Emotions for Sustainable Oceans: Implications for Marine Conservation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. How Can Emotions Be Conceptualized to Inform Ocean Sustainability Research and Policy?

2.1. Cognitive-Affective Pathway

2.2. Social Psychological Pathway

2.3. Human Geography Pathway

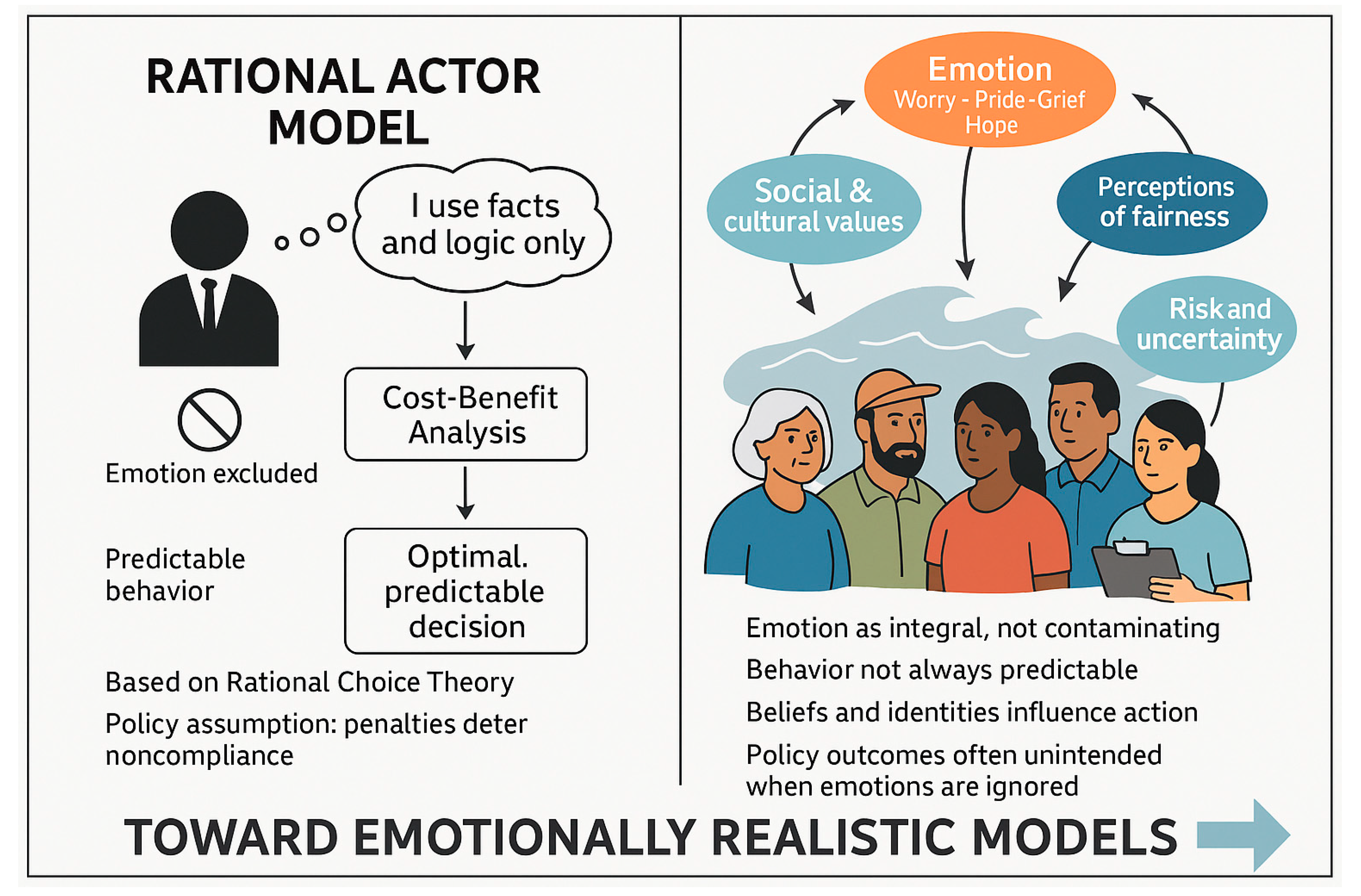

3. What Dominant Ways of Thinking and Alternatives Inform How Emotions Are Understood in Marine Contexts?

3.1. Rationality Bias

3.2. Predictability Bias

3.3. Context-Ignorance Bias

4. How Can Emotion Be Applied to Improve Marine Conservation Research and Practice?

4.1. Recognizing What Emotions Are for Marine Conservation

4.2. The Experience of Emotions Is the Experience of Marine Conservation

4.3. Emotions Influence, and Are Influenced by, the Social and Cultural Aspects of Marine Conservation

5. Conclusions and Next Steps

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Feldman Barrett, L. How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain; Mariner Books: Boston, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, D.D. Neurosociology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, S.E.; Tubi, A. Terror Management Theory and Mortality Awareness: A Missing Link in Climate Response Studies? WIREs Clim. Change 2018, 10, e566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grund, J.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Büssing, A.G. Emotions and Transformative Learning for Sustainability: A Systematic Review. Sustain. Sci. 2024, 19, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, T.; Steg, L. Leveraging Emotion for Sustainable Action. One Earth 2021, 4, 1693–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, E.J.; Wolfe, S.; Nayak, P.K.; Armitage, D. Coastal Fishers’ Livelihood Behaviors and Their Psychosocial Explanations: Implications for Fisheries Governance in a Changing World. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 634484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A. Environmental Models, Cultural Values, and Emotions: Implications for Marine Resource Use in Tonga. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2002, 11, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, P.; Gribble, M.O.; Antelo, M.; Ainsworth, G.B.; Hyder, K.; van den Bosch, M.; Villasante, S. Recreational fishing, health and well-being: Findings from a cross-sectional survey. Ecosyst. People 2022, 18, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, J. Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support in the Relationship Between Emotion Regulation and Quality of Life in Chinese Ocean-Going Fishermen. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espasandín, L.; Coll, M.; Sbragaglia, V. Distributional range shift of a marine fish relates to a geographical gradient of emotions among recreational fishers. Ecol. Soc. 2024, 29, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, J.; Giger, J.-C.; Oliveira, J.; Pacheco, L.; Gonçalves, G.; Silva, A.A.; Costa, I. Psychological Pathways to Ocean Conservation: A Study of Marine Mammal Park Visitors. J. Zool. Bot. Gard. 2024, 5, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pita, C.B.; Horta e Costa, B.; Franco, G.; Coelho, R.; Sousa, I.; Gonçalves, E.J.; Gonçalves, J.M.S.; Erzini, K. Fishers’ Perceptions about a Marine Protected Area over Time. Aquac. Fish. 2020, 5, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R.; Pecl, G.T.; Fleming, A. Social licence in the marine sector: A review of understanding and application. Mar. Policy 2017, 81, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G.; et al. Conservation Social Science: Understanding and Integrating Human Dimensions to Improve Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2017, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, N.J.; Bennett, N.J.; Day, J.C.; Gruby, R.L.; Wilhelm, T.A.; Christie, P. Human Dimensions of Large-Scale Marine Protected Areas: Advancing Research and Practice. Coast. Manag. 2017, 45, 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aswani, S. Perspectives in Coastal Human Ecology (CHE) for Marine Conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2019, 236, 233–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Putten, I.E.; Frusher, S.; Fulton, E.A.; Hobday, A.J.; Jennings, S.M.; Metcalf, S.; Pecl, G.T. Empirical Evidence for Different Cognitive Effects in Explaining the Attribution of Marine Range Shifts to Climate Change. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2016, 73, 1306–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, N.C.; Gurney, G.G.; Marshall, N.A.; Whitney, C.K.; Mills, M.; Gelcich, S.; Bennett, N.J.; Meehan, M.C.; Butler, C.; Ban, S.; et al. Well-Being Outcomes of Marine Protected Areas. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J. Using Perceptions as Evidence to Improve Conservation and Environmental Management. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 582–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, M.; Vaske, J.J.; Bath, A.J. Value Orientations and Beliefs Contribute to the Formation of a Marine Conservation Personal Norm. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 55, 125806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, A.; Clifton, J.; Harvey, E.S. Attitudes to a Marine Protected Area Are Associated with Perceived Social Impacts. Mar. Policy 2018, 94, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuno, A.; Matos, L.; Metcalfe, K.; Godley, B.J.; Broderick, A.C. Perceived Influence over Marine Conservation: Determinants and Implications of Empowerment. Conserv. Lett. 2021, 14, e12790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, A.M.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Jentoft, S. Values, Images, and Principles: What They Represent and How They May Improve Fisheries Governance. Mar. Policy 2013, 40, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiskainen, M.; Sovacool, B.K. Mixed Feelings: A Review and Research Agenda for Emotions in Sustainability Transitions. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2021, 40, 609–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Oceanographic Commission of the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. The United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainability Development (2021–2030): Implementation Plan; Ocean Decade Series 20; International Oceanographic Commission of the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2021; pp. 1–54. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Ocean We Need for the Future We Want: Ocean Science for Sustainable Development [Online]. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/ocean (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Hamilton, L.C.; Butler, M.J. Outport adaptations: Social indicators through Newfoundland’s cod crisis. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 2001, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mather, C. From cod to shellfish and back again? The new resource geography and Newfoundland’s fish economy. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 45, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBC News. Cod Moratorium Marked 20 Years Later. CBC News. 1 July 2012. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/cod-moratorium-marked-20-years-later-1.1261796 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- CBC. This Island That We Cling to [Video]. CBC. 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qSqDFT2z0b8 (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- CBC News. How N.L. Lost Much More Than a Fishing Industry. CBC News. 2012. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M9VYRnB7mdg (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- CBC News Newfoundland and Labrador. Caught in the Middle of the Crab Crisis [Video]. CBC News. 2023. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=szt29RUiWQg (accessed on 14 August 2025).

- Andrews, E. Strategic Outreach for Marine Conservation [Report]; Moving Together for Marine Conservation: St. John’s, NL, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arias Schreiber, M.; Gillette, M.B. Reconceptualizing coastal fisheries conflicts: A Swedish case study. Marit. Stud. 2023, 22, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S. Collective Feelings: Or, the Impressions Left by Others. Theory Cult. Soc. 2004, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hidalgo, M.; Zografos, C. Emotions, Power, and Environmental Conflict: Expanding the ‘Emotional Turn’ in Political Ecology. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2020, 44, 235–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landmann, H. Emotions in the Context of Environmental Protection: Theoretical Considerations Concerning Emotion Types, Eliciting Processes, and Affect Generalization. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 24, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Antonetti, P.; Maklan, S. Feelings That Make a Difference: How Guilt and Pride Convince Consumers of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Consumption Choices. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 124, 117–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzioni, A. Normative-Affective Factors: Toward a New Decision-Making Model. J. Econ. Psychol. 1988, 9, 125–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.D. The Vulcanization of the Human Brain: A Neural Perspective on Interactions Between Cognition and Emotion. J. Econ. Perspect. 2005, 19, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northoff, G. Humans, Brains, and Their Environment: Marriage between Neuroscience and Anthropology? Neuron 2010, 65, 748–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatfield, E.; Rapson, R.L.; Le, Y.L. Emotion Contagion and Empathy. In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; Decety, J., Ickes, W., Eds.; MIT Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman Barrett, L. The Theory of Constructed Emotion: An Active Inference Account of Interoception and Categorization. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2017, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; Côté, S. The Social Effects of Emotions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2022, 73, 629–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isen, A.M. Some Ways in Which Positive Affect Influences Decision Making and Problem Solving. In Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 548–549. [Google Scholar]

- Keltner, D.; Haidt, J. Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion. Cogn. Emot. 2003, 17, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A.H.; Manstead, A.S.R. Social Functions of Emotion. In Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 456–470. [Google Scholar]

- LeDoux, J.E. The Emotional Brain; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Damasio, A. Strange Order of Things: Life, Feeling, and the Making of Cultures; Pantheon: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zadra, J.R.; Clore, G.L. Emotion and Perception: The Role of Affective Information. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 2011, 2, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelissen, R.M.A.; Dijker, A.J.M.; de Vries, N.K. Emotions and Goals: Assessing Relations between Values and Emotions. Cogn. Emot. 2007, 21, 902–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A. The Integrated Theory of Emotional Behavior Follows a Radically Goal-Directed Approach. Psychol. Inq. 2017, 28, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frijda, N.H.; Manstead, A.S.R.; Bem, S. (Eds.) Emotions and Beliefs: How Feelings Influence Thoughts; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, E.; Kangas, M. The Relationship between Beliefs about Emotions and Emotion Regulation. Behav. Change 2021, 39, 205–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennison, J. Emotions: Functions and Significance for Attitudes, Behaviour, and Communication. Migr. Stud. 2024, 12, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; Van den Berg, H. The Persuasive Power of Emotions: Effects of Emotional Expressions on Attitude Formation and Change. J. Appl. Psychol. 2015, 100, 1124–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maia, R.C.M.; Hauber, G. The Emotional Dimensions of Reason-Giving in Deliberative Forums. Policy Sci. 2020, 53, 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thagard, P. Hot Thought: Mechanisms and Applications of Emotional Cognition; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Von Scheve, C.; Salmela, M. Collective Emotions; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thonhauser, G. Towards a Taxonomy of Collective Emotions. Emot. Rev. 2022, 14, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thagard, P.; Kroon, F.W. Emotional Consensus in Group Decision-Making. Mind Soc. 2006, 5, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.R.; Mackie, D.M. Intergroup Emotions. In Handbook of Emotions, 3rd ed.; Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J.M., Barrett, L.F., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 428–439. [Google Scholar]

- Devine-Wright, P.; Whitmarsh, L.; Gatersleben, B.; O’Neill, S.; Hartley, S.; Burningham, K.; Sovacool, B.; Barr, S.; Anable, J. Placing People at the Heart of Climate Action. PLoS Clim. 2022, 1, e0000035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norgaard, K.M. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Leviston, Z.; Hurlstone, M.; Lawrence, C.; Walker, I. Emotions Predict Policy Support: Why It Matters How People Feel about Climate Change. Glob. Environ. Change 2018, 50, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Eco-Anxiety, Tragedy, and Hope: Psychological and Spiritual Dimensions of Climate Change. Zygon 2018, 53, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihkala, P. Toward a Taxonomy of Climate Emotions. Front. Clim. 2022, 3, 738154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queirós, A.M.; Sutherland, W.J.; Boyes, S.J.; Burchard, H.; Calado, H.; Clarke, L.J.; Cripps, G.; Crowder, L.B.; Dallimer, M.; de Juan, S.; et al. The opportunity for climate action through climate-smart marine spatial planning (CSMSP). Nat. Clim. Chang. 2025, 15, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veríssimo, D.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Parsons, E.C.M.; Brooks, T.M.; Cinner, J.E.; Game, E.T.; Garnett, S.T.; Green, J.M.H.; Jones, I.L.; McGowan, J.; et al. Changing Human Behavior to Conserve Biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2024, 49, 485–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Lai, K.; He, L.; Yu, R. Where Are You Is Who You Are? The Geographical Account of Psychological Phenomena. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rentfrew, P.J.; Jokela, M. Geographical Psychology: The Spatial Organization of Psychological Phenomena. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2016, 25, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montello, D.R. Behavioral and Cognitive Geography: Introduction and Overview. In Handbook of Behavioral and Cognitive Geography; Montello, D.R., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.; Davidson, J.; Cameron, L.; Bondi, L. Emotion, Place and Culture; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pile, S. Emotions and Affect in Recent Human Geography. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2010, 35, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeDoux, J.E. The Slippery Slope of Fear. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2013, 17, 155–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mobbs, D.; Adolphs, R.; Fanselow, M.S.; Barrett, L.F.; LeDoux, J.E.; Ressler, K.; Tye, K.M. Viewpoints: Approaches to Defining and Investigating Fear. Nat. Neurosci. 2019, 22, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chuenpagdee, R.; Jentoft, S. Governability Assessment for Fisheries and Coastal Systems: A Reality Check. Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.S.; Scott, T.G.; Stacey, N.; Urquhart, J. (Eds.) Social Wellbeing and the Values of Small-Scale Fisheries; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ariely, D. Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions; HarperCollins Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Pligt, J. Decision Making, Psychology of. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 3309–3315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loch, A.; Adamson, D.; Dumbrell, P. The Fifth Stage in Water Management: Policy Lessons for Water Governance. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowdy, J.M. Behavioral Economics and Climate Change Policy. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2008, 68, 632–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiserowitz, A. Climate Change Risk Perception and Policy Preferences: The Role of Affect, Imagery, and Values. Clim. Change 2006, 77, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlüter, M.; Baeza, A.; Dressler, G.; Frank, K.; Groeneveld, J.; Jager, W.; Janssen, M.A.; McAllister, R.R.J.; Müller, B.; Orach, K.; et al. A Framework for Mapping and Comparing Behavioural Theories in Models of Social-Ecological Systems. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 131, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.S.; Small, D.A.; Loewenstein, G. Heart Strings and Purse Strings: Carryover Effects of Emotions on Economic Decisions. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 15, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahneman, D. Thinking, Fast and Slow; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J. Designing with the Mind in Mind; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, E.A.; Smith, A.D.M.; Smith, D.C.; van Putten, I.E. Human Behaviour: The Key Source of Uncertainty in Fisheries Management. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergseth, B.J. Effective Marine Protected Areas Require a Sea Change in Compliance Management. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 75, 1178–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosch, T. Affect and Emotions as Drivers of Climate Change Perception and Action: A Review. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2021, 42, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergseth, B.J.; Arias, A.; Barnes, M.L.; Caldwell, I.; Datta, A.; Gelcich, S.; Ham, S.H.; Lau, J.D.; Ruano-Chamorro, C.; Smallhorn-West, P.; et al. Closing the Compliance Gap in Marine Protected Areas with Human Behavioural Sciences. Fish Fish. 2023, 24, 695–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, J.; Jasper, J.M.; Polletta, F. (Eds.) Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chuenpagdee, R. Interactive Governance for Marine Conservation: An Illustration. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2011, 87, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenpagdee, R. Transdisciplinary Perspectives on Ocean Governance. In The Future of Ocean Governance and Capacity Development; International Ocean Institute—Canada, Ed.; Brill|Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruby, R.L.; Fairbanks, L.; Acton, L.; Artis, E.; Campbell, L.M.; Gray, N.J.; Wilson, K. Conceptualizing Social Outcomes of Large Marine Protected Areas. Coast. Manag. 2017, 45, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhl, E.K.; Esteves Dias, A.C.; Armitage, D. Experiences with Governance in Three Marine Conservation Zoning Initiatives: Parameters for Assessment and Pathways Forward. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nightingale, A.J. The Embodiment of Nature: Fishing, Emotion, and the Politics of Environmental Values. In Human-Environment Relations; Brady, E., Phemister, P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, A.J. Fishing for Nature: The Politics of Subjectivity and Emotion in Scottish Inshore Fisheries Management. Environ. Plan. A 2013, 45, 2362–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.S.; Li, Y.; Valdesolo, P.; Kassam, K.S. Emotion and Decision Making. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 799–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Battista, W.; Romero-Canyas, R.; Smith, S.L.; Fraire, J.; Effron, M.; Larson-Konar, D.; Fujita, R. Behavior Change Interventions to Reduce Illegal Fishing. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018, 5, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santamaría, A.; Euán Ávila, J.I.; Munguia-Rosas, M.A.; Saldívar-Lucio, R.; Fraga, J. Environmental Variability and Governance: The Fishery of Octopus maya in Yucatan, Mexico. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1018728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severin, M.I.; Raes, F.; Notebaert, E.; Lambrecht, L.; Everaert, G.; Buysse, A. A Qualitative Study on Emotions Experienced at the Coast and Their Influence on Well-Being. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 902122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, N.A.; Ross, H.; Lynam, T.; Perez, P.; Leitch, A. Mental Models: An Interdisciplinary Synthesis of Theory and Methods. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuenpagdee, R.; De La Cruz-Modino, R.; Barragán-Paladines, M.J.; Glikman, J.A.; Fraga, J.; Jentoft, S.; Pascual-Fernández, J.J. Governing from Images: Marine Protected Areas as Case Illustrations. J. Nat. Conserv. 2020, 53, 125756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrieber, M.A.; Chuenpagdee, R.; Jentoft, S. Blue Justice and the Co-Production of Hermeneutical Resources for Small-Scale Fisheries. Mar. Policy 2022, 137, 104959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blythe, J.; Baird, J.; Bennett, N.; Dale, G.; Nash, K.L.; Pickering, G.; Wabnitz, C.C.C. Fostering ocean empathy through future scenarios. People Nat. 2021, 3, 1284–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hidalgo, M. The Politics of Reflexivity: Subjectivities, Activism, Environmental Conflict and Gestalt Therapy in Southern Chiapas. Emot. Space Soc. 2017, 25, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uffman-Kirsch, L.B.; Richardson, B.J.; Van Putten, E.I. A New Paradigm for Social License as a Path to Marine Sustainability. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 571373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, R.; Moffat, K. Constructing the Meaning of Social Licence. Soc. Epistemol. 2014, 28, 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.; Oh, C.H.; Shapiro, D. Can Corporate Social Responsibility Lead to Social License? A Sentiment and Emotion Analysis. J. Manag. Stud. 2022, 61, 445–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.R.; Schweitzer, M.E. Feeling and Believing: The Influence of Emotion on Trust. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2005, 88, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbalet, J.M. Social Emotions: Confidence, Trust, and Loyalty. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy 1996, 16, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Misunderstandings and Implications | Evidence-Based Alternative Positions |

|---|---|

| Emotions can be rejected in favor of the dominant rationality paradigm. Emotions are either unknowable or unreliable for use in marine conservation and ocean sustainability and policy research. This is a rationality bias. | Technology (fMRI) shows emotion function within the brain. Biochemistry and physiology can track emotions within the body. Emotions can be observed to influence attitudes and behaviors Explicit emotions can be categorized and characterized using intensity, valence. |

| The experience of individual emotions is sometimes seen as independent from collective experiences and actions, and thus on aggregate, rational decision-making can be anticipated. This is the predictability bias. | Emotional coherence within a group, across different individuals, is necessary for the group to decide. Emotions are dynamic, shared and transferred through social interaction including about the environment Emotions drive social, cultural, and environmental change and vice versa, through individual and group decision-making |

| The influence of emotions on behavior and human activity are sometimes seen discounted as context, along with the cultural and social processes in which the emotions are based. This is a context-ignorance bias | Emotions are inextricably linked to the cultural, social, economic, and political structures and processes that are informed by and shape environmental outcomes Emotions are mediating, informing, and shaping relationships people have with one another on coasts and oceans, and they have with coastal and marine resources Emotions are source and expression of behaviors that shape governance outcomes, conflict and cooperation |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Andrews, E.J.; Wolfe, S.E. Emotions for Sustainable Oceans: Implications for Marine Conservation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167511

Andrews EJ, Wolfe SE. Emotions for Sustainable Oceans: Implications for Marine Conservation. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167511

Chicago/Turabian StyleAndrews, Evan J., and Sarah E. Wolfe. 2025. "Emotions for Sustainable Oceans: Implications for Marine Conservation" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167511

APA StyleAndrews, E. J., & Wolfe, S. E. (2025). Emotions for Sustainable Oceans: Implications for Marine Conservation. Sustainability, 17(16), 7511. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167511