The Health of the Governance System for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef 2050 Plan: A First Benchmark

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

- Literature review of governance theory to identify concepts, principles and frameworks for evaluating governance systems health;

- Twenty-one interviews conducted with actors from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority (the Reef Authority), the Australian and State governments, GBR industries and communities and scientific experts. A further seven interviews were undertaken with members of the Traditional Owner Steering Group for the Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Implementation Plan. These interviews were conducted online (using Zoom) and in person, transcribed and coded into themes;

- Two in-person workshops in different Queensland locations with sixteen diverse GBR actors and Traditional Owners to provide deeper perspectives on governance health and to generate feedback on an emerging evaluation framework. A third online workshop was held to accommodate participants who could not attend in person. A further six deeper conversations were held with members of the Traditional Owner Steering Group for the Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Implementation Plan to assist with framework development.

- The complex Reef 2050 Plan governance system was mapped using igraph and visNetwork software within the programme ‘R’, to define the scope of the policy and planning arrangements auspiced by the Reef 2050 Plan and identify connections between GBR actors and instruments (e.g., funding programmes, legislative actions and formal partnerships); and

- The research team developed and applied a clear a theory of change, drawing on Funnell and Rogers [38], Reinholz and Andrews [39] and Thornton, et al. [40]. This was used in concert with multiple lines of evidence to establish causal links and sequences of action impacting on governance outcomes in the Reef 2050 Plan system.

- A thematic analysis of academic and grey literature (reports, evaluations) that provided perspectives and data points on aspects of attribute health;

- In depth qualitative analysis of case materials leading to a detailed governance case study for of each attribute;

- Key actor interviews (n = 20) in which participants used a Likert scale (based on Table 2) to rate each attribute and provided narratives to support their scores; and

- A series of three workshops with GBR governance experts in multiple Queensland locations to consider and respond to a consolidated evaluation (interviews + case studies + literature) and discuss findings of the benchmark. Separate conversations were held with members of the Traditional Owner Steering Group for the Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Implementation Plan

3. Results

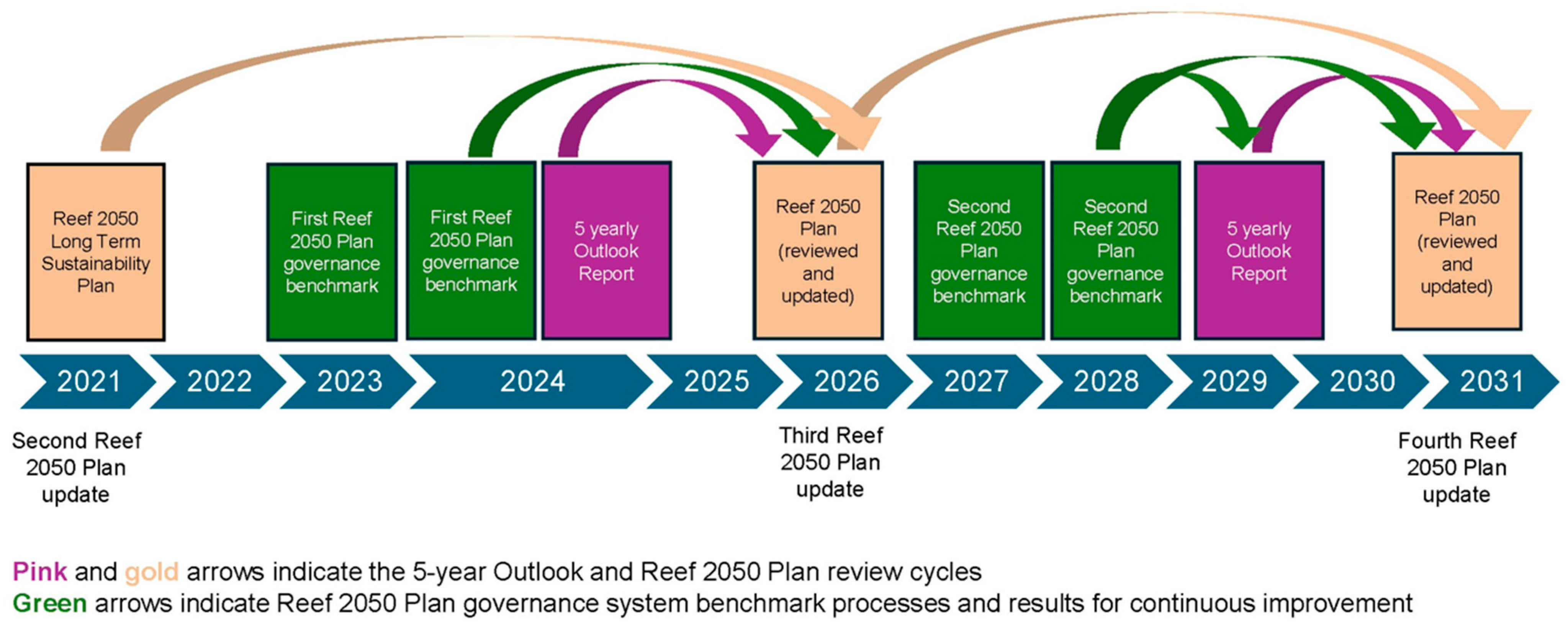

3.1. The Reef 2050 Plan and Adaptive Governance Needs

3.2. A First Benchmark of GBR Governance Health

4. Discussion

- Global Leadership in Emissions Reduction and Climate Adaptation. A significant area of new national policy strength of importance to the Reef 2050 Plan governance system is demonstrated through Australia now playing an increasingly strong global leadership role in emissions reduction and climate adaptation. This is a feature of both state and federal policy efforts nationally in relation to making progress toward a greater decarbonisation of the economy. If Australia was not playing a significant role in climate change mitigation and adaptation on a global scale, then the GBR governance system could have increasingly become viewed as not being robust in the global context. A growing national policy focus on emissions reduction signals positive change. The GBR’s status as a World Heritage property of Outstanding Universal Value also galvanises the national appetite for the development of strong alliances between the tourism industry, public sector and national and international organisations that lead to the development of climate stewardship programmes, all built on shared values of protecting the GBR [72,73,74];

- The Emerging Reef 2050 Planning Process. Supported by both Commonwealth and state governments, the Reef 2050 Planning system itself provides the overarching mechanism for the articulation of a collective vision for the GBR; an integrated legal framework; and aligned, multi-scale and prioritised strategies that are evaluated and reviewed periodically. Thus, the Reef 2050 Planning process should be maintained and enhanced into the future;

- Crisis Monitoring and Response Systems. There is evidence for the stronger emergence of more adaptive and real-time monitoring and response systems for specific forms of crisis and disaster response, including bleaching events, and the application of strong risk-oriented approaches in a wide range of GBR-related activities. Adaptive approaches are developing across the GBR through the emerging Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP), which globally leads the development of new coral-reef restoration and adaptation solutions [75,76]. As adaptive governance approaches are crucial to respond to emerging climate crises, the establishment of the RRAP represents an innovative and holistic focus of GBR management toward long-term outcomes [77,78];

- A Durable Focus on Fisheries, Marine Park Management and Compliance. Queensland has an established fisheries planning and management system. Similarly, GBR management agencies have a sound track record of innovation and success in GBR management. Nevertheless, ongoing effort is still needed to make sure that strong industry-based and co-managed approaches enhance these arrangements to enable continuous improvement;

- Progress on Integrated Monitoring and Reporting. Until the Reef 2050 Plan was established and implemented, there was no integrated approach to monitoring the social, cultural, economic and ecological dimensions of the GBR system, although some programmes, such as the Long-Term Monitoring Program, have been well established for decades. While development of the RIMReP framework has been slow, progress in this direction is progressing and is much needed to ensure the health of the Reef 2050 Plan governance system. As argued by Dale et al. [79], while the development of GBR-wide monitoring frameworks is progressing, less effort has been made at the regional levels, weakening the ability of regions to influence GBR-wide policy making [80]. In alignment with the literature highlighting improved GBR management through zoning and land-use regulations, our findings also identified significant progress in the governance and management of the marine park itself [81,82,83].

- Genuine power sharing with key GBR actors. While there is an emerging appetite for improvement, there remains a lack of genuine power sharing with Traditional Owners, local government and industry [84,85] in the GBR. Healthy governance systems, however, require the inclusive participation of many diverse actors to foster a genuine sense of co-management of the GBR. It is therefore a priority for the Queensland and Australian governments to rebuild subsidiary systems, trust and stronger partnerships, not just with Traditional Owners but also with the farming, agricultural and fishing sectors and local governments across the GBR catchment;

- Improved trilateral relations between federal, state and local governments. Poor coordination of efforts across different governance levels has also been a long-standing issue for the GBR, particularly at the lower scales [86,87]. In this regard, our results have highlighted continued fragmentation in programme implementation and the weak application of trilateral approaches (combining the efforts of federal, state and local governments). This is particularly the case in relation to land-based action and community-based education. An opportunity for reform these approaches lies in prioritising the strengthening of more trilateral approaches to GBR governance, particularly with more support being provided to local governments across the GBR [88]. More trilateral approaches would facilitate improved co-design of delivery effort, including at regional, catchment, local, traditional owner and farm scales;

- Building a culture of subsidiarity. It is a priority for the GBR to foster a stronger culture of subsidiarity to improve cohesive implementation of multi-scale strategies, which are currently problematic due to fragmented and short-term funding, and limited integration of place-based strategies [89]. If subsidiarity issues are not addressed, they will impact on the strength of those key organisations involved in catchment scale action, including regional NRM bodies, farming, fishing and research bodies, community-based land-care groups and traditional owner institutions. Unfortunately, the strength of regional NRM bodies has been declining, impacting the effective implementation of aligned and multi-scale Reef 2050 Plan strategies, and particularly those related to water quality improvement. Some improvement in this sense could occur through emerging reforms that the federal Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act that explore bioregional planning and more strategic offsetting approaches to protecting catchment value and facilitating large-scale restoration.

- Toward integrated knowledge systems. Greater integration between Australian and state government knowledge systems is also needed to improve decision making across the region and to improve trust in data storage and management [90]. Communication issues were similarly highlighted by Traditional Owner communities, which emphasised the need for developing culturally appropriate knowledge systems at the sea-country estate scale [91];

- Collaborative approaches to decarbonised regional development. A significant governance challenge identified through our analysis is the lack of integrated management of the various social, economic, cultural and environmental values of the GBR and its catchments. As climate change is one of the greatest threats facing the GBR’s future, it will become increasingly important that the Reef 2050 planning process becomes increasingly supportive of, and engaged in, regional development within GBR catchments. To substitute its deep reliance on coal royalties, Queensland must undertake a major social and economic transition over the next 30 years. Several key economic reports of importance in recent years have stressed that this will specifically need to involve a significant increase in the development of higher value manufacturing and agriculture in GBR catchments, major progress in the decarbonisation of the state’s economy, and more diversified energy production. This could be conducted in highly integrated ways that massively increase the economic productivity of these catchments while at the same time scaling up the greenhouse gas emission reductions and improving GBR water quality. Doing so, however, will require research and development rich and innovative Australian, state and local government cooperation, more effective land-use and infrastructure planning, and the infusion of new science and technologies;

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COTS | Crown-of-Thorns Starfish |

| EPBC Act | Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act |

| FPIC | Free, Prior and Informed Consent |

| GBR | Great Barrier Reef |

| GBRF | Great Barrier Reef Foundation |

| GBRMP | Great Barrier Reef Marine Park |

| GBRMPA | Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority |

| GSA | Governance Systems Analysis |

| IUCN | International Union for the Conservation of Nature |

| JCU | James Cook University |

| MERI | Monitoring Evaluation Reporting and Improvement |

| NGOs | Non-Governmental Organisations |

| OUV | Outstanding Universal Value |

| RRAP | Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program |

| Reef 2050 Plan | Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan |

| RIMReP | Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting |

| QUT | Queensland University of Technology |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation |

| WH | World Heritage |

| WHC | World Heritage Commission |

References

- Camp, E.F.; Braverman, I.; Wilkinson, G.; Voolstra, C.R. Coral reef protection is fundamental to human rights. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Gooch, M.; Potts, R.; Eberhard, R. Risk analysis of the governance system affecting outcomes in the Great Barrier Reef. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 183, 712–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourian, S. Governance and forest landscape restoration: A framework to support decision-making. J. Nat. Conserv. 2017, 37, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, T.H. Evolving polycentric governance of the Great Barrier Reef. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3013–E3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldrup, S. How to measure governance: A new assessment tool. Oxf. Policy Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkki, S.; Jokinen, M.; Nijnik, M.; Zahvoyska, L.; Abraham, E.M.; Alados, C.L.; Bellamy, C.; Bratanova-Dontcheva, S.; Grunewald, K.; Kollar, J.; et al. Social equity in governance of ecosystem services: Synthesis from European treeline areas. Clim. Res. 2017, 73, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, C.A.; Steel, B.S.; Lovrich, N.P. State and Local Government and Politics: Prospects for Sustainability; Oregon State University: Corvallis, OR, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lockie, S.; Bartelet, H.A.; Ritchie, B.W.; Demeter, C.; Taylor, B.; Sie, L. Australians support multi-pronged action to build ecosystem resilience in the Great Barrier Reef. Biol. Conserv. 2024, 299, 110789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alagoz, E.; Alghawı, Y. The future of fossil fuels: Challenges and opportunities in a low-carbon. Int. J. Earth Sci. Knowl. Appl. 2024, 5, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite, J.; Drahos, P. Global Business Regulation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Martens, K.; Kaasch, A. Actors and Agency in Global Social Governance. In Actors and Agency in Global Social Governance; Martens, K., Kaasch, A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kaasch, A.; Koch, M.; Martens, K. Exploring theoretical approaches to global social policy research: Learning from international relations and inter-organisational theory. Glob. Soc. Policy 2019, 19, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mast, A.; Gill, D.; Ahmadia, G.N.; Darling, E.S.; Andradi-Brown, D.A.; Geldman, J.; Epstein, G.; MacNeil, M.A. Shared governance increases marine protected area effectiveness. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0315896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keping, Y. Governance and Good Governance: A New Framework for Political Analysis. Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 11, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addink, H. Good Governance: Concept and Context; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Borrini-Feyerabend, G.; Dudley, N.; Jaeger, T.; Lassen, B.; Broome, N.; Phillips, A.; Sandwith, T. Governance of Protected Areas: From Understanding to Action; Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 20; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2013; p. xvi+124. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. Governance for Sustainable Development: Integrating Governance in the Post-2015 Development Framework; UNDP: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Handoyo, S. Worldwide governance indicators: Cross country data set 2012–2022. Data Brief 2023, 51, 109814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. 12 Principles of Good Governance. Available online: https://thethirdway.eu/topic/good-governance/ (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- The World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/worldwide-governance-indicators (accessed on 3 February 2025).

- Biermann, F.; Pattberg, P.; van Asselt, H.; Zelli, F. The Fragmentation of Global Governance Architectures: A Framework for Analysis. Glob. Environ. Politics 2009, 9, 14–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, C.; Heinzel, M.; Jorgensen, S.; Flores, J. Bureaucratic Representation in the IMF and the World Bank. Glob. Perspect. 2022, 3, 39684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, N. The Challenge of Good Governance for the IMF and the World Bank Themselves. World Dev. 2000, 28, 823–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrik, D. Putting Global Governance in Its Place; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, M. The Good Governance Agenda: Beyond Indicators without Theory. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2008, 36, 379–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, M.-U.-I.; Emdad Haque, C.; Doberstein, B. Adaptive governance and community resilience to cyclones in coastal Bangladesh: Addressing the problem of fit, social learning, and institutional collaboration. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, R.K.; Garmestani, A.S.; Allen, C.R.; Arnold, C.A.T.; Birgé, H.; DeCaro, D.A.; Fremier, A.K.; Gosnell, H.; Schlager, E. Balancing stability and flexibility in adaptive governance: An analysis of tools available in U.S. environmental law. Ecol. Soc. 2017, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusiani, M.; Langley, A. The social construction of strategic coherence: Practices of enabling leadership. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Potts, R. Governance Systems Analysis (GSA): A Framework for Reforming Governance Systems. J. Public Adm. Gov. 2013, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- UNCTAD. Enhancing Productive Capacities and Transforming Least Developed Country Economies Through Institution-Building: Upcoming United Nations Conferences and the Way Forward; UNCTAD: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Borgström, S. Balancing diversity and connectivity in multi-level governance settings for urban transformative capacity. Ambio 2019, 48, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benham, C.F. Aligning public participation with local environmental knowledge in complex marine social-ecological systems. Mar. Policy 2017, 82, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glückler, J.; Herrigel, G.; Handke, M. On the Reflexive Relations Between Knowledge, Governance, and Space. In Knowledge for Governance; Glückler, J., Herrigel, G., Handke, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Latulippe, N.; Klenk, N. Making room and moving over: Knowledge co-production, Indigenous knowledge sovereignty and the politics of global environmental change decision-making. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douvere, F.; Badman, T. Reactive Monitoring Mission to the Great Barrier Reef (Australia): Mission Report. 2012. Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/117104/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Reef 2050 Long-Term Sustainability Plan 2021–2025; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, QLD, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vella, K.; Dale, A.; Gooch, M.; Calibeo, D.; Limb, M.; Eberhard, R.; Babacan, H.; McHugh, J.; Baresi, U. Deep Deliberation to Enhance Analysis of Complex Governance Systems: Reflecting on the Great Barrier Reef Experience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funnell, S.; Rogers, P. Purposeful Program Theory: Effective Use of Theories of Change and Logic Models; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Reinholz, D.L.; Andrews, T.C. Change theory and theory of change: What’s the difference anyway? Int. J. STEM Educ. 2020, 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.K.; Schuetz, T.; Förch, W.; Cramer, L.; Abreu, D.; Vermeulen, S.; Campbell, B.M. Responding to global change: A theory of change approach to making agricultural research for development outcome-based. Agric. Syst. 2017, 152, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Robinson, S.M.; Arms, C.; Daniels, A.E. The social, emotional and professional impact of using appreciative inquiry for strategic planning. J. High. Educ. Policy Manag. 2024, 46, 484–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratchett, M.S.; Bridge, T.C.L.; Brodie, J.; Cameron, D.S.; Day, J.C.; Emslie, M.J.; Grech, A.; Hamann, M.; Heron, S.F.; Hoey, A.S.; et al. Chapter 15—Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. In World Seas: An Environmental Evaluation, 2nd ed.; Sheppard, C., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 333–362. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, D.C.; Fulton, E.A.; Apfel, P.; Cresswell, I.D.; Gillanders, B.M.; Haward, M.; Sainsbury, K.J.; Smith, A.D.M.; Vince, J.; Ward, T.M. Implementing marine ecosystem-based management: Lessons from Australia. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2017, 74, 1990–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Concept of Governance. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/governance (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- GBRMPA. Great Barrier Reef Region Strategic Assessment: Strategic Assessment Report. Draft for Public Comment; The Reef Authority: Townsville, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: Business Strategy 2020–2025; GBRMPA: Townsville, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Reef Authority. Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program. Available online: https://www2.gbrmpa.gov.au/our-work/programs-and-projects/reef-2050-integrated-monitoring-and-reporting-program (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Leverington, A.; Leverington, F.; Hockings, M. Reef 2050 Plan Insights Report: To Inform the 2019 Outlook Report: Report to the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Reef Authority. Priority Monitoring Gaps Prospectus: Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, QLD, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, F.M. Ecocultural or biocultural? Towards appropriate terminologies in biocultural diversity. Biology 2022, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- REEFTO. Traditional Owner Implementation Plan; The Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Steering Group: Townsville, Australia, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- GBRMPA. Legislation. Available online: https://www2.gbrmpa.gov.au/about-us/legislation-and-polices/Legislation (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Reef Credit Scheme. Available online: https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/coasts-waterways/reef/reef-credit-scheme (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Davis, A.M.; Webster, A.J.; Fitch, P.; Fielke, S.; Taylor, B.M.; Morris, S.; Thorburn, P.J. The changing face of science communication, technology, extension and improved decision-making at the farm-water quality interface. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 169, 112534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commonwealth of Australia. Reef Report Cards. Available online: https://www.reefplan.qld.gov.au/tracking-progress/reef-report-card (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Commonwealth of Australia. Cane Changer. Available online: https://www.reefplan.qld.gov.au/resources/landholder-stories/cane-changer (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- NRM Regions Australia. Regional Natural Resource Management in Australia. Available online: https://nrmregionsaustralia.com.au/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Zurba, M.; Ross, H.; Izurieta, A.; Rist, P.; Bock, E.; Berkes, F. Building Co-Management as a Process: Problem Solving Through Partnerships in Aboriginal Country, Australia. Environ. Manag. 2012, 49, 1130–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girringun Aboriginal Corporation. Girringun Region Indigenous Protected Areas Management Plan; Girringun Aboriginal Corporation: Cardwell, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- GBRMPA. The Representative Areas Programme Protecting the Biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Landholders Driving Change. A Burdekin Major Integrated Project. Available online: https://ldc.nqdrytropics.com.au/ (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Hobman, E.; Mankad, A.; Pert, P.; van Putten, I.; Fleming-Muñoz, D.; Curnock, M. CSIRO Social and Economic Long-Term Monitoring Program Team (2021) Monitoring social and economic indicators among residents of the Great Barrier Reef region in 2021: A report from the Social and Economic Long-term Monitoring Program. CSIRO Land Water Aust. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Illidge, E.; Forester, T.; Depczynski, M.; Duggan, E.; Souter, D. AIMS Indigenous Partnerships Plan; Australian Institute of Marine Science: Cape Cleveland, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.; Curnock, M.; Fischer, A.; Donnelly, R.; Randall, C.J.; Foster, B. Moore Reef RRAP Demonstration Activity: Exploring Citizen Science Opportunities. Stakeholder and Traditional Owner Engagement Sub-Program Milestone. Available online: https://www.barrierreef.org/news/project-news/coral-monitoring-and-community-collaboration-at-moore-reef (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Gooch, M.; Dale, A.; Marshall, N.; Vella, K. Assessment and Monitoring of the Human Dimensions Within the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: Final Report of the Human Dimensions Expert Group; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- GBRMPA. Reef Snapshot: Summer 2023-24; Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority: Townsville, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Star, M.; Rolfe, J.; Farr, M.; Poggio, M. Transferring and extrapolating estimates of cost-effectiveness for water quality outcomes: Challenges and lessons from the Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021, 171, 112870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukasiewicz, A.; Vella, K.; Mayere, S.; Baker, D. Declining trends in plan quality: A longitudinal evaluation of regional environmental plans in Queensland, Australia. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Yorkston, H.; Potts, R. A method for risk analysis across governance systems: A Great Barrier Reef case study. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 015037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, M.; Karen, V.; Nadine, M.; Renae, T.; Pears, R. A rapid assessment of the effects of extreme weather on two Great Barrier Reef industries. Aust. Plan. 2013, 50, 198–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vella, K.; Cole-Hawthorne, R.; Hardaker, M. The Value Proposition of Regional Natural Resource Management in Queensland: Final Report; Queensland University of Technology: Brisbane, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, Z.; Day, J. Biodiversity of the Great Barrier Reef-how adequately is it protected? PeerJ 2018, 6, e4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobman, E.V.; Michelle, D.; Samantha, S.-J.; Maxine, N.; Tracy, S.; Kirsten, M.; Claudia, B.; Natalie, J.; Dean, A.J. Understanding and monitoring Reef stewardship: A conceptual framework and approach for the Great Barrier Reef. Australas. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 65–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liburd, J.J.; Becken, S. Values in nature conservation, tourism and UNESCO World Heritage Site stewardship. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1719–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baresi, U.; Eberhard, R.; Vella, K.; Gooch, M.; Piggott-McKellar, A.; Calibeo, D.; Lockie, S.; Taylor, B.; Bohensky, E.; Brooksbank, L.; et al. Community Engagement for Novel Ecosystem Restoration and Assisted Adaptation Interventions: Observations and Lessons from the Australian Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2025, 38, 626–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, I.; Hein, M.; Babcock, R.; Bay, L.; Bourne, D.; Cook, N.; Doropoulos, C.; Gibbs, M.; Harrison, P.; Lockie, S.; et al. Coral restoration and adaptation in Australia: The first five years. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0273325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, M.L.; Datta, A.; Morris, S.; Zethoven, I. Navigating climate crises in the Great Barrier Reef. Glob. Environ. Change 2022, 74, 102494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivapalan, M.; Bowen, J. Decision frameworks for restoration & adaptation investment–Applying lessons from asset-intensive industries to the Great Barrier Reef. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Ryan, S.; Broderick, K.; Hill, R.; Potts, R.; Brewer, T. Governing community-based natural resource management in Australia: International Implications. Land 2020, 9, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Kulmie, D. Role of Effective Monitoring and Evaluation in Promoting Good Governance in Public Institutions. Public Adm. Res. 2023, 12, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emslie, M.J.; Bray, P.; Cheal, A.J.; Johns, K.A.; Osborne, K.; Sinclair-Taylor, T.; Thompson, C.A. Decades of monitoring have informed the stewardship and ecological understanding of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 252, 108854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamman, E.; Brodie, J.; Eberhard, R.; Deane, F.; Bode, M. Regulating land use in the catchment of the Great Barrier Reef. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.A.; Williamson, D.H.; Beeden, R.; Emslie, M.J.; Abom, R.T.M.; Beard, D.; Bonin, M.; Bray, P.; Campili, A.R.; Ceccarelli, D.M.; et al. Protecting Great Barrier Reef resilience through effective management of crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, E.; Fisher, M.; Mackean, T.; Baum, F. Implementing ‘Closing the Gap’ policy through mainstream service provision: A South Australian case study. Health Promot. J. Austr. 2025, 36, e884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parter, C.; Murray, D.; Mohamed, J.; Rambaldini, B.; Calma, T.; Wilson, S.; Hartz, D.; Gwynn, J.; Skinner, J. Talking about the ‘r’ word: A right to a health system that is free of racism. Public Health Res. Pract. 2021, 31, e3112102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Satterfield, T. Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conserv. Lett. 2018, 11, e12600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Gooch, M.; Potts, R.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Eberhard, R. Avoiding Implementation Failure in Catchment Landscapes: A Case Study in Governance of the Great Barrier Reef. Environ. Manag. 2018, 62, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dale, A.; Vella, K.; Pressey, R.; Brodie, J.; Gooch, M.; Potts, R.; Eberhard, R. Monitoring and Adaptively Reducing System-Wide Governance Risks Facing the GBR: Final Report; Reef and Rainforest Research Centre: Cairns, Australia, 2016; p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Dale, A.; Curnow, J.; Campbell, A.; Seigel, M. Introduction to subsidiarity and landcare: Building local self-reliance for global change. In Building Global Sustainability Through Local Self-Reliance: Lessons from Landcare; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR): Canberra, Australia, 2022; Volume ACIAR Monograph No. 219. [Google Scholar]

- MacKeracher, T.; Diedrich, A.; Gurney, G.G.; Marshall, N. Who trusts whom in the Great Barrier Reef? Exploring trust and communication in natural resource management. Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 88, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, K.; Inc, T. Crossing cultural boundaries: Integrating Indigenous water knowledge into water governance through co-research in the Queensland Wet Tropics, Australia. Geoforum 2015, 59, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxwell-Norton, K.; Konkes, C. Is the Great Barrier Reef dead? Satire, death and environmental communication. Media Int. Aust. 2022, 184, 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piggott-McKellar, A.E.; McNamara, K.E. Last chance tourism and the Great Barrier Reef. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 397–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Coherence | Connectivity and Capacity | Knowledge | Operational Governance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared vision | Process transparency and trust among actors | Knowledge quality, availability and access | Efforts deliver effective and efficient outcomes |

| Integrated legal framework | Actor capacities and skills | Informed consent about knowledge use | Sustainability of actions taken |

| Integrated legal framework | Equity in collaboration and genuine partnerships | Diversity of knowledge | Application of risk management |

| Cohesive implementation | Open and diverse communication flows | Knowledge integration and decision support | Timeliness of effort |

| Monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement (MERI) systems | System subsidiarity | Knowledge storage and management systems | Adequacy of resources |

| Rating Scale | Definition |

|---|---|

| Healthy | The attribute is functioning effectively and consistently across the Reef 2050 Plan governance system, with strong coordination, implementation and continuous improvement evident at all levels. |

| Maturing | The attribute is generally working well within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system, though some areas show room for enhancement in consistency, integration or effectiveness. |

| Emergent | The attribute is only partially functional across the Reef 2050 Plan governance system, with limited application, coordination gaps or inconsistent implementation undermining overall performance. |

| Underdeveloped | The attribute is largely absent or ineffective within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system, with significant deficiencies in structure, coordination or practical application. |

| Coherence: Is the Governance System Cohesive Across Vision and Goal Setting, Strategy Development, Implementation and Monitoring and Review? | |||

| Attribute | Assessment | Case Study | Some Examples of Key Findings |

| Shared vision: All actors involved in development and implementation of the Reef 2050 Plan share complementary visions for the GBR. | Maturing | The Reef 2050 Traditional Owner Implementation Plan [51] | More efforts are needed to strengthen partnerships between governments and key industries, Traditional Owners and others to enable collective vision setting, especially at smaller scales within the whole of GBR scale. |

| Integrated legal framework: From the global to the state scale, there is an impactful set of legislative and policy instruments integrated across key issues affecting the GBR and across global, national, state and local scales. | Maturing | The GBRMP Act and the Reef Authority [52] | GBR-related legislative frameworks need to be updated and better integrated to reflect the current magnitude of stressors on GBR health, including links between policies developed under the GBRMP Act (1975), the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999) and those pertaining to emissions reduction. Greater legislative linkage is needed across multiple legislative instruments that contribute to the Reef 2050 Plan. |

| Aligned multi-scale and prioritised strategies: Reef 2050 Plan strategies and associated delivery arrangements are diverse and well targeted enough to achieve the plan’s goals. | Emergent/maturing | The Reef Credit Scheme [53] | Transparent and rigorous processes are needed to prioritise investment in strategies and actions implemented under the Reef 2050 Plan to reduce siloed decision making and fragmentation of multi-scalar efforts. |

| Cohesive implementation: Strategies are effectively coordinated, delivered and maintained on the ground. | Emergent | Project 25 [54] | This assessment detected a general decline in the consistency and coordination of wide-scale implementation efforts, despite evidence of some programmes showing consistent long-term benefits for GBR health. |

| Monitoring, Evaluation, Reporting & Improvement (MERI) systems: Active monitoring, evaluation and review of Reef 2050 Plan efforts across scales, resulting in continuous improvement. | Maturing | Reef Water Quality Report Cards [55] | There is strong commitment to multi-scale MERI frameworks across the system, although some GBR-project-delivery partners have concerns about their complexity. RIMReP, designed to coordinate all monitoring and evaluation efforts underpinning progress toward Reef 2050 Plan, represents sound practice, but there are major timeline delays. |

| Connectivity and Capacity: Are Governance System Components Deeply Connected Both Vertically and Horizontally, with Equitable Capacity Present Across All Actors? | |||

| Attribute | Assessment | Case Study | Some Examples of Key Findings |

| Process transparency and trust among actors: Across scales, decision making processes are transparent and accountable, and there are high levels of trust between the actors involved. | Emergent/maturing | Cane Changer [56] | There are reasonable levels of public trust in key agencies involved in GBR governance, although some industries and local governments within the GBR catchment have lower levels of trust in Commonwealth and state-government management agencies. There has, however, been some recent progress in relation to enhanced transparency and trust between Traditional Owners and lead GBR agencies. |

| Actor capacities and skills: All key actors in the GBR have the capacities and skills needed to fulfil their responsibilities and they are actively supported. | Maturing | Regional NRM: The Australian Business Excellence Framework for NRM [57] | Core capacities of government agencies appear to be reasonable, but there are poor capacities for building long-term relationships for subsidiarity, especially in community, industry and Traditional Owner sectors. |

| Equity in collaboration and genuine partnerships: There is demonstrable power sharing across all GBR actors leading to genuine partnership effort. | Emergent/maturing | Girringun TUMRA [58,59] | Although there are strengthening collaborations between the Commonwealth, the State and the Reef Authority and stronger partnerships with GBR Traditional Owners, more genuine partnerships are needed with industry, local government and regional NRM bodies. |

| Open and diverse communication flows: Policies, plans, information and progress is freely shared across all actors and the broader community. | Maturing | GBR Representative Areas Program [60] | There is a need to improve two-way communication between GBR management agencies, key actors and wider society. Large-scale surveys such as SELTMP, social research, rich conversations and independent moderators can facilitate knowledge exchange and deepen understanding between people and institutions. |

| System subsidiarity: The power to make the right decisions rests with those actors closest to the policy, planning or delivery problem being addressed. | Underdeveloped/emergent | Burdekin Major Integrated Project [61] | Subsidiarity is poorly recognised, understood and conceptualised within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system. Targeted investment in the capacity of regional and localised groups is needed to increase the chances of success for major policies and programmes emerging from the Reef 2050 Plan. |

| Knowledge: Are Diverse Forms of Knowledge, Data, Research, Development and Innovation Appropriately Considered in Decision Making? | |||

| Attribute | Assessment | Case Study | Some Examples of Key Findings |

| Knowledge quality, availability and access: The knowledge needed in decision making at all scales has high integrity, is readily available and can be accessed. | Maturing | Social and Economic Long-Term Monitoring Program (SELTMP) for the GBR [62] | GBR agencies have access to a wide variety of data through sophisticated systems for knowledge generation and real-time information sharing. This enables rapid management responses. However, significant gaps remain in understanding cumulative impacts on GBR health. |

| Informed consent about knowledge use: Free, prior informed consent is well negotiated when collecting and using knowledge and data from human sources. | Emergent/maturing | Establishment of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) [63] | The increasing use of Free Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) agreements is empowering Traditional Owners with right of veto on sea country, significantly changing GBR long-term management arrangements. Many farmers in the catchment, however, remain concerned about GBR managers’ increased use of high-tech tools for data that may be collected without informed consent. |

| Diversity of knowledge: Decision making in the governance system uses a diverse range of social, cultural, economic, biophysical, traditional, historical and industry knowledge. | Emergent/maturing | Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP) Collaborative Monitoring Project [64] | Biophysical knowledge about the GBR is ever-expanding and is used effectively to inform management. Even so, more effort is needed to include knowledge and perspectives of farmers, Traditional Owners, fishers and citizen scientists into GBR decision making. |

| Knowledge integration and decision support: Data and knowledge are well integrated in effective modelling and decision support systems. | Emergent/maturing | Reef Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program (RIMReP)’s Human Dimensions Monitoring [65] | Varying degrees of knowledge integration for collective decision making occurs across the GBR for a variety of purposes, but knowledge gaps remain. These gaps hamper decision making and limit negotiations with GBR actors about options for the future. |

| Knowledge storage and management systems: There are strong knowledge management and sharing platforms in place, enabling effective decision making. | Emergent/maturing | Summer Snapshot for the GBR [66] | Sophisticated knowledge storage and management systems are in place within GBR agencies. However a lack of trust and few inter-linked knowledge management systems have created institutional silos, which prevent access within and among management organisations. |

| Operational Governance: Operationally, Is the Governance System Adaptive and Robust Enough to Achieve Its Intended Vision? | |||

| Attribute | Some Key Examples of Findings | Case Study | Assessment |

| Efforts deliver effective and efficient outcomes: The Reef 2050 Plan governance system delivers the right (effective) interventions well (efficiently), delivering intended Plan outcomes. | Underdeveloped/emergent | Cost-Effective Measures to Improve Water Quality in GBR Catchments [67] | Some programmes within the Reef 2050 Plan can demonstrate progress toward targets, such as the Crown-of-Thorns Starfish (COTS) control initiative. For other initiatives (e.g., water quality improvement) it has been much harder to demonstrate effective and efficient outcomes. |

| Sustainability of actions taken: Reef 2050 Plan actions can be continued adaptively until they achieve their goals and targets. | Underdeveloped/emergent | Evolution of NRM arrangements and plans in Queensland [68] | Effective GBR governance requires long-term, coordinated and sustained efforts based on trade-offs and priorities; however, in the Reef 2050 Plan governance system, many strategic actions have not been consistently maintained and sustained in the longer-term. |

| Application of risk management: Risks are adequately considered and managed across scales within the design and implementation of GBR interventions. | Emergent/maturing | Framework for Governance Systems Analysis (GSA) [69] | Within the Reef 2050 Plan governance system, several specific applications of risk analysis exist, including risk assessment, response and monitoring. Consideration of the social, ecological, cultural and economic dimensions of risk is evident in some areas, however in general, the social and cultural dimensions do not appear to be routinely included. |

| Timeliness of effort: Interventions across the Reef 2050 Plan are timed to maximise successful goal achievement. | Emergent/maturing | Response to Extreme Weather: The Wet Season 2010–2011 [70] | Flexible management arrangements and new technologies that generate near real-time data enable rapid responses to disasters such as cyclones, COTS outbreaks, flooding and bleaching. However, these responses must be bolstered by increased system subsidiarity involving local actors together with urgent global efforts to address the impacts of climate change on GBR health. |

| Adequacy of resources: Sufficient resources are allocated to enable the success of all Reef 2050 Plan interventions. | Underdeveloped/emergent | The regional NRM sector in the GBR [71] | There has been significant growth in investment in GBR programmes over the past twenty years, resulting in some progress toward securing more equitable and enduring funding. There are, however, serious funding short-falls to deliver on the Reef 2050 Plan outcomes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vella, K.; Dale, A.P.; Calibeo, D.; Limb, M.; Gooch, M.; Eberhard, R.; Babacan, H.; McHugh, J.; Baresi, U. The Health of the Governance System for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef 2050 Plan: A First Benchmark. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188131

Vella K, Dale AP, Calibeo D, Limb M, Gooch M, Eberhard R, Babacan H, McHugh J, Baresi U. The Health of the Governance System for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef 2050 Plan: A First Benchmark. Sustainability. 2025; 17(18):8131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188131

Chicago/Turabian StyleVella, Karen, Allan Patrick Dale, Diletta Calibeo, Mark Limb, Margaret Gooch, Rachel Eberhard, Hurriyet Babacan, Jennifer McHugh, and Umberto Baresi. 2025. "The Health of the Governance System for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef 2050 Plan: A First Benchmark" Sustainability 17, no. 18: 8131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188131

APA StyleVella, K., Dale, A. P., Calibeo, D., Limb, M., Gooch, M., Eberhard, R., Babacan, H., McHugh, J., & Baresi, U. (2025). The Health of the Governance System for Australia’s Great Barrier Reef 2050 Plan: A First Benchmark. Sustainability, 17(18), 8131. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17188131