Promoting Conservation Intentions Through Humanized Messaging in Green Advertisements: The Mediation Roles of Empathy and Responsibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Green Ads Utilizing Humanized Messaging

2.2. Self-Expansion Theory and Dual-Process Theory

2.2.1. Self-Expansion Theory

2.2.2. Dual-Process Theory

2.3. Empathy and Perceived Responsibility

3. Research Design and Methodology

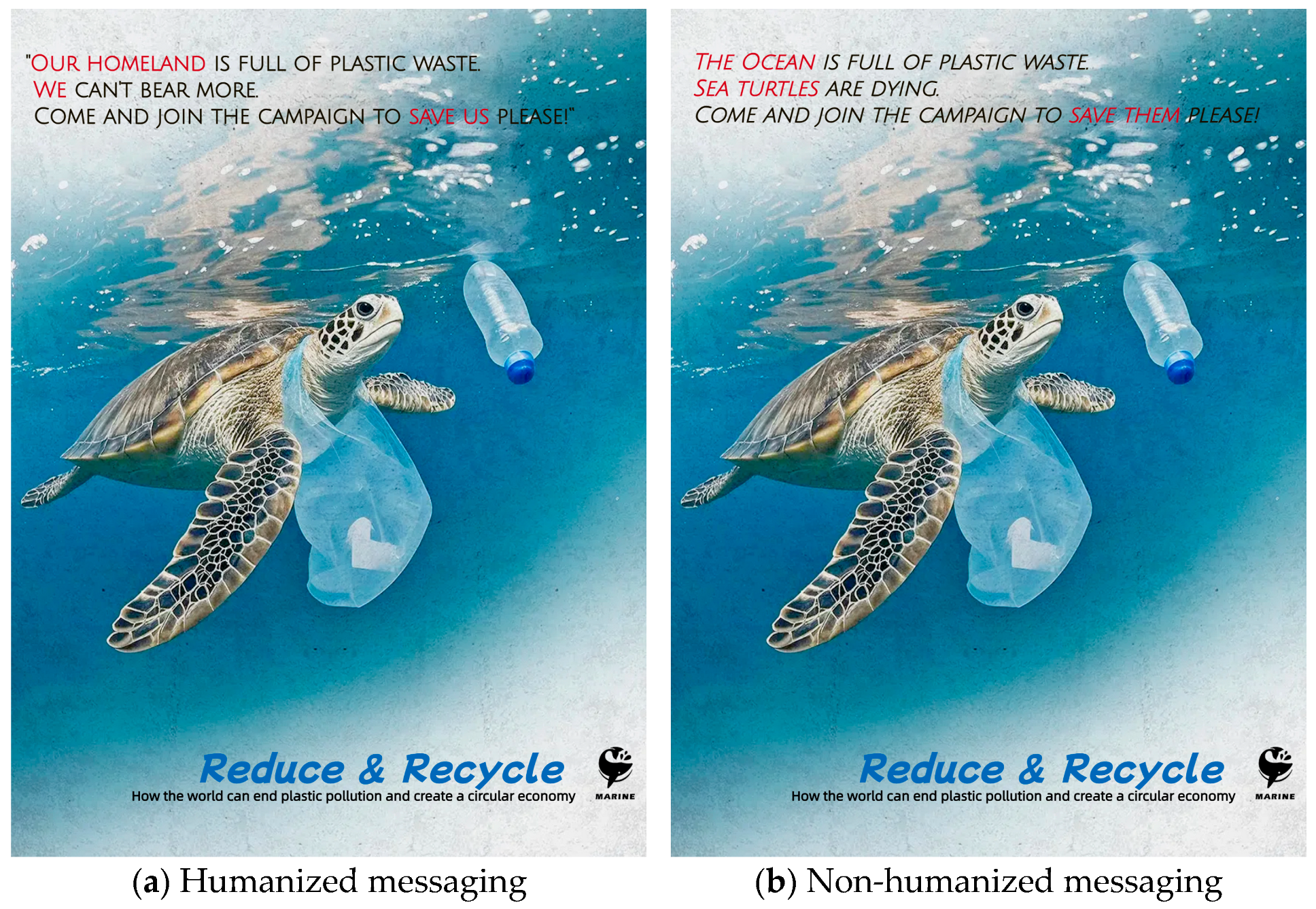

3.1. Pretest: Advertisement Stimulus

3.2. Main Study

3.2.1. Participants and Procedures

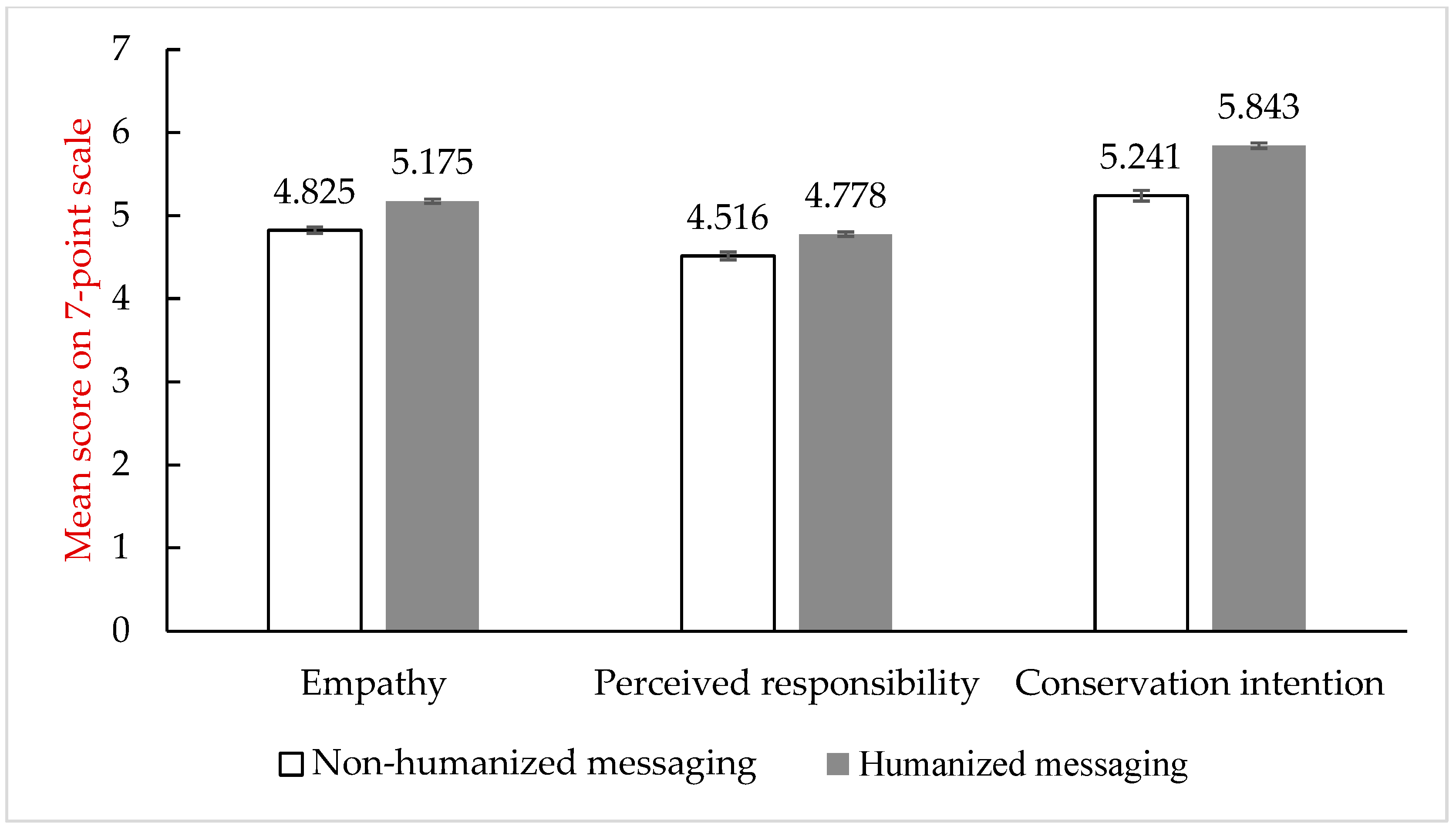

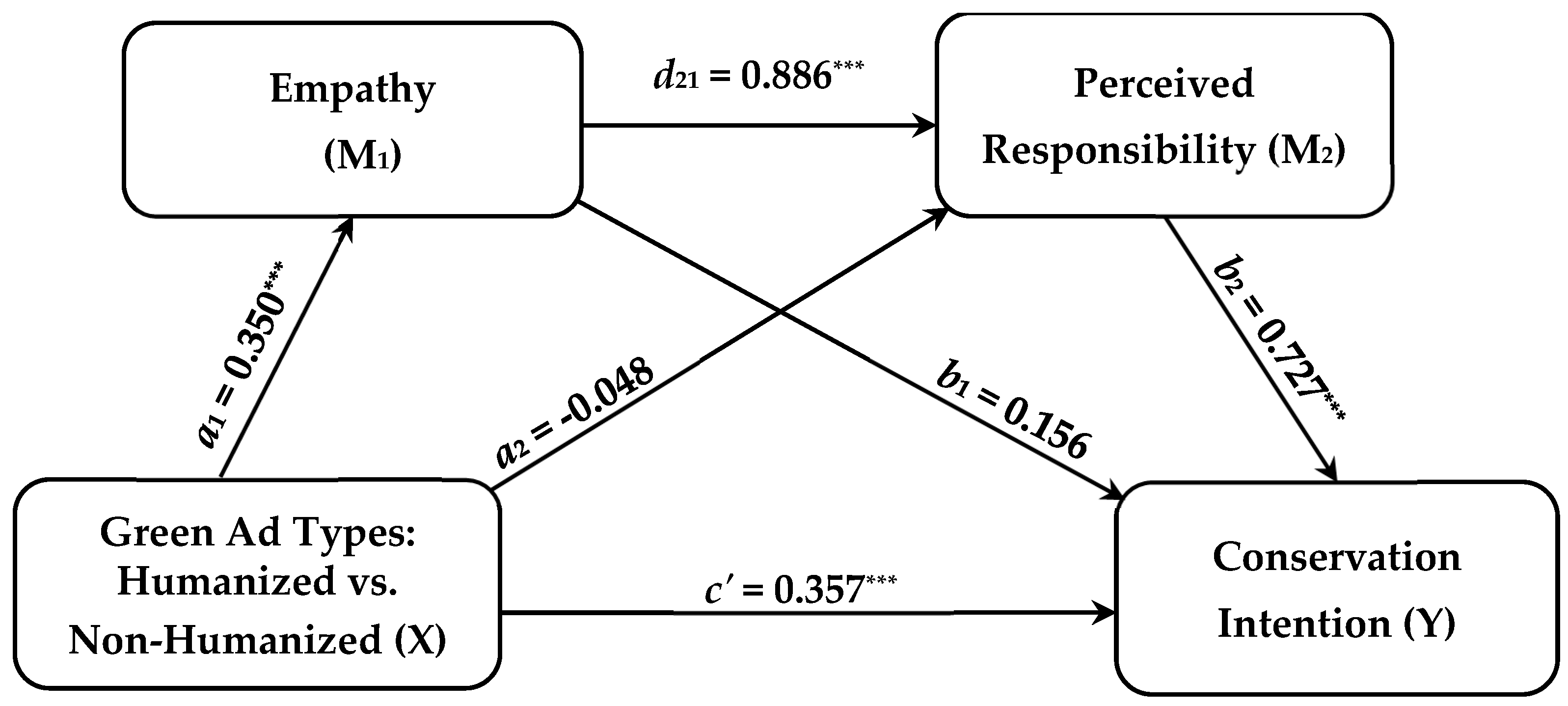

3.2.2. Results

4. General Discussion and Implications

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial Implications

4.3. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Overview of Full Text for Anthropomorphism Manipulation

| Humanized messaging “Our homeland is full of plastic waste. We can’t bear more. Come and join the campaign to save us please!” |

| Non-humanized messaging The ocean is full of plastic waste. Sea turtles are dying. Come and join the campaign to save them please! |

Appendix B. Overview of Measurement Items

| Variables | Measurement Items |

| Empathy [8] | 1. I feel sympathetic toward the sea turtle 2. I am concerned about the sea turtle 3. I feel compassionate toward the sea turtle 4. I feel soft-hearted toward the sea turtle 5. I feel tender toward the sea turtle (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) |

| Perceived responsibility [49] | 1. It is my responsibility to provide aid for the sea turtle 2. I should be expected to help the sea turtle 3. We should be responsible for helping the marine environment. 4. I feel it is up to me to help the sea turtle (1 = “strongly disagree”, 7 = “strongly agree”) |

| Conservation intention [58] | How likely/inclined/willing are you to take part in the Reduce & Recycle campaign? (1 = “highly unlikely,” and 7 = “highly likely”) (1 = “not very inclined,” and 7 = “very inclined”) (1 = “very unwilling,” and 7 = “very willing”) |

References

- Eriksen, M.; Cowger, W.; Erdle, L.; Coffin, S.; Villarrubia-Gómez, P.; Moore, C. A growing plastic smog, now estimated to be over 170 trillion plastic particles afloat in the world’s oceans-Urgent solutions required. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0281596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Climate, Infrastructure and Environment Executive Agency. Protecting Europe’s Seabirds: Tackling Plastic Pollution with LIFE. Available online: https://cinea.ec.europa.eu/news-events/news/protecting-europes-seabirds-tackling-plastic-pollution-life-2024-09-03_en (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- WWF. In Photos: Drowning in Plastics. Available online: https://wwf.org.au/blogs/in-photos-drowning-in-plastics/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Borriello, A. Preferences for microplastic marine pollution management strategies: An analysis of barriers and enablers for more sustainable choices. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 344, 118382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, H.V.; Jones, N.H.; Davies, A.J.; Godley, B.J.; Jambeck, J.R.; Napper, I.E.; Suckling, C.C.; Williams, G.J.; Woodall, L.C.; Koldewey, H.J. The fundamental links between climate change and marine plastic pollution. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 150392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dabiran, E.; Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Grant, G. Virtually human: Anthropomorphism in virtual influencer marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2024, 79, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yang, Z.; Su, X. Too anthropomorphized to keep distance: The role of social psychological distance on meat inclinations. Appetite 2024, 196, 107272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Wong, N.; Huang, M. Does relationship matter? How social distance influences perceptions of responsibility on anthropomorphized environmental objects and conservation intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 95, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, H.-K.; Kim, H.J.; Aggarwal, P. Helping fellow beings: Anthropomorphized social causes and the role of anticipatory guilt. Psychol. Sci. 2014, 25, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; Simpson, B. When Do (and Don’t) Normative Appeals Influence Sustainable Consumer Behaviors? J. Mark. 2013, 77, 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, E.Y. Saving Mr. Water: Anthropomorphizing water promotes water conservation. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 174, 105814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketron, S.; Naletelich, K. Victim or beggar? Anthropomorphic messengers and the savior effect in consumer sustainability behavior. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Basso, F. “Animals are friends, not food”: Anthropomorphism leads to less favorable attitudes toward meat consumption by inducing feelings of anticipatory guilt. Appetite 2019, 138, 153–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Root-Bernstein, M.; Douglas, L.; Smith, A.a.; Verissimo, D. Anthropomorphized species as tools for conservation: Utility beyond prosocial, intelligent and suffering species. Biodivers. Conserv. 2013, 22, 1577–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedeke, T.L. Devils, angels or animals: The social construction of otters in conflict over management. In Mad About Wildlife; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.O.; Whitmarsh, L.; Chriost, D.M. The association between anthropomorphism of nature and pro-environmental variables: A systematic review. Biol. Conserv. 2021, 255, 109022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles, A.; Raymond, M.; Lecointre, G. Empathy and compassion toward other species decrease with evolutionary divergence time. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Premack, D. Human and animal cognition: Continuity and discontinuity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 13861–13867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N.; Schroeder, J.; Waytz, A. Motivated Mind Perception: Treating Pets as People and People as Animals. In Objectification and (De)Humanization: 60th Nebraska Symposium on Motivation; Gervais, S.J., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 127–152. [Google Scholar]

- Waytz, A.; Gray, K.; Epley, N.; Wegner, D.M. Causes and consequences of mind perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2010, 14, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.; Puzakova, M.; Rocereto, J.F.; Moriguchi, T. When the Unknown Destination Comes Alive: The Detrimental Effects of Destination Anthropomorphism in Tourism. J. Advert. 2020, 49, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.W.; Aggarwal, P.; McGill, A.L. The 3 C’s of anthropomorphism: Connection, comprehension, and competition. Consum. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 3, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, T.H.; Bakpayev, M.; Yoon, S.; Kim, S. Smiling AI agents: How anthropomorphism and broad smiles increase charitable giving. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 850–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, J.D.; Koo, M.; Hofmann, W. When Temptations Come Alive: How Anthropomorphism Undermines Self-Control. J. Consum. Res. 2015, 42, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puzakova, M.; Kwak, H. Should anthropomorphized brands engage customers? The impact of social crowding on brand preferences. J. Mark. 2017, 81, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, K.T.; Wang, C.Y.; Guchait, P. When normative framing saves Mr. Nature: Role of consumer efficacy in proenvironmental adoption. Psychol. Market. 2021, 38, 1340–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J. Feeding Mr Monkey: Cross-species food ‘exchange’in Japanese monkey parks. In Animals in Person; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 231–253. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, E.N.; Aron, A. Love and expansion of the self: The state of the model. Pers. Relatsh. 1996, 3, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aron, A.; Aron, E.N.; Norman, C. Self-expansion Model of Motivation and Cognition in Close Relationships and Beyond. In Self and Social Identity; Perspectives on Social Psychology; Blackwell Publishing: Malden, MA, USA, 2004; pp. 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, A.; Lewandowski, G.; Branand, B.; Mashek, D.; Aron, E. Self-expansion motivation and inclusion of others in self: An updated review. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2022, 39, 3821–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, W.L.; Gabriel, S.; Hochschild, L. When you and I are “we,” you are not threatening: The role of self-expansion in social comparison. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 82, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Kerviler, G.; Rodriguez, C.M. Luxury brand experiences and relationship quality for Millennials: The role of self-expansion. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 102, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, N.; Choi, D.; Lee, H.K. Exploring Consumer Participation in Brand Metaverse Communities, Focusing on the Metaverse Features—Fantasy Experiences and Self-Expansion. J. Consum. Behav. 2025, 24, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. The structure of environmental concern: Concern for self, other people, and the biosphere. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W.; Shriver, C.; Tabanico, J.J.; Khazian, A.M. Implicit connections with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R.E.; Van Liere, K.D.; Mertig, A.G.; Emmet Jones, R. Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 425–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The connectedness to nature scale: A measure of individuals’ feeling in community with nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Geng, L.; Ye, L.; Zhou, K. “Mother Nature” enhances connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.P.; Lee, S.L.; Chao, M.M. Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connectedness to and protectiveness toward nature. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 49, 514–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, P.; Kannis-Dymand, L.; Mulgrew, K.E.; Schaffer, V.; Peake, S. Empathy and experience: Understanding tourists’ swim with whale encounters. Hum. Dimens. Wildl. 2020, 25, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.B.T.; Stanovich, K.E. Dual-Process Theories of Higher Cognition: Advancing the Debate. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, J. Dual-processing accounts of reasoning, judgment, and social cognition. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008, 59, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chick, C.F. Cooperative versus competitive influences of emotion and cognition on decision making: A primer for psychiatry research. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 273, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, W. Empathizing with nature: The effects of perspective taking on concern for environmental issues-statis. J. Soc. Issues 2002, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berenguer, J. The effect of empathy in proenvironmental attitudes and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2007, 39, 269–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cialdini, R.B.; Brown, S.L.; Lewis, B.P.; Luce, C.; Neuberg, S.L. Reinterpreting the empathy–altruism relationship: When one into one equals oneness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1997, 73, 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.M.; Li, B.J. So far yet so near: Exploring the effects of immersion, presence, and psychological distance on empathy and prosocial behavior. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2023, 176, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirowska, A.; Arsenyan, J. Sweet escape: The role of empathy in social media engagement with human versus virtual influencers. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2023, 174, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winterich, K.P.; Zhang, Y. Accepting inequality deters responsibility: How power distance decreases charitable behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2014, 41, 274–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, P.; Wu, W.; Huo, C. Crucial to Me and my society: How collectivist culture influences individual pro-environmental behavior through environmental values. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 454, 142211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syropoulos, S.; Markowitz, E. Responsibility towards future generations is a strong predictor of proenvironmental engagement. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, B.; Gunarathne, N.; Gaskin, J.; Ong, T.S.; Ali, M. Environmental corporate social responsibility and pro-environmental behavior: The effect of green shared vision and personal ties. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelo, N.; White, K.; Goode, M.R. Nature promotes self-transcendence and prosocial behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2021, 76, 101639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wispé, L. The distinction between sympathy and empathy: To call forth a concept, a word is needed. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 50, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, D.; Tong, Z.P.; Tian, J.C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.X.; Sun, Y. Anthropomorphic Strategies Promote Wildlife Conservation through Empathy: The Moderation Role of the Public Epidemic Situation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P.; McGill, A.L. Is that car smiling at me? Schema congruity as a basis for evaluating anthropomorphized products. J. Consum. Res. 2007, 34, 468–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyvis, T.; Van Osselaer, S.M.J. Increasing the Power of Your Study by Increasing the Effect Size. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 1157–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.; MacDonnell, R.; Dahl, D.W. It’s the mind-set that matters: The role of construal level and message framing in influencing consumer efficacy and conservation behaviors. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 48, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Mattila, A.S.; Hanks, L. Investigating the impact of surprise rewards on consumer responses. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 50, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; Podsakoff, N.P.; Williams, L.J.; Huang, C.; Yang, J. Common method bias: It’s bad, it’s complex, it’s widespread, and it’s not easy to fix. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2024, 11, 17–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 3rd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; McGill, A.L. Gaming with Mr. Slot or gaming the slot machine? Power, anthropomorphism, and risk perception. J. Consum. Res. 2011, 38, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. Blue Planet II. Available online: https://www.bbcearth.com/shows/blue-planet-ii (accessed on 20 May 2025).

- Lange, F.; Dewitte, S. Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 63, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhang, K. Going for Equality: How Power States Influence Consumers’ Preference For Advertisements With Right-Enhancing Versus Suffering-Reducing Appeals. Psychol. Mark. 2025, 42, 1264–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, C.D.; Nguyen, B.N.; Doan, X.H.; Nguyen, V.H.; Vu, A.T. “I do believe in karma”: Understanding consumers’ pro-environmental consumption with an integrated framework of theory of planned behavior, norm activation model and self-determination theory. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2024, 35, 270–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, N. The Effects of Emotion, Spokesperson Type, and Benefit Appeals on Persuasion in Health Advertisements: Evidence from Macao. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Variable | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 263 | 52.10% |

| Female | 242 | 47.90% |

| Age | ||

| 18–30 years | 149 | 29.50% |

| 31–45 years | 189 | 37.43% |

| 46–60 years | 167 | 33.07% |

| Education level | ||

| Below high school | 126 | 24.95% |

| Junior college | 140 | 27.72% |

| Bachelor’s degree | 169 | 33.47% |

| Master’s degree and above | 70 | 13.86% |

| Occupation | ||

| Students | 116 | 22.97% |

| State-owned enterprises or public servant | 139 | 27.52% |

| Private enterprise staff | 151 | 29.91% |

| Freelance | 99 | 19.60% |

| Green ad Types (X) | Mean | SD | t | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Empathy (M1) | 4.825 | 0.580 | −7.912 | 446.781 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 5.175 | 0.398 | ||||

| 0 | Responsibility (M2) | 4.516 | 0.767 | −4.804 | 382.021 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 4.778 | 0.404 | ||||

| 0 | Conservation (Y) | 5.241 | 1.021 | −8.342 | 375.573 | < 0.001 |

| 1 | 5.843 | 0.522 |

| Panel A: | Empathy (M1) | Perceived Responsibility (M2) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | t | p | Coeff. | SE | t | p | ||

| Constant | iM1 | 4.825 | 0.031 | 154.230 | <0.001 | iM2 | 0.243 | 0.187 | 1.304 | 0.193 |

| Green ad type (X) | a1 | 0.350 | 0.044 | 7.906 | <0.001 | a2 | −0.048 | 0.040 | −1.193 | 0.234 |

| Empathy (M1) | d21 | 0.886 | 0.038 | 23.138 | <0.001 | |||||

| R2 | 0.111 | 0.537 | ||||||||

| F (1, 503) = 62.505, p < 0.001 | F (2, 502) = 291.425, p < 0.001 | |||||||||

| Conservation Intention (Y) | ||||||||||

| Antecedent | Coeff. | SE | t | p | ||||||

| Constant | iy | 1.207 | 0.279 | 4.334 | <0.001 | |||||

| Green ad type (X) | c’ | 0.357 | 0.060 | 5.928 | <0.001 | |||||

| Empathy (M1) | b1 | 0.156 | 0.082 | 1.903 | 0.058 | |||||

| Responsibility (M2) | b2 | 0.727 | 0.067 | 10.928 | <0.001 | |||||

| R2 | 0.461 | |||||||||

| F (3, 501) = 142.924, p < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Panel B: | ||||||||||

| Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | |||||||

| Total effect of X on Y c | 0.601 | 0.072 | 0.460 | 0.743 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.121 | |||||||||

| F (1, 503) = 69.434, p < 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Direct effect of X on Y c′ | 0.357 | 0.060 | 0.238 | 0.475 | ||||||

| Total indirect effect | 0.283 | 0.054 | 0.179 | 0.392 | ||||||

| Ind1 (X→ M1→ Y) | 0.063 | 0.038 | −0.003 | 0.145 | ||||||

| Ind2 (X→ M1→ Y) | −0.040 | 0.033 | −0.103 | 0.026 | ||||||

| Ind3 (X→ M1→ M2-→ Y) | 0.261 | 0.042 | 0.182 | 0.344 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Jiang, A.L. Promoting Conservation Intentions Through Humanized Messaging in Green Advertisements: The Mediation Roles of Empathy and Responsibility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167465

Chen Y, Jiang AL. Promoting Conservation Intentions Through Humanized Messaging in Green Advertisements: The Mediation Roles of Empathy and Responsibility. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167465

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yangyang, and Alice Ling Jiang. 2025. "Promoting Conservation Intentions Through Humanized Messaging in Green Advertisements: The Mediation Roles of Empathy and Responsibility" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167465

APA StyleChen, Y., & Jiang, A. L. (2025). Promoting Conservation Intentions Through Humanized Messaging in Green Advertisements: The Mediation Roles of Empathy and Responsibility. Sustainability, 17(16), 7465. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167465

_Li.png)