Abstract

Sustainability research in Living Labs promises innovation through real-world experimentation. These settings require the integration of key design principles—such as participation, co-creation, and real-life application—into everyday research. Yet collaboration among diverse actors is often accompanied by persistent tensions and conflicts. This study examines a Living Lab project embedded in the net-zero transformation of a corporate city. It focuses on identifying and explaining key challenges in the daily collaboration between academic and non-academic actors, as well as the strategies used to cope with them. Following a qualitative approach, data were generated through twenty in-depth interviews and participant observations. We identify uncertainties, frustrations, overload, tensions, conflicts, and disengagement as recurring reactions in transdisciplinary collaboration. These are traced back to the following five underlying proto-challenges: (1) divergent interpretations of Living Lab concepts, (2) conflicting views on sustainability interventions, (3) difficulties in role positioning, (4) processes of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and (5) the embedded complexities of Living Lab governance. By linking these findings to Institutional Theory and Paradox Theory, we argue that the proto-challenges are not merely contingent barriers but constitutive tensions—implicitly inscribed into the normative design of Living Lab research and essential to engage with for advancing collaborative sustainability efforts.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development is often referred to as a ‘wicked problem’ [1,2,3]. By definition, wicked problems resist resolution, owing to their complexity, dynamic environments, and incomplete or changing requirements [1,4]. In the pursuit of sustainability goals, non-standard, innovative, and transdisciplinary research approaches have shown promise. Research into Living Labs is gaining scientific as well as political attention in particular [5,6,7,8,9]. Living Labs play a central role in delivering the European Commission’s Zero Pollution Action Plan in the years ahead [10]. The European Commission strategically supports Living Labs to strengthen sustainability innovation in the European Union. Furthermore, the European Network of Living Labs [10] was established in order to connect European Living Labs to facilitate knowledge exchange [11].

Although a variety of definitions for Living Labs can be found in the literature [11,12,13,14], several core characteristics are commonly recognised as defining features. Living Labs are usually created in real-life environments, focusing on everyday practice and research. They integrate a broad range of stakeholders, such as cities, local communities, enterprises, public administration, political actors, and the scientific community [15,16,17,18]. Living Labs entail a striving for openness and newness [7,19], such as developing and establishing new practices and artefacts. Arguably the most defining feature of Living Labs lies in their mode of knowledge and practice generation; nominally that they enable the transdisciplinary co-creation of sustainability interventions through iterative learning and development processes [16]. A key normative dimension of Living Labs lies in the collaborative production of results, aimed at empowering all participating actors and stakeholders [20]. Living Labs create spaces for collaborative experimentation and render sustainability experiments a core meta-method [21].

The implementation of Living Labs frequently constitutes both a novel experience and a practical challenge for academic and non-academic actors engaged in day-to-day research activities. In recent years, an increasing number of studies have focused on challenges in transdisciplinary research, often equated with barriers [22,23], tensions, dilemmas, or paradoxes [24,25]. Hossain et al., 2015 [16] (p. 983), stress the challenges related to the methods and concepts of Living Labs explored in past studies. Despite the fact that these challenges are diverse and dependent upon the specific contexts in which a Living Lab is situated, they identify several universal challenges. These include governance, unforeseen outcomes, efficiency, the recruitment of collaborators, and the sustainability and scalability of their innovations. Tensions and conflicts play a notable role in the analytical examination of challenges in Living Labs [9,26]. Hakkarainen and Hyysalo [27] point to the general potential for conflict resulting from the heterogenous competencies or contradictory interests of participating actors. In the same vein, Engels and Rogge [28] address tensions arising from the unilateral compulsion to achieve rapid innovation and eco-nomic exploitation within Living Labs. Furthermore, they set out the challenge of integrating new participants into the Living Lab. On occasion, this can undermine existing actor dynamics and threaten the established order, thus manifesting a negative consequence of the openness principle.

The academic discourse on challenges in transdisciplinary research highlights, first, a practical need for structural orientation within the research process—particularly in the field of sustainability science. This is reflected in studies proposing quality or evaluation criteria [29,30], implementation procedures [21,24], practical frameworks for transdisciplinary collaboration (Plummer [31]), and coping strategies for tensions and conflicts in collaborative settings [32]. Second, this discourse underscores the need for a better understanding of the factors that challenge collaboration and how to address them in day-to-day research practice [17,28], as well as for further research into co-creation processes in Living Labs [6,7,33,34,35].

Responding to these demands, our study aims to accomplish the following: (1) identify and describe the main challenges of collaboration in Living Labs and (2) highlight coping strategies for academic and non-academic actors. The findings are drawn upon the experience of three years of transdisciplinary activities in one Living Lab research project. Targeting the transition to climate neutrality within the scope of a corporate city (Konzern Stadt) in southern Germany, the Living Lab integrates domains such as urban mobility, day-to-day practices, energy and heating supply, energy communities, buildings, and infrastructure as areas of transdisciplinary experimentation. This empirical case is characterised by a vast diversity of collaborators and stakeholders, as well as complex governance structures.

Our research questions are as follows:

- (i)

- What are the key challenges academic and non-academic actors have to consider in day-to-day Living Lab research?

- (ii)

- What constitutes and shapes the key challenges in collaboration?

- (iii)

- What coping strategies can be applied?

We attempt two contributions to the body of knowledge on Living Lab research by (1) exploring and describing the key challenges to consider in creating and maintaining successful collaboration in Living Labs and (2) synthesising these findings to propose various coping modes.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines the key principles of Living Lab research that provide the conceptual framework for collaboration. Section 3 details the methodology, data sources, and analytical procedures employed. Section 4 presents the main challenges identified and situates them in relation to the existing literature. Section 5 discusses the findings through the lens of three distinct coping modes. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper by summarising key insights, acknowledging limitations, and outlining directions for future research.

2. Key Principles of Research in Living Labs

Research in Living Labs is conceptually different from traditional research in both the natural sciences and the social sciences [24,29,36]; a set of specific normative principles has to be applied. In the following, we elaborate on those key principles owing to the fact that, first, they set the framework within which a Living Lab should be created, organised, and governed; second, the collaborators (academic as well as non-academic actors) are required to commit themselves to those principles in everyday research; and third, those principles are interpreted, discussed, and translated in relation to day-to-day practice.

2.1. Transdisciplinarity, Participation, and Co-Creation in Living Labs

Transdisciplinarity represents the overarching characteristic feature of Living Labs research [11,15,16,21,35,37,38]. According to Barth [37], transdisciplinarity in Living Lab research acknowledges context dependencies related to real-world problems and ‘differentiates and integrates knowledge from different domains, inside and outside academia’ [37] (p. 2). The idea of co-creation is inherent in the concept of transdisciplinary Living Lab research [11,15,16,39,40,41]. Targeted and co-created solutions promise less implementation effects when interventions are introduced in the collaborators’ own context, and evaluative claims are likely to be well-grounded [11,42,43,44].

2.2. Variety of Collaborators and Real-Life Setting

Living Labs bring together collaborators to co-create sustainability solutions, products, and innovations in the physical setting in which they are envisioned and ought to be implemented [11] (p. 1211). The inclusion of multiple collaborators in the research process is constitutive for Living Labs. Collaborators can thus be actors from universities or other research institutions, private or state-owned companies, governmental or non-governmental organisations, urban or rural citizens, and agencies, among others [11,12,15,38,45]. However, with regard to studies on challenges, the range of collaborators is most frequently narrowed down to the distinction between scientific and non-scientific actors [37] (p. 2), [46], highlighting the threshold with respect to real-life settings.

2.3. Experimentation as a Meta-Method of Sustainability Interventions

In many sciences, experiments are the key method used to gain knowledge and to explore, validate, or refute hypotheses. Epistemologically, the experiment constitutes an inductive approach to drawing general conclusions from individual cases. Classical experiments in laboratories can be characterised by the need to control contextual conditions. Similar, but different, experiments constitute the meta-method of creating knowledge in Living Labs. In contrast to classical experiments, Living Lab experiments (other commonly used terms are ‘real-life experiments’, ‘transition experiments’, ‘transformational experiments’, or ‘sustainability experiments’) are embedded in social, ecological, and technical processes, and conducted and supported by multiple contributors [31,47,48,49], thus limiting the overall controllability and increasing the potential for unintended consequences [11,31,50].

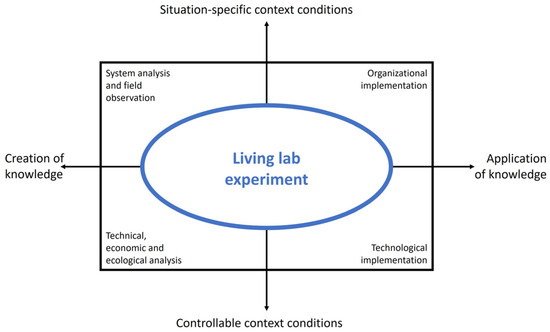

Taking a sociological perspective, Groß et al. [20] typify the characteristics of Living Lab experiments in the following two ways: first is the combined application and generation of knowledge and second is the distinction between situational and controllable context conditions within the field of experiments in sciences. First, the collaborators and stakeholders in the Living Lab constitute the experimenters who are themselves part of the experiments, as well as part of the intervention [51]. Second, Living Lab collaborators, embedded in real-world settings, face context-specific challenges, including exogenous events and organisational particularities. Second, due to their embeddedness in the real-world environment, Living Lab collaborators have to deal with situation-specific context conditions, such as specific exogenous events or influences, or case-specific organisational histories, structures, and cultures. Identifying these situation-specific context conditions becomes vital to being able to draw general conclusions for other contexts. Furthermore, and in contrast to classic experiments, experiments in Living Labs can take spontaneous turns and yield unexpected results [11,50].

2.4. Multiple Methods Approach—Spaces of Collaboration

The application of multiple methods is a basic requirement of experiments in Living Labs [6,11]. Reviewing forty-two empirical articles on Living Labs, Huang and Thomas [40] provide a comprehensive overview, as well as a thematical categorisation of the vast variety of methods used in Living Labs. They outline eight thematic domains of user engagement in Living Labs, each associated with specific methodological approaches, ranging from structured formats like surveys and usability testing to more flexible, creative tools, such as co-creation workshops, storytelling, and hackathons. Together, these domains emphasise the importance of inclusive processes, diverse actor involvement, and adaptive design principles for facilitating participation across different phases of innovation. These methods focus heavily on the involvement of academic and non-academic collaborators and represent the primary ‘spaces of participation’ [9]. At the same time, the challenges of collaboration manifest themselves in these interactive settings.

3. Materials and Methods

From a paradigmatic and epistemological standpoint, this study is grounded in a social constructivist worldview [52]. This perspective is rooted in the sociological premise that meanings—such as those attributed to collaboration within a Living Lab—are co-constructed through social and cognitive interpretation processes. Practices and interventions are thus understood as emerging from, and shaped by, these socially negotiated meanings [53]. Grounded in an interpretive paradigm [54], our research strategy aimed to (re)construct both the emergence of collaborative challenges and the ways in which actors responded to them, by identifying underlying themes and patterns.

Data generation and analysis follow an explorative qualitative approach and a single case study design [55]. This study draws on empirical data from a single Living Lab project, conducted within a corporate city context, targeting the transition toward climate neutrality. The subsequent section provides an overview of the Living Lab’s structure, objectives, and partnership constellation, followed by an explanation of the research process with regard to data generation and analysis.

3.1. Living Lab and Single-Case Description

The Living Lab is situated in a city in the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg (c. 120,000 inhabitants); it has set itself the ambitious goal of achieving climate neutrality by 2040. Undoubtedly the transition to climate neutrality is a complex mission in urban contexts, particularly considering the institutional governance frameworks in European cities [56]. In German cities, climate protection at the municipal level is typically organised, managed, and addressed within the governance model of the “corporate city”. The concept of the ‘corporate city’ (ger. Konzern Stadt) refers to a model of municipal governance in which the city is structured and managed analogously to a corporate enterprise [57,58,59]. This approach emphasises strategic steering, performance-based management, and the separation of political leadership from operational execution. Often associated with the New Public Management reforms of the 1990s, the corporate city model treats administrative units, municipal enterprises, and public–private partnerships as subsidiaries within a larger organisational framework, aiming to enhance efficiency, accountability, and service orientation [60].

Against this background, our Living Lab research project aimed at exploring and supporting the transition to climate neutrality in the context of a corporate city (cf. Table 1). The Living Lab project was initiated by Reutlingen University as part of a federal funding programme for sustainability-oriented Living Lab initiatives (see acknowledgments), and was jointly conceptualised over a six-month period in collaboration with partners from the corporate city and academia. This initial phase of the project included a series of workshops aimed at defining the thematic areas of research focus, as well as the governance structure and roles.

Table 1.

Living Lab characteritsics overview.

As corporate cities have to tackle a broad spectrum of climate protection-critical tasks of general interest, energy production and communities (1), climate-neutral heat generation (2), buildings and infrastructure (3), mobility (4), behaviour, and action in everyday organisational life (5) were defined as areas of experimentation. The Living Lab experiments were carried out in these areas from 2021 to 2024. Hence, our data collection and analysis derive from a three-year period.

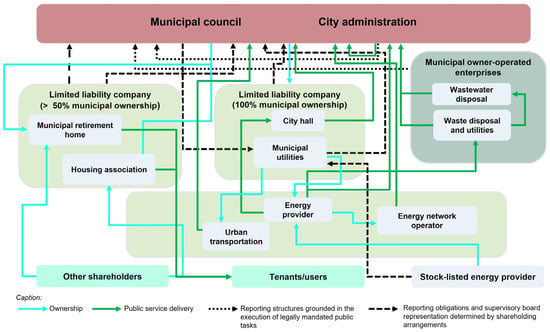

Both our empirical case study and the Living Lab are characterised by a high degree of actor diversity and intricate governance structures. At the level of the real-world setting, the corporate city comprises the municipal administration, the city-owned and -operated enterprises, and municipal businesses in which the city holds a significant stake. The governance structure of the case study (Figure 1) provides insight into the context in which municipal climate protection ought to be organised. Collaborators from these organisational units represent what are commonly referred to as the non-academic actors—or practitioners—involved in the Living Lab project.

Figure 1.

Governance structure of the studied corporate city.

At the academic level, the Living Lab involves personnel from various scientific disciplines (e.g., social sciences, economics, and engineering) affiliated with two research institutes, as well as an additional partner supporting moderation processes and an external partner providing coaching and supervision.

3.2. Governance and Experimentation Within the Living Lab

The key design principles of Living Lab research imply not only the establishment of adequate governance structures for project implementation, but also a nuanced understanding of the perspectives of diverse collaborators in order to facilitate the integration of heterogeneous stakeholders [61,62] and roles [63,64]. Accordingly, the workshops held during the initial phase of the project served as stakeholder analysis sessions aimed at identifying expectations, collaboration conditions, and possible roles in the project.

As a key premise of the Living Lab governance, a parity-based operational management structure—comprising both academic and non-academic actors—was established for the overall project, as well as for the five experimentation domains. To support the evaluation of the research process, a so-called steering team was set up. This team consists of 25 representatives from various hierarchical levels within the corporate city and meets regularly (every eight weeks) to contribute to joint problem and solution definitions, the assessment of interim results, and strategic decisions within the research process.

Reflection on the research process was an integral component of the Living Lab governance by engaging external academic advisors to provide supervision and facilitate workshops. This supervision included group discussions, workshops, and individual coaching sessions throughout the project duration.

In transdisciplinary sustainability research, the need for reflection particularly concerns the epistemological implications of experimentation. As noted above, Living Lab experiments serve a dual function and are subject to limitations in controlling contextual conditions. Figure 2, drawing on Groß [20], visualises the conceptual framework guiding the Living Lab experiments in the examined case.

Figure 2.

Classification of experimentation in Living Lab case study (adapted from Groß et al., 2005 [20]).

In order to better understand the situational context of the Living Lab, the supervision process was originally conceived to be complemented by a social science inquiry. The emergence of tensions, conflicts, and frustrations—particularly during the first year of the project—ultimately led to the development of our study and the focus on challenges in collaboration.

3.3. Research Process: Data Generation and Analysis

Following an interpretive qualitative approach, the research process was designed as cyclical and reflexive, enabling a dynamic interplay between empirical material and conceptual development [54]. The data generation was mainly based on qualitative interviews with collaborators (academic and non-academic actors) engaged in the Living Lab. Everyday involvement was the key criterion in the sampling process. The sampling strategy targeted collaborators heavily involved in both the coordination and implementation of the experiment.

Interviews were conducted with academic actors and city practitioners who are particularly involved in the day-to-day collaborative work across the five experiments. In total, twenty in-depth interviews (one-on-one and in a group) were carried out, with an average duration of around two hours each (cf. Table 2).

Table 2.

Shares on the roles of the interviewed persons of the Living Lab.

The interview data were generated by means of semi-structured, problem-centred interviews—a narrative interview format guided by a thematic guide [54,65]. This open-ended interview approach aims to provide participants with the opportunity to express themselves freely, while maintaining a focus on a defined problem—in this case, challenges of collaboration within the Living Lab—to which the interviewer repeatedly redirects the conversation as needed.

The interviews were guided by the following narrative-generating questions:

- 1.

- How would you describe your tasks and your own role within the Living Lab?

- 2.

- How have you experienced the collaboration within the Living Lab so far?

- 3.

- What indicators do you perceive that suggest the collaboration in the Living Lab is going well, or becoming difficult or challenging?

- 4.

- How do you act within the Living Lab when collaboration becomes difficult or challenging?

The guiding questions were used in an adaptive manner, aligned with the dynamics of each conversation. Situational follow-up prompts were used to explore contextual occurrences and conditions, underlying reasons, explanations, contrasts, and personal opinions. The interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed, and manually analysed; no software was used.

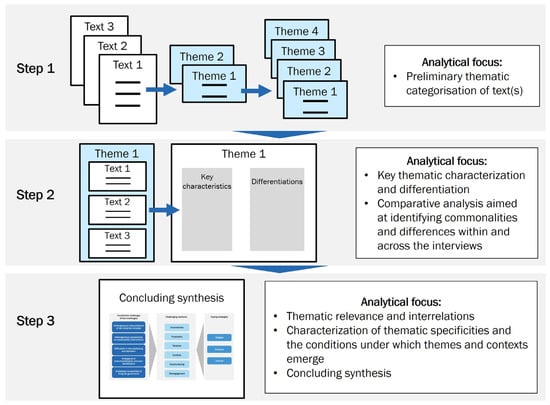

In addition to the interviews, observations drawn from participation in workshops, project meetings, and formal and informal discussions were included in the process of data generation. The generated texts (primarily interview text and observation protocols) were analysed by means of thematic analysis [54]. Thematic analysis provides an overview of interview content by summarising core themes and examining their contextual relevance. The diverse themes addressed are systematised and condensed through several analytical steps (cf. Figure 3), which are as follows: identifying themes and their characteristics, and assessing their relation to the central object of inquiry—in our case, the system Living Lab and challenges of collaboration [66]. Thematic analysis does not merely involve the formal identification and description of themes—as is more typical of content-analytical approaches—but rather constitutes an interpretive process that focuses on the interrelations and systemic dynamics of the themes themselves [54].

Figure 3.

Analytical procedure: thematic analysis (adapted from Froschauer and Lueger) [54].

3.4. Research Integrity: Quality Assurance and Ethical Considerations

Anchored in an interpretive epistemology, our study follows Froschauer and Lueger’s [54] (p. 201) contention that qualitative research cannot be evaluated through the lens of quantitatively derived quality criteria. Accordingly, we adopted their reflexive quality assurance principles to ensure coherence and rigour throughout the research process. These included the cyclical organisation of the research process, collaborative interpretation of textual data within the research team, and the integration of external perspectives through supervisory support. As part of this supervision, both regular coaching workshops and ad hoc workshops were conducted. For instance, preliminary findings from the interview study were discussed in a workshop held in November 2023, during which potential courses of action were jointly developed.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the German Sociological Association and the Professional Association of German Sociologists [67]. Core ethical principles—namely avoiding harm, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality, and obtaining informed consent—guided all stages of the research process. Given the study’s focus on collaborative challenges in transdisciplinary research, including potentially stressful or sensitive situations, particular attention was paid to protecting participants from harm and safeguarding their identities. These principles also shaped the presentation of our findings in the following ways: we deliberately abstracted descriptions of challenging interactions and refrained from using extended narrative illustrations that might allow for identification. Direct quotations from interviews or observations were omitted; only in rare cases were individual terms (e.g., ‘muddling through’) cited, to preserve contextual nuance. As a limitation, it must be acknowledged that the results may still reflect identifiable distinctions between participant groups (e.g., academic vs. non-academic actors, junior researchers vs. project leaders).

4. Results

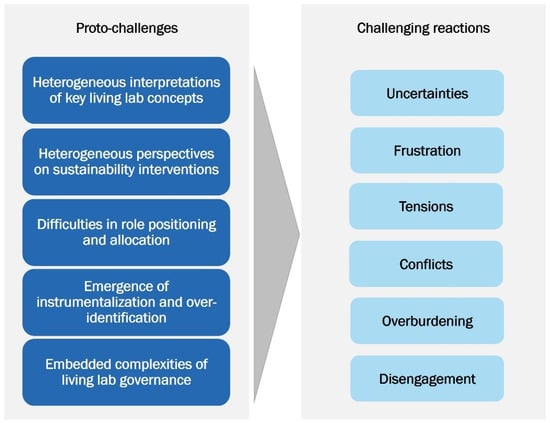

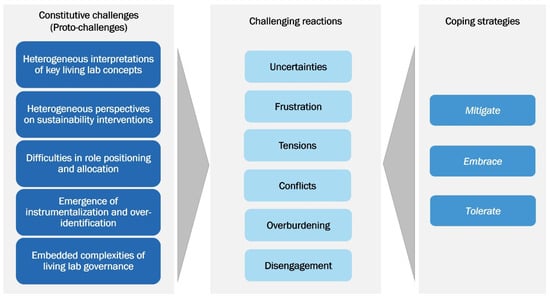

As outlined in the introduction, numerous studies [16,22,23] point to challenges in collaborative research, yet a clear and consistent conceptualisation of the term remains largely absent. For example, conflicts [9,26,27] undoubtedly pose challenges to collaboration in everyday research. However, our data analysis suggests that such situations are better understood as contingent outcomes of distinct underlying processes—what we refer to as proto-challenges. Consequently, interview responses that reflected negatively perceived aspects of collaboration—whether articulated explicitly or implicitly—were categorised as challenging reactions. These included expressions of uncertainty, frustration, overburdening, tension, conflict, and disengagement.

Such challenging reactions often represent turning points in the collaborative process, potentially disrupting or impeding the progress of a Living Lab research project. Our analysis shows that these reactions are shaped by (1) heterogeneous interpretations of key Living Lab concepts, (2) heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, (3) difficulties in role positioning and allocation, (4) emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and (5) embedded complexities of Living Lab governance (Figure 4). The following sections describe and discusses these interrelated proto-challenges within the broader context of existing research.

Figure 4.

Overview—challenging reactions and proto-challenges of Living Lab collaboration.

4.1. Heterogeneous Interpretations of Living Lab Key Concepts

Designing and establishing a Living Lab project requires the translation of the key concepts into practice. For this reason, the key concepts were introduced and discussed in a series of workshops during the initial design phase of the project in order to achieve a joint understanding among all collaborating actors. Since then, Living Lab experimentation, participation, and co-creation have established themselves as shared pillars of collaboration, as well as points of reference in day-to-day research. While the analysis of interviews and observation protocols indicated broad agreement on the importance of the key principles, it also revealed a lack of uniform interpretation among the collaborators. On the contrary, we identified distinct differences in the interpretations of these concepts, mostly embedded in narratives and reports about challenges, such as uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts, and disengagement.

From an organisational sociology perspective, individual actors’ interpretations are shaped by institutional logics and organisational cultures, which are embedded in the broader contextual settings of the collaborators, as well as in their personal experiences and interests [68]. Institutional logics, as well as organisational cultures, are defined as the socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, taken for granted assumptions, values, and beliefs by which individuals and organisations provide meaning to their day-to-day activities.

Transdisciplinary research practice routinely confronts collaborators with diverse and sometimes contradictory institutional logics that shape expectations, roles, and decision-making [69,70,71,72]. In their study on scientists’ narratives of participatory research, Felt et al. [73] demonstrate how institutional logics rooted in the scientific profession influence how roles are interpreted and assigned, as well as the extent of researchers’ engagement in participatory practices. In their study of four European Living Labs, Huning et al. [36] similarly highlight the important role and logic of their institutions, to which team members are typically attached.

In addition, prevailing power structures, power dependencies, bureaucratic structures, informal networks, or capacities for actions within participating organisations might prove challenging in Living Lab research [71,74]. Furthermore, and countering a top-down perspective on institutional logics, the individual interests, values, attitudes, experiences, and qualifications of participants enable or constrain collaboration within Living Labs [70,75].

4.1.1. Heterogeneous Interpretations of Living Lab Experimentation

The analysis revealed a range of divergent perceptions regarding both the Living Lab concept as a whole and the notion of experimentation. In the interviews, these ideas were often articulated as retrospective reflections—emerging in the context of narrating or evaluating challenges encountered in everyday research practice. Participants typically referred either to the demanding nature of their roles within the project or to their individual attitudes, experiences, and interests.

Across the spectrum of collaborating actors, the Living Lab format is predominantly perceived as a means of activism to accelerate sustainability transformation. Non-academic—and particularly academic—actors frequently emphasised their motivation to make a difference in the real world and their willingness to engage in the project as an agent of sustainability. In contrast, academic actors at times regard the Living Lab concept as little more than a fashionable label for practices already common in applied science. This viewpoint was especially articulated by interviewees with an engineering background, who pointed to the routine integration of sustainable technologies into practical applications. Less frequently, academic actors adopted a more distanced view, which at the same time marked a rejection of the notion of activism and was more oriented towards the classical research perspective. Therefore, merely observing the transformation and engaging as little as possible is seen as the appropriate approach to research practice. In addition to this orthodox view, critically pessimistic interpretations were also articulated in individual cases. For a few academic actors, the Living Lab approach represents an overhyped and time-consuming research trend with little impact on sustainability. This view is sometimes also shared by non-academic actors and justified by unfulfilled expectations.

Not fulfilling methodological and epistemological expectations is a central concern of the academic actors in day-to-day research life, manifesting in uncertainties and tensions. Experimentation is therefore described as a continuous process of ‘muddling through’, accompanied by the constant uncertainty of not having guaranteed an appropriate, valid, and proper research process—a process characterised by the struggle between freedom and boundaries inherent in questions such as the following: How should, may, or must the test room be designed and controlled? How should the interventions be tested? How should the diverse context be taken into account in the design, evaluation, and conclusions of the experiments? How should the established organisational or group rules of the real-life setting be dealt with? These questions remain fairly open, even upon completion of the experiments, as do the uncertainties. Feelings of guilt, doubts, and self-criticism were often described as familiar sentiments associated with Living Lab research.

The expectation to generate successful solutions places considerable pressure on both academic and non-academic actors. Despite the often-ambiguous formulation of project goals, the Living Lab framework conveys an implicit promise of concrete progress and innovation. In response, collaborators tend to showcase presentable outcomes, frequently downplaying or concealing the setbacks and failures encountered during experimentation. A number of studies have already pointed to this push towards ‘solutionism’ [36,76]. Maasen and Lieven explore the ‘pressure management’ that is required in transdisciplinary projects in order to cope with the pressure to produce ‘at least preliminary and always presentable results at all stages of the project’ [77] (p. 403). Similarly, Engels and Rogge address tensions arising from the unilateral urge to achieve rapid innovation and economic exploitation within Living Labs [28].

4.1.2. Heterogeneous Interpretations and Aspirations of Participation and Co-Creation

Felt et al. conclude in their study on transdisciplinary sustainability research that ‘Scientists do not talk about participation as a single coherent phenomenon,’ [73] (p. 15). Similarly, our analysis reveals distinct differences in the individual and collective ideas of participation. It is worth noting that the participants’ own interpretations often contrasted with the ideas expressed by other collaborators or with their former aspirations. Reflecting deeper tensions and conflicts, such juxtapositions frequently give rise to polarised dynamics characterised by starkly opposed viewpoints.

Framed as an ‘obligation of acceptance,’ this extreme position constrains participation to passive compliance, with decisions defined solely by project or organisational leadership. Put in less drastic terms, this view perceives participation as a means to achieve acceptance from everybody involved. In contrast to this is the opposing extreme position of ‘egalitarian-ism and heterarchy’, which is an idealistic view held by participants who are eager to co-create. It emphasises a voluntary, non-hierarchical formation of equal partners in any given situation. These extreme positions were problematised mainly by the academic actors. While academic actors frequently locate themselves and others along a continuum between two extremes, non-academic actors typically exhibit a more passive or less self-reflective orientation. This is primarily due to the academics’ assumption of exclusive responsibility for ensuring participatory and co-creative principles throughout the research process. From the perspective of the academic actors, the research process is marked by persistent uncertainty. Every form of collaboration is shaped by the following omnipresent question: What kind of participation is ‘right’, ‘appropriate’, or ‘enough’? Similarly, Felt et al. have pointed to the struggle of early-stage researchers ‘to clarify whether or not, or to what degree they are transdisciplinary’ [46] (p. 518).

Uncertainties emerge even in seemingly straightforward situations, such as organising a workshop or project meeting. Researchers ask themselves questions such as the following: Should I simply draw up a first proposal myself that can then be discussed, or should I first suggest a joint meeting? Although such uncertainties are usually pushed aside in everyday research in favour of a pragmatic approach (in this case writing a first draft), there remains a constant doubt and a guilty conscience about not fully adhering to the principles of participatory research.

Tensions or conflicts surrounding participation are, by contrast, more difficult for collaborators to navigate. They tend to emerge in more fundamental situations—particularly when essential research decisions are at stake. In our research case study, the definition of participation that was to form the basis for decisions made within the Living Lab was not comprehensively clarified at the beginning of or in the course of the research process. As there is no certainty as to what constitutes sufficient participation, and as there are no quality criteria in the scientific literature, the participants could rely only on their subjective and situational interpretations. Furthermore, tensions and conflicts tend to be attributed to individual actors who are seen as the cause of these issues. Actors who take a rather heterarchical view tend to find decisions that are not clearly based on consensus problematic. Decisions that are made on the basis of scientific expertise, majority consensus, or from a position of power would not be in line with the fundamental principle of participation. The use of veto power derived from hierarchical authority (e.g., by project or organisational leaders) is widely regarded as a critical point of contention. This results in frustrations, tensions, or even conflicts over ‘non-participatory’ procedures.

In particular, project and organisational leaders often describe themselves as being forced into an overburdening role in resolving the perceived contradiction between participation and co-creation on the one hand and effectiveness and efficiency on the other. The expressed contradiction between ‘efficiency’ and ‘participation’ can, in line with Paradox Theory, be understood as a paradoxical tension that resists straightforward resolution [78,79,80]. As those formally and primarily responsible for delivering the project objectives, project leaders feel compelled to adopt a pragmatic stance toward participation and co-creation. Furthermore, they find themselves confronted with the following inherent paradox: on the one hand, the ambiguity of the interpretations of those somewhat abstract ideals results in the aforementioned uncertainties, tensions, frustrations, and conflicts in collaboration; on the other hand, this ambiguity allows them to bypass these issues.

Interpretations of—and particularly aspirations regarding—participation evolve over time. Non-academic actors occasionally felt overwhelmed by the intensity of collaboration requests from academic counterparts, leading to phases of disengagement. This, in turn, generated frustration among academic actors, who approached participation from a more heterarchical perspective. Similarly, Felt et al. describe ‘the researchers’ astonishment and disconcertment when extra-scientific partners insist on a work-sharing model instead an integration model’. In addition, some non-academic actors positioned themselves as mere data providers, as they saw no other useful way of participating than by contributing data [73] (p. 14).

Overall, work-sharing in separated spaces constitutes the main model of collaboration in day-to-day research in our case study. Considering the time constraints, the high demands of daily communication and coordination, and the pressure to deliver results, this model has emerged as a viable practice in mitigating challenging reactions. Particularly for the academic actors, this mode provides practical benefits. First, it mitigates the risk of the research being too dictated by the demands of the non-academic actors. Second, it encourages disengagement on the part of actors and guards against the views of those who share a rather hierarchical view on participation.

4.2. Heterogeneous Perspectives on Sustainability Interventions

As emotionally and normatively loaded terms, sustainability and climate protection are frequently problematised within the politicised contexts of everyday research. This became especially apparent in interviews, workshops, and informal exchanges, where debates and comments commonly revolved around the legitimacy and appropriateness of proposed sustainability interventions. In the course of project-related discussions and discourse, fairly polarised conceptions tend to emerge, revealing themselves in the ways both academic and non-academic actors position themselves. To justify and legitimise their respective standpoints, actors frequently refer to broader political or societal contexts beyond the Living Lab itself. The polarised perspectives that emerge among academic and non-academic actors can be meaningfully distinguished through the lens of Weber’s ideal types of social action [81,82].

One pole of the spectrum is shaped by a value-rational orientation (wertrational) toward sustainability and climate protection—an orientation that informs and motivates individual collaborators in their everyday research practice, particularly when developing interventions. According to this normative view, climate protection measures should be implemented quickly, unconditionally, and regardless of resistance (‘no delay for climate changes’).

The instrumental-rational (zweckrational) view adopts a pragmatic counter-position, which states that climate protection measures should be carried out solely on the basis of consideration of the preconditions (‘climate protection takes time’). This perspective does not necessarily always correspond to the inner convictions and ambitions of the collaborators. Non-academic actors in particular tend to take greater account of the limitations arising from practical experience (e.g., financial or technological preconditions or cultural aspects) than academic actors. This also includes less willingness to take risks, owing to the fact that overly ambitious interventions pose a risk of excessive demands, strains on capacity, and overburdening.

Those guided by a value-rational orientation occasionally express impatience with the research process—especially when interventions are slow to materialise, or when their contributions are not adequately acknowledged by others. As a result, ever more tensions arise and sometimes culminate in conflicts when actors are faced with what they perceive to be irresponsible or unproductive resistance from other individuals or groups, who slow down the transformation or fail to grasp its necessity. In addition, the noble objective of climate protection provides a justification for increased enforcement of climate action, often causing overburdening, frustrations, and disengagement. In a similar vein, a number of studies have highlighted how sustainability is often accompanied by implicit normative expectations on researchers to ‘recognise and accept their social responsibility’ [83] (p. 67) and to commit themselves to transforming reality [84,85]. Furthermore, in their study on corporate sustainability studies, Van der Byl and Slawinski highlight how divergent understandings of sustainability, conflicting individual interests, and imbalanced emphases on sustainability dimensions can give rise to tensions and conflicts [32].

4.3. Difficulties in Role Positioning and Allocation

While a few roles were clearly defined and allocated at the beginning at the project (such as gate keepers, project leaders, assessment agents, and dissemination agents), the roles of non-academic and academic actors were largely left to fall into place over the course of the project. As the demands of each role emerge, actors seek out their preferred roles, or roles are ascribed to other actors—be it mutually, unilaterally, intentionally, or unconsciously. Furthermore, roles change over time, as a number of studies have highlighted [86,87,88].

In transdisciplinary settings, academic and non-academic actors alike are inevitably confronted with the challenge of navigating multiple roles and responsibilities [84,87,89,90]. In their systematic literature, Hilger et al. [41] identify fifteen roles of academic and non-academic actors assigned to four different realms (field, academia, boundary management, and knowledge co-production). They further distinguish the roles as originating from the field (actor groups) or adopted during research process. Mbatha and Musango [12] explore different stakeholders and their roles in Living Lab research within the energy sector. Based on an extensive literature analysis, they provide a detailed overview of these actors and their different roles.

For academic actors in particular, navigating and fulfilling the multiple roles associated with transdisciplinary collaboration proved to be a significant challenge in the course of everyday research. Throughout the interviews, academic actors repeatedly reflected on the dual role they feel pressured or obliged to fulfil in the context of the Living Lab—highlighting the tensions and ambiguities this role entails. This dual role comprises clusters of overlapping responsibilities, some of which are framed as forms of ‘activism’—thereby marking a distinction from conventional notions of academic research. Activities such as moderating and coordinating discussions and workshops, and informing, motivating, and advising non-academic actors, are subsumed under activism. In contrast, the collection, processing, and evaluation of data are considered pure research.

Although the majority of the researchers felt that they were well aware of the implications for their own role in view of the requirements for designing a Living Lab, the challenges only became apparent in the course of the research process. For example, the dual role fundamentally contradicted the self-image of individual academic actors from the outset, but was accepted as a small obstacle that could be overcome. As the need for ‘activist’ responsibilities became an ever-greater priority in cooperative experimentation in everyday research, the reluctance of individuals also grew. In extreme cases, research in the Living Lab is perceived as ‘fake research’. Tensions and even conflicts between academics and non-academics were just as much a consequence of this as frustrations. Felt et al. [46] (p. 522) describe the transdisciplinary research process as a ‘research borderland’ for academic actors. This conclusion may reflect the strong focus on academic actors in studies of roles in transdisciplinary research, with multiple studies highlighting the struggle of researchers with different roles in this context [25,87]. In their study on designing real-world laboratories for sustainable urban transformation, Huning et al. point to the difficult task actors face in understanding which role to fulfil at a certain moment [36] (p. 1599). By analysing the socialisation of early-stage researchers, Felt et al. describe the difficulties in developing roles, finding a position, and setting up transdisciplinary research lives [46] (p. 519). Focusing on sustainability transitions Bulten et al. [22] analyse the conflicting roles of researchers. They identified five potential roles, ranging from ‘reflective scientist’ to ‘transition leader’, and the tensions and conflicts that emerge when combining roles. Tensions arise from the following ‘three underlying sources: (1) researchers’ self-perception and expectations, (2) expectations of transdisciplinary partners, funders and researchers’ home institutions and (3) societal convictions about what scientific knowledge is and how it should be developed’ [22]. In a similar way, Pajot et al. analysed how researchers adopt multiple and changing roles in sustainability science projects in France. They explore the influence of stakeholder engagement, the need for role flexibility and adaptability of researchers, as well as a need to tailor roles to project characteristics [91].

Within the context of our research case study, the interviews revealed concerns about the virtually unlimited demands for role flexibility and adaptability placed on researchers. Only a ‘jack-of-all-trades’ could possibly handle all of the demands of the roles at hand. First, this points to the lack of skills all actors attribute to themselves and other collaborators. The skills necessary for multiple roles often extend to the skills needed in traditional empirical research (cf. [36]) (p. 1599). Similarly, Wiek et al. highlight the researchers’ lack of skills and identified five key competencies which should be combined and integrated [88]. Second, this is indicative of the uncertainties and frustrations in everyday research, particularly in the context of general time constraints. Third, this points to the willingness to adapt to unfamiliar roles. Several studies have highlighted personality as a potential driver of researchers’ roles [91,92]. Each of the three aspects increases the risk of disengagement on the part of either academic or non-academic actors.

4.4. Emergence of Instrumentalisation and Over-Identification

The sustained joint interactions in the Living Lab gradually cultivate familiarity and mutual empathy between collaborators, a process unanimously regarded by interviewees as a positive driver of collaboration in day-to-day research practice. This closer rapport and mutual empathy among the cooperation partners can also prove to be disadvantageous. Both academic and non-academic actors reported frustrations, tensions, and sometimes conflicts as a result of situations they felt were instrumentalised by their collaborators.

Instrumentalisation does not necessarily entail negative connotations. In our case, for instance, certain roles within the Living Lab were deliberately allocated during the design phase as part of the project’s structural setup. Roles such as gate keepers, dissemination agents, and communicators were assigned, or at least predefined. Moreover, academic actors who willingly embrace their activist role often perceive themselves—somewhat compliantly—as service providers for the non-academic partners. A similar observation is reported by Felt et al. in their study on participation in sustainability research projects [73] (p. 18).

In our case, the challenges of instrumentalisation relate mainly to the relationship between academic and non-academic actors. Situations were recounted in which tasks or responsibilities were passed on to ‘the others’—or unsuccessful attempts to do so were made. At the same time, instrumentalisation is attributed to individuals on both sides, around whom tensions then revolve. That even initial efforts at reallocation are met with scepticism reveals a pronounced sensitivity and alertness among the various actor groups involved. It is important to note that all collaborators are simultaneously confronted with limited resources and time constraints, which legitimises the reallocation of tasks the further the research project progresses.

The emergence of instrumentalisation often appears to be accompanied by a process labelled as ‘going native’. This term, as used within ethnography and anthropology, is the phenomenon of losing one’s research role and becoming totally immersed in the culture or group of people with whom one is collaborating [93,94]. This goes beyond the perceptions mentioned above of academic actors as service providers. In rare cases, they perceive themselves as members of the non-academic groups or organisation. Similarly, Hilger et al. [41] identify instances of the researchers adopting roles from the field as a step beyond the duality of practitioner and researcher.

Moreover, most of the academic actors consciously accept being instrumentalised and strategically deployed in service of the project’s objectives and its real-world application. Legitimising interventions or problematising sensitive issues is broadly seen as a mandatory function to fulfil. Likewise, Marg and Theiler point to the legitimising role of researchers and their instrumentalisation by the municipal administration within the transdisciplinary project [95] (p. 641).

4.5. Embedded Complexities of Living Lab Governance

In principle, and in line with the concept of participation, the governance as well as the creation of the Living Lab infrastructure is a joint endeavour. The way in which responsibility for governing the Living Lab project is distributed is therefore shaped by the modes of participation that the actors intentionally or unintentionally created. The governance process within the investigated Living Lab was frequently problematised as a form of ‘muddling through’ the everyday challenges of collaborative research.

Governance represents the culmination of challenging reactions in collaboration. First, heterogeneous interpretations of key Living Lab concepts, heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, difficulties in role positioning and allocation, and the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification might be considered as failed management on the part of the project leaders. In our case study, and as highlighted above, challenging reactions were sometimes attributed to individual leaders. Second, reactions such as tensions and conflicts call for mitigation measures, which themselves might account for uncertainties or overburdening. Third, both academic and non-academic actors identified a vast series of difficulties—all broadly related to the proto-challenges described above. These difficulties can be categorised based on varying core requirements in day-to-day practice.

- Managing participation and co-creation:

- Unfamiliarity with and lack of experience of project management built on the principles of transdisciplinarity and participation

- Difficulties in balancing and integrating the different interpretations of key concepts, as well as aspirations of sustainability

- Difficulties in balancing and integrating the different disciplinary and real-life set-ting perspectives (cf. [21])

- Managing needs, ideals, roles and expectations:

- Permanent need for project adaptation with multiple actors and organisations

- Balancing expectations (e.g., on participation, innovation and results) with practical conditions and possibilities

- Balancing conflicting ideals and practical needs

- Balancing the need for creative freedom with the need to reduce complexity

- Managing limitations, openness and unknowns:

- Lack of resources and time constraints in general (cf. [73])

- Difficulty in maintaining conceptional openness to new topics in the research process alongside the demands for stability and predictability in the Living Lab

- Difficulty in dealing with the effects of unintended interventions or unforeseen ex-ternal events (e.g., crises and political and regulative changes) on the experiments

One additional challenge emerged over the extended course of the project. Due to their aim of enabling sustainable innovation, Living Labs are often designed as a long-term initiative over several years [96]. In our case study, the timespan for the long lab was initially set for three years and was subsequently extended for a further two years. The long duration of the project and the diversity of the players involved are also accompanied by a natural fluctuation of collaborators. The recruitment of several new academic and non-academic collaborators initially disrupted the dynamics of individual Living Lab experiments, temporarily overburdening the existing interaction partners during the integration process. Engels and Rogge likewise identify similar destabilising dynamics, particularly in relation to shifting actor constellations and evolving role expectations within transdisciplinary collaborations [28].

5. Discussion

In our analysis, we identified uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts, and disengagement as challenging reactions in everyday Living Lab collaboration, as well as symptoms of five interrelated proto-challenges, which are as follows: (1) heterogeneous interpretations of key Living Lab concepts, (2) heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, (3) difficulties in role positioning and allocation, (4) the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and the culmination of these challenges, leading to (5) complexities in Living Lab governance. We argue that these proto-challenges are not incidental, but constitutive and implicitly inscribed into the key design principles of sustainability Living Lab research. This assumption finds support in various theoretical approaches that help illuminate the structural and processual dynamics of sustainability-oriented Living Lab research.

First, the proto-challenges thrive on the fertile ground of diverse institutional logics, power structures and dependencies, organisational structures, networks, and capacities for actions [24,71,74]. Institutional logics refer to culturally embedded meaning structures that define what is considered appropriate, legitimate, and purposeful within institutional settings—shaping, in turn, how time, space, roles, and resources are configured in the everyday research practice.

Second, when viewing Living Labs as transformation infrastructures, collaborative innovation is constrained or facilitated by ‘constitutive tensions’ [9]. Referring to the concepts of continuity and contingency, Schikowitz et al. [9] (p. 63) point to inevitable political, ideological, and epistemic tensions in synthesising traditions (conventions, perspectives, and knowledge), and innovations (disruption and inclusion) into the infrastructures of Living Labs. Comprising organisational, material, technical, and symbolic aspects, the Living Lab infrastructures are ‘permanently institutionalised and innovated’. Felt et al. [73] similarly identified tensions inherent in participatory research in an earlier study on sustainability research. From this perspective, Living Lab governance is equally subject to the same polarity.

Third, the proto-challenges manifest in the collectively constructed perception of goal conflicts. A prominent example of this is the tension between procedural efficiency and participatory aspirations, which emerged as a central governance dilemma in the Living Lab under study. This aspect opens a conceptual link to Paradox Theory, which focuses on the simultaneous presence of contradictory but interdependent elements, which are paradoxical tensions that persist over time. Unlike conventional goal conflicts that call for resolution, paradoxes invite coping strategies aimed at embracing and leveraging tensions as generative forces—an approach particularly relevant in the context of sustainability-oriented Living Lab governance [78,79,80].

Following the thesis that constitutive tensions “cannot be resolved but must be processed” [9] (p. 62), the question arises as to which coping strategies should be applied. Based on our case study and recommendations in the scientific literature on challenges in transdisciplinary research, we distinguish between the following three ‘ideal-typical’ coping strategies, categorised according to their mode of action: mitigate, embrace, and tolerate (Figure 5). The following section outlines the strategies in terms of their function, practical application, and potential risks.

Figure 5.

Overview—proto-challenges, challenging reactions, and coping strategies.

5.1. Mitigate Challenges

The mitigation approach focuses on preventing challenging reactions, as well as proto-challenges, by employing design and management tools that address the governance or infrastructure of the Living Lab. A vast number of studies examining challenges, barriers, and tensions in sustainability and transdisciplinary research provide recommendations or guidelines for mitigation. Examples include general design principles [21,24]; principles for balancing team compositions [97], skills [88], or roles [63,64]; and coping strategies for conflicts [32], quality, or evaluation criteria [29,30]. Mitigation measures favour consensus, harmony, and compromises, demanding awareness and resources at the same time. Both aspects are often outsourced to external experts providing feedback such as coaching or supervision [98,99]. By privileging continuity over contingency, mitigating strategies carry the risk of limiting innovation.

In the investigated case, the mitigation approach represents the dominant strategy—manifesting both at the level of project governance and within the discourse on participatory problem definition. Considerable effort was often invested in the formulation of identified barriers to experimentation, to avoid unsettling any organisational unit, responsible actor, or decision-maker. Another mitigating measure involved adjusting the recruitment profile. In light of the high demands regarding role performance and positioning—as well as the previously described staff turnover—the focus has shifted toward recruiting more experienced researchers in transdisciplinary or sustainable science.

5.2. Embrace Challenges

This approach stems from the perspective that certain tensions cannot be resolved but need to be embraced permanently [9,28,100]. The embracement view emphasises the constructive possibilities of contingencies as a source of innovation and represents a paradoxical approach which accepts and explores tensions rather than resolutions [25]. Indeed, it encourages actors to ‘host the tensions and the associated inconsistencies’ [28] (p. 31). As a rather unintuitive strategy, it allows for contingencies and dissonance, perhaps even provoking unplanned encounters, settings, irritations, or confrontations. Sufficient awareness among the actors and transparent proceedings and resources are prerequisites of this approach. By privileging contingency over continuity, embracing strategies carry the risk of destructive escalation or withdrawal.

While the embracement approach was the least prevalent strategy in the investigated case, it was nonetheless observable in isolated instances. For example, during a leadership workshop spanning multiple hierarchical levels, as well as in a company-wide survey, employees expressed concerns about the absence of a coherent climate strategy. The corporate leadership, however, interpreted the issue not as a strategic gap but as a matter of insufficient implementation and internal communication. This tension was addressed, first through the initiation of a participatory process aimed at developing everyday action guidelines. This approach fostered intra-organisational discourse on climate protection activities and strengthened the connection between the overarching climate strategy and day-to-day practices. Second, the problematisation of the existing climate strategy helped to trigger a process in which binding greenhouse gas reduction pathways are defined for both the city administration and the individual enterprises within the corporate city.

5.3. Tolerate Challenges

The tolerance strategy entails a reflective engagement with collaborative tensions by maintaining an observant stance without resorting to immediate intervention. Rather than suppressing or resolving such challenges, this approach advocates for their conscious acknowledgment and containment, allowing actors to remain responsive without being reactive. Similar to the embracement approach, this strategy unintuitively accepts irresolvable contradictions and allows for ‘agonism’ [9,101,102,103,104]. It should be emphasised that this strategy should not be misunderstood as a consequence of disengagement by Living Lab actors. Like the embracement approach, it too allows for contingencies and dissonance. In addition to sufficient awareness, the approach requires tolerance for organisational slack, as well as joint understanding on why mitigation measures are not taken. Tolerating challenges and reactions carries the risks of both alternative approaches—limiting innovation and enabling destructive escalation or withdrawal.

Within the project, the tolerance approach emerged as a viable course of action in response to disengagement processes—particularly among non-academic actors.

6. Conclusions

Sustainability research addresses the complexities of the significant challenges facing contemporary societies [73]. As a tool for sustainability, Living Lab research challenges given assumptions, imaginations, and expectations on the part of collaborators. Challenging reactions such as uncertainties, frustrations, overburdening, tensions, conflicts, and disengagement is an inevitable part of everyday collaboration in Living Labs. These are emphatically an inherent tendency given the heterogeneous interpretations of key Living Lab concepts, the heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions, the difficulties in role positioning and allocation, the emergence of instrumentalisation and over-identification, and the embedded complexities of Living Lab governance, which both constrain and enable innovation.

Coping with these (proto-)challenges can appear to be a daunting task. Mitigating challenges and reactions carries the risk of limiting innovation, embracing tensions carries the risk of destructive escalation, while tolerance involves both risks. Wicked problems are defined as impossible to solve because of incomplete, ambiguous, contradictory, and fluctuating demands. Against this backdrop, collaborative sustainability research in Living Labs appears as a wicked problem in itself.

Accordingly, no blanket recommendations for practical application can be derived. Rather, our study underscores the importance of awareness, preparedness, and resilience among Living Lab research actors in navigating the constitutive challenges of collaboration. In this context, we highlight the potential of less intuitive coping strategies—such as embracing and tolerating these constitutive tensions. Both strategies would undermine the ‘tendency towards continuity’ of academic actors that Schikowitz et al. identify in their study of two Living Labs on urban mobility in Austria [9] (p. 71). Embracing and tolerating contingencies are unintuitive approaches and require effort, transparent processes, and a joint understanding. We further argue with Schikowitz et al. that ‘meeting the various demands and expectations that policy makers and researchers amount on living labs is, in fact, a mission impossible’ [9] (p. 72). Hence, our results may foster knowledge and understanding of the unavoidable challenges in everyday Living Lab research.

In considering heterogeneous interpretations of key Living Lab concepts and heterogeneous perspectives on sustainability interventions as inevitable, as well as a source of contingencies and innovation, we find ourselves caught in a dilemma. On the one hand, we would be keen to argue for further scientific research on quality standards for the design and implementation of Living Lab infrastructures and governance. On the other hand, the harmonising or standardisation of Living Lab infrastructures as a mitigation tool would prevent the contingencies needed for innovation.

The limitations of our study are primarily epistemological. First, our single-case design challenges the potential for generalisations, as we assume constitutive proto-challenges as typical of Living Lab research. By relating our results to other contemporary studies, we have attempted to provide validity for our arguments beyond our case study. Nevertheless, additional investigations into multiple case studies are strongly recommended. Furthermore, cross-cultural comparisons would allow for the generalizability of proto-challenges to be tested. Future studies should focus notably on differences in project characteristics, as well as sampling criteria.

Second, our involvement as researchers as well as collaborators within the Living Lab case carries the risk of biased interpretations, particularly in light of the previously described processes of over-identification and instrumentalisation. Although we addressed this through systematic reflection and team-based interpretation, the possibility of bias cannot be entirely ruled out. The support or assignment of external researchers in future work would help mitigate that risk. At the same time, however, it would limit opportunities for participation in everyday Living Lab practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, W.K.; methodology, W.K. and L.S.; validation, W.K., formal analysis, W.K.; investigation, W.K. and L.S.; resources, S.L.; data curation, W.K. and L.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.K. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, W.K.; visualisation, W.K.; supervision, S.L.; project administration, S.L.; funding acquisition, S.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Research and Art of the German Federal State Baden-Württemberg within the scope of the research project ‘Klima RT LAB’.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is waived for ethical review as it was conducted according to the guidelines of the Code of Ethics of the German Sociological Association, which ensure the principles of avoiding harm, maintaining anonymity and confidentiality, and informed consent.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thollander, P.; Palm, J.; Hedbrant, J. Energy Efficiency as a Wicked Problem. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryshlakivsky, J.; Searcy, C. Sustainable development as a wicked problem. In Managing and Engineering in Complex Situations; Kovacic, S.F., Sousa-Poza, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 21, pp. 109–128. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; De Haan, H. Transitions: Two steps from theory to policy. Futures 2009, 41, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchman, C. Free for All. Wicked problems. Manag. Sci. 1967, 14, B141–B142. [Google Scholar]

- Bakıcı, T.; Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. A Smart City Initiative: The Case of Barcelona. J. Knowl. Econ. 2013, 4, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballon, P.; Schuurman, D. Living labs: Concepts, tools and cases. Info 2015, 17, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergvall-Kåreborn, B.; Eriksson, C.I.; Ståhlbröst, A. Places and Spaces within Living Labs. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2015, 5, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Caniglia, G.; Schäpke, N.; Lang, D.J.; Abson, D.J.; Luederitz, C.; Wiek, A.; Laubichler, M.D.; Gralla, F.; von Wehrden, H. Experiments and evidence in sustainability science: A typology. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schikowitz, A.; Maasen, S.; Weller, K. Constitutive Tensions of Transformative Research: Infrastructuring Continuity and Contingency in Public Living Labs. Sci. Technol. Stud. 2023, 36, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission 2022: Launch Event of Flagship 7 of the European Commission’s Zero Pollution Action Plan. Brussels. 2022. Available online: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/living-labs-heart-zero-pollution-action-plan (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Dekker, R.; Contreras, J.F.; Meijer, A. The Living Lab as a Methodology for Public Administration Research: A Systematic Literature Review of its Applications in the Social Sciences. Int. J. Public Adm. 2020, 43, 1207–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbatha, S.P.; Musango, J.K. A Systematic Review on the Application of the Living Lab Concept and Role of Stakeholders in the Energy Sector. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Osborn, J.; Martiskainen, M.; Lipson, M. Testing smarter control and feedback with users: Time, temperature and space in household heating preferences and practices in a Living Laboratory. Glob. Environ. Change 2020, 65, 102185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M.; Nyström, A.-G. Living Labs as Open-Innovation Networks. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2012, 2, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Feurstein, K.; Hesmer, A.; Hribernik, K.; Thoben, K.D.; Schumacher, J. Living Labs–A New Development Strategy. In European Living Labs—A New Approach for Human Centric Regional Innovation, 1st ed.; Chapter 1; Schumacher, J., Ed.; wvb, Wiss. Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.; Leminen, S.; Westerlund, M. A systematic review of living lab literature. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 213, 976–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S.; Nyström, A.-G.; Westerlund, M. A typology of creative consumers in living labs. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2015, 37, 6–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almirall, E.; Wareham, J. Living Labs: Arbiters of Mid- and Ground-Level Innovation. In Global Sourcing of Information Technology and Business Processes; van der Aalst, W., Mylopoulos, J., Sadeh, N.M., Shaw, M.J., Szyperski, C., Oshri, I., Kotlarsky, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 55, pp. 233–249. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze, U.; Boland, J.R., Jr. Place, space and knowledge work: A study of outsourced computer systems administrators. Account. Manag. Inf. Technol. 2000, 10, 187–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groß, M. Realexperimente: Ökologische Gestaltungsprozesse in der Wissensgesellschaft, 1st ed.; Transcript: Bielefeld, Germany, 2005; Available online: https://www.degruyter.com/isbn/9783839403044 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Nesti, G. Living labs: A new tool for co-production? In Smart and Sustainable Planning for Cities and Regions; Bisello, A., Vettorato, D., Stephens, R., Elisei, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- Bulten, E.; Hessels, L.K.; Hordijk, M.; Segrave, A.J. Conflicting roles of researchers in sustainability transitions: Balancing action and reflection. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1269–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S.; Büscher, C.; Hessels, L.K. Towards Transdisciplinarity: A Water Research Programme in Transition. Sci. Public Policy 2018, 45, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7 (Suppl. S1), 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.G. The challenging role of researchers coping with tensions, dilemmas and paradoxes in transdisciplinary settings. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 30, 326–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leminen, S.; DeFillippi, R.; Westerlund, M. Paradoxical tensions in living labs. In Proceedings of the XXVI ISPIM Conference–Shaping the Frontiers of Innovation Management, Budapest, Hungary, 14–17 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hakkarainen, L.; Hyysalo, S. How Do We Keep the Living Laboratory Alive? Learning and Conflicts in Living Lab Collaboration. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2013, 3, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Engels, A.; Rogge, J.C. Tensions and Trade-Offs in Real-World Laboratories–The Participants’ Perspective, Gaia; Oekom: Munich, Germany, 2018; Volume 27, pp. 28–31. [Google Scholar]

- Blackstock, K.; Kelly, G.; Horsey, B. Developing and applying a framework to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 60, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahn, T.; Keil, F. An actor-specific guideline for quality assurance in transdisciplinary research. Futures 2015, 65, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plummer, R.; Blythe, J.; Gurney, G.G.; Witkowski, S.; Armitage, D. Transdisciplinary partnerships for sustainability: An evaluation guide. Sustain. Sci. 2022, 17, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Byl, C.A.; Slawinski, N. Embracing tensions in corporate sustainability: A review of research from win-wins and trade-offs to paradoxes and beyond. Organ. Environ. 2015, 28, 54–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerlund, M.; Leminen, S. The multiplicity of research on innovation through living labs Paper presented at the XXV ISPIMConference. Dublin, Ireland, 8–10 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Herrera, N. The emergence of living lab methods. In Living Labs; Keyson, D.V., Guerra-Santin, O., Lockton, D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Baran, G.; Berkowicz, A. Sustainability Living Labs as a Methodological Approach to Research on the Cultural Drivers of Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huning, S.; Räuchle, C.; Fuchs, M. Designing real-world laboratories for sustainable urban transformation: Addressing ambiguous roles and expectations in transdisciplinary teams. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1595–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Jiménez-Aceituno, A.; Lam, D.P.; Bürgener, L.; Lang, D.J. Transdisciplinary learning as a key leverage for sustainability transformations. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2023, 64, 101361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerari, E.; De Koning, J.I.J.C.; Von Wirth, T.; Karré, P.M.; Mulder, I.J.; Loorbach, D.A. Co-Creation Dynamics in Urban Living Labs. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menny, M.; Palgan, Y.V.; McCormick, K. Urban Living Labs and the Role of Users in Co-Creation. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2018, 27, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.H.; Thomas, E. Ideologies in Energy Transition: Community Discourses on Renewables A Review of Living Lab Research Development and Methods for User Involvement. Technol. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2021, 11, 88–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, A.; Rose, M.; Keil, A. Beyond practitioner and researcher: 15 roles adopted by actors in transdisciplinary and transformative research processes. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 2049–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brankaert, R.; Ouden, E.D.; Brombacher, A. Innovate dementia: The development of a living lab protocol to evaluate interventions in context. Info 2015, 17, 40–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]