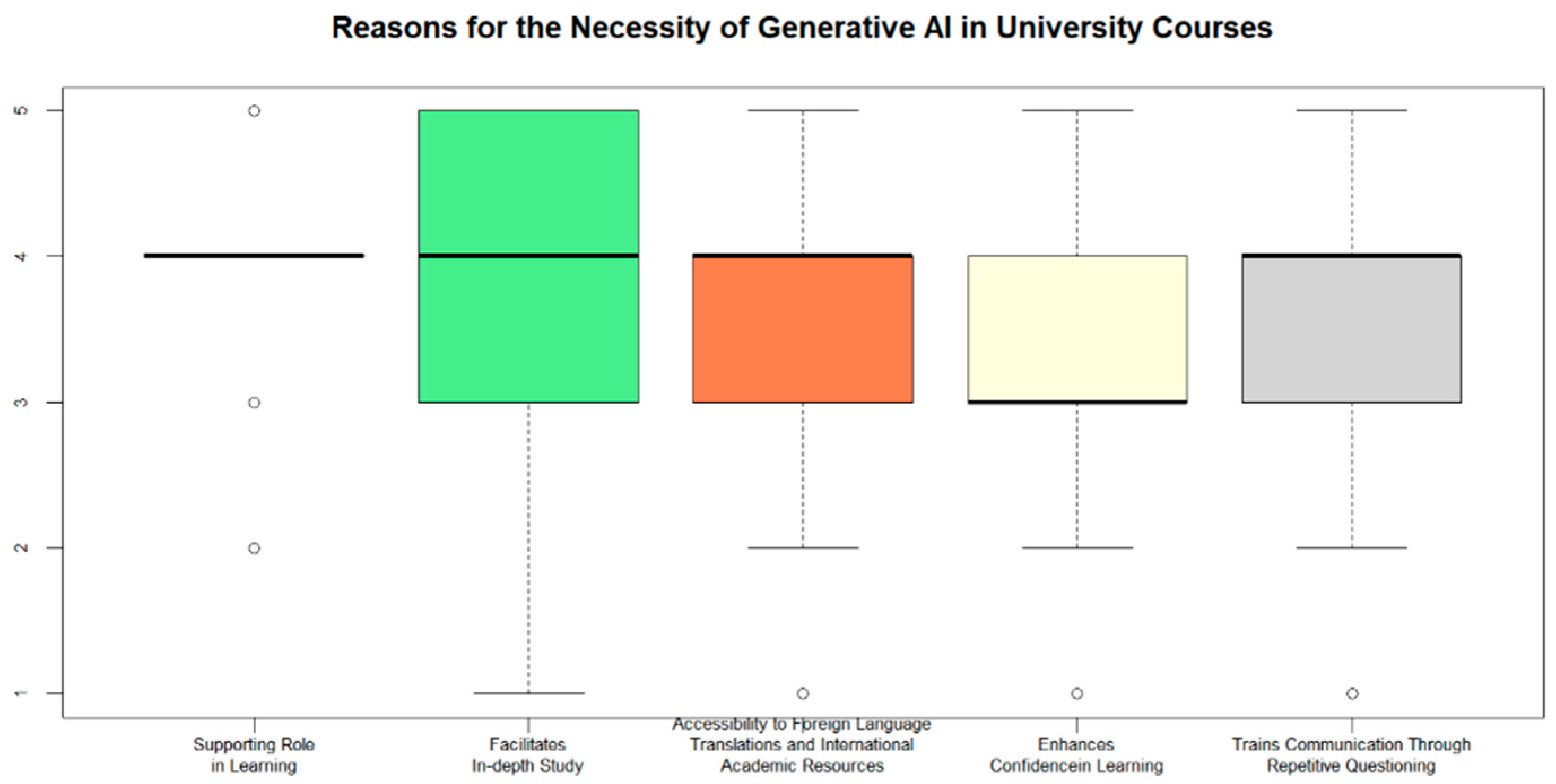

Table 5, regarding the necessity of using AI in university courses, students indicated a generally positive answer, as average values for all categories were above 3. In particular, the category “Supplementary Role in Learning” (4.16) had the highest average among all categories, with a standard deviation of 0.574, which was significantly lower than that of other categories, and an IQR of 0. This means that most respondents strongly recognized the necessity of generative AI in terms of its supplementary role in learning. Regardless of the students’ individual background knowledge or capabilities, they commonly recognize the utility of generative AI as a supplementary role in university courses.

According to

Figure 2, although the result for “Enhanced Confidence in Learning” (3.25) shows the lowest average value, it suggests that affective factors here play a significant role in shaping the perceived difficulty of tasks, as students gave similar assessments to categories such as “Facilitates In-depth Study” (3.65), “Accessibility to Foreign Language Translations and International Academic Resources” (3.64), and “Trains Communication Through Repetitive Questioning” (3.60).

Students responded that “[w]hen used as a means of assistance, I felt it actually led to more active and creative outcomes,” and “[b]ased on the answers, I was able to delve deeper and further enhance my learning.” These responses indicate that, through the use of AI, students’ metacognitive regulation improved, allowing them to discern that their thinking had expanded and deepened during the process of using AI. In addition, some responses included future-oriented reflections, such as “I feel that using generative AI will be necessary for my future.”

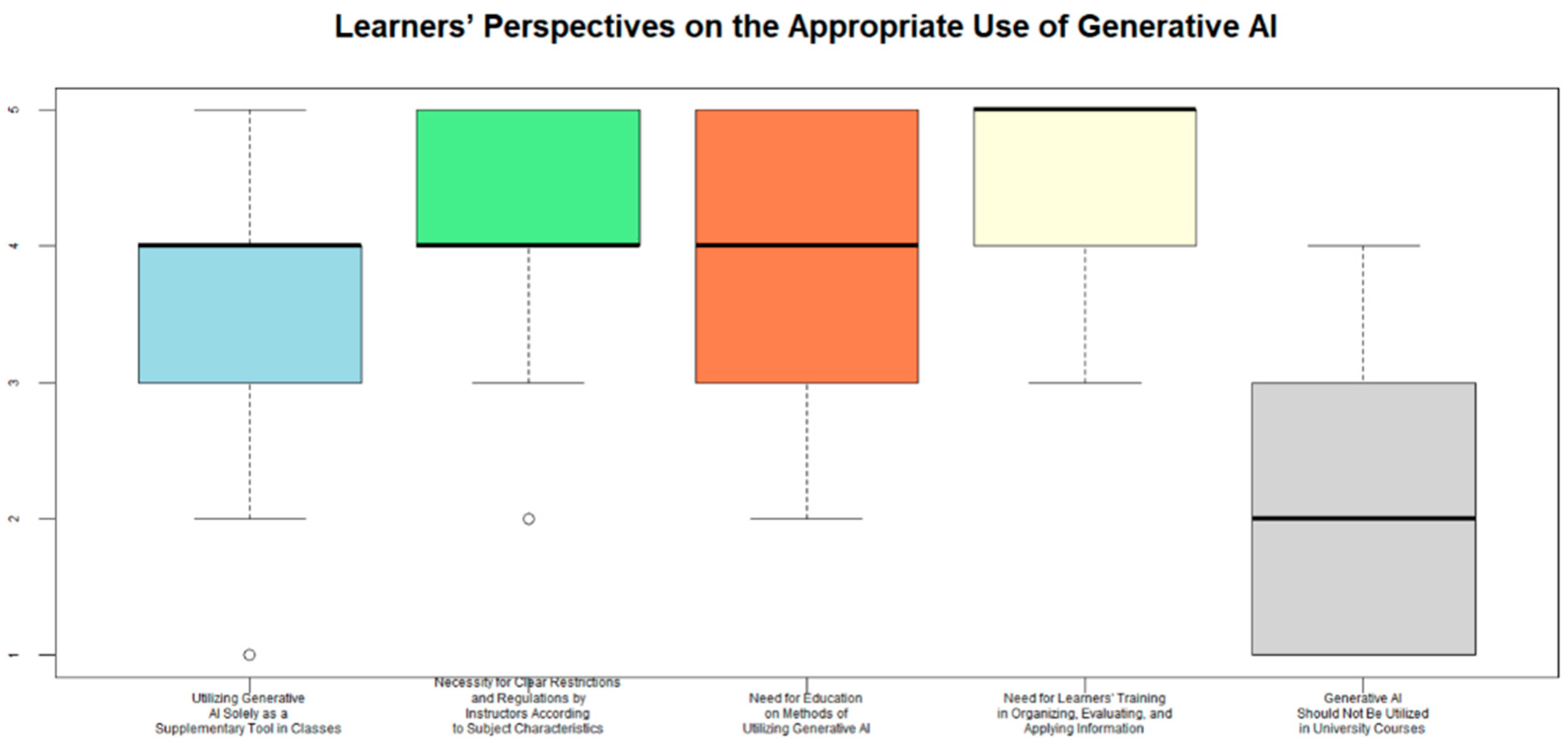

Table 6 presents the categories regarding the different functions of generative AI, “Need for Students’ Training in Organizing, Evaluating, and Applying Information” (4.44) was the category with the highest value; this category also had a lower standard deviation of 0.6233 compared to the other categories. In addition, students also emphasized the “need for utilization methods tailored to the characteristics of each subject” (4.18) and “need for overall education on how to effectively use generative AI” (4.08), indicating that students appreciated the necessity of training and practice for AI to be fully integrated in higher education if it were to serve a role beyond a supplementary tool. The category “AI Should Not Be Used in Higher Education” (1.97) had a lower average, but affective factors, such as unfamiliarity with AI, fear of plagiarism, and difficulties in assessing and editing AI-generated responses, may have played a role in leading some students to think that generative AI is unnecessary. The role of affective factors was also confirmed in questionnaire responses, where students wrote “[g]enerative AI responses are not helpful to me,” “[r]ealizing that generative AI doesn’t suit me is also a valuable experience,” and “[i]t didn’t feel like I was actually learning anything.”

Except for the category “AI Should Not Be Used in Higher Education,” the average value and quartiles for all other categories were 3 or higher, indicating that the majority of respondents (over 75%) rated those categories as at least average. The mean score for the category “Not Necessary to Use in University Courses” was close to 2, and its quartiles were all below 3, suggesting that most students recognized the necessity of generative AI in university courses. This is also affirmed by some of the responses in the questionnaire: “I used to write reports by generating shallow answers from simple or one-dimensional questions with generative AI, but through this course, I realized the importance of in-depth questions and the essential background knowledge required to ask such questions,” and “[i]f I unknowingly ask questions that are incorrectly framed, I might become even more confirmation-biased.” Indeed, regarding this wariness of confirmation bias, one student wrote, “[o]ne drawback is that one can mistake the AI’s thoughts for their own.” This study can infer that students’ metacognition concerning their knowledge and abilities led to a reflection on their own individual abilities and knowledge (“self-considerations”), indicating that students realized they needed to develop their own abilities as a precondition for an effective communication with AI (

Figure 3).

4.2.2. Evaluations of Fellow Students’ AI-Assisted Final Writing Submissions

As a metadiscursive practice, evaluations of fellow students’ AI-assisted final writing submissions help students reflect on their own writing process and their own final product. A consistent usage of generative AI shifts the emphasis in students’ critical thinking skills from information retrieval to assessment of the AI’s responses. Students enhanced their metacognitive regulation abilities through practice and assessment, in a process of drafting the prompt and determining to what extent they will accept the AI’s responses or further engage by inputting more prompts.

A total of 43.8% of students asked three to four prompts to the AI, and 20.5% asked five prompts or more. Those who responded ‘strongly disagree’ or ‘disagree’ asked prompts that reviewed key concepts or asked questions that were unrelated to one another. In the final product, these prompts tended to stop at analyzing key scenes in the narrative or emphasizing the links between basic concepts.

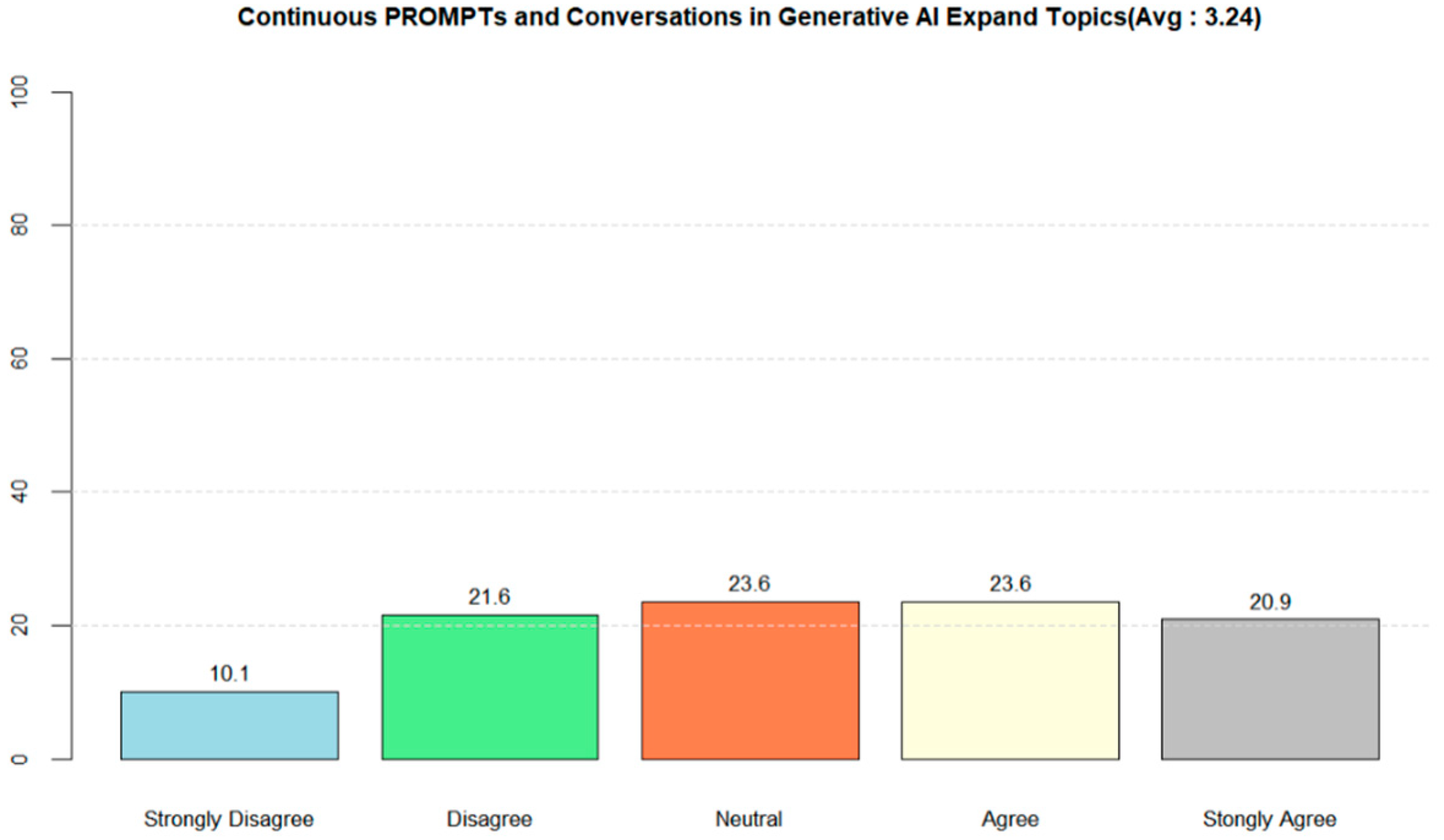

Figure 4 shows that 44.5% of students responded that, the more prompts the students input, the more thematically expansive their final writings became. A total of 23.6% of students who responded ‘neutral’ include cases in which one prompt included several questions.

Over 70% of students responded that they remained consistent in their critical thinking while using generative AI. The students built a critical understanding of posthumanism by reading theoretical texts on posthumanism, as well as analyzing and discussing posthumanism-themed literary and film texts. Having this foundation helped enhance the students’ perceived competence and allowed them to engage in a sustained inquiry of the subject.

A total of 62% of students responded that their final report was sound in logic, while 20% responded that it was not. For additional comments, this study asked: “If the report is in the range between ‘very illogical’ and ‘neutral,’ what kinds of revisions are necessary?” Most students in this commentary wrote that they had included generative AI’s responses without including their own thoughts, implying that they let the AI responses encompass or determine even the parts that should have been written by the students themselves. While students with more consistency in their critical thinking engage and collaborate with generative AI (

Figure 4), those with less consistency complete their final writing assignment by citing AI responses without discretion. In these additional comments, some students also responded that “not everything from AI responses need to be quoted,” “AI responses need to be selectively cited to suit the student’s argument and context,” and that “ChatGPT responses are almost completely superfluous to the assignment.” This can also be inferred as students developing their metacognitive abilities while evaluating others’ writing.

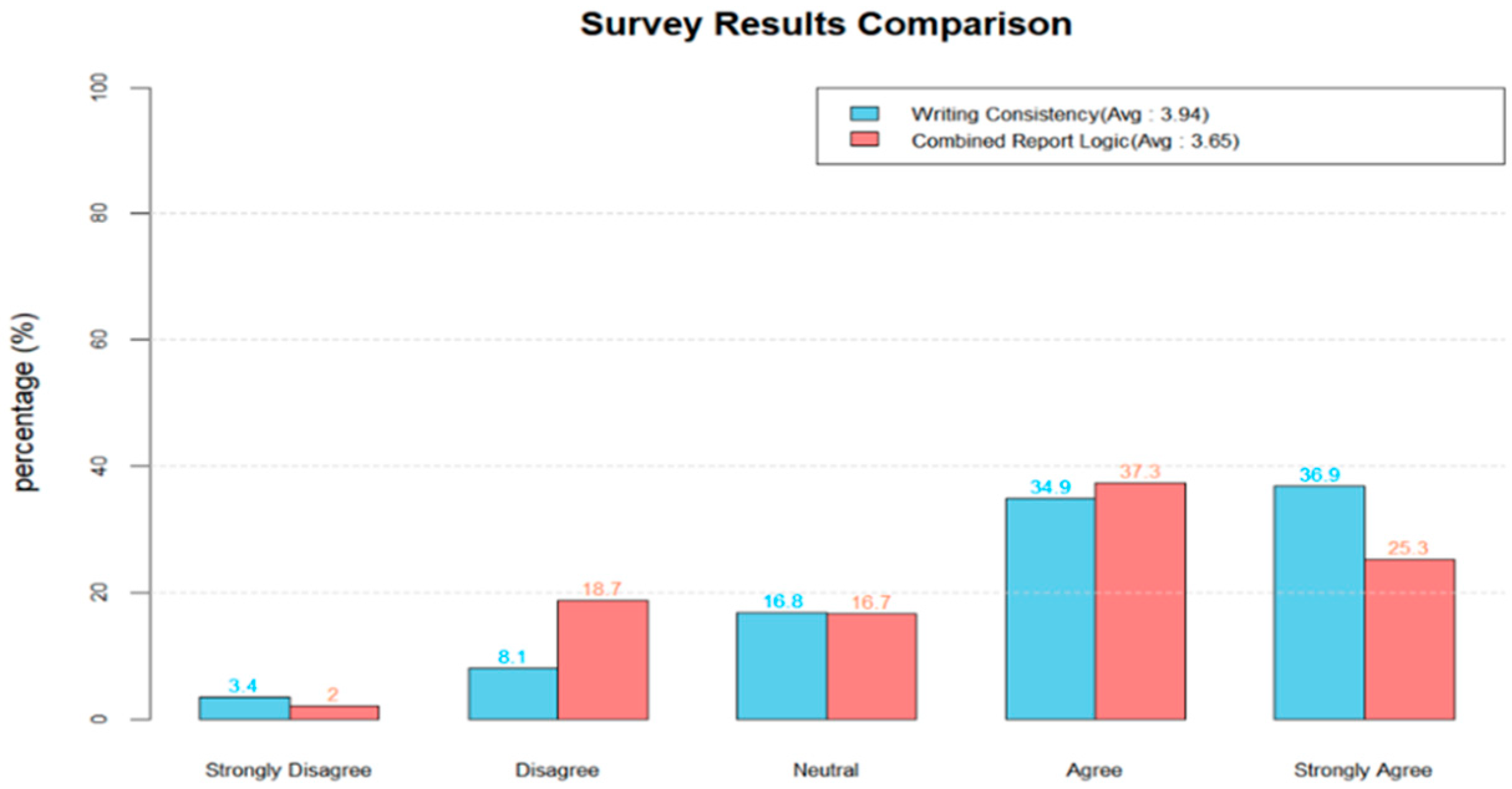

For this reason, in

Figure 5, while 36.9% of students responded ‘strongly agree’ for consistency in critical thinking, only 25.3% responded ‘strongly agree’ for soundness of logic in the final writing report. This difference might stem from cases where the student asked consistently critical questions to the generative AI but was unable to incorporate responses into their final writing submission that would be logically sound. There also might have been cases where the student was dissatisfied with the AI’s responses to cite them in their final report. This also suggests that students who feel cognitively burdened by advanced learning materials may experience lowered perceived competence, leading to an overreliance on generative AI. Conversely, students with higher perceived competence may believe they can complete tasks on their own rather than relying on generative AI.

5. Discussion

Based on the results of this study, which utilized a mixed-methods approach, make three main suggestions.

First, this study suggests more pedagogical models should be devised to facilitate cooperation between the students and AI. Previous literature has described how to train generative AI for educational purposes, which include the strengthening of AI’s reading comprehension and thinking skills [

29], and training it in both the skills and ethics of writing [

34]. Positing the primacy of the traditional modes of education, authors of existing literature have emphasized generative AI as a tool, and thus have focused more on the process of training and using AI than the AI-generated responses. But students intuit the AI’s capacity. This study focused less on training AI than on training students as they design, assess, and repeat their prompts when interacting with AI. As such, while educators and students may have different perspectives on the usage of generative AI, student questionnaires and their fellow student assessments demonstrate that students who frequently use generative AI agree on a need to establish some basic methodology.

At present, the basis for evaluating the AI-collaborated writing is moving from creation to assessment, and from result to process. As generative AI’s development depends on the extent of human feedback and data accumulation, digital capitalism is emerging to make a hierarchy of information between free and paid versions. Educators must tailor generative AI’s usage to the specific course subject while also emphasizing that critical thinking and reading skills remain the basic principles of learning. Students must be made aware that, even when educators incorporate AI, the ultimate aim is to advance and sustain an active learning experience for the students.

This study emphasizes the significance of reciprocity in human–AI communication, and, at the same time, the need to develop a more critical viewpoint toward generative AI based on texts on posthumanism. This study submits that the theme of posthumanism in the lectures and reading materials helped students improve their perceived competence and reduce any affective factors that may inhibit the learning process, such as feelings of uncertainty and anxiety.

The ‘final report’ required students to select, edit, and incorporate AI’s responses in their own writing. This study has affirmed that, while generative AI can help students revise their writing to complete the final report, without a consistent engagement of their critical thinking and writing skills, the final report tends to be mere citations of AI-written responses. The process of collaborating with AI involves two meta-analyses on the student’s part, where the student evaluates the AI’s assessment of its own responses during the interaction and then evaluates a fellow student’s final report, where the fellow student author assessed AI-generated responses.

Second, even when generative AI evolves to communicate and collaborate with students more easily, educators must prioritize developing the students’ critical thinking skills and metacognitive reflection as the foundation of their learning experience.

Through a mixed-methods approach, this study confirmed that the main role of generative AI in the students’ task-solving process was information retrieval. Taking a humanities perspective, the course focused on the philosophical concept of human–AI coexistence and collaboration, and delivered relevant theoretical concepts such as posthumanism. For students whose perceived difficulty of the course ranked high, collaborating with generative AI helped alleviate this cognitive demand in digesting the various concepts in the lectures, as well as developing the themes and improving the quality of prompts for the writing assignments.

Student questionnaires demonstrate that, the more prompts students input, the more likely their thinking expands thematically in the final writing submission. When students input variations in what is essentially the same question in the prompt, they may obtain varying responses from the AI and experience a certain expansion of the range of possible questions they can raise further. Some students have pointed out how the AI responded ambiguously with a tone of “practiced” humanness in their exchange. Constituting the category of ‘interaction with AI,’ students assessed the series of exchanges between the prompts input by their fellow students and the AI responses. From a posthumanist perspective, a majority of the students responded that, while AI provided useful analytical interpretation, it was rather limited compared to human intelligence in providing innovative or unpredictable responses in more creative aspects.

In this regard, the student’s response in the self-assessment that “‘the student’s attitude’ in utilizing generative AI is more important than the AI itself” may be classified as an example of “self-considerations” [

24].

In the student evaluations of their fellow students’ final writing submissions, the strongest category was interaction with AI (3.78), followed by final report (3.62), then topic and prompt (3.52). Students responded that training was necessary for interacting with AI and completing the final report, but their weakest category was in fact a critical understanding of the topic and prompt composition. Ultimately, the student’s thorough understanding and critical reflection on the topic are key to a productive use of generative AI. Metacognitive regulation plays an important role in mediating the student’s reflection and critical thinking.

Third, educators must attend to how varying degrees of students’ perceptions of tasks can influence the students’ apprehension of posthumanism and their attendant perception of AI.

This study asked the students to recognize generative AI as a collaborator and interlocutor in their interaction with it from a posthumanist perspective, rather than as a mere tool. This course enrolled students from various academic backgrounds, including the humanities, social sciences, arts and sports, and science and engineering. This study classified various learning types exhibited by the students based on this study’s analysis of statistical data, writing assignments, questionnaires, and peer evaluations. As can be seen in

Table 4, most students can be classified as cognitive learners, where they mainly utilized generative AI to retrieve information and lower the cognitive demand of the assignment by brainstorming the themes, alleviating writer’s block, and practicing writing prompts. Still, responses such as “while it was convenient to look up and organize relevant literature, it was difficult coming up with prompts and incorporating the AI’s answers into the essay” and “using AI risks confusing AI’s thought as one’s own thought” indicate some difficulties in generating prompts and concerns about over-dependence on AI.

Similar to L, as shown in

Table 2, students expressing a sense of familiarity with generative AI and openness to human–AI collaboration wrote, “it was a strange experience to use a new invention” and that “[i]t was new and interesting to interact and get to know a being different than myself.” The study by Spagnolo, C. and Saccoletto, M. [

24] examines the varying degrees of perceived difficulty of mathematical tasks, where it classifies students who responded that their individual characteristics were key to solving the tasks under “self-considerations.” By contrast, the task for these students was to collaborate with generative AI, a non-human being, in an open-ended process where there was no readily available formula or predetermined answer. Therefore, this study suggests that the perception by students like L must be classified under “metacognitive regulation.” Metacognitive learners are able to articulate what they currently lack or fail to grasp in their communication with AI. They are able to incorporate the responses given by AI, expand their own thinking, and build a good rapport. By contrast, students like Y, as shown in

Table 3, draw a clear line between the human and the nonhuman. They do agree with the view that “humans can add objectivity to their writing by using generative AI. Even if my impressions and reviews [of texts] express my own thoughts and values, generative AI can still be utilized.” At the same time, these students also reveal a sense of aversion to or discomfort in not being able to incorporate AI into their learning and writing processes when they write that “it doesn’t feel like learning” when interacting with AI, and “it feels like an ornament since it doesn’t reach the depth of the individual’s thinking.” This study categorizes these students as affective learners because they criticize the seeming perfection and objectivity of AI, and assert that it is unable to communicate on an emotional level with humans. While they responded that an apparently seamless interaction between humans and AI was a failure, they increased the cognitive demand and did not rule out interacting with AI as a whole. Affective learners perceive the distinction between human and artificial intelligence itself to be an element that enables cooperation between the two. For instance, one student in this category responded as follows: “I think I offered my own opinion before I asked AI and sought only to receive what I expected to receive. I didn’t process the answers given by the AI objectively.” Another student in the peer evaluation recommended the following: “Ask only for information and don’t ask for opinion.” These indicate the dispositions of an affective learner.

6. Conclusions

During and after this study was conducted, generative AI has continued to evolve at an unprecedented pace, ceaselessly transforming before either the instructor or the students can even perceive the changes. Nevertheless, without human assistance, which includes the verification of AI-retrieved information, validation of the AI’s responses, and confirmation of ethical judgments, AI is not able to make significant progress.

This study sought to foster critical perspectives toward human–AI collaboration through lectures on posthumanism, individual textual analyses, considering the student’s perceived difficulty, and student-to-student discussions on human and nonhuman coexistence, as well as its sustainable educational significance. This study directed students to write a first draft of the writing assignment on their own and complete the final report based on their interaction with generative AI. Understanding the students’ perceived difficulties and analyzing the writing process allows for the development of a new perspective, and to expand our thinking on the efficacy of AI usage in education.

As an interlocutor and a learning partner, generative AI is free from temporal, spatial, and emotional constraints, whether it summarizes the student’s questions and asks about their significance or embodies a character within the film to ask the student to define the identity of the film’s virtual human character. Critical analyses of various texts and experiential explorations of generative AI have led some to comment that, while generative AI mimics human emotion and behavior, it still translates those human elements into information. Based on these, this study classified the students’ perceived difficulties into perceived competence, metacognitive regulation, and affective factors.

Students who are cognitive learners recognize that high-level and critical thinking is what allows them to conceptualize and generate prompts that will help produce a thematically consistent and focused piece of writing. Yet some students prioritized the final outcome over the interactive process with AI, leading to final reports that were inconsistent in logic or quality. These were cases in which students passively accepted the AI-generated responses or cited them without modification in the final report. Even if AI-written responses mimic human writing, writing is not a task that AI completes as a proactive writing subject without a human prompt.

In this posthuman age, generative AI will no longer be a passive tool that responds to human prompts, but an interlocutor that explains its opinions to the human and prompts further thinking on the part of the user by answering with a different question. Generative AI models now incorporate emoticons that imply empathy, comfort, and advice in its responses, creating a sense of familiarity to encourage further interaction, especially among the metacognitive learners. This study suggests that, at a moment when the line between human and artificial intelligence is being blurred, students must be deterred from relying excessively on generative AI. At the same time, students, including affective learners who assert that human–nonhuman communication is impossible, should be encouraged to think critically and collaboratively as they interact with generative AI in their everyday and academic life. As in human-to-human interactions, any interaction with AI should be practiced critically so that all students are able to sustain an active learning experience as they draft, revise, and evaluate their writing.

Additionally, it is critical for instructors to collect sufficient data so that they can demonstrate examples of AI-generated responses and final AI-assisted writing submissions to students. Differentiated by kind and degree of difficulty, these examples can have an educational impact when shared with the students. In this study, students were instructed to watch a video that had been uploaded onto the university’s learning management system before they started working on the writing assignment. In the video, this study analyzed both creative and unsuccessful prompts submitted by students from previous iterations of the course. Many responded that this video offered the most helpful guidance in preparing for and completing their writing assignments.

Admittedly, this study draws from a comparatively small pool of select university students in Korea, and focuses on the qualitative aspects of using generative AI. To mitigate these disadvantages, this study adopted an inductive approach, which begins with particular sets of data to draw general conclusions, and a mixed-methods approach. Another challenge in this study was differentiating and classifying sub-categories of the three perceived difficulties. In future investigations of rubric design, we will analyze varying degrees of the perceived difficulty of the assignments so that the classification structure is clear. Future research will focus on how to incorporate student collaboration with generative AI for active learning in class, where the course will focus on AI’s environmental impacts as its theme, especially Green AI-related education for future-oriented citizenship [

35].

This study submits that, in the age of posthumanism, generative AI education requires urgent support from national policymakers and university administrations as an ongoing question of educational philosophy and policy. More specifically, digital educational equality must be ensured at the national level for future citizens to mitigate any digital hierarchy. Just as with Zoom or Google, institutions of higher education should provide universal support so that members can freely access paid generative AI services through official IDs. They should also offer systematic and specific generative AI training not only for the instructors, but also for the students. When utilized in coursework, generative AI must be incorporated as part of advancing educational sustainability by encouraging the students to develop their own AI use guidelines, and exploring ways to foster collaborative learning and critical thinking while minimizing the use of AI.