1. Introduction

Architecture and construction play a significant role in cities’ material cultural heritage. Townhouses, in particular, characterise the urban landscape, filling the streets and squares of historic centres with their façades. Architectural heritage is also a visual expression of intangible values, such as the skills and traditions associated with architecture and construction. Without knowledge passed down from generation to generation, parts of buildings would be at risk of becoming impossible to conserve or reconstruct.

Architectural heritage is an excellent tool for shaping the place’s identity. Residential architecture is the most prevalent form of urban development and has great potential to highlight a city’s unique characteristics [

1]. The consistent use of traditional building techniques and decorations, the revitalisation of historic buildings and the creation of modern buildings based on historic motifs can create attractive places for tourists and the local community. This can help to revitalise depopulated towns or neighbourhoods, create jobs and prevent the allochtonisation of residents.

However, despite its high cultural, social and economic value, this part of the architectural heritage is often inadequately protected and utilised. In order to maintain the relevance of historic residential architecture in changing socio-economic conditions, mere repairs to building façades are insufficient. Traditional construction methods must be combined with modern technologies to allow housing to adapt to the requirements of modern society without losing its historic substance and uniqueness. This approach creates a continuation of tradition rather than an obliteration of it. For this to happen, the public must understand the cultural value of their surrounding buildings and how these can be adapted to meet modern requirements.

1.1. Research Aim and Hypothesis

The study aimed to demonstrate the value and potential of residential buildings that form a distinctive cityscape, highlighting their importance as part of the architectural and cultural heritage and their potential to identify the city. Using selected city centres as examples, the study examined whether unique, traditional and uniform residential buildings filling the streets and squares can carry historical and social-cultural values and whether they can distinguish the city from others.

Another research problem that was addressed was the impact of multifaceted, interdisciplinary activities on revitalisation outcomes. The research emphasised the importance of considering various factors to preserve the distinctiveness of historic buildings while addressing the requirements of contemporary communities. The actions taken for each of the described examples varied and were tailored to local needs.

The importance of protecting intangible heritage, such as the ability to perform traditional building and artistic crafts, was also emphasised, as was the need to educate young people in these areas. Additionally, the importance of educating local communities and ensuring their participation in all decision-making processes was also emphasised. Only sustainable actions in cultural, social, economic, architectural and urban planning fields, preceded by thorough research and public consultation, can produce a positive and lasting effect on future generations.

The following research hypotheses were put forward:

Tenements, being the most numerous form of urban development, constitute an important element of cultural heritage.

Tenements with common and homogeneous features shape the identity of a city and have great potential to create a specific sense of place.

Irrespective of a city’s size, age or functions, consistent use of traditional building or decorative techniques, revitalisation of historic residential buildings and creation of modern buildings based on their motifs help maintain urban landscape homogeneity.

Residential architecture with homogeneous features can be an excellent identifier of a city.

The findings of the research described below confirmed these hypotheses using selected examples.

1.2. Literature Review

There is a wealth literature on urban regeneration, identity formation and cultural landscapes, covering a wide range of topics. For this reason, the literature review only included items that were relevant to the issues addressed in the article. These items were organised from general issues to specific studies on residential architecture. Additionally, legal acts, local conservation studies and press articles were relevant to the research. For the case studies, it was necessary to refer to studies on the selected centres, which are included at the end of the relevant subsection.

Researchers have considered the meaning of the term “identity” itself, which can be understood and addressed in a variety of ways [

1,

2]. The necessity to devise indicators for measuring place identity was also highlighted, with a view to establishing a shared reference point. These issues were raised by Paulina Dudzik-Deko and Joanna Rzeźnik, among others, describing various research methods and creating their own indicator for measuring place identity [

3]. Cultural architectural heritage has been the subject of interdisciplinary reflection at the boundaries of various academic disciplines, as evidenced by the collective study “Cities’ Identity Through Architecture and Arts”, the aftermath of a conference in which architecture and the arts were discussed as factors influencing urban identity [

4].

The revitalisation of urban areas and the protection of architectural heritage are important tasks for local and regional authorities. This area encompasses a wide range of activities, issues, problems and proposals for solutions [

5]. Also related to architectural heritage is the branding of the city, widely described by researchers such as Beatriz Casais and Patrícia Monteiro [

6]. Often, city-building involves integrating the historic urban fabric into the process of shaping a sustainable city [

7]. A considerable number of researchers have considered the above issues using examples of specific cities or comparing activities in several centres. An interesting study of architecture as a factor in city identification using Barcelona and Boston as examples was conducted by Candace Jones and Silviya Svejenova [

8]. The issue of typological studies in the aspect of revitalisation of traditional architecture in Alentejo, Portugal, was addressed by Anna Rosado and Miguel Reimão Costa [

9]. Few researchers have been involved in the study of the issue of residential architecture as a factor that can shape the cityscape and be a distinguishing feature of the city. Examples of such research include works on the cities of Herat [

10], Erbil—focusing on the impact of building form and function on identity continuity [

11]—and Izmir—examining the potential of housing estates [

12].

All of the studies, which dealt with various aspects of architectural heritage, provided an overview of the heritage issues in the selected centres, their characteristic landscapes and methods of revitalisation, including the Granada Convention and UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape. (HUL).

The literature on the selected centres and the typology of residential architecture, including construction methods and decorative elements, played a significant role in the research. Of the many studies on framework architecture, it is worth citing the one devoted also to Alsfeld [

13]. An important position on timber frame architecture in various aspects is the collection of studies Gebäude aus Fachwerk Konstruktion–Schäden–Instandsetzung [

14].

The second centre chosen for detailed research is Segovia, with its buildings covered in sgraffito. A great deal of research has been conducted into the history of this decorative technique; for example, see the work of Alonso Ruis [

15,

16]. There has also been a great deal of research on the historic architecture of Segovia and its unique façade decoration [

17,

18,

19,

20]. It is necessary to mention the most important studies by the Segovia sgraffito expert Alonzo Ruiz [

21,

22,

23].

Another city chosen as a case study is Porto. The traditional architecture of the centre and the problems of revitalisation have been studied by, among others Hugo Santos, Paulo Valença and Eduardo Oliveira Fernandes [

24] and Joaquim Teixeira, Rui Fernandes Póvoas [

25]. Joaquim Flores addressed the energy efficiency problems of buildings in Porto [

26].

The final seaside resort to be investigated is Binz, which has not been the subject of many studies. Spa architecture was the subject of a book on Barbara Finke i Beatrice Pipia “Landhäuser & Villen am Meer-Rügen und Hiddensee”. Binz architecture is mentioned in an article by Joanna Arlet on the development of resort buildings in Pomerania [

27]. Use of wood in the Baltic architecture as exemplified by Binz in Rug, is described in the article “Use of wood in the Baltic courses architecture on the example of Binz in Ruges” [

28].

A number of conservation studies, reports, municipal and regional documents and ordinances, as well as municipal and private websites and the local press, greatly aided the research.

1.3. The Value of Unique, Residential Architectural Ensembles in the Modern World

It seems obvious that places with peculiar features and unique architecture should be revitalised, brought up to modern standards, and that skills and training in traditional building trades should be imparted. However, in an age of globalisation and virtual reality, the spaces around us are becoming increasingly homogenised. Historic buildings, especially residential ones, which are often not considered particularly valuable, are deteriorating or being demolished, thereby losing their historic value. Modern residential architecture rarely identifies a place, especially in smaller provincial towns. Residential neighbourhoods built in the 20th or 21st century, regardless of region, tend to be similar and lack a distinct identity. Therefore, studying places where this identity exists and a sense of “genius loci” is present is necessary for preserving the traditions and “roots” of local communities, the diversity of the architectural landscape and sustainable development.

It remains relevant to investigate the factors and activities that favour the preservation of local identity, the historical context of places where this preservation occurs and the methods by which a balance between tradition and modernity is achieved. Identifying successful examples, particularly with regard to the revitalisation of distinctive local housing, is helpful in caring for architectural heritage. Such studies also demonstrate the various opportunities that caring for cultural architectural heritage can offer local communities, such as improved housing conditions, tourism development, job creation, improved communication and more. Examples of the restoration of intangible heritage, such as the training of craftsmen and companies operating using traditional techniques, are also valuable. Additionally, showcasing the collaborative efforts of local communities in revitalisation projects, fostering their creativity and satisfaction with the impressive outcomes, can inspire similar initiatives in other locations. Nevertheless, there is still much to be done in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

The study focused on urban centres that had diverse functions, were located in different places and had distinctive local and traditional residential architectural features that characterised the urban landscape. Various revitalisation activities took place in these centres. These included the German cities of Alsfeld and Binz, the Spanish city of Segovia and the Portuguese city of Porto.

The study deliberately selected cities whose landscape and identity were shaped by heterogeneous factors. The only feature these centres had in common was their interesting and distinctive residential architecture. It is important to highlight these differences in order to demonstrate the various possibilities for urban revitalisation and the different approaches to identifying the factors that shape the identity of cities. This also serves to emphasise the value of residential architecture itself, which is often underestimated and overlooked.

In line with the research hypothesis, urban centres were selected for the study:

Of diverse functions, geographical locations, sizes and histories (including the “age of the city”);

With strongly distinctive local traditional residential architectural features that are different in each town and characterise the urban landscape;

In which various revitalisation activities have been carried out.

After preliminary research in various regions of Europe, the following cities were selected: Alsfeld and Binz in Germany, Segovia in Spain and Porto in Portugal. The authors also considered French cities such as the summer town of Cabourg, with its villas reminiscent of Norman architecture and Arts and Crafts grouping style, or Troyes with its tall, up to four-storey half-timbered houses, erected consistently since the 16th century. However, the peculiarities of French towns and the constraints imposed by the form of publication meant that centres from that country were left for further study.

The selected towns were analysed in the context of their history, building traditions and the specifics of the revitalisation measures undertaken. In situ research was conducted in each town, involving an architectural and photographic survey and the collection of a database for further analysis. This process allowed us to identify the unique features of the residential buildings in the selected cities, as well as the extent to which these features influence the urban landscape. Comparative morphology was applied to create classifications and typologies of the specific features of the selected examples. The literature was then analysed in a historical context, taking into account the history of the cities and regeneration efforts. Furthermore, nomothetic analysis identified which steps contributed to the successes achieved. A summary of the research was presented in the form of case studies.

3. Analysis of the Case Study

3.1. Alsfeld—Half-Timbered European Model City

Alsfeld is a small town in Hesse whose history dates back to the turn of the eighth and ninth centuries. It was already a significant urban centre by the 13th century. It thrived on the production and sale of cloth. Alsfeld’s golden age came in the 16th century. During this period, many burgher houses were built in the distinctive timber-frame style, many of which remain standing today. However, the town’s development came to an end with the Thirty Years’ War and the destruction it brought. The subsequent crisis, which lasted until the end of the 19th century, and the city’s delayed industrialisation meant that its historic architecture and urban layout were preserved from its heyday [

29,

30].

Today, Alsfeld is considered a model city thanks to its half-timbered buildings. It contains around 400 half-timbered houses built between the 14th and 19th centuries. These bourgeois timber-framed houses dominate the town’s landscape, building up its identity. This technique is a traditional way of building in Hessen, but the number of preserved buildings, almost entirely filling the streets of Alsfeld, sets the town apart. Thanks to a centuries-old building tradition that has been preserved for centuries, it is possible to trace the development of timber construction here from the late Middle Ages to the 19th century [

31] (

Figure 1).

What they have in common is not only construction technology but also similar dimensions and roof forms. The individual houses are distinguished by the colours used and the woodcarving decorations, from friezes of various forms, columns to sculptures of high artistic value. On the pile caps of many houses, inscriptions can be found, usually indicating who built the building or lived in it and when. As shown in

Figure 2, on one of the most interesting houses, belonging to the master baker Jost Stumpf (Markt 6, erected in 1609), an inscription reads the following: “This is the richest decorated house in Alsfeld”. In

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the colourful townhouses create a unique character for the city’s buildings, its identity, demonstrating the cultural value of the architectural heritage as well as influencing social and economic development (

Figure 5).

In addition to its architectural heritage, Alsfeld has a pioneering tradition of historic preservation dating back to 1878 when the townspeople protested against the demolition of the town hall. This was followed by the enactment of a local building statute (Ortsbau-Statut) in 1900, supplemented two years later by the Law on the Protection of Monuments. At the beginning of the 20th century, the half-timbered houses were renovated and their construction exposed, generating considerable interest in the town [

31]. The town did not suffer significant damage during the Second World War, and work to protect its monuments continued after 1945. In 1963, councillors passed a new town charter which stated the following: “The historic centre of the district town of Alsfeld is a magnificent monument of medieval and Renaissance architecture, which has happily survived to the present day. The preservation and maintenance of the old townscape is therefore a special duty of the municipal authorities”. As a result of many years of revitalisation efforts, Alsfeld has held the title of “European Model City for Historic Preservation” since 1975, which has helped the city to become internationally recognised [

32]. Unfortunately, subsequent conservation efforts have not always been appropriate, leading to structural damage to the buildings.

Efforts to protect the historic centre of Alsfeld did not resume until 2016. Based on previous experiences, an integrated urban development concept was created, taking into account very broad measures in the cultural, social and economic fields. The result was the construction of a modern urban regeneration plan, providing an impetus not only for the renovation of the historic building fabric but also for the development and strengthening of the old town as a residential and commercial location [

13,

33]. The implemented measures have produced good and lasting results, affecting both the state of the cultural heritage, the place’s identity and the city’s coherent, sustainable image [

34].

Alsfeld is a unique example of a city with a long tradition of historic preservation. While not all past measures were successful in the past, lessons were learned and mistakes were not repeated. Thanks to the implementation of a new, comprehensive, interdisciplinary programme for preserving the historic centre—which includes measures that go far beyond protecting monuments—Alsfeld today boasts a unique townscape of beautifully maintained, homogeneous buildings.

3.2. Segovia—The Sgraffito Tradition—Diversity in Unity

Segovia’s origins are linked to a Celtic settlement which was conquered by the Romans in 80 BC (more on the history of Segovia among other things [

18,

35]). The city subsequently came under the rule of the Visigoths, followed by the Moors, who both left their mark on the local culture. In 1079, it was conquered by King Alfonso VI, becoming a Christian city once again. By the end of the 16th century, Segovia had experienced rapid growth, becoming wealthy through wool production and trade. However, after a plague epidemic in the following century, the city experienced a period of depopulation and economic decline. It was not until the second half of the 19th century that a renewed period of economic and demographic revival occurred.

The tradition of using sgraffito in Segovia dates back to the 15th century (

Figure 6), and it has continued to be used and adapted to meet current needs ever since. In this way, sgraffito became a unifying element in the architecture of Segovia, influencing the design of façades on buildings constructed during different historical periods. In the 17th century, the economic crisis led to a decline in the technical level of private building, resulting in the deterioration of masonry and the deterioration of the appearance of the buildings [

20]. In 1856, the town councillors addressed the issue of cleaning up the buildings and repairing the façades [

36]. Among the façades restored in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries, those covered with sgraffito were the best. As early as 1910, Francisco de Alcántara wrote of the “plaster of Segovia”: “…, although it is not exclusive to Segovia, most of the old specimens can be found here and it is still used as a durable finish with different decorations patterns” (

Figure 7) [

37].

The historic centre of Segovia is distinguished by the unique “lace” design of its buildings’ façades. This effect is created by covering the façades with geometric, artistic sgraffito. Eminent Segovia sgraffito expert Rafael Ruiz called it “la piel de Segovia”—the skin of Segovia [

38]—highlighting the widespread use of this technique and its influence on the cityscape. This is a prime example of an ever-living tradition, influencing considerable architectural integrity and stemming from the city’s interesting multicultural history.

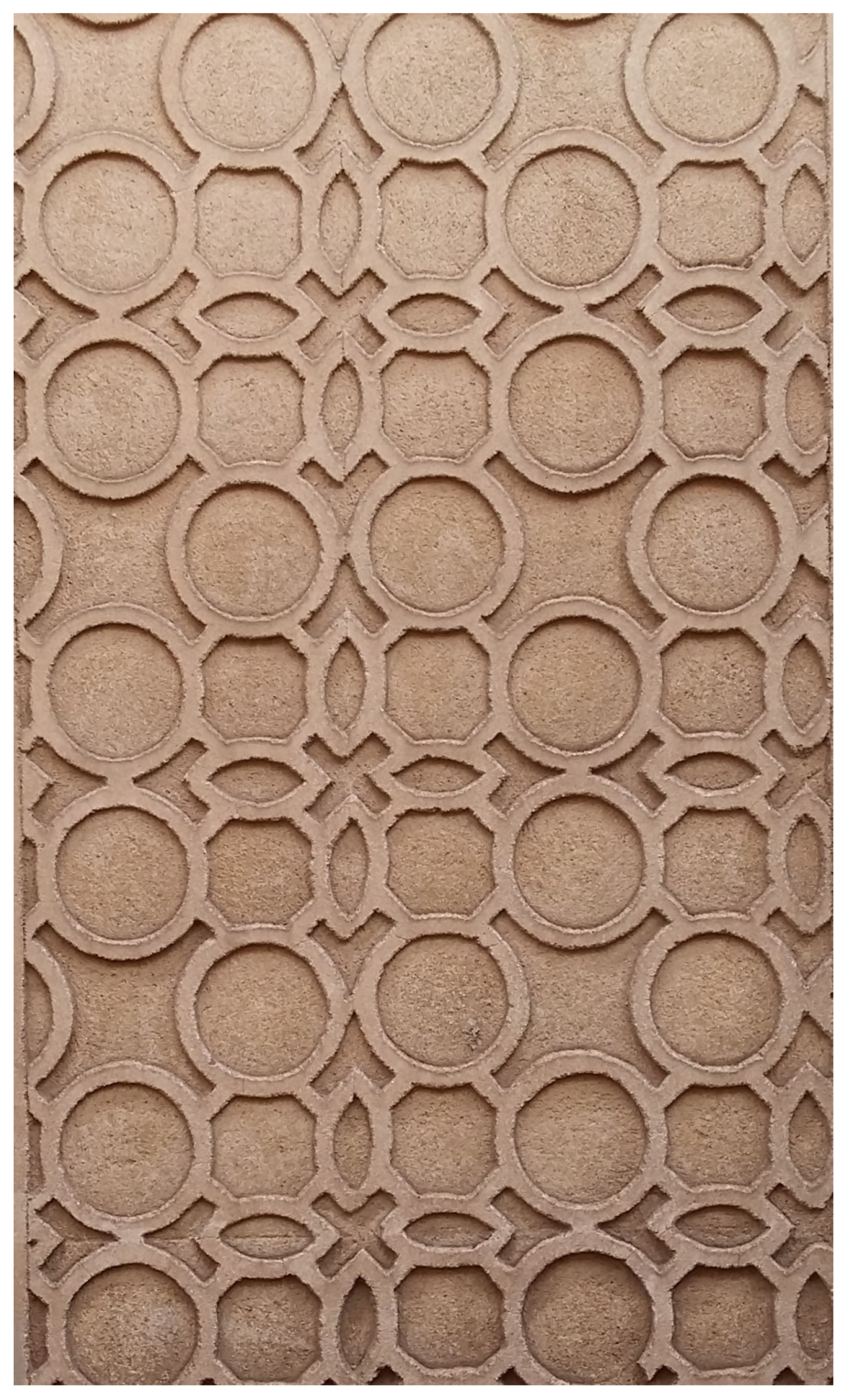

By analysing the forms of decoration found on residential building façades, it is possible to observe their evolution, from irregular shapes reminiscent of a drop of water to circles and fragments of circles, variously distributed between them, other geometric figures, stylised floral forms—tendrils, rosettes and fish bladders. In Segovia alone, 169 different models were found, and as many as 664 in the whole province [

20]. The most numerous group consists of sgraffito with geometric ornaments, created using stencils in the 19th and 20th centuries (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10).

Differences can also be seen in the layout of the sgraffito decorations on the façades of the individual buildings (

Figure 11). The depth of the relief was another important factor, affecting the chiaroscuro and plasticity of the façade. A similar role was played by the colour contrast of the individual plaster layers. The variety of Segovian sgraffito was also influenced by the use of different technical variants, such as embossed and scratched sgraffito, consisting of two or more layers made with different materials and different tools. Finally, different stencils were used, for example made of metal or stone [

21]. The similarity of forms and the few surviving examples of Islamic sgraffito suggest the influence of Islamic art [

17,

22].

Most of the historic buildings have been catalogued as part of the valorisation of Segovia’s historic centre in a multi-volume catalogue, part of a report on sustainable urban development [

39]. In order to preserve this traditional craft, in 1985, the School of Applied Arts and Artistic Professions in Segovia (Escuela de Artes Aplicadas y Oficios Artísticon de Segovia) opened a specialisation in “painting techniques and procedures”, in which the sgraffito technique is an essential part of the curriculum [

40]. The academy not only trains staff in the restoration of historic sgraffito but also encourages students to undertake their own creative projects.

A new and unusual application of sgraffito was demonstrated by the master of this technique, Julio Barbero, at the 3rd International Congress of Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism: Timeless Architecture 2022. The artist demonstrated a QR code made in the sgraffito technique, which can be placed on façades, combining tradition and modernity to tell the story of a building or city. During the demonstration, participants could hear after scanning the code with their phones: “Hello friends. I am a Segovian sgraffito of the latest generation. I am a work that combines Segovia’s traditional past with the technological present, and because of the natural durability of this type of plaster, it will still be there for new generations to enjoy in over 100 years’ time. I am sure that when I am an old man, I will be protected by my heritage as a unique element of our façades” [

41].

Sgraffito has been a part of Segovia’s architectural culture for centuries and has become an authentic part of the city’s identity, meeting the criteria for unique cultural heritage. This method of decorating buildings with such an intense variety of patterns can only be found in Segovia. Its original form and numerous applications on the façades of many buildings in the city centre make it a striking feature of the city and undoubtedly its distinctive mark. Furthermore, thanks to the efforts of the city authorities, educational initiatives for young people and the work of masters of this craft, sgraffito will continue to shape the city’s architectural landscape for generations to come.

3.3. Porto—The Magic of Historic Windows

Porto is a city with a long history dating back to the 5th century, as well as a long tradition of construction. The urban fabric of the historic centre and its many historic buildings bear remarkable testimony to the city’s development over the last thousand years. While the area contains many valuable religious and public buildings, it is the unique townhouses with their heavily glazed façades that truly define Porto’s urban landscape. The windows of the historic city centre feature intricate woodwork and occupy most of the façade area of typical residential buildings, making Porto’s residential architecture distinctively beautiful (

Figure 12).

Thanks to the extensive glazing and the façades’ unique window joinery, the series of buildings lining the streets and squares appears as though it has been cut out of the external walls. The glazing reflects light beautifully, creating an impression of lightness, which is emphasised by the lack of architectural decoration. It is this highly original window joinery that gives Porto’s townhouse façades their unique character, and their abundance creates a distinctive townscape. Façades filled with windows featuring intricate divisions or divided by a dense grid of small sections appear light and airy, creating the impression of “lace paintings” for the viewer. Convex muntins and sculptural, decorative transom bars create a sense of chiaroscuro on the façades. This is complemented by the metalwork of the balcony balustrades and the infill of the areas beneath the windows (

Figure 13).

Traditional residential buildings in the city have always been characterised by modest façade solutions and a lack of lavish decoration. The layout of the façades has changed little over the centuries, adhering to a well-established typological matrix [

25].

The modest façades of the 17th-century houses were enhanced in the following century with more varied window joinery, with curved lines towards the end of the century. Relatively small buildings with 3-axis façades account for 78% of the total number of dwellings [

26].

Different types of windows were used, such assliding windows, double-leaf windows or French windows. The windows were divided into small- or medium-sized quarters by straight or arched muntins. The mostly decorated part was upper sash separated by a richly ornamented transom bar. Transom was usually in the shape of a semi-circle or its part or a rectangle. There were also transoms closed with a sharp arch. Fields of transom were divided with muntin bars in the shape of parts of arches running from the middle upward to the sides creating three panes; sometimes, a spacer in the form of a full arch was added. There are also wing divisions into small rectangular quarters. Rails and cover strips were enriched with carving decoration featuring different decoration motives. The most frequent images included acanthus leaves referring to antique ornaments, kimations, tooth or pearl ornaments. Furthermore, various plant motifs were introduced, including twisted spiral columns, rosettes and interwoven lines reminiscent of Manueline decorations, as well as fans and many other forms (

Figure 14).

The introduction of balconies in numerous buildings led to a change. The most common form of window was the French window. These were preceded by decorative openwork balustrades. The double-leaf French window was horizontally divided with muntin into 2, 3 or 4 stripes of double quarters, or they were glazed with so-called, big glass. Under the glazing, at the bottom, there were full wooden panels, either smooth or decorated with carvings of plant motifs placed in medallions (

Figure 15).

Although the historic centre of Porto was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1996 and declared a National Monument in 2001, and despite protective instruments such as the 2006 Resolution of the Council of Ministers, the 2008 Regulatory Code of the Porto City Council and the creation of special municipal bodies, the process of revitalisation of rental houses was very slow. The reason for this was the freezing of rents under the 1950 law [

25]. It was only with the adoption of the new Rent Act in 2012—a law that allowed rents to be raised and leases to be terminated—that investor and property owner interest increased. Numerous renovation projects began, as confirmed by Porto Vivo’s 2013 figures [

42].

A large proportion of the buildings in the historic centre are in private hands. Others are owned by the state, the city and various organisations, including Porto Vivo SRU (Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana da Baixa Portuense, S.A.). The World Heritage Management Plan for Porto’s historic centre includes a study of the state of preservation, the creation and implementation of a revitalisation action plan and a programme to monitor it, for which a special SRU has been set up: Sociedade de Reabilitação Urbana da Baixa Portuense, S.A. The work also included a new city brand [

6].

The result of the above activities—the legislation, the regeneration plan and the efforts of the local authorities and community—is a beautiful historic centre, rich in buildings of significant historical and cultural value. It is noteworthy and commendable that the original window frames have been preserved or replaced with identical copies and that improvements have been made to thermal efficiency without compromising the harmony and stylistic qualities of the front façades. As shown in

Figure 16, this allows for the preservation of building traditions and distinctive elements of residential architecture, thus safeguarding the city’s cultural heritage and unique landscape. However, maintaining the area’s unique, universal value in the long term will require planned and thoughtful management, as well as increased public participation. Although historic windows are an important feature of historic buildings, they are often underestimated in residential architecture. A very large proportion of historic window joinery is deteriorating and is frequently replaced with mass-produced windows made from other materials. Porto is an example of a city where attention to detail, such as historic windows, has resulted in a beautiful and unique cityscape. The revitalisation process here has been a long one and is not yet complete, but the effects are already visible in many of the oldest neighbourhoods.

3.4. Binz—Wooden Verandas and Fretworks

Like most seaside resorts, Binz does not have a long history. Until the middle of the 19th century, it had been a small village with just 149 inhabitants. In the second half of the 19th century, with the development of tourism and the fashion for trips to the bathing resorts, summer visitors began to flock to Binz. Consequently, the village cottages were extended by enlarging attics and adding wooden verandas and porches. In 1876, the first hotel was built, followed by new buildings along the Strandpromenade, which runs alongside the beach. The first hotel right on the beach—the Strandhotel—was built in 1880 by Wilhelm Klünder. The greatest building boom occurred between 1890 and 1910 [

43].

The villas and guesthouses built at the time, with rooms for summer visitors, were given the fashionable forms of resort architecture. Due to the growing popularity of outdoor recreation and its importance for the health, the façades of the buildings featured rows of wooden verandas, loggias and balconies, which were a characteristic feature of holiday resort architecture. Most of the buildings in Binz had a simple body, enriched beyond the verticals of the verandas with avant-corpses, bay windows, attics and turrets, which gave them a lightness and a specific character [

27].

Today, Binz is the largest seaside resort city on the island of Rügen. It is a well-preserved example of a “white town”, with lots of wooden architectural details and decoration, giving the whole place its individual, unique character [

28] (

Figure 17 and

Figure 18a,b).

Made of wood, the balconies, loggias, verandas, gables, half-timbered constructions of the upper parts of buildings or whole storeys, combined with various architectural elements, referring to different stylistic formations, create a perfect conglomerate of forms that match each other and the surrounding nature despite their great diversity. With similar building dimensions, the use of wood and woodcarving decoration and the unification of the buildings through the use of white, which dominates the façades, it makes the street frontages look harmonious. The timber fretwork ornaments give them an unreality that allows a break from reality and encourages relaxation. Together with a few accents in the form of a few villas of various designs and the spa house, the entire resort development creates a unique townscape, which is further emphasised by the blue of the sea along which the main promenade extends (

Figure 19 and

Figure 20).

After the Second World War, refugees from towns that had been destroyed came to Binz, which did not suffer from warfare. The buildings were adapted for year-round use and the originally open verandas were built over. In 1953, Binz, which was on the territory of the former DDR, was hit by the “Aktion Rose”. Hotels and guesthouses in the seaside resorts along the Baltic coast, especially on the island of Rügen, were nationalised, and over than 400 people were imprisoned for alleged offences against the “Protection of Public Property and Other Social Property Act” (VESchG) [

44].

The reunification of Germany in 1990 opened up new opportunities. Many nationalised villas and pensions were returned to their former owners. In the following years, buildings and public spaces were renovated, including the opening of a new pier in 1994. Further work to clean up and enrich the infrastructure of Binz was carried out after 2000, including the opening of the spa park [

45]. A splendidly fitting modern touch is the Rescue Tower, one of the 50 shell structures created by Ulrich Müther. This oval white “tower” with its panoramic windows contrasts perfectly with the greenery and traditional architecture of the resort. The tower serves various functions, including housing the Binz registry office and a small concert hall [

46].

Of great importance for the preservation of the cultural heritage of the resort was the “Regulation on the monuments of the Hauptstraße/Strandpromende Putbuser Straße and Bahnhofstraße in the Baltic resort of Binz” issued by the district administrator of K. Kassner and published on 10 June 2002 [

45]. The ordinance concerned the protection of the urban layout and the appearance of structures and constructions in the said area, which is a historic part of the locality. It emphasised the need to preserve as much of the original historical substance as possible, to preserve the urban layout, the layout of the courtyards-gardens and buildings as well as the silhouettes of the buildings and their dimensions. The document emphasises that “the alignment of historic buildings, together with natural conditions, leads to spatial forms that are interrelated in ways that can be experienced through visual relationships. The sea has a particular influence on the shaping of space”. Importantly, the regulation enshrines the protection not only of the urban layout of streets and squares but also of the traditional structure of the plot with its development. The importance of the architectural, structural and decorative elements of the historic buildings, which are representative of Binz’s architectural heritage, is also emphasised. The silhouette of the locality visible from the water and from the pier was also protected. With the entry into force of the aforementioned ordinance, the listed historic area became subject to the provisions of the Historic Preservation Act, which entailed the control of any work carried out in the historic centre.

The ordinance has had a huge impact on preserving the coherence and uniqueness of the cityscape, which would otherwise have been destroyed by multi-storey hotels. These hotels would have not only destroyed the cultural architectural heritage but also the entire surrounding area. Today, the town impresses with its beautifully restored and harmonised buildings, featuring openwork panels with fretwork decoration that blend beautifully with the coastal landscape. Early 20th-century architects designed the loggias and verandas of Binz’s pensions and hotels to extend the rooms and provide a link to the surrounding nature. While relaxing on a deckchair, visitors could enjoy the fresh air. They were also the equivalent of theatre lodges, where the stage was the promenade with a “performance” played by strolling holidaymakers against a backdrop of sea and dune vegetation as “theatrical decoration”. On the other hand, the buildings, viewed from the beach, pier or sea, were the calling card of the resort and were meant to catch the eye of potential visitors. In addition, it is this unique landscape of Binz that has been preserved, a tangible and intangible heritage at the same time. Despite the great variety of forms, enriched by rows of verandas, loggias or balconies, the houses still look very coherent and harmonious, retaining their individual charm.

4. Results

The analysis of the case studies demonstrated the validity of the research hypotheses. The traditional, unique and well-preserved residential architecture that fills the streets and squares of cities contributes to the urban landscape and its specific genius loci. Despite the separate building traditions, different forms of decoration and architectural elements used and the different sizes, functions and histories of the surveyed centres, the compact and harmonious street frontages filled with townhouses or guest houses, as in Binz, give the towns their unique character. At the same time, the variety of patterns, colours and other details in a given place ensures that the architecture is interesting and that each townhouse or tenement building stands out from its neighbours. Consequently, the overall impression is one of uniformity, with diversity evident on closer inspection.

The comparative morphological method was used to analyse the results, and a classification and typology of the factors influencing the creation of the urban landscapes of the cities described in the case studies was produced. The research findings were summarised according to the studied criteria, which are benchmarked below. These included the following:

Historical analysis;

The most important activities in the field of preservation of housing historic substance;

The most important reasons that led to the success of revitalisation activities in all analysed centres;

Factors influencing the cityscape;

Analysis of activities in the field of revitalisation;

Analysis of specific actions affecting revitalisation processes.

Tables or diagrams were used to summarise the results, with a synthetic presentation of the problem preceding them.

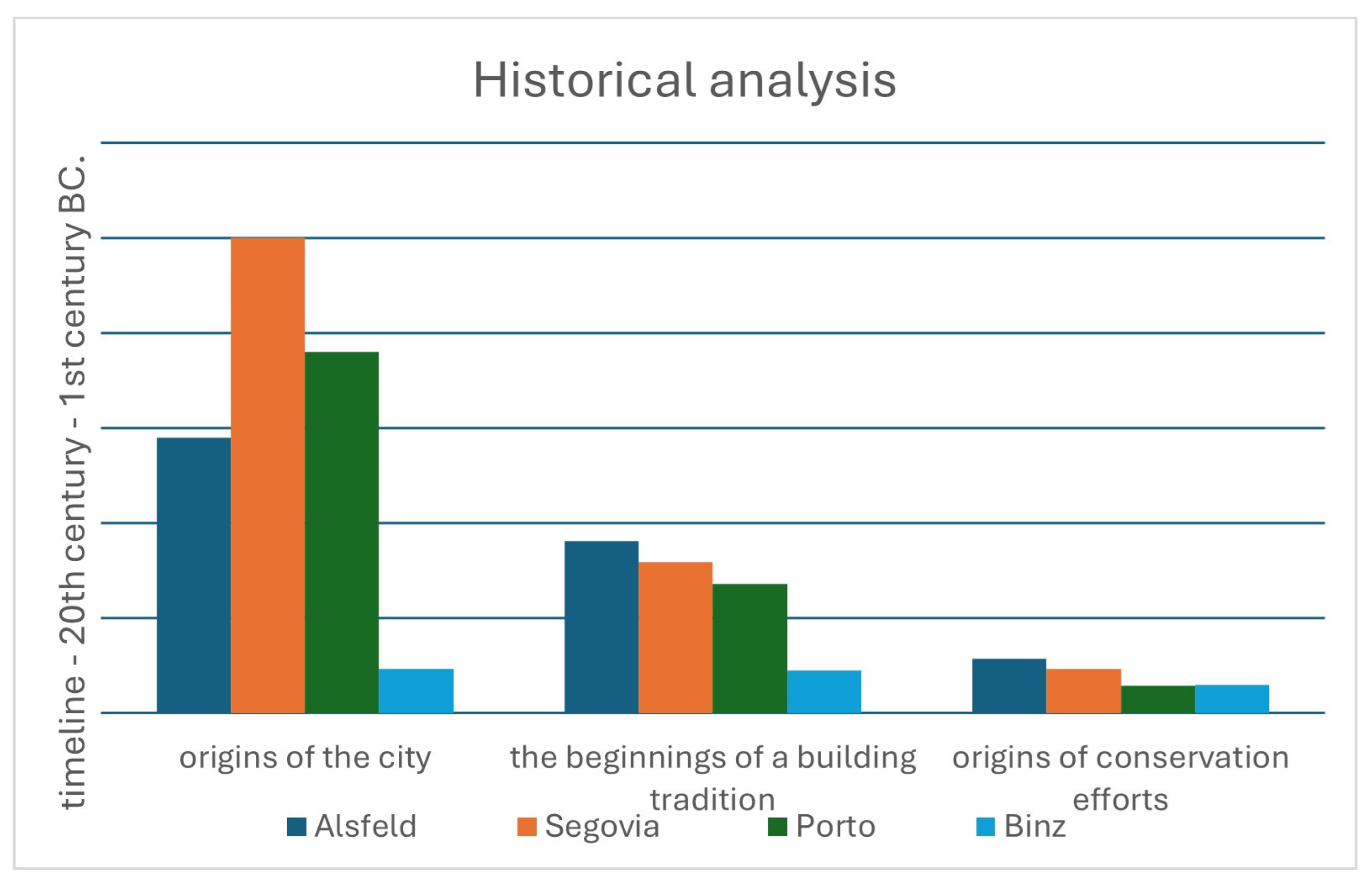

Each of the case studies included a brief analysis of the selected centres’ histories, demonstrating their diversity in terms of the towns’ origins, the beginnings of their traditional residential architecture and their interest in historic preservation and unique local architectural features. The chart below shows these data juxtaposed on a timeline (

Figure 21).

The study showed that the residential architecture of cities with a very long history, such as Segovia, and those that have existed for just over 100 years, such as Binz, can influence a city’s identity, landscape and sustainability.

The townhouses have been kept in good condition thanks to the residents’ respect for architectural monuments and their commitment to conservation measures. Of the centres surveyed, Alsfeld has the longest tradition of historic preservation, with work in this field having been ongoing for over 200 years. This long period of action and learning from mistakes means that the city has amassed the most experience in this field, leading to excellent results. The history of Alsfeld’s revitalisation can serve as an example to other cities, showing both positive actions and mistakes that can be avoided. However, Binz’s recent revitalisation shows that it is possible to recreate a resort’s unique architectural character despite significant destruction. Examples of the most important historic preservation measures in the surveyed centres are shown in

Table 1.

The analysis of studies on selected cities showed how important it is to identify the characteristics of cityscapes in the search for place identity and to act consistently in the field of their authentication, conservation and visual enhancement against the backdrop of urban architecture. In each of the cities in the residential building group, other factors accounted for their uniqueness. The most important characteristics of each centre’s identifiers are summarised in

Table 2.

On the basis of the contextual analysis of the selected urban centres, it was shown that there is a relationship between the care for the tangible architectural cultural heritage in the form of traditional local residential architecture and the intangible heritage in the form of the cultivation of skills and professions associated with traditional architecture. Revitalisations of timber-framed buildings, featuring sgraffito or laubzeg decoration, were carried out by masters in their crafts. Unfortunately, it is only in Segovia that training of young students in the art of sgraffito takes place.

The nomothetic analysis identified the most significant factors contributing to the success of revitalisation activities in all analysed centres:

Although local authorities and organisations were actively involved in all centres, these activities were not always fully thought through. Alsfeld is the best example, having created a broad-spectrum urban development concept after years of experience. Binz is another good example, where sound legal solutions have prevented the destruction of the resort’s character and guided its development. National regulations are also of great importance. The best example here is Porto, where the process of revitalising tenements only began after the law prohibiting landlords from raising rents and evicting non-paying tenants was abolished.

The activities of municipal authorities and local organisations to promote the cities are also important, and these were carried out in all the centres surveyed. These mainly comprise information on architectural heritage, including films, interactive city plans and suggestions for guided tours, such as those in Alsfeld. For example, an interesting idea for the promotion of sgraffito in Segovia, with the inclusion of new technologies, is the production of a barcode in this technique to be placed on buildings, which, when scanned with a phone, conveys information about the building. The local authorities in Porto have paid a lot of attention to creating the city’s brand and helping to promote it. A summary of various examples of activities in the field of regeneration is shown in

Table 3.

Another key point is that specific activities also influence the revitalisation process. It has been demonstrated that the diverse requirements of different cities generate various factors that influence the revitalisation process. Therefore, it is crucial to consider the individual conditions, needs and constraints of each city undergoing revitalisation.

Table 4 shows examples of specific activities carried out in the centres studied.

5. Discussion

Comparative research has shown that, despite the variety of activities undertaken in education, urban and regional policy and public participation, these activities have been carried out extensively everywhere and have covered different areas of life. The experiences of the studied centres, which demonstrate various approaches to revitalisation processes, suggest that superficial actions, such as the mere renovation of building façades, are ineffective in the long term. The research has shown that only balanced actions in cultural, social, economic and architectural-urban fields, preceded by thorough interdisciplinary research and public consultation, can produce good, lasting effects that serve the city and its community for many generations. The importance of involving members of the local community, who must be aware of and accept the measures taken, has also been demonstrated. This is particularly important when revitalising residential buildings, which are usually privately owned. Additionally, public education is crucial, providing guidance on adapting tenement houses and flats to modern standards while preserving historic values, offering favourable financial solutions and ensuring comprehensive project planning within the entire historic area.

Similar conclusions were already drawn and formulated earlier in the form of the 2011 UNESCO General Conference Recommendations on Historic Urban Landscapes (36 C/Resolution 41). The UNESCO recommends that Member States work holistically to integrate policies and practices to protect the built environment with broader urban development objectives, respecting the inherited values and traditions of different cultural contexts.

The case studies also highlight a lack of education for young people in traditional building crafts. Only in Segovia are new cadres being educated for restoration work and artistic work on sgraffito. The problem of education in the traditional building arts is also not a problem of recent years. On 1 December 1987, the Convention for the Protection of the Architectural Heritage of Europe (ETS No. 121) came into force—the so-called Granada Convention—which obliged the countries acceding to it to introduce an integrated conservation policy and to use and develop traditional building techniques and materials.

According to data published in “Urban Heritage for Resilience: Consolidated Results of the Implementation of the 2011 Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape”, artisans familiar with traditional building methods remain an important part of urban development and material heritage protection strategies. There is also a clear need for training to document and protect heritage resources. Of the 125 cities that reported, only three had an updated inventory of their heritage, 51% of which is listed as World Heritage.

The example of Porto shows that integrated actions based on the universal principles of the Granada Convention or the Unesco recommendations can be ineffective if they are not supported by a thorough analysis of the local situation. Most of the countries participating in the consultations on the implementation of Unesco’s objectives reported the problem of coordinating national and local action in the area of heritage conservation in line with the sustainable development agenda, which shows how important it is to take into account the local conditions and needs of towns and cities and to carry out local research and consultations with local people. It also indicates the necessity of conducting studies comparing the mechanisms of revitalisation and heritage protection in different cities and popularising good models. The creation of general methods for revitalisation and indicators for measuring the identity of a place, as described, among others, by Paulina Dudzik-Deko and Joanna Rzeźnik [

3], is needed but is no substitute for reliable in situ research.

There are numerous examples of the revitalisation of historic areas, and many scientific articles have been written on the subject. Usually, they concern one or two centres [

10,

11,

12]. However, the topic’s specificity requires ongoing research, showcasing various examples and facilitating discussions, as most researchers agree. This greatly broadens the spectrum of measures and ideas that can be adapted to individual cases and used as proven models. As the research on the implementation of UNESCO recommendations and the Granada Convention shows, there is an enormous need in this field.

An important limitation of the above studies and of attempts to make generalisations on a larger scale is that each historic city is unique and requires an individual approach, as it is a kind of “living organism”. While piecemeal research is important for raising awareness of urban regeneration issues, it will never capture the full picture and will not allow for far-reaching generalisations. Very broad studies, on the other hand, limit the ability to collect and compare data.

The study was limited to four selected centres, which significantly restricted its scope. Nevertheless, this fragmented research enables comparisons to be made, highlights the importance of the topic and may contribute to ongoing or future revitalisation processes. The authors attempted to select case studies that would widen the scope of the unique characteristics of cities and individual revitalisation activities.

In the context of research by various researchers, it is also important to emphasise the architectural qualities of residential buildings, which are most often overlooked or treated marginally in research. A city’s identity should be based on the unique character of its local culture, and residential buildings not only constitute architectural heritage but also testify to a place’s material culture and its inhabitants. Further comparative research in this area is therefore needed, culminating in a publication that summarises the subject and is based on a much larger number of examples from different continents.

6. Conclusions

Research has shown that historic residential architecture is of great value, and together with the urban layout, it is an important element of architectural cultural heritage. The façades of townhouses stretching along the streets of towns and localities form an urban landscape of great historical and monumental value through their peculiar features. Following an analysis of the current UNESCO heritage protection policy, the conclusion has emerged that the value of historic residential architecture receives little attention as a valuable legacy and part of protecting the identity of a place. The voices of residents and owners of tenement houses are becoming an increasingly important part of the revitalisation process. However, attention is still mostly focused on individual buildings and their surroundings, rather than on compact developments with their own unified aesthetic and historical character. Therefore, it is worth protecting places where this type of architectural heritage has not been affected by incongruous and disfiguring additions to buildings. New buildings should be designed in a way that incorporates traditional elements transformed into the language of contemporary architecture alongside contemporary forms. Only then can the harmony of the urban landscape and the spirit of the place be preserved. Despite the distinctiveness of the traditions and cultural values of cities in different regions, certain general principles of monument protection emerge. These principles were also demonstrated by the research carried out.

Programmes for the revitalisation of historic areas, which are mostly made up of residential buildings, should consist of the following:

Large-scale, interdisciplinary activities, often going beyond the protection of historic buildings alone;

Communication, economic and other solutions to the needs of the local community;

Broad public consultation, encouraging residents to take action;

Acceptance by the local community and stakeholders;

Promotion of a willingness to act and a sense of pride in their local area;

Provision of good access to information about the programme and the opportunities it offers;

Inclusion of favourable financing conditions for private property owners;

Clear and concise terms for the conservation and regeneration project.

The policy of the local authorities, in cooperation with organisations for the protection of historical monuments and conservation services, should be consistent and clearly expressed in ordinances and resolutions. It should also be harmonised with the ordinances of regional or state authorities. It is also advisable to consider which existing ordinances or laws promote historic preservation and which should be amended.

Each city or town has its own building traditions and degree of historic architecture preservation, as well as its own opportunities. Therefore, it is not possible to create a universal historic preservation programme. However, based on general principles and good examples, it is easier to develop your own local projects. It is important to remember that awareness of tradition and cultural roots is vital for people, helping them survive in an increasingly virtual, unified modern world. Nevertheless, residential architecture is the closest thing we have. Therefore, it is important to conduct research into its historic value and its potential to create a sense of place and a city or town’s identity and brand. For this reason, it is also useful to identify townscape features within this architectural group.

_Li.png)