Short Food Supply Chain Status and Pathway in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How have SFSCs been conceptualised and implemented in Africa relative to their stated objectives?

- What are the main thematic domains in African SFSC research, and how do they interrelate?

- What gaps and opportunities exist for institutionalising SFSCs in the food systems in Africa?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Publication Statistics

2.3. Data Classification

2.4. Coding and Thematic Matrix Construction

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Literature Overview

3.1.1. Publication Trends over Time

3.1.2. Publishing Landscape

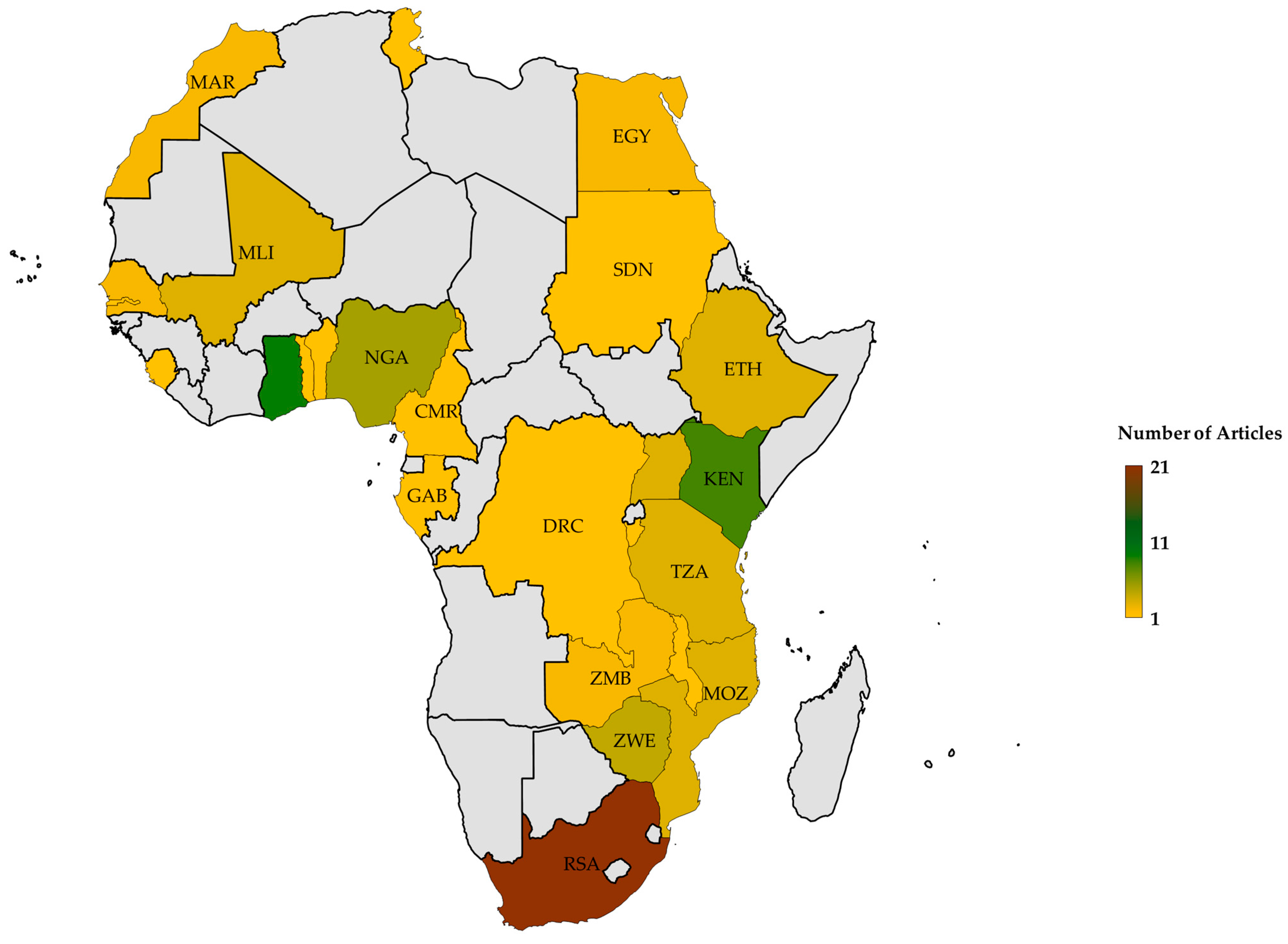

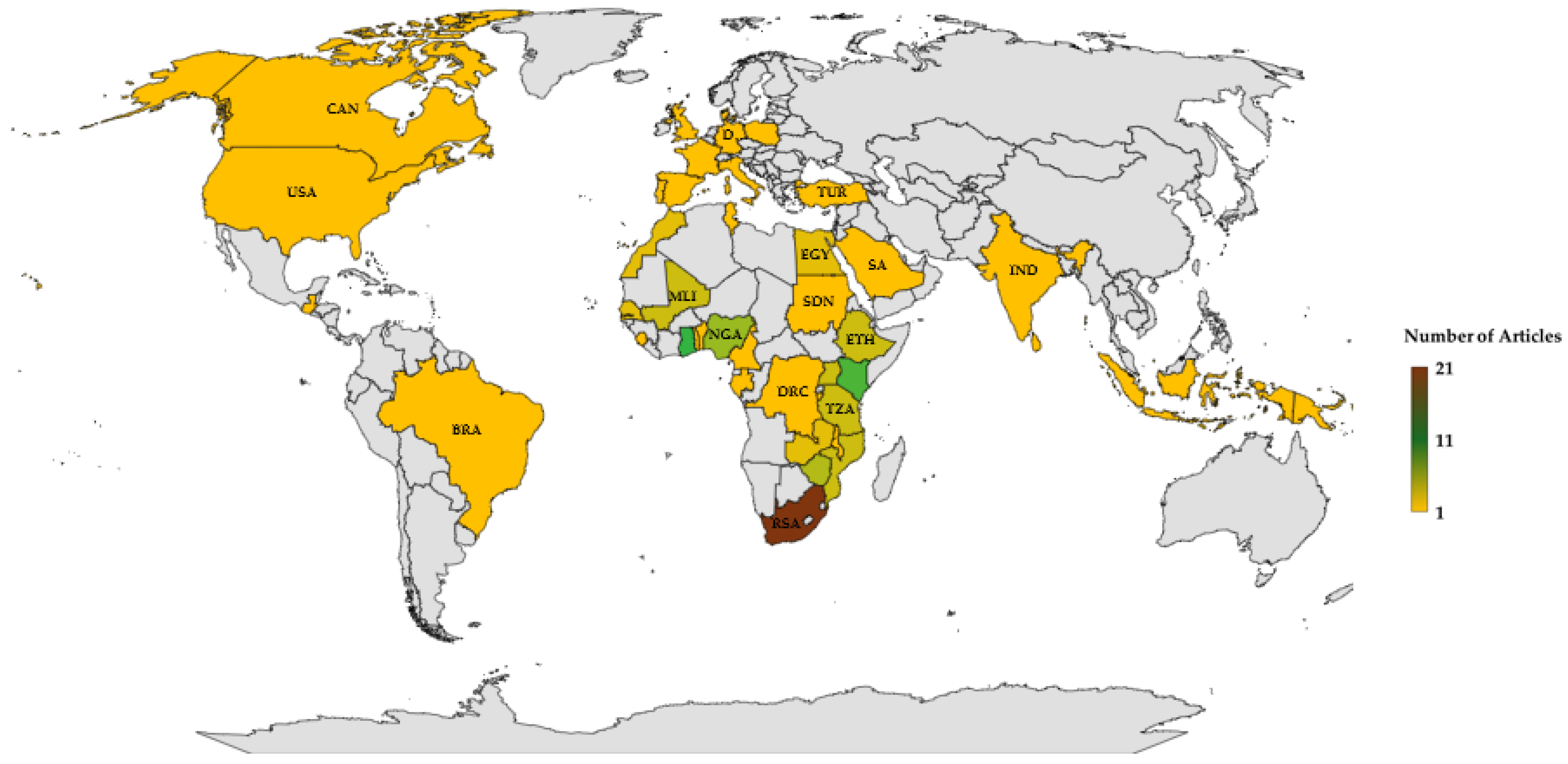

3.1.3. Geographic Distribution of Research

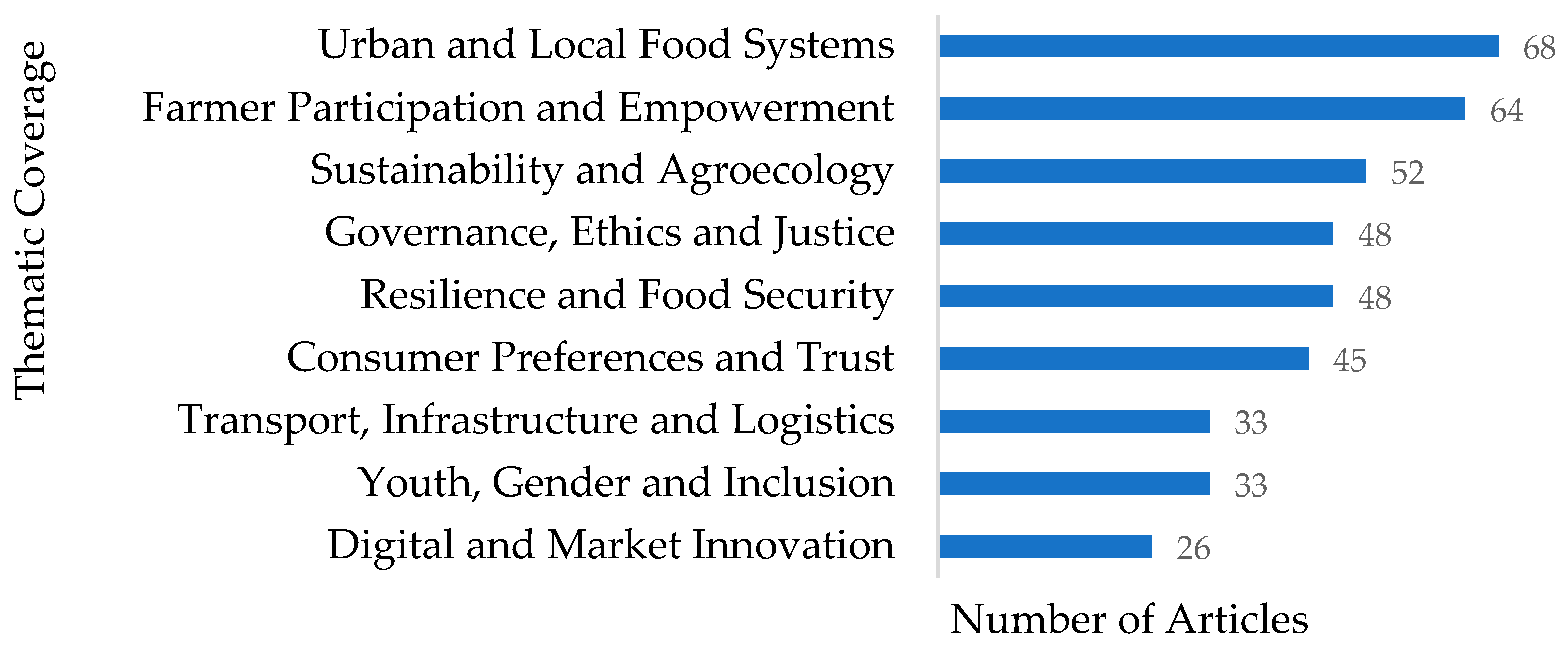

3.2. Thematic Overview

3.2.1. Governance, Resilience, and Sustainability

3.2.2. Urbanisation and Participation

3.2.3. Innovation and Logistics

3.2.4. Inclusion and Equity

3.3. Thematic Relevance to Food Supply Chains in Africa

4. Discussion

4.1. SFSC Conceptualisation and Implementation in Africa

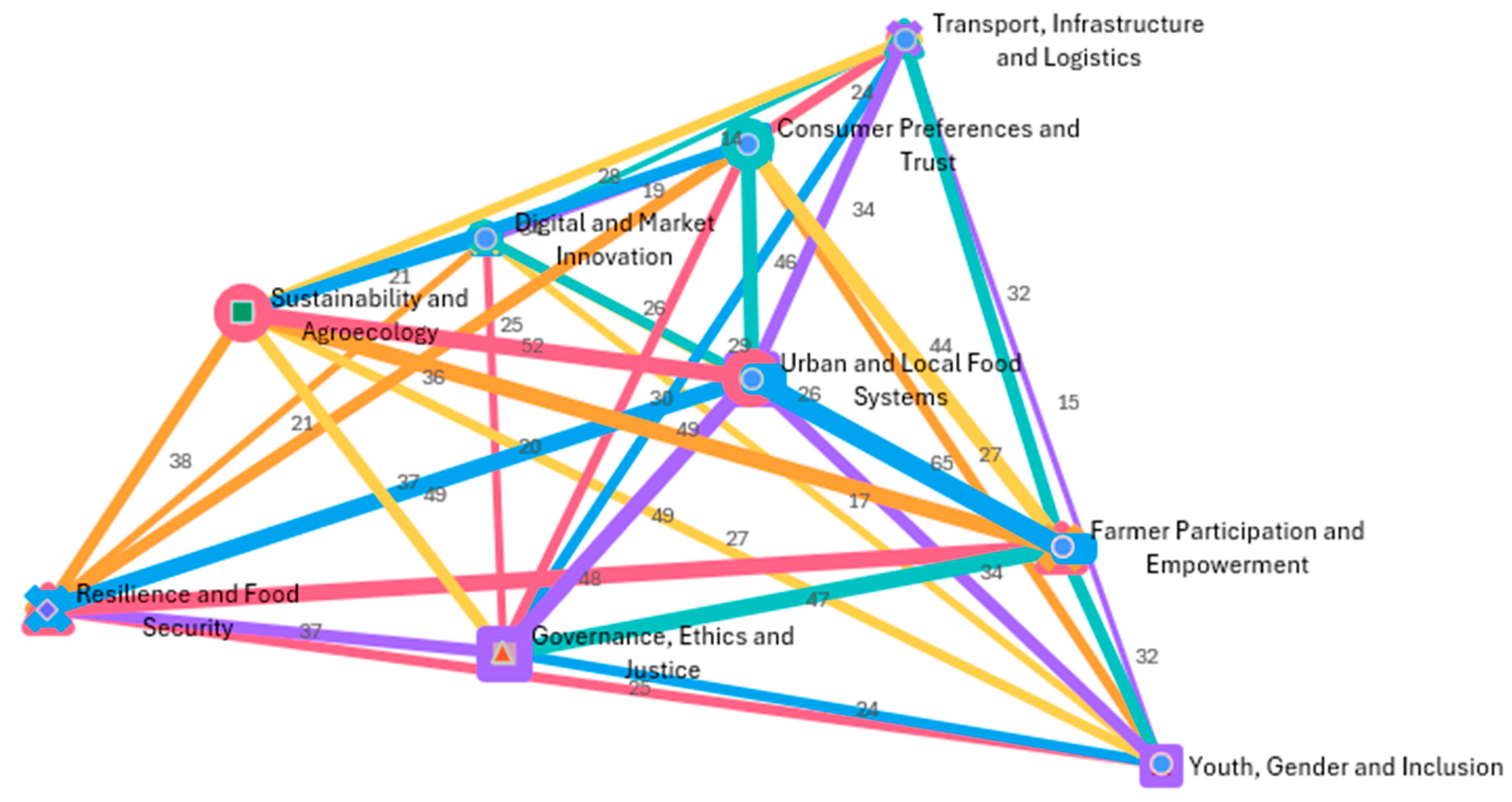

4.2. Thematic Domains in African SFSC Research and Their Interrelations

4.3. Gaps, Contradictions, and Institutionalisation Opportunities for SFSCs in Food Systems

4.4. Theoretical Implications

4.5. Practical Implications

4.6. Policy Implications

4.7. Limitations

4.8. Directions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Database | String |

|---|---|

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“short food supply chain*” OR “local food system*” OR “local food network*” OR “alternative food network*” OR “community supported agriculture”) |

| Web of Science | (“short food supply chain*” OR “local food system*” OR “local food network*” OR “alternative food network*” OR “community supported agriculture”) AND (Africa) |

| EBSCOHost | (TI “short food supply chain*” OR AB “short food supply chain*” OR SU “short food supply chain*” OR TI “local food system*” OR AB “local food system*” OR SU “local food system*” OR TI “local food network*” OR AB “local food network*” OR SU “local food network*” OR TI “alternative food network*” OR AB “alternative food network*” OR SU “alternative food network*” OR TI “community supported agriculture” OR AB “community supported agriculture” OR SU “community supported agriculture”) AND (TI Africa OR AB Africa OR SU Africa) |

| Article Details | Database | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Sowunmi, F. A. & Adeduntan, F. L. (2020). Impact of Rural-Urban Migration on the Food Consumption Pattern of Farming Households in Ibadan/Ibarapa Agricultural Zone of Oyo State, Nigeria. In A. Obayelu & O. Obayelu (Eds.), Developing Sustainable Food Systems, Policies, and Securities (pp. 216–238). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-2599-9.ch013 | SCOPUS | Not available through the institution’s database subscription |

| Sowunmi, F. A. & Adeduntan, F. L. (2022). Impact of Rural-Urban Migration on the Food Consumption Pattern of Farming Households in Ibadan/Ibarapa Agricultural Zone of Oyo State, Nigeria. In I. Management Association (Ed.), Research Anthology on Strategies for Achieving Agricultural Sustainability (pp. 1130–1153). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-6684-5352-0.ch060 | SCOPUS | Not available through the institution’s database subscription |

| Shava, E. (2022). Survival of African Governments in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. In: Benyera, E. (eds) Africa and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Advances in African Economic, Social and Political Development. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-87524-4_7 | SCOPUS | Not available through the institution’s database subscription |

| Ndhlovu, E., Mhlanga, D. (2024). Towards a Functional Food System in Africa. In: Mhlanga, D., Ndhlovu, E. (eds) The Russia-Ukraine Conflict and Development in Africa. Contributions to Political Science. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-63333-1_21 | SCOPUS | Not available through the institution’s database subscription |

| Lamanna, C., Namoi, N., Kimaro, A.A. et al. (2016). Evidence-based opportunities for out-scaling climate-smart agriculture in East Africa | AGRIS | View and download link not found. |

| Kanosvamhira, T.P. (2021). Urban Agriculture and the Organisation of Urban Farmers in African Cities: The Experiences of Cape Town and Dar es Salaam. In: Halberstadt, J., Marx Gómez, J., Greyling, J., Mufeti, T.K., Faasch, H. (eds) Resilience, Entrepreneurship and ICT. CSR, Sustainability, Ethics & Governance. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-78941-1_10 | SpringerLink | Not available through the institution’s database subscription |

| Theme | Determinant Terms | Authors |

|---|---|---|

| Urban and Local Food Systems | city, community, local, local food, neighbourhood, proximity, short supply, urban | [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

| Farmer Participation and Empowerment | agency, collaboration, cooperation, decision-making, empowerment, engagement, farmer, inclusion, initiative, involvement, leadership, participation, representation, voice | [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,49,51,52,53,56,57,58,59,60,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,86,87,88,89,90,91,92] |

| Sustainability and Agroecology | agroecology, biodiversity, conservation, ecological, environment, organic, soil, sustainability | [26,28,30,31,32,33,34,35,37,38,39,41,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,60,64,66,67,68,70,71,72,73,74,76,80,84,86,87,88,89,90] |

| Governance, Ethics and Justice | accountability, ethics, governance, institution, justice, policy, regulation, rights | [26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,42,43,44,45,46,49,50,51,52,53,54,58,61,62,63,64,66,68,70,71,72,74,75,78,79,80,81,82,83,86,87,93] |

| Resilience and Food Security | availability, crisis, food security, nutrition, resilience, shock, stability, vulnerability | [27,28,29,30,31,33,34,36,37,38,39,44,45,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,58,60,62,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,72,74,76,78,80,82,83,84,85,86,88,89] |

| Consumer Preferences and Trust | awareness, behaviour, confidence, consumer, demand, perception, preference, trust | [27,28,30,31,34,36,37,40,43,44,45,46,47,49,51,52,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,64,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,79,80,83,85,86,88,90,92] |

| Infrastructure and Logistics | delivery, distribution, facilities, infrastructure, logistics, storage, supply chain, transport | [28,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,43,44,45,46,48,49,50,51,52,54,59,62,63,72,74,75,77,81,82,83,84,88,90] |

| Youth, Gender and Inclusion | empowerment, equity, gender, inclusion, inequality, marginalised, women, youth | [26,27,28,31,33,34,38,42,44,49,50,51,52,55,56,58,60,61,64,65,66,68,72,74,75,76,83,86,90,92] |

| Digital and Market Innovation | digital, information, innovation, market, platform, technology | [27,28,29,31,34,42,49,52,53,59,60,63,64,67,68,69,71,72,74,75,76,82,83,87,90,94] |

References

- Fanzo, J.; Bellows, A.L.; Spiker, M.L.; Thorne-Lyman, A.L.; Bloem, M.W. The Importance of Food Systems and the Environment for Nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 113, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.G.; Chavez-Santoscoy, R.A.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Agro-Food Systems and Environment: Sustaining the Unsustainable. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 31, 100413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, Q.; Fanzo, J.; Barrett, C.B.; Jones, A.D.; Herforth, A.; McLaren, R. Building a Global Food Systems Typology: A New Tool for Reducing Complexity in Food Systems Analysis. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 746512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts-Davies, S.; Barrett, J.; Brockway, P.; Norman, J. Is All Inequality Reduction Equal? Understanding Motivations and Mechanisms for Socio-Economic Inequality Reduction in Economic Narratives of Climate Change Mitigation. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 107, 103349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méjean, A.; Collins-Sowah, P.; Guivarch, C.; Piontek, F.; Soergel, B.; Taconet, N. Climate Change Impacts Increase Economic Inequality: Evidence from a Systematic Literature Review. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laar, A.; Tagwireyi, J.; Hassan-Wassef, H. From Dialogues to Action: Commitments by African Governments to Transform Their Food Systems and Assure Sustainable Healthy Diets. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 65, 101380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaker, T.; Meng, Q. Urban Disparity Analytics Using GIS: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazvinei Vhumbunu, C. Staple Crops Processing Zones, Food Security and Restoration of Local Food Systems in Zimbabwe. Afr. Dev. 2022, 47, 197–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, R.E.; Keane, C.R.; Burke, J.G. Disparities and Access to Healthy Food in the United States: A Review of Food Deserts Literature. Health Place 2010, 16, 876–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilar-Compte, M.; Burrola-Mendez, S.; Lozano-Marrufo, A.; Ferre-Eguiluz, I.; Flores, D.; Gaitan-Rossi, P.; Teruel, G.; Perez-Escamilla, R. Urban Poverty and Nutrition Challenges Associated with Accessibility to a Healthy Diet: A Global Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Equity Health 2021, 20, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, G.; Reis, K.; Desha, C.; Burkett, I. Valuing Farmers in Transitions to More Sustainable Food Systems: A Systematic Literature Review of Local Food Producers’ Experiences and Contributions in Short Food Supply Chains. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 42, 565–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapari, M.; Hlophe-Ginindza, S.; Nhamo, L.; Mpandeli, S. Contribution of Smallholder Farmers to Food Security and Opportunities for Resilient Farming Systems. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1149854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P.; de Labarre, M.D.; Lecoeur, J.-L.; Maj, A.; Majewski, E.; et al. Short Food Supply Chains and Their Contributions to Sustainability: Participants’ Views and Perceptions from 12 European Cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, T.G.; Davids, Y.D.; Rule, S.; Tirivanhu, P.; Mtyingizane, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic Reveals an Unprecedented Rise in Hunger: The South African Government Was Ill-Prepared to Meet the Challenge. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manfouo, N.C.F. Monitoring Commercial and Smallholder Production Inequalities During South Africa’s Lockdown Using Remotely Sensed Data. Agrosystems Geosci. Environ. 2024, 7, e20460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misselhorn, A.; Hendriks, S.L. A Systematic Review of Sub-National Food Insecurity Research in South Africa: Missed Opportunities for Policy Insights. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, M.; Charatsari, C.; Lioutas, E.D.; Vecchio, Y.; Masi, M. Staging Value Creation Processes in Short Food Supply Chains of Italy. Agric. Food Econ. 2024, 12, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Diarrassouba, I.; Joncour, C.; Michel Loyal, S. Optimization and Analysis of the Impact of Food Hub Location on GHG Emissions in a Short Food Supply Chain. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charatsari, C.; Kitsios, F.; Lioutas, E.D. Short Food Supply Chains: The Link Between Participation and Farmers’ Competencies. Renew. Agric. Food Syst. 2019, 35, 643–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feurich, M.; Kourilova, J.; Pelucha, M.; Kasabov, E. Bridging the Urban–Rural Digital Divide: Taxonomy of Best Practice and Critical Reflection on the EU Countries’ Approach. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2023, 32, 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deka, N.; Goswami, K. Analysing Alternative Food Networks in Highly-Globalised and Standardised Agrifood Systems to Attain Sustainability for Small-Scale Growers: Inferences from the Tea Sector. Local Environ. 2024, 29, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Mohammed, R.A.; Nashwan, A.J.; Ibrahim, R.H.; Abdalla, A.Q.; Ameen, B.M.M.; Khdhir, R.M. Using Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2025, 6, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W.; Howell, K.; Ranfagni, S. A Step-by-Step Process of Thematic Analysis to Develop a Conceptual Model in Qualitative Research. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 5789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel-Villarreal, R.; Vilalta-Perdomo, E.; Hingley, M.; Canavari, M. Rethinking Alternative Food Networks: Unpacking Key Attributes and Overlapping Concepts. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 49, 415–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musazura, W.; Odindo, A.O. Characterisation of Selected Human Excreta-Derived Fertilisers for Agricultural Use: A Scoping Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganini, N.; Lemke, S. “There Is Food We Deserve, and There Is Food We Do Not Deserve”: Food Injustice, Place, and Power in Urban Agriculture in Cape Town and Maputo. Local Environ. 2020, 25, 1000–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakimi, F.; Sehli, S.; Hashem, A.; Avila-Quezada, G.D.; Abd_Allah, E.F. Comparative Analysis of Organic and Conventional Farm Sustainability in Peri-Urban Zones of Rabat, Morocco: Insights and Perspectives. Cogent Food Agric. 2025, 11, 2463562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malan, N. Urban Farmers and Urban Agriculture in Johannesburg: Responding to the Food Resilience Strategy. Agrekon 2015, 54, 51–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvany, P.; Murphy, B. Sustaining Local Food Webs: Insights from Kenya and the UK. Food Chain 2015, 5, 181–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchanji, E.B.; Lutomia, C.K. Regional Impact of COVID-19 on the Production and Food Security of Common Bean Smallholder Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa: Implication for SDGs. Glob. Food Sec. 2021, 29, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olumba, C.C.; Olumba, C.N.; Alimba, J.O. Constraints to Urban Agriculture in Southeast Nigeria. Hum. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenkamp, J.; Cilliers, E.J.; Cilliers, S.S.; Lategan, L. Food for Thought: Addressing Urban Food Security Risks through Urban Agriculture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinarwo, J. Strengthening Local Food Systems in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic: Lessons from Zimbabwe. In COVID-19 in Zimbabwe; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Antwi-Agyei, P.; Atta-Aidoo, J.; Asare-Nuamah, P.; Stringer, L.C.; Antwi, K. Trade-Offs, Synergies and Acceptability of Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices by Smallholder Farmers in Rural Ghana. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2023, 21, 2193439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlos Bezerra, J.; Nqowana, T.; Oosthuizen, R.; Canca, M.; Nkwinti, N.; Mantel, S.K.; New, M.; Ford, J.; Zavaleta-Cortijo, C.C.; Galappaththi, E.K.; et al. Addressing Food Insecurity Through Community Kitchens During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study from the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidberg, S.; Goldstein, L. Alternative Food in the Global South: Reflections on a Direct Marketing Initiative in Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 2011, 27, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, C.; Karriem, A. Harnessing Public Food Procurement for Sustainable Rural Livelihoods in South Africa through the National School Nutrition Programme: A Qualitative Assessment of Contributions and Challenges. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhovi, S.M.; Kiteme, B.; Mwangi, J.; Wambugu, G. Transdisciplinary Knowledge Co-Production as a Catalyst for Community-Led Innovation: A Case Study of Farmers’ Milk Cooperative in Laikipia, Kenya. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2024, 8, 1494692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalubowa, W.; Moruzzo, R.; Scarpellini, P.; Granai, G. The Potential of Farmers’ Markets: The Uganda Case. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, E.; Binns, T.; Bek, D. ‘Alternative Foods’ and Community-Based Development: Rooibos Tea Production in South Africa’s West Coast Mountains. Appl. Geogr. 2007, 27, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odame, H.S.; Okeyo-Owuor, J.B.; Changeh, J.G.; Otieno, J.O. The Role of Technology in Inclusive Innovation of Urban Agriculture. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 43, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmann, G.F.; King, R.P. Research on Agri-Food Supply Chains in Southern Africa Involving Small-Scale Farmers: Current Status and Future Possibilities. Agrekon 2010, 49, 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Drimie, S.; Zgambo, O.; Biggs, R. Planning for Change: Transformation Labs for an Alternative Food System in Cape Town, South Africa. Urban Transform. 2020, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doernberg, A.; Piorr, A.; Zasada, I.; Wascher, D.; Schmutz, U. Sustainability Assessment of Short Food Supply Chains (SFSC): Developing and Testing a Rapid Assessment Tool in One African and Three European City Regions. Agric. Hum. Values 2022, 39, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Azazz, A.M.S.; Hassan, S.S.; Fayyad, S. Farm-to-Fork and Sustainable Agriculture Practices: Perceived Economic Benefit as a Moderator and Environmental Sustainability as a Mediator. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Góralska-Walczak, R.; Stefanovic, L.; Kopczynska, K.; Kazimierczak, R.; Bugel, S.G.; Strassner, C.; Peronti, B.; Lafram, A.; El Bilali, H.; Srednicka-Tober, D. Entry Points, Barriers, and Drivers of Transformation Toward Sustainable Organic Food Systems in Five Case Territories in Europe and North Africa. Nutrients 2025, 17, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz Torres, M.J.; Fernández-Izquierdo, M.Á.; Ferrero-Ferrero, I.; Escrig-Olmedo, E.; Rivera-Lirio, J.M. Transitioning the Agri-Food System: Does Closeness Mean Sustainability? How Production and Shipping Strategies Impact Socially and Environmentally—Comparing Spain, South Africa, and U.S. Citrus Fruit Productions. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 540–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boillat, S.; Bottazzi, P.; Sabaly, I.K. The Division of Work in Senegalese Conventional and Alternative Food Networks: A Contributive Justice Perspective. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1127593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanosvamhira, T.P. Beyond the Blueprint: Rethinking Governance and Sustainability in Cape Town’s Community Gardens. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesselman, B. Transforming South Africa’s Unjust Food System: An Argument for Decolonisation. Food Cult. Soc. 2023, 27, 792–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutcliffe, S.; Lau, J.; Barnes, M.; Mbaru, E.; Wade, E.; Hungito, W.; Muly, I.; Wanyonyi, S.; Muthiga, N.; Cohen, P.; et al. COVID-19 Impacts on Food Systems in Fisheries-Dependent Island Communities. Ecol. Soc. 2023, 28, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murungweni, C.; van Wijk, M.T.; Giller, K.E.; Andersson, J.A.; Smaling, E.M.A. Adaptive Livelihood Strategies Employed by Farmers to Close the Food Gap in Semi-Arid South Eastern Zimbabwe. Food Secur. 2014, 6, 313–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odozi, J.C. Dynamic Food Insecurity and Resilience of Smallholder Households in a Local Food System: The Pandemic Experience in Nigeria. Int. J. Food Sci. Agric. 2022, 6, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tora, T.T. Production Preference Barriers and Lowland-Appropriate Strategies of Sustaining Local Food Systems in Drought-Affected Southern Ethiopia. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannor, R.K.; Oppong-Kyeremeh, H.; Boateng, A.O.; Bold, E.; Gruzah, B. Short Supply Chain Choice and Impact Amongst Rice Processors in Rural Ghana. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 15, 150–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bannor, R.K.; Boateng, A.O.; Oppong-Kyeremeh, H.; Bold, E. Direct, Indirect and Mediation Effects of Consumer Ethnocentrism on the Willingness to Pay Premium Price for Locally Produced Honey. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2024, 37, 296–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borelli, T.; Hunter, D.; Padulosi, S.; Amaya, N.; Meldrum, G.; Beltrame, D.M.d.O.; Samarasinghe, G.; Wasike, V.W.; Güner, B.; Tan, A.; et al. Local Solutions for Sustainable Food Systems: The Contribution of Orphan Crops and Wild Edible Species. Agronomy 2020, 10, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabagou, M.; Kpotchou, K. Analysis of Household Food Procurement Practices from a Sustainability Perspective in Grand Lomé, Togo. Edelweiss Appl. Sci. Technol. 2024, 8, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noort, M.W.J.; Renzetti, S.; Linderhof, V.; du Rand, G.E.; Marx-Pienaar, N.; de Kock, H.L.; Magano, N.; Taylor, J.R.N. Towards Sustainable Shifts to Healthy Diets and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa with Climate-Resilient Crops in Bread-Type Products: A Food System Analysis. Foods 2022, 11, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, H.A.M.; Adam, Y.O.; Donkor, E.; Mithöfer, D. Consumers Behavior, Attitudes, and Beliefs Regarding Baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) Fruit and Pulp Consumption in Sudan. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1118714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, V. Food Security and Food Sovereignty in West Africa. Afr. Geogr. Rev. 2018, 37, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sithole, S.T.; Tevera, D.; Dinbabo, M.F. Feeding Hope: Zimbabwean Migrants in South Africa and the Evolving Landscape of Cross-Border Remittances. Glob. Food Secur. 2025, 44, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asante, I.S.; Aidoo, M.; Prah, S.; Sam Hagan, M.A.; Sackey, C.K. Achieving Food Security: Household Perception and Adoption of Home Gardening Techniques in Ghana. J. Agric. Food Res. 2024, 18, 101329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng, E.; Desczka, S.; Tsvetkov, B.; Kumar, I.; Galema, S. Rapid Co-Creative Assessment for Actionable Circular Food Systems. J. Agric. Food. Syst. Community. Dev. 2025, 14, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, J.; Losch, B.; Pereira, L.M. NUS So Fast: The Social and Ecological Implications of a Rapidly Developing Indigenous Food Economy in the Cape Town Area. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojang, B.; Emang, D. Can Cashew Value Chain Industry Improve Food Security: An Empirical Study from The Gambia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, L.M.; Schinko, T.; Sendzimir, J.; Mohammed, A.-R.; Buwah, R.; Vihinen, H.; Raymond, C.M. Interlinkages Between Leverage Points for Strengthening Adaptive Capacity to Climate Change. Sustain. Sci. 2023, 18, 2199–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zivhave, M.; Kornienko, K. Urban Agriculture’s ‘Invisible’ Short Food Value Chain: How Small-scale Farming Contributes to Johannesburg Food Security. Urban Forum 2024, 36, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanosvamhira, T.P. Cultivating Food Justice: Redefining Harvest Sales for Sustainable Urban Agriculture in Low-Income Cape Town Post COVID-19. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2024, 48, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.M.; Kushitor, S.B.; Cramer, C.; Drimie, S.; Isaacs, M.; Malgas, R.; Phiri, E.; Tembo, C.; Willis, J. Leveraging the Potential of Wild Food for Healthy, Sustainable, and Equitable Local Food Systems: Learning from a Transformation Lab in the Western Cape Region. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nchanji, E.B.; Lutomia, C.K. COVID-19 Challenges to Sustainable Food Production and Consumption: Future Lessons for Food Systems in Eastern and Southern Africa from a Gender Lens. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 27, 2208–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berg, H.; Mearns, K. An Exploration of Guesthouse Fresh Produce Purchasing Behaviour and Supply Chains in Johannesburg. J. Transp. Supply Chain. Manag. 2021, 15, a557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganini, N.; Adinata, K.; Buthelezi, N.; Harris, D.; Lemke, S.; Luis, A.; Koppelin, J.; Karriem, A.; Ncube, F.; Nervi Aguirre, E.; et al. Growing and Eating Food during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Farmers’ Perspectives on Local Food System Resilience to Shocks in Southern Africa and Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongnaa, C.A.; Ansah, R.O.; Akutinga, S.; Azumah, S.B.; Acheampong, R.; Nana, S.Y.; Mensah, G.A.; Gidisu, S.; Awunyo-Vitor, D. Profitability, Market Outlets and Constraints to Ghana’s Pig Production. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2023, 6, 100068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struik, P.C.; Klerkx, L.; Hounkonnou, D. Unravelling Institutional Determinants Affecting Change in Agriculture in West Africa. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2014, 12, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, A.C.; Hendriks, S.L. Does Food Assistance Improve Recipients’ Dietary Diversity and Food Quality in Mozambique? Agrekon 2017, 56, 248–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oloko, M.; Ekpo, R. Effects of the COVID-19 Lockdown on the Livelihood and Food Security of Street Food Vendors and Consumers in Nigeria. J. Afr. Stud. Dev. 2021, 13, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, S.E.; Lewis, D.; Travis, A.J. Small-Scale Egg Production Centres Increase Children’s Egg Consumption in Rural Zambia. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018, 14 (Suppl. 3), e12662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakariah-Akoto, S.; Armar-Klemesu, M.; Ankomah, A.; Torpey, K.; Aryeetey, R. Socio-Cultural Norms in the Local Food System and Potential Implications for Women’s Dietary Quality in Rural Northern Ghana. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2024, 24, 25052–25077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröger, K.; Lelea, M.A.; Hensel, O.; Kaufmann, B. Re-Framing Post-Harvest Losses Through a Situated Analysis of the Pineapple Value Chain in Uganda. Geoforum 2020, 111, 48–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanel, T.; Miller, B.; Aboul-Enein, B.; Benajiba, N.; Kruk, J. Farm-to-School Nutrition Programs with Special Reference to Egypt and Morocco. North. Afr. J. Food Nutr. Res. 2021, 5, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haysom, G. Food and the City: Urban Scale Food System Governance. Urban Forum 2015, 26, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. Rwanda Market in Addis Ababa: Between Chinese Migrants and a Local Food Network. China Perspect. 2019, 2019, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussayn, J.A.; Gulak, D.M. Realising Sustainable Food Systems Among Organic Farmers in Nigeria: Evidence from Community Supported Agriculture. Sci. Pap. Ser.—Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2020, 20, 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kesselman, B. The Contribution of Community Food Gardens to Food Sovereignty in Johannesburg, South Africa: A Look at Localisation and Democratisation. In Envisioning a Future Without Food Waste and Food Poverty: Societal Challenges; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 323–329. [Google Scholar]

- Mokoena, O.P.; Ntuli, T.S.; Ramarumo, T.; Seeletse, S.M. Applying the Analytic Hierarchy Process and Thematic Content Analysis to Assess Sustainability Among Small-Scale Dairy Farmers. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmann, G.; Grimm, D.; Kuenz, A.; Hessel, E. Combining Land-Based Organic and Landless Food Production: A Concept for a Circular and Sustainable Food Chain for Africa in 2100. Org. Agric. 2019, 10, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapinski, M.; Raymond, R.; Davy, D.; Herrmann, T.; Bedell, J.-P.; Ka, A.; Odonne, G.; Chanteloup, L.; Lopez, P.J.; Foulquier, É.; et al. Local Food Systems under Global Influence: The Case of Food, Health and Environment in Five Socio-Ecosystems. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souissi, A.; Dhehibi, B.; Oumer, A.M.; Mejri, R.; Frija, A.; Zlaoui, M.; Dhraief, M.Z. Linking Farmers’ Perceptions and Management Decision Toward Sustainable Agroecological Transition: Evidence from Rural Tunisia. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1389007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, A.; Conradie, B. Urban Agriculture’s Enterprise Potential: Exploring Vegetable Box Schemes in Cape Town. Agrekon 2013, 52 (Suppl. 1), 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, X.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Z.; Kang, X.; Yang, Z. Exploring Community-Supported Agriculture through Maslow’s Hierarchy: A Systematic Review of Research Themes and Trends. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegerif, M.C.A.; Martucci, R. Milk and the City: Raw Milk Challenging the Value Claims of Value Chains. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2018, 43, 1077–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dentoni, D.; Bijman, J.; Bossle, M.B.; Gondwe, S.; Isubikalu, P.; Ji, C.; Kella, C.; Pascucci, S.; Royer, A.; Vieira, L. New Organizational Forms in Emerging Economies: Bridging the Gap Between Agribusiness Management and International Development. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

| Language | Peer-reviewed articles published in English. | Articles published in languages other than English or without an available English translation. |

| Publication Period | Studies published up to 31 May 2025. | None. |

| Research Focus | Studies with a strong or partial link to SFSCs. Partial links must explicitly demonstrate relevance to one or more SFSC attributes (e.g., proximity, sustainability, direct producer-consumer relationships). | Studies that lacked a clear or demonstrable connection to SFSCs or their defining attributes. |

| Food Systems and Activities | Research addressing food security, sustainable food practices, or related activities where SFSCs have a demonstrable or potential role. | Studies focused exclusively on industrial or globalised food supply chains without relevance to SFSCs or local food systems. |

| Geographical Location | Studies conducted in African countries, with a focus on SFSCs. | Research focused on SFSCs outside Africa. |

| Publisher | Scopus Ranking | Total | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability | Q1 | 7 | 10% |

| Agrekon | Q2 | 4 | 6% |

| Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems | Q1 | 3 | 4% |

| Journal of Agribusiness in Developing and Emerging Economies | Q1 | 3 | 4% |

| Sustainability Science | Q1 | 3 | 4% |

| Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems | Q1 | 2 | 3% |

| Global Food Security | Q1 | 2 | 3% |

| International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability | Q1 | 2 | 3% |

| Urban Forum | Q2 | 2 | 3% |

| African Geographical Review | Q3 | 1 | 1% |

| African Journal of Food, Agriculture, Nutrition and Development | Not ranked | 1 | 1% |

| Agriculture | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Agriculture and Human Values | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Agronomy | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Applied Geography | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| China Perspectives | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Cogent Food & Agriculture | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Discover Sustainability | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Ecology and Society | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Edelweiss Applied Science and Technology | Q3 | 1 | 1% |

| Food Chain | Not ranked | 1 | 1% |

| Food Security | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Food, Culture & Society | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Foods | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Frontiers in Nutrition | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Geoforum | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Humanities and Social Sciences Communications | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| International Journal of Food Science and Agriculture | Not ranked | 1 | 1% |

| International Journal of Urban and Regional Research | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of African Studies and Development | Not ranked | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of Agriculture and Food Research | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of Cleaner Production | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of International Food & Agribusiness Marketing | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of Rural Studies | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of Transport and Supply Chain Management | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Journal of Urban Affairs | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Local Environment | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Management, Economic Engineering in Agriculture and Rural Development | Not ranked | 1 | 1% |

| Maternal & Child Nutrition | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| North African Journal of Food and Nutrition Research | Q3 | 1 | 1% |

| Nutrients | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Organic Agriculture | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Second International Conference on Agriculture in an Urbanizing Society | Conference Paper | 1 | 1% |

| Springer, Cham | Book Section | 1 | 1% |

| Sustainable Production and Consumption | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Urban Science | Q1 | 1 | 1% |

| Urban Transformations | Q2 | 1 | 1% |

| Theme | Determinant Codes | Sample Contributing Articles | Frequency (No. of Articles) | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban and Local Food Systems | City, community, local, local food, neighbourhood, proximity, short supply, urban. | [28,29,30,31,32,33,34] | 68 | 99% |

| Farmer Participation and Empowerment | Agency, collaboration, cooperation, decision-making, empowerment, engagement, farmer, inclusion, initiative, involvement, leadership, participation, representation, voice. | [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]; | 64 | 93% |

| Sustainability and Agroecology | Agroecology, biodiversity, conservation, ecological, environment, organic, soil, sustainability. | [28,45,46,47,48] | 52 | 75% |

| Governance, Ethics and Justice | Accountability, ethics, governance, institution, justice, policy, regulation, rights. | [32,39,44,49,50,51,52] | 48 | 70% |

| Resilience and Food Security | Availability, crisis, food security, nutrition, resilience, shock, stability, vulnerability. | [33,34,53,54,55] | 48 | 70% |

| Consumer Preferences and Trust | Awareness, behaviour, confidence, consumer, demand, perception, preference, trust. | [56,57,58,59,60,61] | 45 | 65% |

| Transport, Infrastructure and Logistics | Delivery, distribution, facilities, infrastructure, logistics, storage, supply chain, transport. | [28,35,36,40,45,49,50,62,63] | 33 | 48% |

| Youth, Gender and Inclusion | Empowerment, equity, gender, inclusion, inequality, marginalised, women, youth | [28,50,64,65,66] | 33 | 48% |

| Digital and Market Innovation | Digital, information, innovation, market, platform, technology | [28,34,49,52,59,63,64,67,68,69] | 26 | 38% |

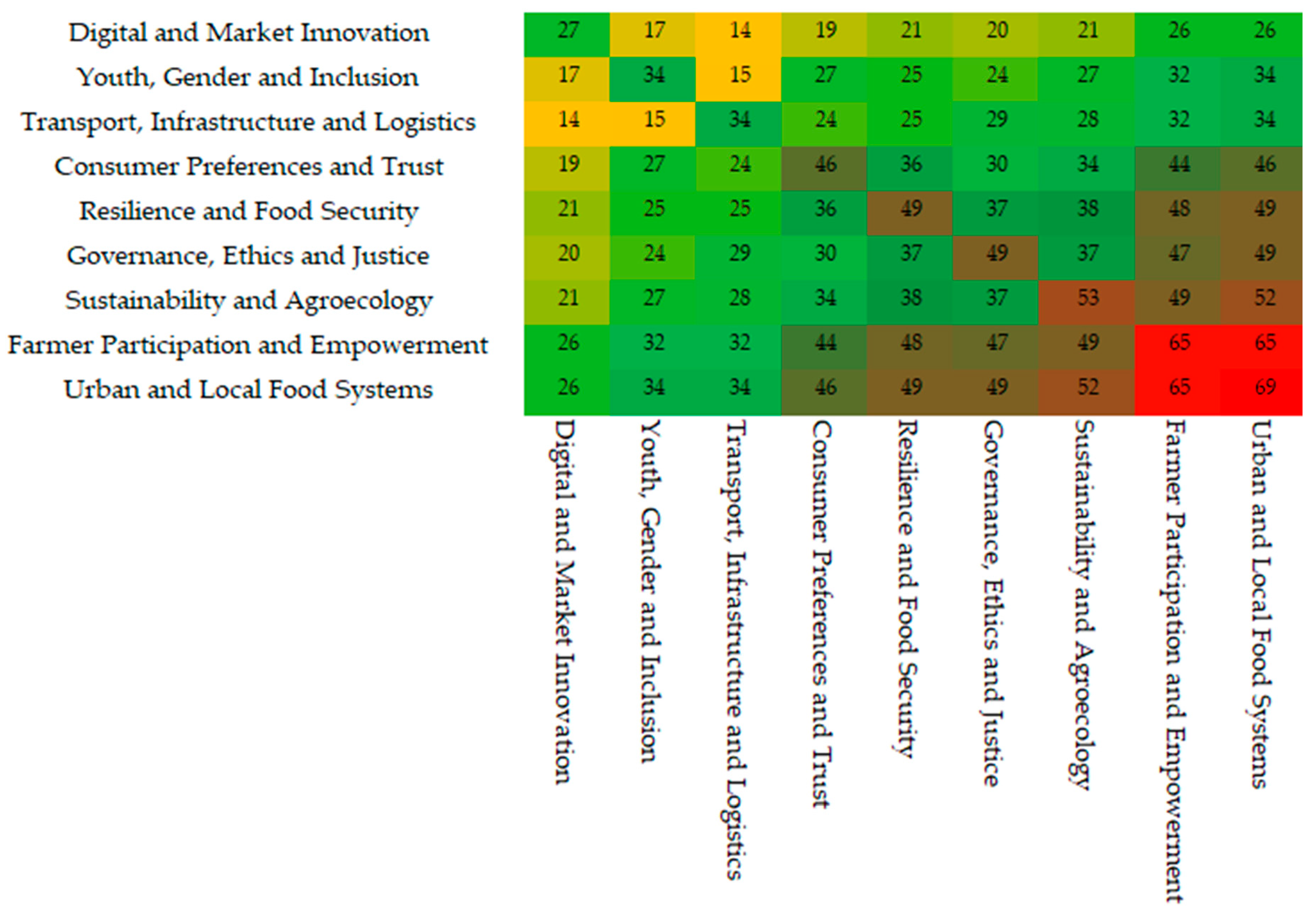

| Cluster Name | Themes | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Governance–Resilience–Sustainability | Governance, Ethics and Justice; Resilience and Food Security; Sustainability and Agroecology. | High co-occurrence (Resilience–Sustainability = 48, Governance–Resilience = 48. They form a core institutional, ethical, and ecological orientation. Conceptually, themes reinforce system-level stability and long-term sustainability. |

| Urbanisation and Participation | Urban and Local Food Systems; Farmer Participation and Empowerment; Consumer Preferences and Trust. | Visual triangular core with strong co-occurrence edges (Urban–Farmer = 65, Urban–Consumer = 46, Farmer–Consumer = 43). Reflection of SFSCs’ social dynamics (consumer behaviour, local production, and empowerment) Central in both structure and conceptual logic. |

| Innovation and Logistics | Digital and Market Innovation; Transport, Infrastructure and Logistics. | Spatially adjacent themes linked to concepts of trust and participation. Conceptual relevance despite moderate co-occurrence edges (Innovation–Transport = 21). Technical enablers of SFSC functionality. |

| Inclusion and Equity | Youth, Gender, and Inclusion. | Moderately connected to multiple themes but positioned at the peripheral, indicating that although acknowledged, themes are weakly integrated. Although grouped in isolation, themes are a critical dimension of equity in the system. |

| Thematic Cluster | African Challenged Targeted | SFSC Interventions |

|---|---|---|

| Governance–Resilience–Sustainability | Climate vulnerability, institutional fragility, food system instability. | Localised agroecological practices, resilience planning, and community governance models. |

| Urbanisation and Participatory Dynamics | Rapid urbanisation, loss of rural power for development, and consumer detachment from local products. | Community-supported agriculture; farmer-led urban markets; trust-based consumer networks. |

| Innovation and Logistics | Inadequate infrastructure, market exclusion, and poor cold chain development. | Smart logistics hubs; mobile-based traceability systems; cooperative digital marketplaces. |

| Inclusion and Equity | Youth unemployment, gendered land access, marginalisation. | Gender-sensitive SFSC programmes; youth co-operatives; inclusive policy design rooted in intersectional equity. |

| Crosscutting | Institutional fragmentation, inequity in participation, and weak digital readiness. | Strengthened governance frameworks; mainstreaming gender and youth equity; digital innovation for coordination, traceability, and market access. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Moyo, E.H.; Pisa, N. Short Food Supply Chain Status and Pathway in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178047

Moyo EH, Pisa N. Short Food Supply Chain Status and Pathway in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):8047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178047

Chicago/Turabian StyleMoyo, Evance Hlekwayo, and Noleen Pisa. 2025. "Short Food Supply Chain Status and Pathway in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 8047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178047

APA StyleMoyo, E. H., & Pisa, N. (2025). Short Food Supply Chain Status and Pathway in Africa: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability, 17(17), 8047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17178047