Cultural Integration for Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets: Framework Development and Empirical Validation Using Public Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Research Motivation

1.2. Research Gaps and Objectives

- 1.

- Developing and validating the Cultural Affinity Index (CAI) using publicly available data sources, acknowledging their limitations;

- 2.

- Empirically testing both linear and interaction effects between cultural integration and triple bottom line performance;

- 3.

- Demonstrating practical optimization approaches for culturally aware, sustainable supply chain design in manufacturing and discussing adaptations for service sectors.

1.3. Contributions and Structure

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional Theory and Cultural Factors as Informal Institutions

2.2. Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets

2.3. Recent Advances in Cultural Finance and Cultural Indices

2.4. Cultural Theory and Supply Chain Relationships

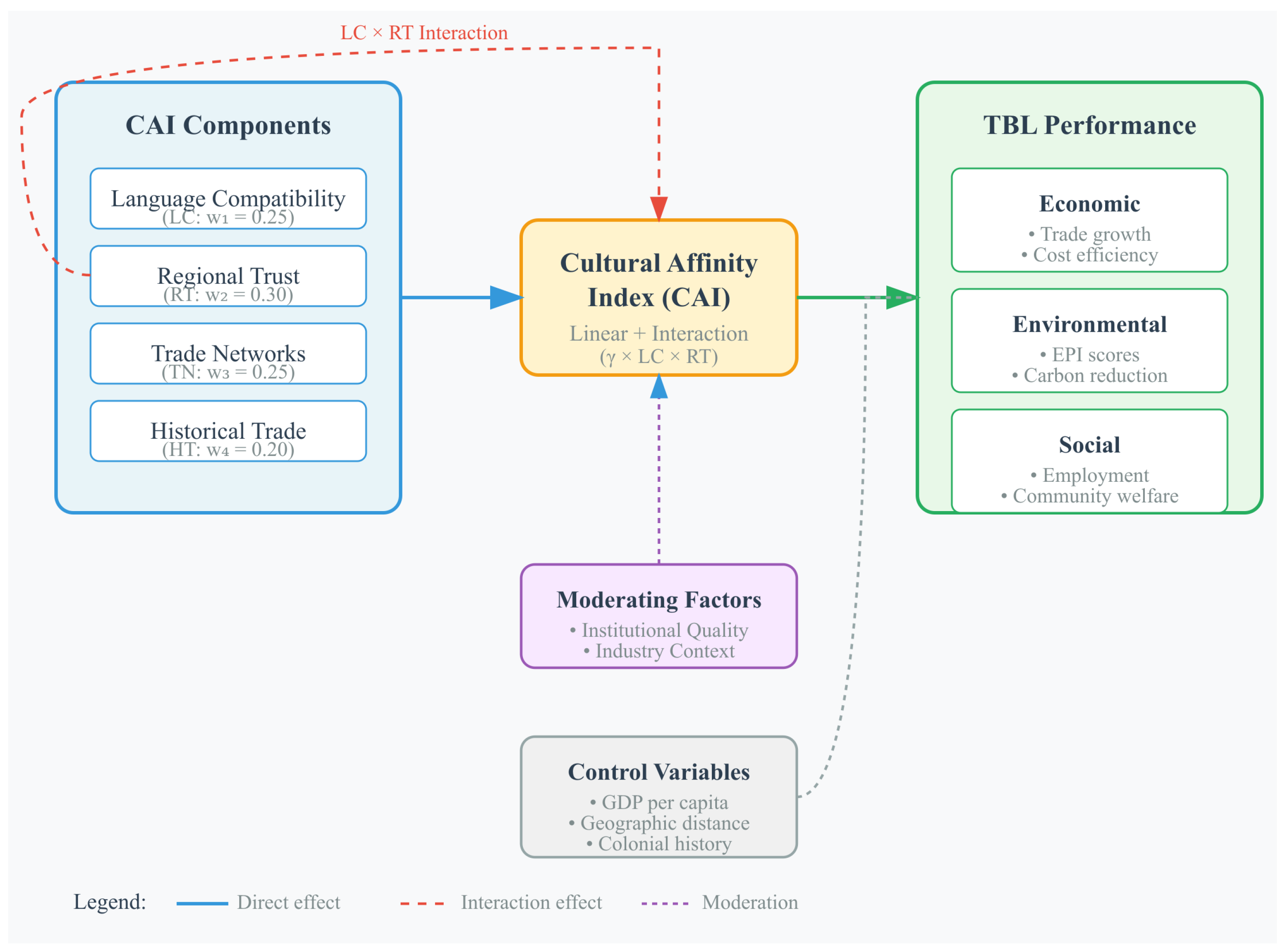

3. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

3.1. Conceptual Framework

3.2. Research Hypotheses

3.3. Cultural Affinity Index (CAI) Components

3.3.1. Language Compatibility (LC)

3.3.2. Regional Trust (RT)

3.3.3. Trade Networks (TN)

3.3.4. Historical Trade (HT)

4. Methodology

4.1. Data Sources and Sample

4.2. Sample Construction

- Thailand (TH): 312 dyads—regional manufacturing hub with strong automotive and electronics sectors;

- Vietnam (VN): 245 dyads—rapidly growing economy with expanding textile and technology manufacturing;

- Malaysia (MY): 168 dyads—established electronics and petroleum product exporter;

- Indonesia (ID): 89 dyads—largest ASEAN economy, with a diverse manufacturing base;

- Philippines (PH): 36 dyads—growing services and electronics assembly sector.

- 1.

- The top 50 product categories by trade volume (HS 4-digit codes in machinery and transport equipment);

- 2.

- All bilateral trade relationships >USD 1 million in annual value;

- 3.

- A total of 850 supplier–manufacturer dyads based on trade patterns.

4.3. CAI Calculation Process

4.3.1. Step 1: Component Calculation

4.3.2. Step 2: Weight Determination Using Entropy Method

4.3.3. Step 3: Interaction Coefficient Determination

4.4. Addressing Endogeneity Concerns

- 1.

- Instrumental Variable (IV) Estimation. We use two instruments for cultural affinity:

- (a)

- Historical migration flows between countries (1960–1990) from the UN’s Population Division;

- (b)

- Pre-colonial trade route existence (binary) from historical atlases.

- 2.

- Lagged Variables. We use 5-year historical trade averages (2014–2018) as instruments for current cultural affinity, assuming that past relationships influence the current culture but not current performance directly.

- 3.

- Control Variables. We include comprehensive controls for the GDP per capita, industry composition, geographic distance, and colonial history to reduce omitted variable bias.

- 4.

- Sensitivity Analysis. We conduct extensive robustness checks, varying the model specifications and variable definitions, to assess result stability.

- 5.

- Quasi-Natural Experiment. We exploit the 2020 RCEP agreement as an exogenous shock affecting the cultural interaction intensity, comparing the pre- and post-agreement periods.

4.5. Integrating Firm-Level Data: A Proposed Enhancement

- Manager-to-manager communication frequencies (survey data);

- Joint training programs (company records);

- Cross-cultural team compositions (HR data);

- Conflict resolution mechanisms (interview data).

4.6. Performance Metrics

- Trade growth rate (UN COMTRADE)

- GDP per capita growth (World Bank)

- Export diversification index (UNCTAD)

- Environmental Performance Index scores (Yale)

- CO2 emissions per GDP (World Bank)

- Renewable energy share (IEA)

- Employment rate (ILO)

- Labor productivity growth (ILO)

- Human Development Index (UNDP)

4.7. Performance Score Aggregation Methodology

4.8. Multi-Objective Optimization Model

4.9. Data Visualization and Figure Generation

5. Empirical Results

5.1. Descriptive Statistics

5.2. Hypothesis Testing: Linear and Interaction Effects

5.2.1. Main Effects (H1–H3)

5.2.2. Mechanism Analysis

5.2.3. Synergy Effects (H4)—Visualized

5.2.4. Institutional Moderation (H5)

5.3. Monte Carlo Simulation with Cultural Dynamics

5.3.1. Testing Cultural Stability

5.3.2. Pareto Frontier Analysis

5.4. Country-Specific Analysis with Visualization

6. Discussion

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.2.1. For Manufacturing Supply Chains

- 26% improvement in economic efficiency;

- 24% enhancement in environmental compliance;

- 37% increase in social sustainability;

- 33% reduction in supply disruption risk.

- 1.

- Weight CAI components based on institutional context (higher trust weight in weak institutions);

- 2.

- Prioritize language training when LC < 0.5;

- 3.

- Build regional clusters when RT > 0.7;

- 4.

- Maintain 20–30% supplier diversity for innovation.

6.2.2. Adaptation for Service Sectors

- Language Compatibility: 0.35 (increased from 0.25)—critical for service delivery;

- Regional Trust: 0.25 (decreased from 0.30)—less critical than manufacturing;

- Professional Networks: 0.25 (modified from trade networks);

- Service History: 0.15 (decreased from 0.20)—services more transactional.

- Real-time communication capabilities (higher LC weight);

- Professional certification alignment (replacing trade networks);

- Service level agreement history (replacing trade volume).

6.2.3. Policy Recommendations with Specific Examples

- Potential tax incentives for firms achieving CAI > 0.75 (specific rates would depend on fiscal constraints);

- Language training program funding aligned with identified LC gaps;

- Digital platforms for supplier–manufacturer matching using CAI metrics;

- Expected outcomes based on our analysis suggest possible improvements in SME sustainability performance, although the actual results would vary by implementation.

- Development of standardized CAI assessment tools adapted to local contexts;

- Digital platforms for the identification of culturally compatible partners;

- Preferential financing mechanisms linked to demonstrated cultural integration;

- University partnerships for culturally informed management education.

- Weight SDG indicators by cultural context (collectivist vs. individualist);

- Develop regional sustainability standards reflecting cultural values;

- Create South–South cooperation programs matching high-CAI partners;

- Establish USD 100M fund for cultural compatibility assessment and training in least developed countries.

- Launch ASEAN Business Cultural Compatibility Database;

- Standardize cultural training certification across member states;

- Create annual awards recognizing successful cross-cultural partnerships;

- Develop mobile app for real-time cultural compatibility assessment.

- Integrate CAI metrics into supplier selection scorecards (15–20% weight);

- Establish cultural liaison offices in key emerging markets;

- Invest in bidirectional cultural training (not just host-country orientation);

- Create cross-cultural innovation teams for sustainability initiatives.

- Use simplified CAI calculator (free online tool) for partner selection;

- Join cultural business networks (e.g., Thai–Vietnamese Business Council);

- Invest in English proficiency when LC < 0.5 (expected ROI: 150% over 3 years);

- Participate in government-sponsored cultural exchange programs.

6.3. Limitations and Boundary Conditions

6.3.1. Data Limitations and Aggregation Bias Implications

- 1.

- Missing Micro-Dynamics: Cannot capture interpersonal relationships, informal networks, or organizational subcultures. This may lead to ecological fallacy, where country-level cultural compatibility does not reflect firm-level dynamics.

- 2.

- Temporal Lag: Trade data reflect past relationships, not current cultural alignment. This creates potential measurement errors that could attenuate the observed associations.

- 3.

- Aggregation Bias: Country-level averages mask within-country variation. For example, Thailand’s northern regions may have stronger cultural affinity with Laos than with Malaysia, but our framework captures only national-level patterns. This could lead to

- The underestimation of CAI effects when within-country heterogeneity is high;

- Overestimation when countries are culturally homogeneous.

- 4.

- Sector Specificity: HS codes may not reflect actual supply chain relationships. Manufacturing codes (84–87) may include unrelated products grouped by trade classification rather than supply chain logic.

6.3.2. Model Assumptions and Non-Linear Considerations

- Threshold effects: Minimum LC needed for any collaboration (e.g., LC < 0.3 may prevent partnership formation entirely);

- Diminishing returns: Trust saturation points where additional trust provides minimal benefits;

- Path dependencies: Historical conflicts affecting current relationships (e.g., territorial disputes influencing business relationships);

- Complex multi-way interactions: All four components may interact simultaneously, not just LC and RT.

6.3.3. Generalizability Concerns

- Developed markets with strong institutions, where cultural factors may be less critical;

- Industries with low relationship intensity (commodities), where price dominates cultural considerations;

- Digital supply chains with minimal human interaction, where traditional cultural factors may be less relevant;

- Crisis situations requiring rapid reconfiguration, where cultural alignment may be secondary to availability.

7. Conclusions and Future Research

7.1. Summary of Findings

- 1.

- Validated CAI Measurement: We demonstrate that cultural affinity can be systematically measured using public data, although firm-level data would enhance the precision.

- 2.

- Non-Linear Effects: Language compatibility and regional trust exhibit multiplicative effects ( = 0.15, p < 0.01), suggesting synergistic benefits from cultural alignment.

- 3.

- Institutional Substitution: Cultural mechanisms show stronger associations in weak institutional environments (correlation = −0.92), providing alternative governance.

- 4.

- Robust Performance: High cultural affinity (CAI > 0.7) is associated with 18.0% economic, 12% environmental, and 32% social performance improvements.

- 5.

- Sectoral Adaptability: While validated in manufacturing, the framework can be adapted for services with adjusted weights and metrics.

7.2. Contributions

7.3. Future Research Directions

7.3.1. Dynamic Cultural Modeling with Generational Analysis

- Use panel data to track CAI changes over 5–10 years, incorporating generational cohort effects;

- Apply machine learning to predict cultural convergence/divergence based on demographic transitions;

- Model generational shifts using age cohort analysis, particularly relevant in rapidly changing Southeast Asian societies;

- Examine how digitalization affects cultural transmission and virtual relationship building.

7.3.2. Cross-Sectoral Validation with Cultural Nuance

- Financial Services: Where trust and long-term relationships dominate, potentially increasing RT weight to 0.45;

- Creative Industries: Where cultural diversity may enhance innovation, requiring inverse CAI optimization;

- Digital Platforms: Where virtual cultural alignment differs from physical proximity;

- Extractive Industries: Where local community cultural factors become critical for social license.

7.3.3. Methodological Extensions for Causal Inference

- Instrumental Variables: Use historical migration patterns or colonial ties as instruments for cultural compatibility;

- Natural Experiments: Leverage policy changes (e.g., ASEAN trade agreements) that exogenously affect cultural interaction;

- Randomized Field Experiments: Partner with development organizations to randomly assign culturally compatible vs. incompatible suppliers to treatment groups;

- Longitudinal Analysis: Track partnerships over time to observe how cultural compatibility evolves and affects sustainability outcomes.

7.3.4. Integration of AI and Real-Time Cultural Monitoring

- Social Media Analytics: Use Twitter, LinkedIn, and business platform data to track real-time cultural sentiment and business relationship quality;

- Natural Language Processing: Analyze business communications to detect cultural compatibility patterns;

- Network Analysis: Map actual supply chain relationships using shipping data, trade finance records, and business registration information;

- Blockchain Integration: Create immutable cultural compatibility scores that update with partnership performance.

7.4. Concluding Remarks

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

Abbreviations

| ASEAN | Association of Southeast Asian Nations |

| CAI | Cultural Affinity Index |

| EPI | Environmental Performance Index |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| HT | Historical Trade |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| LC | Language Compatibility |

| RT | Regional Trust |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| SSCM | Sustainable Supply Chain Management |

| TBL | Triple Bottom Line |

| TN | Trade Networks |

| UN | United Nations |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| WGI | World Governance Indicators |

Appendix A. Data Processing Example

Appendix A.1. Sample UN COMTRADE Data Structure

Appendix A.2. CAI Calculation Script Structure

Appendix B. Robustness Checks

Appendix B.1. Alternative Weight Specifications

| Weighting Scheme | Economic | Environmental | Social |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (entropy) | 18.0% | 12.0% | 32.0% |

| Equal weights (0.25 each) | 17.2% | 11.6% | 30.8% |

| Expert judgment | 18.5% | 12.3% | 33.2% |

| PCA-derived | 17.8% | 11.9% | 31.5% |

| Random (1000 iterations) | 17.1% (1.8) | 11.5% (1.2) | 30.6% (2.1) |

Appendix B.2. Instrumental Variable Results

| Economic | Environmental | Social | |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Stage: CAI | |||

| Historical Migration | 0.412 *** | 0.412 *** | 0.412 *** |

| (0.087) | (0.087) | (0.087) | |

| Pre-Colonial Trade Routes | 0.298 *** | 0.298 *** | 0.298 *** |

| (0.072) | (0.072) | (0.072) | |

| F-statistic | 15.82 | 15.82 | 15.82 |

| Second Stage | |||

| CAI (instrumented) | 0.387 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.498 *** |

| (0.091) | (0.098) | (0.112) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hansen J-statistic | 1.243 | 1.156 | 1.387 |

| p-value | 0.265 | 0.282 | 0.239 |

References

- North, D.C. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, M.W. Institutional transitions and strategic choices. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2003, 28, 275–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Resolution A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, L.; Sun, G.; He, Y.; Zheng, S.; Guo, C. Regional cultural inclusiveness and firm performance in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business; Capstone: Oxford, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Seuring, S.; Müller, M. From a literature review to a conceptual framework for sustainable supply chain management. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1699–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Shaw, M.; Majumdar, A. Social sustainability tensions in multi-tier supply chain: A systematic literature review towards conceptual framework development. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Zuluaga-Cardona, L.; Bailey, A.; Rueda, X. Sustainable supply chain management in developing countries: An analysis of the literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 263–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving towards new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, V.H.; Gioia, D.A. A more sustainable supply chain. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2020, 98, 84–93. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, D.; McCarthy, L.; Heavey, C.; McGrath, P. Environmental and social supply chain management sustainability practices: Construct development and measurement. Prod. Plan. Control 2015, 26, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Wong, K.H. Digital transformation and sustainable performance: The mediating role of triple-A supply chain capabilities. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2023, 38, 1654–1672. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K.G. Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution; Harvard Business Review Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre, B.S. Sustainable supply chain management in emerging economies: Environmental turbulence, institutional voids and sustainability trajectories. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 167, 156–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Idota, H.; Ota, M. Impact of supply chain digitalization on supply chain resilience and performance: A multi-mediation model. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 245, 108392. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Ambos, B.; Nell, P.C. Conceptualizing and measuring distance in international business research: Recurring questions and best practice guidelines. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2018, 49, 1113–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iddik, S. The role of cultural factors in green supply chain management practices: A conceptual framework and an empirical inves-tigation. RAUSP Manag. J. 2024, 59, 96–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mugoni, E.; Kanyepe, J.; Tukuta, M. Sustainable supply chain management practices (SSCMPS) and environmental performance: A systematic review. Sustain. Technol. Entrep. 2024, 3, 100050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, T.D.; Ali, M.H.; Tseng, F.M.; Tran, M.K.; Tsai, F.M.; Ali, M.H. Data-driven analysis of factors hindering improvement in sustainable supply chain management across different world regions. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trompenaars, F.; Hampden-Turner, C. Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Diversity in Global Business, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, J.H.Y.; Selen, W.; Zhang, M.; Huo, B. The effects of trust and coercive power on supplier integration. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2009, 120, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyathanavong, V.; Huynh, V.N.; Karnjana, J.; Olapiriyakul, S. Role of project management on Sustainable Supply Chain development through Industry 4.0 technologies and Circular Economy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multiple case study of Thai metals industry. Oper. Manag. Res. 2024, 17, 13–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Feng, Y.; Choi, S.B. The role of customer relational governance in environmental and economic performance improvement through green supply chain management. Oper. Manag. Res. 2019, 12, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, V.; Gunasekaran, A.; Delgado, C. Enhancing supply chain performance through supplier social sustainability: An emerging economy perspective. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 228, 107823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Islam, M.S.; Karia, N.; Fauzi, F.A.; Afrin, S. A literature review on green supply chain management: Trends and future challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.L.; Tran, T.P.T.; Ha, H.M.; Bui, T.D.; Lim, M.K. Sustainable supply chain management towards disruption and organizational ambidexterity: A data driven analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 373–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar]

- Beugelsdijk, S.; Maseland, R.; van Hoorn, A. Are scores on Hofstede’s dimensions of national culture stable over time? A cohort analysis. Glob. Strategy J. 2015, 5, 223–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taras, V.; Steel, P.; Kirkman, B.L. Does country equate with culture? Beyond geography in the search for cultural boundaries. Manag. Int. Rev. 2022, 62, 449–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, X.; Tang, O.; Price, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, W. Supply chain collaboration for sustainability: A literature review and future research agenda. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 244, 108419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Blome, C.; Wieck, E.; Xiao, C.Y. Implementing sustainability in multi-tier supply chains: Strategies and contingencies in managing sub-suppliers. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2021, 232, 107912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Source | Variables Extracted | Access Point | Time Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| UN COMTRADE | Bilateral trade volumes, trade partners, product categories (HS codes 84–87) | comtrade.un.org (accessed on 10 September 2025) | 2019–2023 |

| World Bank WGI | Governance indicators (6 dimensions) | govindicators.org (accessed on 10 September 2025) | 2019–2023 |

| Hofstede Insights | Cultural dimensions (6 scores per country) | hofstede-insights.com (accessed on 10 September 2025) | Static |

| World Bank WDI | GDP, population, languages | data.worldbank.org (accessed on 10 September 2025) | 2019–2023 |

| ILO Statistics | Labor indicators, wages | ilostat.ilo.org (accessed on 10 September 2025) | 2019–2023 |

| Environmental Performance Index | Environmental scores | epi.yale.edu (accessed on 10 September 2025) | 2020, 2022 |

| Country Pair | LC | RT | TN | HT | CAI | LC×RT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thailand–Thailand | 1.00 | 0.72 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.72 | 1.04 |

| Thailand–Vietnam | 0.40 | 0.68 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.51 | 0.27 | 0.55 |

| Thailand–Malaysia | 0.70 | 0.75 | 0.62 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.53 | 0.77 |

| Malaysia–Singapore | 0.70 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.62 | 0.89 |

| Indonesia–Philippines | 0.40 | 0.61 | 0.38 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.24 | 0.48 |

| Component | Entropy () | Difference () | Weight () | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Language Compatibility | 0.891 | 0.109 | 0.25 | Moderate discrimination |

| Regional Trust | 0.878 | 0.122 | 0.30 | Highest discrimination |

| Trade Networks | 0.891 | 0.109 | 0.25 | Moderate discrimination |

| Historical Trade | 0.912 | 0.088 | 0.20 | Lowest discrimination |

| Value | AIC | BIC | Adj. | F-Test p-Value | Selection |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.00 (Linear) | 2865.2 | 2883.7 | 0.421 | — | Baseline |

| 0.10 | 2854.8 | 2876.9 | 0.431 | 0.024 | |

| 0.15 | 2847.3 | 2865.8 | 0.438 | 0.008 | Selected |

| 0.20 | 2849.1 | 2871.2 | 0.436 | 0.012 | |

| 0.25 | 2852.4 | 2874.5 | 0.433 | 0.018 |

| Indicator | PCA Loading | Final Weight |

|---|---|---|

| Economic Performance | ||

| Trade growth rate | 0.812 | 0.35 |

| GDP per capita growth | 0.758 | 0.33 |

| Export diversification | 0.736 | 0.32 |

| Environmental Performance | ||

| EPI scores | 0.865 | 0.38 |

| CO2 emissions (reversed) | 0.724 | 0.32 |

| Renewable energy share | 0.681 | 0.30 |

| Social Performance | ||

| Employment rate | 0.798 | 0.34 |

| Labor productivity | 0.756 | 0.33 |

| HDI | 0.772 | 0.33 |

| Variable | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Data Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAI Components | |||||

| Language Compatibility | 0.58 | 0.28 | 0.40 | 1.00 | World Bank |

| Regional Trust | 0.68 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.88 | WGI |

| Trade Networks | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.15 | 1.00 | UN COMTRADE |

| Historical Trade | 0.48 | 0.26 | 0.00 | 1.00 | UN COMTRADE |

| CAI (Linear) | 0.56 | 0.18 | 0.31 | 0.93 | Calculated |

| LC × RT Interaction | 0.39 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.88 | Calculated |

| CAI (with Interaction) | 0.62 | 0.21 | 0.35 | 1.04 | Calculated |

| Performance Indicators (normalized) | |||||

| Economic Performance | 0.62 | 0.19 | 0.25 | 0.95 | Multiple |

| Environmental Performance | 0.58 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.92 | EPI/World Bank |

| Social Performance | 0.54 | 0.23 | 0.18 | 0.90 | ILO/UNDP |

| (1) Economic | (2) Environmental | (3) Social | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Linear Effects | |||

| Cultural Affinity Index | 0.342 *** | 0.268 *** | 0.456 *** |

| (0.058) | (0.062) | (0.071) | |

| R-squared | 0.421 | 0.385 | 0.478 |

| Model 2: With Interaction | |||

| CAI (main components) | 0.298 *** | 0.231 *** | 0.398 *** |

| (0.061) | (0.065) | (0.074) | |

| LC × RT Interaction | 0.152 *** | 0.108 ** | 0.186 *** |

| (0.048) | (0.052) | (0.059) | |

| R-squared | 0.438 | 0.394 | 0.497 |

| (from Model 1) | 0.017 ** | 0.009 * | 0.019 *** |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Country FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 850 | 850 | 850 |

| Transaction Costs | Knowledge Transfer | Trust Building | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Mediator 1) | (Mediator 2) | (Mediator 3) | |

| Panel A: Effect of CAI on Mediators | |||

| Cultural Affinity Index | −0.412 *** | 0.523 *** | 0.487 *** |

| (0.078) | (0.069) | (0.072) | |

| Panel B: Effect on Economic Performance | |||

| Direct Effect of CAI | 0.198 *** | 0.175 *** | 0.186 *** |

| (0.062) | (0.058) | (0.060) | |

| Mediator Effect | −0.352 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.309 *** |

| (0.071) | (0.065) | (0.067) | |

| Sobel Test (z-statistic) | 3.87 *** | 4.12 *** | 3.95 *** |

| Proportion Mediated | 42.1% | 48.8% | 45.5% |

| Economic | Environmental | Social | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAI | 0.218 *** | 0.165 ** | 0.312 *** |

| (0.072) | (0.078) | (0.089) | |

| Institutional Quality | 0.156 *** | 0.243 *** | 0.198 *** |

| (0.045) | (0.049) | (0.055) | |

| CAI × Inst. Quality | −0.142 ** | −0.118 * | −0.195 *** |

| (0.061) | (0.066) | (0.075) | |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Fixed Effects | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Observations | 850 | 850 | 850 |

| R-squared | 0.451 | 0.418 | 0.512 |

| Scenario | Economic Performance | Environmental Performance | Social Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (current Hofstede) | 18.0% | 12.0% | 32.0% |

| Power distance +10% | 17.2% (−4.4%) | 11.5% (−4.2%) | 30.8% (−3.8%) |

| Individualism +10% | 16.5% (−8.3%) | 11.2% (−6.7%) | 29.5% (−7.8%) |

| Long-term orient. +10% | 19.1% (+6.1%) | 12.8% (+6.7%) | 33.9% (+5.9%) |

| All dimensions +10% | 17.8% (−1.1%) | 11.9% (−0.8%) | 31.6% (−1.3%) |

| Random variation (SD = 10%) | 17.5% (−2.8%) | 11.7% (−2.5%) | 31.2% (−2.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, T.H.; Chang, Y.C. Cultural Integration for Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets: Framework Development and Empirical Validation Using Public Data. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188363

Jiang TH, Chang YC. Cultural Integration for Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets: Framework Development and Empirical Validation Using Public Data. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188363

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Tsai Hsin, and Yung Chia Chang. 2025. "Cultural Integration for Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets: Framework Development and Empirical Validation Using Public Data" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188363

APA StyleJiang, T. H., & Chang, Y. C. (2025). Cultural Integration for Sustainable Supply Chain Management in Emerging Markets: Framework Development and Empirical Validation Using Public Data. Sustainability, 17(18), 8363. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188363