Abstract

Glocalization plays a vital role in promoting regionally embedded sustainable development by enabling territories to adapt global economic impulses to local capacities, values, and institutional frameworks. This paper develops a framework for the quantitative assessment of economic glocalization at the regional level, focusing on the European Union. Drawing on the conceptual metaphor of “refraction”, glocalization is interpreted as a transformation of global economic impulses as they pass through and interact with localized socio-economic structures. The authors construct a Glocalization Index System comprising three sub-indices: (1) Index of Generation of Globalization Impulses, (2) Index of Resistance to Globalization Impulses, and (3) Index of Transformation of Globalization Impulses. Each sub-index integrates normalized indicators related to regional creativity—conceptualized through the four “I”s: Institutions, Intelligence, Inspiration, and Infrastructure—as well as trade and investment dynamics. The empirical analysis reveals substantial interregional variation in glocalization capacities, with regions of Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Finland ranking among the most prominent generators and transformers of globalization impulses. Strong correlations are observed between the Resistance and Transformation indices, supporting the hypothesis that medium resistance levels contribute most effectively to transformation processes. By integrating both global (exogenous) and local (endogenous) dimensions, the proposed framework not only addresses a gap in economic literature but also offers a tool for guiding policies aimed at sustainable, adaptive, and innovation-driven regional development.

1. Introduction

Despite the expectations of the early 1990s, globalization has not been able to eliminate the geographical “space of places”, and local characteristics continue to play an important role in shaping the “space of flows”. Therefore, over the past two decades, the neologism “glocalization” has been increasingly used by both theorists and practitioners to describe the current conditions of economic, social, and cultural relations. Semantically, the term “glocalization” is a hybrid of two words: “globalization” and “localization”, and in a broad sense, it refers to the simultaneous manifestation of trends toward both universalization and particularization of modern social, political, and economic systems.

Glocalization plays a crucial role in fostering regional sustainable development by encouraging the integration of exogenous parameters—such as international investment, transnational knowledge flows, global market demands, and supranational environmental standards—with endogenous parameters—including local cultural values, social capital, institutional capacities, innovation potential, and place-based resource management. Through this dual influence, glocalization promotes regionally tailored development strategies that enhance resilience, support sustainable economic diversification, and reinforce the active role of local actors in adapting global trends to regional priorities.

Regardless of its relatively short history of usage, the terms “glocal” and “glocalization” have gained popularity in contemporary academic literature. A brief review of scholarly publications highlights the following fields where these terms are most frequently applied: international marketing [], social geography [], urban studies [], research methodology [], consumer culture [], popular music and musical culture [], education [], social work [], linguistics and translation [], sociology of sport [], cultural studies of hybridization and creolization [], social movements [], art [], religion [], mass communications [], environmental protection [,], criminology [], and others.

One reason for the popularity of glocalization theory is its stark contrast with Rostow’s modernization theory [], which dominated the social sciences for decades and suggested that all civilizations would inevitably follow the stages of progress already passed by Western civilization. The concept of glocalization rejected the assumption that the world would inevitably become more democratic, more capitalist, more consumption-oriented, and so on.

However, it is worth noting that the etymology of the term glocalization is not fully established. According to the Oxford Dictionary of New Words, the concept of glocalization originates from the Japanese principle dochaku-ka (“to do something in one’s own way”), which was initially used in agriculture to emphasize the need to adapt farming technologies to local conditions. At the same time, in Japan itself, the phrase “global localization” is more often associated with Morita, Sony Corporation CEO, who used the expression in corporate advertising and branding strategies during the 1980s and 1990s [].

A search of scientometric databases for the period 1966–1987 conducted by Roudometof [] found 11 instances of potential use of the word “glocal” (only two of which appeared in scholarly journal articles), though none were confirmed upon direct examination of the sources. The absence of examples of the term “glocal” in the literature of the 1980s casts doubt on the hypothesis of its Japanese origin or its emergence in business circles to denote a marketing strategy. Nevertheless, such claims are now considered almost canonical in most discussions of glocalization.

The first reliably documented use of the term “glocal” was recorded in a speech by M. Lange during an exhibition in Bonn, Germany, in May 1990, describing an exhibit by H. Benking titled “The Black Box of Nature: The Rubik’s Cube of Ecology” []. The purpose of the exhibit was to demonstrate the need to establish connections between the micro-, meso-, and macro-levels of ecological research and initiatives—this multilayered structure was precisely what was characterized by the adjective “glocal”.

However, it was Robertson who introduced the neologism glocalization into wider circulation (in his work “Glocalization: Time-Space and Homogeneity-Heterogeneity”) and applied it in the discourse of the social sciences as a tool for reconciling the global and local dimensions [].

In recent decades, the conceptual rationale of glocalization has evolved significantly, including in economy-related fields. However, attempts at its systematic measurement remain limited. In this research, we propose a systematic approach to the ontology of economic glocalization and its quantitative measurement.

The current paper adds to the state-of-the-art by (i) introducing a multidimensional Glocalization Index System, (ii) adapting the 4I creativity framework into an economic measurement model, and (iii) demonstrating the empirical feasibility of quantifying glocalization at the regional scale. Unlike prior descriptive works, our framework operationalizes glocalization with composite indices, offering policymakers a replicable tool for comparative regional analysis.

2. Literary Review and Ontological Background

2.1. Theoretical Origins of Glocalization

The local-global problematic is well highlighted among researchers. According to Castells’ idea of the “network society” [], there is sharp opposition between the global “space of flows” and the local “space of places.” The “space of flows” represents the communities that are connected through information and computer technologies and do not require physical co-presence. They transform the urban context of the globe. The “space of flows” coexists with the “space of places”—geographic locations that are condensations of history, culture, etc. However, the “space of flows” does not displace traditional geographic space but rather alters its functional and social dynamics.

In Robertson’s understanding, glocalization should serve as a kind of linking element between the “space of flows” and the “space of places” of globalization, denominating the latter geographic dimension [,,]. As Khondker argues, in this interpretation, glocalization is essentially a conceptually advanced version of globalization []. A similar position is shared by proponents of Turner’s ideas of the “enclave society” [], which suggest that globalization implies not only the emergence of new models or actors of integration but also the systematic fragmentation of existing units and the formation of new actors and their associations, capable of communicating and maintaining mobility while circumventing newly created barriers. Thus, globalization does not lead to a new singularity, but instead generates multiple fragmentations, which constitutes glocalization [].

Thus, Robertson’s approach, which can be titled “globalization as glocalization,” offers a central metatheoretical interpretation of the concept of “glocalization” through the postulates of monism—the idea that different types of substances (in this case, the “local” and the “glocal”) ultimately reduce to a single source (in this case, the “global”). According to the researcher, the “global” determines the “local” and is a specific form of its manifestation, while the “local” cannot exist in a pure form outside of the “global”. Consequently, globalization causes the particularization of universalism and the universalization of particularism.

However, Radhakrishnan [] noted that Robertson’s approach is valid only if the time dimension is infinite (i.e., t = ∞, where t is time) or absent, whereas in the short-term or mesotemporal dimension of transformations from t1 to t2, the ideas of monism cannot be fully applied. In other words, there is no answer to the question: how does the relationship between the “global” and the “local” change within temporal intervals?

Critics have also pointed out that Robertson’s inference does not allow for effective representation of centers of influence (i.e., units of power), whose effects become clearly noticeable in a temporal perspective. The “local” is usually seen as a prerogative of communal or social factors, while the “global” is a determinant of corporate or transnational capitalism [,]. Far-right and far-left political forces often view local-global binary relations not as complementary but rather as exploitative and resistant.

Ritzer proposed an alternative approach to the interpretation of glocalization [], which significantly differs from Robertson’s view of the simultaneous manifestation of homogeneity and heterogeneity in globalization processes. Ritzer’s approach may be described as “glocalization as globalization”. Its core tenet is that glocalization is one of two manifestations of globalization, revealing the aspect of social heterogeneity. To describe the other aspect –reflecting the tendency toward homogeneity—Ritzer introduces the term “grobalization,” a hybrid of “to grow” and “globalization”. Thus, grobalization emphasizes rather imperialistic ambitions of some states, corporations, organizations, and so forth, and their attempts to impose their activities on specific geographic territories.

Using programming terminology, Robertson’s approach to the definition of glocalization serves as an example of logical conjunction (operator AND or ∧, which returns ‘true’ only if all operands are ‘true’), whereas Ritzer’s approach employs the principle of exclusive disjunction (operator XOR or ⊕, which returns ‘true’ only when exclusively one operand is ‘true’), which can be illustrated using Formulas (1) and (2).

Robertson’s approach

Globalization ≡ Glocalization ∋ heterogenei ∧ heterogeneity

Ritzer’s approach (early)

Globalization ≡ Glocalization (heterogenity) ⊕ Grobalization (homogenity)

A defining innovative element of Ritzer’s approach is the introduction of the concept of “nothing” (and accordingly “something”) into the methodological framework. “Nothing” is defined as “… as a social form that is generally centrally conceived, controlled, and comparatively devoid of distinctive substantive content” [], p. 195. Ontologically, “nothing” includes elements such as “nonplace,” “nonthing”, “nonperson”, and “nonservice”, which, together with their alternatives (i.e., “place”, “thing”, “person,” and “service”), belong to the subtypes of the general continuum of “something”/“nothing”. Under the conditions of grobalization, “nothing” manifests in phenomena known by vivid labels such as Westernization, Americanization, McDonaldization, Disneyization, Coca-Colonization, and so forth. However, “nothing” can also be expressed within the framework of glocalization—for instance, the rebranding of “Coca-Cola” to suit Asian or Arab markets, or traditional Slavic embroidered shirts labeled “Made in China.” “Something” is typically associated with the context of glocalization—e.g., the services of a local tailor or handmade crafts—but increasingly, its grobalized forms are also emerging. These include the products of companies specializing in gourmet food, worldwide tours by music bands, and youth subcultures that originally emerge in opposition to dominant trends but eventually become part of the mainstream.

Thus, unlike Robertson’s monism, Ritzer’s approach can be described as dualism. His basic postulates were more clearly crystallized in a later work []. In Ritzer’s interpretation, a clear aspect of temporality emerges, as social changes are described over time intervals from t1 to t2. Among the limitations of Ritzer’s approach, one can highlight the fact that positioning glocalization as the antithesis of grobalization restricts the potential for the multidisciplinary application of the term “glocalization” [].

2.2. Autonomous Ontology of Glocalization

In addition to the two approaches to interpreting glocalization discussed above, a third can be distinguished, according to which glocalization should be considered an analytically autonomous concept. The idea of analytical autonomy is borrowed from the work of Alexander [], which focuses on aspects of cultural sociology and the sociology of science. Similarly, it is proposed to clearly define the boundaries for the analytical application of glocalization tools compared to related categories (local, global).

To resolve the dilemma of analytical autonomy, Robertson & White proposed using the concept of diffusion to explain the mechanism of glocalization []. These researchers argued that diffusion explains how ideas and practices spread (or do not spread) from one location to another. However, we believe it would be counterproductive to limit the issue of glocalization solely to aspects of international cultural diffusion.

A somewhat alternative visualization is offered by Therborn’s concept of the wave-like nature of globalization’s spread [], which we will examine in more detail. To avoid terminological confusion (the term “waves of globalization” is typically used to describe the three periods of the most intense international integration over the last 150 years), we will use the term “globalization impulses” in a similar sense to ideas of Therborn. The concept of impulse (or wave) is useful for analytical studies of the type “globalization of X,” where X may refer to a specific field, process, or condition, etc. (this is elaborated in []).

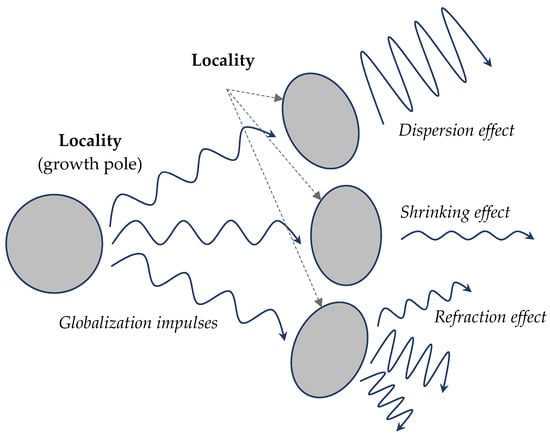

Roudometof updated the conceptual metaphor of diffusion by proposing the use of the metaphor of refraction (in physics, refraction is understood as the bending or dispersion of a light beam, or the change in direction of a radio wave when passing through media with different densities) []. The symbolism of refraction allows for a better reinterpretation of the relationships between globalization and glocalization, specifically:

- (a)

- to view globalization as an all-encompassing process in terms of impulse diffusion in space;

- (b)

- to use the concept of “impulse refraction” as a means of understanding the global-local binary.

By considering the globalization of X from the perspective of refraction, we can speak about the spread of X through locations with different “densities.” In other words, each location must be considered separately, taking into account varying degrees of resistance to globalization impulses. This approach allows us to identify two possible outcomes of the globalization process. First, the impulse-like properties may be amplified or absorbed by the local, and then reappear on the global stage (we propose to call these scenarios the “dispersion effect” and the “shrinking effect,” respectively). This reflection phenomenon is quite accurately described within the conceptual framework of world society theory—largely, this is the mechanism through which institutional isomorphism arises. Second, the impulse may pass through the local environment and be refracted by it (the “refraction effect”). This scenario defines the focus of the proposed study, as from this perspective, glocalization is globalization refracted through the local environment. This approach constitutes a third interpretation of glocalization, establishing its analytical autonomy from globalization processes. The local is neither annihilated, absorbed, nor destroyed by globalization; rather, operating in symbiosis with the global, it shapes the “telos,” i.e., the final state or outcome.

Overall, in this study, we will adhere to the methodological approach proposed by Roudometof in interpreting glocalization []. Viewing glocalization processes through the metaphorical lens of refraction allows for the theoretical substantiation of mesotemporal changes (from t1 to t2) without necessarily assuming total integration as the final outcome (for example, the same “telos” in which the local is completely dissolved). The local can alter the final result; therefore, resistance to grobalization is not a theoretically insignificant category.

In particular, given the specifics of this study, we highlight three main “vectors” of the manifestation of global and local influence:

- The ability of the local to consistently and stably “initiate an impulse” on the global stage, as well as the potential of a particular center of economic, political, and cultural influence to play critically important roles in shaping the configuration of participants. In fact, Beck described such a scenario as “the local globalizing itself from within” [], but this statement is only valid if one disregards interactions with other locations. On a planetary scale, the West has for many centuries played the role of a historical “anchor of globalization,” but the 21st century has become a temporal platform in which the reconfiguration of the global balance of power increasingly tends toward an intercivilizational character à la Huntington [], with the significantly enhanced roles of Chinese, Arab, and Orthodox civilizations.

- The ability of the local to resist unwanted impulses of globalization (the so-called “density”). On the global stage, extreme examples of such resistance include North Korea, though in most cases we are not dealing with such extreme scenarios. An important aspect of “density”—whether economic, cultural, institutional, or military—is that a locality (including nations, religions, etc.) has the capacity for selective acceptance of global influences.

- The ability of the local to modify and refract the impulses of globalization that pass through it. Glocality leads to the creation and spread of hybridity, cultural pluralism, and ethnic and religious heterogeneity in everyday life. In postcolonial theory and specialized cultural studies, terms such as hybridity, creolization, syncretism, and mestizaje have been used as close analogs to “glocality” (see, for example: [,,]). It is undeniable that this glocal hybridity is arguably the most important and visible consequence of the increasing process of social refraction observed in the 21st century [].

An illustration of the logic of the conceptual metaphor of refraction for the main types of glocalization processes is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual metaphor of refraction for glocalization processes. Source: authors inspired by Roudometof [].

A fourth scenario can be identified in the form of a new economic and cultural phenomenon known as “lobalization” [], which denotes a certain type of “revenge” of the local over the global. Lobalization is understood as a situation in which locally produced goods are marketed in the region as prestigious imported brands (either through mimicry, as in the case of the famous Chinese “Abibas,” or as outright copying). An important aspect of this phenomenon is that “lobal” products begin to circulate on a planetary scale, which can negatively affect not only the original global manufacturer but also local creative sectors.

2.3. Application in Economic Research

Aspects of glocalization are most often explored in sociological or cultural studies, whereas its economic dimension typically remains somewhat “in the shadows.” We can distinguish three main vectors of economic research with a glocalization focus: the geoeconomic mapping of the world (macro level); the study of the spatial organization of economic activity (meso level); and the analysis of MNC strategy (micro level). These potential vectors of academic inquiry within the economic sphere of glocalization are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Economic Aspects of Glocalization Research.

The above conceptual approaches allow us to capture the main views on the interaction within the framework of the global-local binary. Of course, the ontology and theory of glocalization are not yet at the stage of final completion. Researchers have not yet reached a final consensus on the delimitation of ontological fields of terms in the chain “global”–“glocal”–“local”.

This study addresses three research questions: (1) To what extent can European regions generate globalization impulses? (2) How do regions resist external impulses? (3) How do regions transform global impulses into localized outcomes? We hypothesize that regions with medium resistance exhibit the strongest transformative capacities.

3. Materials and Methods

Empirical studies focusing on the processes of economic glocalization in European regions (and countries) remain scarce. This is primarily due to the absence of comprehensive statistical data on interregional trade and capital flows, as well as the underdeveloped state of methodological frameworks for interpreting and analyzing glocalization. In open-access sources, we found only a limited number of analytical studies that examine the economic dimensions of glocalization processes in Europe. Notably, the work by Knödler & Albertshauser [], based on the analysis of firm-level foreign direct investment (FDI) data across 32 regions in Western Germany, stands out. Other scholarly contributions addressing the spatial economic aspects of glocalization are predominantly descriptive rather than quantitative. Among these, the studies of glocalization processes in Croatia [] and Romania [] merit specific attention.

As a logical conclusion of our analysis of glocalization processes, we have developed a system of glocalization indices intended to assess the capacity of a location to generate a “globalization impulse,” to resist it, or to modify it in accordance with the conceptual metaphor of refraction, discussed in Section 2.

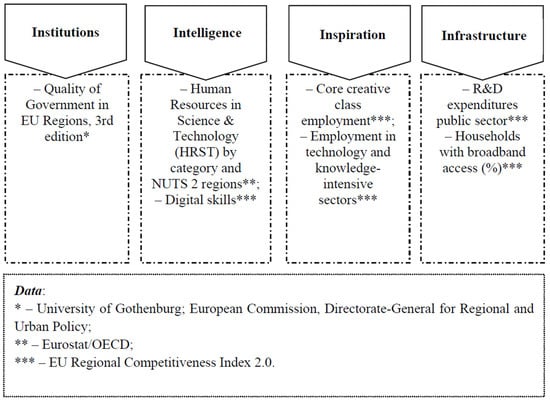

One of the most critical factors shaping a region’s capacity to generate new globalization impulses (primarily through innovation diffusion), to resist such impulses, and to form glocalization systems is the dimension of regional creativity. For analyzing regional creativity, we apply the methodological framework developed by Lishchynskyy & Lyzun [] as adaptation of Sleuwaegen &Boiardi [] approach to identify four “I’s” of regional creativity:

- Institutions

- Intelligence

- Inspiration

- Infrastructure

A methodology for calculation of four parameters of regional creativity is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Methodology of 4-I of regional creativity. Sources: [,].

A crucial aspect of such approach is that proposed parameters of creativity are endogenous to the system, unlike, for instance, firm location choices. Given their endogeneity, these four parameters also serve as important strongholds of the glocalization complex formed within a given territory (in our case, the EU). However, we could not ignore the global forces, such as trade or investment, when assessing the parameters of regional sustainability [].

Variables were selected based on theoretical alignment with the 4I framework [] and data availability across EU regions. For instance, Inspiration and Infrastructure represent proactive creative capacities, hence placed in Generation and Transformation indices. Conversely, Institutions and Intelligence reflect more passive absorptive capacities, thus aligned with Resistance.

In the paper, we propose the Glocalization Index System that comprises three sub-indices:

- 1.

- Index of Globalization Impulses Generation—a composite of normalized (on a 0 to 1 scale) values for the most proactive parameters of regional creativity and indicators of dominance in capital, goods flows, and ownership distribution. The sub-index consists of:

- (a)

- “Inspiration,” measured by the growth of real employment in high-tech sectors relative to baseline conditions characterized by higher education coverage and quality.

- (b)

- “Infrastructure,” reflecting a region’s capacity for rapid innovation diffusion.

- (c)

- Total patent applications (European Commission, 2022, Regional Competitiveness Report).

- (d)

- Foreign affiliates of the EU enterprises (Eurostat indicator “fats_out_activ”) according to the net turnover.

- (e)

- Outward Foreign Direct Investment according to OECD Benchmark Definition BMD4, percentage of GDP (OECD data).

- (f)

- Sales of new-to-market and new-to-firms innovation (European Commission, 2022, Regional Competitiveness Report).

- 2.

- Index of Resistance to Globalization Impulses (so-called regional “density”)—a composite of more passive creativity parameters (“Institutions” and “Intelligence”), government R&D support, and indicators of import substitution or displacement of foreign-controlled firms, goods, and capital. It includes:

- (a)

- “Institutions,” indicating the development of the local and national social environment.

- (b)

- “Intelligence,” describing the population’s potential for innovation perception and critical evaluation of globalized products.

- (c)

- Government R&D expenditures, part of the “Infrastructure” parameter and a proxy for state support of local/national creative identity.

- (d)

- Reverse of foreign controlled EU enterprises by NACE Rev.2 activity and country of control (Eurostat indicator “fats_activ”)

- (e)

- Reverse ratio of inward FDI to regional GDP (OECD).

- (f)

- Reverse ratio of imports of goods and services to regional GDP.

- 3.

- Index of Globalization Impulse Transformation—this captures a region’s ability to modify incoming economic flows and act as their “modifier” or “amplifier.” The structure includes:

- (a)

- “Inspiration” to reflect the broader characteristics of employment in creative and innovation-driven sectors.

- (b)

- “Infrastructure,” essential for evaluating a region’s capacity to receive and disseminate informational (and partially economic) flows, including via air connectivity.

- (c)

- Total patent applications (European Commission, 2022, Regional Competitiveness Report).

- (d)

- Foreign affiliates of the EU enterprises (Eurostat indicator “fats_out_activ”) according to the net turnover.

- (e)

- Reverse indicator of net inward FDI relative to regional GDP (OECD), capturing the magnitude and direction of capital flows.

- (f)

- Net exports-to-GDP ratio, reflecting the direction and intensity of regional goods flows.

Unlike 4I parameters, proposed methodology comprises both endogenous and exogenous parameters of regional sustainability and regional interaction in global space.

All three glocalization sub-indices were calculated as the sum of normalized values of six component indicators for the year 2022. The Glocalization Index System is constructed as a composite indicator, both categorical and continuous variables were included.

To ensure mathematical rigor, each indicator was normalized and polarity-adjusted before aggregation. We use min–max normalization, as recommended in the OECD Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators []. Normalization was calculated according to the equation:

Normalized value = (Indicator value—Minimum value)/

(Maximum value—Minimum value),

(Maximum value—Minimum value),

Sub-indices were aggregated by simple summation of normalized indicators, following Handbook [] (Step 7), which balances interpretability and transparency. Accordingly, the range of permissible index values varied from 0 to 6 (however, the maximum observed value for all three sub-indices in practice was 5.26). A limitation of this calculation methodology is that part of the data is available only at the national level (specifically indicators, “d”, “e” from the list of sub-index components), which leads to slightly inflated index values for peripheral regions of developed countries (and conversely, underestimated values for innovative and creative regions in less developed countries).

4. Results

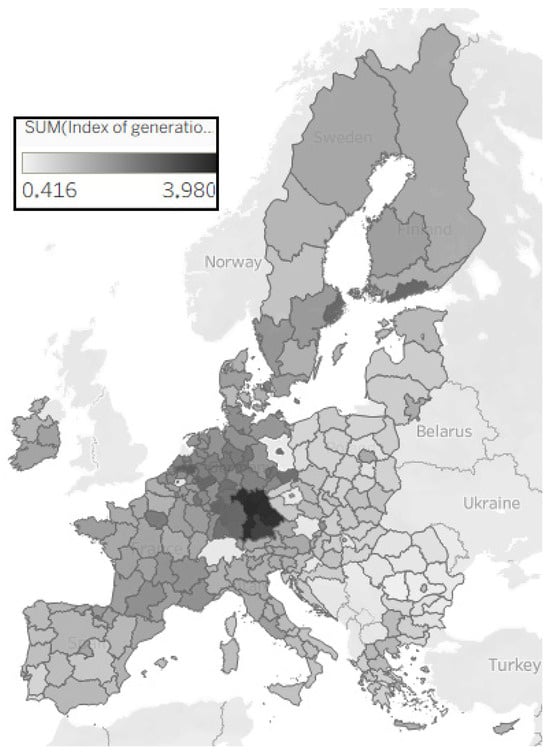

The visualization of the distribution of the Sub-Index of Globalization Impulse Generation is presented in Figure 3. Of the top ten regions with the highest sub-index values, seven are located in Germany (DE: 11, 12, 14, 21, 25, A2, B3), the Netherlands (Noord-Brabant), Sweden (Stockholm), and Finland (Helsinki). Bayern and Upper Bavaria stand out in particular, with sub-index values exceeding 3.4. The lowest values (below 1.0) were recorded in several regions of Bulgaria (BG: 32, 33, 34), Greece (EL: 42) and Romania (RO: 11, 12, 22, 31, 41, 42).

Figure 3.

Sub-Index of Globalization Impulses Generation for EU regions. Source: compiled by the authors using Tableau Desktop 2025.2.

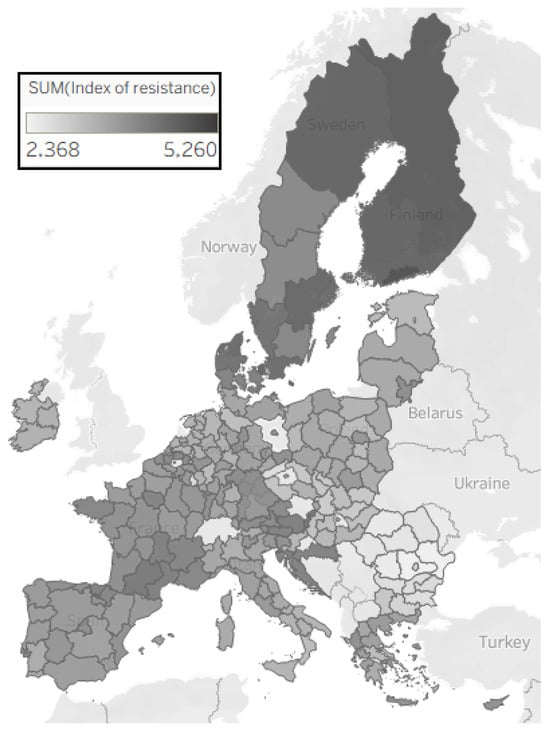

The distribution of EU regions according to the Resistance Sub-Index values is shown in Figure 4. Among the regions demonstrating the greatest “density” to external influences are those of Sweden (SE: 11, 12, 22, 33), Finland (FI: 19, 1B, 1C, 1D), and Denmark (DK: 01, 05). Peak sub-index values (above 5.0) were observed among Finnish regions. The lowest scores (below 2.7) were recorded in regions of Romania (RO: 11, 12, 21, 22, 31, 41, 42), Luxembourg, and Bulgaria (BG: 31, 34).

Figure 4.

Sub-Index of Resistance to Globalization Impulses for the EU regions. Source: compiled by the authors using Tableau Desktop 2025.2.

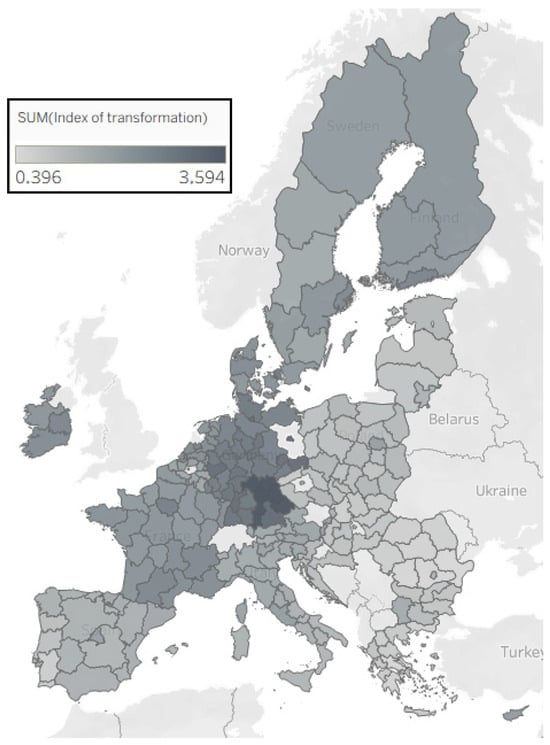

A map of regions according to the Transformation Sub-Index values is shown in Figure 5. All top ten regions are located in Germany (DE: 12, 21, 25, 30, 60, 71, 91, A2, D2, D5), while the lowest positions are occupied by regions of Greece (EL: 42, 51, 62, 64, 65), and Romania (RO: 12, 21, 22, 31, 41).

Figure 5.

Sub-Index of Globalization Impulse Transformation for the EU regions. Source: compiled by the authors using Tableau Desktop 2025.2.

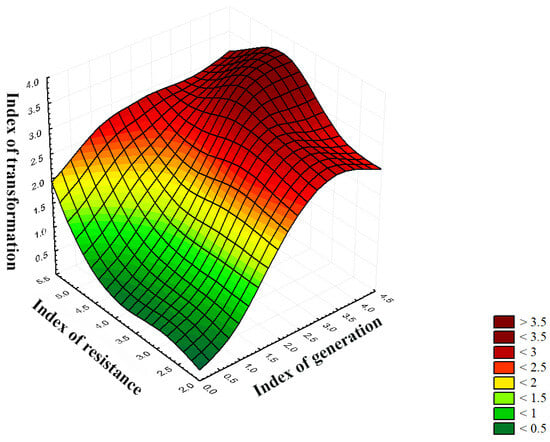

Despite the rather distinct calculation methodology, there is a strong linear correlation between the values of the Generation and Transformation Indices (see Table 2). Although the bivariate correlation between Resistance and Transformation indices is modest (r = 0.393), regression analysis shows a significant positive slope, indicating that moderate levels of resistance still play a facilitative role in transformation. Thus, the observed relationship is non-linear, consistent with our hypothesis.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix (italicized) and regression equations for glocalization sub-indices.

The choice of a linear regression framework for testing the significance of relationships among sub-indices follows its widespread application in composite index validation (see Greco et al., 2019 []). While alternative approaches such as principal component analysis (PCA) or structural equation modeling (SEM) could be applied, regression analysis was selected for its interpretability and suitability to small-sample, cross-sectional data.

Figure 6 presents a 3D chart showing the dependency between the three glocalization sub-indices, where the weighted average distance is adjusted using the least squares method. It is evident that indexes of generation and transformation reach their maximum under the medium values of resistance index.

Figure 6.

A 3D plot of the interrelation between glocalization sub-indices (weighted average distance adjusted by least squares method). Source: compiled by the authors.

The methodology for calculating the index system proposed here is the first attempt at a comprehensive formal assessment of glocalization processes in economic literature. Despite certain limitations (mainly due to the lack of some statistical data at the regional level), the application of this approach allows for both comparative analysis across all regions and temporal dynamics evaluation for specific regions.

Nevertheless, the full spectrum of glocalization processes in a region cannot be adequately captured solely through quantitative instruments and should, in any case, be complemented by a qualitative assessment of the local social context.

5. Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, part of the data is only available at the national level, which may bias regional scores. Second, the cross-sectional design (2022 only) does not capture dynamic evolution. Third, the focus on EU economies with a high share of countries with a single currency limits generalizability to regions with different institutional frameworks. These constraints should be addressed in future research.

While the proposed model demonstrates feasibility in quantifying glocalization, we acknowledge its mathematical limitations. The reliance on linear regression is a first step toward testing significance; future research may incorporate more advanced techniques such as PCA, SEM, or network modeling to refine the robustness of results. Nonetheless, the findings are consistent with our central question: regions with balanced resistance exhibit greater transformative capacity

6. Conclusions

The phenomenon of glocalization has often been discussed in theoretical and cultural terms, but its economic dimension remains underexplored, particularly in terms of measurable, region-specific dynamics. This study offers a structured attempt to fill that gap. Our findings suggest that glocalization is not merely a passive response to globalization, but a dynamic and strategic process rooted in the endogenous capacities of regions. By proposing a new index system composed of three interrelated sub-indices—generation, resistance, and transformation of globalization impulses—we provide a methodological foundation for capturing how local economic systems interact with global forces.

Our findings suggest that glocalization is not merely a passive response to globalization, but a complex process shaped by the internal capacities of regions. The results confirm that creativity—when institutionalized through education, innovation infrastructure, and governance quality—becomes a critical force in driving or reshaping global flows. Regions like Bavaria, Stockholm, and Helsinki exemplify this capacity, acting not only as recipients but also as active filters and amplifiers of global impulses.

Interestingly, we observed that the most successful glocalizers are not necessarily those with the highest resistance to globalization. Instead, regions with moderate levels of resistance often exhibit the greatest adaptability—absorbing global influences and reshaping them in ways that reflect local identity and economic priorities. This challenges conventional assumptions about openness versus protectionism, suggesting that the key to successful glocalization lies in balance, not extremity.

The conceptual metaphor of “refraction”—viewing globalization as an impulse bending through the prism of local context—proved to be more than illustrative. It helped frame a new ontology for understanding the local-global interface in economic terms. While this model is not without limitations, particularly regarding data availability and scale sensitivity, it opens the door for a new generation of comparative regional studies.

Ultimately, glocalization is not a static condition but a dynamic capability. As globalization continues to evolve, so too will the ways in which local economies respond—not by retreating inward, but by redefining how they connect, resist, and transform.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.L., M.L.; methodology, I.L., M.L. and S.B.; software, I.L.; validation, I.L., A.K., O.D. and M.L.; formal analysis, I.L., M.L. and S.B.; investigation, I.L. and M.L.; resources, I.L., A.K., O.D. and M.L.; data curation, I.L., A.K., O.D. and M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, I.L., A.K., O.D., S.B. and M.L.; writing—review and editing, I.L., A.K., O.D. and M.L.; visualization, I.L.; supervision, O.D. and M.L.; project administration, A.K. and M.L.; funding acquisition, A.K., M.L. and S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Experimental studies in this article do not require approval from a Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Grigorescu, A.; Zaif, A. The Concept of Glocalization and Its Incorporation in Global Brands’ Marketing Strategies. Int. J. Bus. Manag. Invention 2017, 6, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Swyngedouw, E. Globalisation or ‘Glocalisation’? Networks, Territories and Rescaling. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2004, 17, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paganoni, M.C. City Branding and Social Inclusion in the Glocal City. Mobilities 2012, 7, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobo, G. Glocalizing Methodology? The Encounter Between Local Methodologies. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2011, 14, 417–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith Maguire, J.; Hu, D. Not a Simple Coffee Shop: Local, Global and Glocal Dimensions of the Consumption of Starbucks in China. Soc. Identities 2013, 19, 670–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, I.; Jang, W. From Globalization to Glocalization: Configuring Korean Pop Culture to Meet Glocal Demands. In Handbook of Culture and Glocalization; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 256–271. [Google Scholar]

- Radjuni, A.J. Glocalization: An Emerging Approach in Teacher Education. Open Access Indones. J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P.Y.P.; Song, I.H. Glocalization of Social Work Practice: Global and Local Responses to Globalization. Int. Soc. Work 2010, 53, 656–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, H.K.; Cheung, L.H. Cultural Identity and Language: A Proposed Framework for Cultural Globalisation and Glocalisation. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 2011, 32, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Waquet, A.; Campillo, P. The Glocalization of Sport: A Research Field for Social Innovation. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, L. Glocal Imaginaries. Postcolonial Text 2011, 6. Available online: https://www.postcolonial.org/index.php/pct/article/view/1323/1169 (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- Urkidi, L. A Glocal Environmental Movement Against Gold Mining: Pascua–Lama in Chile. Ecol. Econ. 2010, 70, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abazine, L. Glocalization: An Analytical Path Towards More Inclusive Contemporary Art? J. Extreme Anthropol. 2017, 1, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dessì, U. Glocalization and the Religious Field. In Handbook of Culture and Glocalization; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dowd, T.J.; Janssen, S. Globalization and Diversity in Cultural Fields: Comparative Perspectives on Television, Music, and Literature. Am. Behav. Sci. 2011, 55, 519–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetman, O.; Iermakova, O.; Laiko, O. Eco-Innovations under Conditions of Glocalization of Economic and Sustainable Development of the Regional Economy. Ekon. Środowisko 2019, 4, 69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stukalo, N.V.; Lytvyn, M.V.; Golovko, L.S.; Kolinets, L.B.; Pylypenko, Y. Ensuring sustainable development in the countries of the world based on environmental marketing. Nauk. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2020, 3, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeres, F. Glocal Policing. In Cross-Border Law Enforcement: Regional Law Enforcement Cooperation–European, Australian and Asia-Pacific Perspectives; Hufnagel, S., Harfield, C., Bronitt, S., Eds.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2012; pp. 109–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow, W.W. The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edgington, D.W.; Hayter, R. “Glocalization” and Regional Headquarters: Japanese Electronics Firms in the ASEAN Region. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2013, 103, 647–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, V. The Glocal and Global Studies. Globalizations 2015, 12, 774–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, C. (Ed.) International Encyclopedia of Systems and Cybernetics; K.G. Saur: Munich, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Glocalization: Time–Space and Homogeneity–Heterogeneity. In Global Modernities; Robertson, R., Featherstone, M., Lash, S., Eds.; Sage: London, UK, 1995; pp. 25–54. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture; Basil Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Globalization: Social Theory and Global Culture; Sage: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Situating Glocalization: A Relatively Autobiographical Intervention. In Global Themes and Local Variations in Organization and Management: Perspectives on Glocalization; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Khondker, H.H. Globalisation to Glocalisation: A Conceptual Exploration. Intellect. Discourse 2005, 13, 181–199. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, B. The Enclave Society: Towards a Sociology of Immobility. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2007, 10, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M.B. It’s About Globalization, After All: Four Framings of Global Studies. A Response to Jan Nederveen Pieterse’s ‘What is Global Studies?’ Globalizations 2013, 10, 771–777. [Google Scholar]

- Radhakrishnan, S. Limiting Theory: Rethinking Approaches to Cultures of Globalization. In The Routledge International Handbook of Globalization Studies; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 44–60. [Google Scholar]

- Korff, R. Local Enclosures of Globalization: The Power of Locality. Dialect. Anthropol. 2003, 27, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, W.H. Mapping the “Glocal” Village: The Political Limits of “Glocalization”. Continuum 2000, 14, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G. Rethinking Globalization: Glocalization/Grobalization and Something/Nothing. Sociol. Theory 2003, 21, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G.; Richer, Z. Still Enamoured of the Glocal: A Comment on ‘From Local to Grobal, and Back’. Bus. Hist. 2012, 54, 798–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roudometof, V. Theorizing Glocalization: Three Interpretations. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2016, 19, 391–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J. The Meanings of Social Life: A Cultural Sociology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R.; White, K.E. What is Globalization? In The Blackwell Companion to Globalization; Ritzer, G., Ed.; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 54–66. [Google Scholar]

- Therborn, G. Globalizations: Dimensions, Historical Waves, Regional Effects, Normative Governance. Int. Sociol. 2000, 15, 151–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrow, M. Global Age. In The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Globalization; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Roudometof, V. Glocalization: A Critical Introduction; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, U. What is Globalization? Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, S.P. The Clash of Civilizations? Foreign Aff. 1993, 72, 22–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canclini, N.G. Hybrid Cultures: Strategies for Entering and Leaving Modernity; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, R. Creolization and Cultural Globalization: The Soft Sounds of Fugitive Power. Globalizations 2007, 4, 369–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraidy, M.M. Hybridity: Or the Cultural Logic of Globalization; Temple University Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nederveen Pieterse, J. Globalization and Culture: Global Mélange; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, M.M. Delineating the Emergent Global Cultural Dynamic of ‘Lobalization’: The Case of Pass-Off Menswear in China. Continuum 2010, 24, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knödler, H.; Albertshauser, U. Glocalisation, Foreign Direct Investment and Regional Development Perspectives: Empirical Results for West German Regions. HWWA Discuss. Pap. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Marošević, K.; Bošnjak, D. Regional Development and Glocalisation: Theoretical Framework. Ekon. Vjesn. Rev. Contemp. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Issues 2018, 31, 201–213. [Google Scholar]

- Pascaru, M. Romanian Glocalization: Case Study on the Rosia Montana Gold Corporation Mining Project. Rev. Cercet. Interv. Soc. 2013, 43, 39–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lishchynskyy, I.; Lyzun, M. Pattern of European Regional Creativity: Exploring Endogenous Sustainability. Econ. Innov. Econ. Res. J. 2024, 12, 397–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleuwaegen, L.; Boiardi, P. Creativity and Regional Innovation: Evidence from EU Regions. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1508–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yankovyi, O.; Kozak, Y.; Lyzun, M.; Lishchynskyy, I.; Savelyev, Y.; Kuryliak, V. Investment Decision Based on Analysis of Mathematical Interrelation between Criteria IRR, MIRR, PI. Financ. Crédit. Act. Probl. Theory Pract. 2022, 5, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Greco, S.; Ishizaka, A.; Tasiou, M.; Torrisi, G. On the Methodological Framework of Composite Indices: A Review of the Issues of Weighting, Aggregation, and Robustness. Soc. Indic. Res. 2019, 141, 61–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).