Reintegrating Marginalized Rural Heritage: The Adaptive Potential of Barn Districts in Central Europe’s Cultural Landscapes

Abstract

1. Introduction

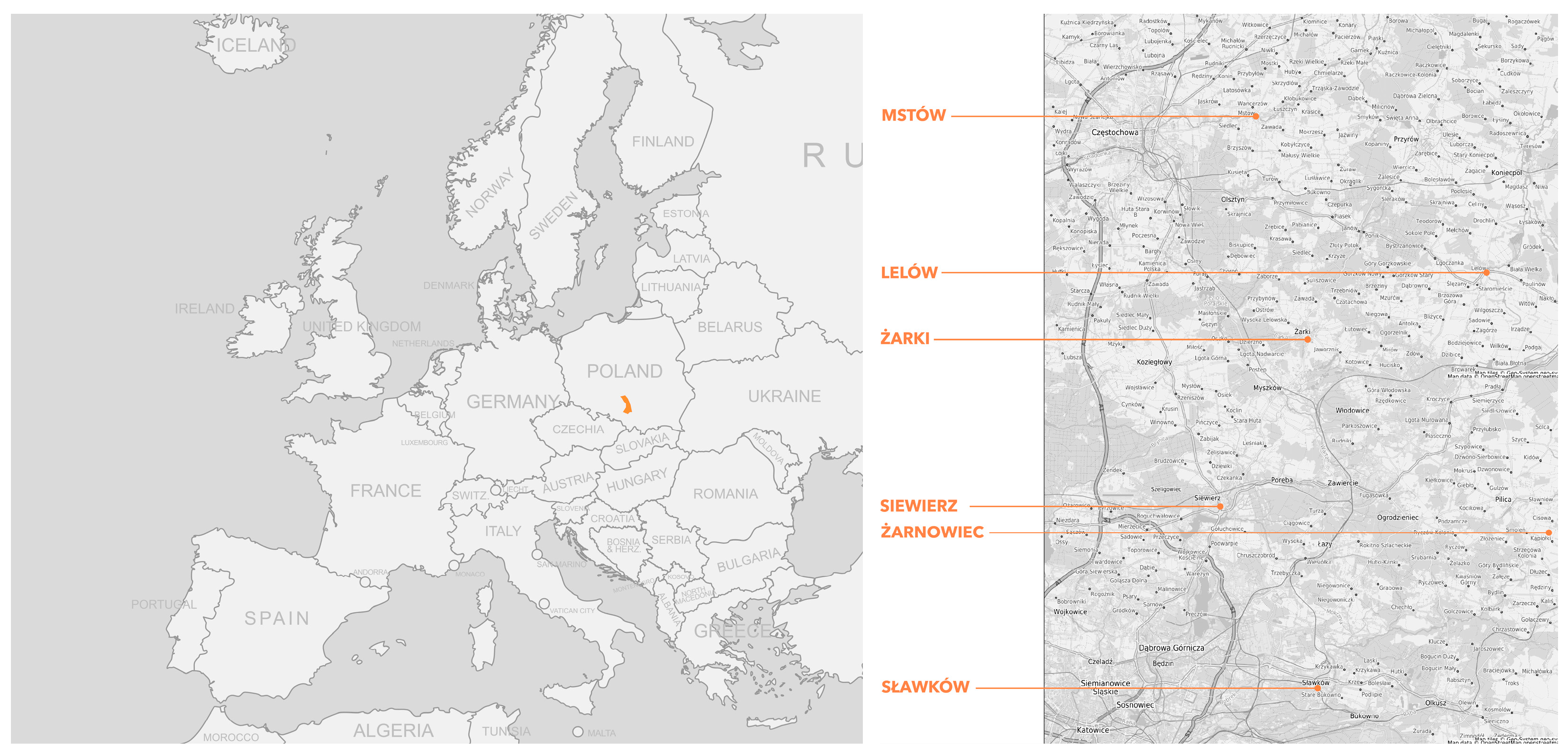

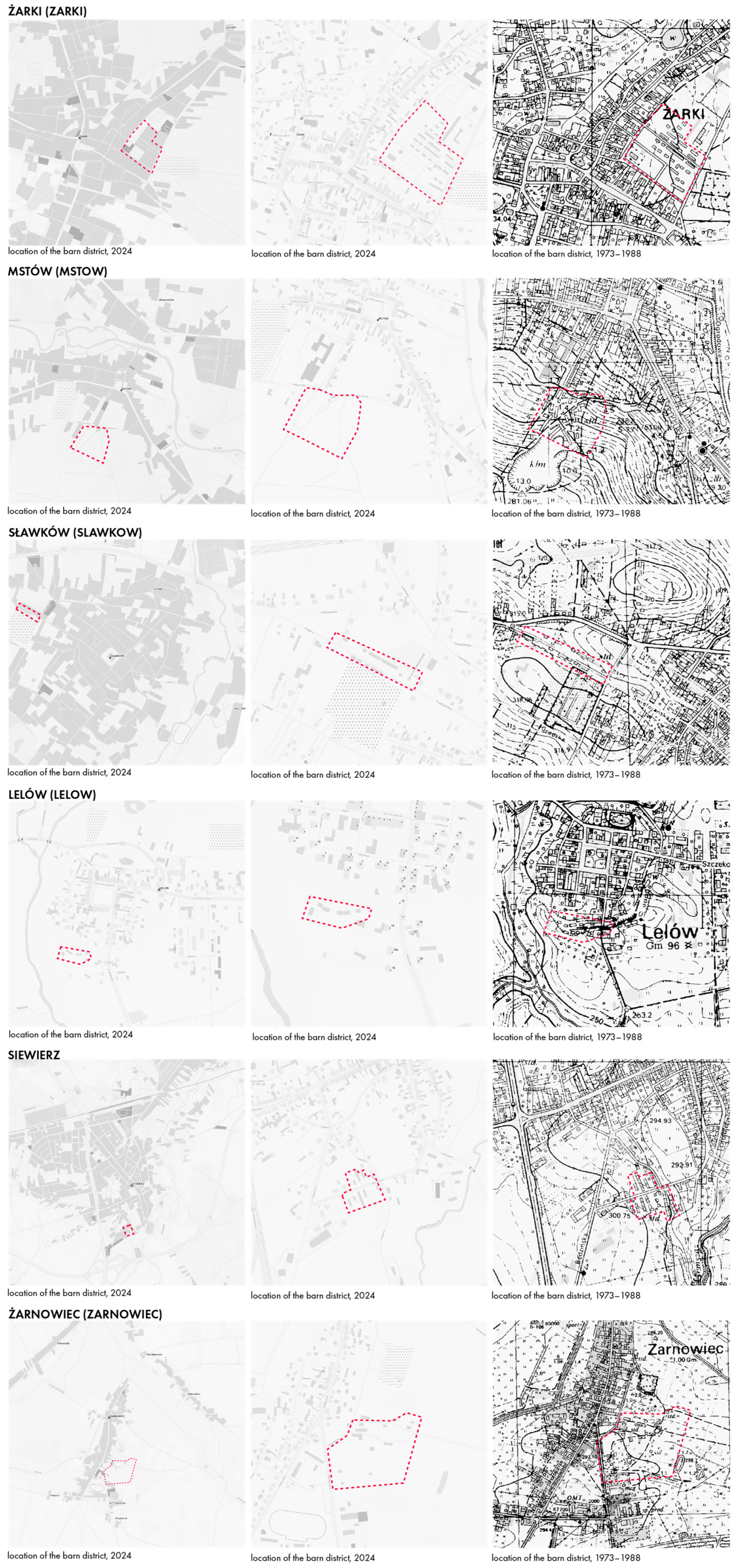

1.1. Research Aim and Scope

1.2. Historical and Urban Context of Barn Districts

1.3. Research Hypotheses

1.4. Research Context and Relevance for Urban Practice

1.5. Literature Review and Research Gap

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature and Historical Source Review

2.2. Field Studies and Morphological Analysis

2.3. Interviews with Residents and Experts

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Selected Barn Districts

3.1.1. Żarki

3.1.2. Mstów

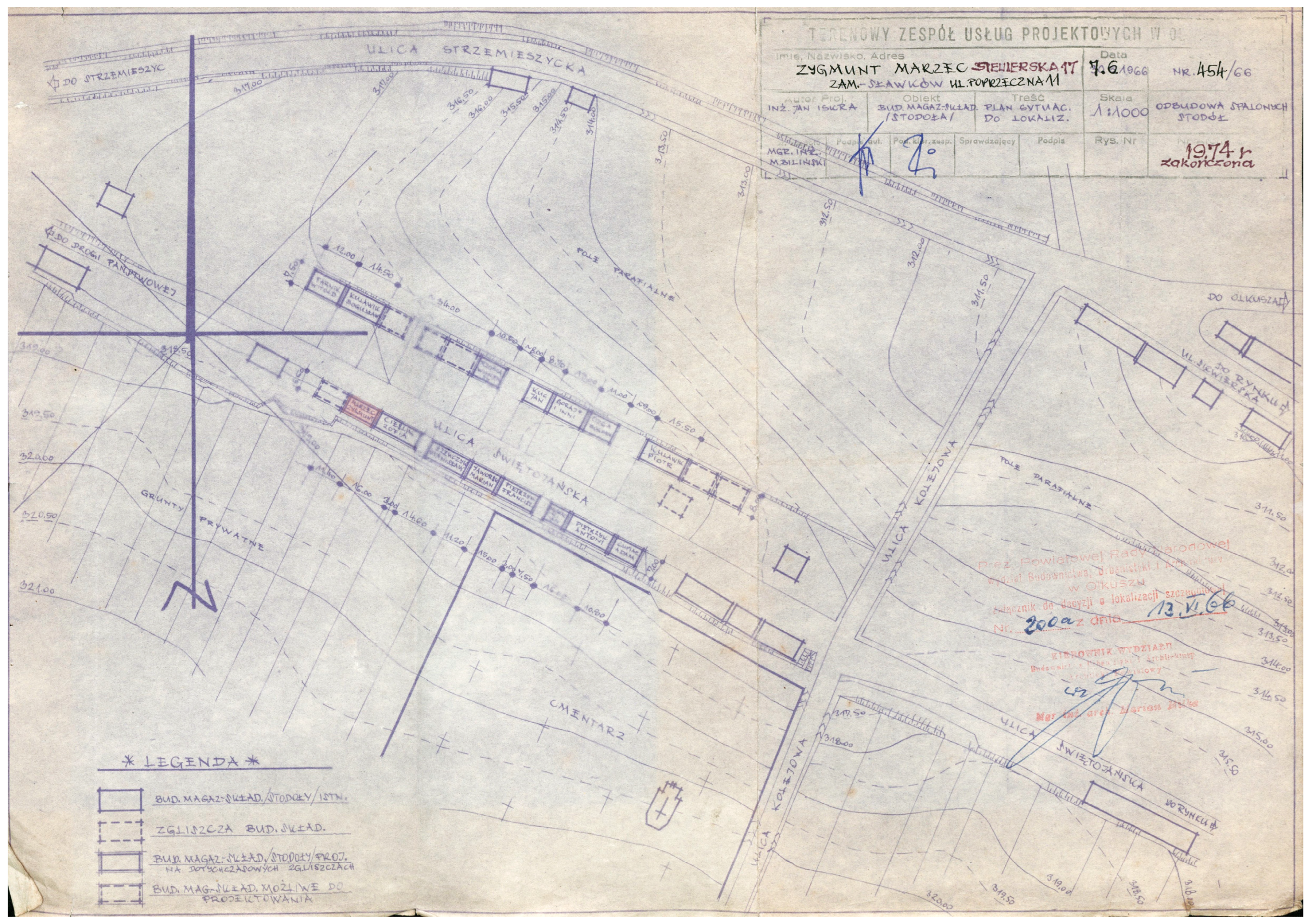

3.1.3. Sławków

3.1.4. Lelów

3.1.5. Siewierz

3.1.6. Żarnowiec

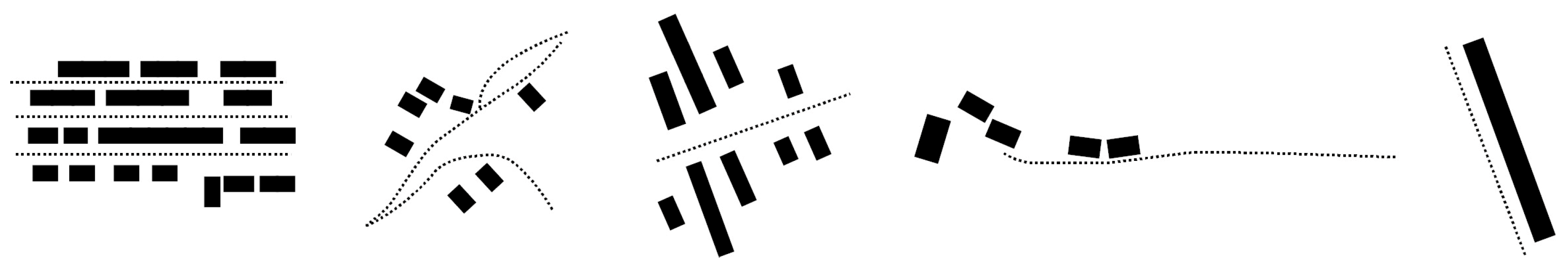

3.2. Morphological Transformations and Urban Layout of Barn Districts

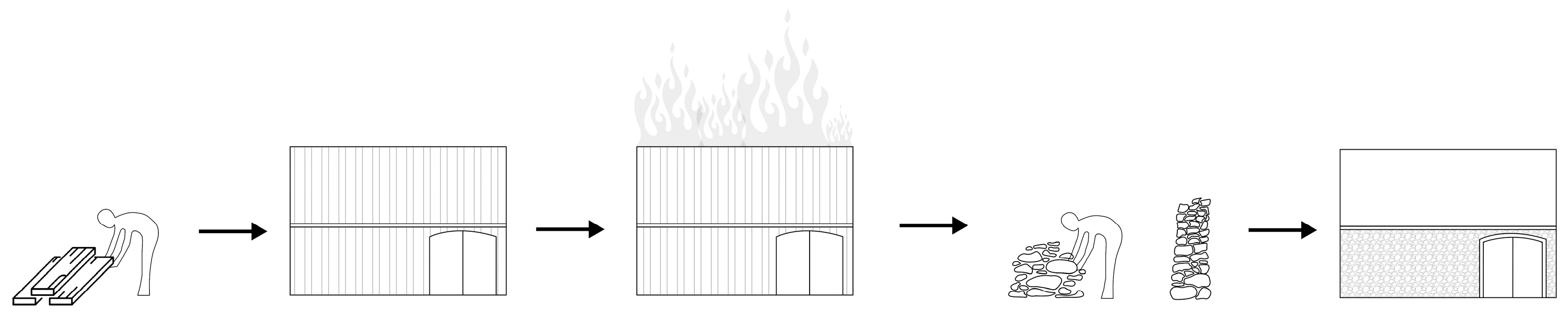

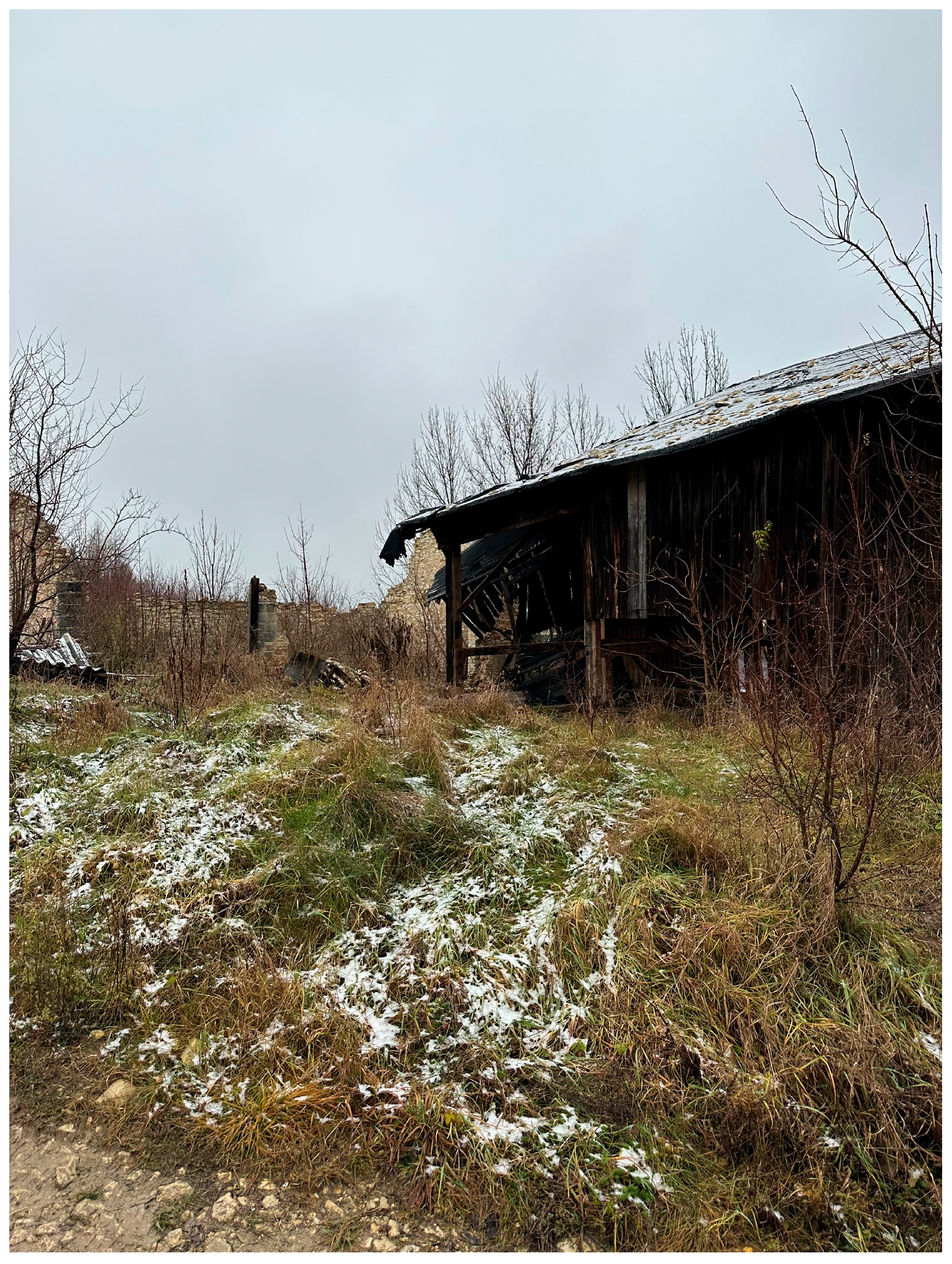

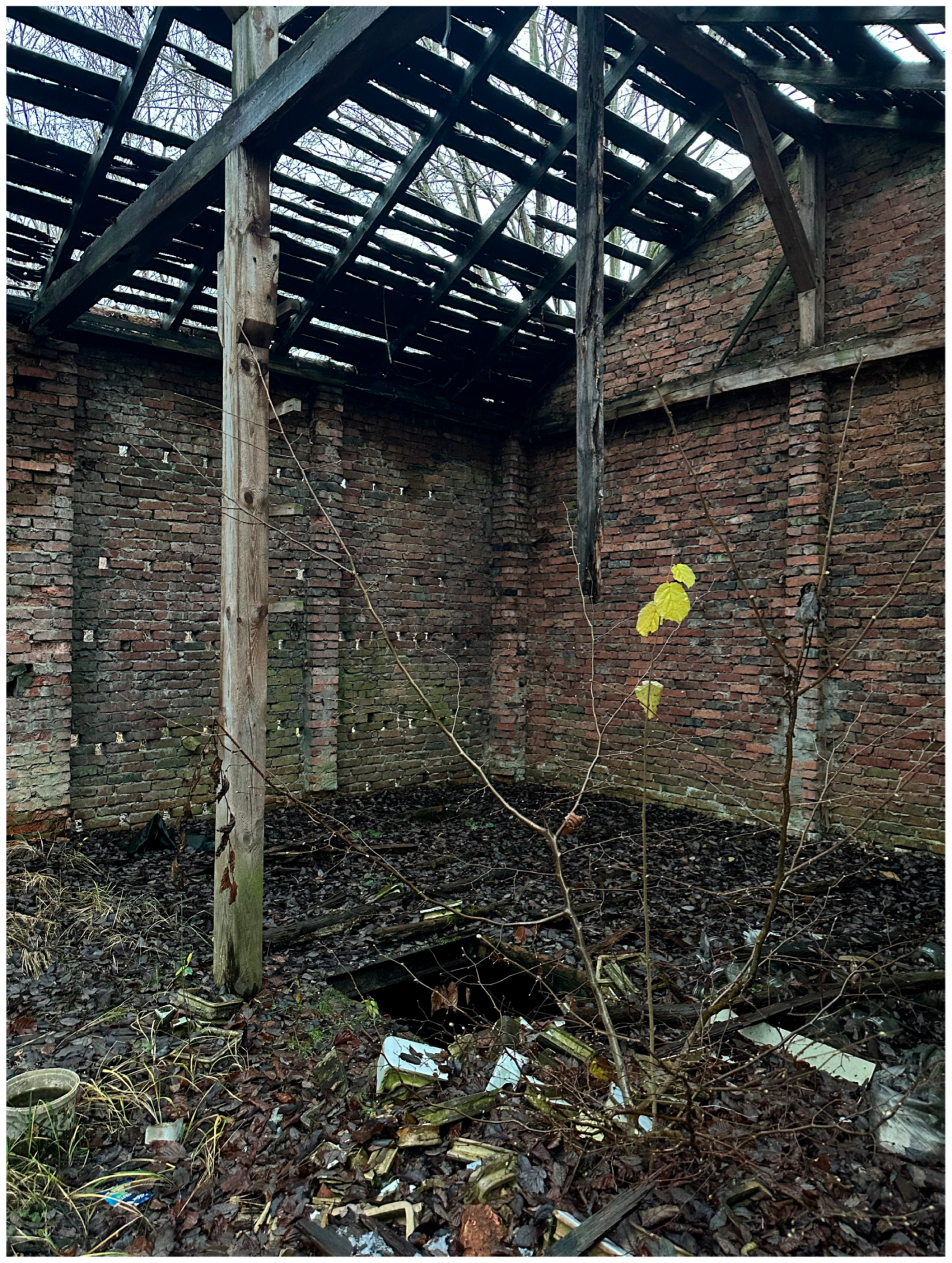

3.3. Architectural Characteristics and Technical Condition

3.4. Barn Districts in Social Perception and Their Role in Cultural Heritage

4. Discussion

4.1. Heritage Values and Landscape Relevance

- Scheunenviertel in Germany (e.g., Kremmen, Friedland, Steinhude, Schlüsselburg) developed from the 17th century onward, often in response to urban fire-safety regulations that prohibited barns within dense town cores. These barn quarters were typically located just outside city walls and arranged linearly for functional and safety reasons. While some examples—most notably in Kremmen—have been preserved and repurposed as cultural tourism assets, others face degradation or ad hoc transformation.Relevant studies such as Busse [6] and Kleine-Limberg [7] provide valuable documentation of their morphology, typology, and conservation status, but focus primarily on architectural classification and heritage protection. Nevertheless, these works do not adopt landscape-scale or participatory methodologies, nor do they address socio-spatial dynamics in depth.

- Cistercian granges, present in France and Central Europe (12th–15th centuries), were institutionalized monastic farm complexes typically located at a distance from settlements. Although spatially coherent and functionally integrated, these ensembles reflected centralized ecclesiastical land control rather than communal rural practice [62].

4.2. Adaptive Reuse Potential: Typologies, Challenges, and Comparative Insights

- Linear configurations (e.g., Żarki, Siewierz): These ensembles are aligned parallel to roads or plot boundaries, forming cohesive, row-like patterns. Their regularity, accessibility, and proximity to central urban infrastructure offer high potential for adaptive reuse, including commercial or service functions.

- Compact clusters (e.g., Sławków): Often located within or adjacent to historical town centers, these barn districts demonstrate spatial proximity to cultural landmarks and public infrastructure. However, their smaller scale, fragmentation, and limited separation from surrounding buildings can constrain functional transformation.

- Dispersed layouts (e.g., Mstów, Lelów, Żarnowiec): Shaped by local topography, parcel fragmentation, and less formal spatial logic, these districts typically occupy peripheral, less accessible sites. Their current condition varies from partial preservation to near disappearance, which presents challenges for reintegration into contemporary townscapes but also opportunities for low-intervention, landscape-sensitive reuse.

- Physical degradation, particularly in timber and limestone structures, limits immediate adaptation without stabilization.

- Legal ambiguity, including unresolved ownership or zoning designations, complicates planning and investment.

- Poor accessibility and infrastructure, especially in hilltop or outlying districts, restricts usage for daily or intensive functions.

- Low investor interest, due to the sites’ perceived obsolescence and uncertain profitability, hinders large-scale revitalization efforts.

- Open-air markets;

- Artisanal workshops;

- Cultural or educational venues;

- Storage for eco-products or tools supporting local circular economies.

4.3. Two Contrasting Cases: Żarki and Mstów

4.4. Socio-Economic and Demographic Conditions

4.5. Toward Integrated Models of Rural Heritage Revitalization

- Functional Continuity Models (e.g., Żarki, Sławków): Prioritize adaptive reuse based on existing or historic uses (e.g., markets, craft production), with interventions focusing on repair, modernization, and improved accessibility.

- Interpretive Landscape Models (e.g., Mstów): Emphasize educational, symbolic, and visual reuse, including trails, temporary installations, or heritage storytelling linked to cultural tourism and school programs.

- Hybrid Strategies: Applicable in sites such as Siewierz or Żarnowiec, where spatial integrity exists but economic capacity is limited. Here, phasing and mixed-use scenarios may support gradual transformation through modest investment and community involvement.

- Technical assessment—evaluation of structural safety, material degradation, and fire protection needs to determine feasible levels of reuse.

- Legal and planning integration—securing zoning provisions and resolving ownership issues through local spatial development plans.

- Scenario-based design—preparation of alternative design concepts (e.g., seasonal use, modular adaptation), tailored to site-specific conditions.

- Community engagement and co-design—participatory planning sessions, workshops, and educational initiatives aimed at fostering local ownership and youth involvement.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Trawińska, M. Z Badań Nad Budownictwem Wiejskim w Rejonie Częstochowskim [Research on Rural Architecture in the Częstochowa Region]. Rocz. Muz. W Częstochowie 1966, 2, 79–110. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wancel, A. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland); Wróblewski, S. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communication, 2025.

- Conzen, M.R.G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis; Institute of British Geographers Publication: London, UK, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Muratori, S. Studi per una Operante Storia Urbana di Venezia; Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato: Rome, Italy, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Caniggia, G.; Maffei, G.L. Interpreting Basic Buildings: Architectural Composition and Building Typology; Alinea Editrice: Florence, Italy, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, A. Das historische Scheunenviertel Kremmen. Aktion Denkmal des Monats; Arbeitsgemeinschaft Historische Stadtkerne Brandenburg: Potsdam, Germany, 2014; Available online: https://ag-historische-stadtkerne.de/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/15-06-DdM_Kremmen.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025). (In German)

- Kleine-Limberg, W. Scheunenviertel und mehr: Sonderquartiere in historischen Siedlungen in Niedersachsen; Institut Mensch und Region/Niedersächsisches Ministerium: Hannover, Germany, 2012; Available online: https://mensch-und-region.de/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/nsgb-1_2012-scheunenviertel-und-mehr.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025). (In German)

- Dragan, A.; Creţan, R.; Jucu, I.S.; Oancea, O.A. Rural Landscapes as Cultural Heritage and Identity along a Romanian River. Heritage 2024, 7, 4354–4373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagiotopoulos, D.; Wallenwein, F.; Mildenberger, G.; Schimpf, G.-C. A Dialogue between the Humanities and Social Sciences: Cultural Landscapes and Their Transformative Potential for Social Innovation. Heritage 2023, 6, 7674–7705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, G.; Sarlöv Herlin, I.; Swanwick, C. (Eds.) The Routledge Handbook of Landscape Character Assessment; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, K.; Lennon, J. Cultural landscapes: A bridge between culture and nature? Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2011, 17, 537–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira Roders, A.; van Oers, R. Bridging cultural heritage and sustainable development. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2011, 1, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniewicz, M. Dzieje Żarek: Zarys Powstania i Rozwoju Miasta na Przestrzeni Sześciu Wieków; [The Past of Żarki: Outline of the Origin and Development of the Town Over Six Centuries]; Towarzystwo Miłośników Żarek: Żarki, Poland, 1982; 64p. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Laberschek, J. Średniowieczne Dzieje Nadwarciańskiego Mstowa; Wydawnictwo Towarzystwa Naukowego „Societas Vistulana”: Kraków, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kubicki, A. Z Przeszłości Mstowa: Notatki Kronikarskie od Średniowiecza do 1939 Roku; [The Past of Mstów: Chronicle Notes from the Middle Ages to 1939]; Drukarnia Usługowa “Gryf”: Częstochowa, Poland, 2011. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ławrynowicz, O.; Krupa-Ławrynowicz, A.; Gadowska, I.; Nita, M.; Majorek, M.; Cieśliczka, A.; Majewska, A. Miejsca Pamięci i Zapomnienia. Studium Interdyscyplinarne na Jurze Krakowsko-Częstochowskiej. Tom 5. Gmina Lelów; [Sites of memory and forgetting. An interdisciplinary study in the Kraków-Częstochowa Jura. Vol. 5. Lelów Commune]; University of Łódź. 2019. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/11089/43070 (accessed on 15 May 2025). (In Polish).

- Dyduch-Falniowska, A.; Makomaska-Juchiewicz, M.; Kaźmierczakowa, R.; Perzanowska, J.; Zając, K. Integration of Information on the Kraków-Czestochowa Jura for Conservation Purposes: Application of CORINE Methodology. In National Parks and Protected Areas; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; pp. 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupa-Ławrynowicz, A. Zmiany i napięcia w krajobrazie wsi jurajskiej. Na marginesie badań w Mstowie [Changes and tensions in the landscape of a Jura village. On the margins of research in Mstów]. Zesz. Wiej. 2016, 22, 153–167. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myga-Piątek, U.; Żemła-Siesicka, A. How Has the Landscape Changed? Landscape Transformation Analysis of Ogrodzieniec-Podzamcze (Poland) Using Landgraphy and Landscape Stratigraphy Methods. Landsc. Online 2023, 98, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figlus, T. Process of Incorporation and Morphological Transformations of Rural Settlement Patterns in the Context of Urban Development: The Case Study of Łódź. Quaest. Geogr. 2020, 39, 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figlus, T. The past and present of historical morphology of rural and urban forms in Poland. Stud. Geohistorica 2018, 6, 149–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, A. Wskazanie potrzeb rewitalizacyjnych oraz analiza przeprowadzonych dotychczas działań mających na celu rewitalizację wsi Mstów [Identification of revitalization needs and analysis of conducted revitalization activities in Mstów village]. Stud. Obsz. Wiej. 2018, 49, 7–24. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, A. Zabytkowa dzielnica stodół w Mstowie. Strategia ochrony i projekt zagospodarowania [The historic barn quarter in Mstów. A protection strategy and a development plan]. In Miejsca Pamięci i Miejsca Zapomnienia w Krajobrazach Kulturowych Jury Krakowsko Częstochowskiej; Ławrynowicz, O., Krupa Ławrynowicz, A., Eds.; Instytut Archeologii, Uniwersytet Łódzki: Łódź, Poland, 2019; pp. 147–162. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Wolski, O.; Różycki, P. Management of tourist values on the example of the Mstów commune. Geotourism/Geoturystyka 2012, 3–4, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkham, P.J.; Ashworth, G.J. A Heritage for Europe: The Need, the Task, the Contribution. In Building a New Heritage: Tourism, Culture and Identity in the New Europe; Ashworth, G.J., Larkham, P.J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 1994; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Larkham, P.J.; Adams, D. The Character of Urban Form in Historic Urban Cores: Reconstructing the Morphology of Pre-Modern Towns. Urban Morphol. 2019, 23, 125–139. [Google Scholar][Green Version]

- Wróblewski, S. Kolor i faktura w budownictwie wsi regionu Jury Krakowsko-Częstochowskiej [Color and texture in the architecture of villages in the Kraków-Częstochowa Jura region]. Architectus 2000, 1, 137–141. Available online: https://dbc.wroc.pl/publication/59048 (accessed on 15 May 2025). (In Polish).[Green Version]

- Szymański, S. Budownictwo z wapienia jurajskiego w Częstochowie [Architecture in Jurassic limestone in Częstochowa]. In Rocznik Muzeum w Częstochowie; Błaszczyk, W., Ed.; Muzeum w Częstochowie: Częstochowa, Poland, 1966; pp. 111–142. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Nita, J.; Plit, J.; Nita, M. Surowce skalne jako materiał budowlany—Analiza zachowanych wyróżników regionalnych [Rock raw materials as building material—Analysis of preserved regional features]. Pr. Kom. Kraj. Kult. 2018, 32, 65–78. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzeł, T. Z badań nad budownictwem ludowym Kotliny Rabczańskiej [Research on folk architecture in the Rabka Valley]. Pr. Etnogr. 2017, 45, 71–87. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Greenop, K. From ‘neo-vernacular’ to ‘semi-vernacular’: Reinterpreting vernacular architecture in China’s urban redevelopment. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2019, 25, 1128–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevoets, B.; Sowińska-Heim, J. Community initiatives as a catalyst for regeneration of heritage sites: Vernacular transformation and its influence on the formal adaptive reuse practice. Cities 2018, 78, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, P.; Fernández, M. Rural development and heritage commons management in Asturias, Spain: The Ecomuseum of Santo Adriano. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2013, 19, 660–679. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10261/126379 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ordóñez-Castañón, D.; Cunha Ferreira, T. Toward the Adaptive Reuse of Vernacular Architecture: Practices from the School of Porto. Heritage 2024, 7, 1826–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L. Adaptive Reuse in Architecture: A Typological Index; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Prieto, V. Vernacular architecture and their setting vulnerability. In Proceedings of the 15th ICOMOS General Assembly and International Symposium (ICOMOS 2005), Xi’an, China, 17–21 October 2005; pp. 2–6. Available online: http://openarchive.icomos.org/342/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Loisel, P.; Maurel, P.-Y.; Conversy, B. Farm Buildings and Agri-Food Transitions in Southern France: Mapping Dynamics Using a Stakeholder-Based Diagnosis. Geogr. Sustain. 2023, 5, 108–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergevoet, T.; Korthals Altes, W.K. Re-Using Vacant Farm Buildings for Commercial Purposes: Two Cases in the Netherlands. Land Use Policy 2023, 132, 106713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilmez, Z.D.; Hersek, N. Conservation and Restoration Works in England: Conversion of Barns. Gazi Univ. J. Sci. Part B Art. Humanit. Des. Plan. 2024, 12, 97–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maté González, M.Á.; Herrero-Tejedor, T.R.; Pérez-Martín, E.; Villanueva, P. Documentation and Virtualisation of Vernacular Cultural Heritage: The Case of Underground Wine Cellars in Atauta (Soria). Heritage 2023, 6, 5130–5150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picuno, P. Farm Buildings as Drivers of the Rural Environment. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 693876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleszyński, J. Jurajska Kraina. Przewodnik Turystyczny; [Jurassic Land. Tourist Guide]; Związek Gmin Jurajskich: Katowice–Ogrodzieniec, Poland, 2023; 96p. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Ptaszek, M. (Ed.) Jurajskie Przygody. Turystyka Aktywna: Ludzie, Pasje, Historie [Jurassic Adventures. Active Tourism: People, Passions, Stories]; Związek Gmin Jurajskich: Zawiercie, Poland; 52p, 2021. Available online: https://www.polskiemarkiturystyczne.gov.pl/uploaded_files/eve_1649838505_jurajskie-przygody-2021-kompresja.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025). (In Polish)

- Jakubczak, A. Mstów w czasach najnowszych [Mstów in Recent Times]. In Mstów. Miasto—Klasztor—Parafia. Na Przestrzeni Wieków; Łatak, K., Ed.; Wydawnictwo LTW: Łomianki, Poland, 2013; pp. 9–15. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sroczyńska, J. Enhancing the Attractiveness of Architectural Monuments as Tourist Attractions: Medieval Castle Ruins in the Kraków-Częstochowa Jura. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 471, 082062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwicka, S.; Milecka, M. The Use of Selected Landscape Metrics to Evaluate the Transformation of the Rural Landscape—A Case Study of the Puchaczów Commune. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koreleski, K. An Outline of the Evolution of Rural Cultural Landscapes in Poland. Rev. Română De Geogr. și Geol. 2007, 2, 23–28. Available online: https://rrrs.reviste.ubbcluj.ro/site/arhive/Artpdf/v3n22007/RRRS032200703.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Whitehand, J.W.R.; Gu, K. Urban Morphology and Conservation Planning: The Case of Tainan. J. Urban Des. 2006, 11, 217–236. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, V. Urban Morphology: An Introduction to the Study of the Physical Form of Cities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piras, F.; Pan, Y.; Santoro, A.; Fiore, B.; Min, Q.; Guo, X.; Agnoletti, M. Agro-Silvo-Pastoral Heritage Conservation and Valorization—A Comparative Analysis of the Chinese Nationally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems and of the Italian Register of Historical Rural Landscapes. Land 2024, 13, 988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevoets, B.; Van Cleempoel, K. Adaptive Reuse as a Strategy Towards Conservation of Cultural Heritage: A Literature Review. In Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XII; WIT Press: Southampton, UK, 2011; pp. 155–164. [Google Scholar]

- Wancel, A. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communications with local residents of Żarki (various ages and occupations), conducted during fieldwork interviews, 2025.

- Wancel, A.; (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communication with municipal representatives in Siewierz, 2025.

- Wancel, A. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communication with representatives of institutions in Mstów, 2025.

- Waterton, E.; Smith, L. The Recognition and Misrecognition of Community Heritage. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2010, 16, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wancel, A. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland); Mszyca, W. (Independent heritage researcher and local cultural activist, Żarki, Poland). Personal communication, 2025.

- Wancel, A. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland); Kaznodziej, D. (Cultural and Ecological Education Center, Municipal Cultural Center, Sławków, Poland). Personal communication, 2025.

- Komarzyńska-Świeściak, E. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland); Kirschke, P. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communication, 2025.

- Komarzyńska-Świeściak, E. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland); Belof, M. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communication, 2025.

- Komarzyńska-Świeściak, E. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland); Szumilas, A. (Faculty of Architecture, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland). Personal communication, 2025.

- Guilaine, J. Granges cisterciennes et aménagement rural au Moyen Âge. In Paysages Monastiques; CNRS Éditions: Paris, France, 2013; Available online: https://books.openedition.org/editionscnrs/14838 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Rogers, J. Tithe Barns of Britain. Peregrinations 2021, 7, 312–327. Available online: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol7/iss3/16 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Thoen, E. Tithe Barns in England: Symbols of Power and Agricultural Control. In Medieval Rural Settlement in Britain and Ireland; Le Patourel, H.E.J., Smith, J.T., Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (The Venice Charter). 1964. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Charter-of-Venice_1964.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity. 1994. Available online: https://landscapes.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/1994-NARA-document-on-authenticity-International-Council-on-Monuments-and-Sites-1.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- ICOMOS. Charter for the Conservation of Historic Towns and Urban Areas (Washington Charter). 1987. Available online: https://civvih.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Charter-of-Washington_10_1987.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- Termorshuizen, J.W.; Opdam, P. Landscape services as a bridge between landscape ecology and sustainable development. Landsc. Ecol. 2009, 24, 1037–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroli, B.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Cornish, P. Landscape—what’s in it? Trends in European landscape research and priority themes for future research. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 1447–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Landscape Sustainability Science: Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being in Changing Landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2013, 28, 999–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdam, P.; Steingröver, E.; van Rooij, S. Ecological Networks: A Spatial Concept for Multi-Actor Planning of Sustainable Landscapes. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 75, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa. Żarki—Zespół Stodół, ul. Piaski [Barn District Heritage Card]. 2024. Available online: https://zabytek.pl/pl/obiekty/zespol-48-stodol-869263 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Wancel, A. Stodoły 2.0—Reinterpretacja Zabytkowych Założeń Urbanistycznych Jury Krakowsko-Częstochowskiej na Przykładzie Dzielnicy Stodół w Żarkach [Barn 2.0—Reinterpretation of Historical Urban Layouts in the Kraków-Częstochowa Jura Based on the Barn District in Żarki]. Master’s Thesis, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland, 2024. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Borowska-Antoniewicz, J. Program Opieki Nad Zabytkami Gminy Mstów; Załącznik nr 1 do uchwały Rady Gminy Mstów nr XXXVII/249/2013 z Dnia 14 Września 2013 r, Mstów, Częstochowa; Municipal Council of Mstów: Częstochowa, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa. Mstów—Zespół Stodół [Barn District Heritage Card]. 2024. Available online: https://zabytek.pl/pl/obiekty/zespol-stodol-864070 (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Nowicka, A. Strategia Ochrony i Rozwoju Zabytkowej Dzielnicy Stodół we Mstowie [Strategy for the Protection and Development of the Historic Barn District in Mstów]. Master’s Thesis, Wrocław University of Science and Technology, Wrocław, Poland, 2015. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. New European Bauhaus. Available online: https://new-european-bauhaus.europa.eu/ (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Council of Europe. European Landscape Convention (Florence Convention). 2000. Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/landscape (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- ICOMOS. The Valletta Principles for the Safeguarding and Management of Historic Cities, Towns and Urban Areas. 2011. Available online: https://www.icomos.org/en/resources/charters-and-texts/404-icomos-charter-for-the-conservation-of-historic-towns-and-urban-areas-valletta-principles (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Stadt Kremmen. Scheunenviertel Kremmen. Available online: http://www.scheunenviertel-kremmen.com/verzeichnis/objekt.php?mandat=46491 (accessed on 8 July 2025).

| Location | Urban Layout | Graphic Scheme | Number of Preserved Buildings | Current Use | Proximity to Central Area | Transport Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lelów | Irregular layout |  | A few wooden barns; severely degraded; layout largely illegible | Presumed to be abandoned | Outskirts of village | Limited; barns accessed via overgrown, unpaved side road |

| Mstów | Irregular layout |  | Remains of single walls and foundations; layout lost | Abandoned structures | Outskirts of village | Limited; barns situated on a hill, accessed via unpaved rural path |

| Siewierz | Regular layout |  | About a dozen buildings without roofs; preserved linear arrangement | Abandoned structures | Town outskirts | Accessible by car; barns located along a paved road |

| Sławków | Regular layout |  | About a dozen buildings; dispersed and modified ensemble | Abandoned structures | Town outskirts | Accessible by car; barns located along a paved road |

| Żarki | Regular layout |  | Approx. 42 structures; well-preserved ensemble | Partially abandoned; some reused as warehouses or for market trade | Close to town center | Easily accessible by car; barns located along a main road |

| Żarnowiec | Irregular layout | No confirmed data | Only 2 wooden barns preserved; the complex has mostly disappeared | Abandoned structures | Outskirts of village | No reliable data |

| Location | Technical Condition | Construction Material | Building Form | Heritage Value | Development Potential |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lelów | Moderate; several wooden barns preserved; some overgrown and difficult to access. | Timber | Rectangular solid volumes with gable roofs | Significant element of the historical landscape due to the presence of surviving wooden structures. | Noticeable potential; possible adaptation for educational or tourism-related uses. |

| Mstów | Poor; mostly foundations and gable-end wall fragments remain. | Timber, Jurassic limestone | Rectangular solid volumes with gable roofs | Important component of the cultural landscape despite severe degradation. | High potential; possible revitalization and partial historical reconstruction. |

| Siewierz | Moderate; preserved structures lack roofs; walls in fair to poor condition. | Mainly brick with limestone elements | Rectangular solid volumes with gable roofs | Historically valuable complex with a well-preserved spatial layout. | High potential; feasible revitalization and functional adaptation. |

| Sławków | Moderate; brick buildings preserved with some limestone elements; visible damage. | Mainly brick with limestone elements | Rectangular solid volumes with gable roofs | Valuable landscape feature; significant preserved architectural details. | High potential; tourism and commercial functions could be introduced. |

| Żarki | Good; most barns are in use or partially used, roofs preserved, ongoing maintenance. | Jurassic limestone, brick used for reinforcement | Rectangular solid volumes with gable roofs | Very important and well-preserved architectural complex with high historical and aesthetic values. | Very high potential; currently partially used as a seasonal market. Further adaptation for commercial, residential, educational, and cultural use is viable. |

| Żarnowiec | Poor; only fragments of timber structures remain, heavily degraded. | Timber | Rectangular solid volumes with gable roofs | Component of the cultural landscape; retains historical value despite major damage. | Noticeable potential; suitable for educational and interpretive purposes. |

| Aspect | Residents | Experts |

|---|---|---|

| Perception of historical value | Older generations recognize historical value and link barns with local traditions; younger people often see them as obsolete structures. | High appreciation of historical value; barn districts seen as testimonies to past urban and economic structures. |

| Technical condition and renovation needs | Opinions are divided: some support preservation, others favor demolition or radical redevelopment. | Preserving historic fabric is essential; investment decisions should be based on technical condition and location. |

| Usability potential | Lack of a coherent vision for future use; residents often cite limited adaptability and low functionality. | Recognized adaptive reuse potential for cultural, educational, tourism, and mixed-use purposes; flexibility often limited by conservation regulations. |

| Significance for local identity | Barns are seen as important for identity and memory by older residents; younger residents show less interest in preservation or reuse. | Barns are considered key elements of cultural and urban heritage that can foster place-based identity. |

| Perception by outsiders | Some residents note that outsiders find barns unique and architecturally distinct compared to modern buildings. | Acknowledged for their unique architectural and landscape value; seen as underused cultural and tourism assets. |

| Investment challenges | Limited awareness of formal protection needs and investment challenges. | Revitalization requires compliance with heritage guidelines; economic barriers and lack of investment models; public–private partnerships and municipal strategies are needed. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Komarzyńska-Świeściak, E.; Wancel, A.A. Reintegrating Marginalized Rural Heritage: The Adaptive Potential of Barn Districts in Central Europe’s Cultural Landscapes. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157166

Komarzyńska-Świeściak E, Wancel AA. Reintegrating Marginalized Rural Heritage: The Adaptive Potential of Barn Districts in Central Europe’s Cultural Landscapes. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):7166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157166

Chicago/Turabian StyleKomarzyńska-Świeściak, Elżbieta, and Anna Alicja Wancel. 2025. "Reintegrating Marginalized Rural Heritage: The Adaptive Potential of Barn Districts in Central Europe’s Cultural Landscapes" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 7166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157166

APA StyleKomarzyńska-Świeściak, E., & Wancel, A. A. (2025). Reintegrating Marginalized Rural Heritage: The Adaptive Potential of Barn Districts in Central Europe’s Cultural Landscapes. Sustainability, 17(15), 7166. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157166