1. Introduction

Spanning nine administrative regions—Qinghai, Sichuan, Gansu, Ningxia, Mongolia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, and Shandong—the Yellow River, China’s second largest fluvial system, functions as a pivotal provenance of Chinese culture and history and is a vital economic sector. Moreover, the river, symbolic of the origins of Chinese culture, holds significant cultural assets and tourism resources in its basin area, profound historical and traditional cultural foundations, rich natural ecological landscapes, and distinct ethnic and regional characteristics. The Yellow River Basin, which comprises 36.9% of the national basin area, contains 20 world heritage sites, 300,000 immovable cultural relic resources, and 84 national 5A-level tourist attractions in China. Cultural–tourism industrial development within the Yellow River Basin holds pivotal strategic significance for China’s “cultural power” strategy and overall industrial construction system. Recently, China has paid a high level of attention to the Yellow River Basin’ cultural heritage and tourism development, and the quality–efficiency synergy in tourism and cultural industry integration has become instrumental in fostering industrial renewal in the Yellow River Basin. In September 2020, General Secretary Xi Jinping proposed a development strategy for “building the main historical and cultural landmarks of the Yellow River while ensuring ecological conservation, and facilitating symbiotic growth between culture and tourism, the ‘dual engines’ in the Yellow River Basin.” In October 2021, the “Outline of the Plan for Ecological Protection and High Quality Development of the Yellow River Basin” proposed the strategic deployment of “systematically protecting the cultural heritage, inheriting and promoting the spirit and culture, promoting the integrated tourism–culture development, building the cultural-tourism industry into a pillar industry, and constructing a number of iconic tourist destinations showcasing the Yellow River culture,” as well as the strategic goal of “creating an internationally influential Yellow River cultural tourism belt,” again promoting tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin. This agglomeration, however, remains at an incipient phase, and industrial development and integration are uneven across regions. Furthermore, factors that affect the collaborative agglomeration of industries remain unclear. Therefore, the transformation and upgrading of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries make it imperative to clarify the spatiotemporal characteristics of their collaborative agglomeration and to assess the factors influencing their collaborative agglomeration, underpinning efforts toward regional integration and advancement equilibrium in the basin.

Several studies on industrial collaborative agglomeration have manifested that industrial collaborative agglomeration necessitates industrial correlation, and the factors influencing this collaborative agglomeration have been analyzed. Wood [

1] found that “collaborative agglomeration” tends to occur among industries that have similarities and expandable industrial boundaries. As industries engage in dialog and cooperative activities, collaborative agglomeration takes shape. The cultural and tourism sectors are strongly correlated in their development processes. Through its ability to spread and commercialize culture, tourism stimulates the cultural industry, which in turn lays the foundation for the stable and sustainable growth of tourism. Much previous research on the synergistic agglomeration of tourism and cultural industries has focused on analyzing how cultural engagements [

2], products [

3], and festival events [

4] impact sectoral development. Studies have shown a strong tourism–culture correlation during development, and their development is affected by industrial resources, local customs, and human resources [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Using the cultural and tourism sectors as examples, Hughes et al. [

9] explored how industrial boundaries tend to blur during the formation of collaborative agglomerations. Their study showed that tourism and cultural industries’ industrial boundaries gradually blur during the course of agglomeration development. The integration of resources and market demand for integrated products can promote industrial integration, and industrial resources and markets are key factors in promoting collaborative industrial agglomeration. Nurse et al. [

10] focused on Brazil to understand how festival activities contribute to the co-development of tourism and cultural sectors. Their study showed that festival activities can stimulate industrial synergy between culture and tourism and act as a driver for local economic sustainability. Shepherd et al. [

11] used the Korean tourism and cultural industries to confirm the correlation inter se and analyzed the impact of such factors as industry, human resources, market, and government on the spatial structure of the industry. Their study showed that more efficient spatial alignment of tourism and cultural industries not only aids regional progress but also yields greater returns in less urbanized locations. Thus, with multiple factors shaping inter-industry collaborative agglomeration dynamics, a well-grounded selection of these influences is essential for analyzing related issues and boosting industrial collaborative agglomeration development.

With the continuous deepening of the industrial economy, several scholars have turned to analyzing industrial spatiotemporal pattern evolution characteristics to address the problem of uneven economic development in various regions [

11,

12,

13]. Niu et al. [

14] analyzed the relationship between the industrial spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and urban clusters’ expansion characteristics, showing that the spatial structure of industrial clusters gradually expands from central to peripheral cities over time. The rationalization of industrial spatial results propels regional development and has more significant effects on less urbanized cities. Bosch et al. [

15] probed into the spatiotemporal pattern characteristics of urban agglomeration expansion from an industrial perspective, positing that the expansion of industrial spatial patterns can drive the expansion of urban agglomerations outward, thereby alleviating problems such as population density and resource scarcity in these areas. Informed by a qualitative investigation into the structural linkage of tourism and cultural sectors in the Chinese context, Peng et al. [

16] examined the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of tourism and cultural industries. Their study showed that coupling between the Chinese tourism and cultural industries is generally low, exhibiting a spatial layout of being “lower in the east and west than in the southeast.” Li et al. [

17] used spatial displacement analysis to examine the spatial layout and displacement degree to which these distributions have shifted in tourism and cultural industries across China. Their study showed clear regional disparities in how tourism and cultural industries have developed in China, highlighting that the development of these industries is uneven among provinces. The interprovincial spatial displacement associated with the tourism and cultural industries has been decreasing annually. A growing tendency within China’s industrial sphere is tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration, and the spatial distribution of industries exhibits intimate associations with the economic development level and the direction of urban agglomerations. Therefore, a rational spatial layout of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries is crucial for boosting balanced regional development and achieving an agglomerated economy.

However, influenced by the economic levels of various regions, significant differences exist in the levels of coordinated agglomeration of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries. Clarifying the regional spatiotemporal pattern evolution characteristics of the tourism and cultural sectors can help boost the balanced development of these industries in the area. Furthermore, various factors influence tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration. Clarifying these factors is key to boosting collaborative agglomeration development. However, there are still pronounced regional discrepancies in the Yellow River Basin’s cultural and tourism development, with a clear research gap in the analysis of its spatiotemporal evolution. Moreover, qualitative analysis was predominantly employed in previous research on the factors influencing tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration, and a quantitative analysis of these factors is lacking. Taking the Yellow River Basin as the focal region and adopting a synergetics-based framework with a dual focus on time and space, this study first applies a spatial autocorrelation test to assess the evolution of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration, clarifying the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of these industries in various regions of the area. Then, the spatial Durbin model (SDM) is deployed to quantitatively assess the influencing variables of tourism–culture synergistic agglomeration and to determine the internal mechanisms of each influencing factor. Finally, informed by the observed spatiotemporal patterns and influencing factors, countermeasures and suggestions are proposed to boost their quality–efficiency synergy integration and development.

2. Theoretical Framework and Method

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Tourism–culture synergy, supported by their upstream–downstream alignment, enables transformation and upgrading and expands the industrial value chain in both vertical and horizontal dimensions, thereby forming a more stable industrial structure. The key to boosting collaborative agglomeration plus the quality–efficiency synergy of tourism and cultural sectors lies in the clarification of their spatiotemporal agglomeration trends and the analysis of key determinants and causal mechanisms. Therefore, the present work, framed by synergetics and centered on the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries, analyzes the spatiotemporal evolution of their collaborative agglomeration and identifies the internal mechanisms of its driving factors. Synergetics mainly emphasizes that during industrial development, synergy and self-organization among industries promote the evolution of industries from disorder to an orderly structure [

18]. It recurs during the course of forming the collaborative agglomeration effect by means of resource allocation, market promotion, talent collaboration, and policy integration. During the course of synergistic agglomeration of the Yellow River Basin’ tourism and cultural industries, driven by external factors such as policies, markets, and innovative technologies, the tourism and cultural industries are able to not only boost the interaction of non-linear factors like industrial resources, economic factors, and labor force to generate order parameters but also boost the evolution of the tourism and cultural industrial structure from disorder to order. This is also the self-organization process of industrial elements during tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the basin. The theoretical analysis framework underlying the present work is graphically illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. Method

2.2.1. Spatial Autocorrelation Test Model

To determine whether spatial relationships exist among variables, researchers often use the spatial correlation model, which comprises global and local Moran’s I for autocorrelation and cluster–outlier analysis, respectively.

(1) Global Moran’s I was adopted here to explore the aggregate spatial dependence between the tourism and cultural industries. Its mathematical representation is given below:

where

is the global spatial autocorrelation (GSA) index for the region’s tourism and cultural industries.

indicates the sample size.

is a standardized element, with its value being a weight matrix element.

and

refer to the observation values of regions

and

, respectively.

stands for the mean observed value of variable

.

, a spatial weight matrix (SWM), represents the relationships between spatial data. In the context of Moran’s I

, Moran’s I > 0 signifies agglomeration (positive spatial correlation), Moran’s I < 0 implies dispersion (negative correlation), and Moran’s I = 0 indicates no spatial dependence between tourism and cultural industries.

(2) Local Moran’s I was employed to examine the local tourism–culture linkage. Its equation is presented below:

where

captures the spatial dependence of tourism and cultural industries in

.

is the observation data for region

.

corresponds to the observation data of its neighboring region

.

captures the overall variability in the variable being analyzed for region

.

establishes how each region is spatially related to others in the analysis.

stands for the global mean of the observed variable

. A Moran scatter chart is deployed to generally present the results of local Moran’s I, comprising four quadrants that reflect the spatial relationship between each unit and its neighbors: H–H (regions with high values near other high-value areas), L–H (low-value regions surrounded by high values), L–L (low values adjacent to other low values), and H–L (high-value regions adjacent to low-value neighbors).

2.2.2. SDM

As a spatial econometric technique, the SDM is deployed to describe the relationships between different feature variables and their features in high-dimensional space. This method involves non-linear processing of data, mapping the raw data to a high-dimensional spatial model, and analyzing the spatial relationship between independent and dependent variables [

19,

20]. The SDM framework enables simultaneous assessment of the spatial dependence of different regions and spatial spillover effects. Simultaneously, the SDM is subjected to partial differentiation processing, which can decompose spatial dependence into direct and indirect effects, offering a basis to assess how various influencing variables impact the tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration degree (tourism–culture CAD) within the basin. The initial step in constructing the SDM involves building an SWM. To reflect both spatial proximity and economic disparity among regions, this study formulates two SWMs—geographic and economic distance matrices—grounded in the industrial profile of the basin’s tourism and cultural sectors, whose mathematical expressions are

Geographic distance matrix:

Economic distance matrix:

where

stands for the distance between regions

and

, and

stands for the mean of economic indicators between them. Following the establishment of the SWM, the construction of the SDM begins, whose mathematical expression is

where

stands for the level of tourism and cultural synergy in region

at time

, and

and

refer to the regression coefficient and the spatial adjacency matrix, respectively.

is the value of

influencing factors that affect the tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration in region

at time

.

stands for the regional effect of influencing factors,

corresponds to the time effect of influencing factors, and

is a random perturbation term.

To further explore the intrinsic processes driving tourism–culture synergistic agglomeration and to distinguish between direct and spillover effects of each affecting factor, this study applies a partial differentiation method based on the framework of Yang et al. [

21] to Equation (5). The mathematical formula for the SDM after partial differential processing is as follows:

The linkage between the explanatory variable

and the explained variable

is captured through the following matrix of partial derivatives for the model’s predicted output:

The direct and indirect impacts of the factors affecting the synergistic agglomeration of the cultural and tourism industries in the Yellow River Basin on the degree of collaborative agglomeration are separately represented by diagonal averages and the average of off-diagonal row and column sums.

3. Spatial Scope and Data Selection

3.1. Spatial Scope

Among China’s main rivers, the Yellow River is the second longest river and the mother river of the Chinese nation. The Yellow River originates from the Bayannur Mountains in Qinghai Province and flows through nine provincial-level administrative regions, including Qinghai, Gansu, Sichuan, Shandong, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Ningxia, Henan, and Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. By referring to the “Hydrological Yearbook of the Yellow River Basin” and the region’s geographical definition, we selected 69 typical cities and ethnic minority autonomous prefectures in the Yellow River Basin as research areas, including Jinan, Zhengzhou, Taiyuan, Hohhot, Yinchuan, Lanzhou, Aba, Xining, etc., which have developed into an important corridor for cultural dissemination and tourism industry in China. With rich cultural and tourism resources, these regions are not only key areas for the development of the tourism industry within the Yellow River Basin but also important sectors for the coordinated development of China’s cultural and tourism industries. The location and detailed map of the typical area of the Yellow River Basin selected in this article are shown in

Figure 2.

This basin is home to rich cultural resources, and each region along the Yellow River has its own unique cultural industry development. The Yellow River Basin is affected by topography and landforms, resulting in significant geographical and climatic differences between regions. This has led to variations in natural landscapes and customs, as well as cultural atmospheres and intangible cultural heritage in different areas. Qinghai, Sichuan, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, and Gansu are gathering areas for ethnic minorities in China, exhibiting unique cultures and intangible cultural heritage. The cultural industries in these regions also rely on the development of ethnic minority cultures and intangible cultural heritage crafts. Shaanxi, Henan, Shanxi, Shandong, and other regions in China exhibit vibrant historical and cultural heritage. The cultural industries in these areas were also developed based on the combination of these historical cultures and historical buildings, as well as the rich red revolutionary culture in the areas of Shaanxi and Gansu and their vicinity. In the era of revolution, the Shaanxi–Gansu–Ningxia base area was also an important tourist attraction. The Yellow River Basin’s central and eastern regions displayed a well-developed cultural industry structure, along with a relatively developed industrial economy. The role of cultural resources in boosting the cultural industry is more significant. Owing to constraints by economic development, the Yellow River Basin’s western region exhibits relatively underdeveloped cultural industries. Cultural resources play a weak role in boosting cultural industries.

Figure 3 shows the cultural resource distribution across the basin.

Capitalizing on the uniqueness of its geographical landforms and cultural heritage, the Yellow River Basin possesses an extensive variety of natural landscapes, scenic spots, historical sites, and other tourism resources. Public sector institutions in different provinces have shown growing attention to tourism industry growth. Regions such as Shaanxi, Henan, and Shandong often rely on historical buildings and cultural heritage to develop tourism activities and tourist attractions. Shaanxi and Gansu have rich red revolutionary culture, and the Shaanxi–Gansu–Ningxia base area is also an important tourist attraction. Shanxi and Shandong Provinces have famous tourist attractions such as Mount Taishan and Mount Wutai, and the tourism industry in these areas is combined with unique natural landscapes. Subnational units like Ningxia, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia have unique ethnic minority cultures and natural landscapes in which the tourism industry relies on local ethnic customs and natural scenery.

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of tourism resources across the basin.

3.2. Data Selection

Quantitative assessment of the driving factors and space–time pattern changes in tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the Yellow River Basin is based on data obtained from the

Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Culture and Related Industries, the

Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Tourism, the

Statistical Yearbook of Chinese Culture and Tourism, and cultural and tourism-related yearbooks and regional bulletins from 2011 to 2021. Based on insights from Yang [

5], Zhou [

6], Li [

17], and Chi [

22], we conducted a systematic analysis on the collaborative agglomeration development of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries from six aspects: industrial economy, industrial policies, industrial innovation, industrial resources, human resources, and market demand. With respect to industrial resources, the tourism and cultural industries, as upstream and downstream industries, have strong correlation and integration in their industrial resources. Industrial resources play a critical role in fostering collaborative agglomeration, with sites such as museums and tourist attractions showing notable links to agglomeration intensity. The industrial economy’s consistent expansion provides a strong foundation for the sustained and healthy development of industries, and it is a crucial driving force for industrial coordinated agglomeration development, transformation, and upgrading. Industries’ added value and total income serve as not only pivotal factors for measuring the level of industrial economy but also vital indicators for industrial collaborative agglomeration. As to human resources, Weber’s research [

23] shows that labor is one of the pivotal factors impacting the tourism–culture CAD and their locational preferences. The quantity and allocation of employees in the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries also act as crucial players for the sustainable and healthy operation of the industries. Therefore, human-resource-related factors such as the employees in museums and tourist attractions play important roles in analyzing issues related to the coordinated agglomeration of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries. As to industrial policies, at the onset of industrial coordinated agglomeration, government support levels and policy intensity for the tourism and cultural industries serve as affecting factors for the development direction and production efficiency of these industries [

24]. As upstream and downstream industries, the tourism and cultural industries possess the capacity to benefit from government support, which can not only promote their stable development but also effectively guide their collaborative communication, thus driving their coordinated agglomeration development. Therefore, fiscal investment and its proportion in fiscal expenditure, as important indicators to measure the degree of policy support for these two industries, are also pivotal affecting factors for tourism–culture coordinated agglomeration development in the basin. Under economic sector classification adopted by China, tourism and cultural industries fall within the tertiary sector, producing products to satisfy individuals’ psychological and artistic requirements. Consequently, the consumption demand for touristic and cultural commodities serves as a pivotal determinant in the coordinated agglomeration of these industries. As to innovation resources, innovation resources and science and technology policies are favorable driving forces that influence the industrial structure and boost industry conversion and upgrading [

24]. Tourism and cultural industry professionals, along with associated research institutions, demonstrate the competence to generate a knowledge spillover effect by virtue of technological exchanges, talent flow, and so on, thereby promoting industrial transformation and upgrading. So, innovation resource factors are also essential for tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin. In the present study, grounded in the six aspects discussed earlier, an indicator system is constructed for factors influencing the collaborative agglomeration of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries (

Table 1). Regarding the spatiotemporal features of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration in the basin, relevant geographic information data utilized in the present work are from the National Standard Map Service System of China (

http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/, accessed on 19 June 2025).

4. Empirical Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Assessment of the Spatiotemporal Pattern Evolution Characteristics of Tourism–Culture Collaborative Agglomeration Within the Yellow River Basin

4.1.1. GSA Test

In the present work, we adopted the GSA test to evaluate how tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin has changed over both time and geographic space. The GSA test was implemented on 69 regions in the basin during the 2011–2021 period to assess tourism–culture interactions according to Equation (1). The findings are summarized in

Table 2.

The global Moran’s I values for the 2010 to 2019 period were negative at the specified confidence level, pointing to an inverse spatial relationship in tourism–culture agglomeration across the basin. The dynamic trend of Moran’s I over time unveiled that spatial synergy showed an “up–down–up” trend during the 2011–2021 period. The GSA index increased annually throughout this temporal phase. This is because China was experiencing rapid socio-economic development during the 2011–2014 period, and the tourism and cultural industries also exhibited moderate growth trajectories propelled by the social economy. Certain improvements were also noted in the tourism–culture CAD, but the GSA index slightly decreased from 2015 to 2017; however, they remained positively correlated. This is because this period was a stage of industrial structural transformation in China, and fluctuations in the industrial structure weakened tourism–culture spatial synergy within the basin. However, the spatial linkage between the two sectors retained its positive orientation, and the GSA index rebounded slightly from 2018 to 2021. This indicates that the Chinese Ministry of Culture and Tourism established in 2018 boosts the alignment of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries.

A GSA test was then completed on tourism–culture synergistic agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin. The GSA index for tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the area was also determined by the use of the same methodological approach. Grounded in the principles of the GSA index division and previous findings such as those of Chakraborty [

25] and Guo [

26], the standard for dividing the GSA degree of tourism–culture agglomeration within the basin is constructed (

Table 3).

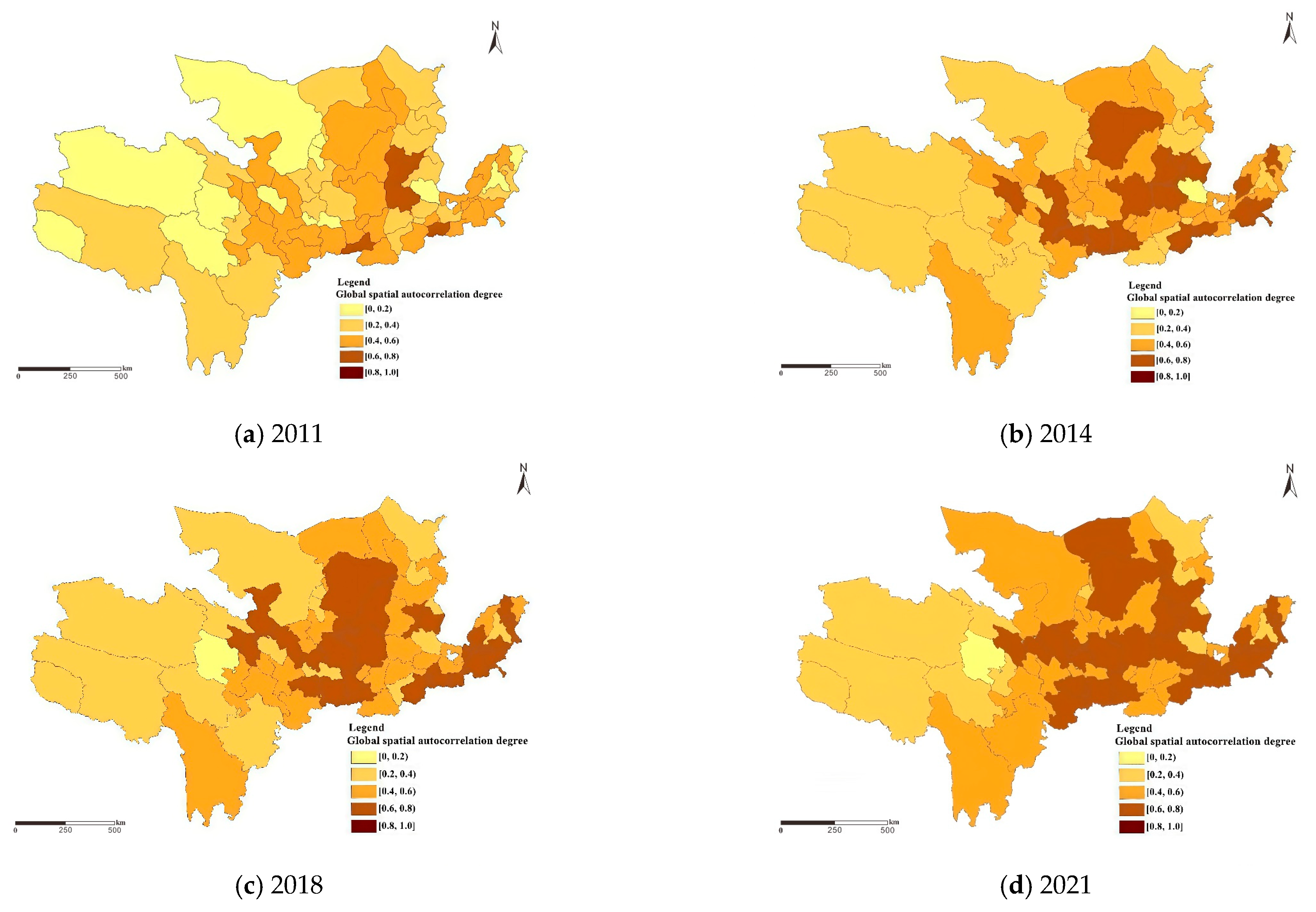

After calculating the GSA degree of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the basin, ArcGIS 10.0 software was utilized to visualize the GSA index of the tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration in this area. A fluctuating trend is evident in

Table 3, with 2014 and 2018 being the time nodes. Therefore, four time nodes in 2011, 2014, 2018, and 2021 were selected as examples to demonstrate the degree of GSA of the collaborative agglomeration of Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries from a spatial perspective (

Figure 5).

As unveiled by

Figure 5, tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the basin has undergone a spatially uptrend in GSA, and the observed GSA follows a gradient—higher in the east and center and lower in the west. During the 2011–2021 period, the spatial autocorrelation strength increased annually. In 2011, only 3 regions registered a high spatial correlation level (Moran’s I

), whereas by 2021, this increased to 17 regions (Moran’s I

), and the overall spatial autocorrelation degree in Taiyuan, Zhengzhou, Luoyang, Xi’an, Yan’an, and other regions was higher than 0.7.

Regarding spatial distribution characteristics, the GSA of the basin’s tourism and cultural industries demonstrates a clear high pattern in the east–central regions and a low pattern in the west, which can be explained by the superior economic development, complete infrastructure, and perfected excavation, protection, optimization, and promotion of tourism and cultural industries. More industrial cooperation and exchange also occurs between regions, and the overall spatial autocorrelation of the tourism and cultural industries across the basin’s eastern and central regions is relatively high. However, the western basin has yet to achieve comparable levels of economic advancement, with inadequate road transportation, limited commercial services, and underdeveloped facilities. Insufficient progress in the exploration, integration, and promotion of the tourism and cultural industries in the western region has become a key obstacle to achieving coordinated growth.

4.1.2. LSA Test

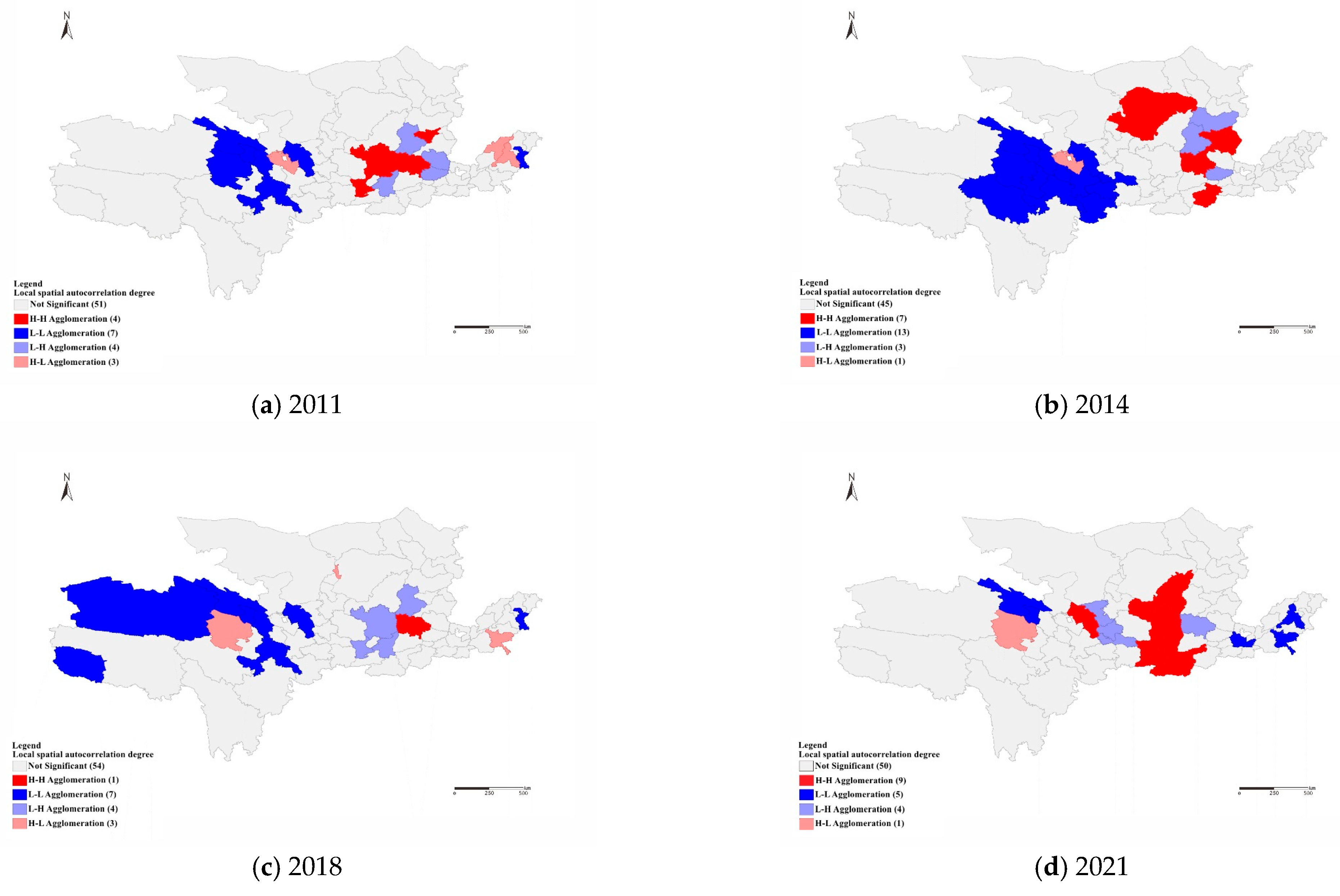

To further probe into the development features and spatial relationships of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin, ArcGIS software was deployed to implement an LSA test according to Equation (2). The results indicate tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin during the 2011–2021 period, with key transitions occurring in 2014 and 2018. Therefore, this study uses these time nodes for LSA testing. Clustering diagrams of the results for 2011, 2014, 2018, and 2021 are presented in

Figure 6.

As shown in

Figure 6, the degree of LSA between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries remains relatively low. At the temporal level, the correlation degree indicates a downward trend in “L–L” agglomeration areas, an upward trend in “H–H” areas, and relatively small fluctuations in “H–L” and “L–H” agglomeration areas. Such outcomes are associated with China’s economy, which underwent rapid development from 2011 to 2021, and the release of several policies to boost tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration, a concept originally introduced in China in 2009. Amidst the dual promotion by China’s fast-growing economy and national policies, the tourism and cultural industries in various Yellow River Basin regions progressed during the 2011–2021 period, and the correlation between both industries also improved. In turn, the collaborative agglomeration of both industries helped boost the growth and innovation of the industrial economy. Furthermore, the dual influence of economic externalities and knowledge transmission from industrial synergy also contributed to strengthening the linkage between tourism and cultural industries across the basin.

Evident regional imbalances exist in the LSA strength of tourism and cultural industries across the basin. Both a region’s own industrial capacity and that of neighboring regions play roles in shaping this outcome. In cities such as Xi’an and Yan’an—representing the eastern and central regions—the tourism and cultural sectors show a high degree of spatial linkage, placing them in a persistent “H–H” agglomeration area, signifying a high degree of inter-industry spatial linkage and a significant spillover effect on surrounding areas. Haibei, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefectures, and other western regions exhibit a relatively poor spatial correlation between tourism and cultural industries, and they have always been in an “L–L” agglomeration area. This indicates low-level development and synergy between tourism and cultural sectors in such regions. The driving effect of the surrounding areas is not significant, and these regions still require vigorous support for the development of integrated formats and strengthened cooperation with the surrounding provinces and cities. In 2011, areas such as Weinan City and Yulin City were characterized by an “L–L” agglomeration. However, by 2021, they had developed an “H–H” agglomeration, signifying that these areas significantly increased the spatial linkage between their tourism and cultural industries and their industrial synergy agglomeration degree, propelled by the development of surrounding industries. Hainan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture’s tourism and cultural industries displayed an “L–L” agglomeration in 2011, which had developed into an “H–L” agglomeration by 2021. This hints at a relatively high spatial correlation between the region’s tourism and cultural industries, with restricted spatial spillover to neighboring areas. Thus, the driving effect of the region on the surrounding provinces and cities is unclear, and interregional cooperation is difficult.

4.2. Analysis of Variables Impacting Tourism–Culture Collaborative Agglomeration Across the Yellow River Basin

4.2.1. Data Processing

An assessment of the spatiotemporal pattern evolution characteristics of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin indicates an early stage of development, with significant differences remaining in levels of integration across different regions. To further enhance tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration in this area and boost its development, systematical investigations of the influencing mechanisms must be accomplished based on the degree and spatial effects of their collaborative agglomeration development. Therefore, the SDM is deployed to examine the effects of selected variables on the collaborative agglomeration development of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries based on the indicator system of affecting factors (

Table 1).

Since the data utilized in the present work are all panel data, using the entropy weight method for the panel data to weigh each influencing factor is imperative before constructing the SDM. In this way, fluctuations in the data in terms of time and distance can be eliminated, and the subsequent analysis of the mechanism of action of the affecting factors can be achieved. When calculating the entropy weight method for panel data, each respective influencing factor should first be standardized year by year.

Positive influencing factors:

Negative influencing factors:

where

is normalized data,

stands for the original data of indicator

for region

in year

,

marks the lowest input value in the dataset of indicator

for year

, and

stands for the maximum value in the original data of indicator

for year

. Then, the proportion of indicators was determined:

where

stands for the proportion of indicator

in region

, while

and

stand for the total number of regions and time nodes, respectively. Subsequently, information entropy was calculated for each variable as follows:

where

is the total sample size. Finally, we calculated the weight of the indicators:

where

refers to the weight of indicator

, while

defines the number of indicators.

After obtaining the weights of various influencing factors, the present work uses the categories of factors related to the collaborative agglomeration of Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries in

Table 1 to conduct a weighted average calculation in six categories: industry resources, industry economy, human resources, industry policy, market demand, and industry innovation. The mathematical expression is

where

is the weighted average of class

influencing factors. After calculating the weighted averages of six types of influencing factors, namely industry resources, industry economy, human resources, industry policy, market demand, and industry innovation, taking these six types of influencing factors as explanatory variables and the degree of collaborative agglomeration of the cultural and tourism industries in the Yellow River Basin (tourism–culture CAD) as the explained variable, the present work constructs an SDM and analyzes the mechanisms of various influencing factors.

4.2.2. Testing the SDM

The Lagrange Multiplier (LM) test was initially utilized in this study to determine whether spatial lag and error effects were present in the dataset, ensuring the soundness of the SDM estimation. The test results are revealed in

Table 4.

According to

Table 4, the data on influencing variables for tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration in the basin passed the significance test of LM detection, signifying that the data has spatial errors and spatial lag effects. Then, the LR test, Wald test, and Hausman test were conducted to determine the random and fixed effects of the model, with the test results unveiled in

Table 5.

According to

Table 5, significance in the LR, Wald, and Hausman tests at the 1% level hints that employing an SDM with fixed effects provides the most robust framework for analyzing the data.

4.2.3. SDM Construction and Result Analysis

Based on the above analysis, referring to Equation (5) and with the help of Stata 17.0 software, an SDM with fixed effects is constructed in the present study to investigate the affecting factors for the collaborative agglomeration between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism industry and cultural industry. With respect to the choice of the SWM, it is considered that changes in the industrial structure of the basin’s tourism and cultural industries will be influenced by the industrial structure, human resources, and economic level of geographically adjacent regions. Therefore, in the construction of the SWM in the present work, the geographic distance matrix (

) stands for the degree of spatial correlation caused by the distance between two regions. The economic distance matrix (

) stands for the degree of economic connection between two regions. More similar economic development levels and geographical distances of regions hint at a greater impact coefficient assigned by the economic distance weight matrix.

Table 6 lists the SDM results.

The SDM estimation results (

Table 6) demonstrate a temporal lag coefficient of 0.851 (

p < 0.01), confirming that collaborative agglomeration in tourism and culture sectors tends to persist and strengthen over time. The spatial lag coefficient at 0.154 and significance at the 1% threshold indicates that regional gains in agglomeration contribute to similar developments in nearby regions. Accordingly, the collaborative agglomeration between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism industry and cultural industry exerts a spillover effect on different regions.

To further study the intrinsic mechanism of the factors influencing the collaborative agglomeration between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism industry and cultural industry and probe into the direct and indirect effects of each affecting factor, a partial differentiation treatment is conducted on each influencing factor according to Equation (6). The direct, indirect, and total effects of the affecting factors are examined from the perspectives of short- and long-term effects.

Table 7 presents the decomposition results.

The decomposition results in

Table 7 uncovered that industrial resources significantly and positively affect tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration in both immediate and extended terms. This sustained impact illustrates their key role in facilitating long-term tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration, pointing to the importance of targeted resource mining, optimization, and protection. Meanwhile, based on the research of Zhou et al. [

6], it is known that the coupling degree of industrial resources has the potential to produce an impact on tourism–culture coupling and coordination, which further verifies that industrial resource factors have a positive impact on tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration in the basin. The indirect effect of industrial resource factors is not considerable in either the short or long term, indicating that these factors exert influences on the tourism–culture CAD in the local region but only slightly affect adjacent regions, and a scale effect has not been formed. This is because tourism and cultural industry resources have strong embeddedness and geographical attributes that are difficult to replicate in other regions. As a result, tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration does not exert a remarkable impact on adjacent areas.

The industrial economy has positive direct, indirect, and overall effects on the synergy and agglomeration between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism industry and cultural industry in the short and long term, signifying that the factors of the industrial economy have long-term positive effects and a spatial spillover effect on the collaborative agglomeration development in these industries. This implies that tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the Yellow River Basin cannot progress effectively in the absence of industrial economic support. Therefore, only by assuring the healthy and sustained development of the industrial economy can these industries collaborate. Furthermore, the development of the industrial economy has spatial spillover effects; thus, industrial economic factors also exert influences on both the collaborative agglomeration and development of these industries in the areas adjacent to the basin.

The direct and overall contributions of human resource factors to tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the Yellow River Basin are also positive across the temporal scale, indicating that human resource factors have long-term positive effects on the collaborative agglomeration development of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries. This hints that sufficient labor can ensure the collaborative development of these industries. Weber’s research [

23] on industrial agglomeration also verifies that labor is pivotal factor in industrial agglomeration development. The human resources in the Yellow River Basin exhibit relatively low values of the direct effect and the total effect, signifying that this factor has limited the impetus for tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration development. This is attributed to the uneven distribution of human resources in the basin and significantly different human resource levels among regions, which, in turn, reduces the impact of this factor on the tourism–culture CAD in the basin. The indirect effect of human resource factors is negative in both the short and long terms, demonstrating that this factor only boosts tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in the local area and restricts tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in adjacent areas. Thus, when human resources are gathered in the same region, it boosts the development of industries that area, whereas adjacent regions are limited by a shortage of human resources, leading to uneven spatial development.

Industrial policy factors have positive direct, indirect, and overall effects on tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the Yellow River Basin across the temporal scale, indicating that industrial policy factors have a positive overall impact. The comparison of short- and long-term effects shows that industrial policies have the most significant promoting effect in the short term. However, as the policy release time increases, the facilitation of this factor on collaborative agglomeration gradually weakens. Therefore, to ensure tourism and cultural industries’ sustainable agglomeration and development in the Yellow River Basin, continuously adjusting industrial policies according to the actual situation is imperative. A comparison of direct and indirect effects shows that industrial policies yields a stronger impact on tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration development in the local area than that in adjacent areas, hinting that industrial policies exert a direct impact on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration development in the local area. After being affected by spillover effects, adjacent areas will also follow the industrial policies of the region and promote tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration development.

Market demand has positive long-term direct and overall effects on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration in the Yellow River Basin across temporal scales, supporting long-term integration within the basin. This indicates that market demand can boost tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration and development across the basin, with a direct impact on local tourism and cultural industries’ agglomeration and development. However, market demand factors exert a significant inhibitory effect on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in adjacent regions. This indicates that an increase in market demand for integrated tourism and cultural products in a region will continue to boost tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in neighboring areas. Therefore, various regions in the basin need to develop differently based on the characteristics of their local tourism and cultural industries to alleviate the inhibitory effect of market demand factors on tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration.

Industrial innovation factors have positive direct, indirect, and overall effects on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin in both the short and long terms, hinting that industrial innovation factors facilitate tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration development in this area. A comparison of the short- and long-term effects unveils that the long-term effect of industrial innovation factors on tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration development in the basin is higher than the short-term effect in that industrial innovation factors have a strong long-term impact on the two industries’ collaborative agglomeration development. This implies that the impact of this factor has a certain time lag and that the accumulation of innovative resources can boost the collaborative agglomeration development of both. The findings of Liu et al. [

27] confirm the positive impact of innovative resources on the degree of industrial coupling and coordination. Accordingly, accumulating and exploring industrial innovation resources in the long term and maximizing their roles in boosting tourism–culture collaborative development in this area are necessary. The comparison of direct and indirect effects reveals that industrial innovation factors exert a positive propelling impact on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration and development in both local and neighboring areas, indicating that this factor has spatial spillover effects. Each region can generate knowledge spillover effects through talent flow and technology exchange, thereby propelling tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration and development in neighboring areas and achieving scale effects.

4.2.4. Robust Test

Robustness is assessed by re-estimating the model with a modified SWM to verify the robustness of the results. Considering that measuring the simple spatial correlation across the Yellow River Basin by a single distance metric may lead to certain biases, the present work further constructs an SDM via an economic geographic nested SWM (

), which stands for the product of the elements in

and

. The estimation results of the SDM following supplant of the SWM are listed in

Table 8.

As unveiled in

Table 8, the SDM produces consistent and significant regression outcomes even after replacing the SWM, aligning with those obtained using both geographic and economic matrices, which verifies the stability of the model.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study integrates both spatial and temporal dimensions to investigate the collaborative clustering patterns of tourism and cultural sectors within the Yellow River Basin, based on panel data from 69 regional units (2011–2021). By employing spatial autocorrelation testing, we determined the spatiotemporal pattern evolution characteristics of tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration in the Yellow River Basin from the dual perspective of time and space, and then we used the SDM to determine the factors and mechanisms driving these changes. The primary findings are discussed below.

(1) From 2011 to 2021, a positive correlation was noted in the overall spatial autocorrelation degree of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries. Moreover, it showed a changing “rising–falling–rising” trend over time. Spatially, the degree of GSA of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the basin gradually increased, and the distribution characteristics are “higher in the central and eastern regions but lower in the western regions.” Temporally, from 2011 to 2014, yearly increased spatial correlations were noted between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries owing to rapid socio-economic development, and the level of their collaborative agglomeration was also improved to some extent. From 2015 to 2017, affected by the industrial structure transformation, a slight drop was noted in the GSA index of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries, but a positive correlation was still noted between them. From 2018 to 2021, another elevation was noted in the degree of GSA of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries owing to the establishment of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in China, influenced by national policies. Spatially, a gradual upward trend was noted in the GSA of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin regions. Influenced by factors like the regional economic level and infrastructure, the degree of GSA of the tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the basin was “higher in the central and eastern regions versus in the western regions”.

(2) From 2011 to 2021, the degree of LSA of the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries remained at a relatively low level, and significant differences were noted in the degree of LSA among different regions. Temporally, with the support of industrial policies plus socio-economic factors, the tourism and cultural industries in various Yellow River Basin regions have achieved certain development, and the degree of industrial correlation gradually increased. The degree of LSA between the Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries is therefore characterized by a decreasing trend in the quantity of “L–L” agglomeration areas and an increasing trend in the quantity of “H–H” agglomeration areas. Meanwhile, the change in the quantity of “H–L” and “L–H” agglomeration areas is relatively minor. Spatially, significant differences are noted in the degree of LSA between the tourism and cultural industries across the basin. A relatively high LSA degree of the tourism and cultural industries, along with remarkable industrial linkage effects between regions, is noted in the basin’s central and eastern regions. However, in the basin’s western region, affected by the economic level and the construction level of infrastructure such as transportation, a relatively low LSA degree of the tourism and cultural industries is noted, and the inter-regional industrial linkage effect still needs to be further improved.

(3) Factors influencing tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration across the Yellow River Basin have temporal superposition and spatial radiation-driving effects. Among them, industrial economic factors, industrial policy factors, and industrial innovation factors exert a long-term impact on this agglomeration and produce spatial spillover effects. This implies that the industrial economy, policies, and innovations propel tourism–culture collaborative development across the basin and its neighboring areas. The direct and total effects of industrial resource factors on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration development in the Yellow River Basin are positive, whereas their indirect effects are of no significance in either the short or long term. This signifies that this factor only affects the tourism–culture CAD in the local area and exerts no significant impact on adjacent areas. Human resources and market demand factors exert positive direct and total effects on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in the Yellow River Basin, whereas their indirect effects are negative. This indicates that these two factors have a positive impact on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in the Yellow River Basin but exert an inhibitory impact on tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in neighboring areas.

Several recommendations are proposed based on the above conclusions. First, the characteristics of tourism–culture collaborative agglomeration within the Yellow River Basin need to be fully understood while maintaining the advantages of this agglomeration in the central and eastern regions and continuously developing integrated products of tourism and cultural industries. The Yellow River Basin’s western region should fully tap into its own tourism and cultural resources, increase the characteristics of artistic and touristic commodities, and strengthen industrial cooperation.

Second, based on the goal of ensuring their own developmental advantages, the Yellow River Basin’s central and eastern regions must break through administrative regional restrictions through talent and technology exchanges and achieve spatial radiation and driving effects. By exploring its own tourism and cultural industries’ resource characteristics, the Yellow River Basin’s western region actively seeks cross-regional cooperation and utilizes the industrial linkage effect between regions to alleviate its own industrial development pressure. Simultaneously, the government should increase its efforts to support tourism and cultural industry development in the western Yellow River Basin, strengthen infrastructure construction in the western region, and solve the development difficulties in the western Yellow River Basin’s tourism and cultural industries.

Third, the government should not only strengthen the positive driving role of industrial economy, policies, and industrial innovation resources but also pay attention to cross-regional cooperation and collaborative participation in the development of tourism and cultural industries, enhancing the spatial spillover effects of factors such as economy, policies, and innovation resources. Governments in all Yellow River Basin regions should not only conserve existing tourism and cultural industry resources but also continuously optimize, enrich, and explore tourism and cultural industry resources, maintain the uniqueness of regional industrial resources, and enhance the role of industrial resources in boosting local tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development. The government should establish a regional collaborative development mechanism and interest compensation mechanism from the aspects of human resources and market demand so as to reduce the “siphon effect” and achieve tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development among disparate regions in the basin.

6. Limitations and Prospects

The present work is based on the dual perspective of “time–space” in the process of industrial collaborative agglomeration and demonstrates the spatiotemporal evolution characteristics of tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration in the Yellow River Basin from both theoretical and empirical perspectives. The present work, identified the affecting factors and internal mechanisms affecting the development of the two collaborative agglomerations and proposed countermeasures and suggestions to boost tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration development in the basin. The Yellow River Basin, a crucial region for Chinese tourism and cultural industry development, has undergone forward-looking and comparable research on its spatial and temporal patterns and the factors influencing the synergy between the tourism and cultural industries. The countermeasures and suggestions proposed in the present work to boost tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in the Yellow River Basin possess reference value for tourism and cultural industry development in similar regions worldwide.

Nonetheless, the present work still possesses some shortcomings. First, the present work concentrates on the issue of tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration development. Nevertheless, the collaborative agglomeration of industries is a multifarious concept. The affecting factors for this agglomeration are diverse, encompassing industry resources, policies, and the economic environment. The indicator system of affecting factors for tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative agglomeration in the Yellow River constructed in the present work is based on the existing research results and the statistical yearbooks published by the National Bureau of Statistics. Moreover, most of the research data are sourced from official statistics, which have a certain degree of lag. Therefore, on-the-spot investigations are needed for further improvement. Second, owing to research data availability, the present work examined the affecting factors and underlying mechanisms of tourism and cultural industries’ synergistic agglomeration in the Yellow River Basin by carrying out weighted averaging of the research data of each affecting factor, thus lacking a detailed analysis for disparate regions of the basin.

Future research may concentrate on two principal themes. The first research avenue could involve a more granular analysis of how regional disparities influence the relationship between key factors and tourism–culture agglomeration. Moreover, field investigations may help increase the real-time reliability of the associated data indicators. Second, an investigation can be performed in response to the current situation and characteristics of tourism and cultural industries’ collaborative development in Yellow River Basin regions to explore the degree of influence and the driving mechanisms of various influencing factors.