Job Satisfaction in the Face of Organizational Stress: Validating a Stress Symptoms Survey and Exploring Stress-Related Predictors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Job Stress

2.2. Lack of Support

2.3. Stress Symptoms

2.4. Job Satisfaction and Stress

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Procedure and Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.2.1. Stress Symptoms Survey

3.2.2. Job Stress Survey—JSS

3.2.3. Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire—MSQ

4. Results

4.1. Stress Symptoms Survey Properties

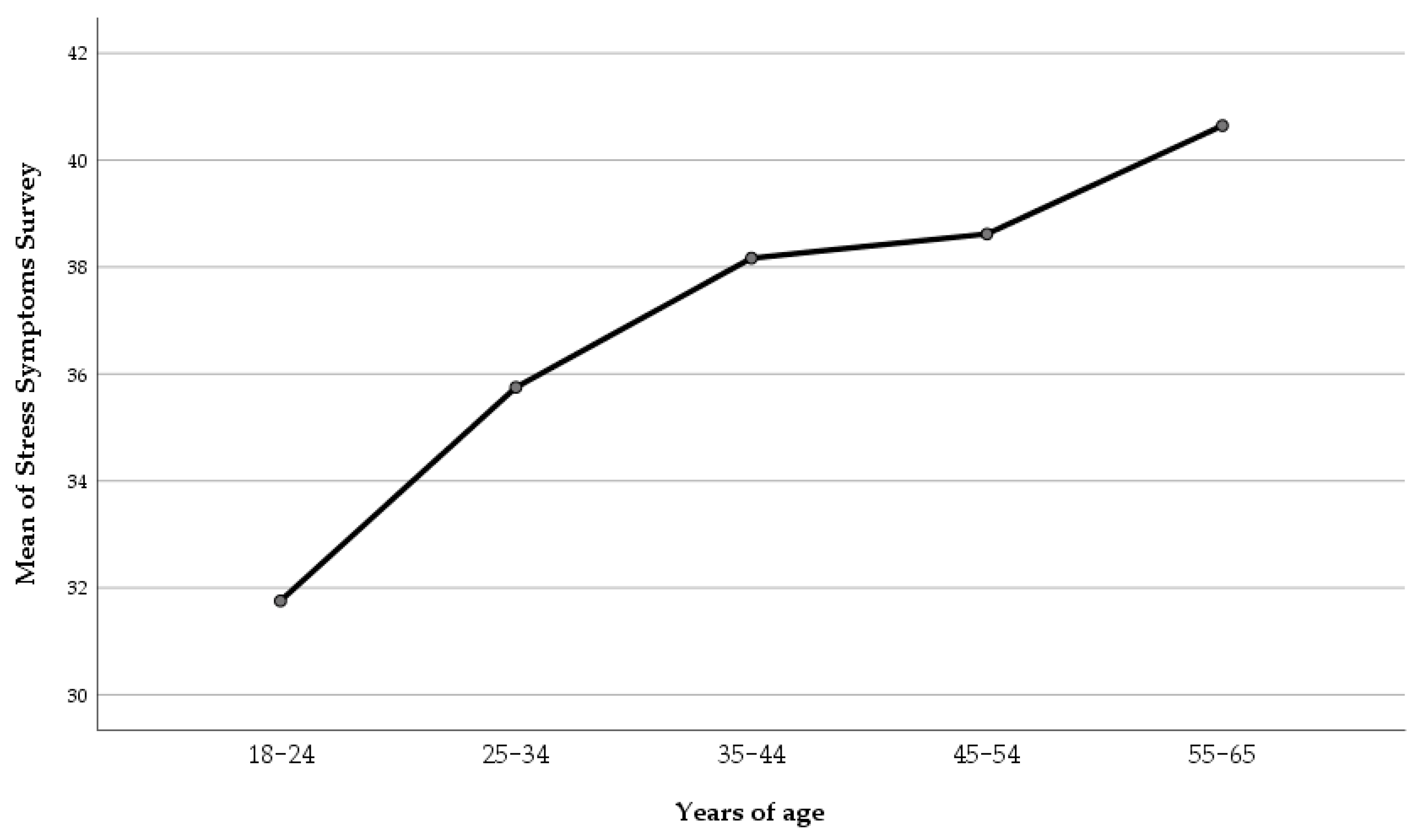

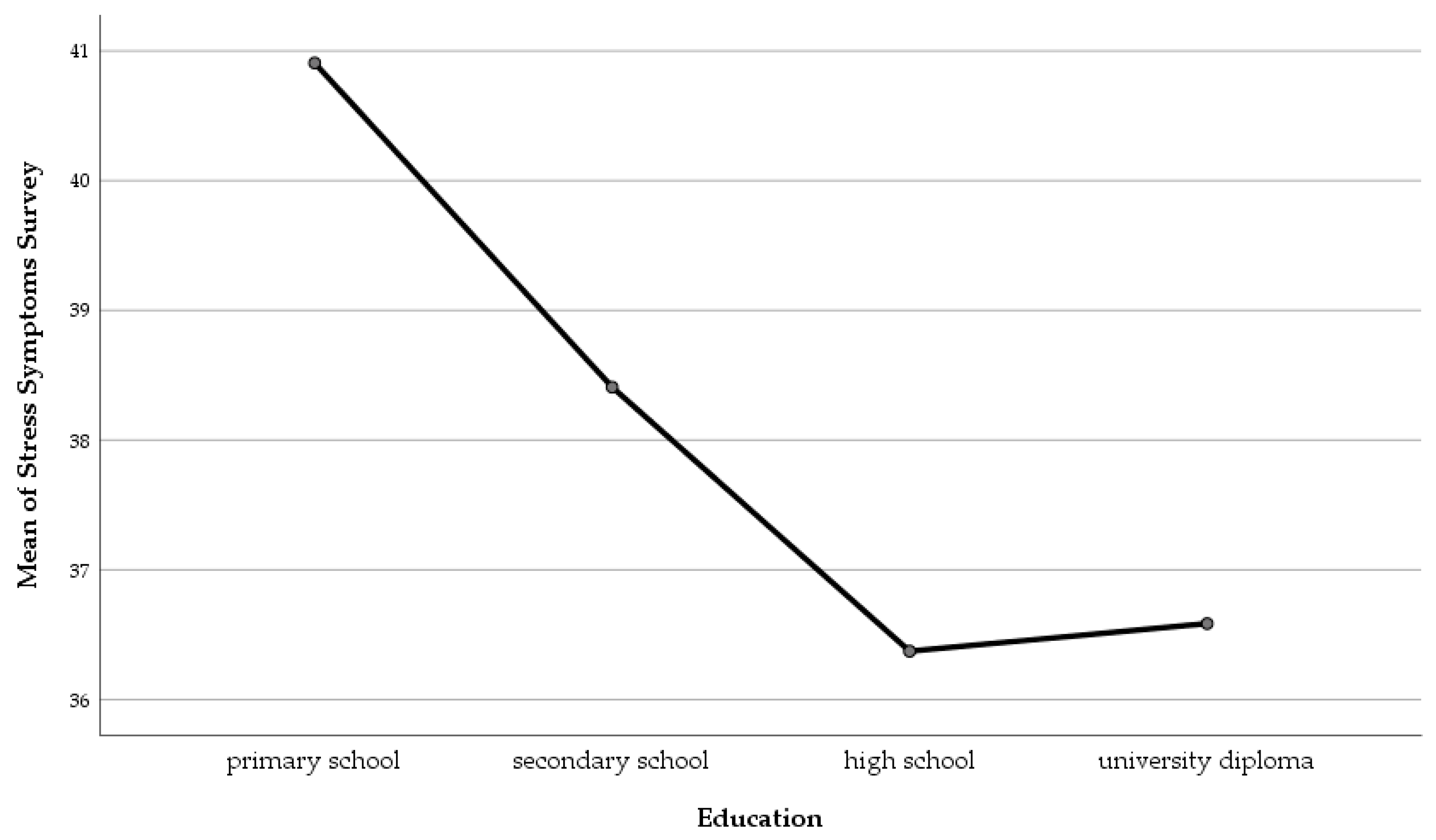

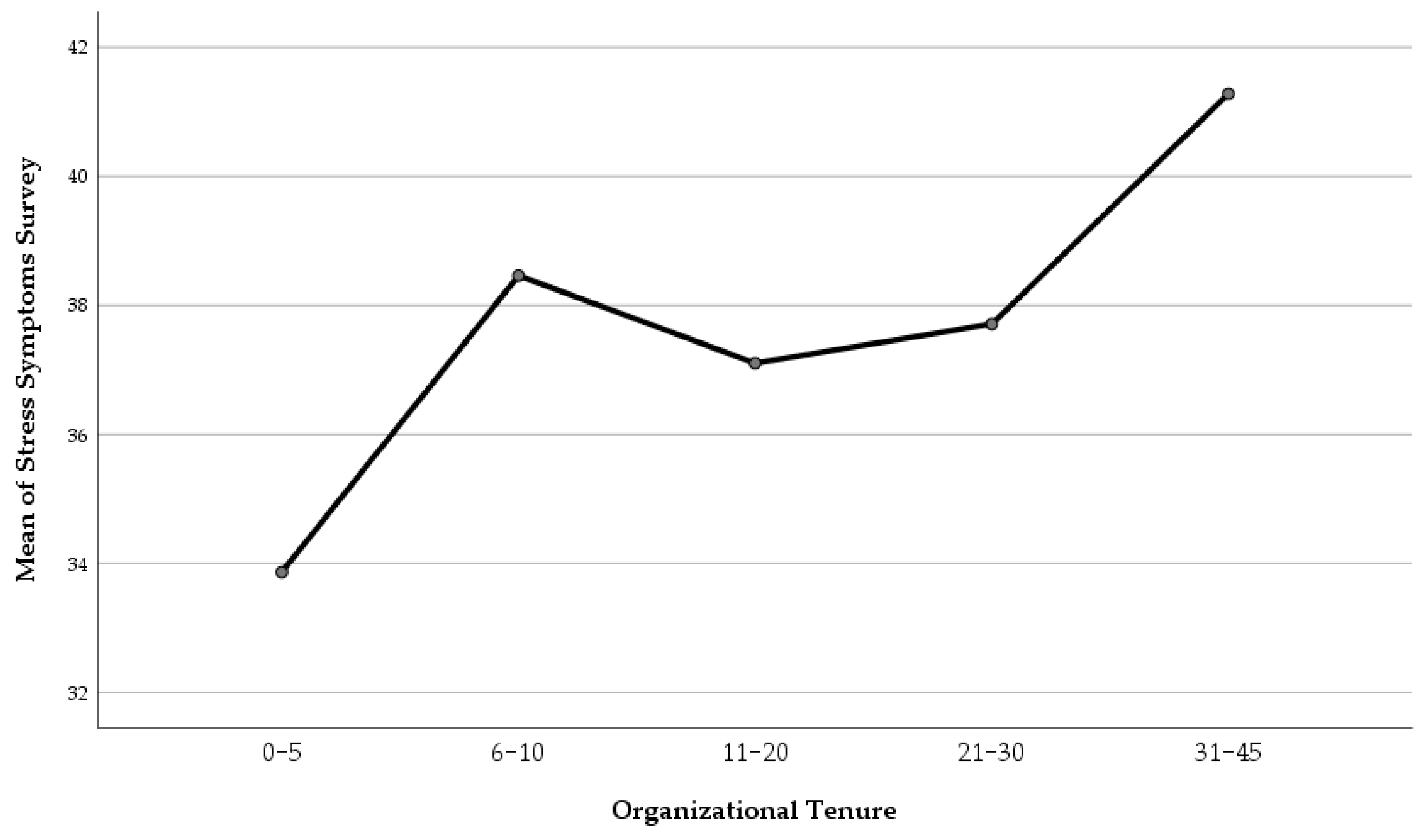

4.2. Stress Symptoms Survey Results

4.3. Correlation and Multiple Regression

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSQ | Occupational Stress Questionnaire |

| SSS | Stress Symptoms Survey |

| JSS | Job Stress Survey |

| MSQ | Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire |

| EFA | Exploratory factor analysis |

References

- Litchfield, P.; Cooper, C.; Hancock, C.; Watt, P. Work and Well-being in the 21st Century. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, E.; K.A., Z. Job Satisfaction and Job-Related Stress. In Psychological Empowerment and Job Satisfaction in the Banking Sector; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 87–126. ISBN 978-3-319-94258-2. [Google Scholar]

- Rasool, S.F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Samma, M. Sustainable Work Performance: The Roles of Workplace Violence and Occupational Stress. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, J.; Peeters, M.C.W. The Vital Worker: Towards Sustainable Performance at Work. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFrank, R.S.; Ivancevich, J.M. Stress on the Job: An Executive Update. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 1998, 12, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attar, M.; Çağlıyan, V.; Abdul-kareem, A. Evaluating the Moderating Role of Work-Life Balance on the Effect of Job Stress on Job Satisfaction. Istanb. Bus. Res. 2021, 49, 201–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruldoss, A.; Kowalski, K.B.; Parayitam, S. The Relationship between Quality of Work Life and Work-Life-Balance Mediating Role of Job Stress, Job Satisfaction and Job Commitment: Evidence from India. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2021, 18, 36–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.D.; Mullins-Jaime, C.; Balogun, A.O. A Path Analysis Study of Relationships between Long Work Hours, Stress, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention among Mine Workers. Int. J. Workplace Health Manag. 2025, 18, 86–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Zafar, S. Effect of Work Pressure on Job Satisfaction Levels Among Physiotherapists in Uttar Pradesh. J. Neonatal Surg. 2025, 14, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, A.; Singh, A.P. Unraveling the Burnout-Work-Life Balance Nexus: A Secondary Data Analysis. Int. J. Indian Psychol. 2024, 12, 1447–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaredić, B.; Hinić, D.; Stanojević, D.; Zečević, S.; Ignjatović-Ristić, D. Temperament, Socijalna Podrška i Faktori Stresa Na Poslu u Predviđanju Zadovoljstva Životom i Poslom Kod Lekara i Psihologa. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2017, 74, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berber, N.; Slavić, A.; Gašić, D. Employees’ Work-Life Balance in the Contemporary Business Environment in Serbia; Centre for Evaluation in Education and Science (CEON/CEES): Belgrade, Serbia, 2024; pp. 24–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mamula, M. Sta to Radi Zaposlene? Osiguranik: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Finnøy, O.J. Job Satisfaction and Stress Symptoms among Personnel in Child Psychiatry in Norway. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2000, 54, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rožman, M.; Grinkevich, A.; Tominc, P. Occupational Stress, Symptoms of Burnout in the Workplace and Work Satisfaction of the Age-Diverse Employees. Organizacija 2019, 52, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, J.L.; Walker, L.J.S. Self-Reported Stress Symptoms in Farmers. J. Clin. Psychol. 1988, 44, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, A.-L.; Leppänen, A.; Lindström, K.; Ropponen, T. OSQ: Occupational Stress Questionnaire: User’s Instructions; Institute of Occupational Health, Publication Office: Helsinki, Finland, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Elkin, A. Stress Management for Dummies, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-118-61259-0. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, J.; Hwang, S.; Seo, W.; Kang, Y. Relationship between Rework of Engineering Drawing Tasks and Stress Level Measured from Physiological Signals. Autom. Constr. 2021, 124, 103560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harzer, C.; Ruch, W. The Relationships of Character Strengths with Coping, Work-Related Stress, and Job Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VandenBos, G.R. (Ed.) APA Dictionary of Psychology, 2nd ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-4338-1944-5. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S.; Lazarus, R.S. If It Changes It Must Be a Process. Study of Emotion and Coping During Three Stages of a College Examination. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 48, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/home (accessed on 12 April 2025).[Green Version]

- Mensah, A. Job Stress and Mental Well-Being among Working Men and Women in Europe: The Mediating Role of Social Support. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameron, L.; Pierce, S.; Conroy, J. Occupational Stress Measures of Tenure-Track Librarians. J. Librariansh. Inf. Sci. 2021, 53, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, H.; Turen, U.; Gokmen, Y.; Tuz, O. Perceived Organizational Support, Stress Coping Behaviors and Mediating Role of Psychological Capital: Special Education and Rehabilitation Centers. Sci. Ann. Econ. Bus. 2017, 64, 375–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, I.M.; Jepsen, D.M. The Impact of Specific Job Stressors on Psychological Contract Breach and Violation. Hum. Factors Ergon. Manuf. 2015, 25, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vagg, P.R.; Spielberger, C.D. Occupational Stress: Measuring Job Pressure and Organizational Support in the Workplace. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluemper, D.H.; Mossholder, K.W.; Ispas, D.; Bing, M.N.; Iliescu, D.; Ilie, A. When Core Self-Evaluations Influence Employees’ Deviant Reactions to Abusive Supervision: The Moderating Role of Cognitive Ability. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 159, 435–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, J.; Chong, S.H.; Chen, J.; Johnson, R.E.; Ren, X. The Interplay of Low Identification, Psychological Detachment, and Cynicism for Predicting Counterproductive Work Behaviour. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 69, 59–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friganović, A.; Selič, P.; Ilić, B.; Sedić, B. Stress and Burnout Syndrome and Their Associations with Coping and Job Satisfaction in Critical Care Nurses: A Literature Review. Psychiatr. Danub. 2019, 31, S21–S31. [Google Scholar]

- Chaharaghran, F.; Tabatabaei, S.; Rostamzadeh, S. The Impact of Noise Exposure and Work Posture on Job Stress in a Food Company. Work 2022, 73, 1227–1234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadipour, F.; Pourranjbar, M.; Naderi, S.; Rafie, F. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Iranian Office Workers: Prevalence and Risk Factors. J. Med. Life 2018, 11, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamisa, N.; Oldenburg, B.; Peltzer, K.; Ilic, D. Work Related Stress, Burnout, Job Satisfaction and General Health of Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eddy, P.; Wertheim, E.H.; Kingsley, M.; Wright, B.J. Associations between the Effort-Reward Imbalance Model of Workplace Stress and Indices of Cardiovascular Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 83, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, G. Stress: Concepts, Cognition, Emotion, and Behavior: Handbook of Stress Series, Volume 1; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Verkuil, B.; Atasayi, S.; Molendijk, M.L. Workplace Bullying and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis on Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0135225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.A.; Stephens, K.K. Shifting From Wellness at Work to Wellness in Work: Interrogating the Link Between Stress and Organization While Theorizing a Move Toward Wellness-in-Practice. Manag. Commun. Q. 2019, 33, 616–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, A.S.; Rajendran, D.; Theiler, S. Job Stress, Well-being, Work-Life Balance and Work-Life Conflict among Australian Academics. E-J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 8, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C.L.; Rout, U.; Faragher, B. Mental Health, Job Satisfaction, and Job Stress among General Practitioners. In Managerial, Occupational and Organizational Stress Research; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maharaj, S.; Lees, T.; Lal, S. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in a Cohort of Australian Nurses. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makaremi, N.; Morgan, G.T.; Yildirim, S.; Jakubiec, J.A.; Robinson, J.; Touchie, M.F. A Framework for Evaluating the Impact of Buildings on Inhabitant Well-Being. Build. Environ. 2025, 280, 113117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, J.C.; Henderson, D.F. Occupational Stress: Preventing Suffering, Enhancing Well-being. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidger, J.; Brockman, R.; Tilling, K.; Campbell, R.; Ford, T.; Araya, R.; King, M.; Gunnell, D. Teachers’ Well-being and Depressive Symptoms, and Associated Risk Factors: A Large Cross Sectional Study in English Secondary Schools. J. Affect. Disord. 2016, 192, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siedlecki, K.L.; Salthouse, T.A.; Oishi, S.; Jeswani, S. The Relationship Between Social Support and Subjective Well-Being Across Age. Soc. Indic. Res. 2014, 117, 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Seligman, M.E.P. Very Happy People. Psychol. Sci. 2002, 13, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michie, S.; Williams, S. Reducing Work Related Psychological Ill Health and Sickness Absence: A Systematic Literature Review. Occup. Environ. Med. 2003, 60, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, J.; Degen, L.; Minder, K.; Rieger, M.A.; Weltermann, B.M. Strong Association of Perceived Chronic Stress with Leadership Quality, Work–Privacy Conflict and Quantitative Work Demands: Results of the IMPROVE Job Study. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Shachat, J.; Wei, S. Cognitive Stress and Learning Economic Order Quantity Inventory Management: An Experimental Investigation. Decis. Anal. 2022, 19, 229–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindek, S. Failing Is Derailing: The Underperformance as a Stressor Model. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberger, R.; Cummings, J.; Armeli, S.; Lynch, P. Perceived Organizational Support, Discretionary Treatment, and Job Satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 1997, 82, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinson, H. Reciprocation: The Relationship between Man and Organization. In Industrial Organizations and Health: Selected Readings; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A. The Influence of Perceived Organizational Support, Perceived Coworker Support & Debriefing on Work-Related Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress in Florida Public Safety Personnel. Ph.D. Thesis, College of Health and Public Affairs, Orlando, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, A.; Unruh, L.; Liu, X.; Wharton, T.; Zhang, N. Individual and Organizations Factors Associated with Professional Quality of Life in Florida EMS Personnel. Int. J. Emerg. Serv. 2018, 7, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, H.A.; Yang, J.; Vandenberg, R.J.; DeJoy, D.M.; Wilson, M.G. Perceived Organizational Support’s Role in Stressor-Strain Relationships. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 789–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawang, S. Moderation or Mediation? An Examination of the Role Perceived Managerial Support Has on Job Satisfaction and Psychological Strain. Curr. Psychol. 2010, 29, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W.B. The Job Demands-Resources Model of Burnout. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhoades, L.; Eisenberger, R. Perceived Organizational Support: A Review of the Literature. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-L.; Hung, C.-H.; Ching, G.S. Shifting between Counterproductive Work Behavior and Organizational Citizenship Behavior: The Effects of Workplace Support and Engagement. Int. J. Res. Stud. Educ. 2016, 6, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryee, S.; Chay, Y.W. Workplace Justice, Citizenship Behavior, and Turnover Intentions in a Union Context: Examining the Mediating Role of Perceived Union Support and Union Instrumentality. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Kong, D.T.; Kim, K.Y. Social Support at Work: An Integrative Review. J. Organ. Behav. 2021, 42, 229–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Lee, Y.H. Understanding Sport Coaches’ Turnover Intention and Well-Being: An Environmental Psychology Approach. Psychol. Health 2022, 37, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cabrera, A.M.; Suárez-Ortega, S.M.; Gutiérrez-Pérez, F.J.; Miranda-Martel, M.J. The Influence of Supervisor Supportive Behaviors on Subordinate Job Satisfaction: The Moderating Effect of Gender Similarity. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1233212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshizer, B.; Knapp, D.E. Revisiting the Buffering Hypothesis: Social Support, Work Stressors, Stress Related Symptoms, and Negative Affectivity in a Sample of Public School Teachers. OALib 2016, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, J.; Steptoe, A.; Cropley, M. An Investigation of Coping Strategies Associated with Job Stress in Teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1999, 69, 517–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorsteinsson, E.B.; Brown, R.F.; Richards, C. The Relationship between Work-Stress, Psychological Stress and Staff Health and Work Outcomes in Office Workers. Psychology 2014, 5, 1301–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongsuwan, N.; Phanniphong, K.; Na-Nan, K. How Job Stress Influences Organisational Commitment: Do Positive Thinking and Job Satisfaction Matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Wills, T.A. Stress, Social Support, and the Buffering Hypothesis. Psychol. Bull. 1985, 98, 310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; Kurita, H.; Haratani, T.; Fujii, K.; Ishibashi, T. Direct and Buffering Effects of Social Support on Depressive Symptoms of the Elderly with Home Help. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1999, 53, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfin, D.; Wallace, J.; Baez, S.; Karr, J.E.; Terry, D.P.; Hibbler, T.; Yengo-Kahn, A.; Newman, S. Social Support, Stress, and Mental Health: Examining the Stress-Buffering Hypothesis in Adolescent Football Athletes. J. Athl. Train. 2024, 59, 499–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, A.; Bharti, V.; Tiwari, M. Effects of Work Stress on Psychological Well-Being and Job Satisfaction: A Review. In Revisioning and Reconstructing Paradigms and Advances in Industry 5.0; Kolkata Press Books: Kolkata, India, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing Company: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gross, J.J. Antecedent-and Response-Focused Emotion Regulation: Divergent Consequences for Experience, Expression, and Physiology. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1998, 74, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S. Physiology and Neurobiology of Stress and Adaptation: Central Role of the Brain. Physiol. Rev. 2007, 87, 873–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Scherer, N.; Felix, L.; Kuper, H. Prevalence of Depression, Anxiety and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in Health Care Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Mahmood, N.; Javaid, S.F.; Khan, M.A. The Effect of Lifestyle Interventions on Anxiety, Depression and Stress: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrisham, R.; Paknejad, M.; Soliemanifar, O.; Sadegh-Nejadi, S.; Meshkani, R.; Ashtary-Larky, D. The Influence of Psychological Stress on the Initiation and Progression of Diabetes and Cancer. Int. J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 17, e67400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, A.; Kivimäki, M. Stress and Cardiovascular Disease: An Update on Current Knowledge. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2013, 34, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glendon, A.I. OSQ: Occupational Stress Questionnaire: User’s Instructions. Saf. Sci. 1995, 21, 171–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierk, B.; Kohlmann, S.; Kroenke, K.; Spangenberg, L.; Zenger, M.; Brähler, E.; Löwe, B. The Somatic Symptom Scale–8 (SSS-8): A Brief Measure of Somatic Symptom Burden. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Severity of Acute Stress Symptoms—Adult. Available online: https://tsaco.bmj.com/content/tsaco/6/1/e000623/DC2/embed/inline-supplementary-material-2.pdf?download=true (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Stress Symptom Checklist. Available online: https://thepsychologycenter.biz/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/STRESSSYMPTOMSCHECKLIST1.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Muldoon, J. The Hawthorne Studies: An Analysis of Critical Perspectives, 1936–1958. J. Manag. Hist. 2017, 23, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafui Agbozo, G. The Effect of Work Environment on Job Satisfaction: Evidence from the Banking Sector in Ghana. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 5, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppock, R. Job Satisfaction of Psychologists. J. Appl. Psychol. 1937, 21, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spector, P. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997; ISBN 978-0-7619-8922-6. [Google Scholar]

- Hoxha, G.; Simeli, I.; Theocharis, D.; Vasileiou, A.; Tsekouropoulos, G. Sustainable Healthcare Quality and Job Satisfaction through Organizational Culture: Approaches and Outcomes. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziner, A.; Rabenu, E.; Radomski, R.; Belkin, A. Work Stress and Turnover Intentions among Hospital Physicians: The Mediating Role of Burnout and Work Satisfaction. Rev. Psicol. Trab. Las Organ. 2015, 31, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raziq, A.; Maulabakhsh, R. Impact of Working Environment on Job Satisfaction. Procedia Econ. Finance 2015, 23, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, Q. Teacher Well-Being in Chinese Universities: Examining the Relationship between Challenge—Hindrance Stressors, Job Satisfaction, and Teaching Engagement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flinchbaugh, C.; Luth, M.T.; Li, P. A Challenge or a Hindrance? Understanding the Effects of Stressors and Thriving on Life Satisfaction. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2015, 22, 323–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samartha, M.V.; Begum, M.; Lokesha, M. Impact of Job Stress On Job Satisfaction-An Empirical Study. Indian J. Commer. Manag. Stud. 2011, 2, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, J.I.; Winskowski, A.M.; Engdahl, B.E. Types of Workplace Social Support in the Prediction of Job Satisfaction. Career Dev. Q. 2007, 56, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.; Yeh, H.; Nguyen, K.-V.H. How Job Involvement Moderates the Relationship Between Organizational Commitment and Job Satisfaction: Evidence in Vietnam. Adv. Soc. Sci. Res. J. 2018, 5, 136–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahjat Abdallah, A.; Yousef Obeidat, B.; Osama Aqqad, N.; Khalil Al Janini, M.N.; Dahiyat, S.E. An Integrated Model of Job Involvement, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: A Structural Analysis in Jordan’s Banking Sector. Commun. Netw. 2017, 9, 28–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raykov, M. Employer Support for Innovative Work and Employees’ Job Satisfaction and Job-Related Stress. J. Occup. Health 2014, 56, 244–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, T.L.; Lauzier, M. Workplace Bullying and Job Satisfaction: The Buffering Effect of Social Support. Univers. J. Psychol. 2014, 2, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, E.; Bjaalid, G.; Mikkelsen, A. Work Climate and the Mediating Role of Workplace Bullying Related to Job Performance, Job Satisfaction, and Work Ability: A Study among Hospital Nurses. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 2709–2719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, J.; Paliadelis, P.S.; Valenzuela, F.R. Factors That Affect the Job Satisfaction of Saudi Arabian Nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrgović, P.; Walton, A.L.J.; Sandall, D.L.; Dinić, B. Measuring Employees’ Communication for Innovation: The Employee Innovation Potential Scale. J. Pers. Psychol. 2023, 22, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comrey, A.l.; Lee, H.B. A First Course in Factor Analysis, 2nd ed.; Psychology Press: East Sussex, UK, 1992; ISBN 978-0-8058-1062-2. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, A.E.; Mazzola, J.J.; Bauer, J.; Krueger, J.R.; Spector, P.E. Can Work Make You Sick? A Meta-Analysis of the Relationships between Job Stressors and Physical Symptoms. Work Stress 2011, 25, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.M.; Seidler, A.; Nübling, M.; Latza, U.; Brähler, E.; Klein, E.M.; Wiltink, J.; Michal, M.; Nickels, S.; Wild, P.S. Associations of Fatigue to Work-Related Stress, Mental and Physical Health in an Employed Community Sample. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigemi, J.; Mino, Y.; Tsuda, T.; Babazono, A.; Aoyama, H. The Relationship between Job Stress and Mental Health at Work. Ind. Health 1997, 35, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, J.I.E.; You, J.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, C.; Wang, H. Job Stress, Burnout, Depression Symptoms, and Physical Health among Chinese University Teachers. Psychol. Rep. 2009, 105, 1248–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.S.; Sulsky, L.M.; Uggerslev, K.L. Effects of Job Stress on Mental and Physical Health. In Handbook of Mental Health in the Workplace; Thomas, J.C., Hersen, M., Eds.; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002; pp. 61–82. ISBN 0-7619-2255-5. [Google Scholar]

- Salvagioni, D.A.J.; Melanda, F.N.; Mesas, A.E.; González, A.D.; Gabani, F.L.; de Andrade, S.M. Physical, Psychological and Occupational Consequences of Job Burnout: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, A.-L.; Leppänen, A.; Jahkola, A. Validity of a Single-Item Measure of Stress Symptoms. Scand. J. Work. Environ. Health 2003, 29, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, W.; Bratzke, L.C.; Oakley, L.D.; Kuo, F.; Wang, H.; Brown, R.L. The Association between Psychological Stress and Metabolic Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 2019, 20, 1651–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrgović, P. Job Stressors and Interpersonal Conflict Resolution Strategies of Social Workers in Serbia: Comparison with Other Public Institutions. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Dawis, R.; England, G.; Lofquist, L. Manual for the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire. Man. Minn. Satisf. Surv. 1967, 22, 120. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, H.; Proença, M.T. Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire: Psychometric Properties and Validation in a Population of Portuguese Hospital Workers. Investig. E Interv. Em Recur. Hum. 2014, 471, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen Parboteeah, K.; Addae, H.M.; Cullen, J.B. National Culture and Absenteeism: An Empirical Test. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2005, 13, 343–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermsittiparsert, K.; Petchchedchoo, P.; Kumsuprom, S.; Panmanee, P. The Impact of the Workload on the Job Satisfaction: Does the Job Stress Matter? Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Olafsen, A.H.; Halvari, H. Motivational Mechanisms in the Relation between Job Characteristics and Employee Functioning. Span. J. Psychol. 2017, 20, E38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Mean | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Item-Total r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Headaches | 2.4 | 0.933 | 0.223 | −0.663 | 0.376 |

| 2. Pains and “stabbing” sensations | 2.15 | 0.963 | 0.509 | −0.38 | 0.599 |

| 3. High blood pressure | 1.69 | 1.021 | 1.496 | 1.495 | 0.415 |

| 4. Poor sleep | 2.29 | 1.03 | 0.46 | −0.385 | 0.473 |

| 5. Skin rashes | 1.38 | 0.713 | 2.182 | 5.286 | 0.307 |

| 6. Poor digestion | 2.01 | 0.993 | 0.79 | 0.069 | 0.437 |

| 7. Stomach ulcer | 1.21 | 0.663 | 3.78 | 15.118 | 0.373 |

| 8. Asthma attacks | 1.15 | 0.533 | 4.397 | 21.622 | 0.361 |

| 9. Nervousness | 2.58 | 1.078 | 0.279 | −0.541 | 0.569 |

| 10. Lack of motivation, feeling depressed | 2.05 | 1.023 | 0.786 | −0.05 | 0.665 |

| 11. Heart conditions | 1.31 | 0.775 | 2.937 | 8.827 | 0.427 |

| 12. Changes in appetite | 1.83 | 0.954 | 1.018 | 0.522 | 0.549 |

| 13. Feeling exhausted | 2.7 | 1.114 | 0.057 | −0.824 | 0.609 |

| 14. Smoking tobacco | 2.42 | 1.61 | 0.542 | −1.363 | 0.177 |

| 15. Consumption of alcoholic beverages | 2.07 | 1.027 | 0.675 | −0.178 | 0.247 |

| 16. Difficulty concentrating and maintaining attention | 2.02 | 0.943 | 0.695 | −0.03 | 0.524 |

| 17. Frequent mood swings | 2.1 | 0.963 | 0.613 | −0.186 | 0.633 |

| 18. Lack of self-confidence | 1.87 | 0.938 | 0.968 | 0.486 | 0.562 |

| 19. Excessive sweating | 1.77 | 0.93 | 1.028 | 0.288 | 0.467 |

| 20. Weakened immune system and frequent colds | 1.98 | 0.926 | 0.876 | 0.611 | 0.466 |

| 21. Taking sick leave | 1.48 | 0.673 | 1.373 | 1.825 | 0.326 |

| 22. Irritability and arguing with others | 1.83 | 0.901 | 1.024 | 0.862 | 0.514 |

| 23. Restlessness while sitting or standing at work | 1.79 | 0.96 | 1.122 | 0.592 | 0.467 |

| 24. Feeling tired | 2.73 | 1.086 | 0.168 | −0.552 | 0.554 |

| 25. Feeling helpless | 1.8 | 0.95 | 1.21 | 1.114 | 0.583 |

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Headaches | 0.426 | 0.275 | −0.114 |

| 2. Pains and “stabbing” sensations | 0.636 | 0.144 | 0.037 |

| 3. High blood pressure | 0.423 | 0.313 | 0.197 |

| 4. Poor sleep | 0.520 | 0.257 | 0.059 |

| 6. Poor digestion | 0.462 | 0.068 | 0.097 |

| 9. Nervousness | 0.624 | 0.037 | −0.007 |

| 10. Lack of motivation, feeling depressed | 0.716 | 0.005 | 0.181 |

| 12. Changes in appetite | 0.562 | −0.010 | −0.007 |

| 13. Feeling exhausted | 0.679 | 0.079 | −0.272 |

| 16. Difficulty concentrating and maintaining attention | 0.559 | −0.077 | 0.053 |

| 17. Frequent mood swings | 0.685 | −0.081 | 0.073 |

| 18. Lack of self-confidence | 0.610 | −0.209 | 0.094 |

| 19. Excessive sweating | 0.473 | −0.081 | 0.006 |

| 20. Weakened immune system and frequent colds | 0.500 | −0.060 | −0.187 |

| 21. Taking sick leave | 0.335 | 0.080 | 0.061 |

| 22. Irritability and arguing with others | 0.540 | −0.219 | 0.055 |

| 23. Restlessness while sitting or standing at work | 0.500 | −0.309 | 0.037 |

| 24. Feeling tired | 0.621 | −0.013 | −0.386 |

| 25. Feeling helpless | 0.625 | −0.051 | 0.086 |

| Extraction method: principal axis factoring. 3 factors extracted. 20 iterations required. | |||

| M | SD | α | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Stress Symptoms | 2.08 | 0.58 | 0.89 | 1 | ||||||

| 2. Job Pressure | 2.38 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.28 ** | 1 | |||||

| 3. Lack of Support | 2.19 | 0.75 | 0.86 | 0.34 ** | 0.63 ** | 1 | ||||

| 4. Job Stress | 2.13 | 0.62 | 0.73 | 0.29 ** | 0.76 ** | 0.71 ** | 1 | |||

| 5. Intrinsic Satisfaction | 3.44 | 0.77 | 0.89 | −0.30 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.48 ** | −0.38 ** | 1 | ||

| 6. Extrinsic Satisfaction | 3.07 | 0.93 | 0.85 | −0.33 ** | −0.27 ** | −0.58 ** | −0.45 ** | 0.77 ** | 1 | |

| 7. Job Satisfaction | 3.32 | 0.77 | 0.93 | −0.34 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.55 ** | −0.43 ** | 0.96 ** | 0.91 ** | 1 |

| Predictor | B | SE(B) | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Constant) | 4.85 | 0.10 | - | 48.98 | <0.001 |

| Stress Symptoms | −0.234 | 0.04 | −0.176 | −5.92 | <0.001 |

| Lack of Support | −0.543 | 0.45 | −0.524 | −11.93 | <0.001 |

| Job Pressure | 0.250 | 0.04 | 0.231 | 5.75 | <0.001 |

| Job Stress | −0.200 | 0.06 | −0.158 | −3.35 | 0.001 |

| Dependent variable: Job Satisfaction | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jokanović, B.; Vrgović, P.; Ćulibrk, J.; Tomić, I.; Jošanov-Vrgović, I. Job Satisfaction in the Face of Organizational Stress: Validating a Stress Symptoms Survey and Exploring Stress-Related Predictors. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177843

Jokanović B, Vrgović P, Ćulibrk J, Tomić I, Jošanov-Vrgović I. Job Satisfaction in the Face of Organizational Stress: Validating a Stress Symptoms Survey and Exploring Stress-Related Predictors. Sustainability. 2025; 17(17):7843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177843

Chicago/Turabian StyleJokanović, Bojana, Petar Vrgović, Jelena Ćulibrk, Ivana Tomić, and Ivana Jošanov-Vrgović. 2025. "Job Satisfaction in the Face of Organizational Stress: Validating a Stress Symptoms Survey and Exploring Stress-Related Predictors" Sustainability 17, no. 17: 7843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177843

APA StyleJokanović, B., Vrgović, P., Ćulibrk, J., Tomić, I., & Jošanov-Vrgović, I. (2025). Job Satisfaction in the Face of Organizational Stress: Validating a Stress Symptoms Survey and Exploring Stress-Related Predictors. Sustainability, 17(17), 7843. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17177843