Abstract

Increasing gender equality, United Nations Sustainable Development Goal Five (UN SDG 5), is one of many wicked problems that are difficult to solve in sport. Innovative policies may create a backdrop for improving women’s career outcomes in sport and beyond. This research aims to theorize and empirically demonstrate some of these contextual relationships. Using FIFA Women’s World Cup standings as outcomes, international analyses show that sustainability has real consequences for women and their countries’ success. Guided by wicked problems Literature explicitly recognizing complexities, this research considers the interconnectedness of the UN SDGs with a focus on sports. International empirical analyses demonstrate that leading countries’ more holistic sustainability policies help to address UN SDG 5. This study also compares sustainable development indicators in regression analyses to clarify how these composite measures relate to improved outcomes for women. Overall, future research should incorporate gender differences and thereby consider a broad set of sustainability factors.

1. Introduction

This article adopts the perspective that the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs) are interlinked wicked problems [1] and investigates illustrative relationships focusing on UN SDG 5, Gender Equality. McCune et al. (2023) [2] explain that wicked problems are highly complex, uncertain, and involve stakeholders with fundamentally different views, characterizing gender inequality [1]. This research suggests that this wicked problem involving women’s equality, empowerment, and ultimate success could be ameliorated by improving sustainability as per the UN SDGs.

A salient example of women’s increasing empowerment and success is the world’s excitement at watching women’s FIFA soccer [3]. Reflecting cultural norms of gender inequality, the sports world has generally been a place where men demonstrate their power and superiority, including over women, so this context is critical as we aim for gender equality [3,4]. In the 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup, Spain’s La Roja team won against England’s Lionesses, noticeably raising the status of women’s sports in the press [5]. The media used this prominent event to increase the salience of women’s unequal treatment in sports and the business of sports compared to men [6,7,8].

At this pinnacle moment of women’s empowerment, a 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup scandal, now dubbed the “kiss controversy”, ensued [9]. The games had empowered women around the world for an instant, but darkness loomed when the then-president of the Spanish Football Federation, Luis Rubiales, humiliated a soccer star, Jenni Hermoso. During the trophy ceremony, he grabbed her and kissed her suddenly on the lips without her consent on stage. Even worse, he later claimed his innocence instead of admitting to the obvious violation [10].

This research, seeking to illustrate the connectedness of the UN SDGs, including UN SDG 5, Gender Equality, uses the FIFA context because women’s soccer and recent events are symbolic of both women’s modern empowerment and opposing forces working against progress. The world implicitly recognizes that achieving gender equality is part of sustainability through inclusion in the world’s sustainable development goals as UN SDG 5, Gender Equality, and this research aims to find direct evidence of this.

The accomplishments of Spain and other top countries in women’s soccer inspire us to pay more attention to UN Sustainable Development Goal Five, Gender Equality, to improve sports, our businesses, other types of organizations, and institutions [11]. Examining the factors affecting women’s success in a world that needs their talents could spur business, policy, and institutional innovation that rethinks and changes conventional systems so they become more gender balanced [12,13]. This research shows that countries investing in innovations to increase sustainability, measured by some well-recognized UN measures including those geared to gender differences and the natural environment, are related to the relative success of a nation’s women, measured by FIFA outcomes. This research ties the holistic view of sustainability to improved women’s success, demonstrating the interconnectedness of the UN SDGs. Following recent Literature combining innovation and sustainability (the UN Sustainable Development Goals (UN SDGs)) for conceptual consistency [14], the definition of innovation adopted in this article is the same:

“Innovation is conceived as a means of changing an organization, either as a response to changes in the external environment or as a pre-emptive action to influence the environment [and thus can be] broadly defined to encompass a range of types, including new product or service, new process technology, new organization structure or administrative systems, or new plans or program pertaining to organization members.”[15], p. 694

Investments in sustainable innovative changes have to be made to improve conditions for women and develop organizations that benefit from this diversity [16,17]. Sustainability and gender equality are deeply linked because inclusive innovative policies ensure women’s participation in environmental, economic, and social decision-making. Creating conditions of more equitable resource distribution, climate resilience, and sustainable development supports women’s survival, at the very least [18]. Conversely, sustainability efforts that ignore gender often fail, as women are key agents of change in fostering long-term ecological and social balance [19]. Winning women’s sports teams such as those in the FIFA Women’s World Cup may present salient examples for analysis and learning as outcomes of progress in sustainable development. FIFA results enable transparent global comparisons. What are the changes in conditions necessary to see women succeed in sports, business, and more generally? Winning teams are proposed in this research as representative positive outcomes that may be associated with some of the United Nations’ country sustainability measures.

Previous organizational Literature has begun to examine successful women’s influence on sustainability, but there is limited research taking a broad reverse perspective of what national sustainability factors might support women’s success. For example, research found some moderating factors enabling women on top management teams in Asian firms to influence the implementation of firm environmental management systems and green innovations [16,20]. Some moderators included women directors sitting on corporate social responsibility committees, women executives’ power, and national institutional gender parity based on women’s representation in national parliaments and the labour force [16]. Other aligned research found that work toward the 2030 Agenda addressing the UN SDGs is more ambitious in companies having a woman as a CEO or chair of the board of directors [21]. Research supports proactive organizational policies explaining that women in high-status levels of management make a bigger difference for reducing the gender wage gap than simply promoting women to middle-level management positions [22].

Other previous research has generally discussed some of the ingredients required to build top international teams, such as developing team resilience, a composite measure of team leadership, learning, positive emotions, and social identity [23]. Research has holistically analysed factors influencing elite team development, categorizing these factors into micro (individual), meso, and macro levels [24]. De Bosscher et al. [24] summarize a number of studies stating that sports success owes a great deal to national systems and conditions. Factors affecting sports team success include the following: the GNI (gross national income), population size, the education system, athletic training resources (including many types of resources such as sports facilities, competitive programs, coaching, athlete’s lifestyle support, etc.), financial support for sports programs, private sector partnerships, a national tradition of the particular sport, a sports culture of excellence, sports media promotion, and an audience enthusiastic for world-class level achievements. This previous research does not consider gender differences, so while women’s sports teams likely need the same supports, more gender-specific research could be helpful. For example, some research suggests that involvement in sports is influenced by societal beliefs about gender roles, which could also influence the distribution of resources for women engaging in some of these activities [25,26]. At a high level, several development indicators tested in this research contain components that match many of the aforementioned support factors, as will be further expanded upon.

Policy research has also made contributions to this topic. Mandel and Semyonov [27] advise that directly addressing the gender wage gap is important. Other research suggests that public–private partnerships can be vehicles to improving gender equality and asks corporate executives to include gender considerations in corporate social responsibility activities [1]. Thus, bringing various types of stakeholders together, as suggested by UN SDG 17, Partnerships for the Goals, is critical for addressing gender inequality. Previous research also finds empirical evidence that economic development could be a factor supporting the type of institutional innovations necessary to move women toward their aims [17,20].

Gender inequality is an ongoing problem that is not being adequately addressed, even though it has been well known in human history across life experiences, careers, and countries [28,29,30]. The subject needs more research attention, and there is a general consensus since the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals includes this issue as Goal Number Five, titled “Gender Equality” [11]. This inequality that violates human rights standards, hampering women’s power in society and their careers, also has consequences broadly through the underutilization of talent and other related social consequences that are prevalent but unrecorded, such as human trafficking [31,32].

In so many ways, our world lacks balance, and patriarchy leaves us with many challenges [30,33,34]. The world’s problems are complex wicked problems that are multidimensional, and so solutions are not clear [2,35,36]. Thus, although the imbalance of patriarchy is obvious, additional compounding factors interfere, and it is thereby hard to pinpoint the extent of and then effectively address the patriarchal governance factors [17,37]. Previous research suggests that more systematic types of methods are needed to address this issue. This research responds to that call with empirical analyses and insights derived using an evidence-based approach [1].

As compared to previous research, this work offers a higher-level holistic view using international measures that may direct future research toward finding generalizable factors addressing the wickedness. This research looks into why some countries develop winning women’s sports teams in a world where professional sports is male-dominated and women are challenged when they step out of stereotyped gender roles [21,38,39]. If these countries can conquer this stubbornly patriarchal issue, they must be doing something correct with respect to creating better conditions to improve gender equality [40,41,42].

In this examination, international measures are usefully compared for application across research areas. To reduce gender inequality in all domains, the condition of women needs to be incorporated broadly across research that tends to ignore it [43]. The measures tested include one that might be expected, the Human Development Index (HDI), a couple that might be expected to be aligned with the context, the Gender Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Inequality Index (GII), and one that could be unexpected if this were not viewed as a wicked problem, the Planetary pressures-adjusted HDI (PHDI) [44] (Please see Table 1).

Table 1.

Description of key measures.

Correspondingly, this research sheds light on factors that affect gender equality, examining it as a wicked problem that needs holistic solutions in accordance with sustainable development. Business, including the business of sport, is a critical partner in addressing the sustainable development goals, especially today as institutional shareholders recognize the benefits of women’s talents as leaders on management teams [45], However, gender equality is required if women are to gain the necessary experience and rise in the ranks [14,16,21,37]. The next sections develop hypotheses, test them with an international data set in regression analyses, discuss results, and conclude.

2. Theory and Hypotheses

2.1. The HDI Is Related to Women’s Success

Previous research has extensively discussed the challenges women have engaging in teams, whether as players on women’s sports teams, as sports coaches and managers of women’s teams including soccer, or in top management teams [16,46,47]. Organizational teams, especially leadership teams, drive strategic decision-making, innovation, and performance in businesses [48]. Studying women’s sports teams offers unique insights into collaborative leadership, resilience, and inclusive team dynamics—key factors for organizational success [49]. By analysing these teams, scholars can uncover best practices for fostering diversity, equity, and high-performance cultures in all organizations [48,50].

More broadly, Literature recognizes the barriers women face across many male-dominated industries, whether to simply gain entry-level positions, obtain promotions once having developed a career, or lead [13,51]. Playing soccer and building professional women’s teams in a male-dominated sports industry has taken women’s leadership to overcome barriers. Given these efforts and hard-won successes, understanding the conditions for women’s successes has been of interest in organizations’ Literatures so as to create innovative policies to sustain circumstances from past wins [20,51]. For example, mentoring, networking, and cultures of belonging can be embedded into organizational practices and policies for continued creation of opportunities for women and their long-term career growth [12,51].

No matter the tremendous efforts of previous research and the application of those learnings, women are still falling behind within patriarchal systems, so more research is required to continue this line of inquiry [21,52,53]. Correspondingly, this research adds to the search for and discovery of supportive conditions for women in sustainability because sustainability is holistic, recognizing the complexity and interrelatedness of our human-created systems, and inclusive of gender equality. Embedded in the concept of sustainability is a long-term view considering the conditions for future generations, so making the long-term investments to see women’s success in sports and beyond is then viewed as valuable [54,55]. These investments could include equal pay and equal access to leadership roles and participation, thereby fostering greater fairness, empowerment, and equal representation for all genders [56,57]. This research tests whether and which types of sustainability conditions as reflected by certain development measures from the United Nations Development Programme correspond to positive outcomes for women, using the Women’s World Cup standings.

Typically, the Human Development Index (HDI) is popularly used in research to reflect a broader measure of wealth of a country as compared to gross domestic product (GDP) [58,59]. A higher HDI is normally expected to reflect better living conditions in a country, so this measure is a starting place for this research. Please see Table 1 for a listing of several measures discussed in the following paragraphs, including the HDI. The table provides explanations of the measures and notes related to this research so the variables of interest may be more easily understood and compared.

The HDI suggests the connectedness of better national conditions, or a higher standard of living, to sustainable development; no matter that it misses many aspects of what are discussed as sustainable country conditions [11,58]. The HDI includes education, health, and economic wealth, so in a basic way, it covers some broad aspects of sustainable development, including the social and economic but largely missing the environmental ones, perhaps included indirectly when recognizing the relationships between human and environmental health [60].

No specific gender components are included in the HDI, but indirectly, one could argue that there are gender-related measures. Average achievement in life expectancy, which is the HDI health measure, and education, although measured no matter the gender in the HDI, would still have to include females in the population [61]. Thus, although the HDI lacks any specific national factors directed specifically at enhancing women’s experiences, countries that are broadly investing in education and health may be better places for fostering women’s success than others that are not. The following hypotheses tests this view.

H1.

Women’s soccer team success is positively related to the Human Development Index (HDI).

2.2. The Gender Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Inequality Index (GII) Are Measures Aligned with Women’s Success

Development measures for gender include the Gender Development Index (GDI) and the Gender Inequality Index (GII) [62]. A higher HDI may logically predict positive outcomes for women, as above, but if these other measures are meaningful, they should at least be related to women’s outcomes.

First, the GDI is considered and compared with the HDI. Limited previous research has incorporated the GDI [31,63]. Cameron et al. [31] found a correlation between the GDI and the number of human trafficking legal cases in a country. They suggest that higher rates of legal cases may be associated with stronger anti-trafficking laws, which would tend to benefit women. Carlsen [63], like the present research, used gender development indicators to identify and discuss countries’ differences in gender development. The GDI is a measure of women’s inequality, a ratio of female HDI divided by male HDI. Like the HDI, it uses the same three categories but calculated on a gender relative basis: health (comparing female and male life expectancy at birth), education (comparing female and male expected years of schooling for children and female and male mean years of schooling for adults ages 25 years and older), and economic power (comparing female and male estimated earned income) [64]. Thus, among other issues, the GDI captures the gender wage gap, and while composite measures are believed to be most effective when they include only a few variables, they are also limited and could miss capturing some significant aspects of gender inequality [65,66]. Still, the GDI is a gender-adjusted HDI ratio and should be a predictor of women’s success, as measured by Women’s Cup Soccer scores. If the GDI is a positive measure of development and the outcome is women’s success, then GDI may also be a stronger predictor than HDI.

Next, the GII is a composite measure representing gender disadvantages across reproductive health, empowerment, and the labour market [67]. Reproductive health in the GII is composed of a maternal mortality ratio and an adolescent birth rate. Empowerment is measured by having at least a high school education and the share of female and male political representation in terms of the numbers of parliamentary seats. The labour market is measured by female labour participation rates. A country aims for a lower GII to indicate low inequality between women and men. Where the GDI is considered a measure of average achievement, the GII is considered a measure of inequality in achievement [63]. GII has been criticized for being overly complicated [68] but has been implemented widely in research [44,69,70,71]. Since the GII includes aspects that would likely be related to women’s success, especially empowerment, which is distinctly different from the GDI, it is expected to be related to Women’s Cup Soccer scores. However, being a measure of disadvantage rather than advantage, it may not have as strong a relationship with women’s soccer success as would the more positive GDI measure of average achievement. The following hypothesis relates greater gender development and equality with women’s soccer success.

H2.

Women’s soccer team success is positively related to greater gender development and equality as measured by gender-adjusted development and inequality indexes (GDI and GII).

2.3. The Natural Environment Affects Women’s Success

A relationship that may be less obvious is that the condition of the natural environment affects women’s success [44]. Sustainable development is a helpful holistic perspective including social aspects, such as gender equality, and environmental issues, such as climate change, but it has been broken down into separate components. Sustainable development is often discussed as having social, environmental, and economic aspects, summarized by “People, Planet and Profits” [72,73]. According to the 1987 Brundtland report ‘Our Common Future’, sustainable development is “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” [54]. This holistic and timeless definition implies intertwined relationships among the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals related to a 2030 Agenda [11]. The goals cover many world issues, and because they are separately stated goals, they are sometimes viewed and investigated separately. However, research has recognized the interrelatedness of the goals, including Goal #5, Gender Equality, understanding that the holistic definition of sustainable development is the binding backdrop for these interconnected and wicked issues that need complex solutions and special environments for developing the solutions [1,36,74].

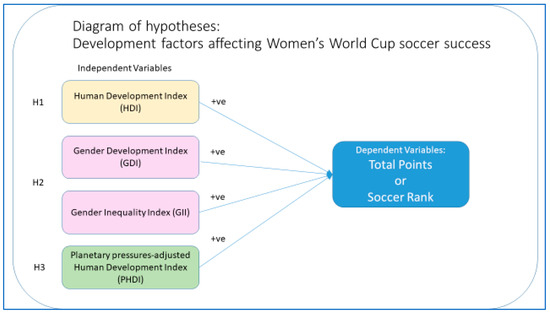

Previous Literature has discussed the relationship between the natural environment and human development, including gender [75,76,77]. This research intends to show consistency with these ideas that even women’s soccer scores are positively related to the Planetary pressures-adjusted Human Development Index (PHDI). The PHDI is calculated by reducing a national Human Development Index by higher production-based carbon dioxide emissions per capita and material footprint per capita. Thus, environmental conditions affect human development in this measure [78]. Research suggests that women are particularly disadvantaged by poor and changing environmental conditions because of the unequal conditions that they start with [79,80]. For example, they have less power to remove themselves from situations of environmental deterioration affecting agricultural livelihoods [81]. Recognizing that sustainable development is made up of connected wicked problems, the next hypothesis relates women’s soccer team success with the Planetary pressures-adjusted HDI. See Figure 1 for a diagram of the hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Diagram of hypotheses.

H3.

Women’s soccer team success is positively related to the Planetary pressures-adjusted HDI (PHDI).

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Data and Variables

The data sources include the World Development Indicators from the World Bank, United Nations Development Programme (2021/22) [61,64,67,78,82], and FIFA’s Women’s Ranking for June 2023 [83]. The two dependent variables used are measures of the soccer success of each women’s FIFA team: (1) their total soccer points, called Total Points, and (2) the soccer rank, called Soccer Rank. Both are used in similar regression analyses, with a sample size of 188 national women’s team’s outcomes, to cross-check the consistency of the results. The 2023 FIFA Women’s World Cup was held with 32 teams for the first time. The tournament marked a significant expansion compared to the 2019 edition, which featured only 24 nations. Australia and New Zealand qualified automatically as hosts, while 30 other teams secured their spots through a qualification process.

The main independent variables of interest include the Human Development Index (HDI), Gender Development Index (GDI), Gender Inequality Index (GII), and Planetary pressures-adjusted HDI (PHDI) [61,64,67,78]. These are composite measures composed of other measures, and some of the data are from different years (details can be found in United Nations Development Programme technical notes [62]).

The HDI is composed of life expectancy at birth, expected years of schooling (for children of school entering age), average years of schooling (for adults aged 25 and older), and gross national income (GNI) per capita based on purchasing power parity. So, the HDI roughly covers health, education, and standard of living [61,62].

The GDI is discussed above in detail. As a ratio of female HDI to male HDI, it measures average relative achievement in health, education, and wages [62,64].

The GII measures gender-based disadvantage using three dimensions: reproductive health, empowerment, and the labour market [62,67].

The PHDI adjusts the HDI for planetary pressures as a result of the Anthropocene that reflect intergenerational inequality. The specific adjustments include the following: (1) CO2 emissions produced per capita as a result of burning fossil fuels, gas flaring, and the manufacture of cement, and (2) material footprint per capita used in final demand. The latter is the sum of the material footprint for biomass, fossil fuels, metal ores, and non-metal ores [62,78].

Control variables are initially considered with guidance from methodological research discussing how the inclusion of controls may be decided upon [83,84]. Theory, the substantial expected relationship of controls to variables of interest and their reliable measurement, suggests the country’s population (Population) [84] (The World Bank, 2022), GDP (gross domestic product) (The World Bank, 2017) [85], the percentage of the national population that is female (% female population) (The World Bank, 2022) [86], and the Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI), called Poverty Index [82], could be included in the analysis [87]. The % female population was included because a country with a larger female population may be disposed to support women’s success. Some previous research is aligned with this view, finding that more women on boards of directors means that women’s issues will gain more attention [88]. MPI measures deprivation in health, education, and standard of living categories with ten weighted indicators. Poverty has been discussed in previous research as relevant for gender inequality, so it is an included control [66].

Also, a larger country by population or GDP may be perceived as having greater means to generate the support for women’s sports, by way of having more resources. Including GDP as a control would be a standard but not necessarily correct assumption often made in previous research, so this is why GDP was considered [43,89]. Methodological research has discussed these types of assumptions where controls are needlessly included because of habits in research and/or incorrect assumptions, including in the case of the relationship between a nation’s wealth and gender equality [43,89]. For example, some research has argued against the assumption that better economic conditions are related to gender equality, instead suggesting that gender inequality may be related to increased economic measures because the cost of women’s wages is lower [43]. Wealth measures, such as GDP, do not measure the distribution of wealth, including the gendered distribution of wealth [56]. Moreover, decisions about whether to include gender and the related econometric measures in economic analysis are socialized decisions that have trended toward ignoring them [43]. Thus, using theoretical reasoning from previous research on its own to make decisions about whether to include GDP or not could be arguable. Feminist research has argued against it [43,56].

In this research, correlation tables and a hierarchical regression approach are useful for supporting some of the latter types of decisions difficult to discern through theory. Regressions use controls depending on whether they were found significant in the first model of the hierarchical approach which only uses controls. In no case was GDP a relevant control variable, and this could also be expected as it is not highly correlated with either of the dependent variables or the independent variables. The latter outcome is interesting because so often in management research national wealth is automatically included and controlled for using GDP, but this outcome also supports the reasoning of this work. This work suggests that research needs to move away from a habit of including GDP to consider other more relevant factors, including the distribution of wealth, gender, and even the natural environment, as implied by the concept of sustainable development, a more holistic perspective. Researchers need to look further, as shown in this study.

3.2. Regression Analyses

A hierarchical regression analysis approach was used, beginning with potential control variables in a first model and then adding independent variables of interest one by one in subsequent models [90]. Collinearity among the independent variables prevented combining them in regressions. In consideration of using OLS with independent observations, one for each of 188 country teams, heteroscedasticity was tested for using a Breusch–Pagan test [91]. This test showed that heteroscedasticity was present in all models, so to correct for this, robust standard errors (Huber/White/sandwich estimator) were used [92]. Also, several models with different variables were tested along with graphical analysis showing the stability of the models such that omitted variable bias is unlikely [93,94].

4. Results

The descriptive statistics and pairwise correlations in Table 2 and Table 3 below provide some initial information about the dataset. The Soccer Rank and Total Points variables represent the standings of 188 countries in women’s soccer. The sample size is initially 188 observations except where some of the independent variables reduce the sample. For example, HDI is measured for 186 of the 188 countries in the sample, so the sample size is reduced, essentially inconsequentially, when including HDI as an independent variable. The pairwise correlations table, Table 3, shows that several variables are significantly correlated, so some of the hypothesized relationships are likely possible.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

Table 3.

Pairwise correlations.

The two following tables, Table 4 and Table 5, provide regression results. Table 4 uses Total Points as the dependent variable. In the first regression, Model 1 in Table 3, the potential control variables tested as significant were kept. Population and GDP variables were not significant, but the % Population Female and the Poverty Index were significant. This makes sense because more women and less poverty likely increases the potential pool of talent that can compete for a nation’s limited soccer team spaces [24]. GDP says nothing about wealth distribution, but a poverty index does. With fewer people struggling to survive on a daily basis, they may have more time to focus on their various interests and skills, including leisure and sports skills.

Table 4.

Regression models with Total Points as the dependent variable.

Table 5.

Regression models with Soccer Rank as the dependent variable.

For each regression using Total Points as the dependent variable in Table 4, the two control variables—% Population Female and the Poverty Index—were included unless found non-significant. Note that the collinearity of the HDI, GDI, GII, and PHDI variables prevents including them in the same regression.

In Model 2, where the HDI was tested, it makes sense that the Poverty Index would not be significant since they overlap in what they measure, both considering health, education, and standard of living-related variables. As expected, H1 is supported because the HDI is a large significant indicator of Total Points, together with % Population Female. So, more girls and women develop under better circumstances and can work toward their potential in higher HDI countries.

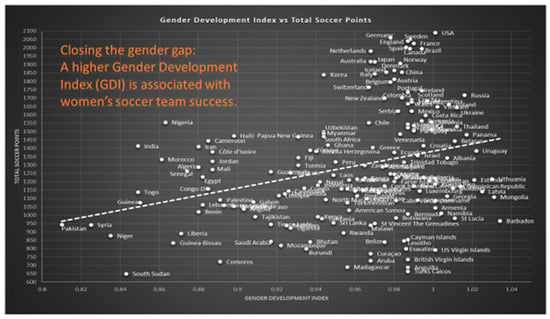

In Models 3 and 4, gender-oriented development measures are tested, including the Gender Development Index in Model 3 and the Gender Inequality Index in Model 4. The regression results help to show that the two measures are different from each other in respect of how the significant control variables change, the R-Squared, and ultimately, how they affect the Total Points. Using the Gender Development Index (GDI), the two control variables are not relevant, but the R-Squared drops compared to the other models. The GDI is significant in Model 3, suggesting that gender issues matter for women’s soccer success, a consequence that future research should consider. Rather than defaulting to the HDI as an improved measure for ranking countries by wealth (often used instead of GDP because GDP is too narrow a measure), studies could consider the GDI. Higher gender development is consequential for developing winning women’s soccer teams, but it may have many other consequences to be discovered in future research.

The GII is a different measure, as used in Model 4, such that a higher measure means higher gender inequality. Model 4 shows an improved R-squared no matter the slightly smaller sample size of 173 compared to 177 for Model 3 with the GDI. As compared to Model 1 with only controls, Model 4 improves the R-squared no matter the decreased sample size of 173 down from 185. Therefore, the GII adds information that decreased gender inequality explains the success of women’s soccer teams.

Overall, either GDI or GII could be useful in future research depending on the preference for matching to a context, where GDI is a positive measure of gender equality achievement and GII is a negative measure of inequality or disadvantage. These results suggest that positive investments made to improve gender equality pay off, and it is not just decreasing inequality but also boosting equality that makes a difference.

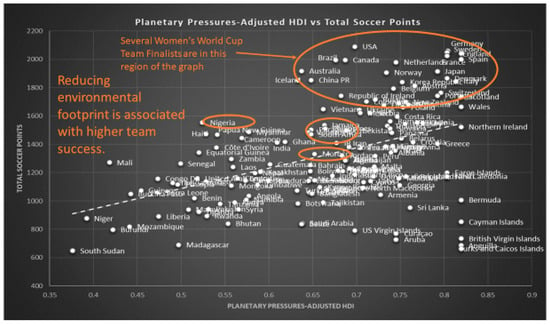

In Model 5, testing the Planetary pressures-adjusted HDI shows how important other unexpected factors such as the natural environment affect soccer teams’ success. The PHDI model has a relatively high R-Squared in line with other models. This PHDI measure which adjusts the HDI to include a country’s carbon dioxide emissions per capita produced by human activities and the material footprint per capita has an effect on women’s soccer team outcomes. This outcome shows how multiple factors represented by the UN SDGs are related to each other.

The results show that researchers should consider factors that may be more difficult to directly rationalize based on norms of thinking today. Our norms tend to put issues into silos, such as the separation of the UN SDGs, ignoring the wicked interrelatedness of the real world [2]. In this case, we must remember that humans are part of the earth, not separate from it [95]. Without considering a broader set of factors, this may potentially lead to limited research investigations that are too narrow for solving wicked problems. See Figure 2 and Figure 3 for graphs of the GDI and PHDI relationships with Total Points.

Figure 2.

Graph of Gender Development Index versus Total Points.

Figure 3.

Graph of planetary pressures-adjusted HDI versus Total Points.

The next set of regression models in Table 5 using Soccer Rank as the dependent variable mirror the regression models in Table 4. Note that Soccer Rank works in the opposite direction to Total Points, where higher Total Points translates to a higher ranking, but the soccer ranking is higher with a smaller number. The top team is Number 1, the second from the top is Number 2, and so on. This means that the positive and negative signs on the coefficients must be interpreted opposite to the ones in Table 4. Overall, the results in Table 5 are similar to those in Table 4 with a few differences that are discussed.

One difference found in Model 1 of Table 5 with controls only is that Population becomes an additional significant control variable, albeit with a very small effect size that is interpreted as zero. Based on the similar results in Table 5 using Soccer Rank at the dependent variable, the same observations as made above using Total Points hold.

5. Discussion

The evidence from the analysis supports the hypotheses showing that the Gender Development Index (GDI) and the Planetary pressures-adjusted HDI (PHDI) provide more information about what supports Women’s World Cup soccer team wins. This means that a composite measure, such as the GDI, comparing female to male conditions, including relative health at birth, years of education, and command over economic resources, should be considered in various areas of social science research, such as sports, business, and economics, that regularly ignore gender differences as a first assumption.

Moreover, the PHDI is a relevant composite environmental variable also representing intergenerational equity that could be considered in the same types of social science research. Sports, business, and economics do not regularly consider planetary conditions. The findings of this research suggest that PHDI may also be related to gender outcomes. Remembering the wickedness of the real world in research is important to understand better how we generate success, as demonstrated for women in this study. As an extension of this research, future research could examine whether women’s successes may be supported by more sustainable conditions in other male-dominated sports and business arenas.

Also, in accordance with Literature and empirical evidence, controls routinely used in research, such as GDP, are not relevant [96]. Past research has discussed the problems with GDP at length, for example, in the context of well-being, but little work has also included gender, recognizing that the SDGs are interlinked [96]. To improve well-being as related to sustainable development, gender matters. GDP has little direct relationship with differential gender conditions, especially noting it does not include the bulk of unpaid work performed by women [97].

Clearly, improving women’s health, education, and economic power delivers real outcomes for women in international soccer. Also, reducing climate change and other types of pollution that damage the environment is consequential for women’s soccer success. These variables in combination may be consequential for women’s successes in other sports and well beyond.

This international-level research provides general direction implying that sustainable conditions are likely beneficial for women’s outcomes. It also demonstrated that other national-level variables incorporating gender and/or sustainability should be considered in future empirical research. Overall, this analysis shows that sustainable development improvements are linked to another aspect of sustainability, gender equality.

Future research could examine more interlinkages among high level UN SDG issues to demonstrate the challenges we face, recognizing that interconnected issues make these wicked UN SDG problems even more wicked. Research could also investigate potential gender-supportive policies, implying a more detailed level of data collection examining issues such as increasing available sports infrastructure and coaching for women. Moreover, case study research could search for culturally supportive variables that may influence women’s equality and sports success. Furthermore, future empirical analyses could use panel data over long time periods to look at whether and how these relative UN SDG linkages change over time. This research aimed to take a high-level international perspective, and in doing so, a limitation of the models of this research could be omitted variables bias since much detailed differential information about countries’ conditions for women around the world is not available, and it would be difficult to pinpoint which data would be most relevant [93].

Some countries, such as Sweden, England, Spain, and Australia, in the top ranks of women’s soccer have made investments and implemented policies in women and girls beyond women’s sports, and it shows [98]. Scandinavian countries have stood out. For example, Sweden devised a National Gender Equality Policy. This policy is wide ranging, including a clear message that men’s violence against women is intolerable and addressing unpaid work in the home [99].

Other notable countries at the top of the World Cup list, such as England, are directly addressing the pay gap, requiring employers with 250 employees or more to report [65,100]. Gender inequality is such a wicked problem that it permeates many aspects of women’s lives, including reproductive rights, which are unfortunately also connected to women’s economic power [62]. Spain noticeably ensures access to sexual and reproductive rights [101]. Spain’s “The Equality Law” institutionalizes across public and private organizations, for example, through paternity leave, fairer political representation, and equality plans [102]. Australia also has a National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality and a Women’s Economic Equality Taskforce [103]. Literature has recommended many of the same policies these countries have embarked upon [104]. Correspondingly, these countries also rank high in sustainable development [105].

A sports business context was useful for its particularly well-known patriarchal conditions, so if progress is being made in this realm, we might consider how these learnings could transfer to a wide range of industries and test related research in those other contexts [12]. Previous research has found that gender inequalities in sports can be reduced through several key measures. First, ensuring that female athletes receive the same financial rewards and sponsorship deals as their male counterparts can help bridge the gender gap [106]. This has been implemented in sports like tennis, where major tournaments offer equal prize money [107].

Also, promoting and broadcasting women’s sports on mainstream platforms can elevate the visibility and recognition of female athletes [108]. More media attention can lead to higher sponsorship opportunities and a broader fan base [106].

In addition, women must have equal access to high-quality training programs, coaching staff, and sports facilities, all crucial for levelling the playing field [109,110]. This includes investment in female sports academies and development programs. Promoting women to leadership roles such as coaches, referees, administrators, and sports executives can also help to ensure that decision-making processes are more inclusive and representative of both genders [111]. Policymakers could help to support these types of initiatives by mandating equitable financial support for women’s and men’s sports programs, including salaries, facilities, and development initiatives. Establishing quotas for women in coaching, officiating, and executive roles could help to dismantle systemic barriers. Anti-discrimination measures could include strengthening policies against sexism, harassment, and unequal treatment in sports organizations. Also, policies should enforce fair coverage of women’s sports to boost visibility and commercial opportunities. Challenging stereotypes about women’s capabilities in sports and promoting positive role models can inspire young girls to participate in sports without fear of stigma or discrimination [112].

At the macro level, national and international sports organizations can implement and enforce policies aimed at ensuring gender equity in participation, funding, and representation at all levels of sport [112]. Creating safe and supportive environments by implementing strict policies against gender-based violence, harassment, and discrimination may also help [113]. Athletes must feel safe and respected in their sport [114].

Finally, encouraging girls’ participation in sports from a young age, providing opportunities at schools, and creating programs that support long-term engagement in sports can help reduce gender inequalities [3,115]. For example, expanded access to sports for girls through school programs and community leagues could contribute toward ensuring inclusivity, fairness, and long-term growth in sports. Related Literature suggests that women in visible leadership positions, such as at the top of sports bodies, can actively combat stereotypes while acting as role models within local communities where they may interact directly with and encourage aspiring girls and young women [3,116,117]. By addressing these factors, sports can become a more inclusive and equitable environment for all genders.

Overall, dealing with wicked problems such as gender inequality is not easy, partly because of siloed perspectives fostered early in educational systems that separate subjects as if they are not interlinked [118]. Big, real-world problems require combining mindsets to see through multidimensional complexity and develop solutions that are also multifaceted and complex, as per wicked problems Literature [2,35,36]. Recent research has started to explore how to develop and implement pragmatic sustainability solutions that require the combination of diverse expertise [119]. For example, in the context of urban sustainability where cities are facing climate and environmental risks, more resilient infrastructure is designed through interdisciplinary collaboration [120]. Literature is also recognizing that interdisciplinary work needs a workforce that can think and work collaboratively through the complexity, so education has to adapt accordingly [121,122].

6. Conclusions

The FIFA Women’s World Cup winning teams and other progress in high-level sports, such as the new Professional Women’s Hockey League (PWHL) in Canada and the US, with three teams each founded in August 2023, stand out as markers to watch for continuing women’s progress in certain countries. When this demonstrable progress is taken together with the research findings here, an implication is that the linkages between sustainability and women’s success may be noted by countries lagging on UN SDG 5. When noticing the worldwide celebrations of these special winning countries’ teams, other nations may make the connection that investing in sustainability for women, including the environment, pays off. Neglecting approximately 50% of a population and losing the beneficial outcomes of all that unrealized talent can only hold a country back from being internationally competitive, not just in sports.

This empirical work has made several contributions by discussing and providing evidence for the aforementioned perspectives to holistically address UN SDG 5 through sustainability. Moreover, it tested development indices including the HDI, GDI, GII, and PHDI to show that their components are consequential for policy innovations that may improve the condition of women. The findings also suggest that these development indices should be considered more regularly in future research, such as in sports, economics, and business studies. The possible choice of these measures needs to be normalized in research so that research avoids inadvertently furthering patriarchy and, instead, integrates sustainability into research. This would have consequences across many realms as research influences practice.

Overall, this research adds some evidence toward our greater understanding of the interconnectedness of the UN SDGs while building on researchers’ awareness of the complications that wicked problems represent for research. The implications for research, after showing that women’s success in soccer is affected by sustainability factors, are vast. This not only means that investment in sustainability is likely important for women, but also that future research may uncover many more critical interlinkages among the UN SDGs. Future research may also search for the limitations of these UN SDG interlinkages. Are there boundaries to these interlinkages, and where are they?

Moreover, this research adds to the calls for future research to go beyond choosing controls and factors of interest because of the normalization of routinized research traditions. While it is often hard for academic work to step outside of traditional boundaries, for the sake of better science and the many more potentially positive consequences resulting from the application of improved science, this is necessary. The results of this work encourage more holistic and accurate future research toward inclusion of what might at first be unexpected sustainability-related factors, including gender and environmental factors. Future research will also need to contend with where to draw the line on these potential choices without blindly and incorrectly turning to the excuse of tradition as a crutch.

In conclusion, unfortunately today, we can only imagine the heights women could reach if the gender gap did not exist. Improved interdisciplinary sustainability research in business, sports, and beyond that consistently considers gender can help us to monitor our progress and develop innovative solutions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.d.L.; Methodology, D.d.L.; Validation, W.L.F.; Formal analysis, D.d.L.; Writing—original draft, D.d.L.; Writing—review & editing, W.L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank three anonymous reviewers for their detailed and highly constructive comments that helped to substantially improve this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Eden, L.; Wagstaff, M.F. Evidence-based policymaking and the wicked problem of SDG 5 Gender Equality. J. Int. Bus. Policy 2021, 4, 28–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCune, V.; Tauritz, R.; Boyd, S.; Cross, A.; Higgins, P.; Scoles, J. Teaching wicked problems in higher education: Ways of thinking and practising. Teach. High. Educ. 2023, 28, 1518–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozhabri, K.; Sobry, C.; Ramzaninejad, R. Sport for Gender Equality and Empowerment. In Sport for Sustainable Development: Historical and Theoretical Approaches; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Saavedra, M. Dilemmas and opportunities in gender and sport-in-development. In Sport and International Development; Levermore, R., Beacom, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 124–155. [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, D. FIFA Women’s World Cup Successes Reflect Gender Gap Differences Between Countries. The Conversation, 21 August 2023. Available online: https://theconversation.com/fifa-womens-world-cup-successes-reflect-gender-gap-differences-between-countries-211715 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Hylton, T. FIFA Women’s World Cup: Gender Equity in Sports Remains an Issue Despite the Major Strides Being Made. The Conversation, 18 July 2023. Available online: https://theconversation.com/fifa-womens-world-cup-gender-equity-in-sports-remains-an-issue-despite-the-major-strides-being-made-209778 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kent, S.; Miller, D.Y. Beneath the Surface of Women’s World Cup Marketing. Business of Fashion, 18 August 2023. Available online: https://www.businessoffashion.com/articles/marketing-pr/nike-adidas-womens-world-cup-football-equality-workers-rights-marketing/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Worden, M. Women’s World Cup Shows Equality Still Has A Long Way To Go. Forbes, 25 July 2023. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/07/25/womens-world-cup-shows-equality-still-has-long-way-go (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Watson, F. England vs Spain Controversy Saw Chief Banned from Football for Three Years. Express, 27 July 2025. Available online: https://www.express.co.uk/sport/football/2086224/England-Spain-Jenni-Hermoso-Luis-Rubiales-kiss (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Thomson Reuters. FIFA Suspends Spain Soccer Chief over World Cup Kiss That Player Says Wasn’t Consensual. CBC Sports, 26 Aug 2023. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/sports/spain-soccer-hermoso-legal-action-1.6948640 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- United Nations. The 17 Goals. 2023. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Evans, A.B.; Pfister, G.U. Women in sports leadership: A systematic narrative review. Int. Rev. Sociol. Sport 2021, 56, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galea, N.; Chappell, L. Male-dominated workplaces and the power of masculine privilege: A comparison of the Australian political and construction sectors. Gend. Work. Organ. 2022, 29, 1692–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmat, F.; Lim, W.M.; Moyeen, A.; Voola, R.; Gupta, G. Convergence of business, innovation, and sustainability at the tipping point of the sustainable development goals. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 167, 114170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damanpour, F. Organizational complexity and innovation: Developing and testing multiple contingency models. Manag. Sci. 1996, 42, 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Riaz, H.; Liedong, T.A.; Rajwani, T. The impact of TMT gender diversity on corporate environmental strategy in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 141, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrowicz, J.; Terjesen, S.; Mazurek, J. All on board? New evidence on board gender diversity from a large panel of European firms. Eur. Manag. J. 2020, 38, 634–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosheen, M.; Iqbal, J.; Ahmad, S. Economic empowerment of women through climate change mitigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resurrección, B.P. Persistent women and environment linkages in climate change and sustainable development agendas. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2013, 40, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, M.; Wang, F.; Usman, M.; Gull, A.A.; Zaman, Q.U. Female CEOs and green innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, I.M.; Aibar-Guzmán, C.; Núnez-Torrado, M.; Aibar-Guzmán, B. Women leaders and female same-sex groups: The same 2030 Agenda objectives along different roads. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 157, 113582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, P.N.; Huffman, M.L. Working for the woman? Female managers and the gender wage gap. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2007, 72, 681–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P.B.; Fletcher, D.; Sarkar, M. Understanding team resilience in the world’s best athletes: A case study of a rugby union World Cup winning team. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2015, 16, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bosscher, V.; De Knop, P.; Van Bottenburg, M.; Shibli, S. A conceptual framework for analysing sports policy factors leading to international sporting success. Eur. Sport Manag. Q. 2006, 6, 185–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, S.; Amis, J. Image and investment: Sponsorship and women’s sport. J. Sport Manag. 2001, 15, 219–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, C.G.; Shaw, S.M.; Havitz, M.E. Men’s and women’s involvement in sports: An examination of the gendered aspects of leisure involvement. Leis. Sci. 2000, 22, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel, H.; Semyonov, M. Family policies, wage structures, and gender gaps: Sources of earnings inequality in 20 countries. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2005, 70, 949–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brick, C.; Schneider, D.; Harknett, K. The Gender Wage Gap, Between-Firm Inequality, and Devaluation: Testing a New Hypothesis in the Service Sector. Work. Occup. 2023, 50, 539–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penner, A.M.; Petersen, T.; Hermansen, A.S.; Rainey, A.; Boza, I.; Elvira, M.M.; Godechot, O.; Hällsten, M.; Henriksen, L.F.; Hou, F.; et al. Within-job gender pay inequality in 15 countries. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2023, 7, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semali, L.M.; Shakespeare, E.S. Rethinking Mindscapes and Symbols of Patriarchy in the Workforce to Explain Gendered Privileges and Rewards. Int. Educ. Stud. 2014, 7, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, E.C.; Cunningham, F.J.; Hemingway, S.L.; Tschida, S.L.; Jacquin, K.M. Indicators of gender inequality and violence against women predict number of reported human trafficking legal cases across countries. J. Hum. Traffick. 2023, 9, 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullen, Z.; Perez-Truglia, R. The old boys’ club: Schmoozing and the gender gap. Am. Econ. Rev. 2023, 113, 1703–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreft, A.K. “This patriarchal, machista and unequal culture of ours”: Obstacles to confronting conflict-related sexual violence. Soc. Politics Int. Stud. Gend. State Soc. 2023, 30, 654–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghadam, V.M. Gender regimes, polities, and the world-system: Comparing Iran and Tunisia. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2023, 98, 102721. [Google Scholar]

- Rittel, H.; Webber, M. Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning. Policy Sci. 1973, 4, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tulder, R.; Rodrigues, S.B.; Mirza, H.; Sexsmith, K. The UN’s sustainable development goals: Can multinational enterprises lead the decade of action? J. Int. Bus. Policy 2021, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrary, M. The French approach to promoting gender diversity in corporate governance. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 42, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, M.A. Sports and male domination: The female athlete as contested ideological terrain. Sociol. Sport J. 1988, 5, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.A.; Bopp, T. The underrepresentation of women in the male-dominated sport workplace: Perspectives of female coaches. J. Workplace Rights 2011, 15, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, R.S.; Whitaker, K.G.; Smith, N.J.W.; Sablove, A. Changing the rules of the game: Reflections toward a feminist analysis of sport. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 1987, 10, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carty, V. Textual portrayals of female athletes: Liberation or nuanced forms of patriarchy? Front. J. Women Stud. 2005, 26, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovits, A.S.; Markovits, S.L. Women’s Soccer in the United States: Yet Another American ‘Exceptionalism’. In Soccer, Women, Sexual Liberation; Routledge: London, UK, 2004; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Seguino, S. Gender inequality and economic growth: A cross-country analysis. World Dev. 2000, 28, 1211–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrijevic, M.; Crespo Cuaresma, J.; Lissner, T.; Thomas, A.; Schleussner, C.F. Overcoming gender inequality for climate resilient development. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernando, G.D.; Schneible, R.A., Jr.; Zhang, W. Institutional ownership and women in the top management team. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 170, 114279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoppers, A.; de Haan, D.; Norman, L.; LaVoi, N. Elite women coaches negotiating and resisting power in football. Gend. Work. Organ. 2022, 29, 880–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koca, C.; Arslan, B.; Aşçı, F.H. Attitudes towards women’s work roles and women managers in a sports organization: The case of Turkey. Gend. Work. Organ. 2011, 18, 592–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Jimenez, R.; Hernández-Ortiz, M.J.; Cabrera Fernández, A.I. Gender diversity influence on board effectiveness and business performance. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2020, 20, 307–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasey, K.J.; Sarkar, M.; Wagstaff, C.R.; Johnston, J. Defining and characterizing organizational resilience in elite sport. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2021, 52, 101834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, L.J. Underrepresentation of women in sport leadership: A review of research. Sport Manag. Rev. 2015, 18, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.; Hanlon, C.; Apostolopoulos, V. Continuum of care to advance women as leaders in male-dominated industries. Gend. Work. Organ. 2024, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, W.; Hanlon, C.; Apostolopoulos, V. Women as leaders in male-dominated sectors: A bifocal analysis of gendered organizational practices. Gend. Work. Organ. 2023, 30, 1867–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beloskar, V.D.; Haldar, A.; Gupta, A. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A bibliometric review of the literature on SDG 5 through the management lens. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 172, 114442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brundtland, G.H. What is Sustainable Development: Our Common Future. 1987. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Leal Filho, W.; Kovaleva, M.; Tsani, S.; Țîrcă, D.M.; Shiel, C.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Nicolau, M.; Sima, M.; Fritzen, B.; Salvia, A.L.; et al. Promoting gender equality across the sustainable development goals. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2023, 25, 14177–14198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berik, G. To measure and to narrate: Paths toward a sustainable future. Fem. Econ. 2018, 24, 136–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kossek, E.E.; Buzzanell, P.M. Women’s career equality and leadership in organizations: Creating an evidence-based positive change. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2018, 57, 813–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannetti, B.F.; Agostinho, F.; Almeida, C.M.; Huisingh, D. A review of limitations of GDP and alternative indices to monitor human wellbeing and to manage eco-system functionality. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 87, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, M.; Harttgen, K.; Klasen, S.; Misselhorn, M. A human development index by income groups. World Dev. 2008, 36, 2527–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Patz, J.A. Emerging threats to human health from global environmental change. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2009, 34, 223–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. 2021/22. Human Development Index. HDI. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human-development-index#/indicies/HDI (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- United Nations Development Programme. 2021/22. Human Development Report. Technical Notes. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/2021-22_HDR/hdr2021-22_technical_notes.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Carlsen, L. Gender inequality and development. Sustain. Sci. 2020, 15, 759–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. 2021/22. Gender Development Index. GDI. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/gender-development-index#/indicies/GDI (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- García, C.J.; Herrero, B.; Vila, L.E. The gender pay gap at the top floor: A multilevel analysis of Spanish listed companies. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 43, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azcona, G.; Bhatt, A. Inequality, gender, and sustainable development: Measuring feminist progress. Gend. Dev. 2020, 28, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. 2021/22. Gender Inequality Index. GII. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/thematic-composite-indices/gender-inequality-index#/indicies/GII (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Permanyer, I. A critical assessment of the UNDP’s gender inequality index. Fem. Econ. 2013, 19, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbash, K.S.; Pasichnyk, N.O.; Rizhniak, R.Y. Adaptation of the UN’s gender inequality index to Ukraine’s regions. Reg. Stat. 2019, 9, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, E.; Sabermahani, A. Gender inequality index appropriateness for measuring inequality. J. Evid.-Inf. Soc. Work 2017, 14, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.I.; Kim, G. Labor force participation and secondary education of gender inequality index (GII) associated with healthy life expectancy (HLE) at birth. Int. J. Equity Health 2014, 13, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. The triple bottom line. Environ. Manag. Read. Cases 1997, 2, 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J.; Rowlands, I.H. Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. Altern. J. 1999, 25, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivkovic, S. Systemic innovation labs: A lab for wicked problems. Soc. Enterp. J. 2018, 14, 348–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R.; Wernham, A. Integrating human health into environmental impact assessment: An unrealized opportunity for environmental health and justice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2008, 116, 991–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocheleau, D.; Thomas-Slayter, B.; Wangari, E. Gender and environment: A feminist political ecology perspective. In Feminist Political Ecology; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhu, D. Incorporating “relative” ecological impacts into human development evaluation: Planetary Boundaries–adjusted HDI. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 137, 108786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. 2021/22. Planetary Pressures-Adjusted HDI. PHDI. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/planetary-pressures-adjusted-human-development-index#/indicies/PHDI (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Abid, Z.; Abid, M.; Zafar, Q.; Mehmood, S. Detrimental effects of climate change on women. Earth Syst. Environ. 2018, 2, 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denton, F. Climate change vulnerability, impacts, and adaptation: Why does gender matter? Gend. Dev. 2002, 10, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedin, M.A.; Habiba, U.; Shaw, R. Gender and climate change: Impacts and coping mechanisms of women and special vulnerable groups. In Climate Change Adaptation Actions in Bangladesh; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 165–184. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme. Multidimensional Poverty Index. MPI. 2021/22. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/content/2022-global-multidimensional-poverty-index-mpi#/indicies/MPI (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- FIFA. Women’s Ranking, 9 June 2023. Available online: https://www.fifa.com/fifa-world-ranking/women?dateId=ranking_20230609 (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. Population [Data File]. 2022. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. GDP, PPP [Data File]. 2017. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.PP.KD (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- The World Bank. World Development Indicators. Population, Female [Data File]. 2022. Available online: http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL.FE.ZS (accessed on 2 July 2023).

- Bernerth, J.B.; Aguinis, H. A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Pers. Psychol. 2016, 69, 229–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, R.J. Women on corporate boards of directors: A needed resource. J. Bus. Ethics 1997, 16, 909–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P.E.; Brannick, M.T. Methodological urban legends: The misuse of statistical control variables. Organ. Res. Methods 2011, 14, 287–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, P.F. Hierarchical regression analysis in structural equation modeling. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cribari-Neto, F.; Zarkos, S.G. Bootstrap methods for heteroskedastic regression models: Evidence on estimation and testing. Econom. Rev. 1999, 18, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F.; Cai, L. Using heteroskedasticity-consistent standard error estimators in OLS regression: An introduction and software implementation. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 709–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, D. From association to causation via regression. Adv. Appl. Math. 1997, 18, 59–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, C.H.; Patil, S.R. Identification and review of sensitivity analysis methods. Risk Anal. 2002, 22, 553–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallenhorst, N. A Critical Education: We Are Not Separate from the Earth–We are the Earth. In A Critical Theory for the Anthropocene; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 361–382. [Google Scholar]

- Munda, G. Beyond GDP: An overview of measurement issues in redefining ‘wealth’. J. Econ. Surv. 2013, 29, 403–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jany-Catrice, F.; Méda, D. Women and wealth: Beyond GDP. Trav. Genre Et Sociétés 2011, 26, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum. UEFA Women’s Euro 2025 Highlights Why We Must Invest in Gender Parity to Redefine Women’s Sports, 2 July 2025. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/07/invest-in-gender-parity-to-redefine-womens-sports/ (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Europa. Sweden. Gender Mainstreaming, December 2022. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/countries/sweden (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Gov.uk. Statutory Guidance–Who Needs to Report, 15 March 2023. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/gender-pay-gap-reporting-guidance-for-employers/who-needs-to-report (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. Spain: UN Experts Hail New Feminist Legislation. 21 February 2023. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2023/02/spain-un-experts-hail-new-feminist-legislation (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Europa. Spain. Gender Mainstreaming, December 2022. Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-mainstreaming/countries/spain?language_content_entity=en (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Australian Government Office for Women. 2024. National Strategy to Achieve Gender Equality. Available online: https://www.pmc.gov.au/office-women/national-strategy-achieve-gender-equality (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Tzannatos, Z. Women and labor market changes in the global economy: Growth helps, inequalities hurt and public policy matters. World Dev. 1999, 27, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Development Report Rankings. 2024. Available online: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/rankings (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Mogaji, E.; Badejo, F.A.; Charles, S.; Millisits, J. Financial well-being of sportswomen. Int. J. Sport Policy Politics 2021, 13, 299–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scovel, S. ‘Complaining’,‘campaigning’, and everything in between: Media coverage of pay equity in women’s tennis in 1973 and 2007. Sport Soc. 2024, 27, 1357–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooky, C.; Council, L.D.; Mears, M.A.; Messner, M.A. One and done: The long eclipse of women’s televised sports, 1989–2019. Commun. Sport 2021, 9, 347–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, L.A. Altering the narrative of champions: Recognition, excellence, fairness, and inclusion. Sport Ethics Philos. 2020, 14, 496–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, A. Women in sport. Sport Ethics Philos. 2020, 14, 415–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pape, M. Gender segregation and trajectories of organizational change: The underrepresentation of women in sports leadership. Gend. Soc. 2020, 34, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebel, K.; Mumcu, C.; Pegoraro, A.; LaVoi, N.M.; Lough, N.; Antunovic, D. Re-thinking women’s sport research: Looking in the mirror and reflecting forward. Front. Sports Act. Living 2021, 3, 746441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasting, K.; Brackenridge, C.; Walseth, K. Women athletes’ personal responses to sexual harassment in sport. J. Appl. Sport Psychol. 2007, 19, 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, P.; Sun, L.; Shi, S.S.; Ahmed Laar, R.; Lu, Y. Influencing factors related to female sports participation under the implementation of Chinese government interventions: An analysis based on the China Family Panel Studies. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 875373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Svender, J.; Larsson, H.; Redelius, K. Promoting girls’ participation in sports: Discursive constructions of girls in a sports initiative. Sport Educ. Soc. 2012, 17, 463–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Be, M. The Working Elements of Moving the Goal Posts: Football, Peer Education and Leadership in Kenyan Girls. Unpublished Master’s Thesis, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meier, M. The value of female sporting role models. Sport Soc. 2015, 18, 968–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, E.; Volet, S.; Baudains, C.; Mansfield, C. Education for sustainability at a Montessori primary school: From silos to systems thinking. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2012, 28, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Vaverková, M.D.; Polak, J.; Kurcjusz, M.; Jena, M.K.; Murali, A.P.; Nair, S.S.; Aktaş, H.; Hadinata, M.E.; Ghezelayagh, P.; Andik, S.D.S.; et al. Enhancing sustainable development through interdisciplinary collaboration: Insights from diverse fields. Sustain. Dev. 2025, 33, 3427–3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Willis, S.; Dallmann, A.; Cai, H.; Hu, L.; Zou, L.; Zhai, W.; He, C.; Alberston, J.; Zhao, X.; et al. Urban Climate Adaptation and REsilience (U-CARE) in Texas: Insights from Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2025, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Adamo, I.; Ozturk, I.; Passarelli, F.; Salvati, C. Economic Analysis, Innovative Educational Models and Pragmatic Sustainability: The Case Study of a Photovoltaic System on a Public Building. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2025, 15, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odo, J.O.; Val-Eke, I.F. Interdisciplinarity In Sustainability Practice: Rethinking Accounting Education And Implications With Engagement In Practice A Critical Review. J. Interdiscip. Res. Account. Financ. 2025, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).