1. Introduction

Sustainability has become a major concern for both institutions and the public, driven by the growing awareness of climate change and environmental damage. Institutional terms such as “ESG” and “carbon neutrality” have entered public discourse as signals of long-term agendas and strategic commitments [

1,

2]. At the same time, consumer-oriented terms such as “zero waste”, “plastic-free”, and “eco-friendly” have gained popularity, reflecting a lifestyle shift toward sustainability.

Although both institutional and consumer voices shape the sustainability agenda, we know little about how these two domains are connected over time. In particular, it is unclear whether the institutional messaging delivered through governments, businesses, or NGOs influences the timing or direction of consumer interest. To address this gap, researchers have drawn on agenda-setting theory, which explains how repeated messaging by powerful actors guides public attention [

3]. Also, diffusion-of-innovations theory suggests that new ideas often emerge from central sources before spreading to broader audiences [

4,

5]. These perspectives frame the temporal dynamics of sustainability discourse, yet few studies have examined how such patterns evolve in digital environments.

Digital platforms now play a critical role in shaping public attention, and tools such as Google Trends allow researchers to track sustainability-related discourse as it develops in real time.

This study analyzes monthly Google Trends data in the United States from 2019 to 2024, focusing on five sustainability-related keywords. The terms “ESG” and “carbon neutral” capture institutionally oriented language common in policy documents, regulations, and corporate reports, whereas “zero waste”, “plastic free”, and “eco friendly” represent consumer-facing expressions. By comparing the search patterns associated with these two groups, we examine whether institutional attention tends to precede and shape consumer interest.

To analyze these relationships, we employ Granger causality tests, impulse response functions, and cross-correlation analysis. These methods capture both the direction and the timing of influence, revealing how public attention may cascade from top-down institutional narratives to bottom-up consumer engagement.

Our findings contribute to the discourse in three ways. First, this study links communication theory with time-series analysis to empirically trace the flow of sustainability discourse across domains. Second, it extends agenda-setting and diffusion frameworks to digital behavior, revealing how sustainability messages diffuse across levels of influence. Third, it offers practical guidance for policymakers, marketers, and NGOs on how to align their communication strategies with evolving public concerns.

By identifying the temporal structure of sustainability-related search behavior, this study offers new insights into the digital dynamics of environmental engagement. In doing so, it contributes to the growing field of digital sustainability analytics and opens new avenues for theory-driven, data-informed communication research.

The objective of this study is to examine whether institutional sustainability discourse, as reflected in searches for the terms “ESG” and “carbon neutral”, precedes and influences consumer-oriented interest in the “eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free” search terms. Using agenda-setting theory and diffusion frameworks with the multi-year Google Trends data, we aim to clarify the direction and timing of these flows in the U.S. context (2019–2024).

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 reviews the prior literature on sustainability communication, consumer search behavior, and digital trend analysis.

Section 3 outlines the data and methodology.

Section 4 presents the empirical findings; this is followed by a discussion of their theoretical and practical implications.

Section 5 concludes with key takeaways and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

The accelerating impacts of climate change, ecosystem degradation, and resource exhaustion have prompted growing institutional efforts to support sustainable behavior. Governments, businesses, and NGOs shape public discourse by introducing concepts such as “carbon neutrality” and “ESG”, which now appear widely in policies, corporate reports, and media coverage [

1]. These institutional signals help establish behavioral standards, legitimize sustainable practices, and influence social norms.

Key policy frameworks illustrate this process. The European Green Deal outlines a plan to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 (European Commission, 2019) [

6]. In the U.S., the ISSB Sustainability Disclosure Standards (IFRS Foundation, 2023) [

7] mandate sustainability reporting at the corporate level.

Global reports such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals Report (United Nations, 2023) [

8] and the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2023) [

9] provide widely recognized benchmarks that reinforce institutional influence across media, corporations, and public debate.

Agenda-setting theory provides a useful framework for understanding how institutions interact with public attention [

3]. The media and policy discourses amplify these signals, helping them spread more widely. The diffusion-of-innovations framework complements this view, describing how new ideas first emerge from influential actors before diffusing to broader audiences [

10]. Together, these perspectives highlight how sustainability messaging moves from institutions to the public.

Sustainability communication often combines top-down and bottom-up dynamics. Institutions advance sustainability through legislation, eco-labels, and ESG reporting, while individuals engage through consumption choices that reflect personal values. Prior research shows that sustained institutional messaging, especially when supported by credible sources, can generate long-term shifts in awareness and behavior [

11,

12]. For example, during COVID-19, regular updates from trusted authorities reinforced preventive behaviors such as mask-wearing and vaccination [

13]. Yet, the empirical relationship between institutional discourse and consumer interest remains underexplored over time.

Digital platforms now provide new ways to observe these dynamics. Google Trends is widely used to capture search data that reflect real-time public interest. Prior work has applied it to diverse fields: monitoring infectious disease outbreaks [

14], tracking health information during COVID-19 [

15], forecasting financial market volatility [

16], and studying the reliability of search-based indicators [

17]. In environmental communication, Google Trends has revealed partisan patterns in climate-information seeking [

18] and mapped climate discourse alongside social-media and survey data [

19]. This tool can detect spikes linked to events [

20], compare topic salience, and trace temporal diffusion [

21].

In sustainability studies, Google Trends has been used to examine reactions to climate summits [

20] and to track seasonal interest in environmental keywords [

21]. Most of these works, however, focus on single terms and provide descriptive insights rather than analyzing the temporal interplay between institutional and consumer concepts [

6,

22,

23]. This gap limits our understanding of whether top-down sustainability narratives translate into bottom-up engagement. Moreover, few studies explicitly link search patterns to communication or diffusion theory, leaving the mechanisms behind observed trends unclear.

Despite its potential, the use of Google Trends in sustainability research has been largely descriptive. Studies have used Google Trends to document spikes in search interest around major environmental events, sustained increases in climate-related engagement, and seasonal or event-driven patterns in environmentally relevant keywords [

6,

22,

23]. Recent work has begun to expand this scope, for example, by examining global patterns of public engagement with health and climate change using Google Trends [

24]. However, these studies typically analyze individual terms in isolation and do not investigate how institutional and consumer-facing concepts relate to one another temporally. This leaves a gap in the understanding of the directional relationships between different layers of sustainability discourse.

The distinction between institutional and consumer-oriented sustainability terms is conceptually meaningful. Terms like “ESG” and “carbon neutral” are usually introduced through formal policies, regulatory frameworks, and corporate strategies. These terms tend to be technical and focused on policy or strategy. In contrast, phrases such as “zero waste”, “eco-friendly”, and “plastic-free” are more familiar to the public. They are often connected to daily habits, consumer choices, and social or marketing campaigns. While the former reflect macro-level commitments, the latter connect to micro-level behaviors. Understanding how attention shifts between these domains over time can help bridge the gap between high-level messaging and public engagement.

Prior research efforts in areas like health and tourism demonstrate how digital data, including keyword search trends, can provide insight into shifts in public interest. For instance, health researchers have used search trends to anticipate flu outbreaks and assess the effectiveness of awareness campaigns. In tourism, similar patterns have been linked to consumer behaviors such as travel booking and seasonal demand, with studies showing that social-media engagement metrics such as Facebook page “likes” for destination marketing organizations can serve as leading indicators of tourism demand [

22]. These examples show that digital search patterns can reflect meaningful behavioral signals, especially when interpreted through the relevant theoretical lenses.

Within sustainability, however, few studies have examined whether interest in institutionally framed concepts can systematically forecast attention to behavior-oriented terms, with the existing work primarily focusing on specific domains such as energy markets [

25] or the sustainable development goals [

26]. This highlights an important gap in the evaluation of whether and how top-down sustainability narratives translate into bottom-up engagement.

Moreover, much of the existing work lacks integration with communication or innovation-diffusion theory, limiting its ability to explain the mechanisms behind observed search patterns.

To address these gaps, the present study combines theoretical grounding with time-series analysis to explore the temporal relationships between institution-driven and consumer-oriented sustainability keywords. By analyzing multi-year Google Trends data, we aim to identify directional patterns in public attention that reflect the cascading influence of institutional discourse. This approach contributes to the literature by moving beyond descriptive trend analysis and toward an integrated framework for understanding how sustainability messaging flows across levels of discourse.

Based on the theoretical perspectives and empirical gaps outlined above, we propose the following hypothesis:

H1: Search interest in institutional sustainability terms (“ESG” and “carbon neutral”) leads search interest in consumer-oriented terms (“eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free”), with a measurable time lag.

To account for differences in message complexity and public resonance, we further propose the following:

H1a: “ESG” search interest exerts a slower but more sustained influence on consumer-oriented terms.

H1b: “Carbon neutral” search interest produces a faster but shorter-lived influence on consumer-oriented terms.

3. Methodology

This study employs a quantitative time-series approach to investigate the temporal dynamics of public interest in sustainability-related topics. The analysis is based on keyword search data from Google Trends for five keywords: “ESG”, “carbon neutral”, “eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free.” These terms were selected to explore directional relationships between institutionally driven concepts and those more closely associated with consumer behavior.

Monthly Google Trends data were collected for each keyword from January 2019 to December 2024, restricted to search activity within the United States. Google Trends normalizes search volume on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating the highest level of relative interest during the selected timeframe. Keywords were selected based on three considerations: they showed sufficiently consistent search volume throughout the study period to ensure statistical reliability, had clear conceptual relevance to either institutional or consumer-oriented sustainability discourse, and were broadly familiar to the public (to enhance interpretability). All five keywords were retrieved in a single Google Trends “compare” query, restricted to the United States, to ensure normalization consistency across the series and to avoid scaling discrepancies that can occur when terms are downloaded separately. Prior to finalizing the list, each candidate term was tested in Google Trends for unrelated meanings or contexts, and any term showing substantial search activity unrelated to sustainability (e.g., homonyms, brand names) was excluded.

Each keyword trend was inspected for missing values, anomalies, and structural inconsistencies. Minimal preprocessing was applied, limited to visual inspection for outliers and alignment of series lengths. No smoothing or transformation was applied, in order to preserve the integrity of the raw search patterns. Keywords with insufficient search volume, semantic ambiguity, or irregular patterns were excluded during the initial screening process.

The five keywords represent two distinct domains of sustainability discourse. “ESG” and “carbon neutral” are institutionally oriented terms commonly found in policy frameworks, government communications, and corporate reporting. “Eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free” are more familiar to the general public and are often linked to daily habits and consumer choices. This dichotomy allowed us to explore whether institutional-level attention tends to precede or influence consumer-level search behavior over time.

Each keyword was screened to ensure adequate search volume and continuity throughout the study period. All five terms appeared regularly and showed meaningful changes across the study period, making them suitable for time-series analysis. The decision to use Google Trends was based on its proven utility in measuring public interest across a variety of disciplines, and, in certain contexts, forecasting behavioral patterns, including applications in health communication, economics, and analyses of political information-seeking behavior [

15,

16,

17].

This study centers on the United States for three reasons. First, the U.S. sustains a mature sustainability discourse encompassing both institutional narratives (e.g., ESG reporting, regulatory initiatives, and climate policy debates) and consumer movements (e.g., zero-waste campaigns, eco-friendly purchasing). Second, it offers one of the most extensive and stable datasets in Google Trends, mitigating the risks of low search volume or irregularities in smaller markets. Third, as a globally influential economy and media hub, the U.S. functions as a reference market from which sustainability narratives diffuse internationally via multinational corporations, cross-border policy exchanges, and the global media. While these advantages strengthen analytical clarity and data reliability, they also limit the generalizability of the findings, a limitation acknowledged in the Conclusion.

In addition, the use of Google Trends as a data source introduces its own limitations. Search volume reflects relative, not absolute, levels of interest, and Google’s proprietary normalization and sampling procedures may introduce unobserved biases. Search activity is also an imperfect proxy for actual attitudes or behaviors, as individuals may search for sustainability-related terms for reasons unrelated to genuine engagement, such as academic tasks or incidental exposure to news. Representativeness may be affected by demographic and geographic patterns in internet access and search engine usage, which can skew the sample toward certain populations. Moreover, Google Trends captures only public online search behavior and does not account for offline discourse, closed social-media channels, or interpersonal communication. These limitations suggest that the results should be interpreted with caution and, where possible, triangulated with other data sources such as surveys, media content analysis, or social-media text mining in future research.

To test the hypothesis regarding directional influence, we implemented three complementary statistical techniques. First, we conducted pairwise Granger causality tests to assess whether prior values of institutional keywords help predict subsequent changes in consumer-oriented terms [

27]. Optimal lags of one to three months were determined using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The selected lag length varied slightly across keyword pairs, but consistently fell within this range of 1–3 months, indicating the robustness of the directional relationships. Second, we used impulse response functions (IRFs) derived from vector autoregressive (VAR) models to evaluate the magnitude and duration of influence [

28]. These functions simulate the effect of a one-standard-deviation increase in institutional keyword searches on subsequent consumer search trends, offering insight into how attention diffuses over time. Third, we calculated cross-correlation coefficients to examine the degree of synchronization between institutional and consumer keyword pairs, identifying the lag structure at which correlation is maximized.

This combined approach offers a comprehensive view of how sustainability discourse unfolds over time. Granger causality allows for directional inference, IRFs illustrate dynamic responsiveness, and cross-correlations capture overall alignment. This triangulation enhances the robustness of the analysis and aligns with recommendations to move beyond purely descriptive trend studies by embedding theoretical frameworks into time-sensitive statistical models.

To minimize the risk of spurious causality caused by shared periodicity or strong autocorrelation, each keyword series was seasonally adjusted prior to Granger causality testing. The recurring annual component was removed using STL decomposition (see

Supplementary Figures S1–S3 for full decomposition results), yielding seasonally adjusted residuals. The augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test was then applied to verify stationarity, and first differencing was used where unit roots were detected, to meet the stationarity requirement of the VAR model. The optimal lag order for both the Granger causality tests and the VAR model was determined by comparing the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) values, and selecting the lag that minimized both criteria while ensuring that model residuals exhibited no significant autocorrelation. All causality tests were conducted on these preprocessed series to ensure that the detected relationships reflect genuine temporal dependencies rather than artifacts of seasonality or persistence.

To make sure the VAR-based impulse response functions were reliable, we checked the necessary conditions before running the models. We first applied ADF and KPSS tests to each keyword series and differenced the data when they showed non-stationarity. When the Johansen test suggested cointegration between non-stationary series, we also estimated vector error correction models (VECMs) to verify that any long-run linkages did not distort the short-run impulse responses. The IRFs we report are based on stationary VARs, and the results were consistent when using VECMs, giving us confidence that the main conclusions do not depend on the model specification.

By integrating these methods, the study aims to uncover meaningful temporal structures in the way public attention shifts between institutional and consumer-oriented sustainability concepts. This methodological design contributes to both empirical understanding and theoretical discussions on agenda-setting, innovation diffusion, and digital public engagement with sustainability. It is important to note that Granger causality in this study is used in the econometric sense to indicate predictive temporal precedence, rather than definitive causal mechanisms. While useful for detecting directional relationships, this approach does not establish causality in the strict philosophical sense, and the results should be interpreted as being indicative of predictive associations that may merit further investigation using complementary causal inference methods.

4. Results

We analyzed the temporal dynamics between institution-oriented and consumer-oriented sustainability keywords, using monthly Google Trends data from 2019 to 2024. Employing Granger causality tests, impulse response functions (IRFs), and cross-correlation analysis, we assessed whether institutional discourse, captured through searches for “ESG” and “carbon neutral”, preceded and influenced consumer search interest in terms such as “eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free”.

4.1. Descriptive Trends in Sustainability Searches

Figure 1 displays the temporal evolution of public search interest for the five selected sustainability-related terms. The institutionally oriented keywords, namely, “ESG” and “carbon neutral”, show a relatively low level of activity before 2020 but rise sharply and consistently starting in mid-2020. This surge aligns with the expansion of corporate ESG reporting, the occurrence of major global climate summits, and the introduction of regulatory frameworks such as the EU Taxonomy and the SEC’s proposed climate disclosure rules [

29].

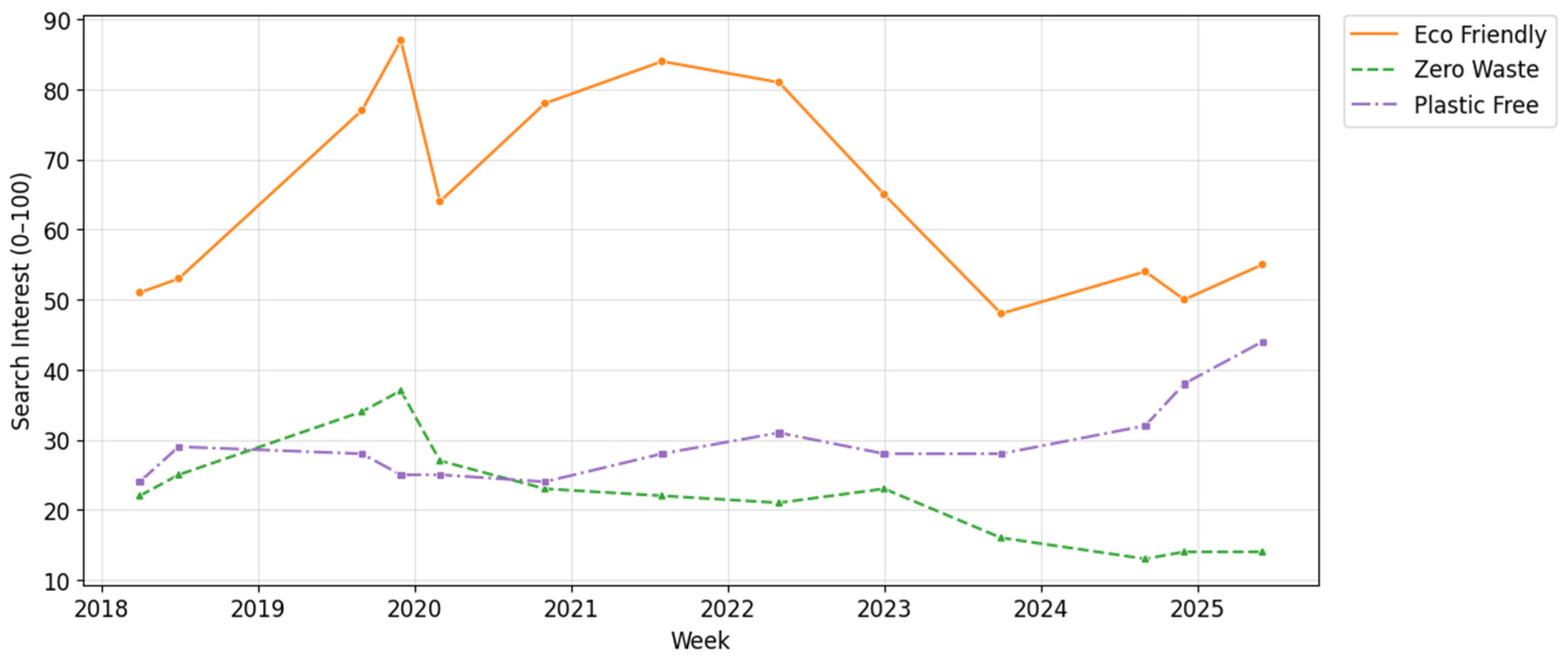

In contrast, consumer-facing keywords like “eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free” display more cyclical patterns, along with noticeable spikes in April, likely reflecting increased interest around Earth Day [

30], as well as during periods of heightened climate-related media coverage.

In addition to the overall descriptive trends shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 displays the weekly Google Trends series for the three consumer-oriented keywords (“eco friendly”, “zero waste”, and “plastic free”). Recurring seasonal upticks are visually apparent; the formal seasonal components extracted via STL are reported in the

Supplementary Materials (Figure S1), confirming the presence of annual cycles. Together,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 highlight regular peaks and seasonal cycles.

Table 1 presents summary statistics for each term. To ensure consistency between figures and summary statistics, all descriptive values in

Table 1 are computed from the Google Trends export used to plot

Figure 1, which applies a single normalization across the five terms within a joint query for 2019–2024 (U.S.). The consumer-oriented keywords exhibit higher variability. For instance, “eco friendly” has the highest mean search score (Mean = 26.98) and the largest standard deviation (S.D. = 10.83), suggesting periodic surges in public interest. In contrast, “carbon neutral” and “ESG” show lower mean values and show more stable patterns over time, reflecting a gradual institutional uptake. This divergence supports our categorization of these terms into institutional and consumer dimensions.

4.2. Granger Causality: Directional Relationships

Table 2 presents the results of Granger causality tests. “ESG” was found to predict changes in “zero waste” and “eco friendly” search interest, with

p-values of 0.035 and 0.024, respectively. “Carbon neutral” significantly predicted “zero waste” across one- to three-month lags (

p < 0.01). These results indicate that institutional search interest systematically precedes consumer-oriented interest.

Some keyword pairs also exhibited bidirectional relationships. For example, “zero waste” not only responded to institutional terms but also predicted changes in “plastic free” and even “carbon neutral”. This suggests the presence of reciprocal dynamics, in which consumer attention can reinforce or amplify institutional discourse. As described in the

Section 3, when the Granger causality analysis was repeated using seasonally adjusted and, if necessary, differenced series, the bidirectional relationships between certain keyword pairs remained statistically significant at the 5% level. This robustness check indicates that these relationships are unlikely to be driven solely by shared periodic patterns or autocorrelation.

These findings reveal a consistent temporal structure in which institutional attention tends to lead, followed by corresponding shifts in consumer engagement. While causality in the strictest sense cannot be confirmed, the statistical directionality provides evidence of sequential attention dynamics.

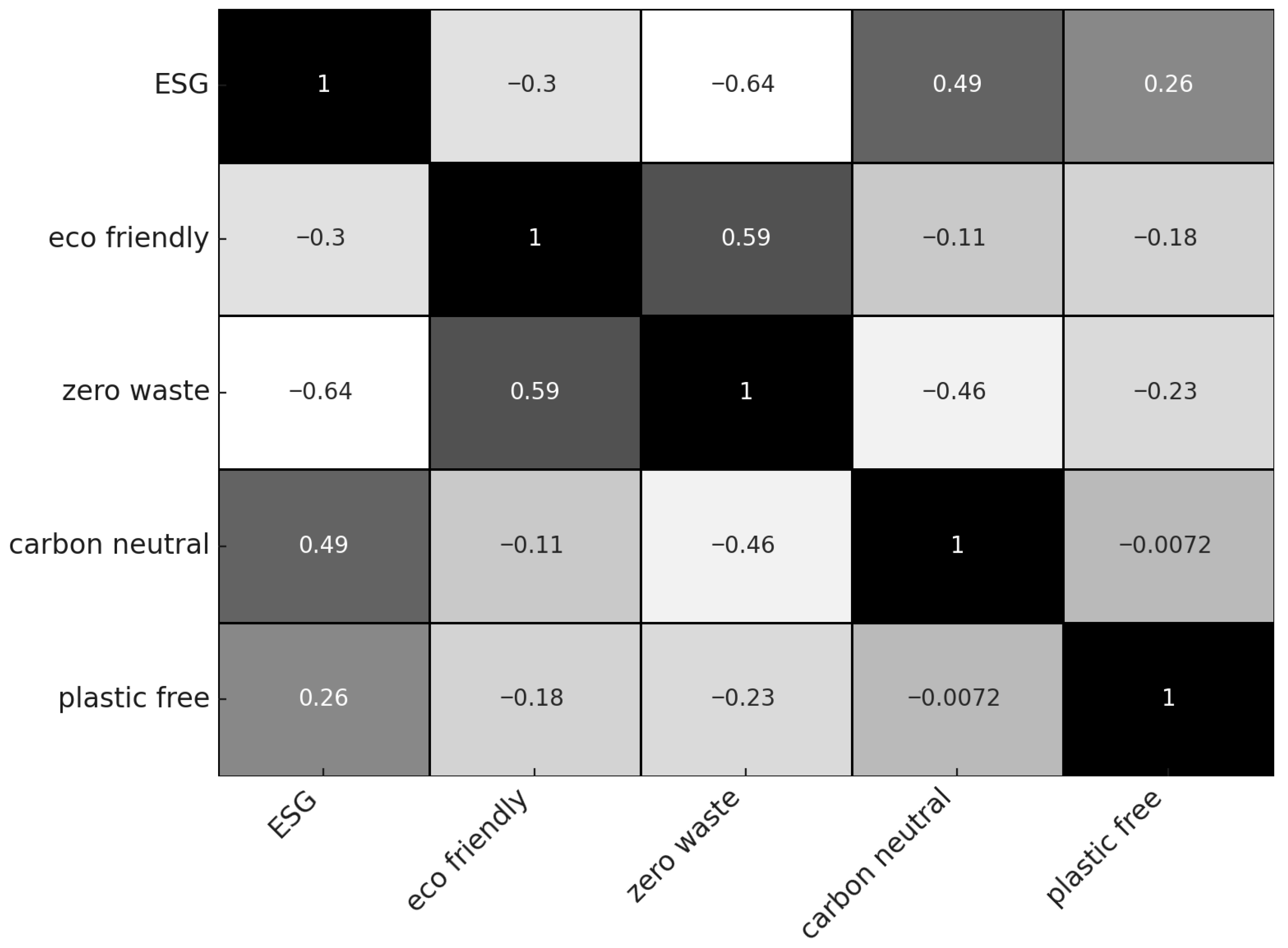

4.3. Cross-Correlation Analysis: Temporal Alignment

Figure 3 presents the standardized cross-correlation matrix for the keyword pairs. Strong positive correlations were observed between “carbon neutral” and “eco friendly”, and between “ESG” and “zero waste”, particularly at lags of one to two months. These patterns suggest that institutional keywords tend to lead consumer interest, with a measurable delay.

Some pairs, such as “ESG” and “plastic free”, showed weaker correlations, indicating that influence may vary depending on conceptual proximity and public familiarity with the terms.

Cross-correlation analysis revealed that the strongest associations emerged between “carbon neutral” and “eco friendly” and between “ESG” and “zero waste”, with coefficients exceeding 0.70 at lags of one to two months. By contrast, contemporaneous correlations (lag 0), as shown in

Figure 3, are weaker or even negative, underscoring the importance of considering temporal dynamics rather than only simultaneous relationships. This temporal lag suggests that consumer attention tends to adjust to institutional narratives with a slight delay, highlighting the role of institutional discourse as an early signal for shifts in consumer interest.

These findings offer insight into how public attention propagates across related sustainability concepts. For example, a rise in searches for “carbon neutral” is often accompanied by an increase in interest in “zero waste” or “plastic free”, suggesting that these topics are not only thematically linked but also temporally bundled in the public consciousness. This bundling effect implies that institutional concepts may act as triggers that stimulate broader engagement with individual sustainability practices.

On the other hand, some keyword pairs displayed weaker or less-immediate associations. In particular, the correlation between “ESG” and “plastic free” was relatively modest, implying that the influence of institutional terms may vary depending on their semantic closeness to consumer concerns or their prominence in public discourse. These variations highlight the importance of message framing and policy visibility when aiming to generate consumer engagement through institutional communication.

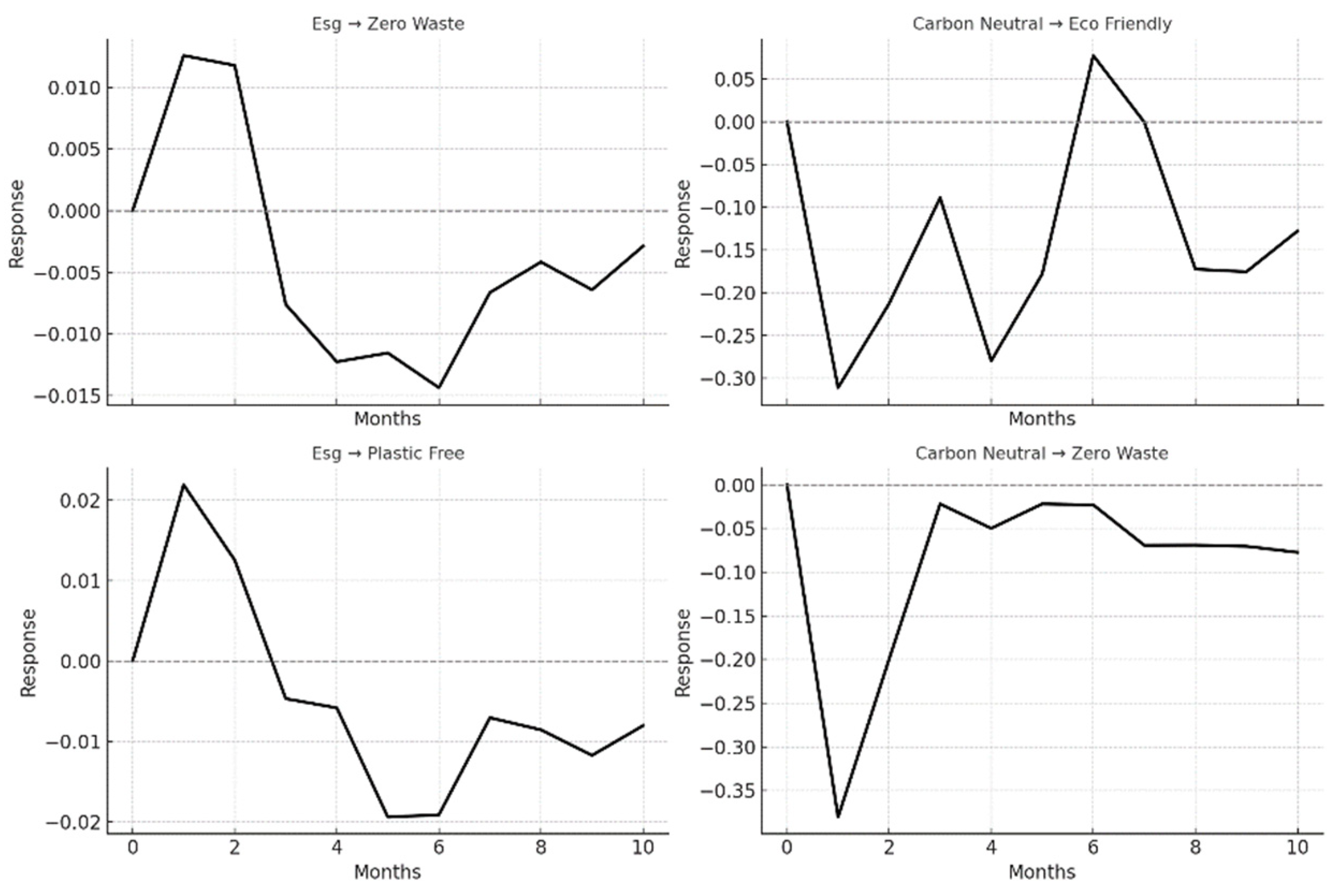

4.4. Impulse Response Functions

To assess the magnitude and duration of influence between institutional and consumer-oriented sustainability terms, we estimated impulse response functions (IRFs) based on vector autoregressive (VAR) models. These models simulate the response of one variable to an exogenous shock in another, allowing us to visualize the temporal diffusion of attention across keyword categories. Specifically, we examined how a one-standard-deviation increase in institutional keyword search interest affects subsequent changes in consumer-related search terms.

Figure 4 displays the response curves for selected keyword pairs. A simulated positive shock in “ESG” led to a gradual and persistent increase in “zero waste” search interest. The effect peaked in the second month following the initial impulse and remained elevated for approximately four months. This suggests that public engagement with “ESG” is associated with a relatively delayed but sustained downstream effect on consumer-oriented sustainability behavior. The long-lasting influence of “ESG” may reflect its complexity as a governance framework that requires interpretation, dissemination through the media and various organizations, and eventual integration into consumer consciousness.

In contrast, the IRF for “carbon neutral” or “eco friendly” searches revealed a more immediate but short-lived effect. Following a spike in “carbon neutral”, there was a sharp increase in “eco friendly” searches during the first month, followed by a rapid decline back to baseline. This pattern suggests that terms with clear and goal-oriented meanings such as “carbon neutral” may generate faster public reactions but have a shorter influence window. The immediacy of the response may be due to frequent exposure through news reports, brand campaigns, or product-level messaging, which are easier for individuals to interpret and act upon.

These varying temporal patterns reflect core attributes of institutional messaging. ESG represents a broad and multi-dimensional framework that encompasses environmental, social, and governance dimensions, typically embedded in corporate disclosures and regulatory contexts. Its diffusion into public awareness may require interpretation by sources that help to explain complex terms, such as the news media, public campaigns, or familiar companies. On the other hand, “carbon neutral” is a more specific and action-oriented term, and often tied to measurable outcomes or pledges by individual companies. As a result, it may translate more directly into consumer awareness and immediate online search activity.

The IRF results also support the broader hypothesis of a staggered and directional attention flow in sustainability discourse. Institutional terms may trigger a gradual process that influences consumer interest over time, shaped by how visible the message is, how familiar the language sounds, and how important the topic appears to be to the public. This layered structure of influence has implications for both research and practice. For researchers, it underscores the need to consider time lags and conceptual hierarchies in the analysis of digital attention data. For practitioners, it highlights the importance of aligning sustainability communication strategies with the expected timing of public responses.

Taken together, the impulse response analysis complements the Granger causality and cross-correlation results by providing a dynamic visualization of how institutional discourse translates into consumer-level engagement. Rather than producing isolated bursts of interest, institutional signals appear to initiate wave-like patterns of attention that vary in strength, timing, and persistence, depending on the nature of the initiating term.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

This study examined the temporal dynamics of sustainability-related search behavior, using Google Trends data for five keywords over five years. The results show a clear lead–lag structure: institutional terms such as “ESG” and “carbon neutral” consistently precede consumer-oriented terms like “zero waste”, “plastic free”, and “eco friendly.” Granger causality tests, impulse response functions, and cross-correlation analyses confirm that institutional discourse predicts subsequent consumer engagement.

From a theoretical perspective, our findings extend agenda-setting theory to the digital sphere. They align with earlier studies showing that digital data capture two-way interactions between traditional and social media [

31], that legacy media continue to shape public opinion even as corporate social channels expand [

32], and that factors such as networked dynamics and multiple overlapping agendas have become central in today’s media environment [

3].

The distinction between “ESG” and “carbon neutral” highlights how different institutional messages spread through public awareness. ESG, as a broad governance and reporting framework, has influenced consumer search behavior more slowly but with greater persistence, which is consistent with evidence that strong ESG performance can create lasting competitive advantages [

33]. Although interest in ESG searches fell after its 2022–2023 peak, this decline likely reflects fewer event-driven triggers and the mainstream adoption of ESG principles, rather than waning public commitment. Research also indicates that transparent, high-quality ESG disclosures strengthen brand credibility and consumer purchase intentions [

20], suggesting that consistent ESG communication supports long-term engagement. By contrast, “carbon neutral”, a more concrete and measurable term, generated faster but shorter-lived effects. These patterns underscore the importance of message framing, complexity, and alignment with consumer values in sustainability communication.

The practical implications are clear. For policymakers, knowing the timing of sustainability attention can help them schedule campaigns or regulatory announcements at times when public responsiveness is highest. For marketers and NGOs, the monitoring of institutional signals provides early insight into upcoming waves of consumer interest, supporting proactive planning, product positioning, and alignment with shifting consumer values [

32]. The periodicity analysis also shows that consumer-oriented sustainability interest follows regular annual cycles, with peaks often tied to events such as Earth Day in April or Plastic-Free July. These patterns present strategic opportunities for targeted engagement.

Although our analysis identified statistically significant directional relationships between institutional and consumer-oriented keywords, these results should be understood as predictive associations rather than definitive causal mechanisms. Unobserved factors such as media coverage, economic cycles, or major events may also shape the observed patterns [

21]. For instance, global disruptions like the COVID-19 pandemic, high-profile climate summits (e.g., COP meetings), or economic downturns could temporarily amplify or dampen public attention relative to sustainability topics, independent of the institutional discourse. While these influences were not directly modeled here, recognizing their potential roles is important for interpreting the findings and for designing future research. Studies that apply Bayesian causal reasoning or counterfactual modeling could yield stronger evidence for causal pathways, but such approaches require richer datasets and experimental designs that extend beyond the scope of this study.

While the findings provide useful insights, the study has several limitations. The analysis is restricted to the United States, selected for its mature sustainability discourse, reliable Google Trends data, and central role as a global economy and media hub. These features make it a strong case for examining the mechanisms under study, but the narrow focus also limits the generalizability of the results to other cultural or policy settings. Future research could expand the framework to cross-national comparisons, testing whether similar lead–lag patterns appear in countries with different institutional structures, sustainability policies, and consumer behaviors. Recent studies have already begun to extend digital sustainability analytics to broader climate change discourse by using Google Trends [

20], suggesting opportunities to situate institutional–consumer dynamics within global comparative settings. Further work might also draw on additional data sources, such as social-media sentiment, online news coverage, or survey-based measures of environmental concern, as well as keywords linked to specific industries (e.g., “sustainable fashion”) or emotional framing (e.g., “climate anxiety”).

In conclusion, this study contributes to the emerging field of digital sustainability analytics by revealing how institutional discourse diffuses over time and shapes consumer interest in measurable ways. The results show, for example, that “ESG” predicts “eco friendly” searches with a three-month lag (p = 0.024) and “zero waste” with a one-month lag (p = 0.035), while “carbon neutral” predicts “zero waste” across one- to three-month lags (p <0.01). The strongest cross-correlations (above r = 0.70) appeared between “ESG” and “zero waste”, and between “carbon neutral” and “eco friendly”, with effects most pronounced at one- to two-month lags. Impulse response analysis further revealed that ESG effects persisted for roughly four months, whereas carbon neutral effects were immediate but short-lived, returning to baseline within one month.

These results also highlight important conceptual distinctions. “ESG”, as a complex and multi-dimensional governance framework, diffuses more slowly but with longer-lasting effects, reflecting its institutional anchoring in corporate reporting and regulatory debates. By contrast, “carbon neutral”, a concrete and action-oriented goal, produces rapid but short-lived attention spikes, often tied to specific campaigns or events. In addition, some bidirectional dynamics emerged: for example, “zero waste” was found to Granger-cause “carbon neutral”, suggesting that consumer discourse can reinforce or reshape institutional agendas. This reciprocal influence indicates that sustainability communication is not purely top-down, but shaped by feedback loops between institutional and consumer narratives.

These empirical patterns provide a concrete basis for the theoretical and practical implications discussed above. By integrating time-series methods with communication theory, this study offers a structured, data-driven view of how sustainability attention spreads through the digital public sphere. As environmental messaging grows in both volume and speed, understanding these diffusion patterns is critical for designing strategies that resonate with the public and foster lasting behavioral change.