Abstract

Under intensified downward economic pressures on the economy, technological innovation is playing a pivotal role in the development of Chinese enterprises. Employees’ psychological safety significantly influences their innovative behaviors, as a climate of psychological safety fosters greater willingness among staff to engage in voice behaviors. Guanxi with a team leader may decrease this effect. This study analyzed survey data from 263 employees of China’s private manufacturing enterprises to explore the moderating role of guanxi with a team leader in the relationship between psychological safety climate and voice behavior. Results showed that psychological safety climate was positively correlated with promotive and prohibitive voices, and employees with a higher psychological safety climate were more likely to develop voice behavior. Guanxi with team leaders negatively moderated the relationship between psychological safety climate and promotive and prohibitive voices, and the association between psychological safety climate and promotive and prohibitive voices was strong when guanxi with a team leader was weak. This study expands the scope of the application of guanxi, with team leaders as a moderating variable. It helps leaders focus on the psychological safety climate of employees, maintain harmonious and friendly interpersonal relationships with employees, enable employees to spontaneously contribute to the development of the organization, and enhance cohesion in the organization.

1. Introduction

The technological innovation of Chinese enterprises has markedly strengthened China’s influence in critical areas encompassing research and development (R&D) advancement, overseas market expansion, corporate social responsibility (CSR) fulfillment, and global competitiveness enhancement [1]. Amid China’s economic transformation and upgrading process, innovation is profoundly reshaping the paradigm of economic growth and has been positioned as the cornerstone of national development strategy. With the deepening implementation of innovation-driven development principles, the institutionalization of innovation mechanisms at the corporate level has emerged as a pivotal lever for catalyzing industrial transformation, infusing sustained momentum into high-quality economic development [2].

Chinese technology innovation enterprises have made progress, but the process of becoming an innovative country is challenging [3]. Sustaining competitive innovation capabilities while aligning with organizational objectives presents a critical research agenda demanding deeper exploration. In an organization’s business environment, employees perceive social conditions as a result of concerns about job stability and psychological safety, and managers must respond positively to promote the achievement of organizational goals [4,5]. Organizations need employees to contribute to their sustainable development through voice behavior, innovation, or collaboration [6,7]; however, participation in such activities may pose risks to individual employees [7]. Among them, voice behavior may harm the vested interests of other members of the organization and challenge existing ways of doing business [8,9,10]. Voice behavior refers to the behavior of employees choosing to speak about their thoughts or provide potentially useful information in the face of situations in an organization [11,12]. The nature of this communication is constructive and change-oriented [13]. Voice behavior is important because, in an organizational operating and development environment, ideas for improvement and innovation cannot come from top management alone [10,12,14].

Employee voice behavior has been found to significantly correlate with innovation and, in certain conditions, may directly contribute to innovative behaviors within organizations, particularly when contextual factors such as job autonomy are present [15,16]. New ideas can help promote the continuous development and innovation of an organization and may support goal achievement when the organizational environment is conducive to such behavior [17,18,19]. Voice behavior and the opportunity to express opinions have also been shown to be associated with a sense of fairness, though this relationship is influenced by contextual factors such as leadership style and perceived organizational justice [20,21]. Moreover, voice behavior has been linked to supervisors’ evaluations of subordinates’ performance in contexts where openness is encouraged [18,22]. Therefore, it is important for organizations—especially those seeking to foster a harmonious and proactive work climate—to consider the enabling conditions under which employee voice is likely to flourish and contribute to a positive cycle of innovation and feedback [23,24]. Prior studies have identified factors such as job satisfaction [25], self-efficacy [26], and personality traits [27] as influential in shaping employees’ willingness to speak up.

Psychological safety mediates the influence of leaders’ personality traits on employee behavior [28,29]; when a leader’s inclusivity makes employees feel safe, they are more likely to speak freely, present ideas, and disclose mistakes [30]. Psychological safety refers to the degree to which individuals feel safe and confident in their ability to manage change [31,32] and is also defined as a shared belief among individuals about whether it is safe to engage in interpersonal risk taking in the workplace [33]. According to previous studies, psychological safety not only affects interpersonal communication between team members [34,35], knowledge sharing [36,37,38], and learning behavior [39,40] but also leads to more voice behavior among employees [41,42]. Employees are more likely to engage in voice behavior and report mistakes when they are not worried about their ideas, concerns, or mistakes being rejected, opposed, or blamed [30,43,44]. To promote an increase in employees’ voice behavior, organizations and managers should provide employees with a positive and trusting work environment that encourages them to engage in more open communication, feel safe to experiment with and take risks, and express concerns and suggestions to the organization [24,45,46]. Previous studies have confirmed that psychological safety is an important prerequisite for employees’ voice behavior and reporting errors in organizations [43,47,48]. Psychological safety serves as a foundational enabler of employee voice behavior. This voice behavior reciprocally strengthens work engagement in psychologically safe environments, creating a virtuous cycle that drives performance enhancement and innovation acceleration [49,50]; therefore, this study predicts that psychological safety will have a similar effect on voice behavior in the Chinese social context.

Additionally, this study suggests that guanxi with a team leader moderates the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior. In an organizational context, a relationship refers to an employee’s perception of the quality of the working relationship, which determines expected behavior and reciprocal treatment [51]. Chen and Tjosvold [52] described a “personal relationship” from a personal perspective as a private mode of communication and exchange through which people connect with each other. In the context of Chinese society, guanxi describes the implicit social ties or binary relationships between individuals based on common interests and advantages [53,54,55,56]; formal, official working relationships are difficult to distinguish from informal, unofficial leader–employee relationships [57]. According to previous studies, these relationships affect turnover rates [58], job performance [58,59], and open communication [60]. In addition, stable relationships between leaders and employees are associated with high levels of trust in leaders [61,62,63], which can lead to higher levels of organizational citizenship [58]. Employees with a stable relationship with their leaders can receive leadership support, which, in turn, reduces their work stress [64] and negative emotions [65,66,67]. In this work environment, employees tend to have higher job satisfaction [68] and increased organizational commitment [69,70], generating more suggestive behavior [66,71]. Whereas previous research (e.g., [72]) has examined the negative influence of guanxi-based HRM practices on employee voice via reduced job meaningfulness, our study investigates guanxi in the form of interpersonal relationships with team leaders as a contextual moderator, revealing that such relationships can dampen the positive effects of a psychologically safe climate on voice behavior. This study suggests that relationships with leaders reduce employees’ psychological safety needs and support their voice behavior. Therefore, this study predicts that guanxi between leaders and employees negatively moderates the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior in the Chinese social context; the importance of psychological safety to employees’ voice behavior is relatively weak when guanxi between leaders and employees is strong, and the importance of psychological safety to employees’ voice behavior is relatively high when the relationship between leaders and employees is weak.

Based on the above theories and a review of previous research, it was found that there have been many studies on the antecedents and outcomes of psychological safety, voice behavior, and relationships [73,74]; however, there were few studies on psychological safety and voice behavior in the Chinese social context, especially among Chinese technological innovation enterprises. Therefore, this study aims to explore whether psychological safety is associated with employees’ voice behavior in the Chinese social context and how guanxi with leaders plays a role in the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Backgrounds

The deterioration of the global economy due to major shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and interstate conflicts has exacerbated uncertainty and systemic risks in business environments. This turbulence intensifies employees’ perceived job insecurity and elevates anxiety levels about unemployment, which in turn adversely impacts organizational innovation and operational performance. Consequently, cultivating a psychological safety climate within enterprises has become imperative to mitigate these psychosocial stressors and sustain workforce engagement [75].

Psychological safety refers to the “extent to which individuals believe their colleagues (e.g., supervisors and coworkers) will not punish or misunderstand them for taking risks, such as speaking up with suggestions or concerns” [76]. Psychological safety climate refers to the atmosphere in an organization in which psychological safety is guaranteed [77,78]. In the field of organizational studies, there is a growing interest in the concept of atmospheric intensity, focusing on how perception forms or does not form consensus [79] and the impact on organizational outcomes [80]. Organizational psychological safety climate is often interpreted as a shared perception among members of the organization [45], which stems from members’ assessment of interpersonal risks in the organization [81]. Team climate reflects an individual’s shared perception of all aspects of an organization and leads to a variety of important team and individual-level outcomes [79,82]. The collaborative nature of work is a factor driving psychological safety research [83]. Studies have shown that fault tolerance helps employees see mistakes as an opportunity to learn rather than a threat to their image, so fault tolerance has a positive impact on psychological safety [84]. In addition, studies have shown that the prosocial motivation of leaders provides employees with the cognitive and emotional needs to thrive at work, with a positive indirect impact on employees’ psychological safety [85]. Changes in leader effectiveness and structural differences between organizations can explain the differences in mechanisms of vocal behavior within and between organizations, which affect the psychological safety climate of organizations [41]. Some scholars have discussed the basic issues of psychological safety dynamics at the group level. Empirical studies by Koopmann et al. [86] show that there is a curvilinear relationship between organizational tenure and organizational psychological safety climate and climate intensity, and psychological safety moderates the indirect curve relationship between organizational tenure and creative performance. According to previous research, psychological safety climate has an impact on organizational knowledge creation [87], organizational learning [88], organizational performance [47,82] and voice behavior [89]. Performance-focused research highlights the role of psychological safety in unlocking an individual’s potential to achieve their goals [83]. Psychological safety helps employees perceive needs as positive challenges and encourages employees to see challenges as opportunities to explore new ideas and take action [83,90].

Voice behavior is defined as a discretionary, change-oriented communication behavior in which employees proactively express their thoughts, concerns, or potentially valuable suggestions regarding work-related issues within the organization [11,12]. Voice behavior is commonly categorized into two distinct types: promotive voice and prohibitive voice. Promotive voice involves the expression of constructive ideas aimed at improving organizational functioning, while prohibitive voice refers to the expression of concerns about practices, behaviors, or incidents that may harm the organization. These two forms differ in both purpose and perceived risk and may be influenced by different psychological and contextual factors. Nevertheless, both behaviors are inherently constructive in nature, aimed at promoting improvements rather than mere criticism [13]. The significance of voice behavior lies in the fact that organizational innovation and performance enhancement cannot rely solely on top-down directives from management [10,14]. Instead, bottom-up contributions from employees are essential for identifying problems, generating novel ideas, and sustaining continuous improvement processes. Empirical research has consistently demonstrated a positive association between voice behavior and innovation. Under specific conditions—such as the presence of job autonomy—voice behavior may even serve as a direct antecedent of innovative work behavior [15,16]. When the organizational context is supportive, the articulation of new ideas by employees can contribute meaningfully to the achievement of strategic goals and ongoing innovation [17,18,19].

Furthermore, employee voice has been linked to perceptions of organizational justice and fairness, particularly when employees are given genuine opportunities to express their opinions [20,21]. This association, however, is context-dependent and may be influenced by leadership style and the perceived receptiveness of organizational systems. Voice behavior has also been found to influence supervisors’ evaluations of subordinates’ performance, especially in cultures or environments where open communication is encouraged and rewarded [18,22]. Given these findings, it is imperative for organizations—particularly those aiming to cultivate innovative and inclusive workplaces—to foster conditions that facilitate voice behavior. These enabling conditions include, but are not limited to, supportive leadership, psychologically safe environments, and a culture that values constructive feedback [23,24]. In addition, prior studies have identified several individual and contextual antecedents of voice behavior, including job satisfaction [25], self-efficacy [26], and personality traits [27].

2.2. Impact of Psychological Safety Climate on Voice Behaviors in the Chinese Context

Individuals in an organization determine their voice behavior based on whether the results of their behavior are positive or negative [73]. Organization members are more likely to express their opinions if they feel that they can express their advice without fear of criticism or embarrassment [82]. They seldom speak up if their safety in the organization is threatened by their behavior. Therefore, psychological safety is based on a cognitive assessment of whether a person can be themselves without fear of negative effects [91]. Employees with high levels of psychological safety are more likely to seek feedback from colleagues [92] and engage in helpful behaviors [25]. To induce employees’ voice behavior, organizations should eliminate the fear and concern that their actions will be punished [10,45,93]. Voice behavior refers to actively challenging the status quo and making constructive suggestions [87]. In the Chinese social context, employees tend to adhere to social or organizational norms when communicating with their leaders, rather than coming up with new ideas that may challenge these norms, because voice behavior can disrupt harmony and cause embarrassment [94,95]. Several empirical studies conducted on various international samples have shown that a psychological safety climate encourages voice behavior of organizational members [50,96]. According to Walumba and Schaubroeck [28], who conducted an empirical analysis of 894 employees belonging to 222 units in U.S. companies, employees who perceived a high level of psychological safety were more likely to speak up at their workplace. Similarly, Detert and Burris [10] analyzed 3149 employees and 223 managers in a U.S. restaurant chain and found that perceived psychological safety mediated the relationship between change-oriented leader behaviors and subordinates’ voice behaviors. In the healthcare field, a psychological safe climate allows healthcare professionals to express concern for patients [97] and report adverse events [43]. Morrison et al. [98] surveyed engineers in India and found that a more positive voice climate resulted in greater voice behavior by subordinates through using the concept of voice climate, which was similar to psychological safety.

Based on the above explanations, we argue that a psychological safety climate plays a pivotal role in facilitating both types of voice behavior, particularly in the Chinese organizational context, which is shaped by hierarchical norms and collectivist values. According to Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory [99], suggesting a cultural tendency to embrace change and delayed rewards over short-term conservatism [100,101]. Employees in such cultures are more likely to take interpersonal risks—such as speaking up—if they perceive their environment as safe and non-punitive [102,103]. In the case of promotive voice, psychological safety lowers the perceived interpersonal cost of proposing new ideas or improvements. Employees are more willing to offer suggestions for change when they believe their input will be welcomed rather than punished.

Hypothesis 1 (H1a).

Psychological safety climate is positively associated with promotive voice behavior in the Chinese context.

For prohibitive voice, which often entails identifying risks or pointing out problematic issues, the psychological cost can be higher, especially in high power-distance cultures like China. However, when employees perceive a high level of psychological safety, they are more likely to express concerns without fear of retaliation or social sanction [103,104]. In such cultural contexts, raising concerns may be perceived as a challenge to managerial authority or competence, potentially causing the manager to “lose face”. This fear of causing embarrassment or undermining the manager’s social standing acts as a significant barrier to expressing prohibitive voice. However, when employees perceive a high level of psychological safety climate, they are more likely to believe that voicing concerns will not lead to interpersonal conflict or negative repercussions. Psychological safety helps to mitigate fears related to face-threatening consequences by fostering a supportive environment where employees feel respected and valued, even when they speak up about problems or risks [104,105]. As such, a strong psychological safety climate is especially critical in encouraging prohibitive voice in face-sensitive, hierarchical cultures. Thus, we hypothesize as follows.

Hypothesis 1 (H1b).

Psychological safety climate is positively associated with prohibitive voice behavior in the Chinese context.

2.3. Moderating Role of Guanxi with Leaders

Guanxi is a unique characteristic of human relations in China and is formed based on Confucian culture [104]. Specifically, guanxi is defined as an “informal, personal connection between two individuals bounded by an implicit psychological contract to follow the social norms of guanxi, such as maintaining a long-term relationship, mutual commitment, loyalty, and obligation” [60]. The relationship process depends on the characteristics that each person brings to the relationship [94,105,106]. Guanxi with leaders refers to the interpersonal relationships between leaders and subordinates that facilitate a mutual network of interpersonal trust and consensus through formal or informal exchanges [107,108]. As Chinese leaders tend to be ambiguous in the balance between formal and informal relationships, the extent of guanxi with leaders affects the quality of exchange between leaders and subordinates in China [109]. Empirical studies conducted in China substantiate that leader–subordinate relationships exert significant influence on work-related psychological states and activities [60,110,111]—exemplified by fostering employees’ psychological ownership and driving innovative behaviors [112]. The value of achievement emphasizes social recognition by demonstrating competence in accordance with prevailing cultural standards [94,113]. In an organizational environment that values achievement, employees tend to actively demonstrate successful performance in their interactions with leaders and colleagues [94]. Based on LMX theory, leadership is not only based on the traits, styles, and behaviors of a leader or employee, but is rather a two-way relationship between a leader and an employee [114]. The rationale of LMX is that different types of exchange relationships develop between leaders and employees [115]. High-quality LMX relationships create a safe atmosphere that ensures that employees express new ideas to leaders without negatively impacting them, so employees are more likely to come up with new ideas [6,94]. In this case, employees have access to the leader’s relationships and resources, and this supportive, harmonious atmosphere is especially important for employees from Asian countries, where conflict avoidance is seen as a cultural value [87]. In summary, in China, employees tend to secure a stable and safe work life and have advantages in many areas when forming good guanxi with their leaders.

Therefore, we expect that psychological safety climate and guanxi play a substitutive role. According to the COR theory [116], individuals strive to acquire, retain, and protect valuable resources, and the accumulation of such resources provides a buffering effect against future losses (Resource Gain Principle). In this context, guanxi with a leader can be considered a social resource that provides employees with psychological assurance and informal protection. Therefore, when employees have strong guanxi with their leaders, they already possess a significant relational resource that makes them feel secure enough to engage in voice behaviors—even in the absence of formal psychological safety climates. Conversely, when guanxi is weak or absent, employees lack interpersonal protection and are more reliant on institutional resources, such as a formal psychological safety climate, to feel safe enough to express their opinions. In other words, psychological safety climate and guanxi act as substitutable resources: when one is lacking, the other becomes more critical in enabling voice behavior. Thus, consistent with the COR theory, when employees are deprived of guanxi, they seek to compensate by relying on the institutional resource of a safe climate, and vice versa.

In other words, the importance of psychological safety is relatively low when guanxi with a leader is strong, and vice versa; the importance of psychological safety is expected to be emphasized when guanxi with a leader is weak. Specifically, employees feel a sense of security in their organization and employment when they form guanxi with their leaders [117]. In other words, regardless of how their colleagues think, employees who have formed good relationships with their leaders become comfortable with their voice behavior [118,119]. Conversely, employees who do not form guanxi with their leaders want to be protected by institutional arrangements and discipline [120,121]. In other words, they provide suggestions only in a culture in which safety is assured by institutional backgrounds. As there is no leader to protect them from speech damage, the institutional situation or cultural atmosphere is more important [122]. Therefore, the importance of psychological safety is emphasized when guanxi between leaders is weak. Thus, we propose the following:

Hypothesis 2 (H2a).

Guanxi with a team leader negatively moderates the relationship between psychological safety climate and promotive voice behavior such that the association between psychological safety climate and promotive voice behavior is strong when guanxi with a team leader is weak.

Hypothesis 2 (H2b).

Guanxi with a team leader negatively moderates the relationship between psychological safety climate and prohibitive voice behavior such that the association between psychological safety climate and prohibitive voice behavior is strong when guanxi with a team leader is weak.

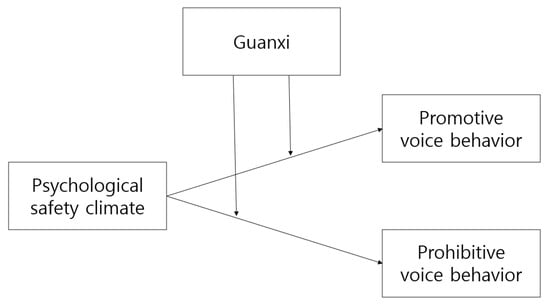

The above-stated hypothesis can be summarized as shown in Figure 1, which illustrates the research model.

Figure 1.

Research model.

3. Methodology

3.1. Sample

We surveyed private Chinese companies in the manufacturing industry. The survey was conducted on 14 manufacturing enterprises located in the Beijing, Shanghai, Hebei, and Shandong Provinces of China. Online questionnaires were administered to various staff levels. The questionnaires included employment environment, job-related attitudes, and perceptions of their relationship with their leaders. A total of 300 questionnaires were distributed and 270 questionnaires were received. After excluding questionnaires with missing values, a total of 263 valid questionnaires were used in the study. Of the participants, 43.89% were males and 56.11% were females. In terms of age, the majority of participants were under 30 years old, accounting for 50.39%; the next largest age group was 31–40, accounting for 32.83%; participants aged 41–50 accounted for 11.07%; and participants aged over 51 accounted for 5.73%. In terms of education level, the number of people with junior high school education was 4, accounting for 1.53%; the number of people with a high school degree was 9, accounting for 3.44%; the number of people with a college degree was 54, accounting for 20.61%. Of these latter participants, 56.11% had a bachelor’s degree; 16.79% had a master’s degree; and 1.53% had a doctorate degree or above. In terms of tenure in the company, 17.94% had less than 1 year; 43.13% had 2–5 years; 22.14% had 6–10 years; 11–15 years had 6.11%; 3.05% had 16–20 years; and 7.63% had more than 20 years.

The participants completed self-report surveys in Chinese, which is their native language. Using published multi-item measures with known psychometric properties, we followed established procedures for translating and back-translating measures and items. Except for several categorical variables such as sex, age, and education, all substantive variables were measured using a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

3.2. Variable Measurement

Psychological safety climate: Psychological safety climate was measured by averaging seven items based on Edmondson’s study [45] (e.g., “If someone made a mistake on this team, it was not held against him/her” and “It was safe to take a risk on this team”). The Cronbach alpha was 0.738.

Voice behavior: We used a 10-item scale developed by Liang and Farh [123] to measure individual voice behaviors such as promotive and prohibitive. The five items for measuring promotive voice behaviors include the following: “This employee proactively suggests new approaches that are beneficial to the change implementation processes”, “This employee raises suggestions to improve the change implementation processes”, “This employee proactively voices out constructive suggestions that improve the change implementation processes”, “This employee makes constructive suggestions to improve the change implementation processes”, and “This employee proactively develops and make suggestions for issues that may influence the change implementation processes”. Cronbach’s alpha for reliability was 0.855.

The other five items for measuring prohibitive voice behaviors include the following: “This employee dares to point out problems in the change implementation processes when they appear, even if that will hamper relationships with other colleagues”, “This employee speaks up honestly with problems in the change implementation processes that may cause serious loss to the organization, even when/though dissenting opinions exist”, “This employee proactively reports coordination problems in the change implementation processes to the management”, “This employee dares to voice out opinions on things that may affect efficiency of the change implementation processes in the organization, even if that will embarrass others”, and “This employee advises others against the undesirable change implementation processes that will hamper the change implementation”. Cronbach’s alpha for reliability was 0.890. We conducted a confirmatory factor analysis to test whether the two-factor model fitted the data. The results showed that the fit indices were within a relatively acceptable range (chi-square = 122.405, p < 0.001, GFI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.100, NFI = 0.915, and CFI = 0.937).

Guanxi with team leaders: To measure guanxi with team leaders, which is the moderating variable of this study, five items are used based on previous studies by Law et al. [65]. Sample items for guanxi with team leaders include the following: “During holidays or after office hours, I would call my supervisor or visit him/her”, “My supervisor invites me to his/her home for lunch or dinner”, “On special occasions such as my supervisor’s birthday, I would definitely visit my supervisor and send him/her gifts”, “I always actively share with my supervisor about my thoughts, problems, needs and feelings”, and “I care about and have a good understanding of my supervisor’s family and work conditions”. Cronbach’s alpha for reliability was 0.873.

Control variables: Several control variables that could affect outcome variables were added to the model. Males and females were dummy coded as 1 and 0, respectively. In terms of age, the respondents were asked to choose from 10-year periods. Thus, based on 20s as the reference group, 30s, 40s, and 50s were dummy coded and added to the model. Education level was reflected as a continuous variable by measuring the number of years each respondent belonged to the educational institution. The position was controlled by coding 1 if the respondent was a manager, and 0 otherwise. Tenure was also controlled for, reflecting the number of years currently at work.

Finally, a leader–member exchange (LMX) was added to control for the individual tendencies of the respondents’ leaders. We used the 11-item scale developed by Liden and Maslyn [124]. Sample items for measuring leader–member exchange include the following: “I like my supervisor very much as a person”, “My supervisor is the kind of person one would like to have as a friend”, “My supervisor is a lot of fun to work with”, “My supervisor defends my work actions to a superior, even without complete knowledge of the issue in question”, “My supervisor would come to my defense if I were ‘attacked’ by others”, “My supervisor would defend me to others in the organization if I made an honest mistake”, “I do work for my supervisor that goes beyond what is specified in my job description”, “I am willing to apply extra efforts, beyond those normally required, to further the interests of my work group”, “I am impressed with my supervisor’s knowledge of his/her job”, “I respect my supervisor’s knowledge of and competence on the job”, and “I admire my supervisor’s professional skills”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.904 (Appendix A).

3.3. Analysis Strategy

To empirically verify the statistical support for the given hypotheses, we analyzed them according to the following procedure: First, we conducted a regression using the ordinary least squares method by inserting control variables that could affect the two outcome variables (i.e., promotive and prohibitive voice behaviors). Second, the psychological safety climate variable was added to the previous model to confirm the direct effect of psychological safety (i.e., Hypotheses 1a and 1b) on each outcome variable. Finally, to verify the moderating effect of guanxi with a leader, the interaction terms of the psychological safety climate and guanxi with a leader were added to the model. In this case, if the interaction term was statistically significant, we tested whether the hypothesis was supported by checking how the control–effect pattern was derived through plotting.

To address the potential issue of common method bias (CMB), Harman’s single-factor test was conducted using all 40 survey items. An unrotated exploratory factor analysis was performed, and the results showed that the first factor accounted for 35.339% of the total variance, with an eigenvalue of 14.135. Since no single factor emerged to account for the majority of the variance (i.e., below the commonly accepted threshold of 50%), it was concluded that common method bias is not a significant concern in this study.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Analysis

The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables are presented in Table 1. As shown, the zero-order correlation between psychological safety climate and promotive voice behavior was 0.307 (p < 0.001) and psychological safety climate correlated with prohibitive voice behavior at 0.379 (p < 0.001). However, there was no statistical correlation with guanxi with leaders and promotive voice behavior or prohibitive voice behavior.

Table 1.

Mean, SD, and correlation matrix.

4.2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis

Table 2 presents the results of the hierarchical regression analysis. As explained in the Analysis Strategy section, the control variables included in Model 1 predict promotive voice behavior, and Model 4 predicts prohibitive voice behavior. Hypothesis 1a states that psychological safety climate is positively associated with promotive voice behavior in the Chinese context. Model 2 shows that psychological safety climate has a positive statistical relationship with promotive voice behavior (b = 0.342, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1a is supported. Hypothesis 1b states that psychological safety climate is positively associated with prohibitive voice behavior in the Chinese context. Model 5 of Table 2 shows that the psychological safety climate has a statistically positive relationship with prohibitive voice behavior (b = 0.432, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypothesis 1b is supported.

Table 2.

Results of hierarchical regression analysis.

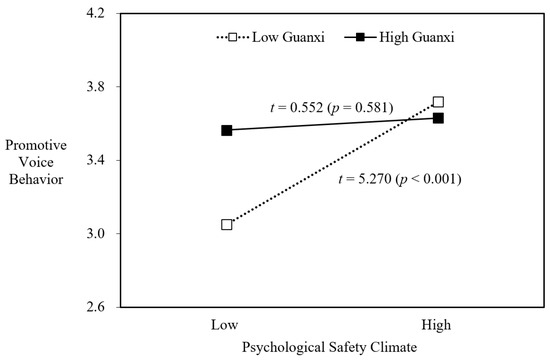

The results of verifying the moderating effect of guanxi with leaders on the relationship between psychological safety climate and voice behavior are as follows: As shown in Model 3 of Table 2, compared with Model 2, the interaction term of psychological safety climate and guanxi with team leaders was included in the model. Hypothesis 2a states that guanxi with team leaders negatively moderates the relationship between the psychological safety climate and promotive voice behavior. The result shows that the interaction term is statistically significant in a negative way (b = −0.293, p < 0.001). To interpret the results, we plotted them as shown in Figure 2. It indicates that when guanxi with team leaders is weak (−1 SD), promotive voice behavior tends to increase more steeply as psychological safety climate increases. The slope difference test also supported this positive relationship (t = 5.270, p < 0.001). However, when guanxi with a team leader was high, the relationship between the psychological safety climate and promotive voice behavior was not significant (t = 0.552, p = 0.581). Thus, Hypothesis 2a is supported.

Figure 2.

Moderating role of guanxi in the relationship between psychological safety and promotive voice behavior.

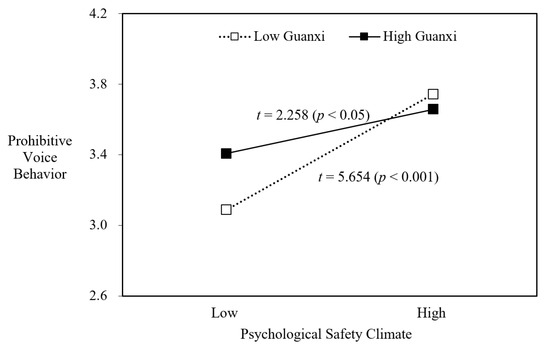

Finally, Hypothesis 2b states that guanxi with a team leader negatively moderates the relationship between psychological safety climate and prohibitive voice behavior. The result shows that the interaction term is statistically significant in a negative way (b = −0.198, p < 0.01). To interpret the results, we plotted them as shown in Figure 3. This indicates that when guanxi with a team leader is weak (−1 SD), prohibitive voice behavior tends to increase more steeply as the psychological safety climate increases. The slope difference test also supported this positive relationship (t = 5.654, p < 0.001). In addition, when guanxi with a team leader was high, the relationship between the psychological safety climate and prohibitive voice behavior was significant (t = 2.258, p < 0.05). Thus, Hypothesis 2b is supported.

Figure 3.

Moderating role of guanxi in the relationship between psychological safety and prohibitive voice behavior.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

This study investigated how psychological safety climate influences employee voice behavior—both promotive and prohibitive—and whether guanxi with a team leader moderates this relationship in the Chinese organizational context. The results provide empirical support for all proposed hypotheses, offering important theoretical and practical insights.

5.1.1. Psychological Safety Climate and Promotive Voice (H1a)

The results confirmed that psychological safety climate is positively associated with promotive voice behavior, supporting Hypothesis 1a. This finding aligns with previous research suggesting that when employees feel psychologically safe, they are more likely to propose constructive and future-oriented ideas aimed at improving organizational performance (e.g., [10]). In the Chinese context, despite its traditionally hierarchical and harmony-seeking cultural norms, a safe environment appears to empower employees to act proactively. This supports Hofstede’s cultural dimension theory, which indicates that China’s high long-term orientation fosters openness to change and innovation when risk is minimized [99,100,101].

5.1.2. Psychological Safety Climate and Prohibitive Voice (H1b)

Hypothesis 1b was also supported, demonstrating that psychological safety climate positively influences prohibitive voice behavior. This suggests that when employees perceive low interpersonal risk, they are more willing to speak out about problems, inefficiencies, or unethical practices. This finding is particularly notable in high power-distance cultures like China, where prohibitive voice can be socially risky. Consistent with previous studies [102,103], the result emphasizes the importance of institutional mechanisms—such as psychological safety—in enabling critical feedback.

5.1.3. Moderating Role of Guanxi with a Leader on Promotive Voice (H2a)

The moderating effect of guanxi on the relationship between psychological safety and promotive voice behavior was significant and negative, supporting Hypothesis 2a. Specifically, the positive impact of psychological safety climate on promotive voice was stronger when guanxi with the leader was weak. This finding implies that when employees lack strong personal ties with their leaders, they rely more on formal organizational climates for psychological assurance. This supports the resource substitution logic proposed by Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [116], in which the absence of one resource (guanxi) heightens the salience of another (psychological safety climate). It also reflects concerns raised in previous studies (e.g., [125]), which warn that overreliance on informal ties like guanxi may weaken formal performance feedback channels.

5.1.4. Moderating Role of Guanxi with a Leader on Prohibitive Voice (H2b)

Similarly, the moderating effect of guanxi was also significant in the case of prohibitive voice behavior, confirming Hypothesis 2b. When guanxi with a leader was low, psychological safety climate played a greater role in encouraging employees to raise critical concerns. This is consistent with findings from Nasir et al. [126], who noted that strong supervisor–subordinate relationships can reduce felt obligations to the broader organization, potentially discouraging the expression of dissenting views. In innovation-driven settings, where candid communication is essential for risk identification and mitigation, this highlights the risks of excessive dependence on interpersonal loyalty over institutional safety norms.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

The main contribution of this study is to explore whether and what type of association exists between psychological safety and voice behavior in technological innovation enterprises in the Chinese social context. In addition, this study explored and identified the role of guanxi with leaders.

5.2.1. Implications in the Context of Technological Innovation Enterprises

First, in the context of Chinese society, psychological safety was positively correlated with promotive voice behavior and prohibitive voice behavior. Employees are more willing to provide suggestions for improving work practices in the organization and contribute to the development and innovation of the organization when the degree of psychological safety is high. Simultaneously, employees are more willing to warn about the problems in the organization or factors that may damage the organization, with a high degree of psychological safety, to help the organization reduce losses and enhance development [2].

Previous research on voice behavior has predominantly focused on stable industry environments such as traditional manufacturing or service sectors, with relatively limited exploration in the realm of technological innovation enterprises characterized by high uncertainty and rapid change [4]. Technology innovation companies operate in an environment marked by swift technological iteration, intense market competition, and immense innovation pressure, where employee voice behavior is crucially important for sustaining innovation and corporate growth [12]. This study, through empirical analysis of the relationship between psychological safety climate and voice behavior, offers fresh perspectives and theoretical underpinnings for applying voice behavior theory in the context of technology innovation enterprises. It thereby contributes to advancing the theoretical framework of voice behavior, enhancing its adaptability to diverse industry contexts.

5.2.2. Recontextualizing Psychological Safety in Technological Innovation Enterprises

Second, psychological safety climate is a crucial concept in organizational behavior research. Previous studies have primarily examined its impact on employee communication, learning behavior, and work performance [7,45]. This research connects psychological safety climate with voice behavior, with a particular focus on its mechanisms of influence within Chinese technology innovation enterprises. Employees in technology innovation companies typically possess advanced knowledge and professional skills, and their perception of psychological safety in the workplace may differ from that of employees in traditional enterprises [44]. By investigating the relationship between psychological safety climate and voice behavior, this study expands the boundaries of psychological safety climate theory. It uncovers the complex mechanisms through which this climate affects employee behavior in diverse work contexts, thereby opening new avenues for the development of psychological safety climate theory.

5.2.3. Guanxi as a Moderator in the Psychological Safety–Voice Behavior Link

Third, guanxi with team leaders has consistently served as a significant moderating variable in organizational behavior research [51], yet its moderating role in the relationship between psychological safety climate and voice behavior remains underexplored. Our study contributes to the growing body of literature on guanxi in the Chinese organizational context by offering a complementary perspective to that of Nasir et al. [126], who demonstrated that supervisor–subordinate guanxi enhances employees’ knowledge-sharing and innovative work behaviors through a mediating mechanism of felt obligation. While their findings highlight the motivational function of guanxi in promoting positive employee outcomes, our study uncovers a substitutive role of guanxi, showing that strong guanxi with a team leader may reduce the reliance on formal psychological safety climate as a driver of voice behavior. These findings contribute to deepening our understanding of the moderating effects of guanxi with a team leader in the realm of employee psychology and behavior. Within Chinese technology innovation enterprises, guanxi with team leaders is often shaped by diverse factors including cultural norms, organizational structures, and job characteristics. Through empirical investigation, this research uncovers specific patterns of this moderating effect, thereby offering novel insights for applying team leadership theory in complex organizational contexts.

5.3. Practical Implications

5.3.1. Enhancing Innovation Through a Psychological Safety Climate

First, psychological safety climate serves as a critical factor influencing employee voice behavior, which is essential for innovation and development in technology-driven enterprises. This research demonstrates that fostering a positive psychological safety climate can effectively promote employee voice behavior within such organizations. For instance, companies may enhance this climate by establishing open communication channels and encouraging expression of diverse opinions and suggestions. Such measures stimulate innovative thinking among employees, increasing their willingness to propose ideas for technological innovation, product enhancement, and management optimization. Consequently, this cultivates a dynamic and proactive innovation ecosystem, driving sustained organizational innovation and competitive advantage.

5.3.2. Managing Voice Behavior Through Guanxi and Leadership Interventions

Second, the study’s findings on the moderating role of guanxi with a team leader in psychological safety climate–voice behavior provide practical guidance for managing teams in technology innovation enterprises. Notably, when guanxi with a team leader is weaker, the association between psychological safety climate and voice behavior becomes stronger. This suggests that organizations should prioritize the creation of a psychologically safe climate to compensate for leadership deficits when guanxi with the team leader is weakly cohesive. One specific approach is improving work environments, strengthening interpersonal trust among employees. Concurrently, enterprises may enhance leadership relations through conducting team-building activities, developing leaders’ communication competencies, and strengthening leadership capabilities. These interventions help channel employee voice behavior toward organizational innovation goals, thereby optimizing team management while elevating collective innovative capacity and execution capabilities.

5.3.3. Implications for Talent Attraction and Organizational Commitment

Finally, in today’s fiercely competitive market, talent constitutes the core competitive advantage for technology innovation enterprises. A positive psychological safety climate and proactive voice culture can attract and retain exceptional professionals. When employees perceive that their opinions are valued and can express ideas freely within a secure environment, they develop stronger organizational commitment and loyalty. Our findings enable technology-driven enterprises to recognize that optimizing psychological safety climate and managing team leadership relations creates an environment conducive to talent development. Moreover, our results align with Yahiaoui et al. [127], who highlight the double-edged nature of informal, network-based HRM—bringing both benefits and risks. Similarly, Wang et al. [128] demonstrate that workplace friendship also functions as a mixed blessing: under low competitive climates, it enhances psychological safety and promotes voice, whereas under highly competitive climates, it increases face concern and inhibits voice. These findings, along with ours, suggest that informal relational mechanisms such as guanxi and workplace friendship require careful contextual management, as their effects on employee behavior vary depending on surrounding organizational climates. Overreliance on guanxi may undermine formal mechanisms such as psychological safety climate, potentially limiting open communication and inclusive decision-making [125]. Thus, organizations should adopt a strategic approach that integrates the advantages of guanxi while reinforcing institutional structures that promote psychological safety. This balanced strategy not only enhances employee voice but also strengthens the organization’s position in the competition for top-tier talent, securing a robust foundation for long-term innovation and sustainability.

5.4. Future Research and Limitations

This study helps validate the effects of guanxi on the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior; however, it has some limitations. First, it explored the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior among private manufacturing enterprises in China. Because of regional and cultural differences, it is important to conduct an empirical analysis of organization members from different countries and cultures to obtain the same results. Thus, it is necessary to conduct similar explorations of manufacturing firms in other countries and compare them with the results of this study.

Second, this study used a self-report survey method and corresponding scales to investigate the variables and analyze the consequences from the perspective of employees. In future studies, a measurement scale for leader–employee mutual evaluation could be used, and more objective data could be obtained using organizational- and individual-level reports [129]. Therefore, future studies could use cross-level research methods to explore the relationship between psychological safety and voice behavior.

Third, while this study provides insights into the relationship between safety climate and employee voice behavior, it does not explicitly account for the role of organizational culture as a potential mediating or moderating variable. Prior research, such as Joseph and Shetty [130], has demonstrated that organizational culture significantly influences the dynamics between psychological safety and employee voice or silence. Their findings suggest that employees’ perception of cultural norms within an organization can either encourage open communication or lead to suppression of ideas due to fear of negative consequences. Future research should empirically examine the interplay between safety climate and organizational culture to provide a more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms that drive voice behavior in the workplace.

Finally, cross-sectional data were used in this study, and future research could use longitudinal research to collect data over time to observe differences in changes and effects.

Author Contributions

C.O.: writing—original draft preparation, methodology and formal analysis, investigation, M.C.: conceptualization, writing—original draft preparation, supervision and methodology, H.E.K.: writing—review and editing, software, resources, methodology. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by 2022 Research Grant from Kangwon National University. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2022S1A5A2A01049890).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Survey studies in business administration are exempt from review and approval in Gachon Univ. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to university policy.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Items measuring psychological safety climate:

- If you make a mistake on this team, it is often held against you.

- Members of this team are able to bring up problems and tough issues.

- People on this team sometimes reject others for being different.

- It is safe to take a risk on this team.

- It is difficult to ask other members of this team for help.

- No one on this team would deliberately act in a way that undermines my efforts.

- Working with members of this team, my unique skills and talents are valued and utilized.

Items measuring promotive voice behaviors:

- I proactively suggest new approaches that are beneficial to the change implementation processes.

- I raise suggestions to improve the change implementation processes.

- I proactively voice out constructive suggestions that improve the change implementation processes.

- I make constructive suggestions to improve the change implementation processes.

- I proactively develop and make suggestions for issues that may influence the change implementation processes.

Items measuring prohibitive voice behaviors:

- I dare to point out problems in the change implementation processes when they appear, even if that will hamper relationships with other colleagues.

- I speak up honestly with problems in the change implementation processes that may cause serious loss to the organization, even when/though dissenting opinions exist.

- I proactively report coordination problems in the change implementation processes to the management.

- I dare to voice out opinions on things that may affect efficiency of the change implementation processes in the organization, even if that will embarrass others.

- I advise others against the undesirable change implementation processes that will hamper the change implementation.

Items measuring guanxi with team leaders:

- During holidays or after office hours, I would call my supervisor or visit him/her.

- My supervisor invites me to his/her home for lunch or dinner.

- On special occasions such as my supervisor’s birthday, I would definitely visit my supervisor and send him/her gifts.

- I always actively share with my supervisor about my thoughts, problems, needs and feelings.

- I care about and have a good understanding of my supervisor’s family and work conditions.

Items measuring leader–member exchange (LMX):

- I like my supervisor very much as a person.

- My supervisor is the kind of person one would like to have as a friend.

- My supervisor is a lot of fun to work with.

- My supervisor defends my work actions to a superior, even without complete knowledge of the issue in question.

- My supervisor would come to my defense if I were ‘attacked’ by others.

- My supervisor would defend me to others in the organization if I made an honest mistake.

- I do work for my supervisor that goes beyond what is specified in my job description.

- I am willing to apply extra efforts, beyond those normally required, to further the interests of my work group.

- I am impressed with my supervisor’s knowledge of his/her job.

- I respect my supervisor’s knowledge of and competence on the job.

- I admire my supervisor’s professional skills.

References

- Shen, Z.; Siraj, A.; Jiang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, J. Chinese-style innovation and its international repercussions in the new economic times. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, R.; Lu, L.; Cao, Y.; Du, Q. The high-performance work system, employee voice, and innovative behavior: The moderating role of psychological safety. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Cao, C. Planning for science: China’s “grand experiment” and global implications. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2021, 8, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrah, O. Do we need friendship in the workplace? The effect on innovative behavior and mediating role of psychological safety. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 28597–28610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.A.; Di Fabio, A. Psychology of sustainability and sustainable development in organizations: Empirical evidence from environment to safety to innovation and future research. In Psychology of Sustainability and Sustainable Development in Organizations; Routledge: London, UK, 2023; pp. 20–41. [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard, I.M.; Edmondson, A.C. Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2006, 27, 941–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.; Donohue, R.; Eva, N. Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2017, 27, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Bohmer, R.M.; Pisano, G.P. Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 685–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Kramer, R.M.; Cook, K.S. Psychological safety, trust, and learning in organizations: A group-level lens. Trust Distrust Organ. Dilemmas Approaches 2004, 12, 239–272. [Google Scholar]

- Detert, J.R.; Burris, E.R. Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W. Employee voice behavior: Integration and directions for future research. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2011, 5, 373–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipton, H.; Kougiannou, N.; Do, H.; Minbashian, A.; Pautz, N.; King, D. Organisational voice and employee-focused voice: Two distinct voice forms and their effects on burnout and innovative behavior. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2024, 34, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LePine, J.A.; Van Dyne, L. Voice and cooperative behavior as contrasting forms of contextual performance: Evidence of differential relationships with big five personality characteristics and cognitive ability. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.H.; Rim, H. Employees’ voice behavior in response to corporate social irresponsibility (CSI): The role of organizational identification, issue perceptions, and power distance culture. Public Relat. Rev. 2023, 49, 102366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsetouhi, A.M.; Mohamed Elbaz, A.; Soliman, M. Participative leadership and its impact on employee innovative behavior through employee voice in tourism SMEs: The moderating role of job autonomy. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2023, 23, 406–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, M.C.D.; Schlosser, F.; McPhee, D. Building organizational innovation through HRM, employee voice and engagement. Pers. Rev. 2021, 50, 751–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, C.J.; Staw, B.M. The tradeoffs of social control and innovation in groups and organizations. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989; Volume 22, pp. 175–210. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dyne, L.; LePine, J.A. Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Acad. Manag. J. 1998, 41, 108–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Van de Vliert, E.; Van der Vegt, G. Breaking the Silence Culture: Stimulation of Participation andEmployee Opinion Withholding Cross-nationally. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2005, 1, 459–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, D.R.; Quiñones, M.A. Disentangling the effects of voice: The incremental roles of opportunity, behavior, and instrumentality in predicting procedural fairness. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002, 87, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brinsfield, C.T. Employee voice and silence in organizational behavior. In Handbook of Research on Employee Voice; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2014; pp. 114–132. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.J.; Li, F.; Chen, T.; Crant, J.M. Proactive personality and promotability: Mediating roles of promotive and prohibitive voice and moderating roles of organizational politics and leader-member exchange. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 145, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejaz, T.; Anjum, Z.U.Z.; Rasheed, M.; Waqas, M.; Hameed, A.A. Impact of ethical leadership on employee well-being: The mediating role of job satisfaction and employee voice. Middle East J. Manag. 2022, 9, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayfield, J.; Mayfield, M.; Nguyen, C.N. Raise their voices: The link between motivating language and employee voice. Int. J. Strateg. Commun. 2024, 18, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lam, L.W.; Zhang, L.L. The curvilinear relationship between job satisfaction and employee voice: Speaking up for the organization and the self. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2020, 37, 587–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Geng, Z.; Wang, Y. Linking leader–member exchange to employee voice behavior: The mediating role of self-efficacy. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2021, 49, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.L.; Diefendorff, J.M.; Kim, T.Y.; Bian, L. Personality and participative climate: Antecedents of distinct voice behaviors. Hum. Perform. 2014, 27, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walumbwa, F.O.; Schaubroeck, J. Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. J. Appl. Psychol. 2009, 94, 1275–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arshad, F.; Saleem, H. Examining the impact of spiritual leadership on employee’s intrapreneurial behavior: The moderating role of perceived organizational support and mediating role of psychological safety. J. Workplace Behav. 2024, 5, 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Dahinten, V.S. Psychological safety as a mediator of the relationship between inclusive leadership and nurse voice behaviors and error reporting. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2021, 53, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, E.H.; Bennis, W.G. Personal and Organizational Change Through Group Methods: The Laboratory Approach; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Omari, M.; Sharafizad, F. Inclusive leadership and workplace bullying: A model of psychological safety, self-esteem, and embeddedness. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2024, 31, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Higgins, M.; Singer, S.; Weiner, J. Understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: A comparative perspective. Res. Hum. Dev. 2016, 13, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltokorpi, V. Transactive memory directories in small work units. Pers. Rev. 2004, 33, 446–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kızrak, M.; Çınar, E.; Aydın, E.; Kemikkıran, N. How 37. eave? The mediation roles of networking ability and relational job crafting. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 9485–9503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Gnyawali, D.R. Developing synergistic knowledge in student groups. J. High. J. High. Educ. 2003, 74, 689–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Wei, K.K.; Chen, H. Exploring the role of psychological safety in promoting the intention to continue sharing knowledge in virtual communities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2010, 30, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Yang, Y. Student learning in business simulation: An empirical investigation. J. Educ. Bus. 2010, 85, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A.; Gittell, J.H. High-quality relationships, psychological safety, and learning from failures in work organizations. J. Organ. Behav. Int. J. Ind. Occup. Organ. Psychol. Behav. 2009, 30, 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanner, B.; Bunderson, J.S. Psychological safety, learning, and performance: A comparison of direct and contingent effects. Acad. Manag. Proc. 2013, 2013, 10198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienefeld, N.; Grote, G. Speaking up in ad hoc multiteam systems: Individual-level effects of psychological safety, status, and leadership within and across teams. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2014, 23, 930–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Seo, J.K.; Squires, A. Voice, silence, perceived impact, psychological safety, and burnout among nurses: A structural equation modeling analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2024, 151, 104669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Appelbaum, N.P.; Dow, A.; Mazmanian, P.E.; Jundt, D.K.; Appelbaum, E.N. The effects of power, leadership and psychological safety on resident event reporting. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C. The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and Growth; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.P.; Pearsall, M.J. Reducing the negative effects of stress in teams through cross-training: A job demands-resources model. Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 2011, 15, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Lei, Z. Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2014, 1, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, R.; McAuliffe, E. A systematic review exploring the content and outcomes of interventions to improve psychological safety, speaking up and voice behaviour. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y. Psychological safety, employee voice, and work engagement. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2020, 48, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Loretta Kim, S.; Yun, S. Encouraging employee voice: Coworker knowledge sharing, psychological safety, and promotion focus. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 34, 1044–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung Chou, S.; Han, B.; Zhang, X. Effect of guanxi on Chinese subordinates’ work behaviors: A conceptual framework. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2014, 6, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.Y.F.; Tjosvold, D. Guanxi and leader member relationships between American managers and Chinese employees: Open-minded dialogue as mediator. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2007, 24, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, M. Guanxi and its role in business. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2007, 1, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.H. Cultural and organizational antecedents of guanxi: The Chinese cases. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 99, 441–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Chen, C.C. Chinese guanxi: The good, the bad and the controversial. In Handbook of Chinese Organizational Behavior; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A. Mapping out the interpersonal boundary stones in contemporary China: Guanxi network structure and its association with traditional culture endorsement. Br. J. Sociol. 2024, 75, 588–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Khan, H.S.U.D.; Chughtai, M.S.; Li, M.; Ge, B.; Qadri, S.U. A review of supervisor–subordinate guanxi: Current trends and future research. Sustainability 2023, 15, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.T.; Ngo, H.Y.; Wong, C.S. Antecedents and outcomes of employees’ trust in Chinese joint ventures. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2003, 20, 481–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Lin-Schilstra, L.; Yang, C.; Fan, X. Does participation generate creativity? A dual-mechanism of creative self-efficacy and supervisor-subordinate guanxi. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2021, 30, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.P.; Chen, C.C. On the intricacies of the Chinese guanxi: A process model of guanxi development. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2004, 21, 305–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farh, J.L.; Tsui, A.S.; Xin, K.; Cheng, B.S. The influence of relational demography and guanxi: The Chinese case. Organ. Sci. 1998, 9, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, A.S.; Farh, J.L.; Xin, K.R. Guanxi in the Chinese context. In Management and Organizations in the Chinese Context; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2000; pp. 225–244. [Google Scholar]

- Karikumpu, V.; Häggman-Laitila, A.; Romppanen, J.; Kangasniemi, M.; Terkamo-Moisio, A. Trust in the leader and trust in the organization in healthcare: A concept analysis based on a systematic review. J. Nurs. Manag. 2024, 2024, 8776286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; An, R.; Hewlin, P.F. Paternalistic leadership and employee well-being: A moderated mediation model. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2019, 13, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, K.S.; Wong, C.S.; Wang, D.; Wang, L. Effect of supervisor–subordinate guanxi on supervisory decisions in China: An empirical investigation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2000, 11, 751–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wu, W.; Hao, S.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. On-work or off-work relationship? An engagement model of how and when leader–member exchange and leader–member guanxi promote voice behavior. Chin. Manag. Stud. 2017, 11, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, J.; Zhang, J. The relationship between person–team fit with supervisor–subordinate guanxi and organizational justice in a Chinese state-owned enterprise. Int. J. Sel. Assess. 2019, 27, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, W.; Sun, G.; Jiang, Z.; Cheng, Z. Supervisor–subordinate guanxi and job satisfaction among migrant workers in China. Soc. Indic. Res. 2018, 139, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, C.; Qian, S.; Banks, G.C.; Seers, A. Supervisor-subordinate guanxi: A meta-analytic review and future research agenda. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, H. How supervisor–subordinate guanxi influence employee innovative behavior: A moderated mediation model. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 2001–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, P. Supervisor-subordinate Guanxi and employee voice behavior: Trust in supervisor as a mediator. Soc. Behav. Personal. Int. J. 2018, 46, 1169–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Z.; Lee, J.; Xu, F. Achieving sustainable development in China: A moderated mediation model of guanxi HRM practices. Front. Psychol. 2025, 16, 1620530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, F.; Peng, J. How does authentic leadership influence employee voice? From the perspective of the theory of planned behavior. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 1851–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Liang, Q.; Feng, C.; Zhang, Y. Leadership and follower voice: The role of inclusive leadership and group faultlines in promoting collective voice behavior. J. Appl. Behav. Sci. 2023, 59, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Kim, B.J.; Lee, J. The effect of job insecurity on knowledge hiding behavior: The mediation of psychological safety and the moderation of servant leadership. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1108881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Qing, C.; Jin, S. Ethical leadership and innovative behavior: Mediating role of voice behavior and moderated mediation role of psychological safety. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Dollard, M.F.; Taris, T.W. Organizational context matters: Psychosocial safety climate as a precursor to team and individual motivational functioning. Saf. Sci. 2022, 145, 105524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetto, Y.; Saheli, N.; Dick, T.; Nelson, S. Psychosocial safety climate, psychological capital, healthcare SLBs’ wellbeing and innovative behaviour during the COVID 19 pandemic. Public Perform. Manag. Rev. 2022, 45, 751–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrigino, M.B.; Chen, H.; Dunford, B.B.; Pratt, B.R. If we see, will we agree? Unpacking the complex relationship between stimuli and team climate strength. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2021, 15, 151–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussin, C.J.; MacLean, T.L.; Rudolph, J.W. The safety in unsafe teams: A multilevel approach to team psychological safety. J. Manag. 2016, 42, 1409–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C. Managing the risk of learning: Psychological safety in work teams. In International Handbook of Organizational Teamwork and Cooperative Working; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Fyhn, B.; Bang, H.; Egeland, T.; Schei, V. Safe among the unsafe: Psychological safety climate strength matters for team performance. Small Group Res. 2023, 54, 439–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C.; Bransby, D.P. Psychological safety comes of age: Observed themes in an established literature. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 55–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guchait, P.; Paşamehmetoğlu, A. Tolerating errors in hospitality organizations: Relationships with learning behavior, error reporting and service recovery performance. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2635–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazier, M.L.; Tupper, C. Supervisor prosocial motivation, employee thriving, and helping behavior: A trickle-down model of psychological safety. Group Organ. Manag. 2018, 43, 561–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koopmann, J.; Lanaj, K.; Wang, M.; Zhou, L.; Shi, J. Nonlinear effects of team tenure on team psychological safety climate and climate strength: Implications for average team member performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauwelier, P.; Ribiere, V.M.; Bennet, A. The influence of team psychological safety on team knowledge creation: A study with French and American engineering teams. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1157–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.; Tjosvold, D.; Lu, J. Leadership values and learning in China: The mediating role of psychological safety. Asia Pac. J. Hum. Resour. 2010, 48, 86–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröster, C.; Van Knippenberg, D. Leader openness, nationality dissimilarity, and voice in multinational management teams. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2012, 43, 591–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espedido, A.; Searle, B.J. Proactivity, stress appraisals, and problem-solving: A cross-level moderated mediation model. Work Stress 2021, 35, 132–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahn, W.A. Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 692–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Stobbeleir, K.; Ashford, S.; Zhang, C. Shifting focus: Antecedents and outcomes of proactive feedback seeking from peers. Hum. Relat. 2020, 73, 303–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, K.R.; Ghani, B. The relationship between performance appraisal system and employees’ voice behavior through the mediation-moderation mechanism. South Asian J. Bus. Stud. 2023, 12, 220–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Ding, W.; Wang, R.; Li, S. Inclusive leadership and employees’ voice behavior: A moderated mediation model. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 41, 6395–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, A.K.; Ravlin, E.C.; Klaas, B.S.; Ployhart, R.E.; Buchan, N.R. When do high-context communicators speak up? Exploring contextual communication orientation and employee voice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2016, 101, 1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Mao, J.Y.; Chiang, J.T.J.; Guo, L.; Zhang, S. When and why does voice sustain or stop? The roles of leader behaviours, power differential perception and psychological safety. Appl. Psychol. 2023, 72, 1209–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, D.; Zierler, B. Clinical nurses’ experiences and perceptions after the implementation of an interprofessional team intervention: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2019, 28, 430–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, E.W.; Wheeler-Smith, S.L.; Kamdar, D. Speaking up in groups: A cross-level study of group voice climate and voice. J. Appl. Psychol. 2011, 96, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Bond, M.H. Hofstede’s culture dimensions: An independent validation using Rokeach’s value survey. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1984, 15, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, G.S.; McIntosh, C.K.; Salazar, M.; Vaziri, H. Cultural values and definitions of career success. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2020, 30, 392–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Álvarez, I.; Pucheta-Martínez, M.C. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and R&D intensity as an innovation strategy: A view from different institutional contexts. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2021, 11, 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, S.; Burke, M.; Chen, H.; Tan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Hou, L. Mitigating the psychologically detrimental effects of supervisor undermining: Joint effects of voice and political skill. Hum. Relat. 2022, 75, 87–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Ge, X.; Wang, P. Supervisor-subordinate guanxi and innovative behavior: The roles of psychological ownership and emotional uncertainty. Curr. Psychol. 2024, 43, 9877–9888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]