Connecting SDG 2: Zero Hunger with the Other SDGs—Teaching Food Security and the SDGs Interdependencies in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Global Context and Justification

- encourages empathy and global responsibility;

- develops strategic analysis skills;

- prepares students for professional reality, where decisions rarely affect a single area;

- stimulates creativity, interdisciplinarity, and thinking “out of the box”;

- meets international requirements for transformative learning.

- think systemically;

- understand complex causal relationships;

- can build integrative and sustainable solutions;

- are able to anticipate risks, conflicts, or side effects.

1.2. Innovation in Education

1.3. Research Objectives and Questions

- To what extent does the proposed educational activity contribute to developing understanding of the concept of SDGs and the interdependencies between them?

- What is the perceived impact of this method on the formation of students’ systemic thinking?

- What are the self-reported effects on personal food behaviors, especially regarding diet and reducing food waste?

- How do students’ perceptions vary?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background—Literature and Global Context

2.1.1. Key Data and Conclusions from the Sustainable Development Report 2024 on SDG 2

2.1.2. SDG 2—A Central Node in the SDGs Architecture

2.1.3. The Need for Systemic Education About Food Security

2.2. Case-Study Context

- understanding the concept of food security in all its dimensions (availability, accessibility, quality, and stability);

- familiarizing students with the current challenges of food systems at global, European, and national levels;

- developing systemic thinking and the ability to analyze the interdependencies between food security and other areas of sustainable development;

- forming an ethical awareness regarding responsible consumption, reducing food waste, and respecting natural resources.

2.3. Conceptual Pedagogical Model and Learning Environment

2.4. Methodology of Teaching Activity

- how SDG 2 influences the distributed objective;

- how that SDG influences, in turn, SDG 2.

- create a visual presentation

- present the conclusions in a dedicated seminar;

- argue the interdependencies identified by examples, data, or case studies;

- actively participate in discussions and feedback exchange between teams.

- stimulate critical thinking;

- develop the capacity for systemic analysis;

- promote creativity and teamwork;

- develop an ethical awareness in relation to food security;

- raise awareness regarding the role of SDG 2 within the 2030 Agenda.

- theoretical and practical analysis;

- documentation based on FAO, UN, SDSN, Sustainable Development Report resources;

- visual activities (posters, charts, diagrams) along with presentations and debates in seminars.

2.5. Methodology of the Survey Applied to Students

- Section 1—General data (academic year, group, completion date)

- Section 3—Perceived personal impact (5 items, Likert scale 1–5):

- Section 4—Open feedback (2 questions).

- A total of 25 students in the 2023/2024 academic year;

- A total of 21 students in the 2024/2025 academic year.

2.6. Organization of Teaching Activity: Time Allocation, Work Stages, and Applied Method

- internal brainstorming, within each team, to identify ideas;

- collective brainstorming, during seminars assigned to presentations, after each group’s presentation, when the entire group of students was actively involved in completing, commenting on, and discussing the ideas presented.

3. Results

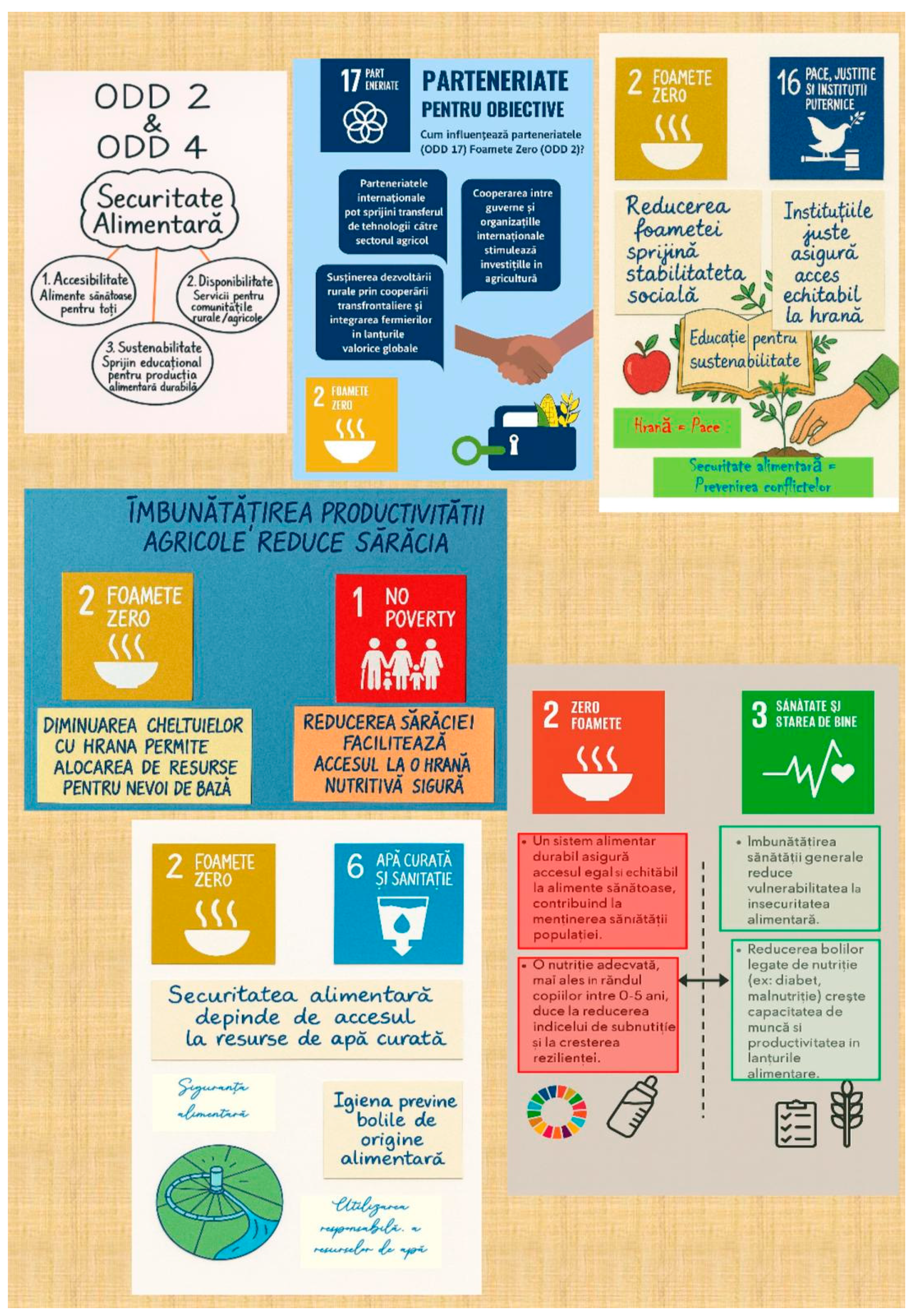

3.1. Visual Diagrams for the Main Connections Between SDG 2 and the Other SDGs

- how SDG 2 contributes to achieving the other SDGs analyzed;

- how that SDG in turn influences food security.

3.2. Analysis of the Major Directions of Influence Between SDG 2 and Other SDGs

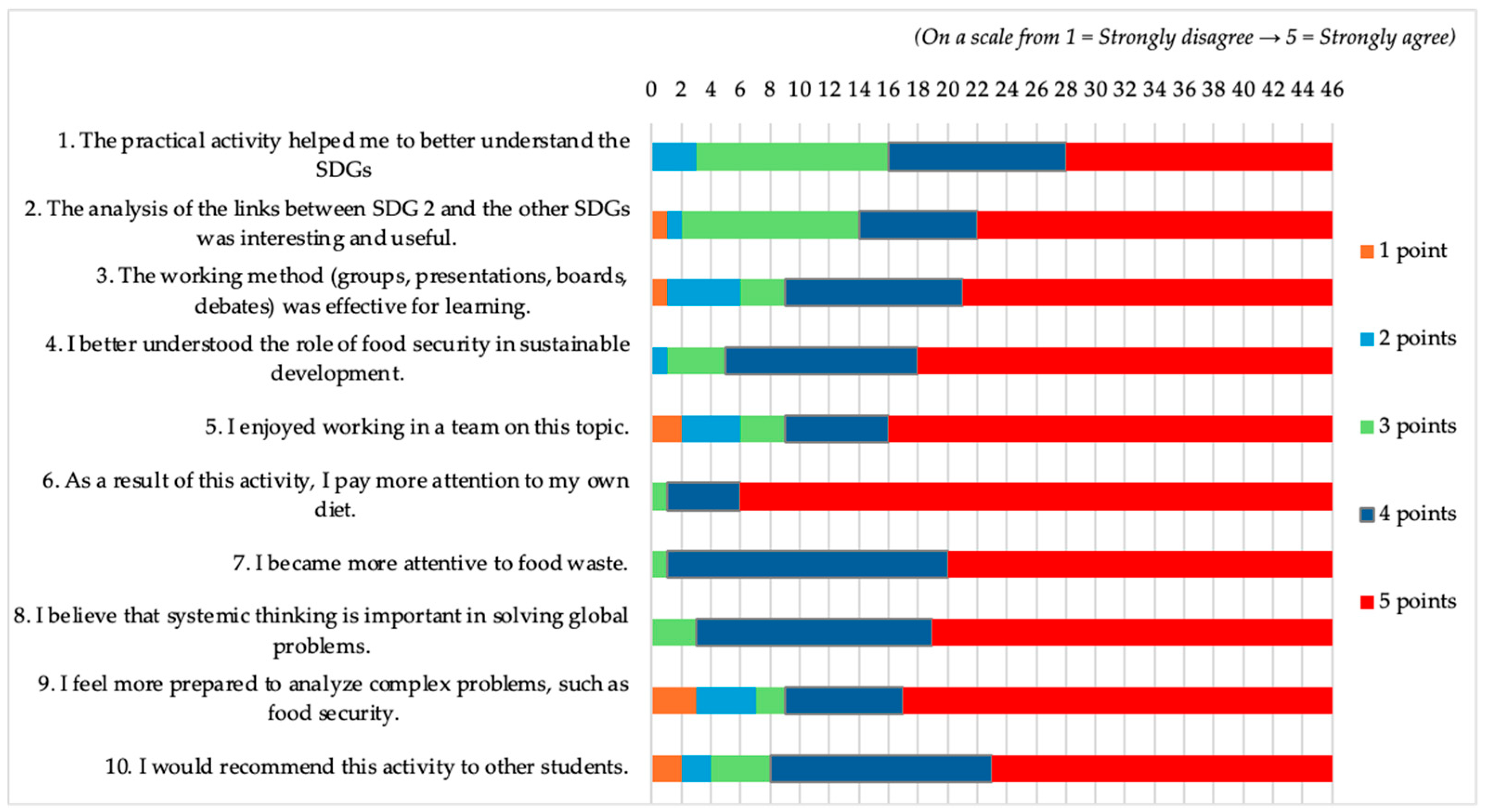

3.3. Evaluation of Students’ Perception of the Usefulness and Impact of Educational Activity

- Understanding the SDGs and their interdependencies. Almost 76.96% of students gave high scores (4 or 5) for the items regarding understanding the SDGs and the connections between SDG 2 and the other SDGs.

- Efficiency of the working method—practical activities such as teamwork, debates, and the creation of thematic boards were considered attractive and effective by 80.43% of respondents.

- Impact on eating behavior—97.83% of students stated that they pay more attention to their own diet and food waste prevention.

- Development of systemic thinking—items related to the ability to analyze complex issues were evaluated with scores by 93.48% of respondents.

4. Discussion

4.1. General Model of Educational Method

4.2. Originality of the Teaching Method

4.3. Transferability of the Method

- -

- in other universities,

- -

- within other study programs,

- -

- in non-formal educational or continuing education contexts.

4.4. How It Supports Education for Food Ethics and Sustainability Literacy

- -

- increased attention to diet;

- -

- reducing food waste;

- -

- understanding one’s own role in the global food chain.

4.5. The Connection of the Method with the Educational Needs of the Future

- Systems thinking and the ability to understand global interdependencies;

- Literacy for sustainability (sustainability literacy);

- Food ethics and responsibility towards resources;

- Communication, argumentation, and collaboration skills;

- Creativity and visual expression;

- Understanding the complexity of food systems.

4.6. Limitations, Shortcomings, and Opportunities for Future Development

- expanding its application in international contexts, with students from other cultures and educational backgrounds;

- using the method starting from other SDGs, depending on specifics of different disciplines;

- integrating digital methods, interactive platforms or multimedia resources to facilitate analyses;

- conducting longitudinal research to investigate the long-term effects on students’ dietary and environmental behaviors;

- developing a guide to good educational practices, including detailed methodology and examples of results from student work.

5. Conclusions

- -

- environmental ethics;

- -

- ethics towards natural resources;

- -

- ethics towards other people, regardless of space, culture, or generation;

- -

- ethics towards the human condition itself, in its fragility and dignity;

- -

- ethics towards those who will come after us—future generations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development: A Roadmap; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Peretz, R.; Dori, D.; Dori, Y.J. Investigating Chemistry Teachers’ Assessment Knowledge via a Rubric for Self-Developed Tasks in a Food and Sustainability Context. Educ. Sci. 2023, 13, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straková, Z.; Cimermanová, I. Critical Thinking Development—A Necessary Step in Higher Education Transformation towards Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2021. Transforming Food Systems for Food Security, Improved Nutrition and Affordable Healthy Diets for All; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G. The SDGs and the UN Summit of the Future; Sustainable Development Report 2024; SDSN: Paris, France; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreoli, V.; Bagliani, M.; Corsi, A.; Frontuto, V. Drivers of Protein Consumption: A Cross-Country Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets Across the Rural–Urban Continuum; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Global Sustainable Development Report 2023, Times of Crisis, Times of Change: Science for Accelerating Transformations to Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2023. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/gsdr/gsdr2023 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Dube, K.; Booysen, R.; Chili, M. Redefining Education and Development: Innovative Approaches in the Era of Sustainable Goals. In Innovative Approaches to Education and Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Väänänen, N.; Kettunen, H.; Posti, A.; Turunen, V. Sustainable Development Agenda 2030 Goals and Early Childhood Education—A Case Study of Project-Based Learning in Higher Education. In Higher Education for Sustainability: Strategies and Cases; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroman, C.; Balan, I.M.; Petroman, I.; Orboi, M.D.; Banes, A.; Trifu, C.; Marin, D. National grading of quality of beef and veal carcasses in Romania according to “EUROP” system. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2009, 7, 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- Dudek, H.; Myszkowska-Ryciak, J. Food Insecurity in Central-Eastern Europe: Does Gender Matter? Sustainability 2022, 14, 5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szentesi, S.G.; Barbu, F.S.; Blaga, R.L.; Bozdog, L.; Breșfelean, V.P. The Role of Perception and Knowledge in Shaping Consumer Behaviour Toward Green Agro-Food Products in Romania and its Effect on Well-Being. Amfiteatru Econ. 2025, 27, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, W.; Shiel, C.; Paço, A.; Mifsud, M.; Ávila, L.; Brandli, L.; Molthan-Hill, P.; Pace, P.; Azeiteiro, U.; Ruiz Vargas, V.; et al. SDGs and Sustainability Teaching at Universities: Falling Behind or Getting Ahead of the Pack? J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bespalyy, S.; Alnazarova, G.; Scalcione, V.N.; Vitliemov, P.; Sichinava, A.; Petrenko, A.; Kaptsov, A. Sustainable Development Awareness and Integration in Higher Education: A Comparative Analysis of Universities in Central Asia, South Caucasus, and the EU. Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, A.; Beasy, K.; Fiedler, T.; Mann, A.; Morrison, B.; Towle, N.; Wood, G.; Doyle, R.; Peterson, C.; Bettiol, S. Common Experiences and Critical Reflections: Embedding Education for Sustainability in Higher Education Curricula Across Disciplines. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopnina, H. Education for the Future? Critical Evaluation of Education for SDGs. J. Environ. Educ. 2020, 51, 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redman, A.; Wiek, A. Competencies for Advancing Transformations Towards Sustainability. Front. Educ. 2021, 6, 785163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencia, A.D.; Balan, I.M. Reevaluating Economic Drivers of Household Food Waste: Insights, Tools, and Implications Based on European GDP Correlations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Tripathi, S.K.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.; Giné-Garriga, R.; Orlovic Lovren, V.; Willats, J. Using the SDGs Towards a Better Understanding of Sustainability Challenges. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2018, 26, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulla, K.; Filho, W.L.; Lardjane, S.; Sommer, J.H.; Borgemeister, C. Sustainable Development Education in the Context of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2020, 27, 458–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SDSN. Accelerating Education for the SDGs in Universities: A Guide for Universities, Colleges, and Tertiary and Higher Education Institutions; Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN): New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Drumm, E. Implementing the SDG Stimulus; Sustainable Development Report 2023; Dublin University Press: Dublin, Ireland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang-Wen, Z.; Murshed, M.; Siddik, A.B.; Alam, M.S.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Mahmood, H. Achieving the objectives of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals Agenda: Causalities between economic growth, environmental sustainability, financial development, and renewable energy consumption. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 680–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCollum, D.L.; Echeverri, L.G.; Busch, S.; Pachauri, S.; Parkinson, S.; Rogelj, J.; Krey, V.; Minx, J.C.; Nilsson, M.; Stevance, A.S.; et al. Connecting the sustainable development goals by their energy inter-linkages. Environ. Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 033006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zugravu, C.A.; Pogurschi, E.N.; Patrascu, E.; Iacob, P.D.; Nicolae, C. Attitudes toward food additives. A pilot Study. The Annals of the University Dunarea de Jos of Galati. Fasc. VI-Food Technol. 2017, 4, 50–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mateoc Sirb, N.; Otiman, P.I.; Mateoc, T.; Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. Balance of Red Meat in Romania—Achievements and Perspectives. In From Management of Crisis to Management in a Time of Crisis, Proceedings of the 5th Review of Management and Economic Engineering International Management Conference, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 22–24 September 2016; Todesco Publishing House: Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2016; pp. 388–394. Available online: https://www.webofscience.com/wos/woscc/full-record/WOS:000385997200048 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Bali Swain, R.; Yang-Wallentin, F. Achieving Sustainable Development Goals Predicaments and Strategies. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2019, 27, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDPI Books. Book Series Transitioning to Sustainability ISSN 2624-9324 (Print) ISSN 2624-9332 (Online). Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/books/book-series/1152-transitioning-to-sustainability (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Dörgő, G.; Sebestyén, V.; Abonyi, J. Evaluating the Interconnectedness of the Sustainable Development Goals Based on the Causality Analysis of Sustainability Indicators. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Education for Sustainable Development Learning to Act for People and Planet. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/sustainable-development/education (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Rinovetz, A.; Rinovetz, Z.A.; Mateescu, C.; Trasca, T.I.; Jianu, C.; Jianu, I. Rheological characterisation of the fractions separated from pork lards through dry fractionation. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, P.D.; Larson, N.M. The Hunger of Nations: An empirical study of inter-relationships among the SDGs. J. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 12, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guba, E.G. Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. ECTJ 1981, 29, 75–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.; Yang, S.-W. Likert-Type Scale. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salasan, C.; Balan, I.M. The environmentally acceptable damage and the future of the EU’s rural development policy. In Economics and Engineering of Unpredictable Events; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pogurschi, E.N.; Munteanu, M.; Nicolae, C.G.; Marin, M.; Zugravu, C.A. Rural-urban meat consumption in Romania. Sci. Pap. Ser. D Anim. Sci. 2018, 61, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Trasca, T.I.; Groza, I.; Rinovetz, A.; Rivis, A.; Radoi, B.P. The study of the behaviour of polytetrafluorethylene dies for pasta extrusion comparative with bronze dies. Rev. Mater. Plast 2007, 44, 307–309. [Google Scholar]

- Times Higher Education. Top Universities for Solving World Hunger in 2024. 2024. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/impactrankings/zero-hunger (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- United Nations. Final List of Proposed Sustainable Development Goal Indicators. 2016. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/11803Official-List-of-Proposed-SDG-Indicators.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024. Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms; FAO/IFAD/UNICEF/WFP/WHO: Rome, Italy, 2024. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cd1254en (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Chiurciu, I.-A.; Vlad, I.M.; Stoicea, P.; Zaharia, I.; David, L.; Soare, E.; Fîntîneru, G.; Micu, M.M.; Dinu, T.A.; Tudor, V.C.; et al. Romanian Meat Consumers’ Choices Favour Sustainability? Sustainability 2024, 16, 11193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute of Romania. Food Security in Romania and the European Union. Challenges and Perspectives; Study Carried Out within the SPOS 2022 Project; European Institute of Romania: Bucharest, Romania, 2023. Available online: https://ier.gov.ro/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/Studiul-1_SPOS-2022_Securitatea-alimentara_Final.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Romanian Academy, Presidential Commission for Public Policies for the Development of Agriculture. National Strategic Framework for the Sustainable Development of the Agri-Food Sector and Rural Space in the Period 2014–2020–2030; Food and Agriculture Organization: Rome, Italy, 2013. Available online: https://acad.ro/forumuri/doc2013/d0701-02StrategieCadrulNationalRural.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- García-Juanatey, A.; De Vita, I. Challenges to SDG 2 on Zero Hunger: Becoming aware of the vulnerabilities of the global food system. In Geoeconomics of the SDGs; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 294–309. [Google Scholar]

- Allahyari, M.; Poursaeed, A. Sustainable Agriculture: Implication for SDG2 (Zero Hunger). In Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN SDGs; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, D.R.; Saxena, A.D.; Tupkar, N.J.; Karim, F.A.; Irving, A.L. Understanding Sustainable Development Goal 2: Zero Hunger. In Smart Technologies for SDGs; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Otekunrin, O.A. Countdown to the 2030 global Goals: A bibliometric analysis of research trends on SDG 2–zero hunger. Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J. 2023, 11, 1338–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, B.; Rundshagen, V. Paradigm shift to implement SDG 2 (end hunger): A humanistic management lens on the education of future leaders. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2020, 18, 100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, L.M.; Domingues, J.P.; Dima, A.M. Mapping the SDGs Relationships. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenland, S.J.; Saleem, M.; Misra, R.; Nguyen, N.; Mason, J. Reducing SDG complexity and informing environmental management education via an empirical six-dimensional model of sustainable development. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farquharson, C.; McNally, S.; Tahir, I. Education Inequalities. Oxf. Open Econ. 2024, 3 (Suppl. S1), i760–i820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahyari, M.S.; Sadeghzadeh, M. Agricultural Extension Systems Toward SDGs 2030: Zero Hunger. In Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN SDGs; Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Özuyar, P.G., Wall, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Evaluation of Cohesion Policy in the Member States. 2024. Available online: https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/stories/s/suip-d9qs (accessed on 1 April 2025).

- Grigoroiu, M.C.; Țurcanu, C.; Constantin, C.P.; Tecău, A.S.; Tescașiu, B. The Impact of EU-Funded Educational Programs on the Socio-Economic Development of Romanian Students: A Multidimensional Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Paredes, G.X.; Juarez-Alvarez, C.R.; Cuya-Zevallos, C.; Mamani-Machaca, E.S.; Esquicha-Tejada, J.D. Enhancing Social Innovation Through Design Thinking, Challenge-Based Learning, and Collaboration in University Students. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Guo, L. Constructing the Early-Stage Framework of Cultural Identity Enlightenment in Kindergarten Heritage Education. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Sustainable Development in the European Union. Monitoring Report on Progress Towards the SDGs in an EU Context. 2022 Edition. 2022. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/15234730/15242025/KS-09-22-019-EN-N.pdf/a2be16e4-b925-f109-563c-f94ae09f5436?t=1667397761499 (accessed on 5 April 2025).

- European Commission. EU Actions to Enhance Global Food Security. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/eu-actions-enhance-global-food-security_en (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Varzakas, T.; Smaoui, S. Global Food Security and Sustainability Issues: The Road to 2030 from Nutrition and Sustainable Healthy Diets to Food Systems Change. Foods 2024, 13, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzoni, L.; Centemeri, L.; Benegiamo, M.; Panico, C. A new food security approach? Continuity and novelty in the European Union’s turn to preparedness. Agric. Hum. Values 2025, 42, 89–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty. European Union Statement of Commitments for the Global Alliance Against Hunger and Poverty. Statements of Commitment–Tentative Final Draft. Available online: https://globalallianceagainsthungerandpoverty.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/EU-SoC-Approved.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Ahn, S.; Ames, A.J.; Myers, N.D. A review of meta-analyses in education: Methodological strengths and weaknesses. Rev. Educ. Res. 2012, 82, 436–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S. The advantages and disadvantages of using qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in language “testing and assessment” research: A literature review. J. Educ. Learn. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salasan, C.; Balan, I. Suitability of a quality management approach within the public agricultural advisory services. Qual.-Access Success 2014, 15, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Petroman, I.; Untaru, R.C.; Petroman, C.; Orboi, M.D.; Băneș, A.; Marin, D.; Bălan, I.; Negruț, V. The influence of differentiated feeding during the early gestation status on sows prolificacy and stillborns. J. Food Agric. Environ. 2011, 9, 223–224. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A.; Smedescu, D.; Mack, G.; Fintineru, G. Is there a nitrogen deficit in Romanian agriculture? AgroLife Sci. J. 2017, 6. Available online: https://agrolifejournal.usamv.ro/index.php/agrolife/article/view/177 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Vlad, I.M.; Butcaru, A.C.; Fintineru, G.; Badulescu, L.; Stanica, F.; Toma, E. Mapping the Preferences of Apple Consumption in Romania. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO). Hunger and Food Insecurity. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/hunger/en (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Cripps, K.; Thondre, P.S. (Eds.) Higher Education and SDG2: Zero Hunger (Higher Education and the Sustainable Development Goals); Emerald Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2024; pp. 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniepert, M.; Fintineru, G. Blockchain technology in food-chain management—An institutional economic perspective. Sci. Pap. Ser. Manag. Econ. Eng. Agric. Rural Dev. 2018, 18, 183–202. [Google Scholar]

| Work Stage | Description | Time Allocation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Theoretical presentation of the SDGs and explanation of the working methodology | 2 h |

| 2 | Organizing of working teams (preferably 3 students each), assignment of SDGs and initial brainstorming within each team | 1 h |

| 3 | Team documentation based on recommended sources (FAO, UN, SDSN, Sustainable Development Report, scientific articles) | 4 h |

| 4 | Analysis of the interdependencies between SDG 2 and the assigned SDG, selection of ideas, preparation of visual materials | 3 h |

| 5 | Public presentation of results, collective brainstorming, debates, and interactive feedback | 4 h |

| Total | 14 h | |

| Influence of SDG2 on Other SDGs | SDG | Influence of SDGs on SDG2 | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

|  |

| [4,11,36,37,54] |

|  |

| [4,5,8,13] |

|  |

| [7,36,38,39,40] |

|  |

| [4,5,7,32,41,42] |

|  |

| [39,43,44] |

|  |

| [33,45,46] |

|  |

| [7,40,46,47,48,49] |

|  |

| [6,7,13,51] |

|  |

| [7,52] |

|  |

| [55,56] |

|  |

| [5,6,7,30] |

|  |

| [4,7,43] |

|  |

| [7,41,43] |

|  |

| [1,7,41] |

|  |

| [1,7,40,41] |

|  |

| [7,41,43] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Balan, I.M.; Trasca, T.I.; Ocnean, M.; Horablaga, A.; Mateoc-Sirb, N.; Salasan, C.; Tiu, J.V.; Radoi, B.P.; Lile, R.A.; Firu Negoescu, G.A. Connecting SDG 2: Zero Hunger with the Other SDGs—Teaching Food Security and the SDGs Interdependencies in Higher Education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167496

Balan IM, Trasca TI, Ocnean M, Horablaga A, Mateoc-Sirb N, Salasan C, Tiu JV, Radoi BP, Lile RA, Firu Negoescu GA. Connecting SDG 2: Zero Hunger with the Other SDGs—Teaching Food Security and the SDGs Interdependencies in Higher Education. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167496

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalan, Ioana Mihaela, Teodor Ioan Trasca, Monica Ocnean, Adina Horablaga, Nicoleta Mateoc-Sirb, Cosmin Salasan, Jeni Veronica Tiu, Bogdan Petru Radoi, Raul Adrian Lile, and Gheorghe Adrian Firu Negoescu. 2025. "Connecting SDG 2: Zero Hunger with the Other SDGs—Teaching Food Security and the SDGs Interdependencies in Higher Education" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167496

APA StyleBalan, I. M., Trasca, T. I., Ocnean, M., Horablaga, A., Mateoc-Sirb, N., Salasan, C., Tiu, J. V., Radoi, B. P., Lile, R. A., & Firu Negoescu, G. A. (2025). Connecting SDG 2: Zero Hunger with the Other SDGs—Teaching Food Security and the SDGs Interdependencies in Higher Education. Sustainability, 17(16), 7496. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167496