1. Introduction

Urban green spaces represent an environment for exploration and have the capacity to offer the means for reconnection with nature within the city [

1,

2]. Enhancing and showcasing these spaces can become an action involving community engagement and participatory planning, aimed at delivering multidimensional benefits [

3]. Aspects such as human-nature interaction, public health, social inclusion, the definition of a lifestyle, and alternative learning are key drivers in the search for sustainable solutions to enhance and utilize urban green areas [

4,

5]. Such solutions may differ in terms of intervention typologies, choice of construction materials, architectural strategies, and most importantly, their contribution to social sustainability, as reflected in the communities they aim to support [

4,

6]

The development of urban green infrastructure networks serves as a support system for maintaining biodiversity in urban environments, directly impacts quality of life, and fosters local community cohesion [

7,

8,

9]. Contemporary urban living no longer ensures equitable access to adequate green spaces for all residents, limiting opportunities for both active and passive engagement with natural elements. This highlights the urgent need to identify inclusive strategies and design opportunities for developing urban green infrastructure that facilitates access to biodiversity and contributes to enhancing overall quality of life [

10,

11].

In this context, architecture plays a significant role in shaping the character of urban green spaces. However, the architect’s role extends beyond that of a mere creator, encompassing that of a mediator and spatial agent who operates within complex spatial, social, cultural, and political contexts [

12]. The mode of operation may involve either permanent projects or temporary interventions aimed at various forms of activation, often producing acupunctural effects within the urban landscape [

13,

14]. Among these interventions, temporary architecture stands out due to its experimental character and limited lifespan. As types of architectures, the element that distinguishes temporary architectural installations from long-term architecture with an indefinite lifespan is their experimental nature, which aims to observe and provoke user responsiveness to the physical architectural object [

15]. As presented in the comparative study on the formative period of temporary urban interventions and current tendencies [

16], temporary interventions may have either a defined or undefined lifespan, with a focus on activating urban or natural spaces for purposes such as enhancing meaning, assigning new perceptions to places, experimentation, event-based use, community engagement, and landscape discovery. Moreover, the temporary nature of an architectural intervention has the potential to initiate small-scale changes that cumulatively lead to incremental transformation [

17], to act as a strategy for the enhancement of place-based attractiveness [

18], or to act as catalysts for social interaction, urban revitalization, and ecological sensitivity [

19].

This study aims to analyze and document the implementation of a project involving temporary architectural intervention in a predominantly natural urban environment, with the goal of facilitating human–nature interactions and fostering mutual enhancement between the two. Furthermore, the paper critically engages with bottom-up methods for defining architectural design briefs, emphasizing both the importance and the potential of reusing construction materials to minimize environmental impact. It explores strategies that ensure the reversibility of interventions while also considering their effects during the period of use. Furthermore, it highlights the educational value of temporary interventions within non-formal learning processes and their contribution to community cohesion—understood as a fundamental objective in achieving social sustainability [

4,

20]. Although the case study presents certain specificities and advantages—such as the flexibility of being situated on privately owned land—what makes it valuable and positions it as a good practice example is its openness to public use. It becomes integrated into the broader ecosystem of both the natural and anthropized urban context. The study also addresses the potential of private initiatives in activating urban green areas, which may lead to the formation of public–private partnerships aimed at improving urban quality of life, fostering social interaction, and establishing an infrastructure for non-formal learning and harmonious cohabitation with local biodiversity. In conclusion, this case highlights the transformative potential of temporary, community-oriented, and privately initiated interventions as drivers of inclusive, sustainable, and community-centered urban development.

2. Background

2.1. Temporary Architecture as Urban Acupuncture

When addressing urban landscapes—regardless of their level of densification—interventions function as hotspots that facilitate interactions between people and the landscape and experiential learning. The insertion of new elements into the urban space can produce three types of phenomenological effects: anticipated effects, spontaneous effects, and memory-related effects that reset or complete the identity of the place [

21,

22,

23].

Anticipated effects are defined through the design brief—they represent the project’s stated goals and act as a driving force for implementation. On the other hand, spontaneous effects refer to outcomes not originally envisioned in the design process. Depending on the context, these can be positive (e.g., extensive involvement of local communities or external stakeholders in the implementation and use of the intervention) or negative (e.g., resistance or lack of acceptance by local communities or other users). In such cases, the causes often lie in the lack of contextualization or the failure to adequately consult those directly affected by the proposed intervention. The third category—memory effects—refers to the capacity of architecture to incorporate, preserve, express, and transmit emotions or socio-cultural and historical meanings, while also having the potential to redefine local identities, memories, and attachments [

24,

25,

26,

27]. In the case of temporary architecture, despite its limited lifespan, these memory effects can be especially profound due to the intensity and immediacy of user interaction. The value of the intervention lies in the acupuncture-like effect, which can be understood as generating activation or reactivation processes, attributing new meaning to a place through the definition of a renewed local specificity, or producing incremental, phased effects that unfold over time as part of a staged development process.

2.2. Discussion on Small-Scale Architectural Installations—Design, Workflow, Material Reuse, Reversibility

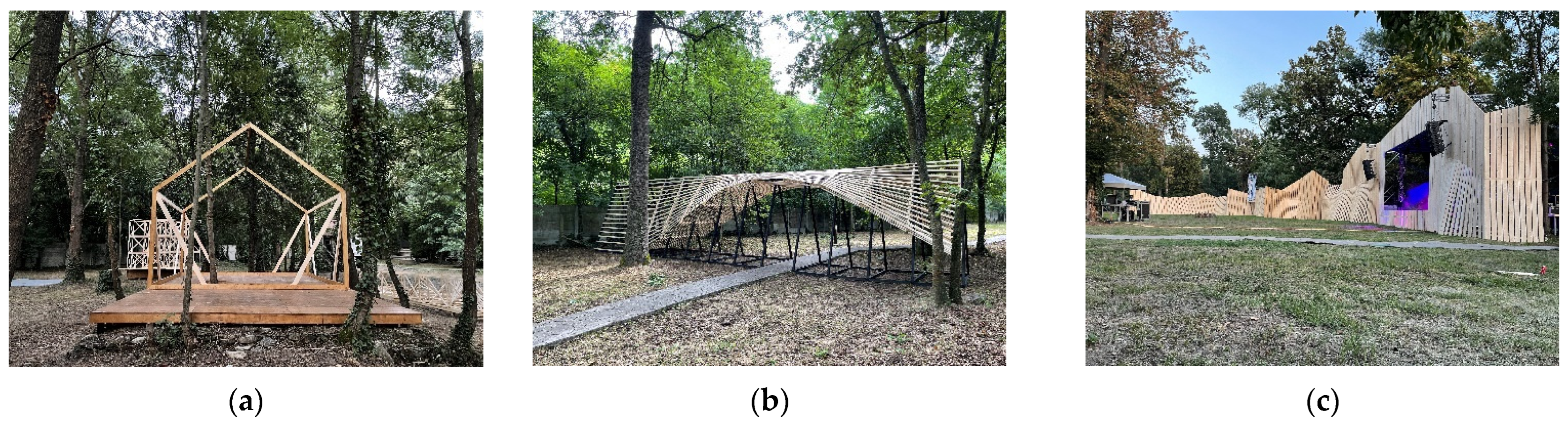

From the perspective of the creation of temporary architectural elements, these can take various forms and scales and may be designed with diverse intended lifespans—ranging from a few days to several years. In each case, however, the process is inherently circular—encompassing design and construction, followed by dismantling with material recovery and reuse, or repurposing—through which architectural installations respond to a specific set of needs at a given moment in time. This approach has been exemplified by structures previously implemented in the urban landscape of Timișoara, Romania, as seen in

Figure 1. These installations reflect different responses to the same context—the site of the Banat Village Museum, which served as the venue for the Plai Festival. In all three cases, the design brief was identical: to facilitate access to the museum grounds through a temporary installation that mediates the dialogue between the existing context and the character of the event, which focuses on local cultural actors and world music programming. The three examples illustrate distinct forms of user interaction:

Figure 1 features (a) a multidirectional tunnel, (b) a unidirectional tunnel, and (c) a modular wall. The user experiences vary according to the architectural configuration of each installation and its spatial relationship to the museum’s entrance, while also showcasing methods of working with reusable materials and context-specific components. These were implemented using simple construction techniques, yet resulted in final products that reflect alternative, reversible forms of architecture, guided by the “leave no trace” principle within the whole process of design, build and disassembly [

28,

29].

On the other hand, event-based interventions follow the same design logic and workflow principles, but with different intentions.

Figure 2 presents additional case studies developed within the same festival framework, yet each with distinct conceptual aims. Image (a) illustrates a skeletal temporary structure that proposes a minimal reconstruction of a windmill silhouette, placed atop the original stone foundation, as a gesture of architectural remembrance—an attempt to reintegrate an absent structure into the collective memory. Image (b) presents a gateway that reinterprets elements of traditional architecture, while image (c) depicts a larger-scale installation that defines a central gathering area for festival participants. This element integrates multiple functions, including a performance stage, a transitional bridge between subzones, and markers for culturally themed projects.

The examples from previous projects underscore the capacity of small-scale temporary architectures to respond not only to specific functional needs but also to phenomenological dimensions—evoking emotional responses and reinforcing a sense of place. Regarding construction methods and implementation, the presented examples demonstrate reversible characteristics and minimal impact on the existing context, which is regarded as a natural and heritage-valued landscape. In this sense, ephemeral architectures are emphasized for their ability to create meaningful experiences, to function as experimental and prototypical modes of operation, and to provide opportunities for non-formal learning—whether through direct involvement in the building process or through simple on-site interaction.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Top-Up vs. Bottom-Down

The definition of the design method and intervention approach in a context where the spatial character is already established can vary depending on the project’s goals [

12]. It may follow a top-down approach, in which a general vision or overarching image is established first and then dictates the development of its individual components. Alternatively, it can adopt a bottom-up approach, which begins with a series of input variables that gradually converge into a coherent outcome.

In the case of temporary architecture, the bottom-up approach is more commonly encountered [

30]. It typically begins with the identification of a set of needs—functional, social, cultural, aesthetic, and semantic. For interventions in public or semi-public spaces, contextual analysis plays a crucial role in outlining and defining these needs, which may vary across short-, medium-, or long-term horizons. The bottom-up approach relies on identifying real, context-specific needs to which the architectural object seeks to respond, using these needs as the foundation for formulating the design brief.

For urban green spaces, in addition to the social context and patterns of human use and interaction with the space, a key conditioning factor is the existing biodiversity. This requires careful analysis to determine how biodiversity can coexist with human presence in a way that supports mutual enhancement of both ecological and human systems.

3.2. The Garden of Impermanence Project—A Case Study

3.2.1. Urban and Green Environment Context

The project presented in this paper is titled The Garden of Impermanence. It was developed as part of the Future Divercities program, coordinated in Timișoara, Romania, by the Plai Cultural Center. This initiative investigates the potential of architecture to meaningfully and sustainably enhance the role of a community-oriented urban garden that is privately owned, expanding its social and spatial possibilities.

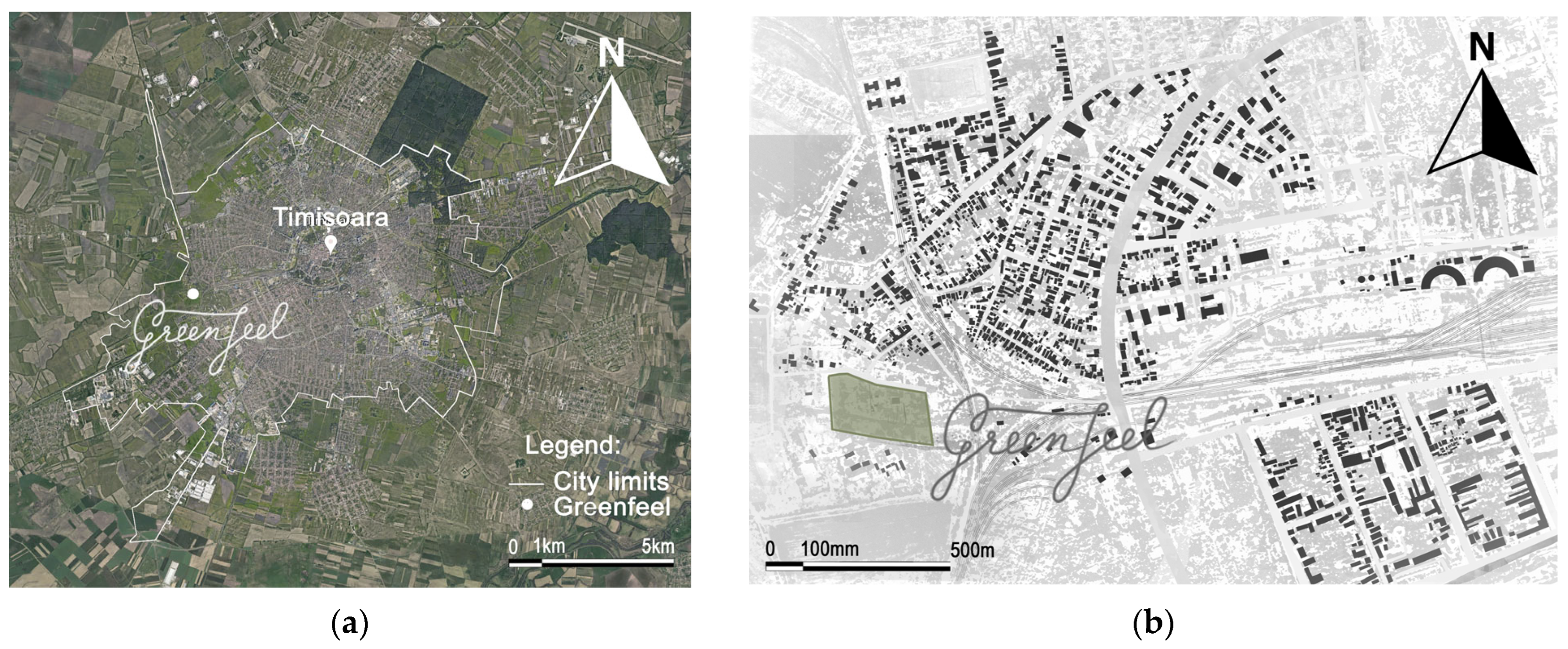

The intervention is located in the western part of the city of Timisoara at the border between a residential neighborhood (to the north in the aerial view) and the city’s green periphery, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

From a social and functional standpoint, the site called Greenfeel functions as an urban garden that fosters community engagement. It features shared gardening plots, open-air gathering spaces, and hosts a diverse range of events, workshops, and hands-on activities. These activities span themes such as ecological education, natural building techniques, sustainable gardening, and civil society support [

31]. Distributed across its expansive green site are various spatial interventions (

Figure 4)—including individual gardening plots, outdoor activity areas, a permanent residential structure, small ponds, and zones of densely spontaneous vegetation, which together support a rich and diverse ecosystem.

The importance of acknowledging on-site biodiversity lies in its role in defining the character of the environment and its contribution to the experience of navigating and using the surrounding space. Currently, even though the specialized literature continues to explore the connection between biodiversity and health outcomes for urban residents—particularly in terms of its beneficial impact [

32]—the documentation and inventory of plant and animal species has proven essential in establishing the natural identity of the Greenfeel site.

Upon closer, micro-level observation, one can identify a wide variety of plant and animal species inhabiting the area—including insects such as bees and beetles, fish, snails, and other small fauna. This rich repertoire of biodiversity coexists harmoniously with the previously described human-made interventions, contributing to a well-balanced and resilient ecosystem as seen in

Figure 5.

3.2.2. Identifying the Needs, Defining the Assignment and the Design Process

The project began with a clearly defined mission and objectives, which ultimately shaped its conceptual direction. As a bottom-up approach to the project, aimed at accurately grounding it in the real needs of the beneficiaries—which guided the definition of its mission and objectives—informal meetings were held with community members and landowners, as well as discussions with members of the Future Divercities project. The purpose of these meetings was to identify how the project addresses a set of actual needs and how it can serve as a good practice example of temporary architecture and its positive effects on both the community and the existing ecosystem. At its core, the aim was to design and construct a pavilion—an architectural intervention intended to bring the community together by providing space for workshops, collective events, and hands-on learning. The pavilion was conceived not merely as a shelter but as a platform for knowledge exchange, with a thematic focus on urban gardening, ecology, and sustainability. It would serve as a space for dialogue between people and nature, blending into the landscape and coexisting respectfully with the site’s existing flora and fauna.

From a functional standpoint, the structure needed to provide basic protection from the elements—namely rain and sun—while embodying the principles of reversible and temporary architecture. This necessitated design strategies that prioritized material recovery and reuse. These principles framed our ideation process, beginning with a central question: How can we build something that respects and preserves the existing ecological context while fulfilling human needs?

This inquiry launched a search for design solutions, often guided by insights drawn directly from nature. As Janine Benyus notes in her work on biomimicry, nature offers a set of strategies from which we can learn and apply to human systems, including architecture [

33]. One particularly resonant image during our process was that of a bird sheltering its young—wings outstretched, forming a protective, yet open and permeable enclosure. This metaphor came to define the kind of space we envisioned: sheltering but not enclosed, defined but not rigid.

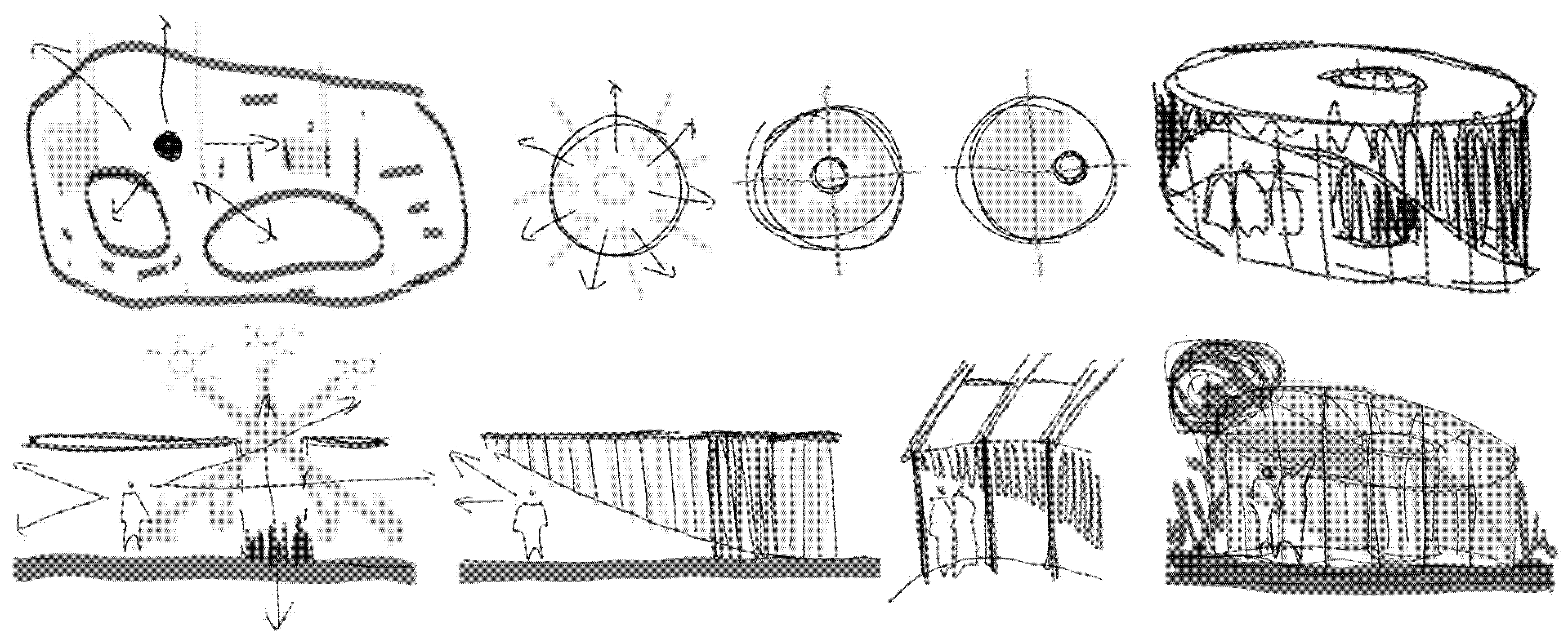

Considering the site’s characteristics, the importance of maintaining visual and physical continuity with the surrounding environment was also recognized. This led to the adoption of a circular layout for the pavilion—an inclusive geometry with no predetermined front, back, or sides, allowing multi-directional access and natural integration with the landscape as seen in

Figure 6. The choice of a circular layout, which implies multidirectionality and does not encourage perceptual hierarchies, can be a replicable approach in various urban contexts, within the spatial possibilities, particularly when the design brief aims to define focal points or spaces that promote social inclusion. Such spaces can function as facilitators of social interaction, dedicated to information exchange, exhibitions, or as community hubs. An example of this type of temporary architecture is the A Table project, developed by AAA for the Concentrico 08 Festival (2022), which proposed a large table as a social cohesion activator [

34].

This was followed by the question: How can this structure offer visitors a microcosmic experience of the broader green environment?

This question inspired the integration of a central green core—an internal garden that mirrors the surrounding ecosystem. Early design proposals included the addition of a small pond to enhance biodiversity, but the final concept opted for a simple vegetated core—an ecologically sensitive gesture that still evoked and sustained meaningful natural connection.

The rendering functioned as a tool to examine the spatial relationship between the scale of the proposed intervention and the surrounding landscape. It also provided a basis for site-specific analysis, guiding discussions on the optimal placement of this form of architectural “acupuncture”, as seen in

Figure 7.

An initial location was considered near the beehives—visible in the lower right quadrant of the rendering—due to the symbolic connection with biodiversity. However, upon further evaluation, considerations related to accessibility and programmatic coherence led us to relocate the pavilion closer to existing community-oriented interventions. This placement enhances its role as a complementary structure, reinforcing and supporting ongoing social and educational activities within that area of the site. The absence of nearby permanent built structures ensured that the placement of the pavilion would not disrupt existing spatial dynamics nor be visually or functionally obstructed by other elements.

This small-scale intervention was conceived as a form of green landscape acupuncture, with the potential to function as a spatial reference point—a social anchor—within the GreenFeel urban garden.

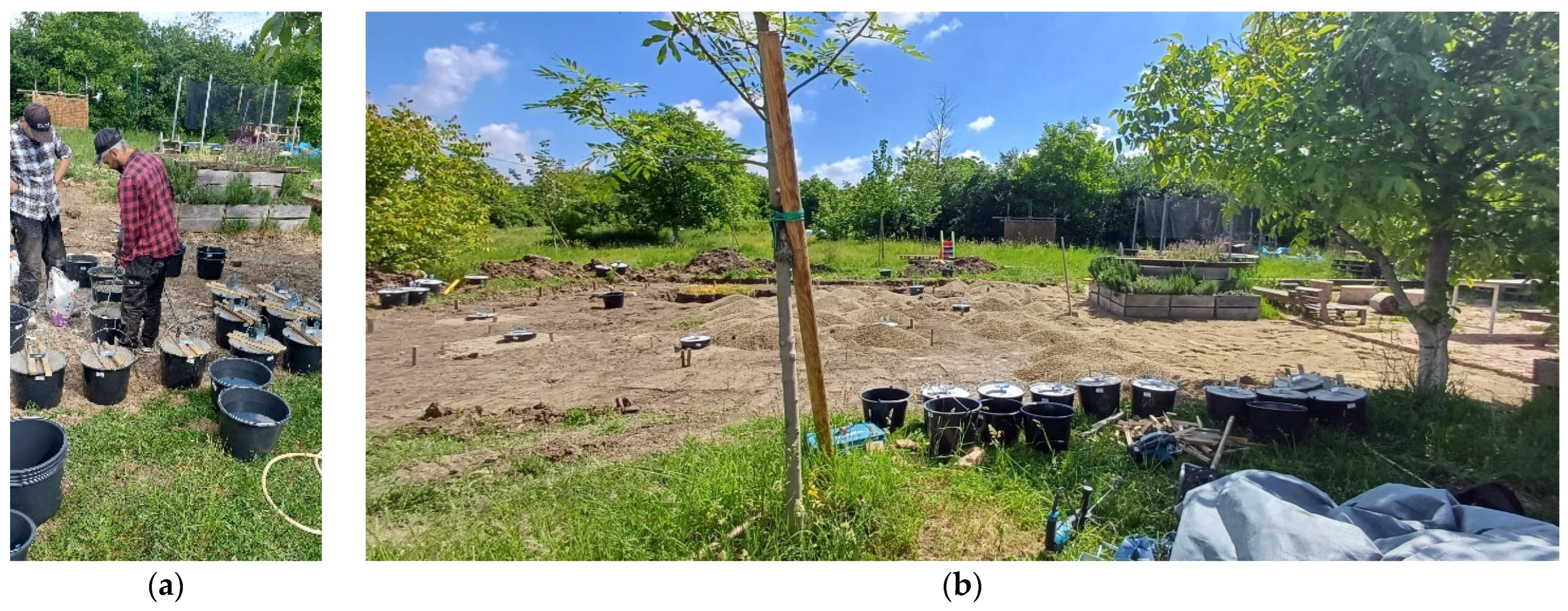

3.2.3. The Process

To ensure reversibility, the foundation system employed a low-impact strategy involving concrete poured into movable containers and the use of metal connectors for securing the wooden structural posts, as seen in

Figure 8. This technique not only facilitated straightforward assembly but also enabled the pavilion’s future disassembly with minimal disruption to the site, thus aligning with the “leave no trace” principle.

The site already featured a pre-existing brick floor, which provided an opportunity for seamless integration with the new intervention. This decision also informed the extension of the existing brick flooring, which was expanded using reclaimed materials as both a practical solution and a symbolic act of continuity and resource consciousness, as seen in

Figure 9. In terms of design, the floor extends the linear brick pattern of the original surface but transitions into a circular layout within the pavilion’s footprint (

Figure 9b).

This shift subtly delineates the spatial enclosure while maintaining visual openness and avoiding rigid physical boundaries. This approach allows, in the event of the structure’s dismantling, for the floor to be retained so that the memory of the intervention can be preserved through the circular brick imprint.

From the outset, the project was guided by a commitment to sustainability, particularly through the reuse of materials. The primary construction material—timber elements recovered from a previous project—shaped both the design approach and the material sourcing strategy, as illustrated in

Figure 10.

3.2.4. Temporarity

The reuse of materials is a common practice within the circular economy, where wood transitions from the status of construction waste to raw material for new projects. An example in this regard is the Material Circle project, coordinated by Prof. Giovanni Betti together with a team of architecture students from the Berlin University of the Arts. It stands as a good practice case for encouraging creative approaches through the reuse of recovered materials, where the entire design process (form, dimensions, structure) is dictated by the available existing material [

35]. In the case of temporary architectures in urban contexts, the recovery and reuse of materials can be carried out with the involvement of the community in the outsourcing process. Moreover, to ensure material circularity, the design process should consider the “afterlife” of materials—how and where they could be reused over time. This requires the formulation of a reuse and waste-reduction strategy developed in parallel with the design phase [

36].

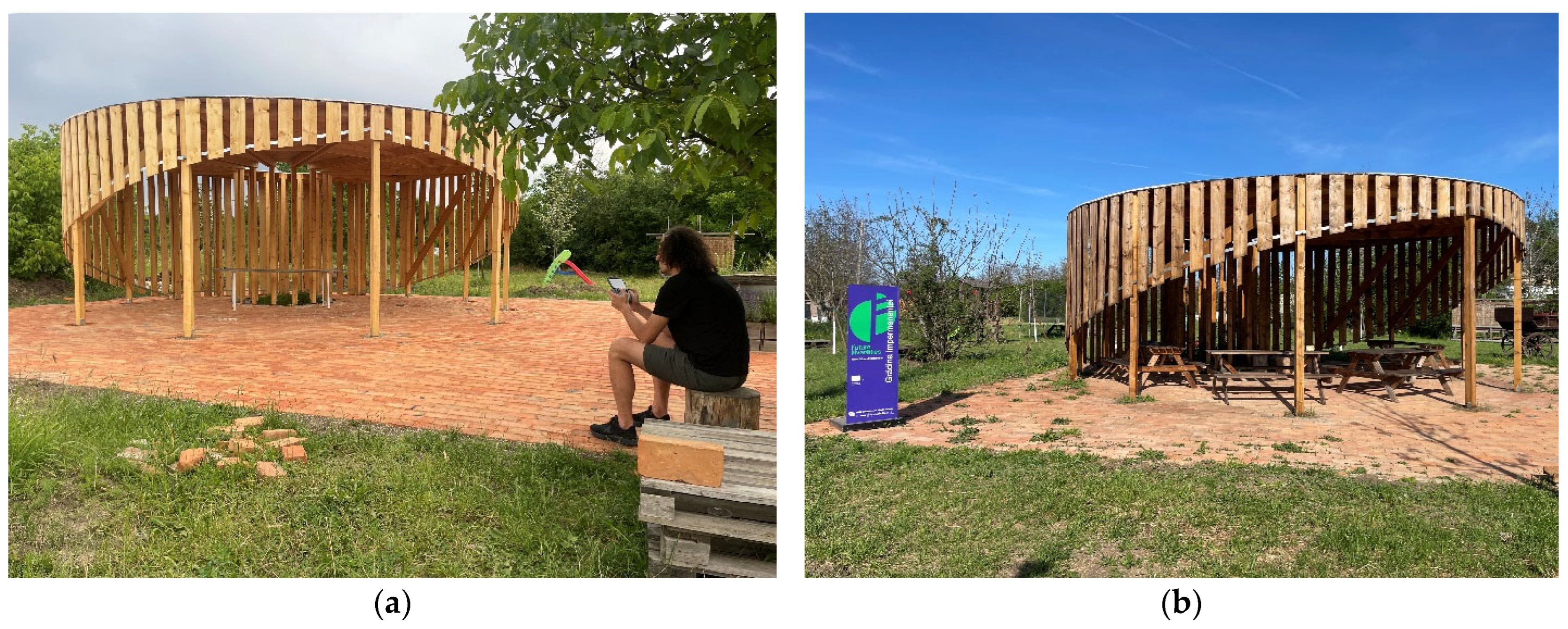

Captured nearly a year apart, the comparative images in

Figure 11 illustrate a structure that, in our assessment, has undergone a graceful process of weathering. We anticipate that, over time, the materials will continue to age, taking on a natural patina—particularly a soft grey hue—that will further integrate the pavilion into its surrounding landscape.

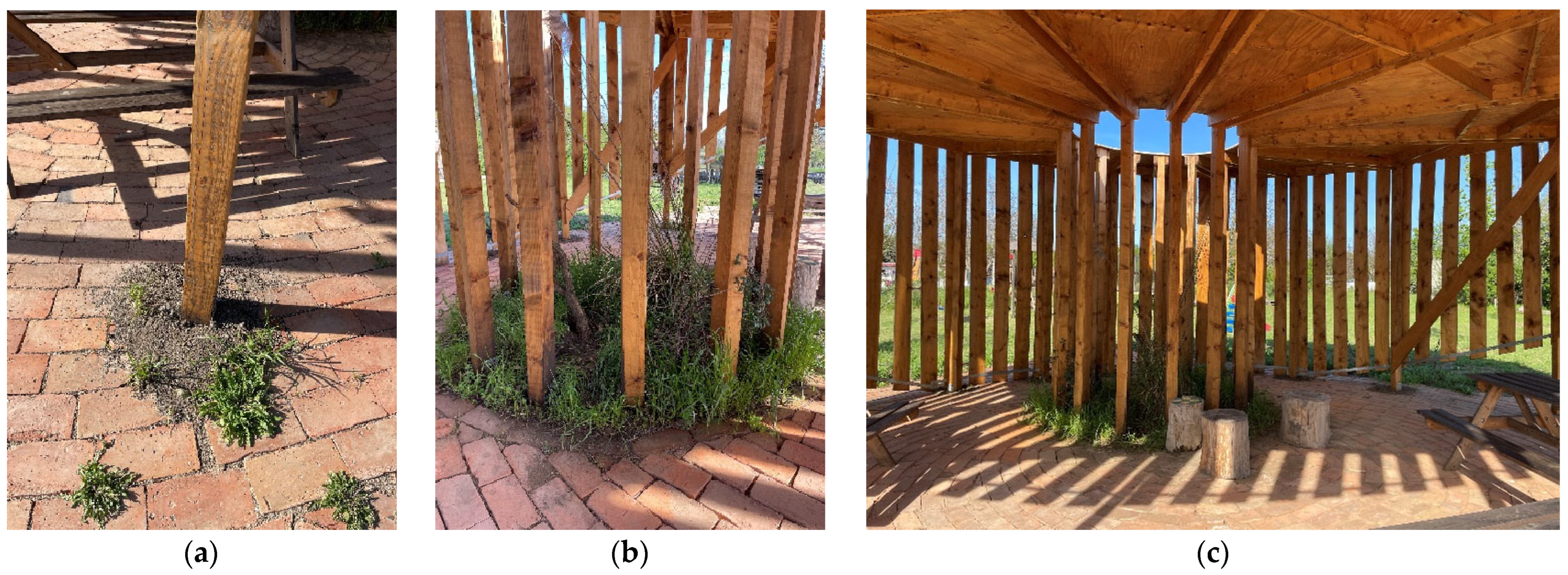

Recently, an encouraging development was observed: grass has begun to grow around the base of the structural elements and between the bricks. This subtle but meaningful change suggests that the intervention is being gradually absorbed into the site’s ecological fabric—a sign of emerging synergy between the built structure and the natural environment, as seen in

Figure 12.

The images in

Figure 13 stand out as a symbolic representation of the project’s ethos. They evoke a parallel with the Pantheon in Rome, where the oculus serves as a dynamic mediator between architecture and the sky through natural light and as a connector between earth and sky in a symbolic manner [

37]. On sunny days, it produces a shifting illumination that accentuates different interior elements depending on the sun’s position. Similarly, in our intervention, the play of light functions as a temporal marker—an experiential reminder of the passage of time, the significance of the present moment, and, by extension, the subtle yet lasting impact of human interventions within a natural or built context.

3.2.5. Community Engagement Towards Social Sustainability—Learning and Exchanging Knowledge and Ideas Through Non-Formal Learning Experiences

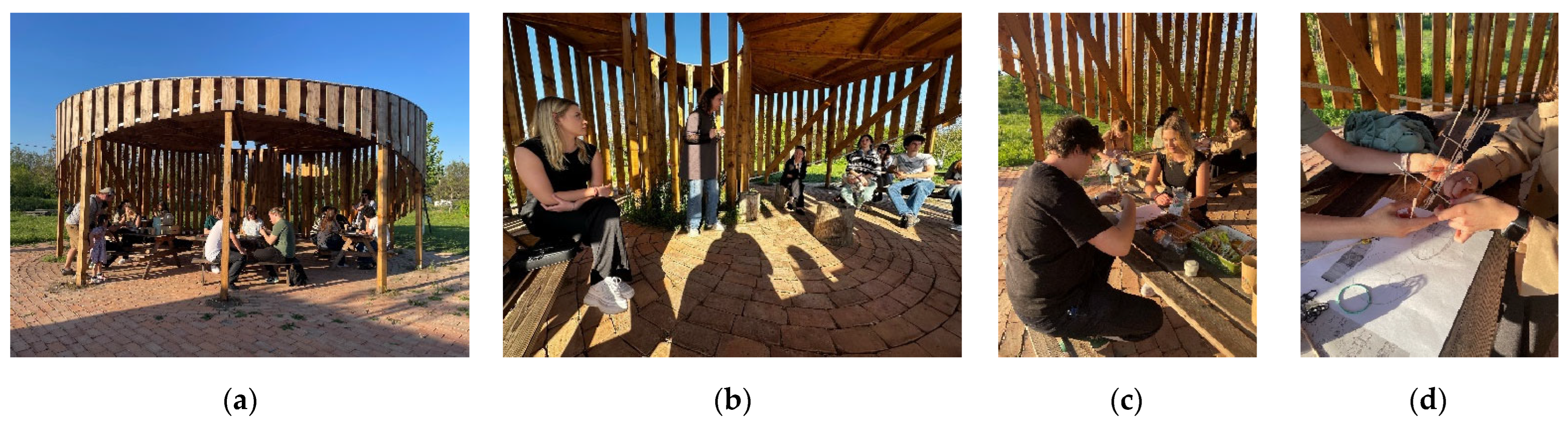

Arguably, the most important phase of the project begins only after a physical completion—when its long-term impact can be assessed in relation to its original objectives.

Since its completion, the Garden of Impermanence pavilion has supported a range of community-driven activities and educational workshops, including a beekeeping session led by Lucian Avramescu (see

Figure 14) and a workshop on the topic of design thinking and model prototyping.

Occurring outside traditional educational institutions, non-formal learning plays a vital role in shaping lifelong competencies that are transferable across contexts. Unlike formal education—structured around standardized curricula, formal assessments, and hierarchical relationships—non-formal education is characterized by voluntary participation, contextual flexibility, and experiential engagement. It emphasizes process over product, empowering learners to take ownership of their development through active, collaborative exploration [

38,

39,

40]. Such educational settings are particularly effective in fostering skills related to sustainability, systems thinking, spatial awareness, and civic engagement. In architecture and urban design, fields where real-world complexity meets creative exploration, non-formal learning allows direct engagement with materials, space, and social dynamics. This educational mode is particularly relevant in fields like architecture and urban design, where spatial complexity, environmental awareness, and community engagement intersect. Temporary architectural interventions often provide ideal settings for non-formal learning by enabling open-ended, participatory experiences outside the constraints of institutional systems [

29,

41,

42].

A representative example was the outdoor workshop on design thinking and form-finding explorations, which served as a sample of a non-formal studio class. This activity was part of the program Volunteering Academy developed by Plai Cultural Center. During this event, participants ranging from ages 13 to 30, working in teams of 3–4 people, had to develop a small-scale model that can act as a seating structure using bamboo sticks and silicone elastic stripes for assembly. During the workshop, the teams had to negotiate their ideas, test them, and fabricate the model according to the proposed design. Beyond the hands-on experience of the workshop itself, participants had the opportunity to explore the Greenfeel site, allowing them to clarify various curiosities related to the overlapping of activities and the potential the space offers. Thus, the experience extended beyond project-based learning, incorporating elements of situational or circumstantial learning.

The space has successfully engaged a diverse demographic, welcoming participants of all ages and backgrounds, as documented in the accompanying images in

Figure 15.

4. Results

From a design and build process perspective, the bottom-up approach—by identifying the specific characteristics of users and target groups, as well as existing contextual factors and variables—represents a working method that can lead to a design brief responsive to real, context-adapted needs. Thus, the final project and physical architecture both reflect the ideas of contextuality through strong alignment with site-specific needs, characteristics, and social value through distinctive cultural values and adaptability through flexible, resilient design.

Through the reuse of construction materials and integration with existing on-site elements (such as a brick floor), the intervention demonstrates sensitivity to site-specific resources. The aspect of reversibility is also taken into consideration by means of concrete poured into detachable buckets, enabling easy extraction and dismantling of the entire wooden structure.

From the viewpoint of community engagement, temporary architecture—as exemplified by the case study The Garden of Impermanence—demonstrates that temporary structures have the potential to generate spaces that encourage interaction among diverse social groups. Such interventions can function as mediators between people and their natural surroundings, not only avoiding negative impact but also enhancing the value of the natural environment.

In terms of social sustainability, considered a core pillar of sustainable development, the case study highlights the project’s ability to create local memory and define a meeting place for idea exchange, knowledge-sharing, experimentation, and exploration. The series of events held at the pavilion so far reinforces the importance of equity, social cohesion, and community well-being as pathways to resilience and adaptability, contributing toward the creation of healthy, inclusive, and equitable societies.

From an educational perspective, exploration and experimentation are key dimensions addressed by the temporary architectural installations. These are seen as activities capable of generating innovative, out-of-the-box approaches. In the case study, the design workshop session focused on developing seating solutions using a single material in the smallest quantity possible, directly responding to the design challenge. On-site form-finding experiments played a significant role in shaping participants’ solutions, simply by providing a direct, hands-on encounter with an example grounded in the same principles and goals.

Guided by reflection-in-action and experiential learning, the pavilion itself acted as a pedagogical tool—demonstrating circularity, reversibility, and ecological integration in real time [

40,

41]. Recent research highlights the educational benefits of informal learning spaces—including outdoor and architectural environments—where learners spontaneously interact with materials, peers, and context [

43]. These environments support systems thinking, collaboration, and eco-justice, aligning with goals outlined in the OECD Learning Compass 2030 [

38]. In this framework, architectural space transcends its physical role to become an active agent in learning. The pavilion model enables reflection, dialogue, and embodied understanding. The pavilion’s non-formal educational uses attracted participants across ages and backgrounds, reinforcing social inclusivity and civic engagement. This illustrates how temporary architecture can serve as a vehicle for knowledge exchange, ethical design awareness, and environmental stewardship—key elements of social sustainability.

5. Discussion

This paper addresses the issue of temporary architectural interventions within an urban natural context and explores the intended and actual effects produced through urban acupuncture methods. The characteristics of temporality, impermanence, reversibility, and sustainability—at multiple levels, including the architectural object, construction materials, design and implementation processes, and local social impact—form the basis for debate in the decision-making process regarding design approaches and long-term use.

The study highlights the interdependence between the natural environment and human interventions, as well as the effects these generate, such as mutual enhancement, cohabitation between natural ecosystems and human-made structures, promoting ecological sensitivity, encouraging sustainable design practices, stimulating long-term environmental stewardship, and fostering inclusive, community-driven approaches to urban ecological regeneration.

5.1. Opportunities

According to the findings presented in the case study The Garden of Impermanence, several key aspects can be identified that influence approaches to temporary architectural interventions:

The extent to which participatory design is embedded in planning and decision-making.

The character of the intervention site—whether located in densely urbanized areas or in more open settings with a stronger natural landscape presence.

The thorough documentation and accurate identification of stakeholders involved in the use phase, including both current and potential future beneficiaries, in anticipation of evolving needs.

The opportunities emerging from this case study, which invite further discussion and exploration, include:

The potential of good practice examples—such as The Garden of Impermanence—to inspire new initiatives, acting as acupuncture-like activators within the urban fabric.

The role of public–private partnerships in identifying and activating underutilized urban areas.

The need for further studies on community actors and the strategies through which they can implement initiatives that enhance urban environments while maintaining harmony with local biodiversity.

5.2. Limitation of the Study

Like any situated, practice-based inquiry, this study has inherent limitations—some methodological, others contextual—that must be acknowledged. First, the project took place in a highly specific setting: an urban garden on the periphery of Timișoara, shaped by preexisting community engagement and a flexible land-use context. Consequently, the insights generated here may not fully apply to denser, more regulated urban environments or to spaces lacking an established social framework. Second, the intervention’s temporality—both in concept and physical presence—limited data collection to a relatively short observational period. While meaningful outcomes were observed, long-term effects—such as shifts in local behavior, community cohesion, or ecological dynamics—remain outside the scope of this initial study. The extensive assessment of this current study is an ongoing process, as the scope and timeframe focused on documenting immediate outcomes and also different benefits ranging from social to ecological ones. Third, the research relied primarily on qualitative and informal methods, including observation, interviews, visual documentation, and participatory engagement. These approaches suited the project’s exploratory and embedded nature but do not allow for quantitative generalization or statistically validated conclusions. Thus, the outcomes serve as hypotheses for future studies, which can include long-term metrics at different levels of analysis and the development of cross-disciplinary evaluation tools in order to determine the social and ecological impact. Additionally, though biodiversity and ecological sensitivity were key design priorities, the project did not incorporate formal environmental monitoring. Thus, while its ecological impact appears minimal and responsive, it remains qualitatively evaluated, not quantitatively verified. The project’s goal is to frame ecological awareness through a design attitude that can guide the design process, rather than perceiving it as merely a technological outcome.

Finally, discussions of memory, identity, and collective ownership are grounded in subjective interpretations, emerging from dialogue and lived experience. While these dimensions are rich and meaningful, they are also fluid and context dependent, resisting rigid categorization. Even though the project’s concept developed through a series of information documented from informal conversations or discussions that took place during community activities, which all underlined the need for a flexible space, the selection of environmentally friendly materials and techniques, the study does not incorporate real-time user feedback or structured evaluations. These limitations do not undermine the project’s value; instead, they underscore its exploratory nature.

5.3. Future Research Directions

The reflections gathered in this study point toward several meaningful directions for future inquiry. First, there is a clear need to test similar temporary and participatory interventions in diverse urban contexts—particularly in high-density or socially fragmented areas where access to green space is limited. The Garden of Impermanence project does not offer a solution that can be universally replicable in different urban sites but acts as a contribution to the catalogue of temporary architectures and highlights the potential of temporality and flexibility in urban design. Second, the long-term impact of such structures—on both communities and ecosystems—remains an open question. While the temporary nature of the pavilion was intentional, its enduring influence on behavior, memory, or biodiversity warrants future longitudinal studies. Third, future research could benefit from complementing qualitative methods with empirical tools, such as biodiversity monitoring or structured surveys on social impact. This would help connect subjective insights with measurable evidence. Finally, a more nuanced understanding of the non-human dimensions of such interventions—plants, insects, microclimates—could reposition temporary architecture as part of a broader ecological continuum, rather than a purely human-centered endeavor. Ultimately, these avenues converge toward a shared objective: to examine how ephemeral architectural gestures may generate enduring value across social, spatial, and ecological dimensions.

The case study reflects an example of an intervention initiated in a privately owned urban area, with the initiative supported by non-governmental entities through a private partnership. Thus, the value of the project lies in its ability to open up a private area to local communities and foster collaboration with actors outside the city’s local administration. This example of effective cross-sectorial and multidisciplinary collaboration can be replicated or integrated into the city’s strategies for areas under its ownership, which can be activated through acupunctural interventions in collaboration with the private sector.

Future studies may address comparative analyses of the types of interventions carried out by the private and public sectors, which could lead to the development of best practice guidelines applicable in more urbanized environments or in those with a more pronounced natural component. These guidelines could equally aim at generating beneficial effects on social cohesion—as interpreted through a set of keywords such as social relationships, sense of community, social identity, etc. [

44]—as well as on harmonizing the urban natural habitat with human presence in relation to it.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.G., V.G. and C.C.; methodology, D.G., V.G. and C.C.; software, D.G.; validation D.G., V.G. and C.C.; formal analysis, D.G.; investigation, D.G., V.G. and C.C.; resources, D.G. and V.G.; data curation, D.G., V.G. and C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, D.G., V.G. and C.C.; writing—review and editing, D.G. and V.G.; visualization, D.G.; supervision, V.G.; project administration, D.G. and V.G.; funding acquisition, D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The project from the study case was funded by Plai Cultural Center.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study by Institution Committee due to Romanian Law no. 78/2014 and EU Regulation 2016/679 (GDPR).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Plai Cultural Center for investing resources in the implementation process and for their valuable support and guidance throughout the development of the project. They also thank the Greenfeel Project for accepting the proposal within their property. Special thanks are extended to architect Amadeea Lazăr for making the implementation process possible, and to the Build&Chill team for their ongoing commitment to creative technical solutions throughout the construction phase. This research was supported by the Plai Cultural Center as part of the Future Divercities project. The authors also acknowledge the contributions of all participants and collaborators involved in site biodiversity and event documentation, without whom this work would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kaplan, R.; Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; ISBN 978-0-521-34139-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chiesura, A. The Role of Urban Parks for the Sustainable City. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabisch, N.; Qureshi, S.; Haase, D. Human–Environment Interactions in Urban Green Spaces—A Systematic Review of Contemporary Issues and Prospects for Future Research. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 50, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Bramley, G.; Power, S.; Brown, C. The Social Dimension of Sustainable Development: Defining Urban Social Sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 19, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Bosch, M. Urban Green Spaces and Health; World Health Organization European: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vallance, S.; Perkins, H.C.; Dixon, J.E. What Is Social Sustainability? A Clarification of Concepts. Geoforum 2011, 42, 342–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitrović, V.; Ignjatijević, S.; Vapa Tankosić, J.; Prodanović, R.; Lekić, N.; Pavlović, A.; Čavlin, M.; Gardašević, J.; Lekić, J. Sustainability of Urban Green Spaces: A Multidimensional Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashinze, U.K.; Edeigba, B.A.; Umoh, A.A.; Biu, P.W.; Daraojimba, A.I. Urban Green Infrastructure and Its Role in Sustainable Cities: A Comprehensive Review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2024, 21, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological Benefits of Greenspace Increase with Biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabisch, N.; Strohbach, M.; Haase, D.; Kronenberg, J. Urban Green Space Availability in European Cities. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 70, 586–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Byrne, J.; Newell, J.P. Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 125, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.; Till, J. Beyond Discourse: Notes on Spatial Agency. Footprint 2009, 3, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J. Urban Acupuncture; Muello, P.; Daher, A., Translators; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA; Covelo, CA, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Balicka, J.; Storie, J.T.; Kuhlmann, F.; Wilczyńska, A.; Bell, S. Tactical Urbanism, Urban Acupuncture and Small-Scale Projects. In Urban Blue Spaces; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 406–430. ISBN 978-0-429-05616-1. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, P.; Williams, L. The Temporary City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; ISBN 978-0-415-67055-5. [Google Scholar]

- Krmpotić Romić, I.; Bojanić Obad Šćitaroci, B. Temporary Urban Interventions in Public Space. Prostor 2022, 30, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pak, B. Enabling Bottom-up Practices in Urban and Architectural Design Studios. Knowl. Cult. 2017, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Musawi, M.H.; Ali, S.H. Temporary Architecture: A Strategy to Enhance the Light Competitive Image. In Networks, Markets & People; Calabrò, F., Madureira, L., Morabito, F.C., Piñeira Mantiñán, M.J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1187, pp. 245–257. ISBN 978-3-031-74703-8. [Google Scholar]

- Chabrowe, B. On the Significance of Temporary Architecture. Burlingt. Mag. 1974, 116, 385–391. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon, M.; Garcia, A. Tactical Urbanism; Island Press/Center for Resource Economics: Washington, DC, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-59726-451-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J.; MacKeith, P.B.; Tullberg, D.C.; Wynne-Ellis, M. Encounters: Architectural Essays; Rakennustieto Oy: Helsinki, Finland, 2005; ISBN 978-951-682-629-8. [Google Scholar]

- Norberg-Schulz, C. Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture; Rizzoli: New York, NY, USA, 1980; ISBN 978-0-8478-0287-6. [Google Scholar]

- Zumthor, P. Thinking Architecture; Birkhäuser: Boston, MA, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-3--3764361013. [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, A.; Assmann, A. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives; 1. English ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-0-521-16587-7. [Google Scholar]

- Huyssen, A. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. In Cultural Memory in the Present; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-0-8047-4560-4. [Google Scholar]

- Till, K.E. The New Berlin: Memory, Politics, Place; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-8166-4011-9. [Google Scholar]

- Ricœur, P.; Blamey, K.; Pellauer, D.; Ricœur, P. Memory, History, Forgetting; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-226-71342-7. [Google Scholar]

- Glade, P. Black Rock City, NV: The New Ephemeral Architecture of Burning Man 2011-2012-2013-2014-2015, 1st ed.; Real Paper Books: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-0-9837428-1-4. [Google Scholar]

- Haydn, F.; Temel, R. Temporary Urban Spaces: Concepts for the Use of City Spaces; Birkhauser Verlag AG: Zürich, Switzerland, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell-Jones, P.; Petrescu, D.; Till, J. (Eds.) Architecture and Participation; Digit. print.; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 978-0-415-31746-7. [Google Scholar]

- About Us—Greenfeel. Available online: www.greenfeel.ro (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Aerts, R.; Honnay, O.; Van Nieuwenhuyse, A. Biodiversity and Human Health: Mechanisms and Evidence of the Positive Health Effects of Diversity in Nature and Green Spaces. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 127, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benyus, J.M. Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature; Nachdr.; Perennial: New York, NY, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-06-053322-9. [Google Scholar]

- Concéntrico. A Table. 2022. Available online: https://Concentrico.Es/En/a-Table/ (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Betti, G. Salvaged Construction Waste Shapes Pavilion in Berlin, Calling for a Circular Design Process. Design Architectural Digest Magazine, 27 July 2023. Available online: https://www.Designboom.Com/Architecture/Salvaged-Construction-Waste-Material-Circle-Pavilion-Berlin-07-27-2023 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Ott, C. Afterlife of Pavilions: Exploring Reuse in Temporary Architecture. Available online: https://www.Archdaily.Com/996532/Afterlife-of-Pavilions-Exploring-Reuse-in-Temporary-Architecture (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Sparavigna, A.C.; Dastrr, L. The Pantheon, Eye of Rome, and Its Glimpse of the Sky. SSRN Electron. J. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Future of Education and Skills 2030/2040. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/about/projects/future-of-education-and-skills-2030.html (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- UNESCO. Guidelines for the Recognition, Validation and Accreditation of the Outcomes of Non-Formal and Informal Learning—UNESCO Digital Library. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000216360 (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; FT Press: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 0-13-389250-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, S.; Tilbury, D. Harnessing the Potential of Non-Formal Education for Sustainability. In EENEE Analytical Report; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton, S.E. Formal, Non-Formal and Informal Learning: The Case of Literacy and Language Learning in Canada; Ainsworth, H.L., Ed.; Eaton International Consulting, Incorporated: Calgary, AB, Canada, 2010; ISBN 978-0-9733594-3-5. [Google Scholar]

- Salih, S.A.; Alzamil, W.; Ajlan, A.; Azmi, A.; Ismail, S. Typology of Informal Learning Spaces (ILS) in Sustainable Academic Education: A Systematic Literature Review in Architecture and Urban Planning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Mazumdar, S.; Vasconcelos, A.C. Understanding the Relationship between Urban Public Space and Social Cohesion: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Community Well-Being 2024, 7, 155–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Event based temporary structures at Banat Village Museum. (a) Plai festival, 2015 edition; (b) Plai Festival, 2016 edition, credits Plai Festival; (c) Plai Festival, 2017 edition.

Figure 1.

Event based temporary structures at Banat Village Museum. (a) Plai festival, 2015 edition; (b) Plai Festival, 2016 edition, credits Plai Festival; (c) Plai Festival, 2017 edition.

Figure 2.

Event-based temporary structures at Banat Village Museum (a) Plai festival, 2021 edition; (b) Plai Festival, 2021 edition; (c) Plai Festival, 2022 edition.

Figure 2.

Event-based temporary structures at Banat Village Museum (a) Plai festival, 2021 edition; (b) Plai Festival, 2021 edition; (c) Plai Festival, 2022 edition.

Figure 3.

Location of Greenfeel. (a) Greenfeel urban garden within the city of Timișoara; (b) Greenfeel limits. Diagram by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 3.

Location of Greenfeel. (a) Greenfeel urban garden within the city of Timișoara; (b) Greenfeel limits. Diagram by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 4.

Greenfeel (a) Green feel property limits; (b) land use–functional zoning: residential, urban gardening plots, socializing, sport activities, beekeeping. Diagram by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 4.

Greenfeel (a) Green feel property limits; (b) land use–functional zoning: residential, urban gardening plots, socializing, sport activities, beekeeping. Diagram by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 5.

Collection of examples of biodiversity flora and fauna at Greenfeel. Photo-documentation by Petru Cojocaru.

Figure 5.

Collection of examples of biodiversity flora and fauna at Greenfeel. Photo-documentation by Petru Cojocaru.

Figure 6.

Form finding conceptual hand-drawings: Site analysis for the identification of the optimal insertion place according to the existing functions, conceptual drawings—the opportunities of a circular layout which can facilitate the connection with the surrounding areas and the exploration of effects of centered core versus a shifted inner core, cross section effects, perspectives.

Figure 6.

Form finding conceptual hand-drawings: Site analysis for the identification of the optimal insertion place according to the existing functions, conceptual drawings—the opportunities of a circular layout which can facilitate the connection with the surrounding areas and the exploration of effects of centered core versus a shifted inner core, cross section effects, perspectives.

Figure 7.

Technical drawings and rendering on photo insertion.

Figure 7.

Technical drawings and rendering on photo insertion.

Figure 8.

Foundations made with bucket poured concrete. (a) Close-up photo; (b) construction site. Images by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 8.

Foundations made with bucket poured concrete. (a) Close-up photo; (b) construction site. Images by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 9.

Brick work—recovered brick used for the extension of the existing floor. (a) Preparation of the support for brick layering; (b) brick floor patterning. Images by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 9.

Brick work—recovered brick used for the extension of the existing floor. (a) Preparation of the support for brick layering; (b) brick floor patterning. Images by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 10.

Material reuse—wooden plank recovered from the 2021 Plai Festival installation and reused in the Garden of Impermanence pavilion. (a) Temporary architecture at Plai Festival 2022; (b) Greenfeel site with recovered wooden planks from the wooden temporary installation at Plai Festival, 2022 edition. Image by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 10.

Material reuse—wooden plank recovered from the 2021 Plai Festival installation and reused in the Garden of Impermanence pavilion. (a) Temporary architecture at Plai Festival 2022; (b) Greenfeel site with recovered wooden planks from the wooden temporary installation at Plai Festival, 2022 edition. Image by arch. Amadeea Lazăr.

Figure 11.

Side-by-side images of the completed project taken one year apart. (a) May 2024, (b) May 2025. Noticeable signs of material aging towards a natural camouflage within the green landscape.

Figure 11.

Side-by-side images of the completed project taken one year apart. (a) May 2024, (b) May 2025. Noticeable signs of material aging towards a natural camouflage within the green landscape.

Figure 12.

Signs of natural assimilation (a) Grown vegetation at the base of the columns, (b) intensive vegetation in the inner core, (c) ensemble image with vegetation presence, natural lights and shadow.

Figure 12.

Signs of natural assimilation (a) Grown vegetation at the base of the columns, (b) intensive vegetation in the inner core, (c) ensemble image with vegetation presence, natural lights and shadow.

Figure 13.

The oculus in the roof of the pavilion marking the connection with the sky.

Figure 13.

The oculus in the roof of the pavilion marking the connection with the sky.

Figure 14.

Workshop on beekeeping conducted by Lucian Avramescu. Photos by Sebastian Tataru.

Figure 14.

Workshop on beekeeping conducted by Lucian Avramescu. Photos by Sebastian Tataru.

Figure 15.

Design workshop at the Garden of Impermanence workshop. (a) The pavilion offering sun shade for the worjshop participants; (b) Design assignment presentation; (c) Hands-on activity–form finding through trial-and-error experience; (d) model testing.

Figure 15.

Design workshop at the Garden of Impermanence workshop. (a) The pavilion offering sun shade for the worjshop participants; (b) Design assignment presentation; (c) Hands-on activity–form finding through trial-and-error experience; (d) model testing.

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).