1. Introduction

Environmental sustainability is a topic of growing concern, and implementation strategies have been adopted in both corporate policy frameworks and governance. Climate change, environmental degradation, and loss of biodiversity pose critical global threats [

1]. Organizations are under growing pressure to implement adequate environmental management practices (EMPs) that reflect both commitment and efforts towards sustainable development [

2]. Understanding the motivational drivers of EMP adoption and how they impact organizations and their employees’ pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors is a key research area for both academic and corporate strategy [

3].

In developing countries, the oil and gas industry faces especially significant scrutiny with respect to its organizational processes and resulting environmental impact [

4]. Oil companies operate in highly sensitive environmental and ecological zones, and they are often critical to national economies. However, these companies also contribute substantially to resource depletion, environmental pollution, and global carbon emissions [

5]. Adoption of EMPs by oil companies is not only a factor of environmental policy and regulation compliance, but it is also about ethical responsibility, stakeholder engagement, and corporate strategy intent [

6]. The effectiveness of EMPs is rooted in the motivations driving the adoption and implementation of these practices and the extent to which they are internalized by an organization’s culture and employees [

7].

Organizational commitment is reported as a factor in promoting voluntary pro-environmental behavior. A study by Bai et al. [

8] reported voluntary pro-environmental behavior in frontline employees with the moderating role of organizational commitment and perceived corporate social responsibility. Corporate environmental management in the form of green employee empowerment has been found to increase employee motivation towards pro-environmental behavior and job satisfaction among hotel employees [

9]. The use of green human resource management as a form of corporate environmental management initiative was reported to have an encouraging and motivating impact on the hospitality industry workers in Pakistan [

10].

Environmental management practices are motivated by many different factors, which include market competitiveness, employee morale, regulatory compliance, and cost reduction [

11]. External pressures from institutional legislation and customer expectations can prompt organizational compliance with EMPs. However, internal motivations such as corporate vision and ethical values are often associated with more transformative EMPs and environmental sustainability [

12]. The presence of intrinsic organizational motivation towards EMPs is strongly associated with long-term sustainable environmental impact [

13]. Intrinsic organizational motivation is also associated with long-term behavioral and attitudinal change, as well as environmental innovation within organizations [

14]. The interaction between motivation and actual pro-environmental behaviors is not comprehensively understood, especially in developing economies, relative to industrial processes [

15].

This study investigates the role of corporate sustainability motivations and how they impact environmental management practices, pro-environmental attitudes, and recurring environmentally sustainable behaviors among employees of Libya’s oil sector. This study explores the prevalence of organizational EMP motivations and actions of employees within an organization relative to environmental sustainability. By analyzing data from a survey carried out on 405 employees of major oil companies in Libya, this study aims to make an important contribution to the literature. According to the purpose of this study, the following research questions should be answered:

What are the dominant motivations for implementing environmental management in Libyan oil companies?

How do corporate sustainability motivations influence employee pro-environmental attitudes?

To what extent do pro-environmental attitudes translate into recurring pro-environmental behaviors in employees?

The findings presented in this study offer valuable insights into environmental management for the academic literature, policymakers, corporate leaders, and sustainability advocates. Furthermore, it contributes to the discourse on sustainable corporate practices in developing economies where institutional pressures and sociocultural dynamics are significantly different from those in developed economies.

Libya presents a complex context for the examination of environmental sustainability, especially as a dominant oil-producing country. The country has experienced over a decade of conflict, political instability, and institutional fragmentation. These have severely challenged the country’s environmental governance and regulatory enforcement [

16]. Due to this factor, formal environmental oversight is often inconsistent, which leaves corporate industries with discretion on how they interpret and implement environmental sustainability practices. Moreover, cultural and social attitudes towards environmental sustainability are still evolving, with limited discourse relative to sustainability. Environmental sustainability values are not yet adequately institutionalized at the societal and organizational levels [

17].

Environmental sustainability has become a global priority in both research and active efforts. Much of the literature focuses on external drivers, such as regulatory frameworks, policies, and market pressures. These are factors that are often weak in developing and resource-dependent countries such as Libya. In such a context, internal organizational motivation plays a critical role in shaping environmental practices in employees. Despite this, there is a limited body of empirical research exploring the effects of internal motivation factors in developing and fragile institutional environments. This study addresses this gap by carrying out an investigation to examine the influence of internal motivations on corporate environmental management practices in Libyan oil companies. Given the environmental footprint and economic importance of the oil sector in Libya and the growing attention to corporate responsibility, this study is both academically and practically significant for the advancement of environmental sustainability.

3. Methodology

This study uses a quantitative technique to cross-sectionally examine the relationships among EMPs, corporate sustainability motivations, PEB, and environmentally friendly attitudes among employees in the Libyan oil sector. The research design uses inferential statistical analysis to explore the impact of corporate environmental sustainability motivations on the environmental attitude and behavior outcomes of employees.

This study is designed to carry out an individual-level analysis focusing on how employee environmental motivations, attitudes, and behaviors affect environmental management practices. Employees play a critical role in operationalizing environmental sustainability efforts, especially in environmentally intensive industries such as the oil and gas industry. Frontline behaviors, adherence to environmental protocols, and employee engagement directly impact the industry’s environmental outcome.

This study draws on two prominent behavioral theories, the Theory of Planned Behavior by Ajzen [

45] and the Value Belief Norm theory by Stern [

35]. According to these theories, individual behavior is directly influenced by attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. This study is conceptualized based on the underlying influence of environmental motivations in shaping pro-environmental attitude, PEB, and EMPs. This study proposes a model where environmental motivations influence attitudes, behaviors, and EMPs.

Figure 1 illustrates the integrated framework of this study, positioning psychological variables as key drivers of employee interpretation of EMPs within the resource-intensive oil and gas sector.

3.1. Research Case and Sample

This research carries out its investigation in the context of Libyan corporate organizations with an emphasis on Libya’s oil sector. This is chosen as a case study because of the significant environmental challenges faced by Libya and the entire region. Libya faces significant environmental challenges, which include environmental pollution, regulatory gaps, and unsustainable resource management [

56]. These environmental challenges are further exacerbated by the prolonged armed conflicts and civil instability in the country, resulting in economic volatility. Libya’s oil sector represents a significant part of the nation’s economy and is a significant contributor to environmental deterioration. Using this as a case study offers a platform for analyzing the intersection and relationship of corporate environmental sustainability motivations with EMPs, employee environmental attitudes, and PEB. Corporate entities within the oil and gas sector are expected to comply with international environmental sustainability standards and stakeholder expectations, despite operating in a developing country with relatively weak mechanisms of enforcement and limited public environmental awareness and concerns.

This study targets a research population consisting of corporate oil and gas companies’ employees in Libya. The participants of this study were drawn from across multiple organizational hierarchies, ranging from senior executives and mid-level employees to operational staff. This multi-level approach enables a comprehensive understanding of organization-wide findings. This study used a convenience sampling technique to identify and recruit research participants from the target population. The limitations of convenience sampling were carefully considered to ensure the inclusion of participants from different companies, departments, and organizational hierarchical levels.

3.2. Data Collection Instrument

The data collection tool for this study was a structured self-administered questionnaire. The research questionnaire was designed to capture valid and reliable measures of the key variables under investigation in this research. The data collection instrument was designed with survey items from previously validated research scales. Environmental sustainability motivation and environmental management practice scales were adopted from a survey tool designed for corporate environmental management practices by Delmas and Toffel [

57], with totals of 8 and 14 items, respectively. The pro-environmental attitude scale was adopted from the study of Félonneau and Becker [

58], with a total of 27 items. The pro-environmental behavior scale was adopted from the study of Brick et al. [

59] using the recurring pro-environmental behavior scale, with a total of 21 items. All of the scales used for data collection were designed to collect data using a five-point Likert scale.

Questionnaires were distributed electronically and in paper format through the human resource departments of selected oil and gas companies in Libya. Participation was voluntary, and all participants’ confidentiality was assured. To ensure the validity of the data collection instrument, this study used a pilot test involving 15 individuals from the sample population. This pilot test enabled further refinement of item clarity and the layout of the research questionnaire. Minor adjustments were made based on feedback for language simplification and formatting. The primary use of electronic forms enabled built-in restrictions requiring participants to answer all questions; no missing data or responses were recorded. A total of 405 responses were received at the end of the data collection process.

3.3. Methodological Limitations

There are several methodological limitations that are acknowledged in this study. First, the use of a cross-sectional survey design limits the ability of the research to establish causal relationships between the research variables over time. Second, the use of a convenience sampling technique potentially introduces sampling biases and limitations to the generalizability of the findings. Third, the reliance of the primary data collection on self-reported data introduces potential response and social desirability biases, which can potentially impact the accuracy of the research findings. Lastly, the contextual specificity of the study to Libya’s oil sector potentially limits the generalizability and applicability of the research findings.

4. Results

This study successfully collected data from a total of 405 research participants from four major oil and gas companies in Libya. According to the demographic data of the research respondents, the largest sample of participants was from Azzawiya oil refining company, with a total of 140 participants, making up 34.6% of the total participants. The majority of the research participants were male, making up about 75%, with about 25% of the participants being female. The data collected on the participants’ age showed that the majority of the participants were older than 45 years. Participants aged between 36 and 45 years were the minority among the research respondents. Data were collected from a wide categorization of six job designation categories: 24.7% were administrative affairs employees, 2.7% were drilling operations employees, 16.3% were environmental and sustainable development employees, 6.7% were occupational safety and health management employees, 2% were oil employees, and 47.7% were operation engineers, making them the majority of the research respondents.

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the research survey.

4.1. Reliability and Validity

Table 2 shows the results of a reliability analysis that was carried out to ensure the reliability and internal consistency of the research measurement scales before further analysis. The reliability analysis showed Cronbach alpha values of more than 0.7 for all measurement scales, which was the acceptable reliability minimum [

60]. Each scale scored more than 0.8, as shown in

Table 2, which suggests that the items of each measurement scale measured their constructs consistently.

Table 3 shows the results of the normal distribution of the collected data for each scale using skewness and kurtosis. The skewness values range between −0.175 and 0.456, and the kurtosis values range between −0.405 and 0.549. These values are relatively close to zero, which indicates a normal distribution.

4.2. Gender Differences

Table 4 presents a paired

t-test for gender and the environmental constructs. The results of an independent

t-test comparing the mean scores between male and female respondents and each research scale are presented. The results show that there is no statistically significant difference between the male and female respondents relative to each scale of the research. In addition, the means for both male and female respondents are very close. This indicates there is no statistically significant difference in environmental sustainability motivations, pro-environmental attitude, pro-environmental behavior, or EMPs between male and female respondents in this study.

4.3. Age Groups

Table 5 presents the results of an ANOVA for the mean scores of the age group characteristics against the different environmental scales used in this study. A significant difference was found in the pro-environmental attitudes of the respondents relative to their age groups, with a

p-value of 0.001, which is <0.005. This indicates that pro-environmental attitudes differed significantly between employees of different age groups. However, the three remaining constructs (environmental sustainability motivations, behavior, and EMPs) showed no significant differences.

4.4. Job Designations

Table 6 shows the results of an ANOVA for the job designations of respondents and the mean scores of the different scales of this study. Pro-environmental attitude showed a statistically significant difference, with a

p-value of 0.001, which is <0.005. Environmental sustainability motivations, pro-environmental behavior, and EMPs all showed no significant differences. These results indicate that only the pro-environmental attitudes of the research respondents differed according to or depending on their job designations.

4.5. Oil Companies

Table 7 shows the results of an ANOVA for the oil companies at which the respondents worked and the mean scores of the different scales of this study. Pro-environmental attitude showed a statistically significant difference, with a

p-value of 0.002, which is <0.005. No statistically significant difference was found for environmental sustainability motivations, pro-environmental behavior, or EMPs; all three constructs had

p-values > 0.005. This result indicates that only the pro-environmental attitudes of the research respondents differed according to the oil companies in which they worked.

4.6. Correlation Analysis

The table presents the results of a Pearson correlation analysis carried out between all pairs of the four research scales used in this study. A correlation measures the strength of the relationship between two variables. According to the results in

Table 8, environmental sustainability motivations have a significant and positive relationship with pro-environmental attitude, pro-environmental behavior, and EMPs, with

p-values of 0.003, 0.001, and 0.001, respectively. The result also indicates that pro-environmental attitude has a significant and positive correlation with pro-environmental behavior and EMPs, with

p-values of 0.001 and 0.001, respectively. Pro-environmental behavior also showed a significant and positive relationship with EMPs, with a

p-value of 0.003. The correlation analysis between all pairs of research constructs showed significant and positive relationships, except for environmental sustainability motivations and pro-environmental behavior, with a

p-value of 0.006.

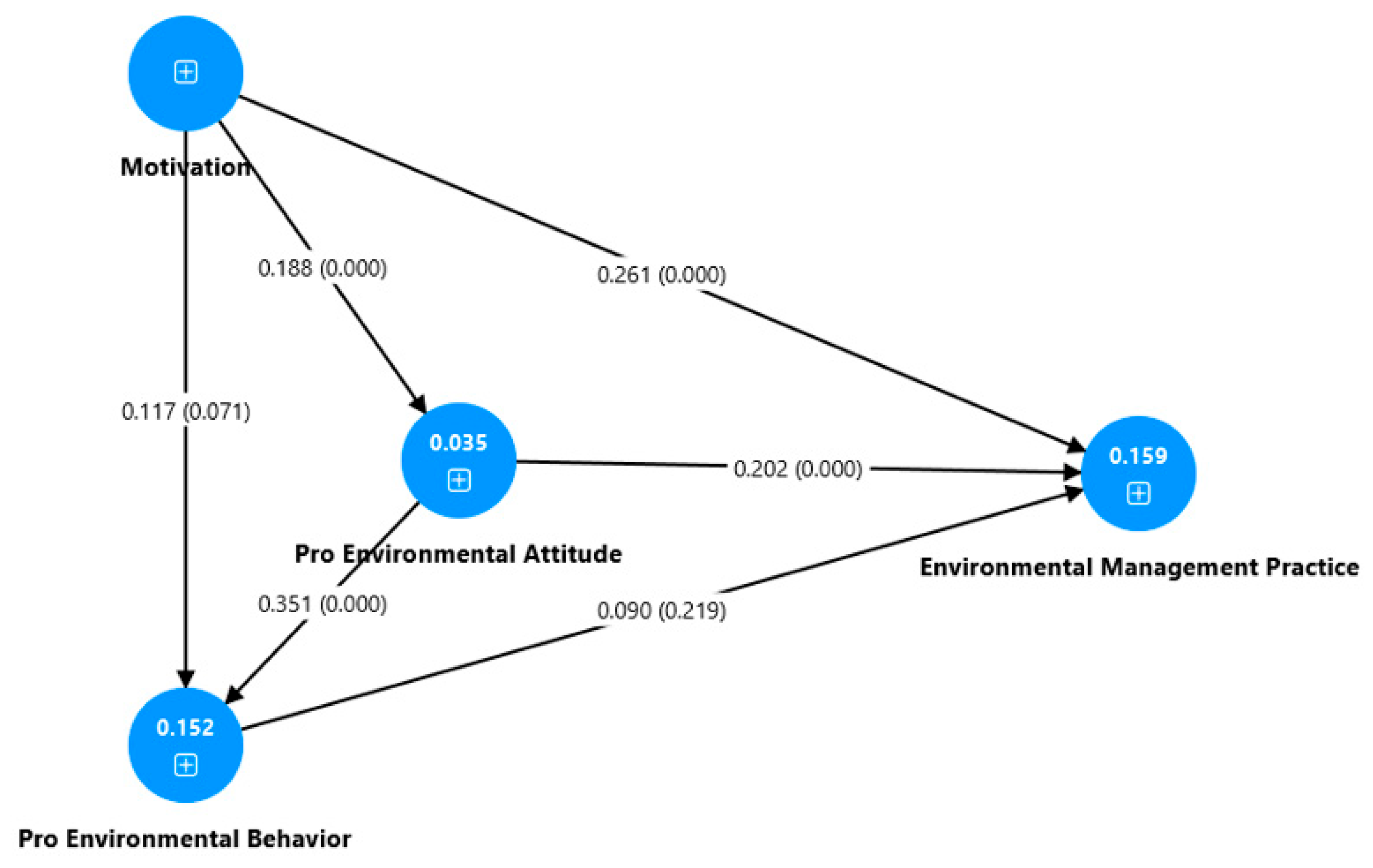

Figure 2 illustrates the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis that was carried out. This analysis is used to analyze the relationships and impacts of the variables of the research model.

Table 9 shows the results of the PLS-SEM analysis, which includes

p-values and T-statistics to determine the significance and direction of the variables’ effects.

The relationship path from environmental motivation to EMPs has a positive path coefficient, with a p-value of 0.00. These results indicate a highly significant and positive effect. Hence, H1 is strongly supported, suggesting that employees’ environmental motivations directly contribute to EMPs in Libya’s oil companies.

The relationship path from pro-environmental attitude to EMP has a positive path coefficient, with a p-value of 0.00. These results indicate a highly significant and positive effect between the two variables. Hence, H2 is strongly supported, suggesting that employees’ pro-environmental attitudes significantly and positively impact EMPs in Libya’s oil companies.

The relationship path from PEB to EMPs has a positive coefficient, but the p-value is greater than the significance value of <0.005 (0.219). These results suggest a positive relationship, but it is not adequately statistically significant to determine the impact. Hence, H3 is not supported, thereby indicating that employees’ PEB does not statistically significantly impact EMPs in Libya’s oil companies.

The relationship path from environmental motivations to pro-environmental attitude has a positive path coefficient, with a p-value of 0.00. These results suggest a positive, highly significant effect between the two variables. Hence, H4 is strongly supported, suggesting that employee environmental motivations significantly and positively impact pro-environmental attitudes in Libya’s oil companies.

The relationship path between environmental motivation and PEB has a positive path coefficient, but with a p-value exceeding the significance threshold of <0.005 (0.071). These results suggest that there is a positive relationship with environmental motivation, but it is not statistically significant. Hence, H5 is not supported, indicating that there is not a positive and significant relationship between employees’ environmental motivation and PEB in Libya’s oil companies.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the influence of corporate environmental sustainability motivations on environmental management practices (EMPs), pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs), and attitudes within Libya’s oil sector. The findings offer valuable insight into how sustainability motivations interact with individual attitudes and organizational practices in a resource-intensive, developing country context.

5.1. Sustainability Motivations and Organizational Practices

Findings show a moderate level of environmental sustainability motivation among employees, which significantly correlates with the implementation of EMPs. This supports Protection Motivation Theory (PMT), which posits that threat appraisal and coping appraisal drive protective behaviors. In this case, employees’ motivations act as a form of coping mechanism, leading to tangible practices like EMPs. Similarly to Delmas and Toffel [

57], this study confirms that higher internal motivation is linked to stronger organizational environmental integration.

However, corporate motivation showed weaker correlations with actual PEBs than with pro-environmental attitudes. This finding aligns with VBN theory, which explains that values and beliefs alone do not guarantee action unless supported by personal norms and perceived behavioral efficacy. Motivation, while necessary, may not be sufficient to activate behavior in the absence of enabling systems, culture, or policies. As reported by Kollmuss and Agyeman [

61], and Budzanowska-Drzewiecka and Tutko [

62], motivation without institutional support or behavioral reinforcement often results in attitude–behavior gaps.

These findings emphasize the importance of mechanisms like green human resource management (GHRM) to bridge the gap between intention and action. GHRM can create enabling environments through training, recognition, and incentives to drive consistent pro-environmental behavior.

5.2. The Role of Pro-Environmental Attitudes

Pro-environmental attitudes emerged as a strong predictor of PEBs, confirming a core assumption of the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB): that behavioral intention is significantly influenced by individual attitudes. Employees who believe they are personally responsible for mitigating environmental degradation were more likely to engage in recurring sustainable behaviors.

Furthermore, pro-environmental attitudes had a positive relationship with the implementation of EMPs, suggesting that individual dispositions can translate into organizational outcomes. This link reflects the Cognitive Behavioral Theory (CBT) lens adopted in this study, where internal cognition and belief systems directly affect observable behavior. Similar patterns have been documented in studies by Deville et al. [

63] and Wyss et al. [

64].

This reinforces the strategic importance of internal employee engagement in environmental programs. Organizations seeking to advance sustainability should invest in cultivating an internal culture of environmental responsibility, supported by education, recognition, and participatory decision-making.

5.3. Organizational Context and Differences

This study revealed no significant differences in environmental constructs across most demographic variables—except when comparing different oil companies. This variation suggests that organizational factors (e.g., leadership commitment, environmental policies, stakeholder influence) play a more substantial role than individual socio-demographic factors. This aligns with Institutional Theory, which recognizes that organizational behavior is shaped by external norms, pressures, and internal governance structures.

The shared levels of awareness and motivation across demographic groups may indicate that awareness campaigns and internal communication strategies are being consistently implemented across the sector. However, the differences observed between oil companies highlight that institutional context and organizational culture are critical determinants of environmental engagement.

Such differences might stem from variations in stakeholder expectations, regulatory pressures, or management priorities. As reported in previous studies [

4,

5], this is particularly relevant in oil-dependent economies, where sustainability practices are often externally driven by compliance rather than intrinsic commitment.

6. Conclusions

This study determines the impacts of corporate environmental sustainability motivations on environmental management practices, environmentally friendly attitudes, and environmentally friendly behaviors in the oil and gas sector in Libya. The findings of this study revealed a statistically significant relationship among corporate environmental sustainability motivations, environmentally friendly attitudes, and environmental management practices. Environmental sustainability motivation did not show a strong influence on pro-environmental behavior. However, pro-environmental attitudes emerged as a significant predictor of pro-environmental behavior. The overall findings of this study generally support the theoretical foundations of the TPB and VBN. The findings of this research also emphasize motivation as a critical factor in fostering environmental attitudes and ensuring adequate environmental management practices.

Given the findings of this study, several actionable recommendations emerge for industry leaders and policymakers. Implementing structured environmental awareness and training programs can strengthen pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors among employees. Organizations should consider adopting internal sustainability benchmarks and performance indicators; these should be made both accessible and transparent to employees at all levels. This will foster corporate cultures of accountability and environmental responsibility. In addition, enhancing the enforcement capacity of existing environmental sustainability regulations and incentivizing corporate sustainability reporting can reinforce both internal and external drivers of sustainability. Encouraging institutional partnerships between academic institutions, government agencies, and oil companies can enhance knowledge transfer in order to ensure environmental sustainability.

Limitations and Future Work

This study was confined to a specific sector, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other industries or regions. This study also focused on internal factors without accounting for external factors, such as regulatory pressure and market dynamics.

Future work in this line of research should explore the roles of organizational leadership style, the regulatory compliance of organizations, perceived behavioral control, and how they influence or impact environmental management practices. Future work should consider exploring external factors to understand the impact that they have on employee sustainability motivations and pro-environmental behavior.