1. Introduction

Generation Z, defined as individuals born after 1995 [

1,

2], is often perceived as a group of young people who are open-minded, curious about new experiences, and eager to travel [

3]. However, recent studies indicate that, despite these positive traits, an increasing number of Gen Z members limit or forgo travel altogether. The main barriers arise from economic and social factors, as well as growing environmental awareness, which together shape their decisions regarding participation in tourism activities. For the purposes of this article, the commonly used abbreviation Gen Z is employed.

Gen Z is often referred to as the Internet Generation, Google Generation, iGeneration, or Net Gen, highlighting the strong connection this cohort has with the Internet as a primary source for information acquisition and dissemination [

4]. It is also commonly referred to as the e-Generation or Generation C, derived from the English words: communicating, change, computerized, community-oriented, clicking, connected, and creation [

5,

6,

7]. The specific behaviors of Gen Z allow for inferences regarding their characteristic behavior patterns, both in everyday life and in less typical situations [

8].

Currently, Gen Z constitutes approximately 19% of the population in Poland. It is estimated that this group’s share will reach nearly 31% by 2050 and 34% by 2100 [

9]. Reviewing both domestic and international literature, some researchers define Gen Z as individuals born in the 1990s [

10], while others specify the birth years more precisely as 1991–2000 [

10]. There is no universally accepted definition of Generation Z, and both scholars and research institutions propose varying time frames. Some define the cohort as individuals born from 1995 onwards, while others use 1996, 1997, or even 2000 as the starting point, with end years ranging from 2010 to 2012. The Pew Research Center classifies individuals born between 1997 and 2012 as Gen Z [

1]—which aligns exactly with the timeframe adopted for this article. This age range encompasses a group characterized by digital nativity, high social media engagement, and strong environmental awareness, all of which are particularly relevant to contemporary tourist behaviors. Dimock [

1] argues that historical events, social trends, and changes in parenting styles have contributed to the emergence of unique traits characteristic of Gen Z.

Gen Z is a highly digitized, environmentally conscious, socially sensitive, and economically cautious group. Their behaviors—including travel-related behaviors—are strongly influenced by their values, financial capabilities, and the impact of the digital environment. This is the first generation to be fully raised in the digital era, without experience of life without the Internet, smartphones, or social media [

11]. They constantly seek information about various aspects of life, including tourism, through these digital tools [

5,

6]. Their attention span is generally shorter than that of previous generations, which affects learning styles and the effectiveness of advertising formats. Gen Z also exhibits heightened awareness of social issues such as climate change, human rights, gender equality, and minority rights. They are characterized by high levels of empathy and a strong inclination to support pro-social and sustainable initiatives (e.g., conscious consumption, ecotourism). For Gen Z, maintaining a work-life balance is more important than it was for previous generations.

Travel is a particularly important factor influencing the self-development of Gen Z [

12,

13]. This is confirmed by statistical data from the WYSE Travel Confederation and the United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), which show that in 2017, Gen Z accounted for 23% of all tourist arrivals worldwide, with nearly 40% traveling for leisure purposes and 23% for educational purposes (e.g., language stays). Additionally, study-related travel, as well as internships and professional training, accounted for 14% and 13%, respectively [

14,

15]. Gen Z consists of young people who, as it turns out, are enterprising and mindful of their financial situation; in 2016, 62% of individuals took up work during their studies to develop professionally and gain new experiences [

16]. Representatives of Gen Z are not so much “giving up on traveling” as they are redefining its meaning and form. For Gen Z, modern technologies constitute an integral part of contemporary culture and lifestyle [

16]. A highly important topic that should be increasingly discussed in various forums, conferences, and academic publications is the clear connection between tourism and a conscious approach to sustainable tourism.

In the context of challenges related to sustainable development and social changes, understanding the motivations and barriers of Gen Z regarding travel is essential for shaping tourism policies that address both the needs of young people and the necessity of protecting the natural environment. Therefore, the aim of this study is to verify hypotheses concerning the main reasons for travel reduction among Gen Z and to identify the relationships between selected demographic factors, such as place of residence and source of income, and the tourism activity of this social group.

Analysis of data from a 2024 study shows that, although the vast majority of respondents (84.5%) report participation in tourism, a significant portion (15.5%) limit or refrain from travel for various reasons. The most frequently cited barriers were lack of free time and financial constraints—unstable employment, high living costs, and education significantly affect young people’s financial capabilities. Environmental awareness also plays a notable role, with nearly one-third of respondents indicating it as a reason for limiting travel. Gen Z is increasingly declaring a reduction in or avoidance of travel due to concerns for the natural environment and a desire to lower their carbon footprint, which aligns with global consumer trends. Economic factors, understood as high prices of tourism services, appear to have somewhat less impact. Moreover, the results indicate a relative independence of tourism activity from place of residence and source of income, suggesting a possible homogenization of travel behaviors among Gen Z.

This article aims to contribute to the ongoing debate on sustainable travel behaviors of Gen Z. The research findings may assist policymakers, educators, and tourism professionals in developing more inclusive and environmentally friendly tourism strategies that align with the values of young travelers. To gain a better understanding of the topic and achieve the research objectives, a comparison was made between the travel behaviors of Gen Z and those of other generations.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Definition and Determinants of Tourist Behavior

Tourist behaviors refer to a set of actions undertaken by individuals or groups in relation to their participation in tourism travel. These behaviors include the decision-making process prior to the trip, activities carried out during the stay, and the evaluation of the experience after the trip’s completion. They are part of the broader category of consumer behaviors but pertain specifically to the context of tourism—voluntary travel conducted outside the place of permanent residence and unrelated to professional duties.

Tourist behaviors encompass all activities related to the movement of people outside their permanent place of residence for the purpose of rest, exploration, recreation, or other tourism-related goals [

17]. On the other hand, V. Middleton defines tourist behaviors as “the ways in which tourists choose, purchase, consume, and evaluate tourism products” [

18].

Tourist behavior is influenced by a range of factors—both individual and external. The most significant of these include motivations, needs, availability of time and financial resources, personality, lifestyle, socio-economic status, cultural trends, as well as the impact of media and public opinion [

19]. New technologies also play an important role, having transformed the way trips are planned and conducted—including booking, information searching, and experience sharing [

16].

Contemporary research on tourist behavior is interdisciplinary in nature and incorporates elements of psychology, sociology, geography, marketing, and economics. The analysis of such behavior enables a better understanding of the preferences of different tourist groups (e.g., Gen Z), which is crucial for designing travel offers, managing destinations, and conducting effective promotional activities [

20].

As noted by T. Żabińska (1994), consumer behavior in the tourism market involves identifying the need for travel within the broader context of household consumption needs, accepting this need, and making the decision to travel. In the literature, these are referred to as tourist behaviors [

16,

21].

2.2. Characteristics of Generation Z’s Tourist Behavior—Challenges and Trends

The discussion on changes in consumer behavior in the tourism market requires particular attention to young people, especially members of Gen Z. Consumers representing Generations Y and Z already play, and will increasingly continue to play in the coming years, a decisive role in shaping the dynamics of tourism economy development, as well as in transforming both the demand and supply sides of the tourism market [

22,

23,

24,

25].

The tourist behavior of Gen Z has been studied by, among others, Gai, Ekasari, Ratnawista, Hatmawan, and Nurcholifah [

16]. Their research indicates that this generation is heavily dependent on smartphones, which undeniably facilitate searching for travel information, making bookings, and posting travel reviews online, including on highly popular social media platforms. Similar conclusions were drawn by McCorkindale, DiStaso, and Sisco [

26].

Interesting findings regarding the tourist behaviors of Gen Z—in comparison with those of Generations X and Y—are presented by Uysal [

27]. The author notes that Gen Z differs significantly from Gen X and Gen Y. A detailed review of both domestic and international literature reveals a lack of substantial, conclusion-driven publications addressing this specific issue.

One of the few studies presenting empirical data on tourist behavior among British university students is the publication by Bicikova [

28]. Additionally, recent research by Liu, Jiang, and Muhammad (2024) highlights the significant influence of TikTok short videos on the travel intentions of Gen Z and Millennials, emphasizing how social media content can shape travel decisions through immersive flow experiences [

29].

The literature highlights the clear dependence of Generation Y on new information technologies. It is believed that the tools associated with these technologies have become an integral part of the culture and lifestyle of Gen Z [

16,

30].

A review of the literature reveals that the topic of tourism consumption among Gen Z remains relatively under-researched [

16,

27,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Studies specifically addressing this consumer segment are scarce. In this context, the aim of the present paper,

“Tourist Behavior of Gen Z: Why Young Adults Refrain from Traveling”, is to fill this knowledge gap. The research focuses on representatives of Gen Z aged 19–24. By the end of 2023, Gen Z in Poland numbered 3695.8 thousand people (9.8% of the total population), of which the targeted age segment accounted for 2135.9 thousand individuals, or 5.7% of the population [

34].

Tourist behavior refers to the decision-making processes of individuals and groups related to the choice of travel destinations, forms, and modes of travel. In the literature, it is grounded in classical consumer behavior theories, such as the Engel–Kollat–Blackwell model, which considers both internal and external stimuli as key determinants of decision-making [

35,

36].

Motivational models also play an important role in tourism, particularly the push-pull model [

37], which explains travel behavior as the result of push factors (e.g., boredom, the need for relaxation) and pull factors (e.g., destination attractions).

Increasingly, analyses of tourist behavior incorporate a post-materialist perspective [

38], which suggests that younger generations are guided by non-material values such as social responsibility, environmental protection, and the pursuit of authentic experiences.

When making travel-related decisions, Gen Z pays close attention to economic factors. Job insecurity, rising living costs, inflation, and expensive tourism services contribute to a decrease in travel activity among young adults [

38,

39]. The Deloitte report (2023) reveals that over 60% of Gen Z respondents cite financial limitations as their main barrier to travel [

40]. Environmental considerations also play a crucial role—Gen Z is strongly motivated to minimize negative environmental impacts. They avoid excessive flying, support local communities, and opt for sustainable forms of travel, such as ecotourism or train travel [

41].

Importantly, the decision to reduce or forgo travel among Gen Z is not solely driven by financial constraints but often reflects a conscious ethical choice. The main reasons include the following:

The desire to reduce their carbon footprint;

Awareness of the negative effects of mass tourism on the environment and local communities;

Limited financial resources;

The increasing importance of values such as sustainability, minimalism, and localism.

The social meaning of travel is also evolving—among Gen Z, it is no longer primarily associated with prestige, but rather with personal development and the responsible exploration of other cultures. The concept of slow travel, emphasizing unhurried and reflective journeys, is gaining prominence [

42,

43]. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on Gen Z’s mobility. It transformed mobility patterns by promoting trends such as “staycations”, local tourism, and remote work while traveling. The crisis also brought about health concerns and a heightened aversion to mass tourism [

44,

45].

The pandemic caused a 74% decline in global tourism activity [

46,

47], and scholars have noted that COVID-19 accelerated discourse around the need for sustainable tourism development. Many researchers now advocate for transformative reforms aimed at aligning tourism with environmental and societal well-being [

48,

49]. In the post-pandemic era, tourism is increasingly seen as a critical component of economic recovery [

50,

51].

Moreover, high inflation has further influenced Gen Z’s travel behaviors. Rising costs of transportation, accommodation, and ancillary services have created additional barriers to travel. Combined with broader economic uncertainty, these factors often lead Gen Z to postpone travel plans or opt for low-budget alternatives [

52,

53].

Gen Z (born after 1995) differs significantly from previous generations in its approach to tourism. Research highlights several key characteristics: a high level of environmental and social awareness; a preference for authentic, affordable, and value-driven travel experiences; and the digitalization of the travel process, with planning, booking, and sharing experiences primarily taking place online [

39]. According to a report by Booking.com (2023), over 70% of Gen Z respondents stated that the environmental impact of travel influences their decisions, and more than half reported having reduced air travel in recent years [

50].

Sustainable development in tourism is based on a balance between economic, social, and environmental needs. For Gen Z, these values are particularly significant—numerous studies indicate that young consumers are much more likely than older generations to express concern about climate change, ethical consumption, and the responsible use of natural resources [

8]. Young people are increasingly environmentally conscious. Gen Z understands the impact of transportation—especially air travel—on CO

2 emissions. According to a study conducted by Booking.com (2023), as many as 53% of young travelers reported deliberately limiting air travel or choosing alternative modes of transportation (e.g., trains and bicycles) to reduce their carbon footprint [

50].

It should also be emphasized that Gen Z’s travel decisions are shaped not only by their values related to sustainability but also by economic limitations. Many young people face an unstable job market, high living costs, and limited savings [

44]. Although environmentally friendly travel is desirable, it is not always affordable—train travel can be more expensive than budget airlines, and eco-hotels often cost more than chain accommodations.

Contemporary tourism is inherently linked to the challenges of sustainable development. Gen Z, having grown up under the strong influence of climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and increasing environmental awareness, has attracted particular interest from researchers and tourism industry practitioners. Although they are considered open-minded and mobile, growing evidence indicates a decline in their tourism activity [

17,

54,

55].

Environmental awareness is a significant factor shaping the travel behaviors of Gen Z, as confirmed by recent studies. Ribeiro et al. indicate that pro-environmental values and a sense of environmental responsibility significantly influence attitudes and the willingness to engage in pro-environmental behaviors [

56]. Additionally, research conducted on a sample of Gen Z individuals demonstrated a significant impact of environmental concern on the choice of low-emission transportation and eco-friendly accommodation options [

57].

Psychosocial factors also play a significant role—Gen Z faces stress, uncertainty, climate anxiety, and post-pandemic caution [

35,

44]. For some, choosing not to travel is not solely a conscious, value-based decision, but also a coping mechanism in response to these pressures.

Gen Z is not so much giving up on travel as it is redefining its meaning. Guided by the values of sustainable development, young people are increasingly choosing less invasive forms of travel—or foregoing travel altogether—if they perceive it to be unethical or harmful to the planet. The future of tourism will depend on whether the industry can respond to the needs of this generation by combining accessibility, authenticity, and ecological responsibility.

A relatively new phenomenon in the literature is “climate travel guilt”. According to study by The Statista Research Department and the organization Possible, one in three members of Gen Z in the UK felt ashamed after taking a flight, even if it was an occasional trip [

48]. In research conducted by GUS in Poland, 37% of respondents aged 18–26 declared that they had decided not to travel “out of guilt toward the planet”, regardless of cost or time [

46]. This can be linked to the concept of “moral tourism consumption”, in which young people make travel decisions not only for practical reasons but also for ideological ones.

In Europe, the phenomenon of “flight shame” has become increasingly widespread and is having a tangible effect on Gen Z’s travel decisions [

43]. Although Gen Z has the potential to be a leader in sustainable tourism, its decisions often reflect a tension between the desire to explore the world and the need to remain true to personal values. In practice, this results in a change in travel style—and sometimes even in limiting travel altogether.

Young people are increasingly opting for local, low-budget, and eco-friendly forms of tourism, such as domestic travel, “slow travel”, volunteer tourism, agritourism, and eco-hostels. It is also worth noting Gen Z’s critical attitude toward mass tourism. They are more likely to recognize the negative consequences of overtourism: environmental degradation, displacement of local communities, and rising housing and service prices [

20]. As a result, many choose to avoid “overtouristed” destinations (e.g., Venice, Barcelona), instead preferring less popular locations.

In the context of psychological factors, eco-shame—also known as climate shame—is an increasingly recognized phenomenon influencing travel decisions. Although research specifically addressing climate shame in Gen Z remains limited, a growing body of work on eco-anxiety and eco-guilt suggests that feelings of environmental guilt may reduce the willingness to use high-carbon-emission transportation [

57].

Place of residence—particularly the distinction between rural and urban areas—is an important factor differentiating access to transport infrastructure, cultural and recreational offerings, and tourism services, which can influence both the frequency and patterns of travel [

8,

58,

59,

60,

61]. Additionally, city dwellers are more likely to engage in short-term weekend tourism, whereas individuals living in rural areas may face greater transport and financial limitations [

62,

63].

Income source also affects travel decisions, as it determines both the availability of financial resources and the way individuals manage their budgets. Studies show that individuals who support themselves financially (e.g., students working part-time) are more likely to limit their travel spending due to financial constraints, compared with those supported by their families, who tend to report greater financial freedom [

64,

65,

66]. Seasonal or part-time workers may have more free time but often lack sufficient financial resources to travel [

66,

67]. Such factors can influence travel decisions in various ways, even if they do not show statistically significant correlations in quantitative analyses.

The analysis of socio-demographic factors confirms that place of residence significantly impacts the travel frequency of Gen Z [

68]. Studies demonstrate that living conditions in urban and rural areas shape differences in travel motivations and opportunities. Similar conclusions are drawn from analyses of the socio-demographic mobility of young adults [

69,

70]. Regarding sources of income as a determinant of tourism activity, the literature highlights the strong impact of financial barriers on engagement in pro-environmental and tourism behaviors. Although direct studies on the income sources of Gen Z are lacking, research on attitudes toward ecological costs indicates that budget constraints often hinder the implementation of pro-environmental tourism choices, despite a declared willingness to make such decisions [

71,

72].

In summary, the following research hypotheses have been formulated:

H1. Although lack of free time and financial barriers are the main factors limiting travel among Gen Z, environmental awareness is also an important factor within this group.

H2. Climate shame, as a new psychological factor related to the perception of sustainability, has a clear impact on the travel decisions of Gen Z.

H3. Place of residence influences travel frequency.

H4. Source of income determines tourism activity.

Based on a detailed review of both domestic and international literature, it is evident that a significant gap exists in the form of a limited number of in-depth studies addressing the motives behind Generation Z’s decisions to refrain from traveling. Existing publications tend to focus primarily on the preferences, travel styles, and technologies used by young tourists, while there is a noticeable lack of analyses exploring the underlying mechanisms and conditions leading to the reduction or complete abandonment of travel. The few studies that do address this issue are often descriptive in nature and lack a comprehensive analytical approach.

3. Materials and Methods

The research was based on a questionnaire containing 19 questions of both fixed-choice and open-ended types, as well as a demographic section. The questionnaire was developed based on available literature [

73,

74,

75]. Prior to the main study, technical and comprehension-related pilot tests were conducted on a smaller sample to enhance the reliability and validity of the questionnaire. The survey was carried out in 2024, focusing on the travel behaviors and decisions of respondents during that year. The questionnaire was administered online, and the survey link was disseminated via student groups on social media platforms from 1 October to 1 December 2024. Participation was voluntary and anonymous.

The study sample consisted of 412 respondents representing Gen Z in Poland. Only individuals aged 19 to 27 who were currently studying or had completed their studies were included, as this group constitutes a significant segment of young adults characterized by unique behavioral patterns and approaches to tourism. Members of Gen Z with higher education, or currently pursuing it, tend to exhibit greater social and environmental awareness. The research sample was representative.

The survey included questions covering areas such as barriers limiting travel opportunities, attitudes toward ecology, and sustainable tourism. The demographic section collected information on respondents’ gender, age, source of income, and place of residence (

Table 1).

The majority of respondents were women. Most lived in cities with populations exceeding 100,000 inhabitants, and their primary source of income was employment. Participants either held higher education degrees or were currently pursuing their studies.

The collected data were analyzed statistically using Microsoft Excel. To examine the relationship between qualitative variables—specifically, respondents’ sources of income and their reported travel for tourism purposes in 2024—a chi-square test of independence was applied. This test allows for the assessment of whether a statistically significant association exists between two categorical variables [

75,

76].

Initially, data on sources of income were grouped into eleven categories; however, due to small sample sizes in some groups (fewer than five observations), which can distort chi-square test results, categories with low counts were aggregated into a single “other” group. This approach follows recommendations in the methodological literature, which state that the chi-square test requires sufficiently large expected frequencies in each cell of the contingency table [

76,

77].

The analysis was conducted on 412 observations, with a significance level set at α = 0.05. The chi-square test results include the test statistic value, degrees of freedom, and p-value, enabling verification of the null hypothesis of independence between the variables studied.

Furthermore, thematic analysis was applied to the open-ended responses of the study participants. This method enabled the identification and interpretation of recurring themes that respondents indicated as reasons for limiting travel. The analysis was exploratory in nature and involved sequential coding of the responses, followed by grouping the codes into main thematic categories. This approach facilitated a deeper understanding of the barriers influencing the travel behaviors of Gen Z. The analysis process was conducted following the classical model of thematic analysis, encompassing stages such as data familiarization, coding, theme identification and verification, and interpretation of the results [

78,

79].

4. Results

This chapter presents the results of a study on the participation of Gen Z representatives in tourism travel in 2024, as well as the reasons for limiting or refraining from tourism. This study incorporates both a quantitative perspective (statistical data analysis) and a qualitative approach (interpretation of open-ended responses), allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the complex motivations and barriers faced by young adults when planning their tourism activities.

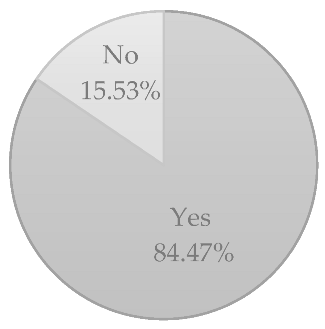

Figure 1 presents the responses to the question: “Did you travel for tourism purposes in 2024?” The pie chart clearly shows a dominant majority of “Yes” responses, accounting for 84.5% of all answers. Meanwhile, 15.5% of respondents reported that they did not travel for tourism purposes in 2024.

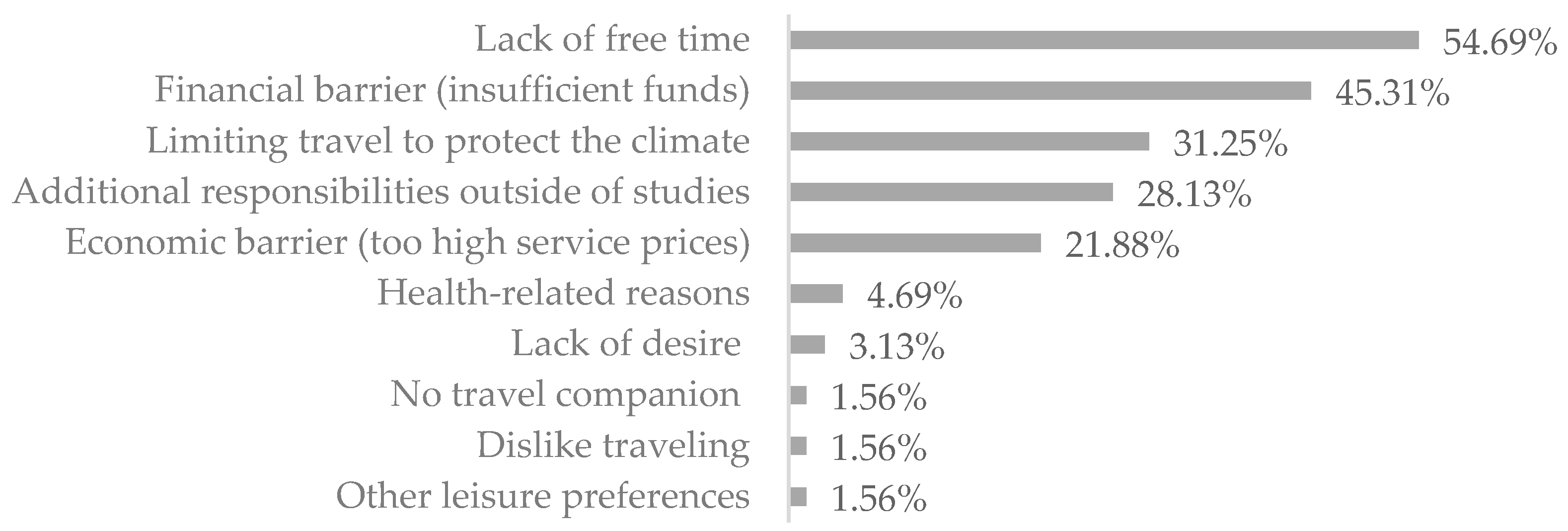

Figure 2 illustrates respondents’ answers to the question: “Why did you not travel for tourism purposes in 2024?” with the option to select multiple responses. The most frequently indicated reasons were lack of free time (54.7%) and financial barriers due to insufficient funds (45.3%). A significant proportion of respondents also reported travel limitations resulting from ecological concerns (31.3%), highlighting the growing awareness of tourism’s environmental impact. Other notable reasons included additional responsibilities outside of study or work (28.1%) and economic barriers related to high service costs (21.9%). Less frequent responses included lack of desire, absence of a travel companion, and health-related reasons.

Table 2 presents the distribution of responses to the question regarding participation in tourism travel in 2024, broken down by respondents’ place of residence. Understanding how spatial context and the degree of urbanization influence tourist behavior is crucial for the effective planning of sustainable socio-economic development and for promoting tourism accessible to all social groups.

The analysis of data from a sample of 412 individuals indicates that the highest proportion of people traveling for tourism purposes comes from cities with populations exceeding 100,000 (38.11%). This group likely has greater financial resources, better infrastructure, and wider access to information and tourism services. Additionally, the high travel participation rate in this category reflects better mobility among residents in large urban centers, aligning with global urbanization trends and increased consumption of recreational services.

Smaller cities, with populations ranging from 21,000 to 100,000, show lower but still significant percentages of travelers (approximately 21.42%). In these environments, factors such as transportation availability, income levels, and local resources may limit travel frequency, indicating the need to support initiatives that enhance tourism accessibility beyond major cities.

The lowest participation in tourism is reported by rural residents (17.96%), which may result from various barriers, including economic, infrastructural, and social factors. People living in rural areas often have limited access to public transportation, and their incomes may be lower than those in larger urban centers, translating into reduced opportunities for tourism. Moreover, the nature of rural life may be associated with different leisure preferences or higher levels of family and work commitments that restrict travel.

To examine whether there is a statistically significant relationship between respondents’ place of residence and their tourism activity in 2024, a chi-square test of independence was applied. The data were analyzed across five residence categories: rural areas, cities with fewer than 20,000 inhabitants, 21,000–50,000, 51,000–100,000, and cities with over 100,000 residents. Travel responses were classified binarily (yes/no). The chi-square test results (χ2 = 3.14, df = 4, p > 0.05) indicated no grounds to reject the null hypothesis of no association between the variables. In other words, place of residence is not statistically linked to the declaration of tourism travel in 2024 within the studied sample.

Despite observed percentage differences in the share of travelers across categories (e.g., higher rates in large cities), statistical analysis suggests that these differences could be due to random fluctuations and do not reflect significant population-level differences. This result indicates that, within the studied group, participation in tourism does not significantly differ based on place of residence, which may imply a reduction in traditional spatial barriers and a greater homogenization of tourism behaviors.

Table 3 illustrates the variation in responses to the question regarding tourism travel in 2024 depending on respondents’ sources of income. In the context of sustainable development and social inclusion, understanding the links between economic stability and tourism activity is crucial for designing policies that support tourism accessibility for different social groups.

In the analyzed sample, the dominant source of income was employment, accounting for over half of the respondents (52.91%). A significant majority of this group (45.39% of all respondents) reported participation in tourism travel, indicating a positive correlation between regular income and the ability to utilize tourism services. It is important to emphasize that the financial stability provided by employment not only increases access to tourism but also contributes to regional economic development through increased demand for tourism services.

Another important group comprises individuals supported by family (33.01%), of whom over one quarter (26.94%) traveled for tourism purposes. This result highlights the role of social capital and family support as factors facilitating recreational activity, although to a lesser extent than income from employment. It may also indicate greater sensitivity of this group to economic barriers.

Scholarships and various combinations of income sources (e.g., scholarships, employment, investments) constitute a smaller percentage, and their impact on tourism behaviors is moderate. The lower participation of individuals relying on investments, family pensions, or student loans in tourism travel may indicate limitations arising from the instability or insufficiency of these funding sources.

An analysis of the relationship between respondents’ sources of income and their declarations regarding tourism travel in 2024 was conducted using the chi-square test of independence. Income sources were classified into four groups: employment, family, scholarship, and the category “other”, which included smaller income groups to ensure adequate counts for statistical analysis. The chi-square test result (χ2 = 0.58, df = 3, p = 0.90) indicates no statistically significant relationship between the source of income and undertaking tourism travel in the studied sample. This means that, regardless of the form of financing their expenses (whether through employment, family support, scholarships, or other sources), respondents reported similar tourism behaviors.

These results suggest that among the surveyed individuals, the source of income is not a dominant determinant of tourism activity. The high homogenization of behaviors may indicate sustainable and uniform tourism patterns within the analyzed population.

Analyzing the open-ended responses of the participants, several key reasons for limiting travel among Gen Z representatives can be identified:

“I don’t travel because I am aware of how much transport, especially air travel, affects the climate. I try to reduce my carbon footprint and choose other ways to spend my free time”.

- 2.

Financial barrier:

“After paying rent and bills, there is little left. Travel is a luxury I simply cannot afford”.

- 3.

Lack of free time:

“Between studies, work, and family duties, I don’t have time to plan a trip. Sometimes even a weekend at home is a luxury”.

- 4.

No need to travel:

“I don’t feel the need to go anywhere. I prefer spending time locally with family and friends. That relaxes me more than sightseeing”.

- 5.

Health reasons:

“Due to chronic health issues, traveling is too physically and organizationally demanding for me”.

- 6.

Lack of a travel companion:

“I have no one to travel with, and I don’t feel comfortable going alone. Most friends don’t have time or money”.

Moreover, among respondents who refrain from traveling for ecological reasons, the following statements appeared:

“I try to limit my impact on the environment, so I give up long-distance trips”.

“Flying several times a year is excessive for me. If I do travel somewhere, I choose the train. Last year, I didn’t travel at all because I didn’t want to contribute to emissions”.

“Climate issues are important to me, so I don’t fly and limit my travels. I prefer spending time locally or traveling within Poland”.

“I don’t feel the need to travel far. I feel a bit guilty when I see so many people flying for fun, and at the same time, it annoys me that all climate summits are held in person. Are these supposed to help the planet? Most participants get there by plane”.

“I gave up my summer vacation because it would have meant a flight and high environmental costs for both the planet and me. I prefer other ways to relax—for example, bike trips close to home”.

Among respondents who reported refraining from tourism travel for ecological reasons, a high level of environmental sensitivity and a willingness to limit personal consumption behaviors for the sake of the planet were observed. The cited statements indicate that decisions not to travel were motivated by a desire to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, particularly those related to air transport, as well as by a striving for consistency between declared values and lifestyle.

Respondents emphasized the need to decrease their personal environmental impact, choosing alternative modes of transportation—such as trains—or completely foregoing travel. An important element was also a critical assessment of global climate actions, including the discrepancies between institutional declarations and their actual practices.

Notably, young people often opt for local forms of recreation, such as bike trips or short domestic trips, which they perceive as more sustainable. Their narratives also include the notion of so-called eco-guilt, which influences the limitation of their tourism aspirations.

This analysis shows that among young adults, a new way of thinking about tourism is emerging—not through the prism of exploration or consumption, but through environmental responsibility. Such an approach may represent a cultural shift conducive to achieving sustainable development goals, particularly SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) [

79,

80]. Increasing climate awareness and environmental care encourage more responsible consumer decisions. Gen Z limits travel not due to a lack of desire to explore the world, but from a sense of responsibility for the environment and the planet’s future. This reflects an ethical approach to consumption and a new understanding of a “good life”—living in harmony with nature rather than at the expense of its resources.

5. Discussion

This article presents the results of the study entitled

Tourist Behaviors of Gen Z: Why Are Young People Limiting Their Travel?, a topic that has rarely been addressed by Polish researchers [

13,

56,

81,

82]. This issue has been examined far more frequently by scholars from other countries [

28,

33,

83,

84,

85]. Only a limited number of studies have focused on the travel behaviors of university students, a specific subgroup of Gen Z often referred to as older post-millennials [

28].

The travel behaviors of Gen Z differ significantly from those of older generations, both in Poland and globally. Key areas of divergence include travel frequency, motivations, barriers, and attitudes toward sustainable tourism. According to the “Travel Trends 2023” report by Statista, only 49% of respondents in Europe aged 19–27 (i.e., Gen Z) reported traveling at least once a year, compared with 67% in the 35–49 age group (Generations Y and X) and 73% in the 50 + age group. The younger generation also reported engaging more in domestic than international travel, mainly due to financial constraints and environmental concerns [

48]. In Poland, data from the 2022 “Youth Tourism” report by Statistics Poland (GUS) show that only 38% of people aged 16–24 traveled for tourism purposes at least once during the year. In contrast, this figure was 54% for those aged 25–39, and 61% for the 40–59 age group [

46].

Gen Z differs significantly from older generations in terms of travel motivations. According to Booking.com’s Gen Z Travel Report (2022), as many as 56% of young travelers in this group cite the search for authentic cultural experiences as a key factor in their travel decisions, compared with 38% among millennials [

53]. Additionally, 49% of Gen Z travelers value the opportunity to explore lesser-known destinations and avoid mass tourism (versus 31% of Generation X). Notably, 35% indicate that sustainability and ecological concerns influence their choice of travel destinations [

53].

Despite their reported high climate awareness, the European Travel Commission (2023) [

86] report reveals a certain dissonance between Gen Z’s values and their actual behavior. While many young people express a desire to travel responsibly, this does not always translate into concrete tourism choices, such as avoiding air travel or selecting low-emission modes of transportation [

40].

The paradox of environmental concern lies in the fact that, although ecological awareness is increasing, it does not always translate into concrete pro-environmental actions. From a psychological perspective, a key role is played by the sense of agency—a lack of belief in one’s ability to impact the environment limits the undertaking of such actions. Meanwhile, from an economic perspective, price barriers and the absence of appropriate economic incentives hinder environmentally friendly consumer choices [

87]. Additionally, social norms can influence behaviors that sometimes contradict individual ecological values. An interdisciplinary approach combining psychology, economics, and sociology allows for a better understanding and overcoming of this paradox.

One of the most frequently cited reasons—aside from lack of time—is limited financial capacity. Gen Z members are often at the beginning of their professional careers, working on temporary contracts or in part-time jobs. The high cost of living, inflation, job insecurity, and rising prices of tourism services make travel increasingly a luxury. Research conducted by StudentUniverse (The State of Student & Youth Travel, 2023) confirms that 76% of Gen Z representatives identify cost as the main barrier to travel planning [

88]. In Deloitte’s 2023 Global Gen Z and Millennial Survey [

40], 42% of Gen Z respondents indicated a lack of sufficient financial resources as the main barrier to travel, while 38% reported limiting travel due to climate concerns. In comparison, only 21% of millennials and 13% of Generation X reported similar environmentally driven travel restrictions [

40].

Research conducted in Poland by the Polish Economic Institute (PIE) in 2023 showed that 47% of individuals aged 19–27 reported having given up at least one flight due to environmental concerns [

89]. In contrast, among respondents aged 40 and older, fewer than 22% reported similar behavior [

87].

According to the EY Future Consumer Index—Sustainability and Travel (2023), 64% of Gen Z individuals in Europe actively seek forms of tourism aligned with sustainability principles [

90]. This proportion is significantly higher compared with Generation X (41%) and Baby Boomers (34%) [

90]. An important issue is the growing ecological awareness. Gen Z is characterized by a strong sense of environmental responsibility, which is reflected in the phenomenon known as

flight shame—the guilt associated with air travel. Many young people avoid long-distance trips, especially by plane, in order to reduce their carbon footprint. According to a 2025 YouGov report (

Gen Z and Sustainability: Travel Habits of a Conscious Generation), nearly half of Gen Z respondents report limiting travel for environmental reasons [

91]. A total of 62% of young Europeans (aged 19–27) declare that sustainability matters to them when planning a trip; however, only 27% actually check environmental certifications when booking accommodation or transport [

86].

The findings presented in this study contribute to the existing body of knowledge on consumer tourism behavior, with particular emphasis on the older post-Millennial segment within Gen Z. In this context, the article aims to address a research gap in the current literature. At the same time, certain limitations of the study must be acknowledged, including the nationality of the respondents (Poland) and the relatively small sample size. Further research is planned on a broader scale, not only to include a larger number of participants but also to compare the findings with data from respondents in other EU countries and potentially from Asia. An international research project involving several foreign universities would be a valuable step forward and could significantly enhance our understanding of this issue.

The main reasons for limiting or refraining from tourism-related travel include lack of time, financial barriers (i.e., insufficient funds), and environmental concerns. Although Gen Z is considered open-minded, curious about the world, and eager to gain new experiences, an increasing number of studies indicate a clear trend of reduced tourism activity in this age group. Several key factors contribute to this phenomenon, stemming from both economic conditions and psychosocial circumstances.

The decline in travel among Gen Z is not only the result of a lack of free time or financial barriers but also of a new psychosocial phenomenon—the internalization of sustainability values in the form of “climate shame” and ecological identity. In conclusion, members of Gen Z are not abandoning travel entirely; rather, they approach it more cautiously and selectively than previous generations, guided not only by practical constraints but also by their personal values.

The concept of “climate shame” proves particularly relevant in the context of the present study. Many respondents reported feelings of guilt or moral discomfort after engaging in activities perceived as harmful to the environment—especially after air travel. Some participants explicitly stated that this feeling of guilt prompted them to reduce the frequency of their travels or to forgo specific trips. These reported emotions indicate that climate shame not only exists but may directly influence travel decision-making. The results align with previous studies conducted in the UK by Possible and The Statista Research Department [

48], as well as research by Polish Economic Institute [

89], confirming the validity of Hypothesis H2. This new psychological mechanism may reflect a broader shift in the moral value system of consumer behavior in tourism.

The situation differs with regard to Hypothesis H3, which assumed a relationship between place of residence and the tendency to refrain from traveling. The conducted chi-square test did not show statistical significance for this relationship (p > 0.05). Similarly, Hypothesis H4, which addressed the impact of income source on travel decisions, was not supported—the test outcome (p = 0.90) indicated no significant relationship. Therefore, both H3 and H4 were rejected.

An analysis of respondents’ answers indicates that 31.3% of individuals who did not travel for tourism purposes in 2024 cited climate protection as a significant barrier influencing their decision to limit or refrain from travel. This relatively high percentage reflects a growing environmental awareness within the surveyed group, particularly among Gen Z, which increasingly makes consumption decisions with environmental considerations in mind.

6. Conclusions

The conclusions drawn from the presented study, as well as the literature review, confirm the need for further in-depth research on this issue. In recent years, research has been conducted on the tourism behavior of the young generation—such as by the UNWTO (

Youth and Sustainable Tourism: Global Survey Report), among others [

92], as well as by academic institutions analyzing the influence of environmental and economic values on travel decisions (e.g., [

93,

94]). Nevertheless, the current state of knowledge remains insufficient. There is a need for systematic and comprehensive research that captures the dynamically evolving attitudes and expectations of Gen Z toward tourism. Only with up-to-date data will it be possible to effectively plan and create tourism offers, as well as to pursue sustainable development policies within the sector.

The qualitative responses further reveal that Gen Z is not only aware of the environmental impact of tourism—particularly air travel—but also voluntarily modifies its behavior in accordance with personal ecological convictions. Some respondents reported avoiding long-distance trips, choosing trains over airplanes, or preferring local travel, perceiving such decisions as expressions of environmental concern. These attitudes reflect the internalization of sustainability norms and may indicate the emergence of a post-consumerist approach to tourism.

In conclusion, Gen Z is not abandoning travel altogether but engages in it with greater awareness and deliberation. This trend creates opportunities for the development of more sustainable and responsible tourism in the future. The phenomenon is critically important for research on sustainable development and responsible tourism, as it signals a shift in consumer motivations toward minimizing negative environmental impacts. The ecological barrier not only limits tourism mobility but also highlights the potential for growth in alternative, more climate-friendly forms of tourism.

Incorporating this aspect into the analysis of tourist behavior is essential for shaping policies and strategies that promote sustainable tourism. It is also crucial for businesses and organizations operating in the tourism sector, which can adapt their offerings to align with the values and expectations of young consumers. In the context of global climate challenges, understanding and addressing the ecological barrier becomes indispensable for developing environmentally friendly practices and ensuring the long-term viability of tourism.

From a sustainable development perspective, it is important to consider these disparities when planning tourism policies to ensure inclusivity and equal access to tourism services regardless of place of residence. Supporting the mobility of residents from rural areas and smaller towns through the development of infrastructure and financial support programs may help reduce inequalities and promote more sustainable and equitable tourism.

The findings suggest that efforts to promote tourism can be effective across various regions, regardless of the level of urbanization. Nevertheless, other socio-economic or demographic factors may play a stronger role in shaping tourism behavior, highlighting the need for further, in-depth research.

The findings on the limitations of tourism activity among Gen Z have significant implications for stakeholders in the tourism sector and institutions responsible for youth policy. Firstly, they underscore the need to tailor tourism offerings to the actual financial capacities of young people—through budget-friendly tourism options, promotional offers, student discounts, and flexible payment schemes. Secondly, tourism enterprises should invest in products aligned with sustainable development principles, such as promoting rail transport, ecotourism, local products, and short-distance travel with a low carbon footprint.

For policymakers, the results suggest the importance of supporting youth mobility programs (e.g., Erasmus+, subsidized educational trips, national scholarship initiatives) that can reduce tourism exclusion. Moreover, initiatives supporting the mental well-being of young people—including workshops on stress management, adaptation to change, or solo travel—may contribute to increasing their travel activity.

From a marketing perspective, tourism companies should develop authentic, transparent, and engaging messages that resonate with Gen Z values, such as environmentalism, diversity, and inclusivity. Collaboration with micro-influencers and the use of channels such as TikTok and Instagram Reels are recommended practices.

From the perspective of public policy and the tourism industry, the study highlights the need for the following:

The development and promotion of low-emission and local forms of tourism;

Greater inclusion of young, climate-conscious consumers in tourism offerings;

A redefinition of marketing strategies in the context of environmental ethics.

This article contributes to the broader discussion on sustainable mobility and responsible consumption, showing that for a growing number of Gen Z individuals, traveling is not solely a form of leisure but also a moral and ecological decision. In the face of escalating climate challenges, these motivations are expected to play an increasingly important role in shaping tourism behaviors. Understanding such attitudes is essential for aligning tourism practices with the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, particularly Goal 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and Goal 13 (Climate Action).

One of the main limitations of this study is the narrow focus on students belonging to Gen Z. The study exhibits sample bias, primarily reflected in the disproportionate representation of participants from large cities and those with higher education. Data were collected using a survey method, which relies on self-reported responses that may not always reflect actual behavior. The research was conducted in Poland, and the results may be influenced by local social, economic, and cultural conditions, limiting the possibility of direct comparison with findings from other countries. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevents observation of changes in attitudes and behaviors over time, for instance, in response to economic or social developments.

For future research, cross-regional or cross-cultural comparisons would be valuable to identify differences in travel-related constraints experienced by Gen Z depending on the socio-economic context. Comparative studies could distinguish universal from local phenomena across cultures and regions—for example, between Western countries (e.g., USA, Germany) and Asian countries (e.g., Japan, China), or between Northern (e.g., Scandinavia) and Southern countries (e.g., Latin America), highlighting differences in social values, trust, and individualism. Another promising direction is examining the impact of social media and platform algorithms on Gen Z’s travel decisions, as well as the long-term effects of ongoing crises (climate, economic, health-related) on travel patterns. Expanding the study to include qualitative methods—such as in-depth interviews or focus groups—could provide deeper insights into the motivations, fears, and needs of Gen Z.

_Li.png)