Abstract

This research utilised Value–Belief–Norm theory (VBN) to develop a conceptual framework to test the impact of environmental consciousness on green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude. In addition, this study tested the moderating role of price sensitivity and greenwashing on the indirect impact of environmental consciousness on green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude among consumers in Egypt and Jordan. The study employs a cross-sectional questionnaire using a Likert scale to collect 828 and 776 valid responses from Egypt and Jordan, respectively. The data were analysed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). The results revealed that financial attitude positively mediates the link between environmental consciousness and green behaviour, while price sensitivity and greenwashing significantly moderate the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude in both Egypt and Jordan. The study extends VBN through contextualising its abstract ideas into the research variables and testing it in two developing economies. In addition, it enhances understanding of the barriers to and enablers of green purchasing behaviour and offers actionable recommendations for businesses to improve the transparency and affordability of green products, while guiding policymakers on designing targeted incentives and regulations to foster sustainable consumption.

1. Introduction

The rapid degradation of the global environment, driven by economic growth and population expansion, has placed immense pressure on natural resources and ecosystems. In addition to resource depletion, unsustainable consumption patterns significantly contribute to environmental harm [1]. As awareness of climate change grows, consumers and businesses are increasingly motivated to adopt sustainable practices. A major barrier to genuine sustainability is greenwashing—where companies falsely market products as eco-friendly—leading to consumer mistrust and undermining environmental efforts [2,3,4].

Understanding consumer behaviour in the context of green purchasing is essential for addressing environmental challenges [5]. Green products enable individuals to express their commitment to sustainability through everyday decisions [6]. However, greenwashing continues to block consumer trust, particularly in countries with weak environmental infrastructure, such as Egypt and Jordan [7]. Ineffective waste management, limited recycling and poor regulatory frameworks increase the environmental impact in these regions. This study investigates how greenwashing, distrust, environmental awareness and financial attitudes interact to shape green purchasing behaviour in developing contexts.

To explore these dynamics, the study applies Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) theory [8] in order to provide a theoretical foundation to test how individuals’ consciousness can assign responsibility and act on sustainability values in developing economies [9,10]. This will help extend the theory, as the research tests how financial attitude acts as a mediator and the moderator role of price sensitivity and greenwashing on this indirect relationship. In addition, the dynamic relationship is investigated in two emerging economies (Egypt and Jordan); although the literature on sustainable consumption is growing, it mostly focuses on Western economies, leaving a gap in developing regions [3,11]. In Egypt and Jordan, environmental issues are compounded by underdeveloped infrastructure and weak policy enforcement. By analysing the effects of greenwashing on trust, awareness and purchase decisions, the study contributes context-specific knowledge to the global sustainability discourse.

Raising environmental awareness plays a powerful role in encouraging green consumer behaviour in Egypt and Jordan. This is because the government plays a very important and essential role in prioritizing environmental sustainability and providing financial support [12]. Governments in both countries are pushing towards adapting environmental activities through raising awareness [13]. In Egypt, recent research shows that when people feel confident managing their finances and understand environmental issues, they are more likely to choose eco-friendly products—especially among younger, educated consumers in urban areas [14]. In Jordan, national water conservation campaigns go beyond education; they frame sustainable behaviour as part of being a responsible citizen, linking individual habits to national stability and resource security [15]. These real-world examples highlight how awareness efforts—when grounded in the local context—can shape consumer intentions and reinforce the value of integrating such factors into behavioural models like VBN, particularly in developing countries. Informed by these considerations, the study sets out the following research objectives: (1) to investigate the mediating role of financial attitude in the relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour; (2) to explore the moderating effects of price sensitivity and greenwashing on the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude; and finally, (3) to compare Egypt and Jordan based on demographic characteristics (age, gender and education).

Specifically, this research will help extend the VBN model by exploring the mediating role of financial attitude and the moderating effects of price sensitivity and greenwashing on this indirect relationship, extending the literature with a more grounded model of green behaviour in financially challenged settings [6,14,16,17,18].

In addition, by focusing on Egypt and Jordan, two emerging economies with distinct socio-economic and environmental challenges, the study contributes context-specific insights to the global sustainability discourse, as it focuses on financial feasibility, which is in an important aspect in emerging economies similar to those studied [3,6,10,11,14].

Practically, this will help support the transition toward sustainable consumption and green economic development in emerging markets through creating actionable guidance for businesses to build transparency and for policymakers to counter greenwashing and promote authentic sustainability [19,20]. This could include the expansion of credible eco-labelling systems, and better infrastructure—such as accessible public charging networks—to encourage the adoption of sustainable products like new energy vehicles (NEVs) [21,22]. In addition, it will help promote social welfare through decreasing waste and emissions, which will eventually affect human life positively [23,24].

Furthermore, public awareness campaigns developed in partnership with NGOs, universities, and local organizations have proven effective in improving environmental literacy and encouraging pro-environmental actions, especially among young people [15].

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

VBN theory, first proposed by Stern, Dietz, Abel, Guagnano and Kalof [8], provides a powerful framework for understanding why people choose to act in environmentally responsible ways. VBN theory suggests that behaviour is shaped by a causal chain of psychological variables: personal values (e.g., altruistic, biospheric, or egoistic values) influence environmental beliefs (such as the New Ecological Paradigm), which in turn heighten awareness of consequences and ascription of responsibility for environmental problems. These factors activate personal norms—internalized moral obligations—that ultimately drive individuals to adopt pro-environmental behaviours [8].

This theory has been widely applied in green consumption. For instance, a recent study of tourism and consumer behaviour contexts in Northern Cyprus [25] highlights these fundamental motivations, distinguishing them from purely cognitive mental models. Additionally, Hua and Pang [26] emphasised that rural residents’ green consumption is strongly shaped by income levels and trust in government policies, suggesting that socio-economic factors can amplify or attenuate VBN’s predictive power, while Yue, et al. [27] highlighted the importance of aligning environmental awareness with actionable norms to translate intentions into behaviour. Le, et al. [28] extended VBN to examine how greenwashing undermines consumer trust and weakens pro-environmental norms in Korea and Vietnam. In Malaysia, Alam, et al. [29] applied VBN to investigate how environmental consciousness influences green purchasing intentions, demonstrating the mediating role of personal norms. In Pakistan, Jawed, et al. [30] explored how environmental awareness and ascription of responsibility affect pro-environmental intentions, emphasising the importance of subjective norms alongside VBN variables. Meanwhile, Jiang, et al. [31] in China integrated attitudes as mediators within the VBN model to examine their impact on actual green purchasing behaviour.

Although these studies demonstrate VBN’s versatility, most applications have considered these elements in isolation. Few have combined economic constraints (e.g., financial attitudes and price sensitivity) with trust-related market dynamics (e.g., greenwashing) in a single conceptual framework. This gap is particularly evident in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where socio-economic and institutional contexts differ markedly from the Western settings in which VBN was initially developed. Table 1 shows a comparison between the classical VBN model, its extension in previous studies and its extension in the current study. This comparison highlights the novel integration of financial attitude and contextual moderators.

Table 1.

Comparing VBN model extensions.

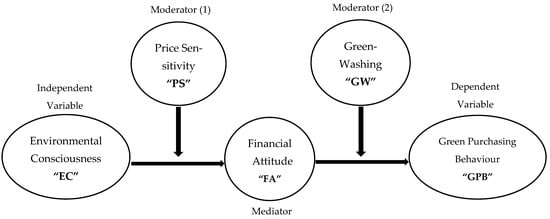

This study addresses this gap by extending VBN to include financial attitude as a mediator, capturing how economic feasibility shapes consumers’ abilities to act on pro-environmental beliefs. It also introduces price sensitivity and greenwashing as moderators to reflect real-world market challenges that may weaken the translation of green intentions into behaviour. Together, these additions create a nuanced, contextually grounded framework for understanding sustainable consumption in emerging economies like Egypt and Jordan. Figure 1 shows the proposed research model.

Figure 1.

Research variables and framework (Source: own research).

Numerous studies have explored the interconnections between environmental consciousness, green purchasing attitude, intention, perceived consumer effectiveness and behaviour. Mishal, Dubey, Gupta and Luo [16] found that environmental consciousness shapes green purchasing attitudes and perceived consumer effectiveness, both of which influence green purchasing behaviour. Similarly, Haj-Salem, et al. [31] investigated how anticipated pride, guilt and environmental consciousness jointly impact green purchasing intentions, highlighting the complex interplay between emotional and cognitive factors. Ahmed, Arshad, Anwar ul Haq and Akram [17] also examined how environmental consciousness, recycling intentions and advertisement credibility affect green purchasing intentions, underscoring the importance of perceived consumer effectiveness and green product knowledge.

2.1. The Mediating Role of Financial Attitude

Environmental consciousness is increasingly recognised as a key driver of sustainability, influencing both consumer awareness and demand for green products [33,34]. As individuals become more aware of environmental issues [35], they are more likely to adopt eco-friendly behaviours, including purchasing green products [36,37]. This growing sense of responsibility motivates consumers to align their actions with environmental values, such as choosing green alternatives over conventional options [38].

Environmental values—a core element of environmental consciousness—exert a stronger influence on green purchasing intentions than general concern or knowledge. Consumers who adopt these values are more likely to act on them through their purchasing choices [39]. Additionally, subjective norms, attitudes and perceived behavioural control significantly contribute to shaping green purchasing intentions and reinforcing behaviour [40].

However, a growing body of research highlights that environmental awareness alone may not be sufficient to translate pro-environmental intentions into action, particularly in resource-constrained contexts. Financial attitudes—such as the willingness to pay a premium for eco-friendly products or to adjust household budgets for sustainable alternatives—play a critical mediating role in this relationship. For instance, Gomes, et al. [41] investigate the underlying determinants shaping Portuguese Generation Z’s demand for green products and examines how these factors influence their willingness to pay a premium for sustainable alternatives. Similarly, Kim and Lee [42] reported that financial attitudes act as a key determinant of whether awareness leads to sustainable consumption, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

This mediating effect is especially relevant in developing economies where eco-friendly products are often perceived as expensive or inaccessible. A study by Yue, Sheng, She and Xu [27] indicates that without a supportive financial disposition, even individuals with strong environmental values may fail to act sustainably. Ali, Barky and Barakat [14] further demonstrate that in the Egyptian context, environmental knowledge and financial self-efficacy significantly predict green purchasing intentions, with demographic variables such as age and gender moderating these relationships.

These findings suggest that financial attitudes serve as a crucial bridge between environmental consciousness and sustainable consumer behaviour, enabling or constraining action depending on economic feasibility. Thus, based upon the previous discussion, the first hypothesis is developed as follows:

H1.

Financial attitude mediates the relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour.

2.2. Moderating Effects of Price Sensitivity

Price sensitivity is a key moderator in the relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour [43]. While heightened environmental awareness often motivates consumers to choose eco-friendly products, this intention does not always translate into action when the perceived cost of such products is high. For price-sensitive consumers, financial considerations can override pro-environmental values, leading to reduced willingness to pay for sustainable alternatives [44,45]. This aligns with prior findings that the relatively higher price of green products often acts as a psychological and financial barrier, weakening the influence of environmental consciousness on actual purchasing decisions when price sensitivity is elevated [11,18].

Recognising this moderating effect is critical for businesses and policymakers seeking to promote green consumption [43]. When price sensitivity is low, consumers with strong environmental consciousness and favourable financial attitudes are more inclined to purchase green products. However, in contexts such as Egypt and Jordan—where economic pressures and limited purchasing power amplify price sensitivity—strategies to mitigate cost barriers become particularly relevant.

Previous studies have highlighted practical interventions to address this issue. For example, implementing financial incentives such as subsidies, discounts, or value-added features can help offset price concerns and encourage sustainable purchasing [46]. Additionally, consumer education campaigns that highlight the long-term economic benefits of green products—such as energy efficiency, durability, and reduced operational costs—have been shown to reduce perceived cost barriers and increase willingness to pay for sustainability [46,47]. These approaches may be particularly effective in developing economies, where upfront costs often overshadow the potential for long-term savings. Accordingly, the following second hypothesis could be proposed:

H2.

Price sensitivity moderates the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude.

2.3. Moderating Effects of Greenwashing

Greenwashing—the act of misleading consumers about a product’s or company’s environmental performance—undermines consumer trust and brand credibility [10,48]. Despite rising interest in eco-friendly products, many consumers struggle to differentiate between genuine and deceptive environmental claims. This uncertainty weakens trust in green labels and lowers the likelihood of purchase, even among environmentally conscious consumers [3,49].

Alarmingly, greenwashing is evident even among firms claiming adherence to ESG (Environmental, Social and Governance) standards and sustainability reporting. Some companies fail to disclose essential details about product origins, production practices or supply chain ethics. This highlights the need for stronger supply chain transparency and the corporate sustainability due diligence directive (CS3D). Many products sold in Western markets but produced in developing countries lack adequate disclosure about sourcing, labour conditions or human rights compliance—whether due to intentional deception or poor documentation. This complexity increases consumer uncertainty and complicates sustainable decision-making.

Greenwashing, where companies present a misleading image of environmental responsibility, has become increasingly prevalent in Egypt and Jordan, undermining genuine sustainability efforts and eroding consumer trust [50]. For instance, in Egypt’s hospitality sector, many five-star hotels market themselves as eco-friendly but limit their sustainability efforts to surface-level actions like signage and slogans, without implementing meaningful operational changes [50]. Similarly, in Jordan, greenwashing is often linked to international development projects that use “green” branding to mask socially or environmentally disruptive impacts, contributing to public doubt about the authenticity of sustainability narratives [51]. These examples illustrate the importance of examining how greenwashing moderates consumer trust in green purchasing decisions.

The interplay between financial attitudes, greenwashing and green behaviour is especially nuanced. Financially conscious consumers who prioritize responsibility tend to scrutinise environmental claims [52]. When exposed to greenwashing, their trust diminishes, reducing both purchase intent and brand confidence. This underscores the need for companies to ensure transparency and integrity in their sustainability communications to retain trust among environmentally and financially aware consumers [10]. This aligns with Eid, et al. [53,54], who found that transparency—like our greenwashing construct—critically alters the strength of awareness-driven intentions in airport environmental behaviours, reinforcing the importance of external credibility, as per Ahmed, Arshad, Anwar ul Haq and Akram [17], and Haj-Salem, Ishaq and Raza [31]. Accordingly, the following third hypothesis could be proposed:

H3.

Greenwashing moderates the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude.

3. Materials and Methods

This study adopted a quantitative research design to examine the factors influencing green purchasing behaviour in two developing economies: Egypt and Jordan. The conceptual framework, grounded in the VBN theory and extended to include economic and trust-related variables, was tested using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). Specifically, Covariance-Based SEM (CB-SEM) was employed, as it is particularly well-suited for theory testing. CB-SEM provides robust goodness-of-fit indices and allows for simultaneous evaluation of measurement and structural models, making it ideal for validating the hypothesised moderated mediation framework [55,56]. In addition is more suitable when sample size is large [57].

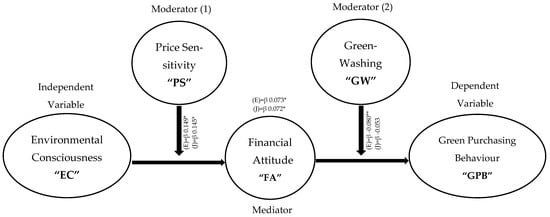

The conceptual framework illustrated below in Figure 2 was developed based on the VBN theory, extended to incorporate financial and trust-related factors relevant to emerging markets. The model was designed to operationalise the key research objectives mentioned in the introduction. Data were analysed using Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) 24.0 and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 26.0. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the validity and reliability of the measurement model. CB-SEM was applied to test the hypothesised relationships and evaluate model fit. Multi-group SEM analysis was performed to compare the dynamics across Egypt and Jordan.

Figure 2.

Results of the hypothesis testing of Egypt (E) and Jordan (J) using SEM, showing the direct and indirect effect. (Source: own research). Notes: * indicates significance at the 1% level, ** indicates significance at the 5% level.

The methodological approach was designed to align closely with the study’s objectives. CB-SEM bootstrapping techniques were used to test the mediating role of financial attitude in the relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour. To fulfil the objective of analysing the moderating effects of price sensitivity and greenwashing on the indirect relationships, we applied the technique and the approach proposed by Preacher, et al. [58], ensuring robust estimates of indirect and interaction effects. This technique and approach have been adapted by similar studies, e.g., [24,53,59].

3.1. Study Context

In the context of the socio-economic and environmental dynamics of Egypt and Jordan—two MENA nations dealing with serious environmental and economic issues—this study examines green consumer purchasing behaviour. In both countries, rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and population growth have put stress on natural resources, resulting in deforestation, air and water pollution, and increased vulnerability to climate change [13]. As a result, the Ministry of Environment in Jordan has made cutting industrial emissions and developing green technology a top priority [60,61]. In Egypt, the government is increasingly investing in sustainable industrial clusters as part of its green transition strategy. For example, the Borg El Arab cluster in Alexandria serves as a hub for eco-friendly industries and green supply chains, integrating renewable energy, waste management and resource efficiency practices. Saad and Barakat [62], Ali, et al. [63], Ali and Barakat [64], Barakat, et al. [65], Dabees, et al. [66], Barakat, et al. [67], Barakat, et al. [68] and Barakat [69] highlight that such initiatives are critical for developing the dynamic capabilities that will drive sustainable initiatives in Egypt, supporting the transition towards greener industrial ecosystems.

Economic constraints also influence consumer behaviour in both countries but take many forms. In Jordan, renewable energy initiatives such as solar energy projects have advanced the transition towards green industries and job creation, fostering a supportive ecosystem for sustainable consumption. In Egypt, however, high poverty rates and currency depreciation have exacerbated price sensitivity, making consumers more reluctant to purchase green products, which are often perceived as premium-priced [70].

Another shared challenge is greenwashing, which reduces consumer trust in eco-friendly claims. In Jordan, green branding is sometimes associated with international development projects whose outcomes have been questioned in terms of social and environmental integrity [46]. Similarly, in Egypt, surface-level “green” initiatives by firms—particularly in sectors like hospitality—often lack meaningful operational changes, eroding consumer confidence in sustainability narratives [71].

Given these dynamics, Jordan and Egypt provide a highly relevant context for examining green purchasing behaviour in emerging markets. Both nations are actively pursuing environmental transitions through national plans (e.g., Jordan’s National Green Growth Plan (NGGP) [60] and Egypt’s Green Energy Corridor [70]), yet socio-economic constraints, institutional gaps and trust issues remain significant barriers. This study seeks to address these gaps by investigating how environmental consciousness, financial attitudes, price sensitivity and greenwashing jointly shape consumer behaviour. The findings offer context-specific insights for policymakers, businesses and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) seeking to overcome affordability, accessibility and credibility challenges to foster authentic sustainable consumption in the MENA region.

3.2. Sample and Procedures

A snowball sampling technique was used to collect data for the pilot and main studies in Egypt and Jordan. Due to the absence of formal databases of environmentally conscious consumers, initial participants were screened for prior interest in green products and expanded through their networks. The sampling focused on major urban centres—Cairo, Alexandria and Giza in Egypt, and Amman, Zarqa and Irbid in Jordan—where awareness of sustainability issues and access to eco-friendly products are higher. They are major urban centres with higher education levels, better access to information and greater exposure to environmental campaigns and green products. Prior studies, e.g., [14,23,72] have similarly focused on these cities to capture consumer trends in sustainability. In contrast, rural areas often face literacy gaps, limited green product availability and limited environmental awareness, making them less suitable for assessing the proposed framework [73]. Concentrating on urban areas ensures the study targets populations where green purchasing behaviours are observable.

The questionnaire’s cover page defined “green products” precisely and listed the main characteristics examined in this study to guarantee participant relevance. In addition, participants were asked to refer other individuals who were involved in sustainable consumption to make sure that participants had an interest in green products. In order to limit the bias associated with the snowball technique, several clusters of participants were started.

Data were collected over a period of approximately four months, starting on 17 November 2024. Sample size adequacy was carefully considered to ensure robustness for SEM. Previous studies recommend a sample size between 100 and 200 observations as optimal for SEM [74]. Nicolaou and Masoner [75] suggest a rule of 5–10 observations per measurement item, with Kline [76] emphasizing a minimum of 200 observations to enhance accuracy. Based on these guidelines, this study targeted a pilot sample of 254 and 227 respondents in Egypt and Jordan, respectively, and a main study sample of 828 and 776 respondents in Egypt and Jordan, respectively, satisfying the rule of 10 (10 × 20 measurement items). This approach exceeds the average sample size used in comparable sustainability and consumer behaviour studies [77,78], ensuring sufficient statistical power for SEM analysis.

A pre-test was conducted to evaluate the clarity, structure, completeness and appropriateness of the measurement items. Table 2 presents the demographic and sample characteristics for the main study.

Table 2.

Sample Characteristics.

The data demonstrate a balanced representation of gender, age groups and education levels, ensuring a comprehensive analysis of green purchasing behaviour.

3.3. Research Instrument

This study investigates the influence of environmental consciousness (EC) as an antecedent of green purchase behaviour (GPB), while examining the mediating role of financial attitude (FA) and the moderating effects of price sensitivity (PS) and greenwashing [16]. To enhance validity and reliability, measurement scales were adapted from previous studies. Questionnaire items were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7), which supports measurement precision and reliability [79].

The study employs a consumer-level sample to test the conceptual framework and hypotheses. A cross-sectional survey was conducted to collect quantitative data on EC, FA, PS, GW and GPB. The questionnaire includes six sections: five covering the study variables and a final section on demographic information, such as age, income/expenditure, marital status, education level and nationality. EC and GW were each measured using 5 items, FA and PS with 3 items each and GPB—the dependent variable—with 4 items.

All questionnaire items were derived from validated scales in prior research, with minor modifications to ensure contextual relevance and clarity. Detailed information on the constructs and corresponding items is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Research Constructs’ Implementation and Measurements.

3.4. Pre-Test and Pilot Study

The research variables identified through the literature review underwent a pre-test with experts—two practitioners and two academics from each country—specialised in green product supply chains, to ensure face validity [80]. All experts held senior roles with over ten years of experience. Participants completed the questionnaire and provided feedback on its clarity and construct accuracy. Given the bilingual nature of the study, the survey was distributed in English and Arabic, with a back-translation process used to ensure linguistic accuracy and conceptual consistency.

The pre-test was followed by pilot studies in Egypt and Jordan. During the pilot study in Egypt, 280 surveys were distributed, yielding 262 responses, with 254 valid responses, after excluding 8 incomplete ones—resulting in a 90.71% response rate. In Jordan, 250 surveys produced 231 responses, with 227 valid responses, after excluding 4 incomplete ones, resulting in a 90.80% response rate. These high response rates reflect strong participant engagement and provide a sound basis for further analysis. Table 4 shows the summary of response rates for the pilot study and the main study.

Table 4.

Study Response Rates.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results demonstrated strong model fit. In Egypt, the chi-square value was 300.004 (degrees of freedom (df) = 160, p = 0.000), with a chi-square to degrees of freedom (CMIN/DF) ratio of 1.875. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.059 (90% confidence interval (CI): 0.048–0.069), the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) was 0.897, Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) 0.865, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) 0.954, Normed Fit Index (NFI) 0.907 and Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) 0.945—all indicating excellent fit [76,81,82,83].

Similarly, the Jordan CFA showed strong fit: chi-square = 285.753 (df = 160, p = 0.000), CMIN/DF = 1.786, RMSEA = 0.059 (90% CI: 0.048–0.070), GFI = 0.890, AGFI = 0.856, CFI = 0.950, NFI = 0.893 and TLI = 0.940. Though GFI was slightly below 0.90, all indices fell within acceptable thresholds [83].

Overall, the consistent model fit across both countries—CMIN/DF < 3, RMSEA ≈ 0.059 and CFI > 0.950—supports the reliability and validity of the constructs. These results affirm the robustness of the measurement model and its applicability in cross-cultural contexts [55,84].

The pilot study conducted in Egypt and Jordan demonstrated strong construct validity and reliability, with most factor loadings exceeding the 0.70 threshold, indicating robust associations between observed variables and latent constructs [85]. In both countries, the Environmental Consciousness construct exhibited loadings ranging from 0.73 to 0.88, reflecting strong convergent validity [76].

For Financial Attitude, factor loadings ranged from 0.76 to 0.87, confirming the reliability and validity of this construct in both contexts [56]. Similarly, Green Purchasing Behaviour items showed loadings between 0.74 and 0.84, further supporting their construct validity in Egypt and Jordan [84]. Additionally, the Price Sensitivity and Greenwashing constructs demonstrated loadings between 0.72 and 0.84, affirming their reliability across both samples.

The consistency of these results across both pilot studies indicates that the measurement instruments are valid and reliable for assessing the key constructs in the context of green purchasing behaviour in Egypt and Jordan.

The reliability and validity of the constructs used in the pilot studies conducted in Egypt and Jordan were strictly assessed to ensure the robustness of the measurement model. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed using AMOS to compute factor loadings, composite reliability [74] and average variance extracted (AVE), which together measure the instrument’s reliability and validity [55]. The CFA results in Table 5 confirm construct validity by demonstrating the strength of relationships between observed items and their respective latent constructs. Factor loadings of 0.70 or higher provide strong evidence of convergent validity, while values between 0.50 and 0.70 may be considered acceptable in exploratory research contexts [86].

Table 5.

Pilot study reliability and validity.

Following the presentation of the pilot study results, specific item-level loadings further illustrate the measurement quality and contextual nuances observed across both countries:

- Price Sensitivity (PS) showed strong agreement, with PS1 in Jordan loading at 0.932 and PS3 in Egypt at 0.951;

- Greenwashing demonstrated stronger loadings in Egypt, particularly GW1 (0.914) when compared to Jordan’s (0.790);

- For Financial Attitude (FA), Egypt’s FA1 reached 0.931, slightly higher than Jordan’s FA1 (0.906), while Jordan displayed more consistent item loadings, such as FA3;

- Green Purchasing Behaviour items loaded highly in both contexts, with Jordan’s GPB3 achieving a loading of 0.873;

- Environmental Consciousness was comparable between countries, with Egypt’s EC4 at 0.866 and Jordan’s EC5 at 0.840.

These minor variations suggest possible cultural or contextual influences on how respondents perceive specific items. Feedback collected during the pre-test phase contributed to refining item wording, enhancing clarity and ensuring that the measurement instrument remained reliable and relevant across both cultural settings.

Despite the fact that the endogeneity issue cannot be totally resolved [87], a Ceteris Paribus assumption has been applied, considering that other demographic factors (such as marital status [88] and occupation [89]) that might influence green purchasing were held constant. Prior research highlights that marital status shapes consumer priorities and long-term sustainability considerations [88], while occupation influences financial stability and exposure to eco-friendly practices [89]. By including age, gender and education as control variables [90,91], we aimed to reduce the risk of omitted variable bias and strengthen the robustness of our model.

Additionally, the SEM’s output showed that the framework had strong theoretical and empirical foundations, and the empirical data demonstrated that the study’s constructs were significantly connected and error-free [23,24]. Finally, statistical methods cannot identify variables that have been omitted [92].

It is also important to mention that multicollinearity was tested through examining the correlation coefficient between the variables to make sure it did not exceed 0.65 [93]. The results of our study confirmed that the dataset did not have the problem of multicollinearity, as correlation coefficients between constructs were less than 0.65; see Table 6 for square root of AVE and correlations between constructs in the main study.

Table 6.

Main study reliability and validity.

3.5. Main Study

The details of the main study response rates are shown in Table 3, above. For the main study of Egypt, the same steps as the pilot study were followed: 922 questionnaires were distributed to the targeted sample. The authors collected 865 responses, and there were 37 incomplete questionnaires. The number of valid questionnaires was 828. This means that the response rate is 89.80%.

For Jordan’s main study, the same steps were followed: 847 questionnaires were distributed to the targeted sample. The authors collected 820 responses, and there were 44 incomplete questionnaires. The number of valid questionnaires was 776. This means that the response rate is 91.62%.

The SEM results for the Egypt and Jordan main studies indicate strong model fit, confirming the adequacy of the proposed structural models. For Egypt’s main study, the chi-square (CMIN) was 969.452 with 242 degrees of freedom (p-value = 0.000), and the CMIN/DF ratio was 4.006, reflecting a moderate fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.060, with a 90% confidence interval of 0.056–0.064, meeting the recommended threshold of ≤0.08. Additional fit indices also supported the model’s adequacy, with a Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) of 0.916, an Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) of 0.887 and a Comparative Fit Index (CFI) of 0.933, all exceeding the recommended cutoff values of 0.90. The Normed Fit Index (NFI) was 0.913, and the Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) was 0.737. Hoelter’s Critical N was 239 (at p = 0.05), further confirming the model’s suitability for the sample size.

Similarly, Jordan’s main study demonstrated strong model fit, with a chi-square (CMIN) of 924.891 and 242 degrees of freedom (p-value = 0.000). The CMIN/DF ratio was slightly lower at 3.822, indicating a good fit. The RMSEA for Jordan’s study was also 0.060, with a 90% confidence interval of 0.056–0.064, mirroring the Egypt results and meeting the recommended threshold. The GFI was 0.915, the AGFI was 0.886 and the CFI was 0.932, all indicative of excellent fit. Additional indices, such as the NFI (0.911) and PNFI (0.735), supported the model’s adequacy, while Hoelter’s Critical N of 235 confirmed the adequacy of the sample size for testing the structural model.

The empirical findings for both Egypt and Jordan indicate a satisfactory model fit, with all primary goodness-of-fit indices falling within the recommended thresholds. This confirms the adequacy of the structural model and contributes empirical support to the hypothesised relationships between the study constructs. These results stress the robustness and generalisability of the proposed model across culturally distinct contexts.

Moreover, the measurement model demonstrated satisfactory levels of reliability and validity. As shown in Table 6, all constructs exhibited adequate internal consistency and convergent validity, with item loadings and composite reliability values meeting established benchmarks. Discriminant validity was evaluated using a criterion which involves comparing the square root of the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct with its inter-construct correlations. The results, presented in Table 7, indicate that all constructs are empirically distinct, thereby affirming the discriminant validity and overall adequacy of the measurement model [94].

Table 7.

Square root of AVE and correlations between constructs in main study.

3.5.1. Non-Response Bias and Common Method Bias

To assess non-response bias, the study compared early and late respondents, using Levene’s test for equality of variances. The results revealed a non-significant p-value, indicating no substantial difference in variance between the two groups and suggesting that non-response bias was not a concern [95].

To address common method bias, Harman’s single-factor test was conducted by loading all questionnaire items into a single factor. The analysis showed that no single factor accounted for more than 50% of the total variance, confirming that common method variance was not a significant issue [96]. These tests collectively support the robustness of the study’s findings and minimise concerns related to the data collection method.

3.5.2. Hypothesis Testing

The results of the SEM analysis illustrate the relationships between the constructs and the hypothesised direct and indirect effects as shown in Figure 2 for Egypt and Jordan. The mediating role of Financial Attitude (FA) was assessed using a two-step approach that involved calculating path coefficients for both direct and indirect effects. The indirect effect of Price Sensitivity (PS) on Green Purchasing Behaviour (GPB) through Financial Attitude was found to be significant, suggesting that shifts in financial attitudes can influence purchasing behaviours when price considerations are prominent. This aligns with findings in prior studies that highlight the influence of financial perceptions on consumer behaviour [36,97,98,99].

H1.

Financial attitude mediates the relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour.

The analysis confirmed that environmental consciousness significantly influences financial attitude in both Jordan (β = −0.341, p = 0.002, lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.424 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.263) and Egypt (β = −0.342, p = 0.005, lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.421 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.255). Similarly, financial attitude has a significant negative impact on green purchasing behaviour in Jordan (β = −0.284, p = 0.002, lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.367 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.217) and Egypt (β = −0.288, p = 0.002, lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.372 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.216). The mediation effect was significant in both countries (Jordan: indirect effect via FA β = 0.072, p = 0.001, lower bound of a confidence interval = 0.050 and upper bound of a confidence interval = 0.105; Egypt: indirect effect via FA β = 0.073, p = 0.001, lower bound of a confidence interval = 0.051 and upper bound of a confidence interval = 0.107), indicating that financial attitude mediates the relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour. Individuals with higher environmental awareness might adopt more critical or cautious financial attitudes [100]. This finding is consistent with the literature, which often associates environmental awareness with heightened inspection and judgement in financial decision-making [101].

H2.

Price sensitivity moderates the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude.

Price sensitivity significantly moderated the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour via financial attitude in both contexts. In Jordan, the moderated mediation effect illustrated β = −0.052 (p = 0.001), lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.090 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.031; Egypt: illustrated β = −0.057 (p = 0.002), lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.091 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.031. This suggests that price considerations shape financial attitudes, subsequently affecting purchasing decisions [102]. The mediating role of financial attitudes in consumer behaviour has been well-documented in similar contexts [103].

H3.

Greenwashing moderates the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour through financial attitude.

Greenwashing also significantly moderated the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness, financial attitude and green purchasing behaviour. The moderated mediation effect of greenwashing illustrated β = −0.036 (p = 0.027), lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.064 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.005 in Jordan and β = −0.039 (p = 0.010), lower bound of a confidence interval = −0.072 and upper bound of a confidence interval = −0.006 in Egypt, indicating that greenwashing weakens the indirect pathway in both countries.

Consumers in Egypt appear more sensitive to deceptive environmental claims, reducing their willingness to buy eco-friendly products in such cases. A recent SEM study among Egyptian consumers confirmed that greenwashing significantly undermines green purchase intentions by eroding trust and perceived authenticity of green branding [50].

These findings highlight important contextual differences between Egypt and Jordan. Consumer sensitivity to greenwashing can vary based on cultural, reputational and market-level trust factors [4,104]. While greenwashing significantly affects trust in both countries, its direct impact on green purchasing behaviour emerges only in the Egyptian sample.

In both contexts, greenwashing significantly moderates the indirect relationship between environmental consciousness and green purchasing behaviour—emphasising the importance of transparent and credible sustainability claims in fostering consumer trust and sustainable consumption. Additionally, financial attitude was found to moderate the effect of greenwashing, revealing complex consumer responses shaped by economic scrutiny and trust vulnerabilities across cultural contexts. Table 8 illustrates a summary of the hypothesis testing.

Table 8.

Summary of hypothesis testing results.

3.5.3. Comparative Analysis

This section illustrates the comparative analysis conducted using an independent sample t-test (SPSS) and multigroup analysis (AMOS). First an independent sample t-test was conducted to compare responses for the variables in Table 9. Then, an independent sample t-test was conducted for the demographics of age, gender and educational level, as shown in Table 10.

Table 9.

Results of independent sample t-test.

Table 10.

Demographics considered in independent sample t-test.

In order to perform more in-depth comparative analysis, a multi-group analysis was conducted to test the impact of demographic characteristics on the dependent variable GPB, with results shown in Table 11.

Table 11.

Multi-group analysis for demographics characteristics.

It can be observed from Table 9, Table 10 and Table 11 that there is no significant difference between the demographic groups in both countries which justify the similarities in the output. This finding is related to the third objective, comparing the demographic characteristics of Egypt and Jordan.

This result is supported by the output of previous studies; for example, Aldegheishem [105] indicated that energy consumption and its impact on CO2 emission were similar in both Egypt and Jordan. Meanwhile, Hammoudi Halat, et al. [106]; Helmy and Abdou [107]; and Bekhit, Rafei, Elnaggar, Al-Sakkaf, Seif, Samardali, Alabead, Sanosi, Abdou, Elbanna and Khalil [21] concluded that consumer behaviour and culture are similar to an extent in both Egypt and Jordan.

Even though Egypt has an abundance of water [108] compared to Jordan [15], both countries are facing similar challenges, as the Egyptian Nile is contaminated by pollution and requires strategic action. In addition, both countries have very similar sustainability strategies such as green hydrogen production and infrastructure using water sources [108]. Furthermore, both countries are facing the same political and security issues [109].

4. Discussion of the Research Findings

This study set out to explore the factors that shape green purchasing behaviour in developing countries, focusing on Egypt and Jordan. By aligning the findings with the research objectives, the study provides a nuanced understanding of how cognitive, economic and trust-related factors interact to influence sustainable consumption in these emerging markets.

The findings of this study provide important insights into the drivers and barriers of green purchasing behaviour in developing countries, specifically Egypt and Jordan. By employing the VBN theory [8], this research presents a comprehensive framework illustrating how cognitive, moral and contextual factors interact to shape sustainable consumer decisions. This offers a more nuanced perspective compared to research conducted in developed contexts, where economic and institutional constraints are less pronounced.

It was found that, regarding the first objective, the mediating role of financial attitude emerged as a significant mediator, highlighting that pro-environmental values alone are insufficient without economic feasibility. The findings highlight the mediating role of financial attitude, supporting prior research that underscores economic feasibility as a critical bridge between environmental intentions and actions [28,31]. This aligns with Elbarky, Elgamal, Hamdi and Barakat [6], who emphasized financial attitudes as pivotal in transforming awareness into behaviour.

Regarding the second objective, the moderating effects of price sensitivity and greenwashing were validated, demonstrating how market and trust-related constraints weaken the relationship between environmental consciousness and actual green purchases.

Price sensitivity significantly weakens the positive effect of environmental consciousness on green purchasing behaviour. This finding is consistent with Bhutto, Tariq, Azhar, Ahmed, Khuwaja and Han [18] and Lavuri [11], who identified cost as a major deterrent in low-income contexts. Barbu, Catană, Deselnicu, Cioca and Ioanid [47] suggested that raising long-term cost awareness and implementing consumer education campaigns could help reduce price-related barriers and increase willingness to pay for sustainability.

Greenwashing emerged as a particularly potent inhibitor of green purchasing behaviour in both countries. The findings confirm that greenwashing significantly erodes consumer trust, discouraging environmentally conscious purchasing. This supports the arguments of Nguyen, Yang, Nguyen, Johnson and Cao [3] and Hameed, Hyder, Imran and Shafiq [10], and aligns with Ayoub and Awad [50], who documented widespread misleading environmental marketing in Egypt and Jordan. For example, in Egypt’s hospitality industry, “eco-friendly” branding often amounts to surface-level initiatives such as signage, without meaningful operational changes [110]. Moreover, some companies deliberately underreport actual sustainability actions to avoid scrutiny or accusations of greenwashing—a phenomenon known as greenhushing, observed particularly in Egypt’s tourism sector, for example by Font, et al. [111]. In Jordan, international development projects sometimes use “green” branding to mask socially or environmentally disruptive impacts, further contributing to public scepticism about sustainability narratives [51]. Fernandez [112] highlights how companies in both countries rely on vague, self-reported indicators without third-party verification, exacerbating consumer distrust.

The third objective related to the comparative analysis of both countries, though economic constraints and institutional gaps influence this relationship’s strength. In Egypt and Jordan, green consumer behaviour reflects both significant constraints and emerging opportunities. Economically, both nations face high poverty rates and inflation—particularly acute in Egypt—limiting consumers’ abilities to purchase eco-friendly products. This reinforces the perception that sustainable consumption is a luxury rather than a necessity.

These insights underscore the urgent need for stricter marketing regulations, verified ESG reporting, and greater supply chain transparency, especially for ESG-aligned firms. Such measures are essential to counteract global value chain opacity, which often misleads consumers about the actual environmental footprint of their purchases.

Structural and institutional challenges, including inadequate recycling infrastructure and limited availability of green products, further constrain green consumption. These findings resonate with Abdel-Shafy and Mansour [7], who emphasized the role of infrastructure in driving or impeding environmental progress. Nonetheless, political initiatives such as Egypt’s COP27 and “Decent Life Initiative (Hayah Karima)” [70] and Jordan’s National Green Growth Plan [60] signal growing political commitment to sustainability. While these initiatives may not yet fully resolve consumer trust or affordability issues, they provide a roadmap for future progress.

5. Conclusions

This study provides valuable insights into the factors influencing green purchasing behaviour in Egypt and Jordan, highlighting the mediating role of financial attitude and the moderating effects of price sensitivity and greenwashing. The findings reveal that environmental consciousness alone does not guarantee sustainable consumer behaviour; instead, economic feasibility and trust-related market dynamics play crucial roles in shaping purchasing decisions. By demonstrating how financial attitudes facilitate the translation of pro-environmental values into action, and how price sensitivity and greenwashing can weaken this relationship, the study offers a more nuanced understanding of consumer behaviour in developing contexts.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

This study advances the theoretical understanding of sustainable consumer behaviour by extending the VBN framework to incorporate economic and trust-related factors that are particularly salient in developing economies. By integrating financial attitude as a mediator, the research highlights how economic feasibility shapes the translation of pro-environmental intentions into actual behaviour. This extension addresses a key limitation of prior VBN applications, where financial constraints were often overlooked despite their critical role in low- and middle-income contexts like Egypt and Jordan [6,36].

This study advances the existing literature by applying a moderated mediation framework based on VBN theory in the context of developing countries. While previous studies (e.g., Mishal, Dubey, Gupta and Luo [16]; Ahmed, Arshad, Anwar ul Haq and Akram [17]) examined perceived efficacy and trust, they did not incorporate financial attitude as a mediator or assess the moderating roles of price sensitivity and greenwashing. This research fills this gap by demonstrating how financial feasibility and perceived corporate honesty shape the translation of environmental values into behaviour. Similarly, Bhutto, Tariq, Azhar, Ahmed, Khuwaja and Han [18] and Lavuri [11] addressed pricing impacts but did not explore indirect effects mediated through financial attitudes.

Moral norms and personal values can foster environmental responsibility; however, these beliefs frequently encounter practical challenges, such as elevated costs and inconsistent marketing claims, which undermine their influence on behaviour [11,18].

Furthermore, the inclusion of greenwashing as a moderating variable provides new insights into how trust-related market dynamics can weaken the established value–belief–norm pathway. This builds on prior research by showing how perceived dishonesty in environmental claims erodes consumer trust and inhibits sustainable behaviour, even among environmentally conscious individuals [3,10,48].

By employing a moderated mediation design, this study empirically validates the interplay of cognitive, moral, economic and external attribution factors in two underexplored developing country contexts. This approach provides a contextually grounded and flexible theoretical framework that moves beyond static assumptions of single-theory models. It underscores the need for behavioural models to account for the institutional realities and cultural nuances that shape consumer priorities in emerging markets [99,113]. Together, these contributions fill important gaps in the literature and offer a systematic foundation for future research to explore similar dynamics in other regions where financial constraints and trust deficits remain significant barriers to sustainable consumption.

5.2. Practical Contributions

This study makes relevant, context-specific contributions to promoting sustainable consumption in Egypt and Jordan. Managerially, businesses must focus on affordability and trust-building to foster green purchasing. This aligns with Egypt’s national target of increasing green public investments to 50% by 2024/2025, as part of a broader USD 40 billion commitment to renewable energy projects in the Suez Canal Economic Zone [114]. In both countries, businesses are strongly encouraged to move beyond superficial sustainability claims and avoid greenwashing. Instead, they should adopt transparent, verifiable sustainability practices to engage increasingly environmentally conscious yet financially constrained consumers. Recent public–private investments totalling EGP 1.2 billion in plastic recycling further demonstrate progress toward circular economy models [115].

Global corporations operating in Egypt and Jordan often introduce sophisticated greenwashing tactics, leveraging high-budget marketing campaigns to create eco-friendly images that frequently contradict their actual environmental footprints [19]. These practices normalise misleading communication and make it harder to establish a transparent green market. Policymakers in both countries should therefore prioritise verified sustainability reporting and develop robust regulatory frameworks to combat both greenwashing and greenhushing—where firms underreport sustainability actions to avoid scrutiny [50,112].

At the policy level, governments are already taking action. Egypt’s Ministry of Environment has launched a nationwide guide for environmental sustainability standards and invested EGP 250 million in an advanced waste recycling plant in Assiut [22]. Similarly, Jordan’s National Green Growth Plan integrates environmental goals into broader economic strategies. Socially, promoting genuine green behaviours enhances public health, as evidenced by Egypt’s initiatives to regulate industrial emissions and reduce plastic use. These efforts underline the need for an integrated approach combining policy support, corporate integrity and consumer education to drive meaningful, long-term behavioural change in emerging markets.

This study also offers several actionable recommendations for advancing sustainable consumer behaviour in Egypt, Jordan and similar emerging markets: Policymakers are encouraged to create supportive environments by enforcing stricter regulations against greenwashing and implementing policies that lower price barriers for sustainable products. Furthermore, they could enhance transparency through third-party eco-label certification schemes, and implementing government-led audits of environmental claims could discourage greenwashing and improve market accountability [20]. Additionally, public awareness campaigns co-created with local NGOs, universities and the media—such as those shown to significantly enhance environmental literacy and pro-environmental intent among Egyptian youth [116] and Jordan’s successful water stewardship messaging [15]—can make sustainability initiatives culturally resonant and trusted. Tailored interventions that reflect the unique socio-economic and cultural dynamics of Egypt and Jordan will be vital in fostering authentic sustainable consumption.

For businesses, adopting transparent communication strategies and providing verified data to support environmental claims are critical for building and maintaining consumer trust [117]. Firms should also consider offering affordable green alternatives and engaging in public–private partnerships to reduce price barriers and extend the reach of sustainable products, particularly in low- and middle-income segments [118].

Local authorities should support businesses in adopting more environmentally friendly practices by encouraging the procurement of green products (such as electric vehicles) through targeted policy incentives. Additionally, investing in infrastructure development, such as expanding the availability and accessibility of charging stations, can help remove practical barriers and foster greater consumer confidence in sustainable choices [119].

5.3. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study has several limitations; despite the robustness of the SEM analysis, this study is not resistant to potential endogeneity issues, particularly reverse causality between financial attitude and green behaviour. For instance, consumers who engage in green purchasing may subsequently develop stronger financial awareness or attitudes. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data and lack of appropriate instruments, an instrumental variable (IV) analysis was not feasible in the current study. We acknowledge this as a limitation and recommend that future research uses longitudinal or panel data, or applies IV techniques to better isolate causal directions.

The focus on Egypt and Jordan may limit generalisability to countries with different socio-economic and cultural contexts. Broader studies across diverse developing markets, encompassing both urban and rural areas, could enhance external validity and uncover regional variations in green purchasing behaviour.

While the snowball sampling approach helped us reach our target population, it naturally directed us to a sample with a higher proportion of urban residents. This focus aligns with our intention to study green behaviour in urban centres, where people are more likely to encounter green products. However, we acknowledge that this limits the ability to generalize the findings to rural areas. We encourage future studies to include a more diverse geographic spread to better capture the full range of consumer behaviour. Self-reported data also risk social desirability bias, which future research could address through objective measures or experimental designs.

Furthermore, exploring additional moderators and mediators, such as cultural norms and consumer effectiveness, and conducting sector-specific analyses—especially in industries inclined toward greenwashing—may deepen insights into sustainable consumption.

Finally, sector-specific analyses may show industry-level challenges and opportunities, particularly in sectors where greenwashing is prevalent. Addressing these areas will help build a more comprehensive understanding of green purchasing behaviour and support the development of effective, context-sensitive strategies for advancing sustainability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.E. and M.R.B.; methodology, E.E. and M.R.B.; empirical analysis and findings, E.E. and M.R.B.; conclusion and recommendations, E.E.; supervision, M.O. and M.R.B.; project administration, M.O. and M.R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Matevz O. received funding from the European Union—Next Generation EU and the Ministry of Higher Education, Science and Innovation, Slovenia. Research was carried out within the project entitled “Establishing an environment for green and digital logistics and supply chain education”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wu, S.-W.; Chiang, P.-Y. Exploring the Mediating Effects of the Theory of Planned Behavior on the Relationships between Environmental Awareness, Green Advocacy, and Green Self-Efficacy on the Green Word-of-Mouth Intention. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidou, C.N.; Skarmeas, D. Gray shades of green: Causes and consequences of green skepticism. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 144, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.H.; Yang, Z.; Nguyen, N.; Johnson, L.W.; Cao, T.K. Greenwash and green purchase intention: The mediating role of green skepticism. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Shi, B. Impact of greenwashing perception on consumers’ green purchasing intentions: A moderated mediation model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.K.; Haddad, S.; Barakat, M. Does blockchain adoption engender environmental sustainability? The mediating role of customer integration. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024, 30, 558–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbarky, S.; Elgamal, S.; Hamdi, R.; Barakat, M.R. Green supply chain: The impact of environmental knowledge on green purchasing intention. Supply Chain. Forum Int. J. 2023, 24, 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Shafy, H.I.; Mansour, M.S. Solid waste issue: Sources, composition, disposal, recycling, and valorization. Egypt. J. Pet. 2018, 27, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Abel, T.; Guagnano, G.A.; Kalof, L. A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 1999, 6, 81–97. [Google Scholar]

- Chuah, S.H.-W.; El-Manstrly, D.; Tseng, M.-L.; Ramayah, T. Sustaining customer engagement behavior through corporate social responsibility: The roles of environmental concern and green trust. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hameed, I.; Hyder, Z.; Imran, M.; Shafiq, K. Greenwash and green purchase behavior: An environmentally sustainable perspective. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 13113–13134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavuri, R. Organic green purchasing: Moderation of environmental protection emotion and price sensitivity. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 368, 133113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, J. Development strategies for green hydrogen, green ammonia, and green methanol in transportation. Renew. Energy 2025, 246, 122904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanin, I.; Serra, P.; Iskander, J.; Gamboa-Zamora, S.; Shen, L.; Liu, Y.; Knez, M. Is the inland waterways system primed for mitigating road transport in Egypt? Int. Bus. Logist. 2024, 4, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.M.; Barky, S.S.S.E.; Barakat, M.R. Exploring Egyptian Consumers’ Drive for Sustainable Purchases through Financial Empowerment and Environmental Awareness: The Moderating Role of Demographic Characteristics. J. Sustain. Res. 2025, 7, e250011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedict, S.; Hussein, H. An analysis of water awareness campaign messaging in the case of Jordan: Water conservation for state security. Water 2019, 11, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishal, A.; Dubey, R.; Gupta, O.K.; Luo, Z. Dynamics of environmental consciousness and green purchase behaviour: An empirical study. Int. J. Clim. Change Strateg. Manag. 2017, 9, 682–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Arshad, A.; Anwar ul Haq, M.; Akram, B. Role of environmentalism in the development of green purchase intentions: A moderating role of green product knowledge. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2020, 15, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhutto, M.H.; Tariq, B.; Azhar, S.; Ahmed, K.; Khuwaja, F.M.; Han, H. Predicting consumer purchase intention toward hybrid vehicles: Testing the moderating role of price sensitivity. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 62–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eric, K. Greenwashing Examples 2024: Top 10 Greenwashing Companies. Available online: https://energytracker.asia/greenwashing-examples-of-top-companies/ (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Bhullar, P.S.; Joshi, M.; Sharma, S.; Kaur, A.; Phan, D. Greenwashing and ESG: Bibliometric analysis and future research agenda. Pac.-Basin Financ. J. 2025, 93, 102846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekhit, S.A.; Rafei, R.; Elnaggar, F.; Al-Sakkaf, O.Z.; Seif, H.K.; Samardali, D.; Alabead, Y.T.; Sanosi, M.O.O.; Abdou, M.S.; Elbanna, E.H.; et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and self-reported practices regarding cholera among six MENA countries following cholera outbreaks in the region. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State-Information-Service. Ministry of Environment: LE 250M Investment to Launch Advanced Waste Recycling Plant in Assiut. Available online: https://www.sis.gov.eg/Story/202578/Ministry-of-Environment-LE-250M-investment-to-launch-advanced-waste-recycling-plant-in-Assiut (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Dabees, A.; Lisec, A.; Elbarky, S.; Barakat, M. The role of organizational performance in sustaining competitive advantage through reverse logistics activities. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024, 30, 2025–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.; Wu, J.S.; Tipi, N. Empowering Clusters: How Dynamic Capabilities Drive Sustainable Supply Chain Clusters in Egypt. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alashiq, S.; Aljuhmani, H.Y. From Sustainable Tourism to Social Engagement: A Value-Belief-Norm Approach to the Roles of Environmental Knowledge, Eco-Destination Image, and Biospheric Value. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, K.; Pang, X. Investigation into the factors affecting the green consumption behavior of China rural residents in the context of dual carbon. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, B.; Sheng, G.; She, S.; Xu, J. Impact of consumer environmental responsibility on green consumption behavior in China: The role of environmental concern and price sensitivity. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.P.M.; Van Nguyen, P.; Stokes, P. Green influencers and consumers’ decoupling behaviors for parasocial relationships and sustainability. A comparative study between Korea and Vietnam. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 84, 104256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Ahsan, M.N.; Kokash, H.A.; Ahmed, S.; Di, W. Remanufactured consumer goods buying intention in circular economy: Insight of value-belief-norm theory, self-identity theory. J. Remanuf. 2025, 15, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawed, F.; Iqbal, S.; Bilal, A.; Amir, F. Sustainable consumption in fashion—The role of public self-consciousness and a comparison of existing-consumers versus new-consumers. S. Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haj-Salem, N.; Ishaq, M.I.; Raza, A. How anticipated pride and guilt influence green consumption in the Middle East: The moderating role of environmental consciousness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 68, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Fu, Q.; Thomopoulos, N.; Chen, J.L. Understanding the influence of past driving experience on electric vehicle purchase intention in China. Transp. Policy 2025, 162, 270–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElHaffar, G.; Durif, F.; Dubé, L. Towards closing the attitude-intention-behavior gap in green consumption: A narrative review of the literature and an overview of future research directions. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, F.; Adhikari, A. Antecedents affecting consumers’ green purchase intention towards green products. Am. J. Interdiscip. Res. Innov. 2023, 1, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.; El-Rouby, H.S.; El-Gamal, S.Y.; Zaghloul, A.S. The Tendency Toward Producing Ecologically Friendly Products at Toshiba in the Middle East. In Cases on International Business Logistics in the Middle East; Abdelbary, I., Haddad, S., Elkady, G., Eds.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2023; pp. 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cam, L.N.T. A rising trend in eco-friendly products: A health-conscious approach to green buying. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, A.; Tong, X. Factors influencing college students’ purchase intention towards Bamboo textile and apparel products. Int. J. Fash. Des. Technol. Educ. 2016, 9, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laheri, V.K.; Lim, W.M.; Arya, P.K.; Kumar, S. A multidimensional lens of environmental consciousness: Towards an environmentally conscious theory of planned behavior. J. Consum. Mark. 2024, 41, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahma, B.; Kramberger, T.; Barakat, M.; Ali, A.H. Investigating customers’ purchase intentions for electric vehicles with linkage of theory of reasoned action and self-image congruence. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, V.H.; Wickli, N.; Siegrist, M. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. J. Environ. Psychol. 2016, 45, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, S.; Lopes, J.M.; Nogueira, S. Willingness to pay more for green products: A critical challenge for Gen Z. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 390, 136092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, N.; Lee, K. Environmental consciousness, purchase intention, and actual purchase behavior of eco-friendly products: The moderating impact of situational context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, N.; Ghutai, G.; Yousafzai, M.T.; Ahmad, S. Pricing the Green Path: Unveiling the role of Price Sensitivity as a Moderator in Environmental Attitude and Green Purchase Intentions. Int. Rev. Manag. Bus. Res. 2023, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Guath, M.; Stikvoort, B.; Juslin, P. Nudging for eco-friendly online shopping–Attraction effect curbs price sensitivity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 81, 101821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatu, V.M.H.; Mat, N.K.N. Predictors of green purchase intention in Nigeria: The mediating role of environmental consciousness. Am. J. Econ. 2015, 5, 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, M.A.; Kramberger, T.; Barakat, M.; Ali, A.H. Barriers to Applying Last-Mile Logistics in the Egyptian Market: An Extension of the Technology Acceptance Model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbu, A.; Catană, Ș.-A.; Deselnicu, D.C.; Cioca, L.-I.; Ioanid, A. Factors influencing consumer behavior toward green products: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarabieh, S. The impact of greenwash practices over green purchase intention: The mediating effects of green confusion, Green perceived risk, and green trust. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2021, 11, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, I.; Kassinis, G.; Papagiannakis, G. The impact of perceived greenwashing on customer satisfaction and the contingent role of capability reputation. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 185, 333–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayoub, D.; Awad, R. The Effect of Greenwashing on Consumers’ Green Purchase Intentions. المجلة العربية للإدارة 2024, 44, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lylla, Y. Dismantling the Greenwashing Machine: Strategies from Below. Available online: https://thepublicsource.org/green-colonialism-capitalism (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Deshmukh, P.; Tare, H. Green marketing and corporate social responsibility: A review of business practices. Multidiscip. Rev. 2024, 7, e2024059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.; Obrecht, M.; Ali, A.H.; Barakat, M. Does environmental knowledge and performance engender environmental behavior at airports? A moderated mediation effect. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2024, 30, 671–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eid, A.; Salah, M.; Barakat, M.; Obrecht, M. Airport Sustainability Awareness: A Theoretical Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (Multivariate Applications Series); Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010; Volume 396, p. 7384. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2009-14446-000 (accessed on 3 August 2025).

- Matthews, L.; Hair, J.; Matthews, R. PLS-SEM: The holy grail for advanced analysis. Mark. Manag. J. 2018, 28, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher, K.J.; Rucker, D.D.; Hayes, A.F. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2007, 42, 185–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, S.K.; Haddad, S.; Barakat, M.; Rosi, B. Blockchain technology adoption for improved environmental supply chain performance: The mediation effect of supply chain resilience, customer integration, and green customer information sharing. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordanian Ministry of Environment. Waste Sector Green Growth National Action Plan 2021–2025; Jordanian Ministry of Environment: Amman, Jordan, 2020. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC201802/ (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Leaders International. The Green Economy in Jordan: Sustainability Leading the Way for Growth. Available online: https://leadersinternational.org/results-insights/the-green-economy-in-jordan-sustainability-leading-the-way-for-growth/? (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Saad, N.; Barakat, M. Exploring the Impact of Lean, Agile, Resilient, and Green (LARG) Supply Chain Practices on Organizational Performance through Mediating Role of Big Data Analytics. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2025, 22, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.; El-Gamal, S.Y.; Elbarky, S.; Barakat, M.R. The impact of reverse logistics decision on environmental and social performance: The role of green integration and blockchain. Int. J. Integr. Supply Manag. 2024, 17, 323–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.H.; Barakat, M.R. Enhancing sustainability performance through absorptive capacity: The moderating role of environmental uncertainty. Int. J. Procure. Manag. 2024, 19, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M.; Ali, A.; Madkour, T.; Eid, A. Enhancing operational performance through supply chain integration: The mediating role of resilience capabilities under COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Logist. Syst. Manag. 2024, 47, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabees, A.; Barakat, M.; Lisec, A. Investigation factors affecting Agri-food waste in Retailers entities: Evidence from Egypt. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Logistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 7–10 July 2024; p. 298. Available online: https://www.islconf.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/ISL_2024_Proceedings_-1.pdf (accessed on 4 August 2025).