1. Introduction

As the global economy rapidly evolves, entrepreneurship has emerged as a vital career choice, particularly for college students seeking alternatives to traditional employment [

1,

2,

3]. The quality and accessibility of entrepreneurship education play a pivotal role in shaping such opportunities [

4]. The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor [

5] reinforces this trend by emphasizing the need to cultivate entrepreneurial skills early, especially in light of increasing female unemployment rates.

Previous research has primarily focused on entrepreneurial intentions, resulting in a gap in understanding students’ actual career outcomes following entrepreneurship education [

6]. Moreover, while the gender gap in entrepreneurship is well documented in Western contexts, there is limited research addressing this issue within China’s distinct cultural, social, and economic environment, which significantly influences female students’ career decisions [

7]. This study seeks to address these gaps by investigating how entrepreneurship education—specifically through courses, competitions, practices, and policy initiatives—affects the entrepreneurial career choices of female college students in China.

Grounded in human capital and stereotype threat theories, this research analyzes data from 24,508 female students across 31 provinces in China to provide empirical insights into how distinct educational factors influence women’s entrepreneurial career choices. By evaluating the differential effects of various educational components, this study advances theoretical understanding and offers practical recommendations for improving entrepreneurship education, particularly in developing contexts.

This research is guided by three key questions:

RQ1: Does entrepreneurship education influence female university students’ choice of entrepreneurship as a career?

RQ2: Which dimension of entrepreneurship education—courses, competitions, practices, or policies—most significantly predicts career orientation toward entrepreneurship?

RQ3: What strategies within entrepreneurship education can effectively support the entrepreneurial aspirations of female students?

This study addresses a critical gap in the literature concerning gender and entrepreneurship but also provides actionable recommendations for policymakers and educational institutions to foster more inclusive and effective entrepreneurship education. The findings aim to inform future educational reforms and contribute to the global discourse on gender equity in entrepreneurship, with implications for both scholars and practitioners.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Female Entrepreneurship

Achieving sustainable development necessitates the active participation of women across political, social, and economic spheres [

8,

9]. Policymakers increasingly recognize women as key contributors to entrepreneurial talent, economic growth, and wealth creation [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Nevertheless, women remain underrepresented in new venture creation [

14], primarily because of environmental factors that create unique challenges for their entrepreneurial pursuits [

11]. Gender stereotypes often discourage women from entrepreneurship, restricting their access to essential resources and impeding business performance [

15]. Gender stereotype theory further posits that societal norms may prompt women to self-stereotype, aligning their aspirations with prevailing expectations [

16], which may contribute to lower entrepreneurial intentions among women [

17].

Research indicates that women are often motivated to pursue self-employment by the need to balance family and work responsibilities, while men typically engage in entrepreneurship for self-actualization and other intrinsic rewards [

18,

19]. Accordingly, entrepreneurship support programs, including targeted education, can play a crucial role in empowering female students, especially within five years post-graduation. However, stereotype threat theory suggests that social stereotypes still discourage female college students from entrepreneurial careers. Existing entrepreneurship promotion strategies tend to be male-oriented and rarely address the specific needs of female entrepreneurs [

20,

21]. As a result, female-led enterprises are often smaller and have less access to financing, with women encountering greater difficulties in obtaining credit compared to men [

22]. As a critical contextual factor, entrepreneurship education holds potential for addressing gender disparities in entrepreneurship, underscoring the importance of examining its impact on female students’ career decisions.

2.2. Entrepreneurial Career Choices

Career choice encompasses options such as starting a business, looking for a job, pursuing further education, or other options. Economic research establishes entrepreneurship as a viable career path [

23], with career choice theory suggesting that high unemployment lowers the relative costs of self-employment, making entrepreneurship more appealing [

24,

25]. However, many unemployed individuals lack the necessary “human capital and entrepreneurial talent”—such as education, experience, and skills—required to sustain and grow a business, particularly among youth. Conversely, new businesses contribute to job creation and help mitigate unemployment by driving innovation, productivity, and competitiveness [

26]. For many, entrepreneurship represents a lifelong career aspiration, especially in contexts of high unemployment, where increased entrepreneurial activity can help alleviate joblessness [

24].

There are many factors that influence female career choices in entrepreneurship, such as rapid economic growth, social and cultural influence, and family factors [

27]. Furthermore, entrepreneurship education is essential for fostering entrepreneurial intentions among female students, as it equips them with the skills and confidence needed to pursue self-employment [

28].

2.3. Entrepreneurship Education

Entrepreneurship education encompasses programs or processes aimed at fostering entrepreneurial attitudes and skills [

29]. Scholars widely agree that such education and training enhance the entrepreneurial abilities of college students, transforming these capabilities into a form of human capital that improves opportunity recognition and facilitates entrepreneurial career choices [

30,

31].

The dynamic view of human capital suggests that general human capital—acquired through education—provides the discipline, motivation, self-confidence, skills, and knowledge necessary for adapting to evolving situations [

32]. Human capital is central to business success, with entrepreneurial firms relying heavily on the human capital of their employees as a key driver of economic growth and innovation [

30]. Entrepreneurship education serves as a primary means of developing this human capital by raising students’ awareness of entrepreneurial opportunities and strengthening their commitment to entrepreneurship, thereby enabling them to plan more deliberately for their futures [

33].

Research further indicates that entrepreneurship education influences cognitive factors, such as self-efficacy and fear of failure, which significantly shape an individual’s decision to start a business [

34,

35]. Recent studies highlight the pivotal role of entrepreneurship education in fostering entrepreneurial knowledge, competencies, and attitudes, recognizing it as a central driver of entrepreneurial outcomes [

36]. However, female entrepreneurs often face limited access to education, training, and career development opportunities [

37]. A major challenge for women remains the prevalence of gender-based stereotypes and persistent gender gaps within the business world, both of which hinder women from seizing entrepreneurial opportunities [

38]. Universities play a crucial role in nurturing future female entrepreneurs and are the main institutions responsible for the successful implementation of women’s entrepreneurship education. Female entrepreneurship education aims to equip female students with the necessary knowledge, skills, and experiential learning—delivered through tailored courses, competitions, and practical opportunities—to develop strong entrepreneurial capabilities and address the unique challenges encountered in the business world [

39]. Entrepreneurship education can enhance female business knowledge, boost self-confidence, expand social support networks, and help reduce gender biases, significantly increasing their likelihood of choosing entrepreneurship as a career.

2.3.1. Entrepreneurship Courses

Entrepreneurship courses, as structured academic offerings centered on entrepreneurial theories and practices, play a pivotal role in cultivating students’ entrepreneurial competencies [

40]. According to Motta et al. [

41], such courses are the primary means through which universities deliver entrepreneurship-related content, emphasizing both theoretical foundations and practical application. Through these courses, students can systematically acquire business knowledge, develop entrepreneurial skills, and gain exposure to the entrepreneurial process, which, in turn, enhances their entrepreneurial intention (EI). Prior studies have shown that entrepreneurship courses significantly improve students’ understanding of business operations and increase their confidence in pursuing entrepreneurial careers [

42,

43]. Based on these findings, Hypothesis 1 is proposed.

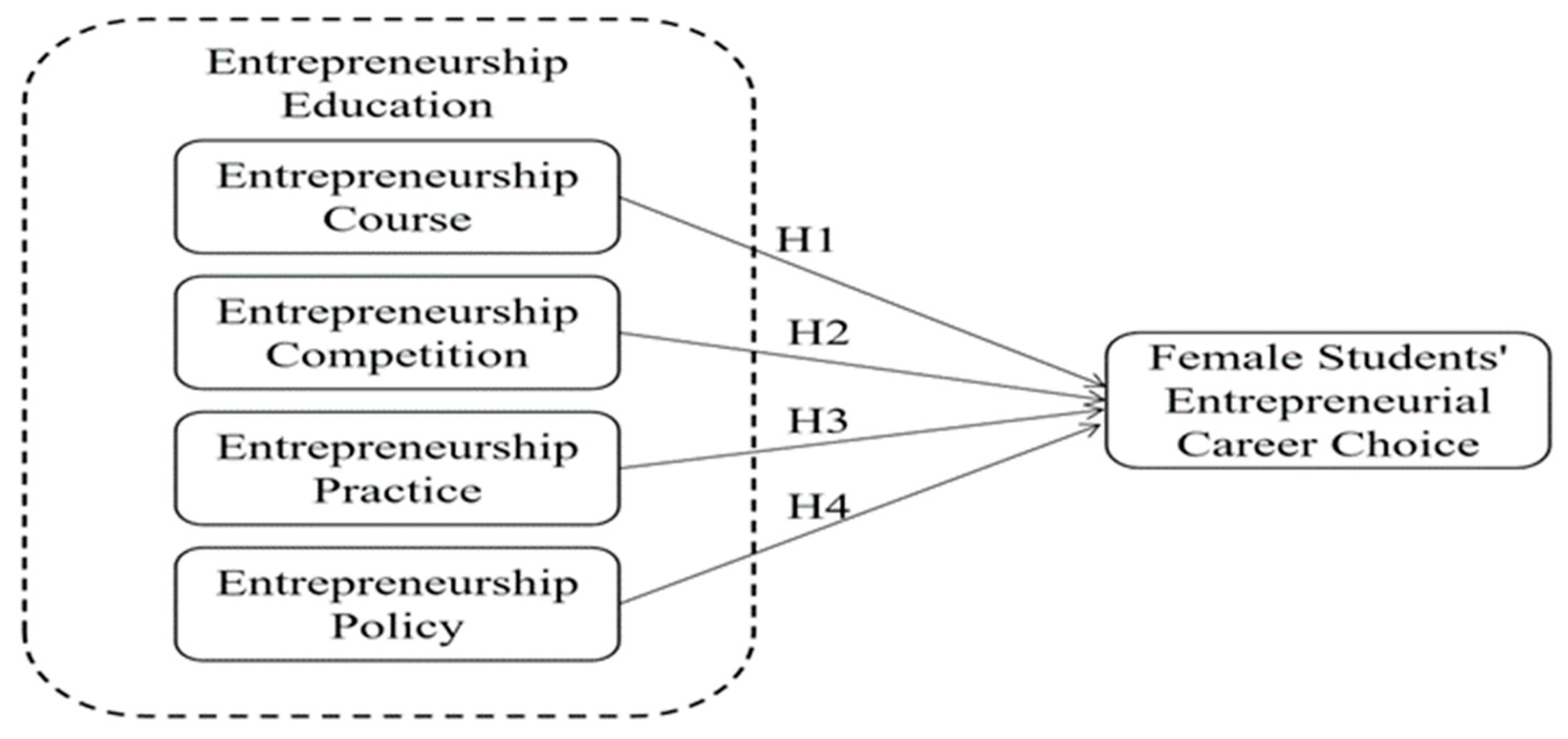

Hypothesis 1. Entrepreneurship courses have a predictive effect on female students’ entrepreneurial career choices.

2.3.2. Entrepreneurship Competitions

Entrepreneurship competitions are the integration of knowledge and practice, which is conducive to promoting students’ understanding of the entrepreneurial practice process [

44]. As a practice in entrepreneurship education, entrepreneurship competitions can cultivate students’ innovative thinking and contribute to better promoting entrepreneurship [

45]. Wang [

46] demonstrates that entrepreneurial competitions can have a significant positive effect on college graduates’ participation in self-employment. Based on this, Hypothesis 2 was proposed.

Hypothesis 2. Entrepreneurship competitions have a predictive effect on female students’ entrepreneurial career choices.

2.3.3. Entrepreneurial Practice

Entrepreneurial practice refers to the behavioral experience and resource utilization of students participating in real or simulated entrepreneurial activities within universities or school enterprise joint construction platforms [

47]. Entrepreneurship is mostly learned through practice [

48,

49]. Practice-based entrepreneurship education can enhance students’ understanding and application of knowledge, which is a manifestation of the implementation effect of entrepreneurship education and can enhance confidence in entrepreneurship education [

50]. Engaging in entrepreneurial practices enables students to effectively apply their entrepreneurial knowledge in real-world settings. Gaining hands-on experience through such practices is essential for developing entrepreneurial capabilities [

51]. Based on this, Hypothesis 3 was proposed.

Hypothesis 3. Entrepreneurial practice has a predictive effect on female students’ entrepreneurial career choices.

2.3.4. Entrepreneurship Policy

Entrepreneurship policy refers to the perceived support measures introduced by the government or schools for college students’ entrepreneurship [

52], including tax and financial support. College students, like most potential entrepreneurs, often give up on entrepreneurship because of a lack of funding and policy support [

35]. Based on this, Hypothesis 4 was proposed.

Hypothesis 4. Entrepreneurship policy has a predictive effect on female students’ entrepreneurial career choices.

Based on the above four hypotheses and entrepreneurship education’s significant impact on college students’ entrepreneurial career choices [

53], this study examined how entrepreneurship education affects female college students’ entrepreneurial career choices. A model illustrating the factors influencing female students’ entrepreneurial career choices is presented in

Figure 1.

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Participants and Procedure

Our research team conducted a randomized survey using questionnaires with female students and graduates who had received entrepreneurship education across six provinces in China, including municipalities directly under the central government. The data collection process involved a combination of on-site and commissioned investigations. We asked colleagues, alumni, and friends employed at these universities to distribute the questionnaires electronically to students. The survey was conducted from June to December 2023. After data collection, screening, and sorting, a final sample of 24,508 female students was selected. The questionnaire gathered information on students’ demographics, participation in entrepreneurship courses, competitions, practices, policies, and entrepreneurial career choices. Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale, where 5 represented “strongly agree,” 4 “relatively agree,” 3 “average,” 2 “relatively disagree,” and 1 “strongly disagree”.

To ensure representativeness, the sample comprised both current students and recent graduates (within five years) to capture a broad range of employment perspectives. Researchers consistently followed ethical standards during all phases of the study. The participants provided informed consent, confirming their understanding of the research objectives and voluntary participation. They were assured of the confidentiality of their responses, and the research team guaranteed that their identities would remain protected. All collected data were solely for academic research purposes, in line with the institution’s ethical standards. Descriptive statistics for the sample are summarized in

Table 1.

3.2. Reliability and Validity Test

This study used multiple logistic regression to directly assess the influence of the different dimensions of entrepreneurship education on female students’ entrepreneurship career choices. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the measurement model of the study variables (

Table 2). The composite reliability (CR) of all constructs exceeded 0.70, confirming internal consistency reliability. In addition, Cronbach’s α values of each factor were above 0.8, indicating good reliability of the scale. The average variance extracted (AVE) values of the constructs exceeded the suggested benchmark of 0.50 and proved to have reasonable convergent validity. Furthermore,

Table 3 illustrates that the square root of the AVE was higher than the value of the corresponding row and column, which supports discriminant validity [

54]. We examined the fit of a model in which indicators loaded on one factor (

Table 4), partly addressing common method variance (CMV) concerns regarding the measures used in this study. The chi-squared test value difference between the two models was significant (ΔCMIN2 = 103,686.677, ΔDF = 6,

p < 0.05), indicating that there was no significant CMV. As indicated in

Table 4,

p < 0.001, CMIN/DF = 151.318, RMSEA = 0.078 < 0.08, RMR = 0.023 < 0.05, GFI = 0.903 > 0.9, NFI = 0.956 > 0.9, CFI = 0.956 > 0.9, and IFI = 0.956 > 0.9. Regarding the fitting index of the structural equation, all fit indices reached the standard, indicating that the scale had good structural validity [

54]. Furthermore, variance inflation factor values (VIF) are commonly utilised to assess multicollinearity, as suggested by Kock and Lynn [

55]. The VIF values for all variables are below 3.3, indicating a lack of substantial collinearity.

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. The General Status of Female College Students’ Entrepreneurship Education

Table 5 illustrates the level of satisfaction with detailed indicators of various dimensions in the evaluation of female college students’ entrepreneurship education. It includes the mean satisfaction for the four dimensions of entrepreneurship: course, competition, practice, and policy.

3.3.2. Current Situation of Entrepreneurship Education

A single-sample t-test was conducted to assess the four dimensions of entrepreneurial education. First, the results suggest that female college students were relatively satisfied with six indicators of the entrepreneurship education curriculum. Students’ satisfaction scores for item A6, ‘Entrepreneurship course content closely combined with cutting-edge,’ were higher than the indicators of the other two courses, which suggests that current entrepreneurship course content is relatively up to date.

Second, the results suggest that female college students were satisfied with the five indicators of entrepreneurship competitions. Among them, students’ satisfaction with the following items was relatively high: B4, ‘Entrepreneurship competition improves team cooperation ability;’ B5, ‘Entrepreneurship competition is of great help to real entrepreneurship;’ and B1, ‘Entrepreneurship competition improves entrepreneurial ability’.

Third, this study investigated female college students’ participation in entrepreneurial practices. The results showed that female college students were relatively satisfied with five indicators. Among them, the satisfaction scores for ‘college students’ entrepreneurship park’ (C3) and ‘venture capital fund support’ (C4) were relatively high, while the other three scores were lower and similar. This finding indicates that college student entrepreneurship parks and financial support are helpful in female college students’ entrepreneurship. In combination with the above-mentioned item A5, ‘Close combination of entrepreneurship courses and majors,’ the degree of satisfaction with C5, ‘Close combination of entrepreneurial practice and professional learning,’ was relatively low; this indicates that the integration of entrepreneurial learning with students’ academic disciplines needs enhancement.

Finally, the results showed that female college students were relatively satisfied with these four indicators of policy support, among which their satisfaction with school (D3) and society (D4) policies was lower than with national (D1) and local (D2) government policies. This indicates that the policy support effect of schools and society on student entrepreneurship is relatively poor.

3.3.3. Influence of Entrepreneurship Education on Female College Students’ Entrepreneurship Choices

Entrepreneurship courses, policies, competitions, and practices constitute the primary components of entrepreneurship education in China. To examine the influence of these components on entrepreneurial choice, we conducted a multiple logistic regression analysis assessing whether entrepreneurship education affects the likelihood of female college students choosing to start their own businesses. The study question regarding entrepreneurial choice was, ‘What is your most desired plan after graduation?’

Table 1 presents the statistical results of female college students’ entrepreneurial choices.

In our analysis, we used ‘entrepreneurship course,’ ‘entrepreneurship policy,’ ‘entrepreneurship competition,’ and ‘entrepreneurship practices’ as the independent variables; ‘entrepreneurship choice’ as the dependent variable; and ‘starting a business’ as the reference category. As illustrated in

Table 6,

p < 0.05, indicating that the model fits well, and the independent variables in the model are meaningful.

The results of this analysis are presented in

Table 7. The formulas for the model are as follows:

4. Results

The results of our analysis are as follows: First, when comparing the choices of ‘looking for a job’ versus ‘starting a business,’ both entrepreneurship courses and entrepreneurship competitions had a statistically significant influence on the decision to pursue entrepreneurship (p < 0.05). The coefficients for entrepreneurship competitions (A = −0.180) and entrepreneurship courses (B = −0.111) were negative, indicating that higher satisfaction with these components increased the likelihood that female college students would choose self-employment. Second, in the comparison between ‘further education’ and ‘starting a business,’ the influence of entrepreneurship competitions and entrepreneurship courses were again statistically significant (p < 0.05), and the coefficients of entrepreneurship courses and entrepreneurship competitions were both negative (A = −0.212 and B = −0.116, respectively).This suggests that greater satisfaction with these aspects of entrepreneurship education was associated with a higher propensity to start a business. Third, in the choice between ‘other’ and ‘starting a business,’ entrepreneurship competitions had a statistically significant effect (p < 0.05), and the entrepreneurship competitions coefficient was negative (B = −0.305), indicating that increased satisfaction with entrepreneurial competitions encouraged students to start their business. According to the results, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported, but Hypotheses 3 and 4 were not.

5. Discussion

This study explores how entrepreneurship education influences the entrepreneurial career choices of female college students, using a large-scale empirical sample from China. The findings reveal that entrepreneurship courses and competitions have a positive effect on students’ entrepreneurial choices, while entrepreneurial practices and policies do not show significant impact. These findings highlight the importance of critically evaluating the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education [

56]. Specifically, courses and competitions appear to enhance entrepreneurial skills and motivation among female students, thereby supporting their pursuit of entrepreneurial careers. However, the limited impact of practices and policies, which diverges from previous research [

35], suggests the presence of unique challenges in these domains.

This discrepancy may be explained by our hypotheses that (a) regarding gender differences, psychological and physiological factors may limit women’s inclination to entrepreneurship despite supportive policies, and (b) group-specific effects may reflect a reduced efficacy of policies designed for a broader student population, as this study’s focus was on female college students.

Supporting Yousaf et al. [

57], our study reaffirms that entrepreneurship education strengthens students’ abilities and intentions toward entrepreneurship as a career path. Furthermore, it extends Adeel et al.’s [

56] work by explicitly analyzing gender and group differences, emphasizing the distinct role of entrepreneurship education for female students. This finding aligns with Hägg et al. [

58], reinforcing the argument that tailored entrepreneurship education can help mitigate gender imbalances in the field.

Finally, by addressing the complex, interactive aspects of entrepreneurial processes [

59,

60], this study contributes to a nuanced understanding of entrepreneurship education as an external, yet influential, factor in entrepreneurial career choices. These insights offer valuable directions for future research focused on refining entrepreneurial practices and strengthening policies to better support female entrepreneurs.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This research makes a notable theoretical contribution by examining how entrepreneurship education shapes the career choices of female college students, extending beyond prior studies that focused primarily on single professions or general entrepreneurial intentions [

61,

62]. By applying human capital theory and incorporating feminist perspectives, this study broadens the analytical framework and enhances understanding of the diverse outcomes of entrepreneurship education. Unlike earlier research that often assessed overall impacts [

57], this investigation provides a detailed analysis of how specific elements—courses, competitions, practices, and policies—uniquely influence entrepreneurial career choices, thereby building a robust theoretical foundation for future studies.

The findings serve as a valuable reference for young entrepreneurs in other developing countries, particularly in rapidly growing economies [

63], thereby extending the study’s relevance and applicability to a global scale. This nuanced approach not only elucidates the roles of individual educational components in fostering entrepreneurial aspirations but also highlights the need for customized educational strategies to support female entrepreneurship, especially in dynamic economic environments.

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.2.1. Female Entrepreneurship Course: Personalized Support and Mentorship System

To encourage female entrepreneurs, entrepreneurship courses should provide personalized support and establish a mentorship system specifically for women. These courses can address specific challenges women face during entrepreneurship, such as difficulties in obtaining funding, gender bias, and social and cultural barriers, offering customized content and resources. For instance, the course should include topics on how to secure funding specifically tailored for female entrepreneurs, how to overcome workplace gender barriers, and how to leverage the unique leadership advantages women possess. Additionally, the program could feature female mentors or successful female entrepreneurs as role models, helping students build confidence and receive practical guidance and support for their ventures. The mentorship system can offer personalized coaching and psychological support, helping female students overcome challenges in the actual entrepreneurial process, while enhancing their entrepreneurial skills and leadership abilities.

5.2.2. Enhancing the Appeal and Relevance of Entrepreneurship Competitions

To better support female entrepreneurs, it is recommended to organize dedicated entrepreneurship competitions focusing on the unique challenges women face, such as resource acquisition, network building, and market entry. These competitions should not only offer awards and funding but also emphasize mentorship, inviting experienced female entrepreneurs or experts to provide personalized guidance to participants. This will help them address practical challenges and expand their networks. Additionally, a long-term competition platform could be established to provide ongoing support, including seed funding, market promotion, and team development, assisting female entrepreneurs throughout the entire process, from startup to growth. The competition could focus on social enterprises, sustainable development, and female empowerment, encouraging women to propose innovative solutions to social issues such as women’s health, gender equality, or platforms supporting female entrepreneurs. This initiative would allow participants to showcase their entrepreneurial skills, connect with industry experts and investors, and increase their market opportunities, ultimately transforming their ideas into reality with the help of targeted prizes and professional guidance.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the impact of entrepreneurship education on female college students’ career choices within China, offering valuable insights for educational theory and practice. The findings highlight that courses and competitions are effective in fostering entrepreneurial intentions among female students, whereas practices and policies require further refinement.

The study advances theoretical discourse by integrating human capital and stereotype threat theories to clarify the gendered dimensions of educational impact. This approach enhances our understanding of how entrepreneurship education interacts with gender-specific factors, challenging conventional paradigms that may overlook the unique needs of female students. The large-scale empirical dataset from China further serves as a reference for cross-cultural comparisons, emphasizing the importance of contextualizing educational evaluations within specific socio-economic environments.

On a practical level, this research underscores the need for targeted educational reforms that address the distinct challenges faced by female students in entrepreneurship. It calls for more inclusive and adaptable curricula aligned with the digital landscape, better equipping female students to navigate entrepreneurial complexities. Additionally, it advocates for policies that support female entrepreneurship, recognizing that current frameworks may insufficiently address specific barriers faced by women [

64].

In sum, this study contributes to the broader field of educational evaluation, offering globally relevant recommendations for educators and policymakers. The findings encourage further research on the intersection of gender, education, and entrepreneurship, prompting a reevaluation of educational systems to promote equity and inclusion. As the digital era reshapes education, this research stands as a critical reference point for future assessments of entrepreneurship education and its role in advancing gender equity in entrepreneurial careers.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This study enhances understanding of the impact of entrepreneurship education on female students’ career choices, but some limitations remain. First, while the survey-based approach supports large-scale data collection, it limits exploration of specific causal mechanisms. Future studies could address this with qualitative or longitudinal methods. Second, this study focuses on four dimensions of entrepreneurship education—courses, competitions, practices, and policies. Expanding to include factors like mentorship, networking, and digital resources would provide a more comprehensive view. Addressing these areas will strengthen findings and further inform how entrepreneurship education can best support female students’ aspirations.

Author Contributions

S.S. drafted the initial version, clarified the conceptual logic, and wrote the paper. X.Z., L.Z., and Y.B. further supplemented, revised, and refined the content and language. L.Z., Y.B. are co-corresponding authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Major Project of Key Research Platforms for High-Quality Philosophy and Social Sciences in Zhejiang Province: “Research on Artificial Intelligence Empowering Innovation and Entrepreneurship Education” grant number 2025JDKT17Z.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All studies in this manuscript were approved by the ethics committee of the first author’s institution and were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (protocol number is 2023-12, and the date of approval is 15 December 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Consent from all research participants was obtained by virtue of survey completion.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be obtained on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Jackson, D.; Lambert, C.; Sibson, R.; Bridgstock, R.; Tofa, M. Student Employability-building Activities: Participation and Contribution to Graduate Outcomes. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 2024, 43, 1308–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, Y. Research on the Influencing Factors of Chinese College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention from the Perspective of Resource Endowment. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2023, 21, 100832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruparel, N.; Bhardwaj, S.; Seth, H.; Choubisa, R. Systematic Literature Review of Professional Social Media Platforms: Development of a Behavior Adoption Career Development Framework. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 156, 113482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakides, L.; Creemers, B.P.M.; Panayiotou, A.; Charalambous, E. Quality and Equity in Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GEM. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Global Report 2023/2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/51377 (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Henry, C.; Lewis, K. A Review of Entrepreneurship Education Research. Educ. Train. 2018, 60, 263–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowiński, W.; Haddoud, M.Y.; Lančarič, D.; Egerová, D.; Czeglédi, C. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Education, Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy and Gender on Entrepreneurial Intentions of University Students in the Visegrad Countries. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 44, 361–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chankseliani, M.; McCowan, T. Higher Education and the Sustainable Development Goals. High. Educ. 2020, 81, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebrahimi, R.; Choobchian, S.; Farhadian, H.; Goli, I.; Farmandeh, E.; Azadi, H. Investigating the Effect of Vocational Education and Training on Rural Women’s Empowerment. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahl, H. Why Research on Women Entrepreneurs Needs New Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2006, 30, 595–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullough, A.; Guelich, U.; Manolova, T.S.; Schjoedt, L. Women’s Entrepreneurship and Culture: Gender Role Expectations and Identities, Societal Culture, and the Entrepreneurial Environment. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 58, 985–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, N.A.; Ramadani, V.; Anggadwita, G.; Maulida, G.S.; Zuferi, R.; Maalaoui, A. Gender Stereotype Perception, Perceived Social Support and Self-efficacy in Increasing Women’s Entrepreneurial Intentions. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2023, 29, 1290–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, M.; Kaleem, N.; Chani, M.I.; Ahmed, M. Worldwide Role of Women Entrepreneurs in Economic Development. Asia Pac. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 14, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, V.; Van Praag, M. Mind the Gap: The Role of Gender in Entrepreneurial Career Choice and Social Influence by Founders. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 841–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiarena, A. How Gender Stereotypes Shape Venture Growth Expectations. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 58, 1015–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattner, F.; Sundermeier, J. Revision Needed? A Social Constructionist Perspective on Measurement Scales for Assessing Gender Role Stereotypes in Entrepreneurship. Int. Small Bus. J. Res. Entrep. 2023, 41, 825–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liñán, F.; Jaén, I.; Martín, D. Does Entrepreneurship Fit Her? Women Entrepreneurs, Gender-role Orientation, and Entrepreneurial Culture. Small Bus. Econ. 2020, 58, 1051–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rodríguez, I.; Quintana-Rojo, C.; Gento, P.; Callejas-Albinana, F.E. Public Policy Recommendations for Promoting Female Entrepreneurship in Europe. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 18, 1235–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C.G. Research on Women Business Owners: Past Trends, a New Perspective and Future Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 1992, 16, 5–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, L.; Henry, C.; Ahl, H.; Mikalsen, G.H. Women’s Entrepreneurship Policy Research: A 30-year Review of the Evidence. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 53, 409–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wang, J.; Long, Z.; Huang, Y. Improving the Entrepreneurial Competence of College Social Entrepreneurs: Digital Government Building, Entrepreneurship Education, and Entrepreneurial Cognition. Sustainability 2022, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Morais Santos, N.; Cottone, P.F.; Antloga, C.; Hochdorn, A.; Morais Carvalho, A.; Andrade Barbosa, M. Female Entrepreneurship in Brazil: How Scientific Literature Shapes the Sociocultural Construction of Gender Inequalities. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2022, 9, 360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, E.A.; Affum-Osei, E. Entrepreneurship as a Career Choice: The Impact of Locus of Control on Aspiring Entrepreneurs’ Opportunity Recognition. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 98, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Fonseca, J.G. Unemployment, Entrepreneurship and Firm Outcomes. Rev. Econ. Dyn. 2021, 45, 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Bennett, D.; Chen, S.-C. Perceived Organisational Support and University Students’ Career Exploration: The Mediation Role of Career Adaptability. Higher Educ. Res. Dev. 2022, 42, 903–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beeka, B.H.; Rimmington, M. Entrepreneurship as a Career Option for African Youths. J. Dev. Entrep. 2011, 16, 145–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Hughes, C. Chinese Women’s Entrepreneurial Career Choices: Exploring Factors. Career Dev. Int. 2024, 29, 770–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanea-Ivanovici, M.; Sarango-Lalangui, P.; Baber, H. Role of Entrepreneurial Education in Motivating Students to Take Entrepreneurship as a Career. In International Encyclopedia of Business Management Role of Entreprene; Elsevier eBooks; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.O. The Mediating Effects of Entrepreneurial Self-efficacy in the Relationship Between Entrepreneurship Education and Start-up Readiness. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, G.S. Investment in Human Capital: A Theoretical Analysis. J. Polit. Econ. 1962, 70, 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laspita, S.; Sitaridis, I.; Kitsios, F.; Sarri, K. Founder or Employee? The Effect of Social Factors and the Role of Entrepreneurship Education. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 155, 113422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, B.C.; McNally, J.J.; Kay, M.J. Examining the Formation of Human Capital in Entrepreneurship: A Meta-analysis of Entrepreneurship Education Outcomes. J. Bus. Ventur. 2012, 28, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, C.F.; Yáñez, D.; Santander, P. Do Universities Train Entrepreneurs? Rev. Actual. Investig. Educ. 2019, 20, 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Turban, D.B.; Wasti, S.A.; Sikdar, A. The Role of Gender Stereotypes in Perceptions of Entrepreneurs and Intentions to Become an Entrepreneur. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; An, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, P. The Role of Entrepreneurship Policy in College Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention: The Intermediary Role of Entrepreneurial Practice and Entrepreneurial Spirit. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 585698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-H.; Lin, H.-H.; Wang, Y.-M.; Wang, Y.-S.; Lo, C.-W. Investigating the Relationships Between Entrepreneurial Education and Self-efficacy and Performance in the Context of Internet Entrepreneurship. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.J. The Global Training Deficit: The Scarcity of Formal and Informal Professional Development Opportunities for Women Entrepreneurs. Ind. Commer. Train. 2012, 44, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.C.; Steele, C.M.; Gross, J.J. Signaling Threat. Psychol. Sci. 2007, 18, 879–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Sumettikoon, P. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis: An Innovative Female Entrepreneurship Education Ecosystem in China. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2023, 37, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Bu, Y.; Long, Z. Institutional Environment and College Students’ Entrepreneurial Willingness: A Comparative Study of Chinese Provinces Based on fsQCA. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, V.F.; Galina, S.V.R. Experiential Learning in Entrepreneurship Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2022, 121, 103919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick-Sagoe, C.; Lee, K.Y.; Boakye, A.O.; Mpuangnan, K.N.; Asare-Nuamah, P.; Dick-Sagoe, A.D. Facilitators of Tertiary Students’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: Insights for Lesotho’s National Entrepreneurship Policy. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A.; Gailly, B.; Lassas-Clerc, N. Assessing the Impact of Entrepreneurship Education Programmes: A New Methodology. J. Eur. Ind. Train. 2006, 30, 701–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Z.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhou, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, Z. Research on the Drivers of Entrepreneurship Education Performance of Medical Students in the Digital Age. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 733301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, S.M.; Khan, E.A.; Nabi, M.N.U. Entrepreneurial Education at University Level and Entrepreneurship Development. Educ. Train. 2017, 59, 888–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Li, N.; Li, K.; Li, P.; Huang, L.; Huang, Y. The Impact of Entrepreneurship Competitions on Entrepreneurial Competence of Chinese College Students. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 784225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arranz, N.; Ubierna, F.; Arroyabe, M.F.; Perez, C.; Fdez De Arroyabe, J.C. The Effect of Curricular and Extracurricular Activities on University Students’ Entrepreneurial Intention and Competences. Stud. High. Educ. 2016, 42, 1979–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, N.A.; Verduijn, K.; Gartner, W.B. Entrepreneurship-as-practice: Grounding Contemporary Theories of Practice Into Entrepreneurship Studies. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 3, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Gelderen, M. Developing Entrepreneurial Competencies Through Deliberate Practice. Educ. Train. 2022, 65, 530–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, A.; Li, A.; Utami, W.; Sumaji, Y. The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Education Programs in Indonesian Higher Education Institutions. Entrep. Educ. 2022, 5, 289–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, L.M.; Schroeter, C.; Wright, C. Lighting the Flame of Entrepreneurship Among Agribusiness Students. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 21, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschning, R.; Mrożewski, M. The Role of Entrepreneurial Absorptive Capacity for Knowledge Spillover Entrepreneurship. Small Bus. Econ. 2022, 60, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, D.; Minola, T.; Eddleston, K.A. How Do Scientists Contribute to the Performance of Innovative Start-ups? An Imprinting Perspective on Open Innovation. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 56, 895–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, B.; Babin, B.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral Collinearity and Misleading Results in Variance-Based SEM: An Illustration and Recommendations. J. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2012, 13, 546–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, S.; Daniel, A.D.; Botelho, A. The Effect of Entrepreneurship Education on the Determinants of Entrepreneurial Behaviour Among Higher Education Students: A Multi-group Analysis. J. Innov. Knowl. 2023, 8, 100324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousaf, H.Q.; Munawar, S.; Ahmed, M.; Rehman, S. The Effect of Entrepreneurial Education on Entrepreneurial Intention: The Moderating Role of Culture. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 20, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägg, G.; Politis, D.; Alsos, G.A. Does Gender Balance in Entrepreneurship Education Make a Difference to Prospective Start-up Behaviour? Educ. Train. 2022, 65, 630–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, V.M.; Chatterji, A.K. The Entrepreneurial Process: Evidence From a Nationally Representative Survey. Strateg. Manag. J. 2019, 44, 86–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D.A.; Souitaris, V.; Gruber, M. Creating New Ventures: A Review and Research Agenda. J. Manag. 2020, 47, 11–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Q.D.; Nguyen, H.T. Entrepreneurship Education and Entrepreneurial Intention: The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Capacity. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2022, 21, 100730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadani, V.; Rahman, M.M.; Salamzadeh, A.; Rahaman, M.S.; Abazi-Alili, H. Entrepreneurship Education and Graduates’ Entrepreneurial Intentions: Does Gender Matter? A Multi-Group Analysis Using AMOS. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 180, 121693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, S.N.; Razzaq, K.; Imam, H. How Does Action-oriented Personality Traits Impact on Entrepreneurial Career Choices? A Trait-factor Theory Perspective. Kybernetes 2022, 52, 5068–5086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zhao, G.; Long, Z.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Z. Entrepreneurship or Employment? A Survey of College Students’ Sustainable Entrepreneurial Intentions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).