1. Introduction

The existing literature suggests that firms may adopt either defensive or offensive strategies when confronted with a crisis [

1]. Defensive actions include tighter budgets, cost cutting, and increased accountability [

2]. Instead, when dealing with offensive options, firms focus on opportunities for innovation [

3]. Crises can also create new opportunities [

4], and innovative and entrepreneurial companies can cultivate markets by developing new products or introducing new technologies [

5]. Ebersberger and Kuckertz (2021) [

6] examined how quickly different types of innovators responded to the opportunities and challenges posed by the COVID-19 crisis. They found that innovative companies are the quickest to react to the changing business environment. These companies actively explore opportunities during a crisis and are not constrained by a specific business model. In contrast, the history and path dependence of conservative companies may limit their search options.

Entrepreneurial orientation (EO), conceptualized as a risk-infused strategic disposition [

7], manifests through three constitutive dimensions: (a) innovation, (b) proactivity, and (c) risk-taking [

8]. Meta-analytic evidence confirms EO’s measurable influence on organizational growth trajectories, accounting for 18–22% of performance variance across industries [

9,

10]. This strategic posture operates as both a growth accelerator and performance differentiator, particularly in dynamic environments [

11]. Despite established insights into EO’s consequences, its antecedents in crisis contexts remain theoretically underspecified. As Wales et al. (2013) [

12] critically observes, “the genesis and sustenance mechanisms of entrepreneurially oriented organizations constitute persistent blind spots in strategic entrepreneurship research.” This gap becomes particularly salient when juxtaposed with behavioral agency theory’s proposition that performance nadirs—operationalized as attainment discrepancies relative to aspiration levels [

13]—may paradoxically trigger risk-laden strategic actions.

In developed economies such as the United States and Germany, firms have demonstrated greater agility and strategic adaptability in response to performance shortfalls, particularly under crisis conditions such as the 2008 global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior studies suggest that enterprises in these contexts often adopt proactive measures—including increased investments in innovation, digital transformation, and organizational renewal—to mitigate environmental threats and maintain competitive viability [

14]. In contrast, firms in emerging markets are frequently subject to heightened institutional volatility and resource constraints, which may reshape the mechanisms through which performance feedback influences strategic decision-making processes [

15]. As the largest emerging economy, China presents a distinct institutional configuration and a rapidly evolving digital infrastructure, offering a representative and contextually rich setting to investigate how firms formulate strategic responses to performance shortfalls. Accordingly, this study contributes to a deeper understanding of how firms across different national environments develop crisis-responsive strategic behaviors, thereby enriching the comparative literature on decision-making under environmental adversity.

Organizational performance relative to desired levels can elucidate how organizations initiate or terminate a wide range of strategic activities [

16,

17]. In the long run, consistently achieving performance above desired levels is essential for organizations to survive and thrive, while consistently falling below desired levels can pose significant challenges. Consequently, performance that is below aspirations typically motivates organizations to seek activities that can enhance performance. In other words, it triggers a problemistic search to address underperformance. Scholars have examined how organizations adjust the intensity of R&D, product innovation, investment, growth, and other strategic changes in response to negative performance feedback [

18]. However, EO has received relatively little attention to date. It has been suggested that when companies do not meet performance aspiration, they may place greater emphasis on enhancing their EO. In such cases, organizations recognize the need for change, leading to a new approach to business [

19]. This shift can accelerate risk-taking and experimentation in search of innovative solutions.

Despite general empirical support for firms’ responses to performance feedback, recent research has begun to recognize that a deeper understanding of the impact of performance feedback on firm behavior requires consideration of moderating factors. Audia and Greve (2006) [

20] show that negative achievement differentials reduce risk-taking behavior in small firms while increasing it in large firms. Vissa et al. (2010) [

21] found that organizational form influences the response to performance feedback, depending on the type of search field. These studies suggest that richer theoretical insights into the link between performance feedback and firm decision outcomes can be gained by examining the moderators. However, the role of managerial cognitive biases in this context has yet to be explored. Given that behavioral theory emphasizes the risky choices made by firm decision-makers, and that firms’ risky behavioral activism may be constrained by management’s cognition [

22], we argue managerial cognitive biases are critical factors to consider. The contribution of our study to the existing literature is twofold. First, it addresses the call for performance feedback as an antecedent of EO [

12,

23]. In doing so, this study also contributes to and extends the literature on the dynamic nature of EO [

24,

25], representing a novel application of behavioral theory of the firm. Second, overconfidence and myopia are recognized as the most pervasive and influential managerial biases in existing research. It significantly shapes how individuals perceive and interpret information, ultimately influencing their decision-making behavior. By incorporating them into the performance feedback literature as a previously underexplored factor, we offer fresh perspectives on how performance shortfalls are interpreted. More broadly, it contributes to a deeper understanding of the conditions under which the behavioral theory of the firm’s traditional predictions about firm risk-taking are upheld or potentially challenged.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Firms’ Response to Threats

An insider threat is defined as “any form of dramatic reduction in financial and/or reputational well-being” [

26]. However, some recent studies have moved away from this strict definition, arguing that any decline in a company’s performance can serve as a stimulus for a “glass cliff” [

27]. Returning to the initial conceptualization of threat, this study defines a firm’s insider threat as the gap between its actual performance and its desired performance [

25,

26]. The literature suggests that firms may alter their typically conservative tendencies when their growth status is threatened. This change occurs to avoid remaining passive in the face of a larger predicament, prompting firms to adapt their existing practices [

28], such as experimenting with new technologies or markets [

29], investing more in R&D [

30], or reorganizing the firm [

31]. Additionally, the literature indicates that the pursuit of expected financial returns becomes more appealing to adversarial firms, as potential improvements in financial returns can help preserve the firm’s sustainable competitive advantage [

32].

Behavioral theory posits that comparisons of gain and loss outcomes are always made relative to a reference point [

33]. A gain frame-when performance is above the reference point-prompts risk-averse strategic postures aimed at protecting gains [

28]. In contrast, a loss frame—when performance is below the reference point—encourages risk-seeking strategic postures [

34]. Consistent with the existing literature [

24,

35], this paper treats entrepreneurship as a practical resource allocation decision in the face of uncertain outcomes. Previous studies have characterized various strategic choices, including venture and divestment [

34], capital investment [

35], new market entry [

36], mergers and acquisitions [

36], and investment in innovation [

37]. This study uses EO as a proxy for risky strategic posture, as it can lead to uncertain outcomes [

9]. EO is defined as “the organizational processes, methods, and styles that firms use to conduct entrepreneurial activities” [

38] and is regarded as a strategic posture and behavior that involves innovation, proactivity, and risk-taking [

39], with the aim of creating a competitive advantage. While the external environment influences EO [

40], it is typically associated with a firm’s strategic responsiveness—its ability to readjust its strategy to align with the environment. Internal factors, such as the business conditions of the firm, also play a crucial role in shaping EO [

12].

2.2. Performance Shortfalls and EO

Kahneman and Tversky (1979) [

41] criticized the traditional assumption of rationality in classical economics by highlighting that individuals exhibit different attitudes towards risk depending on the context. This distinction clarifies the observation that people tend to be risk-averse in positive situations and risk-seeking in negative situations. These opposing preferences are referred to as “reflexive effects” [

33]. Consequently, managers facing threats may exhibit both risk-seeking and risk-averse behaviors. In their study on management’s attitudes toward risk, March and Shapira (1987) [

42] argued that managers tend to be risk-averse when organizational performance is strong. Conversely, they are more inclined to make riskier choices in response to organizational failures. Arguments from behavior theory suggest that when faced with a negative achievement gap, decision-makers recognize that the company is not keeping pace with the competition and, therefore, engages in problem searches aimed at closing the performance gap. Consistent with most research in the field of firm behavior, this study focuses on firms’ responses to below-aspiration performance. Specifically, a lack of clarity regarding the reasons for negative achievement gaps may encourage decision-makers to commit to broad strategic activities that involve some degree of risk, such as venture capital investments.

Research in the field of intrapreneurial venture capital indicates that the poor performance in a firm’s core business can motivate the firm to seek growth opportunities in more attractive market segments. Similarly, underperformance relative to peers may drive firms to search for new technologies or capabilities that could enhance their competitive efforts [

43]. In both cases, the broad scanning nature of entrepreneurial behavior enables firms to respond effectively to the challenge of relative underperformance. Cyert and March (1963) [

19] suggested that search activities are driven by specific problems related to underperformance. According to the behavior theory, firms evaluate their performance against desirable reference points, which include both historical ambitions—reflecting the firm’s past financial performance—and the firm’s current performance relative to its peers [

19]. It has been argued that performance below historical aspiration (HPA) or societal aspiration (SPA) triggers problematic exploration among decision-makers who seek solutions to address performance shortfalls, leading to increased risk-taking behavior. Conversely, when performance exceeds aspiration, decision-makers tend to be more risk-averse. This higher performance often results in a “complacency” or “status quo effect,” making firms less likely to engage in risky activities [

44,

45].

Previous research has highlighted the connection between performance shortfalls and organizational change [

46], international entrepreneurship [

18], and strategic repositioning. When confronted with significant performance shortfalls, managers recognize that the current strategy is failing to deliver the required level of performance. However, due to a lack of clarity regarding the reasons behind the company’s underperformance, they often resort to risk-oriented strategic activities [

44]. Consequently, companies begin to alter their strategic posture to address issues in their current operations [

18]. This exploration uncovers strategic options for diversification and innovation [

46]. In other words, when performance falls short, one approach is to modify internal activities in search of new products, markets, and strategies. While the initial search may focus on the current situation, subsequent efforts may lead the firm into new business areas, both of which align with a higher EO. Thus, the greater the performance shortfalls, the more likely the firm will broaden its search for business solutions, demonstrating an elevated EO.

Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1a. Historical performance shortfalls promote EO.

H1b. Social performance shortfalls promote EO.

2.3. The Moderating Effects of Managerial Overconfidence

Overconfidence is a significant cognitive bias [

47]. Generally, individuals demonstrate the highest levels of overconfidence in actions to which they are deeply committed [

48] and tend to believe that outcomes are under their control. This phenomenon is particularly relevant for managers who are highly motivated to achieve positive results for their firms and possess considerable discretion over financial strategies. Importantly, like other cognitive biases, the extent and nature of overconfidence can vary significantly among individuals. Numerous empirical studies have consistently linked managerial overconfidence to various firm outcomes, including acquisitions [

49], innovation, and corporate social responsibility [

50]. Furthermore, prior theoretical and empirical studies have established that overconfidence exerts a substantial influence on individuals’ processing and interpretation of information pertaining to their past performance, thereby impacting subsequent decision-making [

51]. This highlights the critical role of overconfidence in responding to performance feedback [

52]. An increasing number of researchers are now delving into the cognitive mechanisms that underlie entrepreneurial behavior. For example, Gudmundsson and Lechner (2013) [

53] investigated the effects of various factors, including overconfidence, optimism bias, and trust bias, on the survival of startups. Additionally, Wong et al. (2017) [

54] explored the implications of CEO overconfidence for innovation duality.

Due to their exaggerated perceptions of managerial capabilities, overconfident managers are likely to interpret the firm’s anticipated future performance as more favorable than it objectively is, regardless of the level of performance feedback. Overconfident managers confronted with negative feedback may erroneously believe that remaining in a low-risk strategy, which effectively “locks in” expected returns, is the optimal approach to achieve the desired performance outcomes. Consequently, they may perceive less urgency to escalate entrepreneurial activities. In essence, overconfident managers are inclined to pursue innovative and risky strategies only in the presence of significant negative performance feedback; otherwise, they may mistakenly assume that reliance on established operational procedures will suffice to meet their performance objectives. Therefore, this study posits that overconfident managers are likely to perceive negative performance feedback as less severe than their non-overconfident counterparts, resulting in a diminished impact of such feedback on their decision-making processes.

Accordingly, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2a. The relationship between EO and historical performance shortfalls is moderated by managerial overconfidence, such that the impact of historical performance shortfalls on EO will be less positive for overconfident managers.

H2b. The relationship between EO and social performance shortfalls is moderated by managerial overconfidence, such that the impact of social performance shortfalls on EO will be less positive for overconfident managers.

2.4. The Moderating Effects of Managerial Myopia

Temporal orientation is an unconscious cognitive process that reflects the extent to which individuals prefer past, present, and future considerations in strategic decision-making [

55]. Specifically, a myopic orientation among managers refers to their predominant focus on immediate concerns [

56]. This inclination towards myopia thinking often results in myopic decision-making, wherein managers prioritize current benefits at the expense of the firm’s long-term development. From a social psychology perspective, temporal orientation is viewed as an intrinsic and stable personal characteristic [

57]. When management displays myopic cognitive biases, the firm’s strategies and managerial practices are likely to become overly focused on short-term gains, thereby potentially jeopardizing its long-term viability.

EO is inherently characterized by high levels of investment, risk, and uncertainty. While a robust entrepreneurial orientation can catalyze innovation and growth, it also demands significant resources and can divert managerial attention. Furthermore, short-term performance pressures can adversely affect the firm’s stock price. In order to protect their interests and mitigate potential declines in stock value, myopic management teams may feel compelled to utilize their authority to obstruct the development of an entrepreneurial orientation. Although performance shortfalls can trigger problem searches that encourage a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation, short-sighted managers may resist or even impede the implementation of such initiatives when viewed through the lens of their self-interests. This myopia ultimately reduces the firm’s willingness to engage in entrepreneurial activities during periods of adversity, thereby diminishing the overall level of entrepreneurial orientation.

Based on this analysis, the study proposes the following hypothesis:

H3a. The relationship between EO and historical performance shortfalls is moderated by managerial myopia. Specifically, the impact of historical performance shortfalls on EO is less positive for myopic management.

H3b. The relationship between EO and societal performance shortfalls is moderated by managerial myopia. Specifically, the impact of societal performance shortfalls on EO is less positive for myopic management.

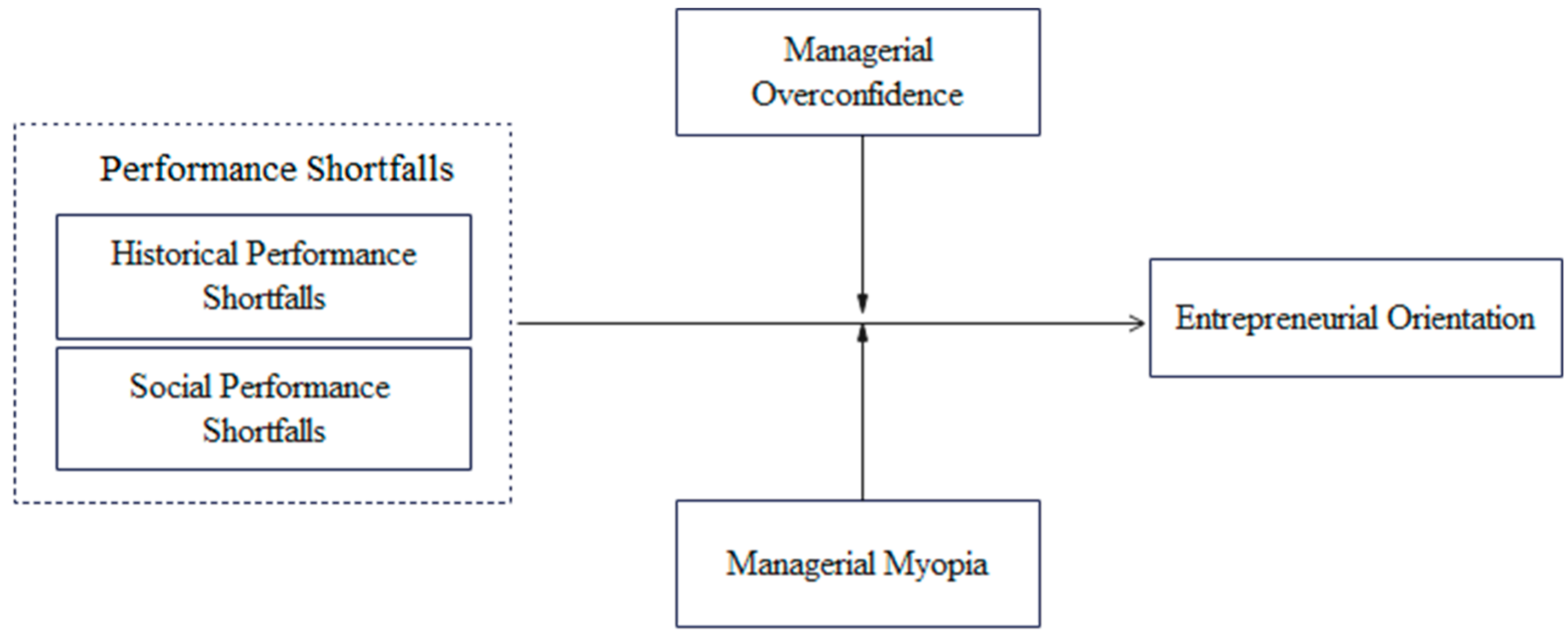

Our hypothesized relationships are graphically summarized in

Figure 1, which outlines the study’s conceptual framework. In this model, performance shortfalls—both historical performance shortfalls and social performance shortfalls—are proposed to promote EO of the firm. These direct positive relationships correspond to Hypothesis 1a and 1b. Additionally,

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed moderating roles of two key managerial traits: managerial overconfidence and managerial myopia. As indicated by the downward arrows from these moderator variables to the main effect path, we expect that these traits weaken the positive impact of performance shortfalls on EO. In other words, Hypotheses 2a and 2b posit that when a CEO is overly confident, the motivating effect of historical or social shortfalls on EO will be less positive. Similarly, Hypotheses 3a and 3b posit that a myopic manager will also attenuate the positive relationship between performance shortfalls and EO. This framework sets the stage for our hypothesis tests, with

Figure 1 visually depicting H1a–H3b.

5. Robustness Check

5.1. Dependent Variable Substitution

Based on existing research, we utilize the three aforementioned indicators of EO to reconstruct a comprehensive measure of entrepreneurial orientation intensity. These three indicators form different combinations within a three-dimensional probability space, with each combination corresponding to a distinct state of EO. This comprehensive indicator allows for a more thorough understanding of the complexity of EO and assists researchers and decision-makers in more accurately evaluating and analyzing the actual situation of EO. The specific calculation method is as follows: First, let

x represent the proportion of research and development expenditures to total assets for the

i-th company in year

t within the two-dimensional probability space,

y represent the percentage of annual earnings reinvested into the company (i.e., the proportion of retained earnings to total assets) for the

i company in year

t, and

z represent the level of earnings volatility for the

i-th company in year

t. Thus, (

x,

y,

z) reflects the EO state of the

i-th company in year

t. Second, calculate the Euclidean distance from the origin (0, 0, 0) to the entrepreneurial orientation (

x,

y,

z) of the

i-th company in year

t. The square root of this distance is defined as the intensity of the company’s EO. The formula is as follows:

The smaller the value of

Entrepreneurial_Orientation, the lower the EO intensity; conversely, a higher value indicates stronger EO intensity. In other words, the closer the EO position is to (0, 0, 0) in the three-dimensional space, the weaker the EO; the farther the position is from (0, 0, 0), the stronger the EO. Regression analysis was conducted on the performance shortfalls and EO after replacing the measurement method. The results are shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

Table 6 presents the regression results of the historical performance shortfalls and EO, while

Table 7 presents the regression results of the social performance shortfalls and EO. From the results, it can be observed that the findings remain robust after the replacement of the EO measurement method.

5.2. Controlling for Correlated Independent Variables

To further ensure the robustness of the research results, this study addresses the relatively high correlation between the independent variables—historical performance shortfalls and social performance shortfalls. Given the potential strong association between the two, this study takes further consideration when examining the relationship between performance shortfalls and EO. Specifically, when analyzing the impact of historical performance shortfalls, social performance shortfalls are included as a control variable in the model, and vice versa. The results continue to support the research hypotheses, confirming the robustness of the findings.

5.3. Endogeneity Analyses

Considering the potential endogeneity issues between performance shortfalls and EO, we employed the propensity score matching (PSM) method to conduct robustness tests on the hypotheses. We constructed a dummy variable based on the mean of the performance shortfalls; if the performance shortfalls were above the mean, the dummy variable was assigned a value of 1; otherwise, it was assigned a value of 0, thereby categorizing companies into an experimental group and a control group. Next, we used the dummy variable as the dependent variable and all control variables included in the main regression as independent variables, employing a logit model for regression analysis to calculate the propensity scores for the observed samples. Following this, we performed matching between the experimental and control groups based on a 1-to-4 nearest neighbor matching principle. After matching, the standardized bias of all covariates was less than 10%, and most covariates did not exhibit significant differences post-matching. Finally, we conducted regression analysis on the successfully matched samples. Specifically, the regression coefficients for both the interaction of historical performance shortfalls and overconfidence/myopia, and the interaction of social performance shortfalls and overconfidence/myopia were significantly positive. This indicates that after employing the propensity score matching method to enhance comparability between samples, the research findings remain robust.

Given that the study’s results may be biased due to omitted variables or measurement errors, leading to endogeneity issues, this research adopts the instrumental variable method to address this potential problem. This study uses the industry-year mean of performance shortfalls as the instrumental variable. This instrumental variable satisfies both relevance and exogeneity conditions. The study conducted tests for weak instruments and over-identification, both of which met the requirements for selecting the instrumental variable. The results indicate that after considering the potential endogeneity between performance shortfalls and corporate EO, both historical performance shortfalls and social performance shortfalls still have positive coefficients with significance at the 1% level, demonstrating that performance shortfalls can significantly promote corporate EO, consistent with previous findings. This further verifies the robustness of the results in this study.

7. Conclusions, Policy Recommendations and Discussion

7.1. Conclusions and Contributions

This study set out to examine how internal organizational crises—specifically, performance shortfalls relative to aspirations—shape a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation (EO). Our findings confirm that internal performance threats can indeed act as a catalyst for entrepreneurial behavior. Firms operating below their aspiration levels tend to pursue more innovative, risk-taking, and proactive strategies, indicating that adversity within the organization can spur a search for new opportunities. This result extends the scope of EO research beyond external triggers (like market turbulence or disruptive events) to include internal triggers. In doing so, it demonstrates that EO is not solely a response to external pressures but also a deliberate strategic reaction to challenges arising from within the firm.

Our evidence aligns with core tenets of the Behavioral Theory of the Firm and prospect theory. When performance falls below targets, decision-makers appear more willing to deviate from the status quo, engage in problemistic search, and take strategic risks. This behavior supports the classic argument that organizations respond to performance shortfalls by seeking innovative solutions. By showing that firms increase EO when facing internal shortfalls, we provide empirical confirmation of this behavioral tendency within a strategic entrepreneurship context. Furthermore, we contribute to the theoretical debate on organizational responses to adversity. An alternative perspective, threat-rigidity theory, would predict that threats lead to conservatism and rigidity. In contrast, our results show a pattern of increased entrepreneurial action under internal threat. This suggests that, under the conditions we studied (moderate performance shortfalls rather than existential crises), the drive to recover and seize new opportunities outweighs any impulse to retreat. By suggesting that only more extreme threats trigger the paralysis described by threat-rigidity, this finding helps explain why some prior studies observed reduced risk-taking under severe threat while we observe the opposite in more moderate circumstances.

Beyond the overall effect of performance shortfalls, we uncover important sources of heterogeneity in how firms respond. Managerial cognitive biases emerged as critical contingent factors. Overconfident top managers significantly dampen the firm’s tendency to respond entrepreneurially to performance shortfalls. These leaders, due to unwarranted faith in their current strategies, may discount or ignore negative performance feedback, and thus they initiate fewer innovative or risky changes than their less overconfident counterparts. While overconfidence is often associated with higher general risk-taking, our findings nuance this view by showing that overconfidence can impede the specific adaptive risk-taking triggered by performance feedback. Similarly, managerial myopia weakens the positive relationship between performance shortfalls and EO. Myopic managers may prefer quick wins or cost-cutting to improve short-term metrics, rather than investing in new ventures or creative projects that pay off in the longer run. Together, these findings contribute a cognitive perspective to EO theory: performance feedback will spur entrepreneurial action only if decision-makers are psychologically willing to heed the warning signs and take a long-range view. We thereby explain one reason why some firms fail to pivot or innovate when performance declines—the biases of their leaders act as brakes on the very behaviors that the Behavioral Theory of the Firm would predict.

In addition to managerial traits, organizational context conditions the strength of EO responses to internal crises. Our results show that ownership structure matters: non-state-owned enterprises exhibited a much stronger increase in EO following performance shortfalls than state-owned enterprises. This likely reflects differences in incentives: non-state-owned firms face stronger profit pressures and competition, prompting bold action when goals are missed, whereas state-owned firms often have broader objectives and some degree of support or protection, reducing their urgency to innovate in response to shortfalls. Thus, the entrepreneurial drive triggered by internal shortfall is somewhat muted in state-owned enterprises. We also find that digital transformation plays a role: firms with greater digital maturity respond more entrepreneurially to shortfalls. Digital capabilities likely enable faster pivots and opportunity-seeking in the face of setbacks, whereas firms low in digital maturity lack the agility to mount such responses. These contextual findings underscore that the link between internal crisis and EO is not uniform across all organizations. It depends on the firm’s environment and resources. By identifying ownership type and digital capability as key moderators, our study reinforces a contingency view in entrepreneurship theory: the same trigger (performance shortfall) can lead to divergent outcomes depending on organizational context.

In sum, our research contributes to a deeper theoretical understanding of entrepreneurial orientation by integrating internal performance feedback into its antecedents and revealing how cognitive and contextual factors shape entrepreneurial responses. First, we establish internal performance shortfalls as a significant driver of EO, expanding the entrepreneurial orientation discourse beyond external environmental factors. Second, we clarify why firms may respond differently to similar performance shortfalls: managerial overconfidence and myopia can restrain the adaptive, opportunity-seeking behaviors that performance shortfalls would otherwise stimulate, while factors like non-state-owned ownership and digital readiness strengthen those behaviors. This helps explain inconsistencies in prior findings and demonstrates the value of incorporating cognitive and contextual lenses into behavioral theories of the firm.

Overall, this study enriches the conversation on why and when firms embrace an EO, showing that it is a dynamic strategic posture shaped not only by external shocks but also by internal triggers, tempered by who leads the firm and what resources the firm can leverage.

7.2. Policy and Managerial Recommendations

Our findings yield several actionable insights for managers and policymakers seeking to sustain competitive advantage amid performance shortfalls. First, for corporate executives and board members, the results highlight the importance of treating internal performance shortfalls as a catalyst for entrepreneurial action rather than a trigger for panic or retrenchment. When a firm underperforms relative to its aspirations, managers should resist any instinct to hide the problem or resort solely to conservative cutbacks. Instead, they can frame the shortfall as an opportunity to search for new strategies—for example, by launching internal reviews or task forces to generate innovative solutions. This proactive stance is more likely to yield turnaround ideas aligned with an EO, consistent with our evidence that moderate internal setbacks spur innovation.

Crucially, executives must also recognize and mitigate cognitive biases that our study found can dampen the positive effects of adversity. Managerial overconfidence can lead leaders to dismiss negative feedback or cling to the status quo, while managerial myopia may push them to seek quick fixes (such as cost cuts or one-off gains) at the expense of longer-term innovation. To counter overconfidence, companies could implement checks and balances in decision-making—such as encouraging open debates in leadership teams or bringing in independent advisors who can provide critical perspectives when performance flags. Firms may establish a series of processes to challenge entrenched strategies, ensuring that early warning signs are acknowledged rather than ignored. To combat short-termism, firms should align incentives and evaluation systems with long-run performance. This might include tying a portion of executive compensation to multi-year innovation milestones or future-oriented metrics, such as successful new product launches or R&D outcomes, rather than focusing solely on the next quarter’s profits. Such incentive structures encourage managers to pursue bold, forward-looking projects even when immediate results are underwhelming. By cultivating an organizational culture that values learning from failure and long-term vision, top leaders can turn a performance shortfall into a springboard for entrepreneurial renewal.

Additionally, our study underlines the role of organizational capabilities—notably, digital transformation—in enabling an effective entrepreneurial response to adversity. Firms with greater digital maturity, such as advanced IT systems, data analytics capabilities, and digitally skilled talent, were significantly more likely to respond to performance shortfalls with increased EO. For practitioners, this implies that investing in digital tools and infrastructure is not just a technological upgrade but a strategic buffer against turbulence. A digitally agile firm can more rapidly diagnose the causes of a performance decline and can more flexibly pivot operations or business models in response. Managers should therefore champion digital transformation initiatives in their organizations before a crisis hits—such as implementing data-driven decision platforms, fostering a workforce adept at digital technologies, and establishing agile processes—so that when internal challenges arise, the firm is equipped to innovate its way out of trouble.

From a policy and regulatory perspective, our findings offer guidance to those aiming to stimulate corporate entrepreneurship in China’s listed firms. One notable insight is the difference we observed between state-owned enterprises and non-state-owned enterprises: state-owned enterprises showed a weaker entrepreneurial response to performance shortfalls. Policymakers can address this gap by reforming incentive structures and governance in the state sector to mimic competitive, innovation-driven dynamics. For example, regulators or state owners could revise performance evaluation criteria for state-owned enterprises executives to place greater weight on innovation outcomes and adaptive responses to performance issues. Rewarding managers for entrepreneurial behaviors and holding them accountable when complacent during downturns would send a strong signal that adaptability and innovation are expected, even for firms with government ownership.

Finally, policymakers should continue promoting digital transformation at the national and industry levels. Targeted support policies, such as subsidies or tax incentives for investments in digital infrastructure and employee training, can lower adoption barriers and enhance firms’ agility in responding to performance issues.

7.3. Limitations and Future Directions

Like any other research, this paper has some limitations that could serve as viable directions for future studies. First, this study acknowledges the limitations of using secondary data, such as financial data from companies, to measure EO, as EO includes cognitive factors to some extent that secondary data can not fully capture. And using financial proxies to measure EO offers objective, longitudinal metrics, these indicators have inherent limitations. Financial proxies indirectly reflect entrepreneurial behaviors, potentially raising construct validity concerns. Similarly, earnings reinvestment as a measure of proactiveness might be influenced by external factors such as profitability constraints or dividend policies. Additionally, ROA volatility used for risk-taking could represent market conditions or management inefficiency rather than deliberate risk-taking. Therefore, future research could explore other methodologies to address current measurement issues related to EO, aiming for more accurate and comprehensive identification of EO, such as experimental methods. In addition, consistent with mainstream literature, this paper excluded sample firms in the financial sector and ST * listed companies. However, this does not imply that these firms do not engage in entrepreneurial activities. Thus, future research could expand the sample to enhance the generalizability of the findings.

Second, in this study, the explanation regarding overconfidence still cannot clearly attribute the research findings to management’s overestimation of capabilities rather than to overestimation of other factors affecting company performance. Future attempts to directly explore this issue would be an interesting direction, such as adopting survey-based methods to collect primary data, which would allow researchers to measure both overconfidence and personality optimism simultaneously, thus attempting to unravel these two closely related phenomena. This study focused only on performance-based aspiration levels. However, companies typically pay attention not only to financial goals but also to other objectives, such as company growth and innovation. Decision-makers in organizations are not always satisfied with merely avoiding bankruptcy or achieving performance levels determined by average industry performance; rather, they strive to achieve more ambitious goals, such as attaining industry leadership. Expanding the model and empirical research to explore how these alternative objectives influence EO and interact with cognitive biases and other organizational dilemmas would be highly meaningful.

Third, successful companies demonstrate the ability to learn and adapt during their development, but they may overlook environments that could lead to low commitment. Future research should further consider the impact of the surrounding environment to clarify the relationships among entrepreneurial behavior, performance outcomes, and the dominant logic within firms. In explaining organizational responses to performance feedback, this paper primarily focuses on the problem-search mechanism. However, existing studies have identified several other theoretical mechanisms, such as loss aversion, threat rigidity, and adaptive aspiration. Through these mechanisms, performance feedback can be translated into organizational actions. Therefore, future research could investigate different theoretical mechanisms and specific causal chains to explain how organizations respond to performance feedback.