1. Introduction

Integrating sustainability into companies’ economic activities has been one of the main challenges faced by the private sector, with significant financial and socio-environmental implications [

1]. To address this issue, a group of financial institutions, in partnership with the United Nations (UN), released the report “Who Cares Wins”, aimed at guiding companies in integrating sustainability into their operations [

2,

3]. This document encourages the disclosure of corporate initiatives across the Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) dimensions, emphasizing the need for greater stakeholder participation in this process [

4,

5]. ESG has become a central pillar in the transformation of corporate responsibility, evolving from fragmented initiatives into strategic criteria for risk management and value creation [

2,

4,

5].

However, its consolidation as a guide for investors, managers, and regulators has been intensified with the creation of the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) and the establishment of guidelines like the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) [

6,

7]. The logic behind ESG suggests that companies performing well across these dimensions are more resilient, access lower-cost capital, retain talent more effectively, mitigate legal and reputational risks, and adapt better to social and environmental pressures [

7]. Nevertheless, the practical incorporation of ESG into corporate activities varies considerably by region, sector, and business model, often resulting in disconnected actions and research that, while extensive, remains fragmented [

8].

The ESG principles propose a balanced approach that fosters economic development, mitigates negative environmental impacts, and promotes social well-being while enhancing corporate transparency and ethics [

9,

10]. ESG encourages the development of initiatives ranging from process improvements for carbon emission reduction to the adoption of circular economy principles, and investing in renewable energy and green innovation [

11,

12,

13]. These initiatives also prioritize workers’ well-being, quality of life enhancement, and the promotion of diversity and anti-corruption practices [

6,

14]. In doing so, companies strengthen their corporate image, increase market value, and generate positive financial outcomes, positioning ESG as a key element in Corporate Sustainability (CS) [

6]. CS may be understood as the ability of organizations to create long-term value by integrating environmental, social, and economic dimensions into their strategy, culture, and operations [

15]. However, it extends beyond negative impact mitigation and involves generating positive externalities and adopting an active role in promoting sustainable development. This, in turn, consists of creating long-term value by ensuring the enduring viability of natural and human resources for the benefit of future generations [

3,

16,

17].

Within this context, ESG is increasingly understood as an instrument that enables CS, serving internally as a governance mechanism and externally as a means of accountability [

18,

19]. However, translating ESG into effective sustainability requires more than disclosure or high ESG scores; it involves strategic coherence, stakeholder engagement, and authenticity in corporate actions [

20,

21,

22]. ESG should function as a genuine lever for sustainability transformation and development. Yet, its concepts are often misused as a misleading or superficial response to institutional pressures, a phenomenon commonly referred to as greenwashing [

8,

23]. Indeed, there is a lack of reliable metrics and strategies capable of assessing the depth of ESG initiatives. While the need to distinguish “cosmetic” practices, those offering a limited portrayal of reality to meet investor expectations, yet generating little real impact, from genuinely transformative approaches with the capacity to produce significant socio-environmental outcomes is widely acknowledged, such a distinction is rarely operationalized in practice [

9,

22,

24]. This ambivalence reinforces the need for deeper qualitative analyses of ESG practices and their actual alignment with sustainable outcomes, as undertaken in this work. Therefore, the research gap that this work intends to help fill consists of identifying ESG’s fragilities to consolidate its knowledge, and to move it forward theoretically and practically, providing it more reliability, and contributing to the advancement of initiatives that effectively deliver sustainability [

8,

21,

25].

Despite the growing presence of ESG in the academic literature, numerous hurdles remain, revealing that some topics essential to its effectiveness continue to be addressed tangentially or uncritically from both theoretical and practical perspectives. The most striking hurdle is greenwashing, frequently mentioned as a recurring concern but without proposing how companies might prevent and avoid it [

26,

27,

28]. Another critical hurdle lies in the analysis of ESG practices themselves. Despite being a central theme, discussions on their effectiveness are often suppressed or reduced to financial and reputational outcomes, neglecting the materiality of their social and environmental impacts [

12,

29]. There is also a hurdle in examining the contradictions and limitations of ESG initiatives, as there is a tendency to treat them solely as a competitive advantage factor or risk management tool, overlooking the barriers to their adoption and maintenance within companies [

19,

30,

31]. Another underexplored hurdle concerns the integration of ESG’s three pillars into a systemic approach. Several studies recognize this need, but they often concentrate on one or two dimensions, most frequently governance, while issues from the social and environmental dimensions appear with less intensity [

17,

25,

29]. Additionally, there is a hurdle in standardizing ESG indicators that makes it difficult to measure and facilitate cross-sector comparisons, underscoring the need for innovative methodological approaches to address this limitation [

6,

32,

33]. A review of the scientific literature reveals a recurring effort to map ESG initiatives but without going into depth about how they can be carried out and help companies increase their sustainability, raising concerns about the depth of these analyses [

34,

35]. Almost twenty years after the first mention of ESG, considering the maturity it has acquired in the last decade and the launch of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the 2030 Agenda, it was hoped that the decoupling between economic activity, which is essential to keep the mankind demands, and positive socio-environmental impacts would have already narrowed dramatically, but this is not the reality [

15,

22,

36]. The high rates of pollution, recurring scandals involving abusive labor practices, and corruption in various economic sectors and governments reveal that considerable progress is still needed in the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda [

1,

7].

The identification of these hurdles faced by organizations allowed for an assessment of ESG’s real potential as a driver of organizational transformation by mapping which topics have been underexplored or neglected. These findings formed the basis for developing the research question that guides this work: How can ESG evolve to support better sustainability outcomes? To address this question, this work aims to develop a framework containing recommendations to overcome these hurdles and enable more effective ESG practices targeted for its key players (companies, rating agencies, regulatory bodies, academia, and other stakeholders). To this end, a systematic literature review (SLR) was adopted as the research method to provide an organized and in-depth overview of the current state of the art in ESG literature and its main gaps.

The motivation for identifying such hurdles and structuring a framework to overcome them stems from the recognition that ESG, while increasingly adopted as a guiding framework for corporate sustainability, still suffers from inconsistencies that undermine its credibility and transformative potential. Mapping these hurdles that have hindered ESG progress has made it possible to move beyond a debate on fragmented knowledge, which was previously spread across prior works, and is now synthesized within this work. This advances the state of the art in the ESG field, supporting further and deeper reflections, especially in relation to the persistent decoupling between expected and achieved results in sustainability. Additionally, in practical terms, this work proposes a framework with solutions to these hurdles, addressing them directly to their respective players, who can actually generate sustainable results, such as more coherent and materiality-oriented, thereby enhancing the ESG initiatives as effective instruments for sustainable development.

This article is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the method adopted, with emphasis on the procedures of the systematic literature review.

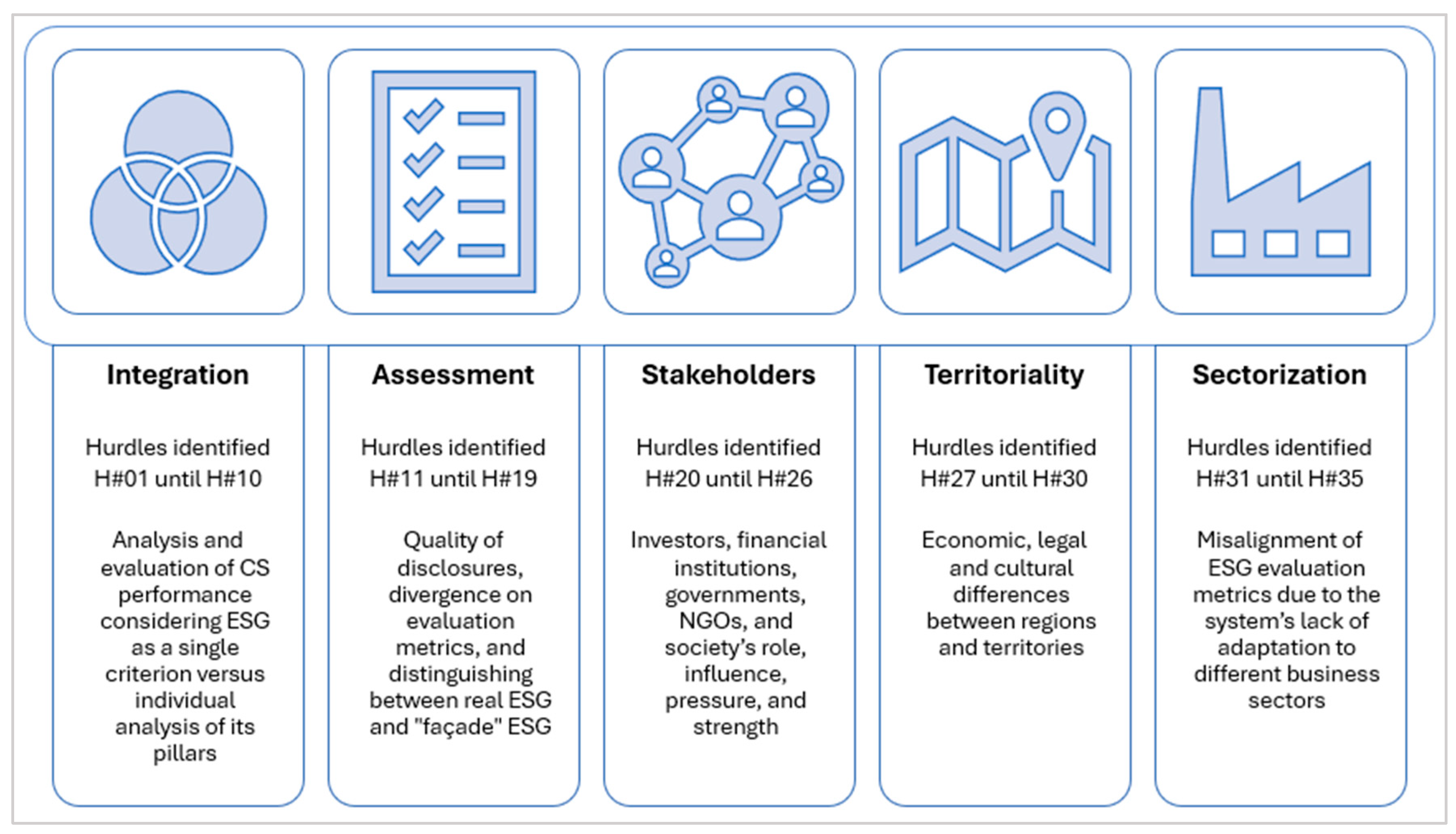

Section 3 presents the results, organized into five axes that group the main hurdles to the consolidation of ESG: integration, assessment, stakeholders, territoriality, and sectorization.

Section 4 proposes a framework with recommendations addressed to companies, rating agencies, guideline developers, governments, investors, civil society, and academia. Finally,

Section 5 presents the conclusion that synthesizes the theoretical and practical contributions of this study and outlines directions for advancing the ESG agenda.

2. Scientific Method

This work adopted the scientific method of a systematic literature review (SLR) with a qualitative interpretative approach, as this was considered the most appropriate strategy to critically assess academic research on ESG and its contribution to CS. An SLR is a non-biased method for evaluating and interpreting relevant research on a specific topic by following a clear, replicable, and systematic process. Its stages include (i) planning: justification of the topic’s relevance, identification of gaps or inconsistencies, and definition of the research question, objectives, and scope of the review; (ii) execution: selection of databases, keywords, inclusion and exclusion criteria, use of traceability protocols (in this case, PRISMA), data extraction, and synthesis; and (iii) dissemination and application: presentation of results, practical and theoretical implications, and recommendations for future research [

37].

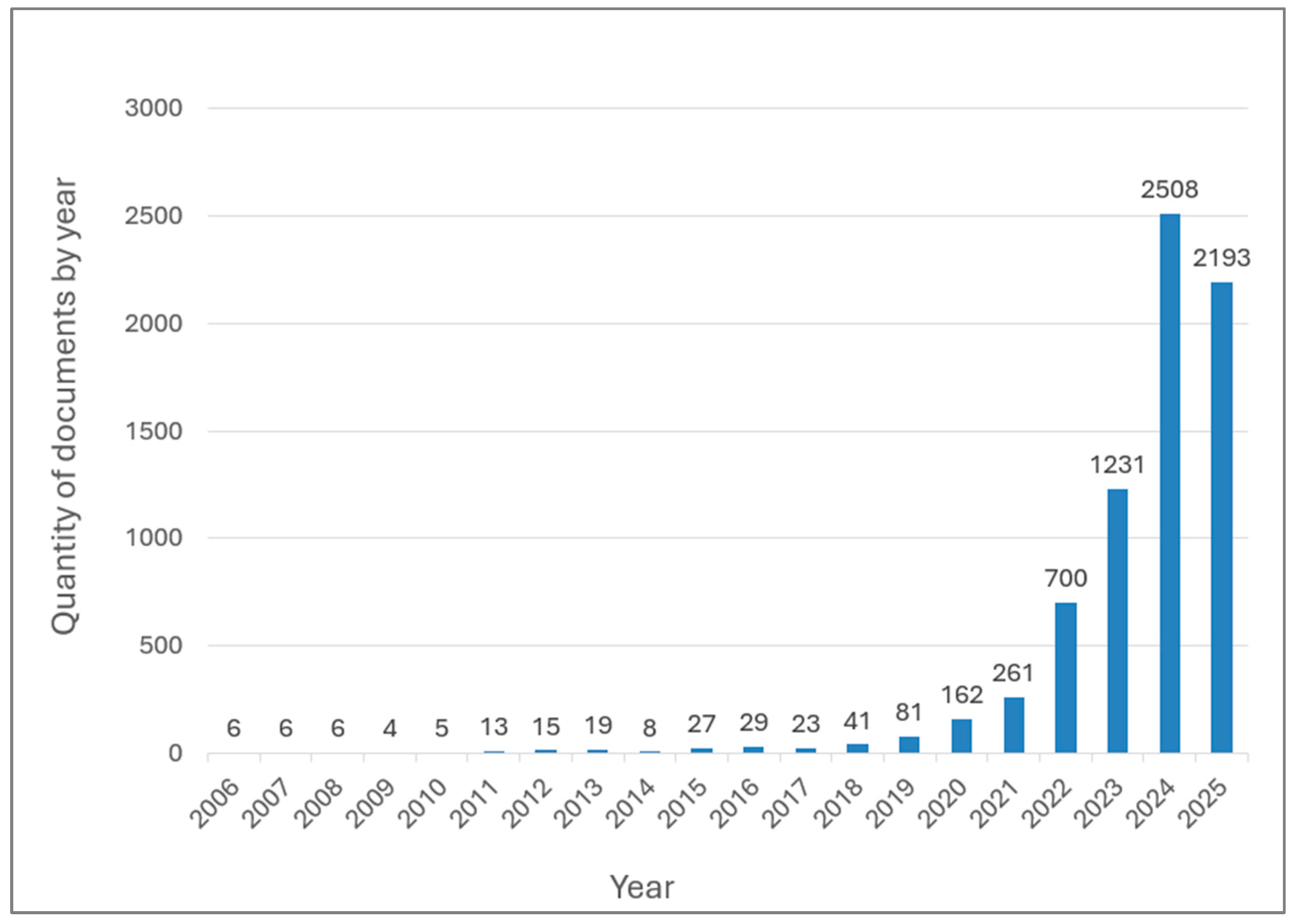

Given the exponential growth of the academic field on ESG since the launch of the PRI in 2006, as illustrated by the evolution of publications indexed in Scopus (

Figure 1), this topic was considered mature enough to support an in-depth SLR, as proposed in this work.

This growth has been accompanied by significant advances, such as the identification of positive relationships between ESG performance, financial performance, and risk mitigation [

11,

39]; greater access to capital for investment in expansion, technology, and innovation [

40]; and contributions to organizational legitimacy by promoting transparency and strengthening stakeholder relations [

41].

The choice of a qualitative interpretative approach stems from evidence observed within the analyzed studies. Despite the numerous scientific articles on ESG, the field remains dominated by quantitative models, primarily focused on financial returns, risk, and disclosure [

12,

42,

43]. As a result, certain ESG dimensions are only superficially explored, such as greenwashing and cosmetic ESG [

22,

41,

44], inconsistencies in ESG assessments [

30], reputational perception [

45], ESG reporting effectiveness [

46], and financial constraints [

44]. Furthermore, the literature reveals that ESG is a field marked by significant theoretical and methodological fragmentation, limiting the applicability of traditional quantitative meta-analyses. For instance, while some studies examine ESG as an integrated construct across the three pillars [

25,

47,

48], others analyze each pillar individually [

24,

34,

49], and a few address sectoral or contextual specificities [

46,

50,

51]. This scenario highlights the complexity of the field and underscores the need for a systematic review that, by emphasizing thematic categorization and critical interpretation, can provide greater conceptual clarity and guide future research.

Another relevant reason for the methodological choice was the need to identify patterns of convergence and contradiction across theoretical strands. For example, the corporate governance pillar is widely recognized as the most consistent ESG factor [

12,

43,

48], while findings related to the environmental pillar remain ambiguous [

26,

46,

47], and the social pillar remains underexplored. These factors require an approach capable of comparing meanings, not just measurements [

21]. It is also worth noting that, although specialized software is widely used in systematic reviews, this work has opted for manual analysis to ensure a deeper and interpretative reading of the selected articles. This decision enabled the identification of conceptual nuances, implicit arguments, and contextual specificities that could be overlooked by automated tools. While review support software may be efficient in identifying patterns, term frequencies, and co-occurrence networks, it cannot replace the researcher’s analytical capacity to uncover more subtle dimensions, such as theoretical contradictions, interpretative gaps, or non-standard methodological approaches, as occurred with [

21].

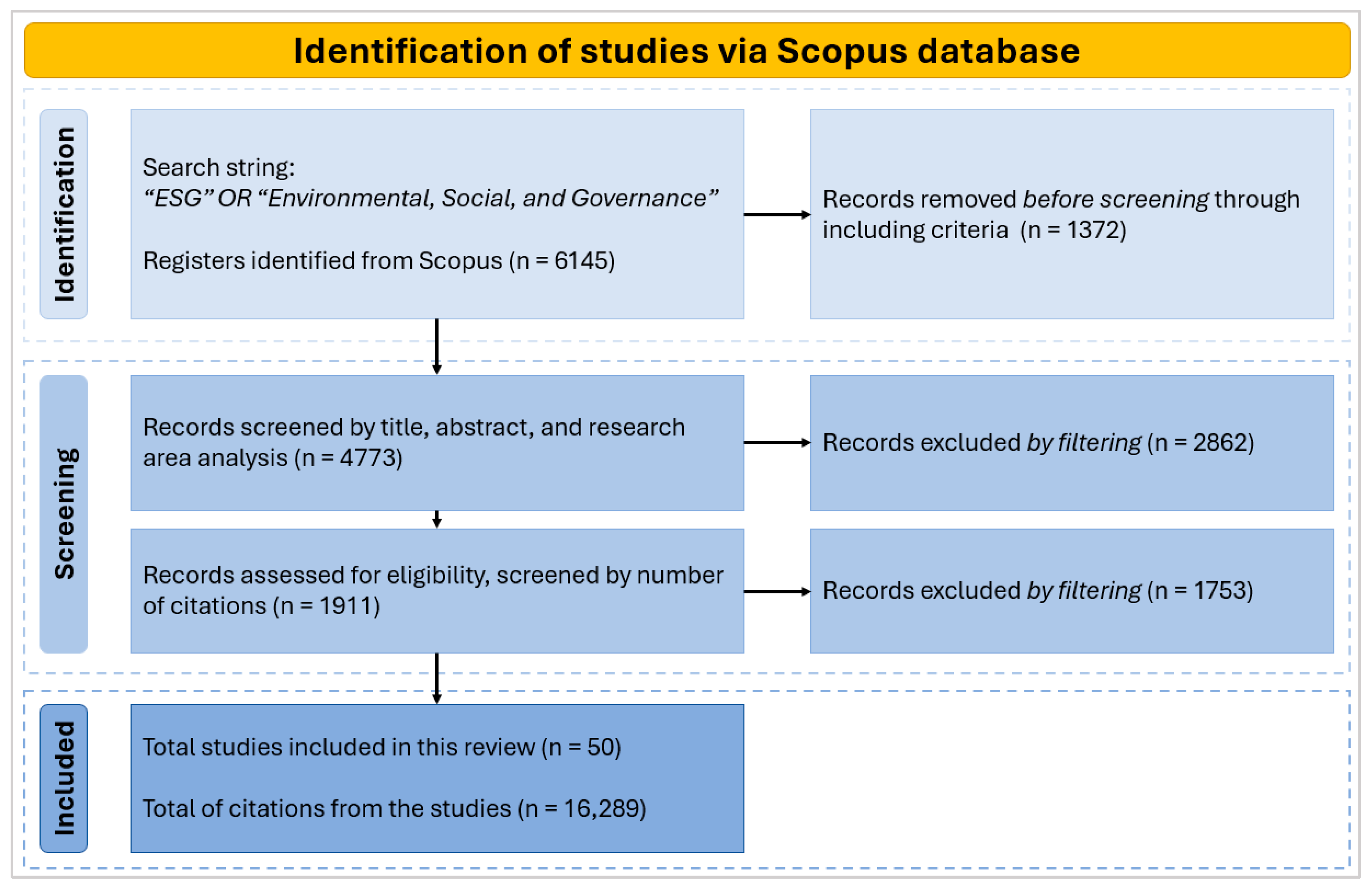

Finally, this SLR was planned and conducted following the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology, adapted for qualitative studies [

52]. This technique enables a rigorous synthesis of the state of knowledge, providing a useful foundation to inform future research agendas, support corporate policies, and guide institutional decisions on ESG and corporate sustainability [

53], as outlined in

Figure 2.

To conduct this work, address its research question, and achieve its objective, the Scopus database was defined as the source of scientific production on ESG due to its scholarly credibility, strict journal inclusion criteria, and the substantial volume of results on the topic [

27,

55]. The search was restricted to terms appearing exclusively in the “Article Title” field. The initial sample was defined using systematic strategies and inclusion/exclusion criteria. From the 6145 records retrieved in Scopus, 1372 were removed before screening, based on the following inclusion criteria: publication year (from January 2020 to March 2025, corresponding to the five most recent years relative to the search date, 26 March 2025), document type (peer-reviewed articles or reviews only), and language (English only, as it is the most widely used language in the scientific community). Subsequently, titles and abstracts of the remaining 4773 records were reviewed to confirm thematic relevance, excluding those unrelated to the subject, such as those from the fields of health, medicine, and chemistry, resulting in 1119 eligible documents. Next, only articles with more than 100 citations were selected, indicating they are among the most influential in the academic literature, narrowing the sample to 158 documents (1753 excluded). Finally, the corpus was delimited to 50 documents (see

Supplementary Materials). This number reflects the concentration of influence within the field and the feasibility of conducting an in-depth qualitative analysis. The 50 selected articles account for 61.4% of the total citations of the previously identified influential works, ensuring that the sample represents the most authoritative voices in the ESG debate. Moreover, the citation threshold of the first (over 1150 citations) and the fiftieth (182 citations) demonstrates that the chosen set captures a consistent level of scholarly recognition and impact. The decision to focus on 50 articles also follows methodological precedents in systematic reviews, which emphasize the importance of balancing breadth and analytical depth to enable a rigorous examination of conceptual and methodological gaps [

21,

56,

57]. This delimitation ensured this work’s operational feasibility, particularly given the deliberate choice not to employ software-assisted tools, as previously mentioned.

An in-depth reading of the selected articles enabled the identification of several hurdles frequently highlighted as relevant but still lacking clarity or analytical depth. Between two and six hurdles were extracted from each article, which were then systematically organized and grouped by affinity.

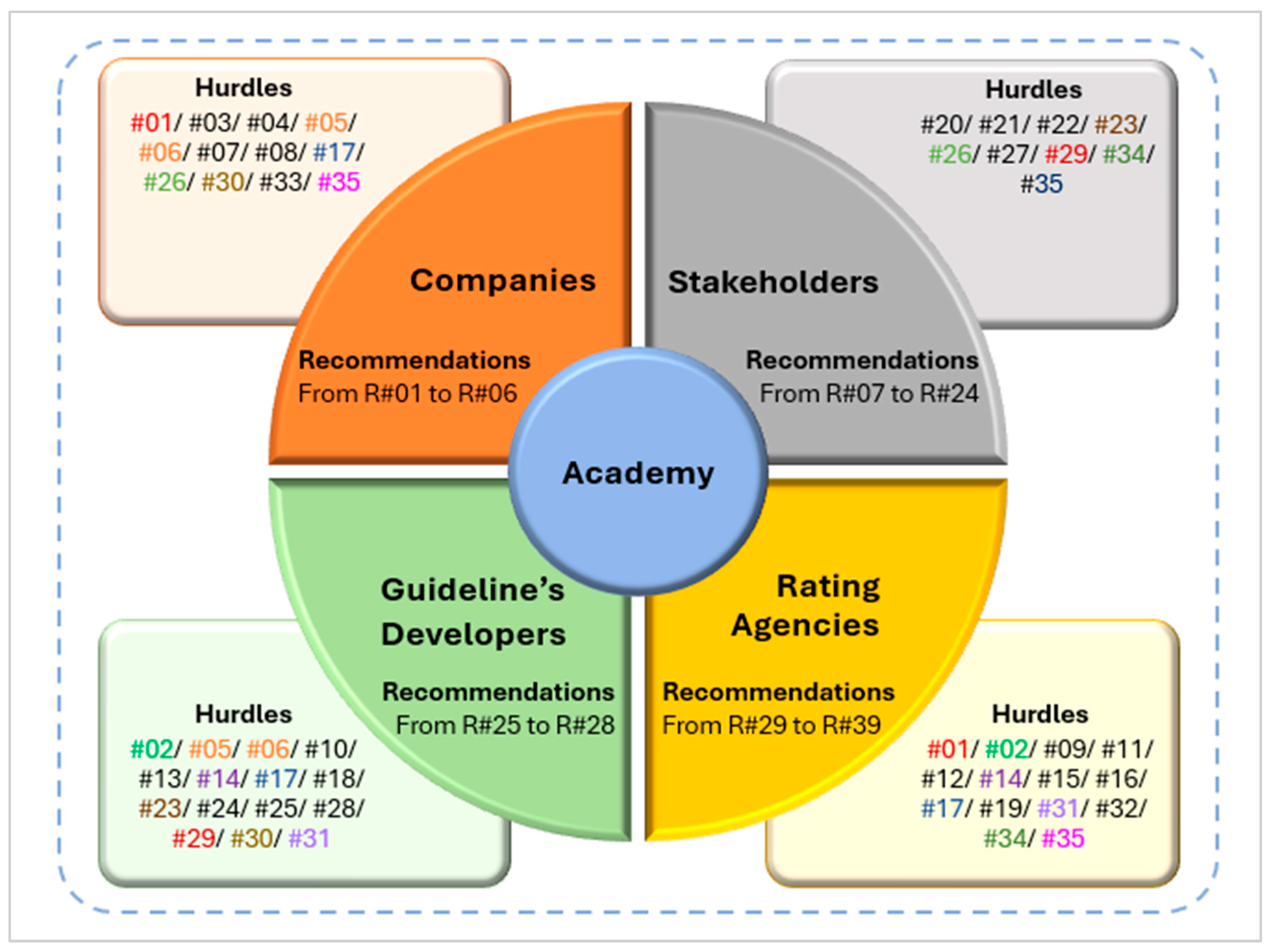

4. Recommendations to ESG Forward

The 35 hurdles previously identified in this work were analyzed as opportunities for ESG forwardness. This approach generated new perspectives on persistent challenges, enabling the development of a framework with recommendations addressed to companies, stakeholders, ESG rating agencies, guideline developers, and the academic community (i.e., future research). In this section, the framework’s recommendations are labeled as “R#” followed by their corresponding sequential number; the full table can be found in

S3. In this analysis, each topic may be relevant to more than one player. Therefore, some actions require collaborative solution-building among them (see

S4). Additionally, academia plays a transversal role that intersects with all other players, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

As shown in

Figure 4, the Hurdles highlighted in color are those addressed for more than one player. Accordingly, this framework was structured to align the specific responsibilities of each player and promote greater coherence between evaluation, disclosure, regulation, stakeholder engagement, and scientific research, to support more effective organizational practices in sustainability.

4.1. Companies

Although companies lie at the core of scientific research on ESG, since they are the primary agents responsible for generating or mitigating environmental, social, and governance impacts, their role in pursuing sustainability, while already well defined, is still marked by uncertainties [

9,

43,

68]. On the one hand, it is well established that achieving sustainability requires companies to align their processes, policies, and practices with this goal [

42]. On the other hand, uncertainty persists about how to move forward, driven by the multiplicity of guidelines to follow, evaluation metrics to meet, and the fragmented demands of numerous stakeholders [

19,

48,

59].

One recommendation that may be transformative for companies is to deepen their corporate culture around ESG principles (R#01). This begins with mapping internal processes and clearly identifying, at all organizational levels, which processes relate to financial performance (such as cost reduction or productivity gains) and which relate to sustainable performance, since, although closely interconnected, these goals are fundamentally distinct [

14,

60]. Companies need to establish well-defined policies to clarify how they manage their decision-making criteria based on the ESG pillars (R#02). When rigorously implemented, these two recommendations naturally foster greater employee engagement with the organization’s sustainability commitments [

40,

75]. This, in turn, contributes to more effective operational management, stronger ESG initiatives, higher-quality ESG reporting, and a reduced risk of greenwashing [

7,

23].

It is also recommended that companies adopt disaggregated metrics for the E, S, and G pillars to more accurately reflect the specific characteristics of their initiatives (R#03), thus enabling a clearer understanding of positive and negative impacts. This initiative facilitates analysis of synergies and trade-offs among the pillars while also strengthening transparency for stakeholders. Additionally, companies must make progress in clarifying the indicators disclosed (R#04), moving beyond “window dressing” approaches and pointing out the materiality of each practice.

Governance strategies, in this context, should be designed to incorporate their moderating function in environmental and social decisions, allowing this pillar to act as a coordinating mechanism (R#05) that balances ESG initiatives and financial performance. It is also recommended that companies take an active stance in response to the diversity of regulatory and sectoral requirements, promoting adaptations that are consistent with their territorial and industrial context (R#06).

4.2. Stakeholders

Stakeholders bear the difficult task of demanding better results from companies, clearer and stricter policies and regulations from governments, and more accurate and transparent information from rating agencies (R#07). This responsibility should not fall solely on investors, but rather be shared by all those directly or indirectly affected by economic activity.

Institutional investors, given their greater capacity to mobilize capital, should exert qualified pressure on companies to promote more comprehensive reporting, including impact indicators and thematic disaggregation (R#08). It is recommended that they adopt their own ESG assessment criteria, complementing agency ratings with internal analyses based on long-term goals (R#09). They can also influence the evolution of ESG practices by demanding empirical evidence of the correlation between sustainable actions and economic value (R#10) through active engagement in shareholder meetings, critical review of disclosure guidelines, and portfolio selection based on their materiality criteria.

On the other hand, individual investors, who are often unfamiliar with the complexity of ESG metrics, should seek greater informational literacy, learning to distinguish between cosmetic and effective reporting (R#11). For this to occur, investment platforms and financial products must offer accessible and comparable information about the integrity of sustainability practices, avoiding misleading signals from generic ratings. Additionally, investor protection agencies should regulate the language used in ESG-labeled products. Equipped with this knowledge, individual investors can demand greater transparency from rating agencies and assess whether their evaluation criteria genuinely align with their interests (R#12). Since their voting power in corporate decisions reflects their actual motivations, this group of stakeholders can strengthen the link between market dynamics and sustainability, translating ESG into tangible financial decisions (R#13). They are also in a position to demand clearer corporate ESG disclosures (R#14), ensuring transparency regarding where their investments are truly generating sustainable development.

Governments and regulatory bodies, as key stakeholders, have a broader influence over the impact generated by corporate economic activity given their role in designing relevant policies to guide and supervise this activity. Policymakers at the national, regional, and municipal levels must work collaboratively to enact laws and regulations that encourage companies to pursue sustainability (R#15). They can also foster local development indicators tied to corporate initiatives (R#16). Governments and regulators should establish institutional frameworks that incentivize sound ESG practices while penalizing opportunistic misbehavior (R#17). In this regard, strengthening regulations on disclosure quality is recommended, with minimum requirements for materiality, impact, and third-party verification (R#18). Laws and regulations should also recognize the sectoral and territorial diversity of companies, tailoring regulatory requirements to companies’ size, context, and operational structure (R#19). Moreover, it is the regulators’ role to ensure that rating agencies operate with auditable criteria and are free from conflicts of interest (R#20), especially in contexts where their ratings influence credit decisions, investments, and access to capital.

Civil society also plays an important role in this ecosystem. Once corporate sustainability reports are published, they are accessible to all, enabling the public to support initiatives that contribute to sustainable development and question those that may harm the environment or social well-being in affected communities (R#21). The media play a key dual role: disseminating information to the public and amplifying its voice, helping to clarify company disclosures and their actual impacts, whether positive or negative (R#22). These stakeholders, including NGOs and consumers, should expand their roles as surveillance agents by exposing cases of greenwashing, pressuring companies for more effective practices, and promoting accessible ESG knowledge (R#23). They can also serve as external validators of disclosed data and as legitimate channels for representing diverse interests (R#24), which are often overlooked in conventional metrics. Encouraging public participation in advisory councils, governance forums, and sectoral committees can help increase the legitimacy of the ESG practices adopted.

4.3. ESG Rating Agencies

Although, from certain perspectives, ESG rating agencies may also be considered stakeholders for companies, their role is more closely tied to the functioning of financial markets than to the companies being assessed. For this reason, in this study, they are treated as a separate group. The weaknesses identified in the literature regarding these agencies point to empirical hurdles; that is, some issues remain underexplored, not because of a lack of interest, but because the corresponding practices are still underdeveloped or not sufficiently mature in real-world applications. Examples include the need for the development of objective metrics to (i) measure and evaluate “moral capital” and “organizational legitimacy” [

64]; (ii) clear metrics for evaluating ESG in different sectors, considering their specificities related to the impacts caused [

7,

27,

69]; and (iii) create more robust assessment systems for qualitative data, capable of over-ride binary proxies such as “does or does not,” by assigning different scores based on the depth of corporate commitment to each disclosed practice [

60,

66]. Another recurring hurdle is the divergence between ESG rating agencies, which is consistently highlighted as a challenge for the companies evaluated [

49,

50,

67]. These discrepancies generate additional work and costs for firms, as well as uncertain information for investors [

30,

76].

To mitigate these negative effects, agencies could establish a shared panel of definitions for the ESG pillars, balancing assessment criteria and reducing discrepancies in scoring between agencies (R#25). An additional measure would be greater transparency in disclosing their assessment methodologies (R#26), allowing companies to better understand how to develop their initiatives and enabling investors to more accurately interpret and align their resources. This would also help combat the growing distrust around the integrity and authenticity of ESG ratings and reduce the risk of misinterpretation, particularly about weighting schemes and the conversion of data into final scores [

50]. However, excessive standardization in the pursuit of methodological coherence across agencies must be critically reviewed whenever it compromises the contextual sensitivity of ratings.

Agencies should consider developing indicators capable of capturing specific dynamics among the ESG pillars and adopt classification approaches that incorporate auditable qualitative metrics, not relying solely on self-reported data (R#27). Furthermore, they should implement mechanisms to minimize the risk of greenwashing, such as cross-checks with external sources and independent verification protocols (R#28).

Advancing in this direction requires the development of more dynamic analytical models that incorporate instrumental variables and counterfactual testing, supported by tools capable of simulating scenarios and identifying causal relationships. These models should also account for the strategic trade-offs companies often make between financial objectives and ESG goals and promote sector-wide alignment on what should genuinely be considered material in sustainability assessments [

47,

69].

4.4. Guideline Developers

Given the multiplicity of approaches and the conceptual fragmentation observed in the academic literature on ESG, guideline developers (like GRI, SASB, and TCFD, among others) play a central role in building a shared vocabulary for companies, investors, regulators, and civil society [

61]. As previously discussed, the lack of standardization, the excessive simplification of disclosure models, and the insufficiency of auditable criteria generate informational asymmetries, incentivize cosmetic practices, and hinder comparability across organizations and sectors [

19]. In this context, guidelines cease to be merely technical instruments and instead function as institutional mechanisms that are essential to ensuring the credibility, transparency, and effectiveness of ESG [

69].

To fulfill this strategic role, it is recommended that guideline developers prioritize reducing interpretative ambiguity in the proposed criteria (R#29), ensuring that their parameters are robust enough to capture sectoral and territorial specificities while also remaining sufficiently clear and objective to enable global adoption. To achieve this, guidelines must evolve beyond binary models, which focus on the mere presence or absence of initiatives, and move toward standards that promote the measurement of the actual impact of reported actions (R#30), taking into account their materiality, scope, and depth. This evolution also requires the incorporation of auditable qualitative variables capable of capturing the degree of organizational commitment (R#31), overcoming superficial, self-reported metrics. Additionally, proposed disclosure models should include mechanisms to ensure transparency regarding the influence of stakeholders in decision-making processes and the content reported (R#32), enabling the identification of conflicts of interest and greenwashing practices.

Guidelines should also explicitly state the risks associated with the lack of materiality in disclosed actions (R#33), providing companies with clear direction on how to avoid merely formal initiatives. Finally, it is proposed that guideline developers promote collaborative processes with other ESG ecosystem players, including rating agencies, regulatory bodies, and academic institutions, to foster conceptual convergence and ensure that standards evolve in a manner that is responsive to social demands and advances in scientific research (R#34).

4.5. Academia (Future Research)

Academia plays a transversal role in advancing the ESG agenda, particularly through identifying research gaps, developing new metrics, and proposing more refined analytical models. The literature reviewed indicates that ESG assessment should begin with assigning differentiated weights to the pillars, reflecting their sectoral, regulatory, and territorial specificities, before reconstructing an integrated perspective that captures complementary or compensatory effects. Therefore, future studies can foster models that incorporate interaction terms, sensitivity tests, and metrics capable of distinguishing between cosmetic ESG practices and those that are genuinely transformative (R#35). This represents the next methodological step toward shifting from a simplistically aggregated ESG approach to a truly balanced integration. Such models should analyze the isolated impacts of each ESG pillar while accounting for variables that produce conflicting results (R#36), as in the studies by [

34,

46] mentioned earlier. Academia is also expected to advance studies focused on the balance among ESG pillars, fostering the development of metrics that capture trade-offs between them (R#37) and encouraging more research on the Environmental and Social pillars. Future studies could identify characteristics that define “moral capital” and organizational legitimacy (R#38) so they can be operationalized by rating agencies in the development of evaluation metrics. Moreover, research can explore how companies may overcome intraorganizational complexity regarding the effectiveness of ESG practices (R#39) to improve their performance.

There is also a lack of models that investigate the distributive effects of ESG practices on non-financial stakeholders or that examine the level of effective stakeholder participation in the development of integrated and sustainability reports. Without such methodological and conceptual refinements, stakeholder theory, though widely celebrated in discourse, risks remaining underutilized in its practical and empirical application.

5. Conclusions

This work began with the recognition that, despite the growing relevance of ESG in the academic literature and organizational practices, significant hurdles persist that challenge its effectiveness as a transformative instrument toward CS. Theoretical and methodological dispersion, informational asymmetries, superficial analyses, and the absence of robust metrics for qualitative data disclosed by firms undermine the consolidation of a coherent and comparable global model. Based on the analysis of the 50 most-influential articles, the main hurdles to ESG forwardness were mapped, thematically organized according to underexplored topics, and a framework with recommendations was proposed for different players within the ESG ecosystem.

This work addressed its research question by identifying 35 hurdles that have hindered ESG progress and, based on this analysis, proposing solutions to overcome them. From a methodological perspective, this systematic review exposes the gaps in evaluation metrics, disclosure practices, and stakeholder engagement, translating these findings into 39 actionable recommendations for key ESG players (companies, rating agencies, guideline developers, regulators, academia, and other stakeholders). In doing so, this article moves beyond the identification of challenges and offers concrete pathways to align ESG more closely with sustainability outcomes. Also, this work contributes to the refinement of ESG and the qualification of its practices, achieving its objective. The interpretive qualitative approach adopted, centered on the critical categorization of the hurdles identified and the formulation of targeted recommendations, enabled shedding light on neglected areas, promoted an integrated reading of this research field, and offered paths for both theoretical advancement and applied development of the ESG agenda, helping to bridge the research gap identified.

This work’s findings reveal that although ESG is widely recognized as a corporate tool to foster sustainability, it remains marked by asymmetries across its pillars; conceptual and practical hurdles that fail to account for the particularities of players, sectors, and territories; and, in many cases, cosmetic initiatives or greenwashing. These issues compromise coherence in evaluation processes and restrict ESG’s transformative potential. The recommendations proposed in this work provide integrative, materiality-oriented guidelines seeking to align ESG instruments with the real demands of sustainability and the SDGs. In this way, this work advances the construction of an applicable framework to strengthen the legitimacy, effectiveness, and practical usefulness of ESG as a sustainable development instrument.

From a theoretical standpoint, this work identifies the main hurdles that have limited the coherence, comparability, and authenticity of ESG initiatives, thereby synthesizing neglected or underpinned themes in prior works. However, its theoretical contribution lies beyond synthesizing previously dispersed knowledge; this work offers new conceptual contributions and directions in which the ESG foundations must advance. By integrating different perspectives, it broadens the theoretical basis for future research, deepens the academic debate in a field that is still being consolidated, helps to fill its research gap, and advances the state of the art in ESG. Regarding limitations, this research worked with articles from 2020 to 2025; further research could help keep its findings up-to-date, as this is an evolving topic.

From a practical perspective, the contributions of this work can help the ESG key players to overcome the hurdles that jeopardize the ESG progress towards sustainability. By following the proposed framework, companies can improve the effectiveness of their sustainable initiatives; agencies can refine their evaluation frameworks, improving the quality and transparency of their evaluation metrics; stakeholders can increase their involvement with knowledge about their role and influence; and this can strengthen institutional mechanisms.

These contributions are directly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals, particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), by promoting more transparent and accountable corporate practices; SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure), by encouraging innovation in ESG metrics and evaluation processes; and SDG 16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions), by advancing more reliable and legitimate institutional mechanisms. Accordingly, this study positions itself at the scientific frontier of the debate on ESG as a supporting tool for the sustainable transformation of global economic activity.