Abstract

Both behavioral intentions and structural constraints shape household waste disposal in low-resource settings. This study integrates the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) with Environmental Justice (EJ) to examine informal waste disposal in Vhembe District, South Africa, a region marked by infrastructural deficits and uneven municipal services. A cross-sectional survey of 399 households across four municipalities assessed five disposal behaviors, including river dumping and domestic burial. Only 8% of households used formal bins, while over 50% engaged in open or roadside dumping. Although education and income were inversely associated with harmful practices, inadequate service access was the most significant constraint on formal disposal. Logistic regression revealed that rural residents and households in underserved municipalities were significantly more likely to engage in hazardous methods, regardless of socioeconomic status. These findings extend TPB by showing that perceived behavioral control reflects not only psychological agency but also material and institutional limitations. By reframing informal disposal as a structurally conditioned response rather than a behavioral deficit, the study advances EJ theory and provides a transferable TPB–EJ framework for decentralized, justice-oriented waste governance. The results underscore the need for Sustainable Development Goal (SDG)-aligned interventions that integrate equitable infrastructure with context-sensitive behavioral strategies.

1. Introduction

The rapid increase in municipal solid waste (MSW) presents a significant environmental and governance challenge globally, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where formal waste management systems are underdeveloped. Projections indicate that global waste generation will rise from 2.01 billion tons in 2016 to 3.40 billion tons by 2050, with the most pronounced growth expected in LMICs [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa, over 60% of the population lacks access to reliable waste collection services, leading to dependence on informal and often hazardous disposal methods such as burning, open dumping, and burial [2,3,4]. These practices contribute to the transmission of communicable diseases, groundwater contamination, and air pollution, thereby posing threats to human and ecosystem health and hindering progress towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3, 6, 11, and 12 [5,6,7].

In South Africa, these issues are exacerbated by historical and spatial inequalities in waste service provision [8,9]. Only 64% of households receive regular waste removal, with significantly lower coverage in rural provinces such as Limpopo [10,11]. In the Vhembe District, diverse settlement types, ranging from rural villages and farms to peri-urban townships, are characterized by fragmented service delivery, infrastructural undercapacity, and procedural exclusion, particularly in informal and underserved communities [12,13]. These structural constraints render informal waste disposal not merely a matter of choice but also an adaptive response to systemic neglect. This neglect reflects not only local governance gaps but also broader failures in policy implementation. South Africa’s waste management is guided by the Waste Act (No. 59 of 2008) and the National Waste Management Strategy [14,15], which promotes sustainable and equitable service delivery. However, gaps persist between policy intent and delivery, especially in marginalized regions, reinforcing the need for frameworks that address both behavioral intent and structural constraints.

Theoretical approaches to household waste behavior have traditionally drawn on psychological frameworks, notably the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), which explains individual decision-making through the constructs of attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control [16,17,18]. The TPB has demonstrated predictive validity in urban and high-resource contexts, including recent extensions to waste separation in children [19] and willingness to pay for waste services [4,20]. However, in LMIC rural contexts, where infrastructural support is absent or erratic, the model’s assumptions regarding volitional control are often untenable [4,21]. Constrained material conditions can suppress behavioral execution, regardless of positive intention, limiting the TPB’s utility in these environments.

To address these shortcomings, scholars have increasingly incorporated structural frameworks such as Environmental Justice (EJ), which examines how institutional, spatial, and procedural inequalities mediate environmental exposure and access to services [22,23,24,25,26]. Recent studies have emphasized the value of integrating TPB with EJ, reconceptualizing perceived behavioral control to reflect both individual agency and structural constraints [18]. Despite its conceptual appeal, the empirical application of TPB–EJ integration remains limited, particularly in rural African contexts, where environmental marginality intersects with socio-demographic exclusion.

This study addresses a significant empirical and conceptual gap by employing an integrated TPB–EJ framework to analyze household waste disposal practices in the Vhembe District of Limpopo Province. The district’s diverse settlements, infrastructural disparities, and governance asymmetries present a compelling case for examining the intersection of structural and behavioral factors in shaping waste management outcomes. Utilizing survey data from 399 households across four local municipalities, the analysis disaggregated informal disposal behaviors into river dumping, roadside disposal, and burial within compounds. This analysis advances current theoretical debates by operationalizing perceived behavioral control as both a psychological disposition and a function of external material and institutional realities. Furthermore, the findings provide empirical specificity to national policy debates by highlighting underreported disposal behaviors and supporting the call for more inclusive, decentralized waste governance systems aligned with SDGs 11.6 and 12.5.

2. A Review of the Theoretical Framework

Effective household waste management in resource-limited environments is influenced by the complex interplay of individual perceptions, socio-cultural norms, and structural inequalities. Analyzing rural households’ decision-making, particularly in the absence of reliable waste collection services, necessitates an analytical framework that considers not only behavioral intent but also the broader spatial and institutional contexts in which these behaviors occur. This study employs two complementary theoretical models: the TPB and the EJ framework.

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB)

The TPB, developed by Ajzen [16], has been widely used to understand pro-environmental behaviors, including recycling, litter prevention, energy conservation, and waste sorting. This model suggests that behavior is influenced by three constructs: attitudes towards the behavior, encompassing beliefs about its consequences; subjective norms, referring to perceived social pressures; and perceived behavioral control, which relates to the perceived ease of performing the behavior based on past experiences and obstacles.

In the context of household waste disposal, the TPB has been used to evaluate how individuals form intentions for proper waste management, such as utilizing municipal collection services and avoiding illegal dumping [18,21,27]. However, in low-service environments like Vhembe, perceived behavioral control is constrained by external conditions, such as the absence of waste bins, infrequent collection, or distant disposal sites. These constraints render high behavioral intent ineffective, highlighting a limitation of the TPB in material deprivation contexts.

Recent empirical studies have reinforced TPB’s utility in LMICs’ waste behavior research. Moeini et al. [17] systematically reviewed TPB applications and found that perceived behavioral control is often the strongest predictor of waste separation when infrastructure exists. In Nigeria, Eremionkhale et al. [28] found that subjective norms and control beliefs significantly influenced urban households’ participation in recycling programs. Similarly, Babazadeh et al. [29] and Alam et al. [30] applied the TPB to solid waste management in Iran and showed that interventions focused on enhancing perceived control improved behavioral outcomes.

In rural India, Haque et al. [4] integrated TPB with environmental concern constructs and found that social pressure from community leaders shaped attitudes towards formal disposal methods. These findings reinforce the context-sensitive adaptation of the TPB to settings with fragmented services. Furthermore, Amir et al. [18] applied the TPB in Vietnam and showed that knowledge alone is insufficient; logistical and policy support are needed to activate intention.

2.2. Environmental Justice (EJ)

The EJ framework shifts the focus from individual decision-making to systemic inequalities in environmental risk distribution. Initially developed in the United States to address racialized exposure to environmental hazards, the EJ framework has expanded to examine inequalities related to class, space, ethnicity, and governance [22,23,31,32]. The EJ paradigm rests on three dimensions: distributional justice, concerning the equitable allocation of environmental goods and burdens; procedural justice, addressing fairness in environmental decision-making; and recognitional justice, acknowledging diverse identities and experiences in environmental governance. In rural waste management, EJ reveals how historical, political, and economic processes create spatial inequalities in service access and delivery.

Recognitional justice highlights how waste policies often ignore local knowledge, cultural practices, and traditional leadership. In Vhembe, backyard waste burial may be a practical response to service gaps, not ignorance. Yet such practices are often dismissed, showing that local ways of knowing are undervalued.

In the Vhembe District, communities in remote or informal settlements lack regular municipal waste services (MWSs). This exclusion stems from structural disinvestment, inadequate planning, and institutional fragmentation. The EJ framework reinterprets informal disposal practices as adaptive responses to service gaps rather than deviant behavior, understanding these behaviors in the context of broader social conditions.

Recent studies support the application of EJ in waste governance. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) [26], the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA) [33], and the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Center for Health Justice [34] linked the EJ to health disparities from waste exposure in marginalized communities. In Africa, Akenji et al. [35] argued that the lack of procedural and recognitional justice drives centralized waste policy failures. In Brazil, Schneider et al. [36] showed how informal recyclers face systemic barriers despite their environmental contributions. Studies from South and Southeast Asia, by Urme et al. [37] in Bangladesh and Zulkipli et al. [38] in Malaysia, use EJ principles to reveal the socio-political roots of spatial dumping. These studies confirm that informal waste practices are structurally determined rather than resulting from ignorance alone. While the TPB explains behavioral motivation, EJ contextualizes structural constraints, and their integration enables a multi-level analysis of household disposal behavior. The following section outlines the conceptual structure and operationalization of this integration.

2.3. An Integrated Framework: Behaviour Within Structural Constraint

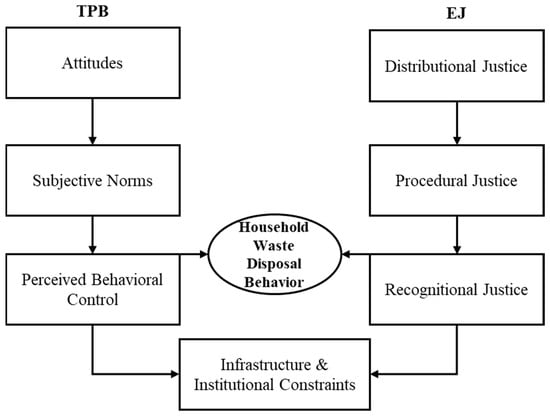

Although the TPB and EJ have been extensively applied in environmental research, their combined application remains limited in the rural African context. This study proposes the integration of TPB and EJ, acknowledging that behavior is both intentional and structurally conditioned. In this framework, the TPB captures the influence of individual attitudes, perceived norms, and behavioral control on waste-related intentions at the household level. EJ examines the spatial and institutional forces that facilitate or hinder such behaviors.

This integration is particularly relevant to perceived behavioral control. Within TPB, this concept refers to an individual’s perception of their ability to perform a specific behavior. From the EJ perspective, perceived control reflects both psychological state and material/institutional realities. For example, a household may be environmentally conscious and willing to use formal disposal services but unable to do so because of a lack of infrastructure or regulatory neglect.

As illustrated in Figure 1, behavioral outcomes are constrained by psychological and structural factors. The operationalization of theoretical constructs is summarized in Table 1, which maps each variable to its position within the integrated TPB–EJ framework, showing the measurement type, justice dimension, and alignment with the SDGs. The framework analyzes the behavioral intentions and systemic constraints of household waste disposal. These constraints directly influence the feasibility of pro-environmental action. By reinterpreting behavioral control through psychological and structural lenses, the model enables a realistic understanding of waste management practices in low-resource settings, including the Philippines, where similar infrastructural constraints and informal disposal behaviors have been empirically observed [39]. This approach aligns with SDGs 11 and 12, which advocate inclusive waste governance systems. This provides a basis for empirical analysis, linking socio-demographic, spatial, and infrastructural variables to waste disposal practices in the Vhembe District.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework integrating TPB and EJ constructs to interpret household waste disposal patterns. Arrows indicate theorized influence, not tested relationships.

Table 1.

Conceptual mapping of integrated TPB–EJ constructs to study variables and relevant SDGs.

This conceptual model synthesizes the TPB with the EJ framework. Within this model, behavioral intention is influenced by attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, as outlined in the TPB. However, the actualization of this intention is either constrained or facilitated by infrastructural and institutional conditions, as described in the EJ framework. In environments with limited resources, perceived behavioral control is redefined as contingent upon material and governance systems rather than solely on individual volition. This integration enables the TPB to incorporate both individual-level determinants of behavior and the structural constraints emphasized by EJ. While TPB explains how attitudes, social norms, and perceived behavioral control shape behavioral intentions, it assumes that individuals can act on those intentions. In low-resource settings, however, this capacity is often constrained by limited infrastructure, spatial exclusion, and unequal access to services, dimensions that are central to the EJ framework. By combining these perspectives, the TPB–EJ model offers a more comprehensive explanation of informal waste disposal practices, framing them not as irrational or negligent behaviors, but as adaptive responses to systemic inequities. This theoretical synthesis enhances explanatory power and provides a stronger foundation for designing context-sensitive and equity-oriented waste management policies in marginalized communities.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Area and Design

This study was conducted in the Vhembe District of Limpopo Province, South Africa, encompassing four municipalities: Makhado, Musina, Collins Chabane, and Thulamela. These areas are characterized by diverse settlement types, including rural villages, farms, and peri-urban towns. A cross-sectional household survey was conducted to investigate the socio-demographic and infrastructural determinants influencing waste disposal behavior.

A multistage sampling approach was employed, beginning with the purposive selection of residential clusters to capture variations in access to waste services. The study area was first stratified by municipality (Makhado, Musina, Collins Chabane, and Thulamela), followed by further stratification by settlement typology: rural villages, farms, townships, and city centers to ensure proportional representation of marginalized communities. Within each cluster, households were selected using systematic random sampling based on local household registers or guided by community leaders in areas lacking formal records. The four municipalities collectively comprise approximately 436,959 households [40]. Using Krejcie and Morgan’s formula [41] for known populations, a minimum of 385 households was required for statistical validity. Hence, a total of 400 households were surveyed (approximately 100 per municipality), with one case excluded due to missing data, resulting in a final sample of 399 households, with a response rate of 99.75%.

3.2. Survey Instrument and Data Collection

Data collection was conducted from May to July 2024 using a structured questionnaire, which was administered through face-to-face interviews with an adult respondent (≥18 years) in each household. The instrument was initially developed in English and subsequently translated into Tshivenda and Xitsonga by trained, bilingual fieldworkers. A pilot test involving 20 households not included in the study sample was performed to enhance item clarity. The instrument included Likert-scale items to measure TPB constructs such as attitudes and perceived behavioral control. Binary items captured variables like environmental concern and access to services. Subjective norms were proxied through reported reuse and recycling practices.

3.3. Data Analysis

Survey responses were systematically coded, cleaned, and analyzed using SPSS (Version 27) and R (Version 4.2). One incomplete questionnaire was excluded, resulting in a final analytical sample of 399 households in the study. Item-level missing data across the remaining cases were minimal (<1%) and were addressed through a listwise deletion.

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages, were initially computed for all key variables, including household demographics, socioeconomic characteristics, waste production patterns, and disposal behaviors. These summaries, presented in Table 2, provide an empirical foundation for subsequent inferential analysis. To investigate the determinants of household waste disposal behavior, a series of five binary logistic regression models were estimated, each with one of the following binary dependent variables (1 = use, 0 = non-use): (a) use of formal bin collection, (b) dumping in rivers, valleys, or lakes, (c) roadside dumping, (d) disposal in open public spaces, and (e) burial of waste within the household compound. The independent variables included municipality, residential location type, gender, age group, education level, employment status, household income, household size, and length of residence. The service-related variables included access to waste collection (public/private/none) and the presence of a bin within 1 km. All variables were selected and operationalized based on the integrated TPB–EJ conceptual framework detailed in Table 1, ensuring theoretical coherence in translating constructs such as attitudes, perceived control, and justice dimensions into measurable variables relevant to multivariate analysis. Categorical variables were dummy-coded using the following reference categories: Makhado (municipality), rural village (settlement type), female (gender), no formal education (education), unemployed (employment), and income below ZAR 10,000/month (household income).

Table 2.

Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of respondents (n = 399).

Results are reported as adjusted odds ratios (AORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and a significance threshold of α = 0.05 was employed. No interaction terms were tested, and model diagnostics were not performed at this stage. The sampling weights were omitted. This analytical approach aligns with the study’s explanatory aim of assessing how socio-demographic, spatial, and service-related variables collectively influence the observed variability in household waste disposal outcomes, particularly in contexts characterized by infrastructural inequity.

3.4. Demographic and Socioeconomic Profile of Respondents

Among the 399 valid responses analyzed, households were nearly evenly distributed across the four municipalities: Makhado (24.8%), Musina (25.1%), Collins Chabane (25.1%), and Thulamela (25.1%), as shown in Table 2. This proportional allocation ensured a balanced geographical representation, thereby enhancing the robustness of cross-municipal comparisons. Regarding settlement typology, most respondents resided in rural areas (35.8%) or on farms (27.1%), followed by those living in townships (21.8%) and city centers (15.3%).

The demographic composition was predominantly female (61.4%), with the majority aged between 18 and 39 years (56.1%), indicating a relatively young population structure. Household sizes were typically large, with nearly half (47.4%) reporting 5–6 members. Additionally, 34.8% had resided in their current location for over two decades, suggesting strong community ties and potential implications for long-term waste-behavior patterns.

The educational attainment was modest, with 35.6% having completed secondary education and 21.6% holding university degrees. A smaller fraction (3.8%) reported that they had never attended school. Employment status varied: 33.1% were unemployed, 37.1% were self-employed, and 17.0% were employed in the public sector. Income distribution revealed financial vulnerability, with 43.1% earning less than ZAR 10,000 per month. These socioeconomic characteristics provide an essential context for understanding differential waste disposal practices and access to waste services across demographic groups.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Durban University of Technology Research Ethics Committee (Ethics Clearance Number: IREC 294/22). Informed consent was obtained from all the participants. The data were anonymized and securely stored on an encrypted server. Additionally, community permission was obtained from municipal authorities in all participating areas.

3.6. Methodological Limitations

This study employed an exploratory and interpretive design. Although logistic regression was used to identify associations between socio-demographic and service access factors and disposal behaviors, the objective was not to statistically validate a formal theory. Instead, this study seeks to understand the structural influences on household-level practices. However, the regression analysis does not fully capture the underlying reasons for hazardous disposal behaviors. Future research should incorporate qualitative methods to provide deeper insight into behavioral motivations and structural adaptations.

4. Results

4.1. Waste Production Behavior

4.1.1. Waste Collection Services

The data indicate that waste collection services are primarily administered by private entities, with 81% of respondents utilizing these services. Conversely, only 14.3% of respondents relied on public waste collection services, suggesting a diminished level of government participation in this sector. A minor segment (4.8%) relies on alternative forms of waste collection.

4.1.2. Availability of Public Bins Within 1 km from House

The data revealed that a substantial proportion of respondents (78.2%) lacked access to public waste bins within a 1-kilometer radius of their residences. Conversely, only 21.8% of respondents reported the availability of public bins within this distance. This disparity highlights a notable deficiency in waste management infrastructure that may pose challenges to effective waste disposal. The absence of proximate public bins could exacerbate improper waste disposal practices, such as illegal dumping or littering, and underscores the necessity for enhanced waste management planning and service delivery in the region to address this issue.

4.1.3. How Long Does It Take to Get There?

Among respondents residing within one kilometer of public waste disposal bins, the convenience of waste disposal exhibited considerable variation. Specifically, 37.9% of the individuals had a bin located directly outside their residence, facilitating immediate and effortless waste disposal. Conversely, 28.7% are required to walk between 5 and 10 min, while 11.5% must walk 11–15 min to access the nearest bin. A smaller segment of the population experienced even longer travel times, with 5.7% needing 16–20 min and another 5.7% requiring 21–25 min. Additionally, 10.3% of respondents reported a walking time of 25 min to reach a public bin.

These data underscore that, although some residents enjoy convenient access to waste disposal facilities, a significant proportion must traverse considerable distances, potentially discouraging proper waste disposal and contributing to littering or illegal dumping. Enhancing the distribution of public bins could improve waste management efficiency and promote better disposal practices in affected areas.

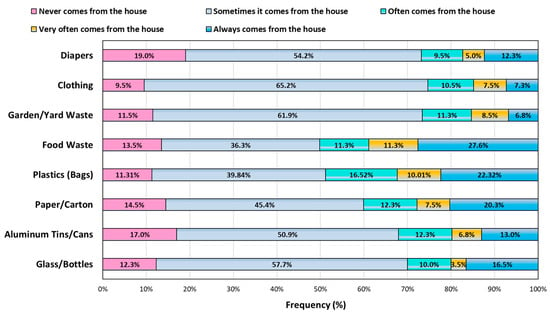

4.1.4. Type of Solid Waste That Comes from the Household

Households were surveyed regarding the types and frequency of solid waste generated. The waste stream in this rural district is notably heterogeneous, reflecting the diverse household activities. Figure 2 illustrates that households produce various types of solid waste at different frequencies. Clothing and garden or yard waste were among the most frequently discarded items, with 65.2% and 61.9% of households, respectively, indicating that these waste types occasionally originate from their homes. This suggests that clothing disposal may occur seasonally or as part of decluttering efforts, whereas yard waste is likely influenced by gardening activities and seasonal changes.

Figure 2.

Types of solid waste commonly generated by households.

Glass bottles (57.6%), diapers (54.1%), and paper or carton waste (45.4%) are also commonly discarded, although their frequencies vary among households. Notably, plastic bags (39.8%), food waste (36.3%), and aluminum tins/cans (50.9%) were reported to “sometimes” originate from households, highlighting their presence but perhaps also the influence of waste reduction efforts, such as reusable bags or composting initiatives. Conversely, a smaller percentage of households reported that certain waste types never originated from their homes. For instance, 12.3% of households did not generate glass waste, whereas 9.5% reported never discarding clothing or diapers. This variation likely reflects differences in household composition, lifestyle choices, and consumption habits; for example, homes without infants would not generate diaper waste, whereas households that prioritize recycling may have lower glass or aluminum waste output.

4.2. Waste Disposal Behaviors

The data indicate that most households predominantly utilize informal waste disposal methods, with only 8% reporting the use of bins for waste disposal. This suggests a substantial deficiency in access to formal waste collection services or a general inclination towards alternative disposal methods. The overwhelming 92% of households not utilizing bins implies a potential inadequacy in waste management infrastructure in many regions.

Alarmingly, 23.8% of households acknowledged waste disposal in valleys, lakesides, or rivers, posing significant environmental and health hazards. Similarly, 22.6% of respondents disposed of waste on roadsides or streets, exacerbating urban pollution and sanitation issues. Although these practices are not adopted by the majority, the fact that nearly one in four households engages in them underscores the necessity of improved waste management interventions.

Open dumping in public spaces is relatively uncommon, with only 3% of households employing this method, whereas 97% refrain from it. However, a significant 41.4% of households bury their waste within their compounds, a practice that, despite its convenience, can result in soil contamination and long-term environmental repercussions.

The findings, summarized in Table 3, reveal a pronounced reliance on informal and occasionally hazardous waste disposal methods. The prevalent lack of bin usage and the high incidence of dumping in natural areas and on roadsides highlight serious deficiencies in waste management.

Table 3.

Patterns of waste disposal in the community.

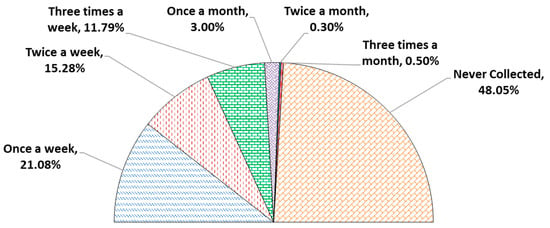

4.3. How Often Is the Waste Container Emptied by the Local Municipality?

Figure 3 shows the frequency with which waste containers are serviced by local municipal authorities. The data revealed substantial disparities in waste collection services, with nearly half of the respondents (48.1%) indicating that their waste was never collected by municipal services. This finding suggests a significant deficiency in formal waste management infrastructure, which may contribute to increased illegal dumping, environmental hazards, and sanitation challenges. Among those who received waste collection services, 21.1% of households had their waste containers emptied once a week, representing the most common frequency for those receiving the service. Furthermore, 15.3% of respondents reported waste collection occurring twice a week, while 11.8% had their waste collected three times per week. Less frequent waste collection is reported by a small percentage of households, with 3% experiencing waste collection once a month and a very small number of households receiving service twice a month (0.3%) or thrice a month (0.5%).

Figure 3.

Frequency of municipal waste collection as reported by households.

4.4. Unadjusted Odds Ratios for Predictors of Household Waste Disposal Methods

Binary logistic regression models assessed associations among socio-demographic, economic, and spatial variables and five household waste disposal practices: (1) disposal in formal bins, (2) dumping in valleys, rivers, or lakesides, (3) disposal on roadsides or street edges, (4) dumping in open spaces, and (5) burying waste in household compound holes. Each model used a single predictor, yielding crude ORs with 95% CIs and p-values for each variable. Table 4 presents the outcomes of simple binary logistic regression models.

Table 4.

Results of binary logistic regression of housing characteristics, socio-demographic factors, and environmental health risk factors regarding waste disposal methods.

The following are the key findings.

4.4.1. Geographical Differences

The binary logistic regression analysis shows that, compared to Makhado, Musina residents had a lower propensity to dispose of waste in bins (OR = 0.2, p = 0.010). However, they showed a higher likelihood of discarding waste in valleys, lakesides, or rivers (OR = 156, p < 0.001). The probability of these residents disposing of waste in a hole within their compound was reduced (OR = 0.06, p < 0.001). In contrast, Collins Chabane Municipality showed increased likelihood of waste disposal on roadsides (OR = 15.1, p < 0.001) and decreased likelihood of using a hole within their compound (OR = 0.2, p < 0.001). Similarly, Thulamela Municipality residents were more likely to dispose of waste on roadsides (OR = 28.4, p < 0.001) and less likely to use a hole within their compound (OR = 0.2, p < 0.001).

4.4.2. Type of Residential Location

Residents of rural areas demonstrated a significantly higher propensity to dispose of waste in valleys, lakesides, or rivers (OR = 5.4, p < 0.001), while exhibiting a markedly lower likelihood of depositing waste along roadsides (OR = 0.1, p < 0.001). Conversely, individuals residing in townships were predominantly inclined to utilize bins for waste disposal (OR = 14, p < 0.001) and were less prone to discard waste in valleys (OR = 0.1, p < 0.003). However, township residents also showed a modestly increased tendency to dispose of waste on roadsides (OR = 1.8, p = 0.041). Notably, gender did not present significant correlations with waste disposal practices, as the odds ratios comparing males to females did not reveal substantial differences across the various disposal categories.

4.4.3. Gender

In the adjusted analysis, sex did not significantly affect disposal behavior. The odds ratios for male-headed households, compared to female-headed households, did not demonstrate statistical differences for any disposal method. This indicates that when controlling for other variables, gender does not determine whether a household engages in dumping or utilizes bins. Although women often manage daily household waste, the ultimate disposal decisions, particularly for large-scale dumping, may involve both genders. Our data suggest that gender parity in behavior may also reflect the influence of community norms and infrastructure limitations, which may supersede individual gender tendencies.

4.4.4. Age

Analysis of age-related waste disposal behaviors revealed that individuals within the older age brackets, specifically those aged 50–59 years and 60–69 years, exhibited a markedly higher propensity to utilize waste bins (OR = 3.8, p = 0.022 and OR = 7.1, p = 0.008, respectively). Conversely, individuals aged 40–49 and 50–59 years demonstrate a significantly increased likelihood of disposing of waste in valleys, lakesides, or rivers (OR = 3.1, p < 0.001, and OR = 4.1, p < 0.001, respectively). Furthermore, those within the 40–49, 50–59, and 60–69 age groups were significantly less inclined to dispose of waste in a hole within their compound (p < 0.05).

4.4.5. Household Size and Length of Residence

Households comprising three to four members exhibited a significantly higher propensity to dispose of waste along roadsides (OR = 9.9, p = 0.028). In contrast, larger households consisting of five to six members demonstrated a markedly reduced likelihood of depositing waste in valleys (OR = 0.1, p < 0.001) and an increased tendency to utilize a hole within their compound for waste disposal (OR = 3.2, p = 0.023). Residents with a tenure of less than one year in the area were used as the reference group. Those residing in the area for one to five years and five to ten years exhibited a significantly diminished likelihood of employing a hole in their compound for waste disposal (p < 0.001). Similarly, individuals who have resided in the area for 15–20 years are significantly less inclined to dispose of waste in valleys (OR = 0.01, p < 0.010).

4.4.6. Education

Individuals without formal education were the reference group in this analysis. In comparison, those with a primary education exhibited a significantly higher likelihood of disposing of waste in valleys (OR = 3.6, p = 0.031). Conversely, individuals who had completed secondary education, undergraduate studies, or held university degrees demonstrated a markedly lower propensity to engage in such waste disposal practices (p < 0.001). Notably, university graduates were particularly inclined to utilize a hole within their compound for waste disposal (OR = 9.9, p = 0.004).

4.4.7. Employment Status

Unemployed individuals were used as the reference category in this analysis. The findings indicate that self-employed individuals exhibit a significantly higher propensity to dispose of waste in valleys (OR = 11.9, p < 0.001) and are less inclined to utilize a hole within their compound for waste disposal (OR = 0.3, p < 0.001). Conversely, farmworkers demonstrated a markedly higher likelihood of using a hole within their compound for waste disposal (OR = 5.3, p < 0.001) but were significantly less likely to dispose of waste on roadsides (OR = 0.1, p = 0.008).

4.4.8. Household Income

Households with an income of less than 10,000 serve as the reference category for income. Those with earnings between 10,000 and 30,000 were significantly more likely to dispose of waste in valleys (OR = 16.2, p < 0.001) and less likely to utilize a hole within their compound for waste disposal (OR = 0.4, p < 0.001). Similarly, households with an income ranging from 30,000 to 50,000 were significantly more inclined to dispose of waste in valleys (OR = 11.1, p < 0.001) and on roadsides (OR = 3.6, p < 0.001), while they were significantly less likely to use a hole within their compound (OR = 0.1, p < 0.001). The findings suggest that waste disposal behavior is strongly influenced by demographic, socioeconomic, and environmental factors.

There are significant differences in waste management practices among municipalities, with Musina and Thulamela exhibiting a high tendency for improper waste disposal. The location of residence is also a critical factor, with farms and rural areas showing a high propensity to dump waste in valleys. Additionally, age, education, and household income influence waste disposal habits; older individuals were more likely to use formal bins, while university graduates, despite greater environmental awareness, often resorted to burial within their compounds. Middle-income households were more likely to engage in river dumping. These findings suggest that higher socioeconomic status or educational attainment does not automatically translate into more environmentally sound practices, particularly in contexts characterized by inadequate waste infrastructure.

4.5. Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Household Waste Disposal Practices

The multivariate analysis of waste disposal patterns is presented in Table 5. Results indicate Musina Municipality residents are significantly less likely to dispose of waste in bins compared to Makhado (OR = 0.1, 95% CI: 0.02–0.95, p = 0.044), suggesting deficient formal waste collection. The incidence of waste dumping in natural water bodies was high, with residents 141.6 times more likely to engage in this practice (OR = 141.6; 95% CI: 39.5–508.5, p < 0.001), highlighting critical environmental and health concerns. Waste management challenges exist in Collins Chabane Municipality. Residents are significantly less likely to use bins (OR = 0.2, 95% CI: 0.07–0.9, p = 0.029), indicating limited collection services. While dumping in rivers does not differ significantly from Makhado (OR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.08–4.2, p = 0.589), roadside dumping is concerning, with residents 18.2 times more likely to dispose of waste this way (OR = 18.2, 95% CI: 5.3–62.9, p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Adjusted odds ratios from multivariate logistic regression models examining predictors of household waste disposal methods.

The Thulamela Municipality exhibits similar challenges. Although no significant difference was observed in bin usage (OR = 0.4, 95% CI: 0.06–2.9, p = 0.361), the most concerning finding was that residents were 30 times more likely to dispose of waste on roadsides than those in Makhado (OR = 30.0, 95% CI: 8.8–101.9, p < 0.001). This suggests that roadside dumping is a prevalent practice, likely due to the inadequate waste collection infrastructure.

The location of residence plays a crucial role in determining waste disposal behavior. Farm residents were 5.1 times more likely to dump waste in rivers than their rural counterparts (OR = 5.1, 95% CI: 2.8–9.4, p < 0.001), raising environmental concerns regarding water contamination. However, they were significantly less likely to dispose of waste on roadsides (OR = 0.6, 95% CI: 0.01–0.2, p < 0.001), possibly due to the rural nature of their living environment.

In urban areas, particularly city centers, residents exhibited an increased tendency to dispose of waste on roadsides (OR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.0–3.7, p < 0.001), reflecting common urban waste management issues such as illegal dumping due to overflowing bins or irregular waste collection. Township residents displayed a mixed pattern of waste disposal. They were more likely to use bins (OR = 3.9, 95% CI: 0.8–19.4, p = 0.092), suggesting better access to formal waste collection. However, they were also significantly less likely to dump waste in rivers (OR = 0.1, 95% CI: 0.02–0.4, p = 0.003), indicating more environmentally conscious practices than rural or farm areas.

Household income levels have a significant impact on waste disposal practices. Individuals with an income range of ZAR 10,000 to ZAR 30,000 were 19 times more likely to dispose of waste in rivers (OR = 19.0, 95% CI: 7.3–49.5, p < 0.001), indicating that even middle-income households may face challenges in accessing formal waste disposal systems. For those earning between ZAR 30,000 and ZAR 50,000, the propensity for river dumping remained elevated (OR = 12.9, 95% CI: 4.4–38.5, p < 0.001), and these households were also 3.6 times more likely to dispose of waste on roadsides (OR = 3.6, 95% CI: 1.8–7.2, p < 0.001). Notably, higher-income households were significantly less likely to dispose of waste in a hole within their compound (OR = 0.05, 95% CI: 0.02–0.1, p < 0.001), suggesting a preference for alternative waste disposal methods, such as private waste collection services.

The findings underscore that waste disposal behavior is profoundly influenced by geographic location, municipal infrastructure, and income levels. Municipalities such as Musina and Collins Chabane face substantial environmental challenges due to prevalent dumping in rivers and on roadsides. Rural and agricultural areas lack adequate disposal infrastructure, resulting in increased dumping in open spaces and water bodies in these areas. Furthermore, middle-income households demonstrated suboptimal waste disposal behaviors, particularly with high incidences of river dumping.

4.6. Thematic Interpretation of Findings

4.6.1. Service Access and Perceived Behavioral Control (TPB Construct: Perceived Behavioral Control, EJ Dimension: Distributional Justice, SDGs: 11.6, 6.3)

The low percentage (8%) of households utilizing formal waste bins stands in stark contrast to the 92% of households engaging in informal disposal methods. This outcome reflects limited perceived behavioral control within the TPB framework, which does not arise solely from internal volition but is significantly influenced by objective infrastructural constraints. The lack of proximate public bins, with 78.2% of households lacking access within 1 km, exemplifies a critical form of distributional injustice: the material enablers for responsible waste disposal are inequitably allocated to the poor. Multivariate regression analysis confirmed that residents in underserved municipalities, such as Musina (OR = 0.1, p = 0.044), faced disproportionately constrained disposal options. These patterns undermine SDG 11.6, which pertains to sustainable waste management, and SDG 6.3, which concerns water quality, reinforcing the argument that pro-environmental behavior cannot be disentangled from equitable infrastructure provision.

4.6.2. Spatial Disparities and Environmental Injustice (TPB Construct: Subjective Norms, EJ Dimension: Spatial and Procedural Justice, SDGs: 10.2, 11.1)

The spatial distribution of waste management behavior highlights persistent inequities. Residents of urban centers and townships have greater access to formal waste management services; however, they also engage in practices such as roadside dumping, indicating a normalization of deviance from environmental standards in densely populated areas. Conversely, individuals residing in rural areas were over five times more likely to dispose of waste in rivers (OR = 5.1, p < 0.001), which serves as a clear indicator of ecological vulnerability exacerbated by geographic marginalization. These disparities undermine the objectives of SDG 10.2 (inclusion and equity) and 11.1 (universal access to basic services), while underscoring the spatial dimensions of environmental norms and their enforcement in Brazil.

4.6.3. Education, Income, and the Behavior–Infrastructure Paradox (TPB Construct: Attitudes, EJ Dimension: Recognitional Justice, SDGs: 4.7, 12.5)

Contrary to the expectations derived from the TPB, higher levels of educational attainment and income do not uniformly predict sustainable waste disposal practices. Although households with university-educated members were more inclined to bury waste within their compounds (OR = 9.9, p = 0.004), they did not consistently utilize waste bins, revealing a paradox where pro-environmental attitudes were present, yet infrastructural limitations persisted. Furthermore, individuals within the middle-income bracket (ZAR 10,000–50,000) demonstrated a significantly higher likelihood of engaging in river dumping (ORs > 11, p < 0.001), reflecting systemic neglect rather than a lack of environmental concern. This observation highlights the principle of recognitional justice, emphasizing the necessity of acknowledging socio-environmental barriers when interpreting behavioral outcomes. Additionally, it aligns with SDG 4.7, which focuses on education for sustainable development, and 12.5, which aims at waste reduction.

4.6.4. Gender, Age, and the Myth of Individual Choice (TPB Constructs: All, EJ Dimension: Recognitional and Procedural Justice, SDGs: 5.5, 10.2)

The study identified no significant differences in waste disposal practices based on gender, thereby challenging the assumption that women’s traditional roles in household sanitation inherently lead to environmentally conscious behavior. Similarly, older adults exhibited contradictory patterns, with increased bin usage and a higher incidence of river dumping, suggesting that age-based assumptions of environmental responsibility may oversimplify complex realities. These findings question the notion of purely individual choice in environmental behavior, highlighting that structural and procedural inequities influence perceived norms and actual opportunities for pro-environmental behavior. They align with SDG 5.5 (gender equality in decision-making) and 10.2 (social inclusion).

4.6.5. Theoretical Synthesis and Framework Reflection

The findings substantiate the study’s integrated TPB–EJ framework by demonstrating that perceived behavioral control extends beyond a mere cognitive belief and is materially constrained by infrastructural deficiencies and spatial exclusion. The correlations between informal disposal and variables such as settlement type, income, and service access affirm that this behavior is influenced by both individual agency and structural limitations. These results underscore the value of integrating psychological and justice-based models in the analysis of environmental action, particularly within underserved LMIC contexts (see Figure 1).

5. Discussion

This study examined the factors influencing household waste disposal practices in South Africa’s Vhembe District by employing a conceptual framework that integrates the TPB and EJ. By operationalizing perceived behavioral control, subjective norms, and attitudes in conjunction with spatial, procedural, and recognitional inequalities, this study provides a nuanced understanding of informal disposal practices in regions lacking adequate infrastructure. These findings contribute to ongoing global discussions on sustainable waste governance, particularly in rural and peri-urban settings of LMICs and align with the localization agenda of the SDGs.

5.1. Spatial Inequality and Distributional Injustice (TPB: Perceived Behavioural Control, EJ: Distributional Justice, SDG 11.6, 6.3)

The analysis indicated that only 8% of households utilized formal waste bins, whereas over 78% reported a lack of access to bins within a 1 km radius. This spatial disparity was most evident in Musina and Collins Chabane, where it was associated with environmentally detrimental practices such as river dumping (OR = 141.6) and roadside disposal (OR = 18.2). From the perspective of the TPB, limited access constrains perceived behavioral control, thereby undermining the feasibility of normative intentions to engage in responsible waste disposal.

These patterns reflect global studies that demonstrate how geospatial marginality leads to infrastructure exclusion. For instance, in rural China, spatial remoteness predicts household reliance on illegal dumping [42]. Similarly, in the Kibera and Mukuru slums of Kenya, inadequate service coverage correlates with self-managed waste disposal practices [43]. This confirms the concept of distributional injustice as articulated in the EJ theory, where location determines exposure to risk and access to basic services [23].

5.2. Informal Disposal as Structural Adaptation (TPB: Limit of Intentionality, EJ: Structural Constraint, SDG 12.5, 13.1)

Despite established behavioral norms against waste dumping, the study revealed that over 90% of households engaged in informal waste management practices, with 41.4% opting to bury waste within their homes. These actions are indicative of constrained behavioral execution, rather than attitudinal indifference. According to EJ theory, such practices are rational adaptations to systemic neglect rather than deviant behaviors [26,42,44,45].

Similar findings have been reported in Bangladesh, where Tajkir-Uz-Zaman [46] observed that residents without access to municipal waste collection routinely resorted to burning or burying waste. Likewise, in the peri-urban areas of Indonesia, Amir et al. [18] found that informal waste burning persists in the absence of formal infrastructure, despite high levels of environmental awareness. These cases highlight a significant contribution of this study: the TPB alone is inadequate to explain waste management behavior in resource-constrained contexts. The integration of the TPB and EJ frameworks advances behavioral theory by contextualizing “perceived control” within structural realities.

5.3. Socioeconomic Status and Conditional Agency (TPB: Attitudes and Norms, EJ: Recognitional and Procedural Justice, SDGs 10.2, 12.8)

Multivariate analyses revealed intricate socioeconomic gradients. Paradoxically, households with higher incomes were more inclined to engage in river and roadside dumping. This phenomenon may be attributed to increased waste generation rates that are not matched by proportional service provision, a pattern observed in the urbanizing regions of Nigeria [47] and Indonesia [18].

This finding appears to contradict assumptions of the TPB, which links higher socioeconomic status with pro-environmental behavior. However, the elevated river dumping among wealthier households (OR = 19.0) likely reflects persistent infrastructural gaps rather than behavioral deficits. Even in higher-income households, limited access to formal collection, especially in peri-urban and rural areas, can constrain environmentally responsible choices. In this context, perceived behavioral control must be understood not merely as a matter of individual agency but as fundamentally shaped by material and institutional limitations. Moreover, greater consumption among affluent households may amplify disposal pressures, further complicating the feasibility of sustainable behavior.

Education demonstrated a protective effect against environmentally detrimental behaviors, consistent with the findings of Estrada-Araoz et al. [48]. Nonetheless, even university graduates resorted to waste burial (OR = 9.9), highlighting the necessity for recognition of justice that values lived experiences to complement behavioral interventions. This evidence emphasizes that perceived control is not solely an internalized agency but also a function of external constraints, as reconceptualized by the framework, and that awareness of sustainable development (SDG 4.7) alone may be insufficient in the absence of enabling infrastructure.

Gender was not a statistically significant predictor of disposal practices. This finding aligns with the interpretation that structural and service-related constraints affect male- and female-headed households uniformly. In low-service contexts, waste disposal decisions are shaped less by individual demographic attributes and more by shared household adaptations to infrastructural exclusion. Similar patterns have been observed in other LMICs, where gendered behavioral distinctions diminish under widespread service deficits [49,50]

5.4. Settlement Type and Spatial Governance Exclusion (TPB: Subjective Norms (Proxy) EJ: Procedural and Recognitional Justice, SDGs 11.a, 16.7)

Disposal practices are influenced by residential typology. Farm residents were five times more likely to dispose of waste in rivers, whereas township residents exhibited a relatively higher likelihood of utilizing formal waste bins. These findings are consistent with the spatial disparities observed in Accra [51,52] and Dar es Salaam [53], where municipal planning frameworks inadequately serve informal and peri-urban settlements.

This exclusion exemplifies both procedural and recognitional injustice, as these communities are neither involved in planning processes nor represented in institutional priorities [23,42]. From the TPB perspective, social norms within such settlements are shaped not only by cultural values but also by collective adaptations to exclusion. Consequently, this study underscores the necessity of situating subjective norms within local political geography.

5.5. Policy Integration and SDG Alignment (TPB–EJ Interface, Policy Planning, SDGs 11.6, 12.8, 13.1)

This study highlights the necessity of effective waste governance extending beyond mere behavior change messaging, emphasizing the need to address structural and institutional inequities. The key recommendations are detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Key policy recommendations.

5.6. Implementation Challenges and Feasibility Considerations

While Table 6 presents relevant policy recommendations, their implementation faces key challenges, especially in resource-constrained municipalities. Expanding formal waste services requires significant funding, yet many local governments rely heavily on conditional grants and lack sustainable revenue streams. Applying behavioral science to waste policy also demands cross-sector coordination among environmental, education, and communication agencies, which is often weak in fragmented municipal systems. Similarly, decentralizing waste planning is limited by poor community participation mechanisms and a lack of institutional capacity in rural areas.

Reframing environmental messaging to focus on equity assumes largely underdeveloped and culturally responsive communication strategies. Integrating waste management with climate resilience planning requires technical expertise and interdepartmental coordination capacities often absent at the local level. These challenges reflect broader patterns identified by [54], which noted that limited fiscal autonomy and administrative capacity hinder municipal waste reform in sub-Saharan Africa. Addressing these constraints will require targeted investments, institutional reform, and support from national and international actors.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated household waste disposal behaviors in the Vhembe District, South Africa, using an integrated framework that combines the TPB with EJ. By aligning behavioral intent with structural constraints, this study elucidates how socioeconomic status, spatial marginality, and infrastructural exclusion converge to influence waste practices in rural and peri-urban low-resource settings. Unlike most prior research, which applies TPB or EJ independently and primarily in urban, high-service environments, this study addresses a significant empirical gap by operationalizing the TPB–EJ framework in a rural African context, where material deprivation and governance asymmetries render conventional behavioral models insufficient.

The findings indicate that informal and environmentally hazardous disposal methods are not solely a result of individual negligence but rather rational responses to persistent service deficits. Key determinants, such as income, education, residential location, and service access, were found to influence both behavioral choices and environmental outcomes. Importantly, the study reconceptualizes perceived behavioral control as shaped not only by psychological agency but also by material and institutional constraints, thus refining the TPB for low-service contexts.

The integration of TPB and EJ proved analytically robust in linking micro-level behavioral explanations with macro-level spatial and governance inequality. This theoretical synthesis refines behavioral–environmental models and extends the empirical scope of EJ scholarship into under-researched rural African contexts. It also contributes to the localization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by highlighting the roles of distributional, procedural, and recognitional justice. Importantly, the findings underscore recognitional justice by showing that cultural practices and local knowledge significantly shape waste behavior, yet remain absent from formal governance processes

At the policy level, the findings highlight the urgency of decentralized, equity-driven waste governance strategies that are both socially inclusive and contextually grounded. Interventions should prioritize infrastructural investment, community engagement, and the recognition of lived realities in environmental planning. These imperatives are not only aligned with SDGs 11, 12, and 13 but are also essential for achieving climate-resilient and socially just urban transitions in the Global South.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.T. and S.H.; methodology, A.C.T.; software, A.C.T.; validation, A.C.T., S.H., and M.E.L.; formal analysis, A.C.T.; investigation, A.C.T.; resources, S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C.T.; writing—review and editing, S.H. and M.E.L.; visualization, A.C.T. and S.H.; funding acquisition, A.C.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Space Science grant no U371 from the Department of Science and Technology at the Durban University of Technology.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in alignment with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Durban University of Technology (Ethics Clearance Number: IREC 294/22 and 4 July 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Aifani Confidence Tahulela, upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AAMC | Association of American Medical Colleges |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| EJ | Environmental Justice |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MSW | Municipal Solid Waste |

| MWS | Municipal Waste Service |

| OECD | Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| TPB | Theory of Planned Behavior |

| US-EPA | United States Environmental Protection Agency |

References

- Kaza, S.; Yao, L.; Bhada-Tata, P.; Van Woerden, F. What a Waste 2.0: A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050; World Bank Publications: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; ISBN 1464813477. [Google Scholar]

- Lenkiewicz, Z. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Yang, M.; Osman, A.I.; Farghali, M.; Liu, E.; Hassan, D.; et al. Municipal Solid Waste Management Challenges in Developing Regions: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives for Asia and Africa. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 930, 172794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.E.; Nahar, N.; Chowdhury, N.N.; Gazi-Khan, L.; Sayanno, T.K.; Muktadir, M.A.; Haque, M.S. Identification of Recycling Potential of Construction and Demolition Waste: Challenges and Opportunities in the Greater Dhaka Area. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2025, 197, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.C.; Rodic, L.; Scheinberg, A.; Velis, C.A.; Alabaster, G. Comparative Analysis of Solid Waste Management in 20 Cities. Waste Manag. Res. J. Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2012, 30, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood, L.K.; Kapwata, T.; Oelofse, S.; Breetzke, G.; Wright, C.Y. Waste Disposal Practices in Low-Income Settlements of South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2021; United Nations Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 9789210056083. [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey, L.; Oelofse, S. Historical Review of Waste Management and Recycling in South Africa. Resources 2017, 6, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maphanga, T.; Grangxabe, X.S.; Madonsela, B.S. A Meta-Analysis Review of Waste Generation and Collection in Urban Informal Settlements South Africa. Discov. Environ. 2025, 3, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. General Household Survey 2021; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- DEA. South Africa State of Waste Report—First Draft; Department of Environmental Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ingwani, E.; Thynell, M.; Gurure, L.R.; Ekelund, N.G.A.; Gumbo, T.; Schubert, P.; Nel, V. The Impacts of Peri-Urban Expansion on Municipal and Ecosystem Services: Experiences from Makhado Biaba Town, South Africa. Urban Forum 2024, 35, 297–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murei, A.; Mogane, B.; Mothiba, D.P.; Mochware, O.T.W.; Sekgobela, J.M.; Mudau, M.; Musumuvhi, N.; Khabo-Mmekoa, C.M.; Moropeng, R.C.; Momba, M.N.B. Barriers to Water and Sanitation Safety Plans in Rural Areas of South Africa—A Case Study in the Vhembe District, Limpopo Province. Water 2022, 14, 1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Environmental Affairs. National Waste Management Strategy 2020; DEA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- National Environmental Management. National Environmental Management: Waste Act 59 of 2008; DEA: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moeini, B.; Ayubi, E.; Barati, M.; Bashirian, S.; Tapak, L.; Ezzati-Rastgar, K.; Hashemian, M. Effect of Household Interventions on Promoting Waste Segregation Behavior at Source: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, F.; Miru, A.S.; Sabara, E. Urban Household Behavior in Indonesia: Drivers of Zero Waste Participation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Liu, P. Exploring Waste Separation Using an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior: A Comparison between Adults and Children. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1337969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasan, M.Z.; Hasan, A.M.R.; Rabbani, M.G.; Selim, M.A.; Mahmood, S.S. Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of Bangladeshi Urban Slum Dwellers towards COVID-19 Transmission-Prevention: A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS Glob. Public Health 2022, 2, e0001017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knussen, C.; Yule, F. I’m Not in the Habit of Recycling. Environ. Behav. 2008, 40, 683–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G.; Lu, Y.; Pilgram, C. Local Inequities in the Relative Production of and Exposure to Vehicular Air Pollution in Los Angeles. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.00440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G. Environmental Justice: Concepts, Evidence and Politics; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 9780203610671. [Google Scholar]

- EEA. Delivering Justice in Sustainability Transitions; EEA Report No 13/2023; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho, C.; Del Campo, A.G.; de Carvalho Cabral, D. Scales of Inequality: The Role of Spatial Extent in Environmental Justice Analysis. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2022, 221, 104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Environmental Justice; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Emmanouil, C.; Chachami-Chalioti, S.Ε.; Kyzas, G.Z.; Kungolos, A. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Predict Waste Source Separation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 956, 177356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eremionkhale, G.E.; Sekhon, H.; Lazell, J.; Spiteri-Cornish, L. The Role of An Augmented Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) On Recycling Behaviours in Lagos Nigeria. In Proceedings of the 22nd European Conference on Knowledge Management, ECKM 2021, Coventry, UK, 2–3 September 2021; Academic Conferences International Limited: Reading, UK, 2021; pp. 905–914. [Google Scholar]

- Babazadeh, T.; Ranjbaran, S.; Kouzekanani, K.; Abedi Nerbin, S.; Heizomi, H.; Ramazani, M.E. Determinants of Waste Separation Behavior Tabriz, Iran: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior at Health Center. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 985095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.S.; Haque, I.M.M.S.; Kokash, H.A.; Ahmed, S.; Ahsan, M.N. Drivers of Waste Separation Behavior in Urban Bangladesh: Leveraging Social Norms and Environmental Awareness for Circular Economy Success. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 5, 1631–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Mostafavi, A. Collision of Environmental Injustice and Sea Level Rise: Assessment of Risk Inequality in Flood-Induced Pollutant Dispersion from Toxic Sites in Texas. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2301.00312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y. Environmental Justice in Greater Los Angeles: Impacts of Spatial and Ethnic Factors on Residents’ Socioeconomic and Health Status. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US-EPA. Environmental Justice Collaborative Problem-Solving (EJCPS) Project Selections; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- AAMC. Polling on Environmental Justice and Waste Governance: Impact on Disadvantaged Communities; Association of American Medical Colleges: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Akenji, L.; Bengtsson, M.; Hotta, Y.; Kato, M.; Hengesbaugh, M. Policy Responses to Plastic Pollution in Asia. In Plastic Waste and Recycling; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 531–567. [Google Scholar]

- Frantz Schneider, A.; Aanestad, M.; Carvalho, T.C. Exploring Barriers in the Transition toward an Established E-Waste Management System in Brazil: A Multiple-Case Study of the Formal Sector. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urme, S.A.; Radia, M.A.; Alam, R.; Chowdhury, M.U.; Hasan, S.; Ahmed, S.; Sara, H.H.; Islam, M.S.; Jerin, D.T.; Hema, P.S.; et al. Dhaka Landfill Waste Practices: Addressing Urban Pollution and Health Hazards. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 700–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulkipli, F.; Mohd Nopiah, Z.; Jamian, N.H.; Ahmad Basri, N.E.; Jack Kie, C. Sustainable Public Awareness on Solid Waste Management and Environmental Care Using Logistics Regression. J. Kejuruter. 2022, 2, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jou, Y.T.; Mariñas, K.A.; Saflor, C.S.; Bernabe, D.A.; Casuncad, J.R.; Geronimo, K.; Mabbagu, J.; Sales, F.; Verceles, K.A. Assessing the Community Perception in San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, of Proper Waste Disposal: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics South Africa. Mbalo-Briefnew, the Missing Piece of the Puzzle; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Krejcie, R.V.; Morgan, D.W. Determining Sample Size for Research Activities. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1970, 30, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand Malav, L.; Yadav, K.K.; Gupta, N.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, G.K.; Krishnan, S.; Rezania, S.; Kamyab, H.; Pham, Q.B.; Yadav, S.; et al. A Review on Municipal Solid Waste as a Renewable Source for Waste-to-Energy Project in India: Current Practices, Challenges, and Future Opportunities. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirea, E.M.; Omwenga, J.Q. Determinants of Waste Management Programmes on Sustainable Environmental Conservation in Mukuru Slums in Kenya. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Hum. Res. 2023, 1, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strayer, S.; Stoeffler, S.W. The Intersection of Racism and Poverty in the Environment: A Systematic Review for Social Work. Soc. Dev. Issues 2024, 46, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, J. Overcoming the ‘Value-action Gap’ in Environmental Policy: Tensions between National Policy and Local Experience. Local Environ. 1999, 4, 257–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajkir-Uz-Zaman, A.K.M. Bridging Cultures: Lessons from Japan for Improving Rural Household Waste Management in Bangladesh. Int. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Educ. 2024, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afon, A. A Survey of Operational Characteristics, Socioeconomic and Health Effects of Scavenging Activity in Lagos, Nigeria. Waste Manag. Res. J. A Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2012, 30, 664–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada-Araoz, E.G.; Gallegos Ramos, N.A.; Paredes Valverde, Y.; Quispe Herrera, R.; Mori Bazán, J. Examining the Relationship Between Environmental Education and Pro-Environmental Behavior in Regular Basic Education Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeah, C.; Roberts, C.L. Analysis of Barriers and Success Factors Affecting the Adoption of Sustainable Management of Municipal Solid Waste in Nigeria. J. Environ. Manag. 2012, 103, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwangi, W.W.; Kimani, E.; Okong’, G. Retrieved From. Int. J. Res. Sch. Commun. 2021, 4, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lissah, S.Y.; Ayanore, M.A.; Krugu, J.K.; Aberese-Ako, M.; Ruiter, R.A.C. Managing Urban Solid Waste in Ghana: Perspectives and Experiences of Municipal Waste Company Managers and Supervisors in an Urban Municipality. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mudu, P.; Nartey, B.A.; Kanhai, G.; Spadaro, J.V.; Fobil, J. Solid Waste Management and Health in Accra, Ghana; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; ISBN 9789240024250. [Google Scholar]

- Adebayo, K.; Lateefat, M.; Abimbola, M.; Abosede, A.; Afolabi, O.; Olabisi, M. Challenges of Waste Disposal and Management in Peri-Urban Location around Ilorin Metropolis North Central Nigeria. Am. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 7, 17–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Going Granular with Regional and Municipal Fiscal Data OECD Regional Development Studies OECD and EU Countries; OECD: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).