Abstract

Based on the concept of sustainable development, China has formulated a “dual carbon” strategic plan. Steel enterprises are in urgent need of a green and low-carbon transition, requiring substantial funding for technological upgrades and transformation. The “Reform Plan for the Legal Disclosure System of Environmental Information” implemented in 2021 explicitly mandates that high-pollution industries such as steel and cement must disclose their environmental information. Green finance policies impose numerous restrictions on steel enterprises, making it imperative to address the issues of difficult and expensive financing. Against this backdrop, this paper uses listed companies in China’s steel industry from 2014 to 2023 as a sample to empirically examine the impact of environmental information disclosure on debt financing. The study finds that environmental information disclosure is negatively correlated with corporate debt financing costs and positively correlated with the scale and structure of debt financing. Neither enterprise size nor nature can reduce debt financing costs. The publication of a standalone environmental report can enhance the impact of environmental information disclosure on debt financing costs. Further research reveals that the impact of environmental information disclosure on debt financing exhibits a dual time-node effect, with the time nodes corresponding to the year of the promulgation of the Environmental Protection Law and the year of the release of the Reform Plan for the Legal Disclosure System of Environmental Information. Finally, conclusions and policy recommendations are proposed.

1. Introduction

In response to increasingly severe environmental issues, countries around the world are engaging in environmental protection activities in ways that suit their own circumstances. To promote sustainable development, China has introduced a series of environmental protection policies and invested substantial funds. During the 13th Five-Year Plan period, annual environmental protection investment by the Ministry of Environmental Protection increased to approximately RMB 2 trillion, with total social investment in environmental protection exceeding RMB 17 trillion. During the 14th Five-Year Plan period, investment has continued to grow, with diversified funding channels such as central government budgetary investment and green finance significantly enhancing the participation of private capital. In 2023, income from the environmental services industry exceeded RMB 1.05 trillion, providing a solid financial foundation for the battle against pollution and the achievement of carbon peaking and carbon neutrality targets. As a major heavy industry country, China has consistently ranked first in global steel production, with crude steel output exceeding 9.6 billion tons over the past decade, accounting for more than 54% of the world’s total production during the same period. To address environmental issues, the Chinese steel industry must undergo reform. The extensive development model, which has caused significant damage to both resources and the environment, is no longer compatible with sustainable development. Steel enterprises need to upgrade their technologies, conduct R&D on environmentally friendly processes, adopt clean facilities, and implement environmental management measures [1]. It is estimated that achieving “carbon peaking” in China’s steel industry will require nearly RMB 3.5 trillion in investment, and from 2030 to 2060, transitioning from “carbon peaking” to “carbon neutrality” will require RMB 19 trillion in funding [2]. Facing pressures from environmental concerns, competition, excess production capacity, and industry downturns, issues related to debt financing have become increasingly prominent [3,4]. The implementation of the Environmental Protection Law in 2015, along with subsequent specialized environmental regulations, has further exacerbated the debt financing challenges faced by steel enterprises.

Heavily polluting steel enterprises exposed to high environmental risks are required to disclose information regarding the environmental obligations fulfilled during the current year. The Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China, revised and implemented in 2015, for the first time legally mandated enterprises to disclose environmental information. It requires key pollutant-discharging entities to truthfully disclose to the public their major pollutant emissions and control measures. Under the “dual carbon” strategy, this has further accelerated the environmental information disclosure process for heavily polluting steel enterprises. In 2021, the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council issued the Reform Plan for the Legal Disclosure System of Environmental Information, further establishing a systematic disclosure framework. The plan explicitly includes key pollutant-discharging entities, enterprises subject to mandatory cleaner production audits, listed companies and bond-issuing enterprises penalized for environmental violations as disclosure subjects. It requires the disclosure of 11 categories of key information, including pollutant emissions, carbon emissions, and ecological and environmental emergencies. By establishing a unified national mandatory environmental information disclosure system, centralized public access and dynamic updates of information have been achieved. As of 2023, more than 85,000 enterprises nationwide have been included in the disclosure list, representing an increase of over 50% compared to 2021. According to data filtered from the WIND database, 29 steel enterprises disclosed environmental information consistently over the ten-year period from 2014 to 2023. Driven by policy, the content of corporate disclosures has become increasingly detailed. Shougang Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China.) was even ordered to suspend production for rectification due to environmental protection issues, indicating that China’s environmental policies have a significant impact on the steel industry.

In order to expedite the implementation of the national “dual carbon” strategy and achieve China’s green, low-carbon and sustainable development, while also addressing the challenges of difficult and costly financing for real economy enterprises, China has introduced green credit and green finance policies. Under these policies, banks and other financial institutions review corporate environmental information, and enterprises that meet environmental protection requirements are eligible for specific loans, thereby alleviating their financing difficulties [5].

A review of domestic and international literature reveals that studies closely related to this research are limited. “Environmental information disclosure” is a uniquely Chinese environmental regulatory approach and is more applicable to the Chinese market. Li Guangzi, Zhang Xiaofeng et al. (2025) [6] treated the implementation of the Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China as a natural experiment and found that strengthened environmental constraints had a significant suppressive effect on the asset-liability ratio of heavily polluting enterprises. Specifically, the enhancement of environmental constraints affected corporate debt financing behavior in three main ways: by reducing the debt financing capacity of heavily polluting enterprises, lowering their target capital structure, and decreasing the supply of debt capital to such enterprises [6]. Huang Zhen, Chen Siman et al. (2025) [7], based on a quasi-natural experiment under the Environmental Protection Tax Law, found that the policy of replacing pollution discharge fees with environmental protection taxes primarily increased the debt financing costs of enterprises in regions with higher tax burdens through risk exposure and cost constraint mechanisms. However, the disclosure of high-quality environmental information by enterprises can mitigate the adverse impact of the tax reform policy on their debt financing costs [7]. Zou Yang and Sun Yuxin (2023), using panel data of A-share listed companies in China from 2012 to 2022, examined the impact of corporate ESG performance on debt financing costs and found that improvements in ESG performance help reduce such costs [8]. Guo Mingjie and Wang Jiaqian (2023) [9] found a negative correlation between ESG performance and financing costs among heavily polluting enterprises in China. The impact of ESG sub-dimensions on financing costs varies by region and ownership structure, and media supervision has a negative moderating effect [9]. Meng Xiangsong, Chen Lei et al. (2023) explored the impact of environmental information disclosure quality on financing constraints of Chinese enterprises, as well as the moderating effect of internal control on this relationship [10]. Hui An, Chenyang Ran et al. (2025) [11], using a sample of A-share listed companies in China from 2013 to 2020 and based on linear regression analysis, found that ESG information disclosure scores are significantly positively correlated with firm value. ESG information disclosure enhances firm value by alleviating financing constraints [11]. Zhou Yingying, Shi Zilin et al. (2022), based on a data sample of 182 listed companies in the energy sector on China’s A-share market from 2012 to 2019, found that environmental information disclosure has a significant positive impact on corporate financing efficiency, with corporate social responsibility serving as a mediating variable in this relationship [12]. Yin Shihao, Lin Zhongguo et al. (2025) [13], using a sample of 664 listed companies that disclosed environmental information from 2009 to 2021, employed a difference-in-differences model. The empirical results indicate that mandatory government environmental credit ratings can help lending institutions better understand corporate environmental information, alleviate information asymmetry, and thereby obtain more bank loans, especially after the implementation of green finance policies [13].

Studies outside China have mostly addressed similar concepts and are relatively limited in number: Garcia-Sanchez, I.M., Hussain, N. et al. [14], based on 4076 firm-year observations from 829 companies across 24 countries, confirmed that the quality of corporate social responsibility (CSR) information disclosure facilitates access to financing channels. Moreover, external assurance of CSR reports further strengthens the relationship between the quality of CSR information and access to financial resources [14]. Mofoluwake Olulana (2025) [15] found that non-listed private small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) that disclose environmental information face lower levels of financing constraints compared to their peers. They are more likely to obtain external financing and overdraft protection, and the benefits of environmental information disclosure in alleviating financing constraints are greater in countries with higher levels of economic, financial, and institutional development [15].

Existing literature reveals that prior studies have primarily focused on all listed companies or heavily polluting industries, with no specific analysis dedicated to the steel industry. Research on explanatory variables has largely concentrated on overall ESG performance, with relatively few studies examining the individual “E” (environmental) component. Regarding the explained variables, most studies have only explored the cost of debt financing, lacking consideration of the impact on financing scale and financing structure. Furthermore, in-depth analyses in existing literature tend to rely on difference-in-differences models based on specific policies or conduct mediation and heterogeneity analyses. Therefore, this paper utilizes data from listed steel companies in China from 2014 to 2023 to examine the relationship between environmental information disclosure and debt financing, and to identify the time effect nodes. The contributions of this paper are as follows: 1. It focuses on the steel industry and extends the time span, conducting a ten-year study on the impact of environmental information disclosure on debt financing of steel enterprises; 2. Based on the “dual carbon” strategic goals, it employs a threshold effect model to examine the dual time-node effects of two environmental information disclosure-related policies introduced in China over the past decade—the Environmental Protection Law of 2015 and the 2021 Reform Plan for the Legal Disclosure System of Environmental Information.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 1: Introduction, which includes a comparative analysis of existing relevant literature and outlines the contributions of this study; Section 2: Theoretical analysis and research hypotheses; Section 3 and Section 4: Research design and related models, providing empirical results, robustness checks, and further research; Section 5: Conclusions and discussion, including policy recommendations and suggestions for future research.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Research Hypotheses

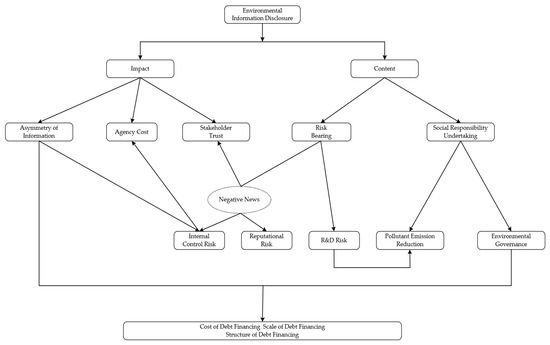

Environmental information disclosure can reduce the degree of information asymmetry, enhance creditors’ understanding of the enterprise, and alleviate the constraints on corporate debt financing (Figure 1). High information transparency can lower agency costs and strengthen stakeholder trust, thereby affecting corporate financing constraints [16]. Disclosed environmental information includes the enterprise’s risk exposure and social responsibility. Risk exposure encompasses internal control risk, reputational risk, and R&D risk, among which internal control and reputational risks are primarily triggered by negative disclosures, mainly referring to environmental penalties imposed on the enterprise. Environmental penalties indicate that the enterprise has failed to meet emission standards or has engaged in activities that severely harm the environment. For heavily polluting enterprises, the state imposes strict emission standards. Instances of non-compliant emissions suggest deficiencies in the enterprise’s internal regulatory system and potential flaws in internal controls, which increase corporate risk and, in turn, raise financing constraints. R&D risks in environmental information disclosure are reflected in the R&D investment in new processes and new procedures. Technological upgrades and transformations require substantial capital investment, and their success is uncertain, thereby posing R&D risks. The undertaking of social responsibility includes pollutant emission reduction and investment in environmental management. The better a company fulfills its social responsibilities, the lower its environmental risks, and the more favored it is by stakeholders, thereby reducing the company’s financing constraints [17].

Figure 1.

Influence Mechanism.

2.1. Environmental Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Costs

From the perspective of information asymmetry, disclosing environmental information can enhance transparency, improve corporate reputation, increase stakeholder trust, reduce the risk of adverse selection, improve the accuracy of risk predictions, and encourage creditors to lower loan interest rates, thereby reducing debt financing costs. Environmental information disclosure serves as the primary source for outsiders to understand a company’s environmental protection status. Research by Welker and Clarkson indicates that higher levels of information disclosure correlate with lower degrees of information asymmetry in debt financing costs. This results in more accurate predictions by investors regarding a company’s operational and financial status, which in turn reduces investors’ risk expectations and helps lower debt financing costs [18,19]. Schneider found that a company’s performance in environmental protection significantly negatively impacts debt financing costs; companies with poor environmental protection performance experience higher debt financing costs [20]. Bharath et al. discovered that companies with higher quality environmental information disclosure are more likely to gain the trust of creditors and have relatively lower debt financing costs [21]. Du, M., Chai, S., Wei, W. et al. [22] suggest that to mitigate the economic losses associated with the uncertainty of environmental risks, creditors may choose to increase debt costs. The strong development of green finance and the tangible presence of green credit make it easier for companies that disclose environmental information to secure low-cost bank loans [22].

From the perspective of signal transmission, enterprises aiming to enhance their advantages and mitigate the impact of environmental risks are more inclined to disclose environmental information that is difficult to replicate. This approach effectively communicates the current positive state of corporate environmental protection to stakeholders. Such disclosure helps enterprises establish a strong image, reduce risk levels, minimize analysts’ forecast errors, and lower creditors’ evaluation costs, ultimately decreasing corporate financing costs. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H1.

Environmental information disclosure is negatively correlated with the cost of debt financing.

2.2. Environmental Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Scale

Environmental information disclosure can partially reflect a company’s internal control risk, reputation risk, and R&D risk, which in turn affects creditors’ financing decisions. A lack of or insufficient environmental information disclosure may suggest that a company is facing high environmental risks, prompting creditors to withdraw some financing and thereby affecting the company’s financing scale [23]. From the perspective of cash flow liquidity, Diamond and Verrecchia proposed that enhancing the level of information disclosure can reduce information asymmetry within companies, improve investors’ accuracy in assessing corporate risk and value, lower risk estimates, and increase cash liquidity, thus expanding the scale of debt financing [24]. Bloomfield and Wilks reached similar conclusions [25]. Based on signaling theory, Goss and Roberts argued that corporate disclosure of environmental information can convey a positive development status to external stakeholders, facilitating easier access to debt financing in public markets and helping companies secure larger loans [26]. Domestic scholars Li Zhengda, Li Feng, and Zhao Yating believe that environmental information disclosure can enhance a company’s social reputation, optimize its investment structure, and increase trust from external financial institutions, thereby attracting more loans [27]. However, the environmental information disclosed by companies also includes negative aspects such as excessive emissions and environmental penalties. Regarding negative information, Barth and McNichols suggest that disclosing such information increases the credibility of the disclosure [28]. Companies that truthfully disclose environmental information demonstrate active participation in social responsibility activities, establishing an honest, trustworthy, and ethically strong corporate image, which is valued by stakeholders, especially lenders [29]. China’s environmental protection policies are becoming increasingly stringent, leading creditors to pay more attention to environmental information when assessing corporate risk. Some financial institutions, such as banks, have even implemented a one-vote veto system for non-compliance with environmental standards [30]. As the primary written medium for corporate environmental protection, environmental information can reduce information asymmetry, decrease the risk of adverse selection, and lower borrowing risks for creditors, making them more inclined to provide additional funding to enterprises. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypothesis:

H2.

Environmental information disclosure is positively correlated with the scale of debt financing.

2.3. Environmental Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Structure

At the current stage, the steel industry requires substantial financing not only for technological upgrades and industrial structure adjustments but also for ongoing environmental investments. Long-term loans offer more stability compared to short-term loans, but there is no consensus on how environmental information disclosure affects the term of debt financing. According to Huang Xiunu and Qian Lele, companies that disclose high levels of environmental information find it easier to secure long-term loans from commercial banks [31]. These banks decide on granting long-term loans based on the quality of a company’s environmental information disclosure [17]. By disclosing environmental information, companies enable creditors to better understand their environmental context and management level, which increases transparency, enhances corporate reputation, and reduces the difficulty of risk assessment, making creditors more willing to engage in long-term cooperation [32]. Environmental information disclosure significantly influences a company’s ability to obtain long-term bank loans. However, due to GDP growth pressures, some local governments, in pursuit of short-term economic gains, exert pressure on enterprises, thereby weakening the implementation of green credit policies [33]. Long-term debt financing carries higher uncertainty risks due to its extended term, leading banks to incur higher decision-making costs [34]. The weakening of green credit effects and the uncertainty of a company’s future development make banks and other creditors more inclined to issue short-term loans to mitigate credit risk. Steel enterprises face multiple pressures and require stable financial support. The increased difficulty in obtaining long-term loans has led many companies to opt for “short-term borrowing for long-term use” to meet their funding needs. Whether companies can more easily obtain long-term or short-term loans through environmental information disclosure remains inconclusive. Therefore, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a.

Environmental information disclosure is positively correlated with long-term loans.

H3b.

Environmental information disclosure is positively correlated with short-term loans.

3. Research Design

3.1. Model Design

To examine the relationship between environmental information disclosure and the cost of debt financing, Model (1) is constructed for empirical testing.

To explore the relationship between environmental information disclosure and the scale of debt financing, Model (2) is constructed for empirical testing.

To investigate the relationship between environmental information disclosure and the structure of debt financing, Model (3) is constructed for empirical testing.

CDF represents the cost of debt financing, DFR denotes the scale of debt financing, MS refers to the structure of debt financing, and EDI indicates the quality of corporate environmental information disclosure. Subscript denotes the firm, and denotes the year. , , and represent constant terms; , , and are the regression coefficients of the variables to be estimated. If , and are negative, positive, and positive, respectively, then hypotheses H1, H2, and H3 can be supported. Control represents all control variables; denote year fixed effects; represents the random error term. Robust standard error regression is employed to control for intra-group correlation and inter-group heteroscedasticity.

3.2. Sample Selection and Data Sources

This study focuses on A-share listed steel companies as the sample, covering the period from 2014 to 2023. Companies categorized under special treatments such as ST and *ST are excluded, along with those listed after 2014, and those undergoing business transformation, restructuring, or delisting. A total of 29 steel companies were identified by integrating data from the WIND database, CSMAR database, and academic literature. Data related to environmental information disclosure were manually collected from the China Securities Regulatory Commission, CNINFO, and company websites. Financial data were sourced from the WIND database, and money supply data were obtained from Eastmoney.com.

3.3. Variable Selection and Definition

3.3.1. Explained Variables

Cost of Debt Financing (CDF). Following the methodology of Li Guangzi and Liu Li [35], a company’s debt financing costs are measured by the ratio of its approximate financial expenses to total borrowings. These approximate financial expenses are derived from the sum of interest expenses, handling fees, and other financial expenses, which are itemized under the “Financial Expenses” account in the financial statements. Total borrowings encompass a company’s long-term borrowings, short-term borrowings, and long-term borrowings due within one year. Specifically, “Long-term borrowings” are classified under non-current liabilities, while “Short-term borrowings” and “long-term borrowings due within one year” fall under current liabilities, all presented on the balance sheet.

Scale of Debt Financing (DFR). Traditionally, the debt financing scale is often measured by the ratio of total borrowings (the sum of long-term and short-term borrowings) to total assets [36]. However, this sum does not accurately reflect the actual funds available to the enterprise. Consequently, in this study, the debt financing scale is quantified using the ratio of cash inflows from borrowings and bond issuance to average assets. These cash inflows are specifically identified within the ‘Cash Flows from Financing Activities’ section of the cash flow statement. Average assets, on the other hand, are computed as the arithmetic mean of the opening and closing balances of the ‘Total Assets’ item on the balance sheet.

Structure of Debt Financing (MS). Following the methodology of Yu Minggui [37], the debt maturity structure of a company is measured by dividing the sum of long-term borrowings and long-term borrowings due within one year by the company’s total liabilities. The company’s total liabilities, as presented on the balance sheet, are calculated as: Total Liabilities = Total Current Liabilities + Total Non-Current Liabilities.

3.3.2. Explanatory Variables

Environmental Information Disclosure (EDI). The content scoring method is a commonly used approach to measure the quality of environmental information disclosure. This paper adopts the methodology of Ye Chengang [38], with reference to the environmental information disclosure evaluation system developed under the National Social Science Fund Project “Research on the Environmental Responsibility Information Disclosure System of Chinese Enterprises.” Taking into account the characteristics of the steel industry, the quality of environmental information disclosure by listed companies is assessed from two dimensions: materiality and adequacy. As shown in Table 1, disclosure method, disclosure medium, and disclosure level represent materiality, while adequacy encompasses environmental management, environmental costs, environmental liabilities, environmental investment, environmental governance, government supervision and institutional certification, third-party oversight, and environmental assets, comprising a total of 11 primary indicators and 33 secondary indicators. The specific operational steps are as follows: 1. Score the secondary indicators: assign 0 points for non-disclosure, 1 point for qualitative disclosure only, and 2 points for both qualitative and quantitative disclosure. 2. Sum the scores using equal weighting. 3. Add 1 to the total score and take the natural logarithm to obtain the environmental disclosure index (EDI), i.e., EDI = Ln(1 + environmental disclosure score).

Table 1.

Environmental Information Disclosure Model.

3.3.3. Control Variables

Due to the limited sample size, this paper selects as many control variables as possible. Firm size represents the financial strength of a company to some extent, often making it more favored by creditors and allowing it to secure better financing conditions. A company’s profitability, solvency, operational capability, and growth potential all influence debt financing to varying degrees. A company’s loan credit directly affects the cost, scale, and structure of debt financing. Earnings per share can predict a company’s profitability and potential for growth, thereby influencing its debt financing. Differences in credit and resource access between state-owned and non-state-owned enterprises impact creditors’ financing choices. The type of audit opinion can preliminarily assess the accuracy of a company’s information, influencing risk prediction and consequently affecting the company’s debt financing. Monetary policy can affect loan interest rates, which directly influence the cost of debt financing. Tight monetary policy makes creditors more cautious, raising selection criteria for long-term and large-scale loans. Amarna and Garde Sánchez argue that companies providing earnings information signal responsibility and accountability, enhancing their reputation, which serves as a reputation guarantee in debt contracts, reducing the risk borne by creditors and affecting corporate bond financing [39]. The publication of an independent social responsibility report affects environmental information disclosure and also influences creditors’ sensitivity to information, potentially leading to adverse selection risks, thereby impacting debt financing. Therefore, the control variables in this paper are as shown in Table 2:

Table 2.

Variable Definition Table.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

This paper examines data from 29 steel companies over a period of 10 years, resulting in a sample size of 290. The maximum cost of debt financing (CDF) is 5.190, highlighting the high cost of debt financing in the steel industry. Some companies incur costs up to five times higher to secure funds through borrowing, leading to a very high cost of capital usage. The minimum value is 0. Along with the minimum values of debt financing scale (DFR) and debt financing structure (MS) also being 0, this suggests that the current development of the steel industry is constrained. Most companies have shifted from marginal profits to losses. The most likely reason for the minimum value being 0 is that some companies are unable to secure debt financing, whether for long-term or short-term borrowing, though the possibility of having sufficient self-owned funds cannot be excluded. The mean cost of debt financing exceeds the median, indicating that companies with high financing costs are predominant among the sample. The maximum debt financing scale is 3.25, with a minimum of 0, indicating that while some companies in the sample have strong debt financing capabilities, others cannot secure debt financing. The average debt financing structure is 11.6%, suggesting that few companies in the sample have obtained long-term loans. The maximum value of environmental information disclosure (EDI) is 53, the minimum is 3, and the standard deviation is 13.4, indicating a significant disparity in the level of environmental information disclosure among the sample companies. Regarding control variables, the company size (SIZE) is relatively large, most audit opinions (AUD) are standard unqualified opinions, state-owned enterprises are predominant, but the level of earnings management is low, and loan credit (TANG) is relatively high. This may be due to the fact that the sample companies hold a large amount of inventory, as China’s steel companies are currently in a phase of inventory reduction and structural adjustment. Specific data can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics Table.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

To test for the presence of multicollinearity among the selected variables, this study conducts Pearson correlation analysis. The correlation coefficient tables are presented in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6. Environmental information disclosure is negatively correlated with the cost of debt financing and positively correlated with the scale and structure of debt financing, which is generally consistent with the previous hypotheses. As the correlation coefficients among all variables in the tables are below 0.5, it indicates that multicollinearity is not a significant concern, and further analysis can be conducted.

Table 4.

Environmental Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Costs.

Table 5.

Environmental Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Scale.

Table 6.

Environmental Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Structure.

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.3.1. Cost of Debt Financing

The regression results in the first column of Table 7 show that the disclosure of environmental information by steel enterprises is significantly negatively correlated with the cost of debt financing at the 1% level, confirming Hypothesis 1. The size of the enterprise does not significantly impact the cost of debt financing. As previously analyzed, listed steel companies are generally large, with some size differences, but these differences are not substantial. Under the pressures of supply-side reform and environmental governance, enterprise development is hindered. When size differences are not significant, the size of the enterprise does not influence the effect of environmental information disclosure on the cost of debt financing. The profitability of the enterprise is significantly negatively correlated with the cost of debt financing at the 1% level. Whether an enterprise publishes an independent environmental report or a social responsibility report is significantly negatively correlated with the cost of debt financing at the 5% level, aligning with the current environmental conditions faced by steel enterprises. The comprehensive promotion of clean production, the large-scale elimination of outdated production capacity, and the full implementation of the “Blue Sky Protection Campaign” have resulted in large-scale losses in the steel industry. Creditors of enterprises with strong profitability may opt to lower loan interest rates, thereby reducing the cost of debt financing for the enterprise. The strictness of environmental regulations makes the disclosure of environmental information increasingly important. Independent reports can enhance creditors’ sensitivity to information, potentially lowering the risk assessment of such enterprises, reducing loan interest rates, and consequently lowering the financing costs for the enterprise. The nature of the enterprise has no significant effect on the cost of debt financing, indicating that “implicit credit” such as that of state-owned enterprises is difficult to function independently. In summary, this suggests that the cost of debt financing for steel enterprises is more concerned with the enterprise’s environmental transparency, the credibility of environmental information, and the enterprise’s profitability.

Table 7.

Baseline Regression Results.

4.3.2. Debt Financing Scale

As shown in the second column of the table above, there is a significant positive correlation between environmental information disclosure and the scale of debt financing at the 1% level, confirming Hypothesis 2. Disclosing environmental information can enhance transparency, build a positive corporate image, improve reputation, increase creditors’ understanding of the enterprise, reduce estimated risks, and enable the enterprise to secure larger loans. Both enterprise size and profitability are significantly positively correlated with the scale of debt financing at the 1% level. Larger enterprises with stronger profitability can obtain more loans. Currently, the steel industry is experiencing poor profitability and significant environmental pressures, prompting creditors to be more cautious in granting loans. They tend to prefer enterprises with stronger profitability and relatively larger scale, which can secure more financing; The nature of equity in steel enterprises also has no significant impact on the scale of corporate debt financing.

4.3.3. Debt Financing Structure

As shown in Column 3 of Table 7, environmental information disclosure is significantly positively correlated with the debt financing structure at the 5% level, thereby confirming Hypothesis 3a, which states that environmental information disclosure can increase a company’s long-term borrowings. However, the solvency of enterprises is significantly negatively correlated with the financing structure at the 10% level, and operating capability is significantly negatively correlated with the debt financing structure at the 5% level. The stronger the solvency and operating capability of steel enterprises, the faster the capital turnover and the stronger the repayment ability, leading creditors to prefer short-term borrowings characterized by “low risk and quick recovery.” At the same time, companies have a greater demand for “flexible and short-term” funds, resulting in a lower proportion of long-term debt. Corporate loan credit is significantly positively correlated with the financing structure at the 5% level. The better the loan credit, the easier it is to obtain long-term borrowings.

The regression results of Table 7 confirm Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3a, indicating that environmental information disclosure impacts an enterprise’s debt financing. However, enterprise size only affects the financing scale, and the equity nature of state-owned enterprises provides an advantage only in obtaining long-term loans. This sufficiently demonstrates the current financing situation of the steel industry in China. Overcapacity, intense domestic and international competition, and significant environmental impact, including resource destruction and pollution, show that the extensive production model is not compatible with sustainable development. It is imperative to change the production model and enhance efforts in environmental protection.

4.4. Further Analysis

The threshold effect model is an econometric method used to capture nonlinear relationships between variables. Its core concept is that when a certain “threshold variable” (such as time, policy intensity, or firm characteristics) reaches a specific threshold value, the direction or magnitude of the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable may undergo a structural shift. In this study, the threshold variable is “time,” and the objective is to determine whether the impact of environmental information disclosure on debt financing (costs, scale, and structure) of steel enterprises changes significantly at specific time points (policy implementation). The threshold effect model enables the quantification of differences in impact across different time periods and reveals the dynamic effects of policy implementation. Differences in policy intensity and enforcement strength may lead to nonlinear effects of environmental information disclosure on debt financing at different stages, which necessitates the use of threshold estimation to capture such stage-specific variations.

From the analysis above, it is clear that environmental information disclosure is negatively correlated with the cost of debt financing and positively correlated with the scale and structure of debt financing. However, it remains uncertain whether there is a temporal effect between environmental information disclosure and corporate debt financing in the steel industry over the past decade, and in which year it is more significant. This paper uses the threshold effect model for testing, employing the Bootstrap resampling method to calculate the p-value, with 1000 repetitions and a trimming proportion of 0.05. The results are shown in Table 8.

Table 8.

Threshold Test Results.

The impact of environmental information disclosure on the cost of debt financing in steel enterprises shows a single threshold effect over time, with the threshold year being 2021. In contrast, its impact on the scale and structure of debt financing shows a double threshold effect over time, with threshold years being 2015 and 2021. The 2015 revision of the “Environmental Protection Law of the People’s Republic of China” was the first to legally clarify the obligation of enterprises to disclose environmental information, especially for key pollutant discharging units. The “Reform Plan for the Disclosure System of Environmental Information According to Law” issued in 2021 further established a systematic disclosure framework, expanded and clarified the scope of disclosure subjects, and mandated the disclosure of content covering 11 key types of information, including pollutant emissions, carbon emissions, and ecological environment emergencies. Both policies involve the steel industry, which is characterized by severe environmental pollution and overcapacity. It is widely recognized that the cost of financing in China’s real economy is high [40]. The revised “Environmental Protection Law” is considered a soft policy and cannot significantly reduce the cost of debt financing in the short term. In contrast, the “Reform Plan for the Disclosure System of Environmental Information According to Law” is more specific in its requirements, stricter in disclosure, and more forceful in its enforcement, resulting in a more significant implementation effect.

4.5. Endogeneity Test

While the quality of environmental information disclosure affects a firm’s debt financing costs, debt financing scale, and debt financing structure, firms with lower debt financing costs and higher debt financing scale and structure tend to achieve higher environmental information disclosure scores, thereby giving rise to a bidirectional causality issue. Moreover, the relationship between a firm’s environmental information disclosure quality and its debt financing costs, scale, and structure may be influenced by other unidentified factors. In addition, considering the endogeneity issues arising from model specification, sample selection, and other factors, this study employs the instrumental variable approach to mitigate the impact of endogeneity on the research conclusions.

The results are presented in Table 9. This study introduces two instrumental variables: First, following Liao Guoping and Wang Wenhua (2023), the lagged one-period EDI performance (L.EDI) is used as an instrumental variable, and the 2SLS method is employed to test for endogeneity in the model [15]. Second, the average environmental disclosure quality score (EDI_m) of other firms in the steel industry in the same year is used as an instrumental variable [38] for 2SLS regression analysis.

Table 9.

Instrumental Variables Method.

Columns (1)–(4) present the regression results using the one-period lagged EDI as an instrumental variable. To test the validity of the instrumental variable, underidentification and weak instrument tests were conducted. The results show that the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic is 60.006 with a p-value of 0.000, indicating no underidentification issue. In addition, the Kleibergen-Paap Wald rk F statistic is 106.109, which is significantly greater than the 10% critical value of 16.38, thus rejecting the null hypothesis of weak instruments. Therefore, the use of the one-period lagged EDI as an instrumental variable is reasonable and valid. In the first stage, the regression coefficient of the instrumental variable is 0.667 and is statistically significant at the 1% level. In the second-stage regression, the coefficients of the fitted value of EDI on CDF, DRF, and MS are significantly negative at the 1% level, significantly positive at the 1% level, and significantly positive at the 5% level, respectively. This indicates that the quality of environmental information disclosure can significantly reduce the cost of debt financing, expand the scale of debt financing, and increase the level of long-term debt, which is consistent with the previous regression results and further confirms the robustness and reliability of this study’s findings.

Columns (5)–(8) present the regression results using EDI_m as the instrumental variable. This instrumental variable passes both the under-identification test and the weak instrument test, indicating that using the average EDI of other firms in the steel industry in the same year as an instrumental variable is reasonable and valid. In the first stage, the regression coefficients of the instrumental variable are all statistically significant at the 1% level. In the second stage regressions, the coefficients of the fitted value of EDI on CDF, DRF, and MS are significantly negative at the 1% level, significantly positive at the 1% level, and significantly positive at the 5% level, respectively. This suggests that the quality of environmental information disclosure can significantly reduce the cost of debt financing, expand the scale of debt financing, and increase the level of long-term debt. Therefore, after addressing endogeneity by introducing the instrumental variable, the previous regression results remain robust.

4.6. Robustness Test

To verify the robustness of the results, this paper uses variable substitution for validation. The ratio of financial expenses to total liabilities serves as a proxy for the cost of debt financing. The ratio of the sum of long-term loans, short-term loans, and short-term loans due within one year to average assets is used as a proxy for the scale of debt financing. The ratio of average long-term loans to total loans is used as a proxy for the structure of debt financing [41,42]. The regression results confirm Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, and Hypothesis 3a, with some variables even showing higher significance than previously reported results. The conclusions drawn in this paper are robust and reliable. The specific regression results are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Robustness Test.

5. Conclusions, Discussion and Policy Recommendations

5.1. Research Conclusions

This study examines 29 listed steel companies, analyzing their environmental and financial information over a 10-year period from 2014 to 2023 to investigate the impact of environmental information on corporate debt financing. The main research conclusions are as follows:

(1) There is a negative correlation between environmental information disclosure and the cost of debt financing for steel companies. This disclosure includes details on the generation, emission, and treatment of major pollutants, as well as information on the purchase of equipment and the development of new processes for cleaner production. Such transparency significantly enhances creditors’ understanding of the company, reduces risks associated with external environmental governance, and lowers the cost of corporate debt financing.

(2) Environmental information disclosure is positively correlated with the scale of debt financing for steel companies. With certain control variables in place, environmental information disclosure significantly affects the scale of debt financing at the 1% level. Fully disclosing environmental information externally can enhance a company’s reputation, increase the credibility of disclosed information, and boost creditors’ trust in the company, thereby enabling the company to secure more debt financing.

(3) Environmental information disclosure is positively correlated with the debt financing structure of steel companies. Disclosing environmental information helps companies obtain more long-term loans. Corporate size and profitability do not impact the debt financing structure, indicating that under strict environmental regulations, environmental information has become a key non-financial factor that creditors focus on. Companies that disclose environmental information are more likely to secure long-term loans.

The findings of this study are consistent with previous research on related topics; however, new insights are presented in terms of research subjects, research content, and further analysis. Regarding the research subjects, prior studies have primarily focused on all listed companies or all heavily polluting listed companies, without specifically targeting the steel industry. This study is more targeted and thus more applicable to steel enterprises. In terms of research content, existing studies have generally measured financing constraints solely through financing costs, while this study incorporates financing scale and financing structure. In the further analysis, this study adopts a threshold effect model that is more suitable for small-sample analysis, extends the time span, and verifies the time effect of environmental information disclosure. This paper also has two limitations: First, due to the limited number of listed companies in the steel industry and the relatively high proportion of continued ST and *ST companies, the sample size in this study is only 29, which may lead to small sample bias. Second, differences in the time frame of research may result in conclusions that are inconsistent with those of this paper.

Given the length constraints of the paper, future research could continue to explore the following scenarios: 1. The impact mechanism of environmental information disclosure by steel enterprises on debt financing, with the potential inclusion of easing financing constraints and reducing corporate risk exposure as mediating variables. 2. With the rapid development of AI technology, leading steel companies such as Baoshan Iron & Steel Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) have begun to implement AI-based environmental reporting systems, and Shougang Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) has established a blockchain-based energy consumption platform. Future studies could categorize the 29 steel companies based on whether they adopt AI technology and conduct further heterogeneity analysis to examine whether AI technology enhances the quality of environmental information disclosure and alleviates debt financing constraints. 3. Future research may explore the impact of peer effects, investigate whether the disclosure practices of other companies influence the research results, and examine the underlying mechanisms of these effects. It may also consider additional factors such as media influence, public environmental awareness, and greenwashing behavior [43,44].

5.2. Policy Recommendations

With global climate warming and accelerated glacier melting, there is increasing global emphasis on environmental protection. The convening of international environmental conferences, the release and implementation of domestic environmental policies, and the “dual carbon” policy background have led to increasingly stringent environmental regulations in China. The steel industry, as a heavily polluting sector and having consistently ranked first in global steel production, has become a focal point for environmental protection. Amid overcapacity and fierce competition, the industry faces additional constraints from environmental regulations, and the issue of debt financing has become prominent. This study finds that environmental information disclosure can alleviate financing constraints for steel enterprises and proposes the following recommendations:

(1) Steel enterprises should publish standalone environmental reports or social responsibility reports. Independent environmental reports can provide clear informational guidance for creditors, accurately reflect the enterprise’s environmental data, help creditors understand the enterprise’s environmental protection performance, and reduce the enterprise’s financing constraints. Where necessary, all listed steel companies may be required to mandatorily connect to the national unified disclosure system.

(2) Steel enterprises should fully disclose environmental information. Full disclosure means that enterprises should not only include information on pollution emissions, pollution fees, emission reduction costs, and any environmental penalties, but also provide details on the operation of clean production facilities, such as which new clean facilities have been added, which outdated equipment has been eliminated, and whether new energy-saving and emission-reduction technologies are being developed. This information allows external investors to comprehensively understand the efforts made by enterprises for environmental protection and to track the direction of non-operating funds, enabling better risk prediction, which helps enterprises reduce financing costs, expand financing scale, or improve financing structure.

(3) Steel enterprises should disclose more “hard indicators.” “Hard indicators” refer to metrics with specific numerical values or amounts, such as a company’s investment in environmental protection, technological research and development, total pollutant emissions, total emission reductions, and profits gained from environmental reforms. These indicators can be quantified, making them more credible. For creditors, quantified indicators are also easier to verify. For companies, disclosing quantified indicators is more difficult to imitate, distinguishing them from textual disclosures.

(4) Establish a dynamic regulatory control mechanism across the entire chain. To ensure the authenticity and effectiveness of environmental information disclosure, a multi-dimensional, full-process regulatory system must be established: integrate pollutant discharge monitoring data from ecological and environmental authorities, financing records from financial regulatory bodies, and environmental tax payment information from tax authorities to build a cross-departmental data-sharing platform linking “environmental protection—finance—taxation.” At the same time, environmental information disclosed by steel enterprises must be audited by qualified third-party institutions, which shall bear joint and several liability for the authenticity of the data.

(5) Leveraging AI technology to enhance the intelligence and accuracy of environmental information disclosure. The rapid development of AI technology has greatly facilitated social production and daily life. Steel enterprises can utilize artificial intelligence (AI) to build intelligent environmental information disclosure systems. Through machine learning algorithms, environmental data (such as pollutant emissions, energy consumption indicators, and environmental protection investments) can be collected, analyzed, and visualized in real time, thereby improving the efficiency and quality of environmental information disclosure. Specifically: first, in terms of data governance, AI models can be used to automatically calculate and verify “hard indicators” such as environmental costs and environmental liabilities, reducing manual processing errors and ensuring the accuracy and timeliness of quantitative data such as total pollutant emissions, emission reduction progress, and the operating efficiency of environmental protection equipment, thereby enhancing creditors’ trust in the disclosed information; second, intelligent risk assessment and forecasting can be carried out. By analyzing historical environmental data and industry policies with AI, potential environmental risks (such as risks of environmental penalties and excessive carbon emissions) can be identified and dynamically disclosed in environmental reports along with corresponding mitigation measures, providing creditors with a more comprehensive basis for risk anticipation and reducing the financing cost premium caused by information asymmetry; finally, AI technology can significantly improve the quality and credibility of environmental information disclosure through automated data collection (e.g., using blockchain technology to monitor energy consumption and ensure data immutability), real-time analysis (e.g., NLP-based text mining), and intelligent forecasting (e.g., environmental risk models).

Author Contributions

H.Z.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing—Original draft, Visualization. X.L.: Investigation, Data curation, Validation; H.L.: Writing—Review and Editing, Supervision and made suggestions to improve the quality of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Philosophy and Social Science Research Project of Jiangsu Province Universities [No. 2022SJYB2275] and the Zhenjiang Social Science Applied Research Project [No.2022YBL010].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Margerison, J.; Fan, M.; Birkin, F. The prospects for environmental accounting and accountability in China. Account. Forum 2019, 43, 327–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J. Policy Recommendations on Green Finance and Transitional Financial Support for the Green and Low-Carbon Development of Steel Enterprises. Enterp. Reforrm Manag. 2024, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Research on Financing Preferences of Chinese Steel Enterprises. Metall. Account. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, R. Research on Debt Issues in China’s Steel Industry from the Perspective of Supply-Side Structural Reform. Ph.D. Thesis, Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, Shanghai, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Cui, G.; Zheng, M. Does green credit policy affect corporate debt financing? Evidence from China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 5162–5171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y. The Impact of Environmental Constraints on Corporate Debt Financing. J. Univ. Chin. Acad. Soc. Sci. 2024, 44, 43–69+161. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y. Does the Environmental Protection “Fee-to-Tax” Reform Affect Corporate Debt Financing Costs?—A Quasi-Natural Experiment Based on the Environmental Protection Tax Law. China Environ. Manag. 2025, 17, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Sun, Y. Corporate ESG Performance and Debt Financing Costs. J. Guizhou Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024, 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, M.; Wang, J. Research on the Relationship among ESG Performance of Heavily Polluting Enterprises, Media Supervision, and Financing Costs. Sci. Decis. 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Chen, L.; Gou, D. The impact of corporate environmental disclosure quality on financing constraints: The moderating role of internal control. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 30, 33455–33474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, H.; Ran, C.; Gao, Y. Does ESG information disclosure increase firm value? The mediation role of financing constraints in China. Res. Int. Bus. Finance 2024, 73, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Shi, Z.; Lei, F.; Sun, W.; Zhang, J. Effect of Environmental Information Disclosure on the Financing Efficiency of Enterprises-Evidence from China’s Listed Energy Companies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, P.; Peng, B. Does environmental credit affect bank loans? Evidence from Chinese A-share listed firms. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2025, 30, 1225–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.; Hussain, N.; Martínez-Ferrero, J.; Ruiz-Barbadillo, E. Impact of disclosure and assurance quality of corporate sustainability reports on access to finance. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 832–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Wang, W. Environmental Information Disclosure, Corporate Investment Efficiency, and Green Innovation. Jiangxi Soc. Sci. 2023, 43, 90–101. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, R.; He, Y. A Study on the Dynamic Relationship between Environmental Information Disclosure and Financing Constraints—Empirical Evidence from Heavily Polluting Industries. J. Financ. Econ. Res. 2020, 35, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Zhu, L. Corporate Social Responsibility Information Disclosure and Debt Financing Costs—Empirical Data from Mainboard Heavily Polluting Listed Companies. Account. Commun. 2018, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, M. “Corporate Security Begins in the Community”: The Social Work of Environmental Management. In Enacting the Corporation: An American Mining Firm in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, P.M.; Overell, M.B.; Chapple, L. Environmental Reporting and its Relation to Corporate Environmental Performance. ABACUS A J. Account. Financ. Bus. Stud. 2011, 47, 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A. Bound to Fail? Exploring the Systemic Pathologies of CSR and Their Implications for CSR Research. Bus. Soc. 2020, 59, 1303–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharath, S.T.; Sunder, J.; Sunder, S.V. Accounting quality and debt contracting. Acc. Rev. 2008, 83, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Chai, S.; Wei, W.; Wang, S.; Li, Z. Will environmental information disclosure affect bank credit decisions and corporate debt financing costs? Evidence from China’s heavily polluting industries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 47661–47672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Appolloni, A.; Shahzad, M. Environmental administrative penalty, corporate environmental disclosures and the cost of debt. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 332, 129919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D.W.; Verrecchia, R.E. Disclosure, Liquidity, and the Cost of Capital. J. Financ. 1991, 46, 1325–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomfield, R.J.; Wilks, T.J. Disclosure Effects in the Laboratory: Liquidity, Depth, and the Cost of Capital. Account. Rev. 2000, 75, 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, A.; Roberts, G.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Finance 2011, 35, 1794–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, F.; Zhao, Y. The Financing Effect of Environmental Information Disclosure: Evidence from Heavily Polluting Enterprises. Audit. Econ. Res. 2024, 39, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Barth, M.E.; McNichols, M.F.; Wilson, G.P. Factors Influencing Firms’ Disclosures about Environmental Liabilities. Rev. Account. Stud. 1997, 2, 35–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Ruan, W.; Shi, H.; Xiang, E.; Zhang, F. Corporate environmental information disclosure and bank financing: Moderating effect of formal and informal institutions. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2022, 31, 2931–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Xu, H. Market-oriented Process, Environmental Information Disclosure, and Green Credit. Financ. Econ. Forum. 2011, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zha, L. Information Disclosure Quality and Debt Financing Choices of Listed Companies—An Empirical Analysis Based on Shenzhen Stock Exchange Information Disclosure Evaluation Data. Econ. Latit. Longit. 2019, 36, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, Y. Does Green Finance Policy Increase Corporate Debt Financing Costs? Secur. Mark. Her. 2023, 4, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Attig, N.; Rahaman, M.; Trabelsi, S. Creditors at the Gate: Effects of Selective Environmental Disclosure on the Cost of Debt. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2025, 33, 202–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Kong, L. Environmental Information Disclosure, Bank Credit Decision-Making, and Debt Financing Costs—Empirical Evidence from Heavily Polluting Listed Companies in the A-Share Market of Shanghai and Shenzhen. Econ. Rev. 2016, 147–156+160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, L. Debt Financing Costs and Discrimination against Private Credit. Financ. Res. 2009, 12, 137–150. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Li, T. Do Bank Loans Pay Attention to Corporate Environmental Information Disclosure? Account. Friend 2020, 106–112. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M.; Xia, X.; Zou, Z. Managerial Overconfidence and Corporate Aggressive Liability Behavior. Manag. World 2006, 104–112+125+172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, J.; Li, H. External Governance, Environmental Information Disclosure, and Equity Financing Costs. Nankai Bus. Rev. 2015, 18, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarna, K.; Sánchez, R.G.; López-Pérez, M.V.; Marzouk, M. The effect of environmental, social, and governance disclosure and real earning management on the cost of financing. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 3181–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, B. What Factors Determine the High Financing Costs of China’s Real Economy?—Empirical Evidence from the Three-Dimensional Corporate Debt Financing from 2005 to 2014. J. Cent. Univ. Financ. Econ. 2015, 28–36+94. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, Y.; Tong, L. Can Environmental Information Disclosure Alleviate Asset Mispricing? Financ. Regul. Res. 2023, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wei, Y.; Ji, M. A Study on the Impact of Environmental Protection Fee Reform to Taxation on Corporate Green Information Disclosure. Secur. Mark. Her. 2021, 8, 2–14. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Guo, F.; Du, Z. Learning from Peers: How Peer Effects Reshape the Digital Value Chain in China? J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ni, L.; Xu, Y. Enterprise Digital Transformation Drivers: Market or Government? A Case Study from China. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2025, 20, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).