1. Introduction

Work–life balance (WLB) plays a key role in ensuring employee well-being and organizational effectiveness, while also being an important element of sustainable socio-economic development [

1,

2]. According to the current regulations of the European Union concerning work–life balance, their implementation brings benefits in three key aspects: social, economic, and environmental. In the face of growing professional demands and dynamic changes in the labor market [

3,

4], it is particularly important to understand WLB in the context of rural workers.

Unlike urban workers, people employed in rural areas often face unique challenges, including limited access to flexible forms of employment [

5,

6,

7], long commutes [

8], or combining professional duties with agricultural activities [

9,

10]. The results of Gosetti’s study on the quality of working life among farm workers and agricultural enterprises in the province of Verona (Italy) showed that work more often has a negative impact on their personal lives than vice versa, contributing to potential overload [

9]. The authors emphasize that farmers’ decision-making often involves a trade-off between adaptability and short-term profitability, which sometimes boils down to strategies aimed solely at “household survival,” ultimately “negatively affecting quality of life” [

10].

Against this backdrop, we delineate three core dimensions of work–life balance support that underpin our subsequent analyses: (1) leave, (2) work organization and working time, and (3) occupational health/work hygiene. First, the leave dimension includes care leave, on-demand leave, parental leave, paternity leave, and emergency leave, capturing formal absence solutions that facilitate balance between paid work and private responsibilities. Second, the work organization and working time dimension comprises flexible schedules, remote work, the option to leave work for personal matters, the possibility of bringing a child to work, and adjusting schedules to private responsibilities—practices that directly support everyday role coordination. Third, the occupational health/work hygiene dimension encompasses conditions fostering physical and mental regeneration (quiet workspaces, relaxation zones, additional medical packages, psychological support, subsidized meals, and healthy-lifestyle programs). These categories reflect the socio-economic realities of rural areas in Poland and underpin the variables used in the PCA and clustering analyses.

Studies indicate that different forms of support, such as family and emergency leave, flexible work arrangements, and workplace hygiene solutions, can interact and sometimes act as substitutes [

11]. While leave benefits can support regeneration and work–life balance (WLB), their intensive use may reduce engagement with other regenerative practices and may be negatively correlated with working time flexibility. Demographic factors (gender, age) and employee health status further influence individual perceptions of balance, highlighting the need for comprehensive analysis frameworks.

Employer-offered maternity leave (EOML) shapes a mother’s ability and timing to return to work, affecting her WLB, especially when organizational commitment to WLB is low [

12,

13]. Short leaves limit the time available for self-care and childcare, whereas longer leaves can improve well-being for both mother and child. Flexible work arrangements are widely regarded as best practice [

14].

In Poland, the availability and use of WLB benefits vary by sector, company size, gender, and age [

15,

16,

17]. Older employees and women are more likely to report lower WLB, and declining well-being increases turnover intentions [

12,

18].

Previous studies on WLB in Poland and Europe have primarily focused on urban employees and knowledge-intensive sectors [

5,

16]. Much less attention has been paid to employees from rural areas, who face distinct challenges such as limited access to public services, long commutes [

8], and combining formal employment with agricultural work [

9]. The lack of in-depth analyses in this area represents an important research gap, which the present study aims to address.

Finally, forms of support do not always complement each other; frequent use of one (e.g., leave) may reduce engagement with others (e.g., regenerative activities such as meals at work or employee gyms). Conversely, well-organized work encourages employees to manage their well-being more effectively.

To identify the main dimensions of WLB support and employee profiles, the study employs principal component analysis (PCA) combined with fuzzy c-means clustering, allowing for the capture of complex, multidimensional patterns in work–life balance. Detailed methodological procedures and justifications are provided in the Materials and Methods Section.

The aim of the study is to identify the aspects of WLB support and the relationships between them for rural workers and to define types of WLB based on these aspects. Despite extensive research on WLB in urban contexts, rural employees remain insufficiently studied, particularly regarding the links between different WLB support mechanisms. The aspects of WLB were determined based on variables characterizing available WLB support solutions relating to working time and organization, facilities for combining work and care for dependents, adaptation of leave to employees’ private lives, facilities improving occupational health and regeneration, and support guaranteed by the Labor Code (parental leave, etc.).

Although there are no studies directly addressing the impact of any aspects of WLB on attracting workers to rural areas, studies in cities and knowledge sectors may provide some insights [

19]. The results of these analyses show that access to flexible working hours, family leave, and regenerative support significantly influences the career and location decisions of employees, including young professionals and women [

20,

21,

22]. It is possible that, for example, the introduction of flexible forms of employment in rural areas could contribute to making these regions more attractive to potential employees and employers. The undertaken research has practical significance and responds not only to the needs of employees and employers, but also to migration policy, gender equality, and social cohesion.

Work–life balance (WLB) is one of the key dimensions of employee well-being, and its support in organizations can be implemented through various mechanisms: flexible work arrangements, leave solutions, or health-promoting activities. In the literature, it is indicated that these forms of support may function both complementarily and substitutively, depending on the organizational context and individual employee needs [

1,

2,

6,

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

15,

16,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Based on role boundary theory, the JD-R model, and previous empirical studies on work–life balance, five research hypotheses were formulated, addressing the relationships between WLB practices, employee well-being, and sociodemographic factors.

The following hypotheses were put forward:

Hypothesis 1. Support for work–life balance (WLB) among employees through selected leave solutions (family and emergency leave without time off) is negatively correlated with occupational health solutions (regeneration).

Justification 1. Different forms of WLB support may function as substitutes; using regenerative leave may reduce the use of other practices affecting occupational health [

1,

12,

21].

Hypothesis 2. Support for work–life balance (WLB) among employees through work organization and working time (P) is negatively correlated with support for family and emergency leave solutions (U) 0.417.

Justification 2. Flexible working hours and autonomy reduce the need to use leave [

11,

13,

16].

Hypothesis 3. Support for work–life balance (WLB) among employees through work organization and working time (P) is negatively correlated with support for occupational health (H).

Justification 3. High support in work organization may reduce the perceived need for additional occupational health measures [

11,

18,

21].

Hypothesis 4. Mature employees (aged 35–55) rate their WLB lower, with mature men maintaining a higher WLB than mature women.

Justification 4. Midlife is associated with overlapping professional and family responsibilities, which lowers WLB among women [

2,

6,

15,

19].

Hypothesis 5. As employee well-being deteriorates, the intentionality of changing jobs increases.

Justification 5. Midlife is associated with overlapping professional and family responsibilities, which lowers WLB among women [

2,

6,

15,

19].

Hypotheses H1–H3 from PCA apply to all occupational groups, while H4–H5 from clustering do not apply to farmers.

Some hypotheses apply only to non-agricultural employees because the cluster analysis aimed to identify WLB profiles within wage-earning employees, without distortions caused by the specific nature of farmers’ work.

This study contributes three new elements to the WLB literature: (1) it analyzes the issue in a specific and previously neglected context of rural employees in Poland; (2) it uses PCA and clustering methods to identify WLB types based on multiple support dimensions; (3) it shows how the perception and use of WLB benefits differ across demographic groups. Thus, the article combines a theoretical perspective with practical implications for labor market policy and regional development.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to determine the aspects of WLB support and the relationships between them for employees in rural areas, and to identify types of WLB, i.e., to indicate the main determinants of work–life balance among rural employees. Previous studies in the field of WLB aspect identification confirm that there is no single universal set of aspects, and their selection depends on the theoretical perspective adopted and the socio-professional context of the groups studied. This diversity stems from the fact that WLB research draws on multiple theoretical frameworks—including social cognitive theory, role accumulation theory, conservation of resources theory, and boundary theory—each emphasizing different mechanisms of how work and non-work roles interact [

27]. In addition to the structural approach, which views WLB through the prism of institutional and social conditions—such as work (which builds variables related to professional activity), time (variables related to working time), family (variables related to family condition, including income), health (childcare), and politics (regulations concerning WLB) [

53,

54]—the literature also develops functional, relational, and subjective approaches. The first focuses on the distribution of an individual’s resources (e.g., time, energy, commitment) between professional and non-professional roles [

55,

56], the second on the quality of relationships and mutual expectations between role partners [

57], and the third on the subjective assessment of balance and the ability to shape its conditions [

58]. At the same time, multi-aspect approaches are emerging, which broaden the understanding of “life” beyond the family, pointing, among other things, to the importance of health, social relations, education, and civic participation [

59,

60]. However, these aspects were not identified in relation to the spatial specificities of residential and work areas (i.e., they do not take into account the distinct economic and social conditions prevailing in urban and rural areas). Working conditions in rural areas are perceived as less satisfying, also due to limited opportunities for development, lower incomes, and poorer infrastructure for recreation [

61]. By situating our analysis within this theoretical mosaic, we both identify WLB aspects and also interpret them in relation to resource allocation and boundary management, which is particularly pertinent in rural contexts where socio-economic constraints amplify the tension between roles.

This study uses a systemic approach that also has a multi-domain perspective, pointing to various factors that go beyond those typically considered in the area of work or life outside work. An added value is the focus of the study on rural areas, which, on the one hand, play a key role in the contemporary sustainable approach to economic development and, on the other hand, are marginalized in studies on the condition of human capital in these areas. The focus on rural regions therefore allows us to test how established theories translate into settings characterized by limited institutional support and distinct cultural norms, thereby extending the external validity of WLB research.

The PCA analysis identified three key aspects of WLB support for rural workers: leave (special and family leave), work (flexibility and access to WLB support), and work hygiene (regeneration at work and health). Interpreting these components through the lens of conservation of resources theory suggests that rural employees must prioritize between replenishing their physical and psychological resources and utilizing leave entitlements. When resources are scarce, taking leave may come at the expense of opportunities for on-the-job recovery. These aspects are confirmed by the results obtained so far [

53,

54], while broadening the perspective with important elements related to regeneration and the availability of emergency and family leave. Variables determining work hygiene indicate that the possibility of regeneration during work and access to comprehensive health care, including psychological support, play a particularly important role in creating conditions for work–life balance in rural areas. This is confirmed by studies on medical workers in rural areas and women farmers. In the case of nurses, the lack of rest and insufficient psychological support lead to overload, reduced job satisfaction, and deterioration of health [

5]. In turn, women working in agriculture point to insufficient systemic support, which results in them returning to work too early after giving birth and a deterioration in their physical and mental health [

6]. In addition, as confirmed by Istenič [

6], access to psychological support in rural areas is often limited due to a lack of anonymity, inadequate infrastructure, and low social acceptance of seeking help outside the family circle, which exacerbates feelings of isolation and hinders the achievement of work–life balance. This aligns with evidence that rural employees often rely on informal social networks for psychological health and may avoid formal health promotion programs because of stigma [

20]. Therefore, strengthening workplace-based regeneration strategies and destigmatizing mental health support becomes a practical imperative. Our findings thus bridge micro-level resource theories with macro-level discussions on rural health infrastructure, highlighting the need for integrated policies that combine leave entitlements with accessible psychological and health support.

The PCA results also verify the research hypotheses. In the context of conclusions concerning work hygiene, it is important to confirm both H1 and H3. Hypothesis H1 posited that using leave solutions would be negatively correlated with the use of work hygiene/regeneration measures; our analysis found a clear negative correlation (r = −0.509). People taking special leave and family leave are less likely to take advantage of health promotion activities. From a boundary-theory perspective, this trade-off indicates that employees may perceive formal leave and informal regeneration measures as substitutes rather than complements [

57]. Practically, this underscores the need for holistic WLB programs that integrate leave policies with health promotion and regeneration support, rather than offering piecemeal solutions; such integration could help rural employees to maintain their resources without having to choose between rest and professional obligations. This result is consistent with studies that highlight the lack of comprehensive WLB support offered by companies. For example, Sánchez-Hernández et al., showed that even among the most reputable employers, WLB solutions are implemented selectively—76% of companies offered extended leave, but only about 30% provided other facilities such as support for childcare or dependent persons [

62]. Similar conclusions can be drawn from a study by Puchalski and Korzeniowska, in which more than half of the companies offered health benefits, but these were sporadic and lacked a well-thought-out strategy [

63]. Poor access to regeneration opportunities during work is particularly important in rural areas, where comprehensive support systems are virtually non-existent. Employees are often limited to the limited public healthcare services available or have to resort to expensive private healthcare [

64]. The confirmation of H1 also supports the validity of implementing vacation solutions that go beyond the recreational nature of vacation. Our study took into account the leave solutions introduced in Poland (but also throughout the EU) by the so-called Work–life Balance Directive (Directive (EU) 2019/1158) [

65]. Its aim was to adapt the WLB support system in Europe to changing socio-economic conditions [

16]. Changes such as greater equality in childcare, the introduction of leave to care for other dependents, and the spread of flexible working arrangements make it much easier to balance personal and professional life. These forms of leave largely determined the length of the leave, thus confirming the validity of the reforms, also in the context of people working in rural areas. The positive assessment of the EU Work–Life Balance Directive in our findings suggests that regulatory frameworks can shift organizational practices and empower employees, yet without accompanying investments in workplace health and regeneration these reforms risk creating partial solutions.

The positive verification of hypothesis H3 (support for WLB among employees through work organization and working time is negatively correlated with support for occupational health) indicates that flexible forms of work organization, although considered one of the flagship solutions for supporting WLB, may reduce employees’ tendency to seek additional regenerative or health-related support. This finding points to a potential substitution effect, where greater autonomy in working time and location partly replaces other strategies of maintaining work hygiene. In line with boundary theory, flexible arrangements can blur the demarcation between professional and private spheres; without intentional recovery practices, employees may experience resource depletion and heightened work–family conflict, which our results confirm. This may also suggest that employers offering flexible solutions believe that this is sufficient to create a work–life balance culture, which is confirmed, among others, by the research of Peplińska and Zenfler, [

66]. Meanwhile, existing studies suggest that ensuring employee regeneration significantly contributes to improving their professional effectiveness and personal quality of life [

24,

35]. This is even more important in a flexible work environment, where the blurring of boundaries between work and personal life leads to overload, stress, and ultimately burnout [

67,

68]. However, in the analyzed group of employees from rural areas, the benefits of regenerative measures (e.g., relaxation areas, psychological support) are clearly marginalized. This may be due to limited availability of these services, cultural barriers to their perception, or lack of awareness of their importance [

64]. Hence, practical recommendations should target both organizational awareness—encouraging employers to pair flexibility with structured recovery opportunities—and community-level interventions that destigmatize the use of psychological and health services in rural settings. This requires further detailed qualitative studies.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that flexible work arrangements would substitute for special and family leave. Contrary to this expectation, we found a positive correlation between flexible work arrangements and the use of special and family leave, indicating that employees treat these solutions complementarily rather than substitutively. It should be emphasized that in Poland this type of leave is a right under the Labor Code and does not depend on the employer’s discretion. On the other hand, flexible working arrangements are offered on a more discretionary basis, depending on the employer’s decision and organizational culture, except for parents of children under the age of 8, who will have a statutory right to request such arrangements from 2023.

The lack of confirmation of hypothesis H2 is reflected in the results of other studies, which indicate that work flexibility not only does not limit the use of leave, but actually encourages its more conscious and fuller use, especially by fathers. Studies conducted in Germany by Wanger and Zapf [

69], and by Cha and Grady in the USA [

70], show that employees with access to flexible forms of employment are more likely to take parental and care leave, which indicates that they are more proactive in maintaining a work–life balance. The implementation of the WLB Directive in Poland has led to an increase in the use of both flexible working time by parents of young children and paternity and parental leave [

71]. According to European studies [

72], it is expected that the spread of flexible forms of work will further increase the willingness of employees to take care leave and leave on demand in order to reconcile work and private life [

71]. The results of the PCA analysis therefore confirm that, in conditions conducive to flexibility, employees do not treat WLB solutions as substitutes, but use them complementarily and proactively, even in rural areas. From a role accumulation and enrichment perspective, this complementarity illustrates how multiple resources and support mechanisms can mutually reinforce each other, enabling individuals to engage more fully in both caregiving and professional roles. This finding signals to policymakers and employers that flexible work should not be seen as a replacement for other forms of support but as part of an ecosystem of measures that collectively facilitate work–life integration.

The second objective of the analysis was to identify factors influencing the assessment of work–life balance and to typologize WLB experiences. Studies conducted in this area point to both endogenous determinants such as gender [

73,

74,

75] and age [

76] and exogenous determinants such as industry [

77], economic sector, availability of WLB support solutions [

56], and country of employment [

78,

79]. Despite the extensive research literature on the determinants of WLB, this topic has not been sufficiently explored in relation to rural workers. The vast majority of existing studies in this area focus on analyzing gender as the main variable differentiating the level of WLB achieved. A significant part of these analyses concerns exclusively the situation of women working in rural areas [

6,

64,

80,

81,

82]. These studies justify focusing on the situation of women who are still strongly rooted in the traditional family model, which hinders the achievement of WLB. Women in rural areas experience what is known as a double burden (explained by the second shift theory), associated with paid work and all domestic and care responsibilities [

83].

In this part of the study, two hypotheses were put forward: H4: Mature (older) employees and women rate their WLB lower. Mature men maintain higher WLB than mature women. H5: As the well-being of employees (not farmers) deteriorates, the intention to change jobs increases. The analysis of the results partially confirms both hypotheses, although with some reservations resulting from the internal diversity of the groups. Our typology highlights that age interacts with gender to shape WLB, underscoring how life course stages mediate role expectations and resource demands.

The above results partially confirm hypothesis H4, especially with regard to the lower WLB rating among middle-aged women compared to men in the same age group. The observation that mature men maintain a higher WLB than mature women is clearly confirmed. Similar conclusions have been reached by other studies conducted in Europe. Middle-aged women face the demands of work, childcare, and other dependent family members, which leads to increased work–family conflict [

6,

64]. Studies indicate that in women of this age, work–family conflict particularly reduces life satisfaction, and this effect intensifies with the age of the women surveyed [

84]. However, the thesis that women and older people generally assess their WLB worse requires clarification—younger women in group 1 assess WLB positively, which suggests that age, rather than gender alone, may be the decisive factor. It is only when women have children and other loved ones who require care that significant WLB disorders occur [

85]. In the literature, this is explained by social role theory, which assumes that women and men are socialized to perform different roles in the family and society [

86]. In an aging society, there is also a phenomenon known as the “sandwich generation,” which refers to middle-aged people (mainly women) who are professionally active and still caring for their minor children and elderly parents [

87]. These findings support social role theory by showing that WLB is contingent on the number and intensity of roles individuals occupy; for middle-aged rural women, simultaneous responsibilities across paid work, childcare, and eldercare compound role strain, reinforcing the need for targeted policy interventions (e.g., accessible childcare and eldercare services in rural areas) to alleviate this “sandwich generation” burden.

The study clearly confirms H5, which assumes a relationship between deteriorating employee well-being and an increase in the intention to change jobs. This correlation is clearly visible in all four clusters. These results therefore confirm that well-being and the assessment of one’s WLB have a significant impact on job stability, influencing decisions to change jobs. The strong association between well-being and turnover intentions resonates with the conservation of resources theory, wherein sustained resource depletion triggers withdrawal and exit behaviors; conversely, employees who experience resource gains are more likely to remain committed to their organization. For employers, this means additional costs related to recruitment, absenteeism, and training [

88,

89]. These results correspond to previous research findings, which indicate that the link between well-being and intention to change jobs is particularly strong in the public sector, which also offers jobs in rural areas (health centers, schools, government offices). Cross-sectional studies of medical and social workers from various European countries have found that feelings of burnout (in particular depersonalization), low job satisfaction, and high levels of occupational stress are among the main factors significantly increasing the intention to leave employment [

90,

91,

92]. For organizational and regulatory practice, this means that employee well-being must be considered an integral part of job quality. Therefore, investments in employee well-being should be seen not only as individual-level benefits but as strategic human resource measures that reduce turnover costs and support regional labor markets, particularly in rural areas where recruitment and retention are challenging. Organizations that implement wellness programs, mental health support, and good working conditions report lower staff turnover and higher work efficiency. In the broader perspective, this means lower healthcare costs and a more active labor market policy [

93].

The study provided a comprehensive overview of the issue of work–life balance (WLB) in the context of employees living in rural areas in Poland. One direction for future analysis should be an in-depth study of WLB among farmers as a specific occupational group, both in terms of individual assessment of work–life balance and the support system for achieving it. Not all solutions resulting from the WLB Directive apply to persons conducting their own agricultural activity [

6]. In addition, it is worth noting structural changes in the labor market, including the growing importance of flexible forms of employment and remote working opportunities. In rural areas, due to their natural assets, more and more coworking spaces are being created, which can foster conditions conducive to work–life balance and retain skilled staff in non-urban areas [

94]. Furthermore, drawing on evidence that planning workplace health promotion should consider employees’ place of residence and not only the company location, we recommend that policymakers integrate WLB initiatives with broader rural development strategies, including transportation, digital connectivity, and healthcare access.

5. Conclusions

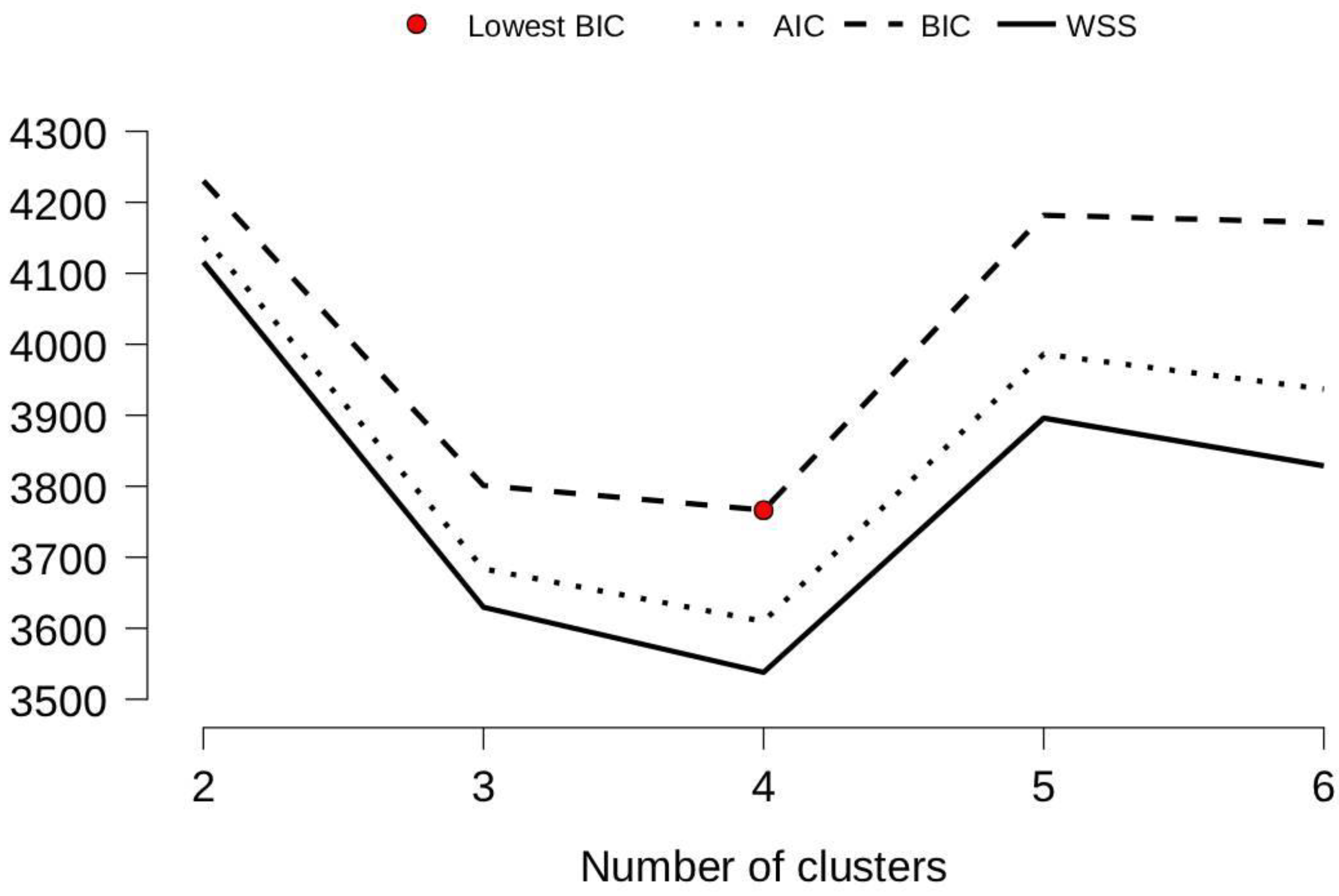

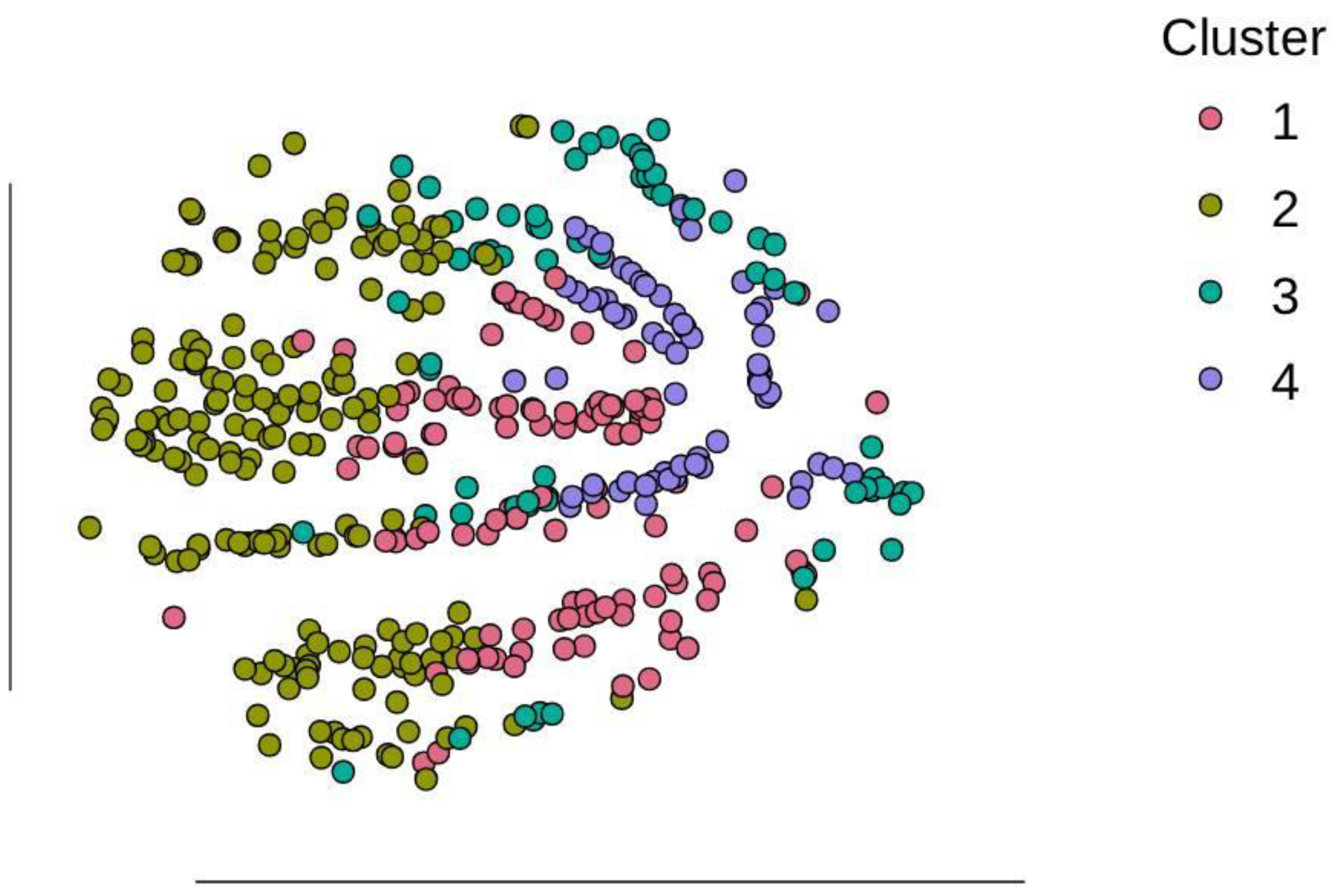

This study identified aspects of WLB support and types of employees based on their assessment of their WLB in terms of gender, age, sense of professional effectiveness, perceived stress, quality of personal life, and health status. Both research tasks were possible thanks to the use of PCA and the fuzzy c-means method. The following analyses were conducted on a sample (700 people), including farmers (PCA) and excluding farmers (571 people), with cluster analysis using the fuzzy c-means method (clustering).

The PCA results indicate three aspects and a division of WLB strategies among respondents—either temporary solutions (leave) or organizational solutions (flexibility) are used, while work hygiene measures (regenerative) are marginalized. This may result from a lack of knowledge about the available benefits, their low attractiveness, or cultural beliefs that work hygiene is not part of work but a solely private matter.

In the context of human resources policies, it is worth noting the need to integrate WLB solutions that take into account not only time and flexibility, but also the physical and mental well-being of employees. Workers in rural areas may particularly need support in making informed use of regenerative tools, which currently appear to be the least used. It is worth conducting further studies on the reasons for non-use—whether it is lack of availability or cultural taboo (e.g., rest = laziness). There is a clear need for comprehensive support for workers in rural areas in terms of work hygiene (regeneration) and health.

Based on these findings, we recommend that employers operating in rural areas develop holistic work–life balance strategies that combine flexible scheduling, promotion of statutory leave entitlements, and active regeneration measures. Employers should provide clear information and training on the availability of WLB benefits, invest in on-site or remote regeneration facilities (such as rest areas and telehealth psychological support), and actively destigmatize the use of mental health services. Tailoring WLB programs to the needs of women and caregivers—through accessible childcare and eldercare support and recognition of the “sandwich generation” burden—can help to retain experienced staff in rural labor markets.

Policymakers should extend WLB rights and support schemes to self-employed agricultural workers, ensure that mental health and general healthcare services are accessible in rural regions, and introduce incentives for employers to implement comprehensive WLB programs. In addition, WLB considerations should be integrated into broader rural development strategies by improving digital infrastructure, transportation links and the availability of coworking spaces, thereby facilitating flexible work arrangements and access to support services.

Empirical data analysis, conducted using the fuzzy c-means method, showed that clusters with higher work–life balance ratings differed in terms of demographic profile and organizational conditions.

An important conclusion drawn from the analysis of the data is the relationship between age and the assessment of the work–life balance of the respondents. Younger people, especially women classified in the first group, rated the balance between work and private life as moderately good. In contrast, the highest WLB scores were recorded among middle-aged men. This phenomenon may result from their greater professional and family stability associated with a reduction in the intensity of care responsibilities towards adolescent children.

Understanding how women and men perceive their own WLB can facilitate the identification of strategies and policies aimed at retaining women and men in the labor market, and professional organizations (industry associations, trade unions) can develop and implement HRD strategies and policies aimed at creating workplaces that are more supportive of the professional and personal goals of women and men.

This work may inspire further studies on supporting WLB among workers in rural areas (not necessarily farmers). The article provides new insights into patterns of work–life balance in rural contexts, allowing theoretical conclusions to be drawn and specific aspects and types of WLB for rural workers to be constructed. The results highlight the relevance and validity of the issues raised in theoretical, cognitive, methodological, and practical areas.

Overall, this study contributes to WLB scholarship by elucidating how distinct support aspects—leave, work flexibility, and work hygiene—interact in rural settings and by revealing age- and gender-mediated employee typologies through novel PCA and fuzzy c-means analysis. By situating these findings within a multi-theoretical framework and offering targeted recommendations, it advances theoretical understanding and provides actionable guidance for improving the well-being of rural workers.

The limitations of the study may result from the following, among other things: (1) Interpretation of correlations—does leave (other than vacation leave) actually improve work hygiene (regeneration), or is the opposite true? (2) Differences between professions—do leave and work hygiene mean the same thing for all professional groups? (3) The potential influence of hidden variables—are the results affected by factors such as stress, economic status, or work culture?