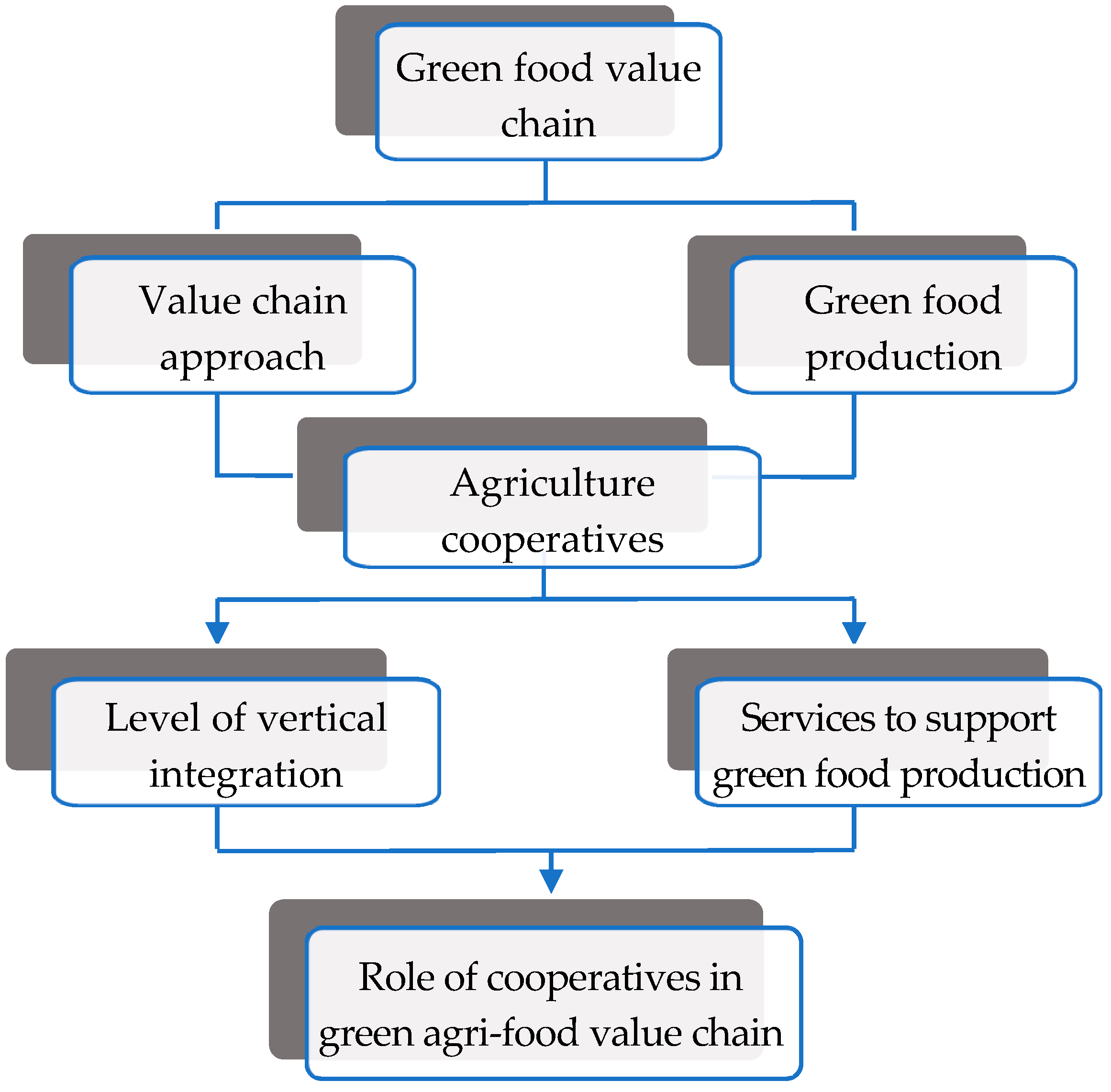

The Role of Agriculture Cooperatives in Green Agri-Food Value Chains in China: Cases in Shandong Province

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Overview of the Cooperatives Studied

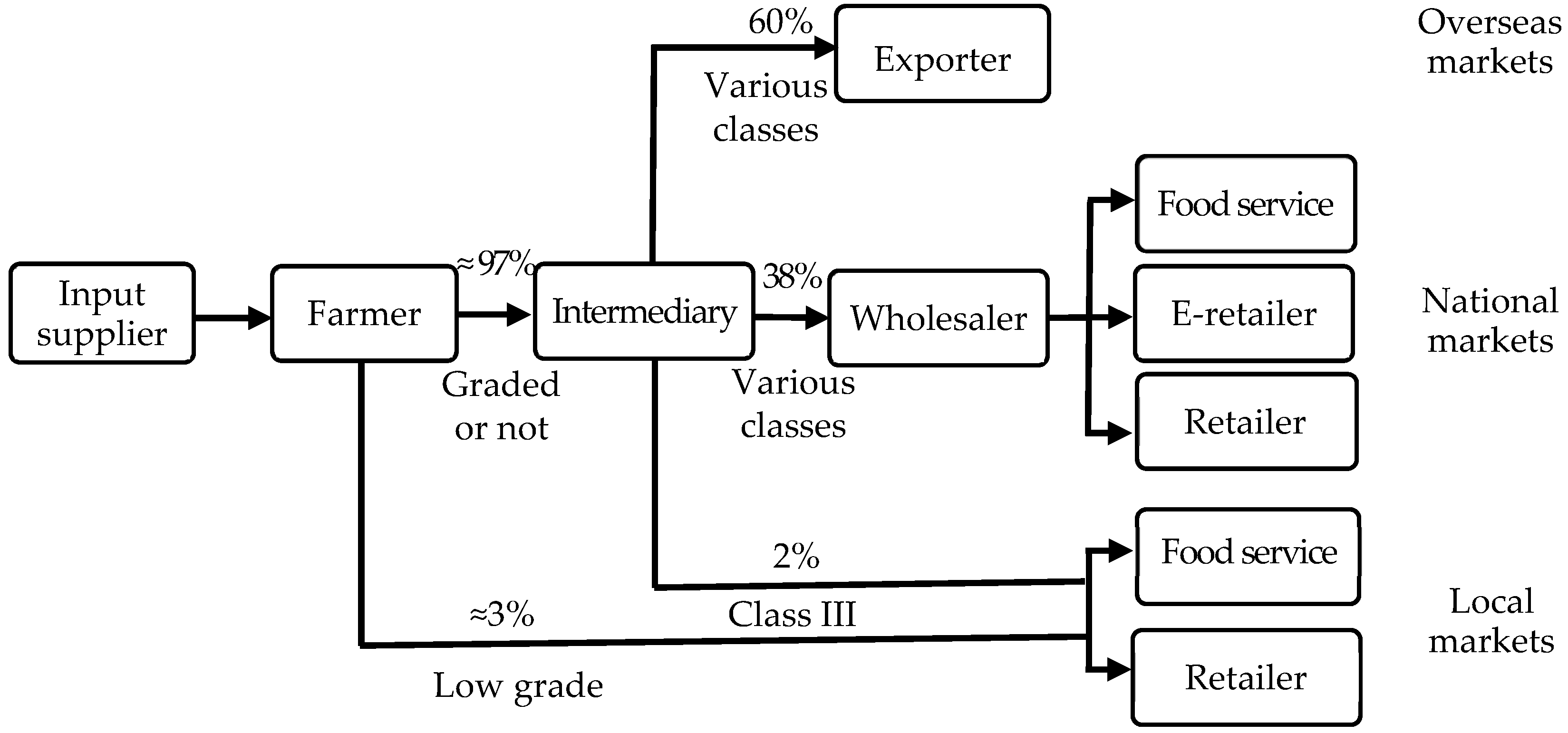

4.2. Green Capsicum Value Chain

4.3. Cooperatives in the Green Capsicum Value Chain

4.4. Support of Cooperatives to Enable Green Agri-Food Production

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ensign, P.C. Value Chain Analysis and Competitive Advantage. J. Gen. Manag. 2001, 27, 18–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fearne, A.; Wagner, B. Value Chain Analysis: A Diagnostic Tool for Building Sustainable Supply Chains. In Handbook of Research Methods for Supply Chain Management, 1st ed.; Childe, S., Soares, A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 368–389. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Developing Sustainable Food Value Chains-Guiding Principles; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Monastyrnaya, E.; Le Bris, G.Y.; Yannou, B.; Petit, G. A Template for Sustainable Food Value Chains. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2017, 20, 461–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, D.R.; Garnevska, E.; Childerhouse, P. Enabling Sustainable Agrifood Value Chain Transformation in Developing Countries. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 395, 136300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.K.; Dey, K. Governance of Agricultural Value Chains: Coordination, Control and Safeguarding. J. Rural. Stud. 2018, 64, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Transforming Food and Agriculture to Achieve the Sdgs: 20 Interconnected Actions to Guide Decision-Makers; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 132. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva, L.; Jayamaha, N.; Garnevska, E. Sustainable Farmer Development for Agri-Food Supply Chains in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayati, R.; Garnevska, E.; Childerhouse, P. Transforming Developing Countries Agrifood Value Chains. Int. J. Food Syst. Dyn. 2021, 12, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, S.; Garnevska, E.; Ramilan, T.; Shadbolt, N. Cooperatives’ Level of Vertical Integration and Farm Financial Performance Amongst Smallholder Farmer-Members in Sri Lanka. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2025, 96, 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chagwiza, C.; Muradian, R.; Ruben, R. Cooperative Membership and Dairy Performance among Smallholders in Ethiopia. Food Pol. 2016, 59, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, H.; Paudel, K.P.; Adhikari, M.; He, Q. Impact of Cooperative Membership on Production Efficiency of Smallholder Goat Farmers in Nepal. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2022, 93, 337–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Renwick, A.; Yuan, P.; Ratna, N. Agricultural Cooperative Membership and Technical Efficiency of Apple Farmers in China: An Analysis Accounting for Selectivity Bias. Food Pol. 2018, 81, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Luo, Q.; Deng, H.; Yan, Y. Opportunities and Challenges of Sustainable Agricultural Development in China. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 893–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veeck, G.; Veeck, A.; Yu, H. Challenges of Agriculture and Food Systems Issues in China and the United States. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.; Zheng, S.; Chen, R. The Influencing Factors and Income Effects of Green Prevention-Control Technology Adoption—An Empirical Analysis Based on the Survey Data of 792 Vegetable Growers. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2022, 30, 1687–1697. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Li, E. A Theoretical Framework and Empirical Analysis of the Formation Mechanism of Green Agricultural Industry Cluster: A Case Study of the Shouguang Vegetable Industry Cluster in Shandong Province. Resour. Sci. 2021, 43, 69–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ul Hassan, M.; Wen, X.; Xu, J.; Zhong, J.; Li, X. Development and Challenges of Green Food in China. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2020, 7, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Ishfaq, M.; Zhong, J.; Li, W.; Zhang, F.; Li, X. Green Food Development in China: Experiences and Challenges. Agriculture 2020, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, Q.F. Alternative Agrifood Systems and the Economic Sustainability of Farmers’ Cooperatives: The Chinese Experience. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 7447–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Garnevska, E.; Shadbolt, N. Organizational Structures of Agriculture Cooperatives in China: Evidence from the Green Vegetable Sector. J. Co-Op. Organ. Manag. 2024, 12, 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Hendrikse, G.; Huang, Z.; Xu, X. Governance Structure of Chinese Farmer Cooperatives: Evidence from Zhejiang Province. Agribusiness 2015, 31, 198–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Y. Institutional Arrangement of Cooperatives: Evolution, Types and Evaluation. Xinjiang State Farms Econ. 2005, 11, 54–59. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Qi, G.; Zhang, Y.; Vernooy, R. Farmer Cooperatives in China: Diverse Pathways to Sustainable Rural Development. Int. J. Agric. Sustain. 2014, 12, 95–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Scott, S. Rural Development Strategies and Government Roles in the Development of Farmers’ Cooperatives in China. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2016, 4, 35–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, Z.; Luo, Y. False Prosperity: Rethinking Government Support for Farmers’ Cooperatives in China. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 94, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Abdulai, A. Does Cooperative Membership Improve Household Welfare? Evidence from Apple Farmers in China. Food Pol. 2016, 58, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zheng, H.; Yuan, P. Impacts of Cooperative Membership on Banana Yield and Risk Exposure: Insights from China. J. Agric. Econ. 2021, 73, 564–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, R.; deVoil, P.; Wan, S. Enhancing the Application of Organic Fertilisers by Members of Agricultural Cooperatives. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 293, 112901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Abdulai, A. Ipm Adoption, Cooperative Membership and Farm Economic Performance: Insight from Apple Farmers in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2019, 11, 218–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Guo, H.; Jia, F. Technological Innovation in Agricultural Co-Operatives in China: Implications for Agro-Food Innovation Policies. Food Pol. 2017, 73, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Chen, C.; Yang, F. A Research of Value Creation and Profit Distribution of Vegetable Supply Chain in Chongqing Based on the Need of Price Management. J. Southwest Univ. 2015, 37, 133–138. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jia, F.; Bijman, J. Vertical Coordination and Cooperative Member Benefits: Case Studies of Four Dairy Farmers’ Cooperatives in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 2266–2277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E. Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; FreePress: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplinsky, R. Globalisation and Unequalisation: What Can Be Learned from Value Chain Analysis? J. Devel. Stud. 2000, 37, 117–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilmi, M. Green Food Value Chain Development: Learning from the Bottom of the Pyramid. Middle East. J. Agric. Res. 2019, 8, 542–560. [Google Scholar]

- Ahi, P.; Searcy, C. A Comparative Literature Analysis of Definitions for Green and Sustainable Supply Chain Management. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 52, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinsky, R.; Morris, M. A Handbook for Value Chain Research; University of Sussex, Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2000; Volume 113. [Google Scholar]

- Hidayati, R.; Garnevska, E.; Childerhouse, P. Sustainable Agrifood Value Chain—Transformation in Developing Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucagna, M.E.; Goldsmith, P.D. Value Adding in the Agri-Food Value Chain. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2018, 21, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.I.; Garnevska, E. Citrus Value Chain (S): A Survey of Pakistan Citrus Industry. Agric. Value Chain. 2018, 37, 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Coltrain, D.; Barton, D.; Boland, M. Value Added: Opportunities and Strategies; Arthur Capper Cooperative Center, Department of Agricultural Economics, Kansas State University: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R.; Gao, Z.; Snell, H.A.; Ma, H. Food Safety Concerns and Consumer Preferences for Food Safety Attributes: Evidence from China. Food Control 2020, 112, 107157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, J.S. Potential for Cooperative Involvement in Vertical Coordination and Value-Added Activities. Agribusiness 1995, 11, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanor-Boadu, V. A Conversation About Value-Added Agriculture; Value-Added Business Development Program, Department of Agricultural Economics, Kansas State University: Manhattan, KS, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fernando, P.S. Value Chain Integration for Rural Co-Operatives: Comparative Analysis in the Rice Sector in Sri Lanka. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, H.C.; Wysocki, A.; Harsh, S.B. Strategic Choice Along the Vertical Coordination Continuum. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2001, 4, 149–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, S.V. Agricultural Cooperatives in France: Toward Environmental Neutrality and Sustainability. In Challenges of the Modern Economy: Digital Technologies, Problems, and Focus Areas of the Sustainable Development of Country and Regions; Buchaev, Y.G., Abdulkadyrov, A.S., Ragulina, J.V., Khachaturyan, A.A., Popkova, E.G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 471–476. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, B.; McCarthy, O.; Byrne, N.; Boland, M.A.; Ward, M. The Role of the Farmer and Their Cooperative in Supply Chain Governance: An Irish Perspective. In Handbook of Research on Cooperatives and Mutuals; Elliott, M.S., Boland, M.A., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; pp. 193–207. [Google Scholar]

- Bijman, J.; Muradian, R.; Cechin, A. Agricultural Cooperatives and Value Chain Coordination. In Value Chains, Social Inclusion, and Economic Development: Contrasting Theories and Realities, 1st ed.; Helmsing, A.H.J., Vellema, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2011; pp. 82–101. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R.; Dent, B. Value Chain Management and Postharvest Handling. In Postharvest Handling: A Systems Approach, 4th ed.; Florkowski, W.J., Banks, N.H., Shewfelt, R.L., Prussia, S.E., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 319–341. [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, J.; Akbar, D.; Rahman, A.; Rajapaksa, D. Can Cooperative Business Models Solve Horizontal and Vertical Coordination Challenges? A Case Study in the Australian Pineapple Industry. J. Co-Op. Organ. Manag. 2022, 10, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, O.E. Transaction-Cost Economics: The Governance of Contractual Relations. J. Law. Econ. 1979, 22, 233–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Xue, C. How Does Risk Management Improve Farmers’ Green Production Level? Organic Fertilizer as an Example. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 946855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannell, D.J. Uncertainty and Adoption of Sustainable Farming Systems In Risk Management and Environment: Agriculture in Perspective; Babcock, B.A., Fraser, R.W., Lekakis, J.N., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Q.; Ma, K.; Liu, W. The Role of Farmer Cooperatives in Promoting Environmentally Sustainable Agricultural Development in China: A Review. Ann. Public Coop. Econ. 2023, 94, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Nilsson, J. Farmers’ Assessments of Their Cooperatives in Economic, Social, and Environmental Terms: An Investigation in Fujian, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2021, 9, 668361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Jin, S.; Wang, H.; Ye, C. Estimating Effects of Cooperative Membership on Farmers’ Safe Production Behaviors: Evidence from Pig Sector in China. Food Pol. 2019, 83, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnevska, E.; Liu, G.; Shadbolt, N. Factors for Successful Development of Farmer Cooperatives in Northwest China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2011, 14, 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Otsuka, K. Impact of Training on the Intensification of Rice Farming: Evidence from Rainfed Areas in Tanzania. Agric. Econ. 2018, 49, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, K.; Muraoka, R.; Otsuka, K. Technology Adoption, Impact, and Extension in Developing Countries’ Agriculture: A Review of the Recent Literature. Agric. Econ. 2020, 51, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Qiao, D.; Tang, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Fu, X. Research on the Influence of Education and Training of Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives on the Willingness of Members to Green Production—Perspectives Based on Time, Method and Content Elements. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 987–1006. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.; Nilsson, J. Social Capital and Financial Capital in Chinese Cooperatives. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wossen, T.; Berger, T.; Di Falco, S. Social Capital, Risk Preference and Adoption of Improved Farm Land Management Practices in Ethiopia. Agric. Econ. 2015, 46, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, C.A.K.; Jayathilake, W.; Wickramasuriya, H.V.A.; Dissanayake, U.; Wasala, W.M.C.B. A Review on Factors Affecting Technology Adoption in Agricultural Sector. J. Agric. Sci. 2022, 17, 280–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, T.; Damodaran, A. Can Cooperatives Influence Farmer’s Decision to Adopt Organic Farming? Agri-Decision Making under Price Volatility. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5718–5742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeiro, V.; Arias, J.; Dürr, J.; Elverdin, P.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Kinengyere, A.; Torero, M. A Scoping Review on Incentives for Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices and Their Outcomes. Nat. Sustain. 2020, 3, 809–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijman, J.; Hu, D. The Rise of New Farmer Cooperatives in China: Evidence from Hubei Province. J. Rural. Coop. 2011, 39, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Ren, J.; Wimmer, S.; Yin, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, C. Incentive Mechanism for Promoting Farmers to Plant Green Manure in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 267, 122197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Li, J.; Mi, Y. Farmers’ Cooperatives and Smallholder Farmers’ Access to Credit: Evidence from China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 92, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, S.; Jiang, Y.; Qiao, S.; Sun, H. Activating the Green Revolution: Farmland Transfer and Agricultural Green Technology Innovation—Evidence from China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, D. Farmers Are Growing Further and Further from the Land: Land Transfer and the Practice of Three Rights Separation in China. Soc. Sci. China 2021, 42, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Deng, H.; Xu, Z. Service Functions and Influencing Factors of Farmers’ Specialized Cooperative Economic Organizations in China. Manag. World 2010, 26, 75–81. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Ma, X.; Wei, G.; Kong, X. The Future of Agriculture: Obstacles and Improvement Measures for Chinese Cooperatives to Achieve Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2023, 15, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Cao, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, E. Viability, Government Support and the Service Function of Farmer Professional Cooperatives—Evidence from 487 Cooperatives in 13 Cities in Heilongjiang, China. Agriculture 2024, 14, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QY Research. Global Capsicum Industry Research Report, Growth Trends and Competitive Analysis 2024–2030; QY Research: City of Industry, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. On-the-Spot Investigation of the Shouguang Vegetable Expo: How the ‘Home of Vegetables’ Can Reach New Heights. Securities Times, 10 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Creswell, J.D. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 5th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: Oxford, MS, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cartwright, L. Using Thematic Analysis in Social Work Research: Barriers to Recruitment and Issues of Confidentiality; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, C.; Liu, S.; Van Grinsven, H.; Reis, S.; Jin, S.; Liu, H.; Gu, B. The Impact of Farm Size on Agricultural Sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 357–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidogeza, J.; Berentsen, P.; De Graaff, J.; Oude Lansink, A. A Typology of Farm Households for the Umutara Province in Rwanda. Food Secur. 2009, 1, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X. Study of the Influence of Cooperative on the Safe Production Behavior of Apple Farmers. Ph.D. Thesis, Northwest A&F University, Xianyang, China, 2020. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

| Cooperative A | Cooperative B | Cooperative C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key founders | Former vegetable traders | Village party branch | Village party branch |

| Year of establishment | 2012 | 2008 | 2014 |

| Year starting green production | 2014 | 2008 | 2016 |

| Current number of members | 102 | 375 | 165 |

| Land size (mu) | 1000 | 4486 | 1500 |

| Number of greenhouses | 312 | 640 | 360 |

| Percentage of capsicum in terms of production volume | 60% | 90% | 10% |

| Percentage of capsicum exported in terms of volume | 60% | 60% | 80% |

| Level of exemplary cooperative | National | National | National |

| Main activities | Greenhouse leasing Collective marketing Transportation | Facilitating the sales of products Loan service | Input supply Collective marketing Loan service |

| Certification | Green certification by CGFDC (2020) | Green certification by CGFDC (2013) | Global GAP and China GAP by CQC (2022) |

| Practices | Cooperative A | Cooperative B | Cooperative C | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input support | Land | Directly leasing land from farmers | Facilitating land use rights transfer | Facilitating land use rights transfer |

| Credit input | Leasing greenhouses to members | Providing loans for greenhouse construction Providing financial support as working capital | Providing loans for greenhouse construction Providing financial support as working capital | |

| Technology | Facilitating the installation of drip irrigation and fertigation systems | Facilitating the installation of drip irrigation and fertigation systems | Facilitating the installation of drip irrigation and fertigation systems | |

| Infrastructure | Developing electricity system | Improving road condition | ||

| Material input | Having one long-term partner supplying inputs at lower prices | Selling inputs to members at lower prices | ||

| Technical support | Training | Used to provide | Periodically provide | Periodically provide |

| Technical assistance | Employing professional technical staff | Employing professional technical staff | Employing professional technical staff Inviting external experts for on-site guidance | |

| Market support | Securing product sales | Mandatory purchasing of members’ products | Facilitating transactions between members and buyers; | Mandatory purchasing of members’ products |

| Long-term cooperation with buyers Extending to other value chain stages | Long-term cooperation with buyers | Long-term cooperation or contract with buyers Extending to other value chain stages | ||

| Economic incentives | Paying 20–30 percent more than non-green products | Paying 20–30 percent more than non-green products | Paying 20–30 percent more than non-green products | |

| Additional 40 cents per kilo for consistent high-grade products | Members obtaining wholesale price | Only purchasing high-grade products and paying an additional 40 cents per kilo | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Garnevska, E.; Shadbolt, N. The Role of Agriculture Cooperatives in Green Agri-Food Value Chains in China: Cases in Shandong Province. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167343

Liu Y, Garnevska E, Shadbolt N. The Role of Agriculture Cooperatives in Green Agri-Food Value Chains in China: Cases in Shandong Province. Sustainability. 2025; 17(16):7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167343

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yan, Elena Garnevska, and Nicola Shadbolt. 2025. "The Role of Agriculture Cooperatives in Green Agri-Food Value Chains in China: Cases in Shandong Province" Sustainability 17, no. 16: 7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167343

APA StyleLiu, Y., Garnevska, E., & Shadbolt, N. (2025). The Role of Agriculture Cooperatives in Green Agri-Food Value Chains in China: Cases in Shandong Province. Sustainability, 17(16), 7343. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17167343