1. Introduction

Over the past decade, the gravitational pull of globalization has not only redrawn competitive boundaries but also redrafted the criteria by which consumers judge brands. Visibility and sheer market reach—once the lodestars of global brand strategy [

1]—no longer guarantee goodwill. Today’s buyers, armed with an acute awareness of ecological and social fragility, sift brands through an ethical lens and favor those that weave sustainability into their DNA [

2,

3]. For multinational firms, this shift raises the stakes: Trust and loyalty must now be earned through demonstrable, measurable responsibility rather than rhetoric [

4,

5].

Against this backdrop, PBG has taken on new meaning. A logo recognized on every continent is helpful only if, as consumers increasingly demand, it also signals credible commitments to the planet and its people. Many firms have responded by foregrounding robust corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs, hoping to translate ethical pedigree into higher perceived quality and more substantial brand equity [

6,

7,

8,

9]. However, the past four years have shown that even well-established global marques are far from invulnerable [

10]. Pandemic-driven supply-chain ruptures cascaded into inflationary pressure, prompting households to tighten spending and re-evaluate their brand repertoire through a pragmatic, risk-averse lens.

Furthermore, as countries have been forced to confront the reality of scarce resources, they have adopted more sustainable policies and development goals to enhance the efficient use of resources [

11,

12,

13]. Additionally, technological advancements have increased consumers’ access to information, and developments in advertising technologies have heightened the global visibility of brands, fostering more substantial consumer expectations for social and environmental responsibility. The growing awareness of environmental sustainability has led consumers to scrutinize brands’ environmental impact more closely and respond negatively to brands that fail to demonstrate responsibility in this regard [

14]. Brands have moved away from mere token promises of sustainability to set genuine long-term sustainability goals, raising consumer awareness, and building trust. Otherwise, brands are aware that consumers will boycott those that engage in environmentally harmful practices, creating pressure for these brands to comply with sustainability principles.

Since 2021, global conflicts have further driven consumers toward more conscious and sustainable consumption habits. These conflicts have significantly increased food prices, leaving millions worldwide facing food insecurity and negatively impacting agricultural production and supply chains [

15]. With approximately 1.7 billion people suffering from hunger, awareness of food sources and security has grown, leading to an increased demand for local and sustainable food options [

16]. Disruptions in global supply chains have also fueled demand for local production, with consumers opting for locally produced goods to reduce dependence on external sources and ensure economic stability [

17]. This trend has led to a decline in the sales of global brands while local producers have increased their market share.

Environmental and humanitarian crises caused by conflicts have heightened consumers’ awareness of social responsibility, driving demand for ethical and sustainable brands. Ethnocentric consumers tend to trust domestically produced brands more, perceiving their sustainability efforts as superior and supporting them as a national duty [

18]. This creates an advantage for local brands while highlighting the need for global brands to align with local values. Strengthening the connection between brand globalness and sustainability perceptions can positively influence PIs.

Global brands increasingly focus on sustainability-driven marketing strategies, especially in developing countries [

19]. These efforts aim to fulfill environmental and social responsibilities while enhancing perceptions of ethicality and trustworthiness. Notably, 24% of consumers in developing countries actively seek sustainable products, a figure that is rapidly growing [

20]. This trend pressures global brands to adopt more comprehensive sustainability practices. However, the success of these strategies depends on the consistency and credibility of consumers’ perceptions regarding brand globalness and social responsibility efforts. In developing markets, perceived alignment between a brand’s sustainability practices and consumer expectations plays a critical role in shaping PIs.

The primary aim of this study is to thoroughly examine the impact of PBG on SPIs between 2021 and 2024. The mediating effects of PBQ, PBP, and BCF in the relationship between PBG and SPIs are explored in this context. Although previous research suggests that the level of CE in developing countries is generally low [

21,

22], this study demonstrates how economic and political events between 2021 and 2024 have strengthened ethnocentric perceptions in these countries, leading to a greater preference for domestic brands. In this context, the need for global brands to more closely align with local values is discussed, and the potential for creating a stronger connection between consumers’ sustainability perceptions and brand globalness is examined. Accordingly, this study addresses the following research questions:

How does PBG influence SPI between 2021 and 2024?

Through which mechanisms—PBQ, PBP, and BCF—does PBG affect SPI, and do these mediating effects change over time?

To what extent does CE moderate the relationships among PBG, PBQ, PBP, BCF, and SPI, and how does this moderating role evolve from 2021 to 2024?

What is the comparative explanatory and predictive power of these constructs across the two waves in an emerging-market context?

Although Turkey offers a theoretically informative emerging-market setting (post-pandemic volatility, inflation, supply-chain shocks), we treat it as an analytical exemplar rather than a universal proxy; hence, we refrain from overgeneralizing beyond comparable contexts and call for cross-national replication.

This study makes four main theoretical contributions. First, it provides the first longitudinal evidence on how the PBG–SPI nexus and its mediators (PBQ, PBP, BCF) are time-variant in an emerging market, cautioning against single-wave generalizations. Second, it demonstrates a post-pandemic decoupling of prestige from sustainable purchase behavior, refining sustainability marketing theory by highlighting the ascendancy of substantive (quality, cause-fit) over symbolic (prestige) cues. Third, it challenges the prevailing assumption that consumer ethnocentrism is muted in developing economies, documenting its sharp rise and its reconfiguring role as a negative moderator of globalness and prestige but a positive amplifier of quality and cause-alignment. Fourth, methodologically, it showcases how moderated mediation can be modeled longitudinally with PLS-SEM, offering a template for future research on dynamic brand–consumer relationships.

To maintain coherence and facilitate comprehension, we organize our contributions in a systematic manner. The theoretical implications are articulated in this introduction and examined in greater depth in

Section 5, whereas the practical implications are integrated under the subheading “Managerial Implications” in

Section 7. The structure of the paper is as follows:

Section 2 develops the literature review and formulates the hypotheses,

Section 3 outlines the research methodology,

Section 4 reports the empirical findings,

Section 5 elaborates on the theoretical contributions, and

Section 6 addresses the study’s limitations and avenues for future research.

2. Literature Review and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Markets for branded goods are characterized by information asymmetries, as consumers rarely observe production processes, sustainability practices, or long-term quality in advance. In such contexts, signaling (cue-utilization) theory argues that actors rely on observable proxies to infer unobservable attributes [

23]. PBG is one such proxy. A brand’s worldwide presence is read as evidence of coordination capability, stringent quality control, and institutional legitimacy, allowing consumers to collapse complex uncertainty into tractable judgments of PBQ, PBP, and BCF [

1]. In other words, globalness is not valued per se but functions epistemically as a signal—its meaning is decoded through the lenses of quality assurance, status relevance, and ethical congruence. This signal logic is especially salient in emerging markets, where formal certification regimes may be weaker and consumers lean more heavily on brand-level heuristics. If signaling theory clarifies how consumers move from globalness to evaluative inferences, attribution theory [

24,

25] clarifies why those inferences translate—or fail to translate—into behavioral intentions. Consumers do not passively accept corporate responsibility claims; they interrogate motive and fit. BCF captures this attributional calculus: when a brand’s sustainability initiative appears congruent with its core identity, consumers infer intrinsic, value-driven motives and suspend skepticism; when congruence is low, they impute opportunism and discount the claim [

26]. Thus, ethical credibility is not a simple extension of global visibility; it is earned through perceived integrity of motive and schema congruity. PBG can facilitate this process only insofar as global reach is interpreted as the capacity to act responsibly, not merely to communicate broadly.

A third lens, social identity theory [

27] and its marketing instantiation in CE, explains how national identity concerns filter and reweigh brand cues. CE embodies a moral–economic stance that privileges domestic welfare and casts foreign/global symbols as potential threats to local jobs, culture, or sovereignty [

21]. Consequently, identity-laden consumers do not uniformly reject global brands; they selectively valorize signals that align with in-group obligations (e.g., demonstrable local benefit, transparent quality, cause alignment) and devalue those that connote cosmopolitan elitism or external dominance (e.g., prestige untethered to national value) [

18]. CE, in this view, is a contextual moderator rather than a background trait—its salience waxes and wanes with macro events and institutional cues.

Finally, a temporal/process perspective is required to integrate these theories within a post-pandemic, turbulence-ridden environment. Signaling value, attributional judgments, and identity boundaries are not static parameters; they are historically contingent, path-dependent processes that respond to inflationary shocks, supply chain ruptures, regulatory tightening, and geopolitical conflict. The 2021–2024 window illustrates how the diagnosticity of symbolic versus substantive cues can shift: prestige retains conceptual coherence but loses motivational force, while quality and cause fit remain resilient anchors of ethical evaluation; CE intensifies and reorders which cues are legitimate. A longitudinal design is, therefore, not a methodological luxury, but a theoretical necessity for observing how mechanisms evolve rather than assuming cross-sectional stability.

Against this theoretical backdrop, it is helpful to situate SPI within its broader nomological network. Prior research documents the multi-level antecedents of SPI, including individual values (environmental concern, moral norms, perceived consumer effectiveness), brand-level cues (PBQ, trust, PBP, BCF), and contextual forces (price sensitivity, availability, regulation, and macroeconomic uncertainty). Social influence (subjective norms, peer signals) and transparency instruments (eco-labels, third-party audits) further calibrate whether pro-sustainability attitudes convert into action. Within this constellation, our model deliberately foregrounds PBQ, PBP, BCF, and CE because they are the conceptual conduits through which PBG is interpreted, and because a longitudinal lens allows us to track how their explanatory power shifts as the macro-environment changes.

2.2. Perceived Brand Globalness

The prevailing trend in evaluating global brands from a consumer perspective defines these brands by adopting standard communication and marketing strategies, and having a presence in more than one country [

28]. The concept of PBG, introduced by Steenkamp et al. [

1], refers to consumers’ belief that a brand is globally marketed and recognized. When consumers perceive a brand as widely known and accepted worldwide, it is considered to have high PBG, and their trust in the brand is developed, and PI is affected [

1].

The relationship between PBG and SPI is affected by factors such as consumers’ exposure to global brands, brand perception, trust, quality, and reliability. According to Erdem et al. [

28], when the attributes of a product are unclear, costs are high, and products are not readily available, consumers rely on these signals to evaluate quality. In this context, PBG serves as an essential quality signal. Consistent with signaling theory [

23], PBG serves as an extrinsic cue under information asymmetry, prompting consumers to infer a brand’s quality, legitimacy, and ethical commitment—judgments that subsequently shape their sustainable purchase intentions.

However, various factors influence consumers’ intentions when choosing a product, and the final decision depends on both consumer intentions and external factors. Vuong and Giao [

29] argue that marketers view consumers’ positive attitudes and perceptions toward a product as crucial indicators of its ability to attract them. In this context, SPI related to global brands generally reflects consumers’ interest and preferences for that brand. When consumers view a brand as global, they tend to associate it with greater value. Research supports a significant correlation between PBG and consumer behavior [

29,

30,

31]. Pyun et al. [

32] found that the PBG of the English Premier League, as perceived by South Korean viewers, positively influenced viewing intentions. Similarly, Baek et al. [

30] demonstrated that high PBG enhanced trust in a brand’s sustainability efforts, positively impacting SPI. Hatzithomas et al. [

33] emphasized the growing consumer demand for global brands to implement sustainability initiatives, underscoring the role of sustainability in fostering loyalty. Integrating sustainability into brand strategies aligns with consumer values, further driving SPI.

H1. PBG positively affects consumers’ SPI.

2.3. Perceived Brand Quality

PBQ refers to a subjective evaluation of a product that does not always correspond to its objective or actual quality [

34]. This evaluation encompasses intangible factors such as abstract impressions and brand associations, directly influences individuals’ perceptions of the overall value of a product, and emerges as one of the most influential factors shaping consumer brand preferences [

1,

35]. Consistent with signaling theory [

27], consumers treat PBG as a heuristic for otherwise unobservable performance attributes, so higher perceived globalness elevates expectations of quality.

Consumers tend to associate global brands with superior quality [

36], and the perception of a brand’s global presence is closely linked to its associated superior quality. Global brands are often positioned at higher price points, a factor that is perceived by consumers as an indicator of superior quality. Such brands’ advertising strategies often emphasize quality and highlight their products’ superior features. However, consumers prefer global brands of Western origin over local brands [

37]. This trend is particularly evident among consumers in developing countries, who associate standardized, globally distributed, and universally recognized brands with superior quality [

29]. As a result, consumers in these markets show stronger loyalty to foreign brands due to PBQ; in underdeveloped markets, there is a positive relationship between PBG and PBQ [

38,

39]. In addition, a study on brand loyalty revealed that consumers who prefer local brands attach more importance to product experience, while those who prefer global brands prioritize PBQ [

40]. The direct effect of PBG in increasing PBQ suggests that when consumers perceive a brand’s global presence, their quality expectations for the brand also increase [

40].

H2. PBG positively affects consumers’ PBQ.

PBQ is a key driver of consumer trust and PIs, with global brands often perceived as higher-quality [

41]. Consistent with signaling and expectancy–value perspectives, higher perceived quality reduces perceived risk and elevates the utilitarian value of choosing a sustainable option, thereby translating directly into stronger SPI. This perception goes beyond the product itself to include a brand’s environmental and social responsibilities, making PBQ central to sustainable marketing strategies [

4,

42]. When consumers believe a brand meets these responsibilities, they show greater preference and likelihood of repurchase. In sportswear, perceived sustainability notably increases PIs, especially for reputable brands [

43]. A brand’s sustainability also reflects technical innovation, environmental stability, and safety, boosting trust in its commitments [

44]. Many consumers opt for global brands due to perceived quality, even where sustainability awareness is limited. Moreover, higher perceived quality correlates with positive environmental attitudes and stronger purchase behavior [

45]. Thus, a global brand’s socially responsible marketing strategy can significantly influence sustainable purchases, as its global presence signals quality [

46].

H3. PBQ positively affects consumers’ SPI.

2.4. Perceived Brand Prestige

PBP reflects a brand’s high status, shaped by consumer experience, knowledge, and awareness of competitors [

47]. For a brand to be perceived as prestigious, its core values, quality, and performance must be widely recognized. PBP reinforces consumers’ emotional and rational beliefs, mainly when tangible product differences are minimal [

48]. Studies indicate that sensory and intellectual cues linked to global brands enhance PBP, influencing consumer preferences and loyalty [

49]. Prestige, therefore, is primarily driven by brand quality and consumer perceptions. Consistent with status-signaling/conspicuous consumption and social identity perspectives [

27,

50], PBP operates as a symbolic cue of distinction and group membership, making it a theoretically expected conduit through which PBG can elevate perceived status. Under status-signaling/conspicuous consumption and social identity frameworks, PBP represents a symbolic indicator of distinction and group belonging, making it the logical conduit for translating PBG into perceived status. Global brands often hold higher prestige than local brands due to their exclusivity and premium pricing [

51], particularly in emerging markets where American products are superior [

5]. Consumers may also favor international brands as symbols of cosmopolitanism, sophistication, and modernity [

1]. Additionally, brands demonstrating social and environmental responsibility are perceived as more prestigious [

29]. Empirical evidence consistently supports a significant positive relationship between PBG and PBP [

1,

35,

52].

H4. PBG positively affects consumers’ PBP.

Brand prestige is not immune to adverse effects, as environmental misconduct can negatively impact consumer PIs, regardless of how global or high-quality a brand is. Research by Krishna and Kim [

53] shows that brands accused of environmental irresponsibility increase consumers’ perceptions of moral deficiencies, leading to a higher tendency for boycotts. This highlights the critical role of sustainability in maintaining brand prestige. Viewed through status-signaling/conspicuous consumption and social identity lenses [

50], PBP provides symbolic and self-expressive value that can translate into purchase intentions when prestige is perceived as ethically legitimate and socially responsible.

Sustainability-focused brand strategies have been found to enhance consumer perceptions and directly influence their PIs [

54]. For instance, Panda et al. [

55] demonstrated that increased social and environmental sustainability awareness promotes altruistic consumer behavior, resulting in more excellent PI toward environmentally conscious brands. Similarly, Sun and Yoon [

56] found that ethical consumption awareness elevates consumer willingness to pay premium prices for sustainable products, indicating that brands with solid environmental responsibility gain prestige, strengthening consumer PIs. Research in Taiwan and Indonesia, focusing on iPhone and HTC, further supports that while perceived quality has a more substantial impact, brand prestige still influences sustainable product preferences [

57]. Consequently, PBG directly enhances PBP, strengthening PI [

29]. Moreover, research by Hatzithomas et al. [

33] in Greece—an influential tourism destination—indicates that sustainability perceptions enhance both the globalness and prestige of brands, thereby positively influencing PI.

H5. PBP positively affects consumers’ SPI.

2.5. Brand-Cause Fit

Cause-related marketing (CRM) is a strategy where a company donates a portion of its profits to a cause aligned with the company’s and its customers’ shared values [

58]. Grounded in attribution theory and congruence-based perspectives (schema congruity/match-up logic), BCF captures the extent to which consumers perceive a coherent fit between a brand’s identity and its socially responsible initiatives. According to attribution theory, individuals seek rational explanations for their environment, using causal attributions to interpret events [

59]. Within CRM, BCF refers to the perceived alignment between a brand’s values and its socially responsible initiatives [

35].

BCF involves the congruence between a brand’s, and a cause’s, values, shared customer bases, and alignment with consumer perspectives [

60,

61]. While CRM fosters emotional connections and positive brand perceptions, skepticism can arise if consumers view the initiatives as self-serving rather than altruistic. Unlike philanthropy, CRM aims to maximize profit and enhance the brand image by creating a socially responsible brand identity [

62]. Consumers cognitively evaluate BCF before accepting a brand’s connection to a cause. Due to their perceived quality and prestige, global brands enhance the credibility of their social responsibility efforts. Research shows that PBG increases the consistency and trustworthiness of a brand’s initiatives, boosting consumer loyalty and brand prestige [

28,

29]. Becker-Olsen et al. [

63] found that consumers in Mexico and the United States generally view global brands’ corporate motivations and reputations more favorably than local brands. Aligning CSR initiatives with global consumer culture improves perceptions, as emphasizing globalness often leads to higher evaluations of a brand’s efforts [

64].

H6. PBG positively affects consumers’ BCF.

Researchers have shown that CRM programs can enhance consumer perceptions and increase PIs [

65,

66], although effectiveness may hinge on perceptions of BCF and underlying motivations. Simply viewing a company as “successful” or “ethically conscious” does not guarantee CRM success; still, Nan and Heo [

67] suggest that any good-cause link can benefit a firm, regardless of its relevance. Studies confirm BCF’s positive influence on cognitive, emotional, and behavioral outcomes, and the relationship between brand globalness and PIs in CRM contexts [

30,

68,

69]. While strong BCF can positively influence purchases, weak brand–cause alignment may fail to affect consumer perceptions or PIs [

52]. Conversely, higher alignment between a brand and its social cause boosts credibility and PIs [

70]; poor alignment can hinder PIs [

71]. Furthermore, consumers who detect inconsistencies between a brand’s purpose and its social responsibility efforts increasingly penalize brands for irresponsible behavior [

72]. Perceived CSR enhances brand credibility and reputation, thereby raising PIs, supporting BCF’s indirect effect on SPIs [

73]. When consumers perceive a strong brand-mission–cause alignment, they are more likely to trust the brand and be motivated to purchase.

H7. BCF is positively related to SPI.

2.6. The Mediating Role of PBP, PBQ, and BCF

Consumers’ perception of a brand as global can significantly influence their PIs (Steenkamp et al., 2003; however, rather than being a direct relationship [

1,

3], this connection is frequently shaped by various mediating variables, as emphasized in the literature. Akram et al. [

5] comprehensively analyzed previous studies and proposed that PBQ and PBP fully mediate the relationship between PBG and PI. In a study conducted in Vietnam, Vuong and Giao [

29] found that both PBP and PBQ partially mediate the effect of PBG on PI. This finding suggests that the influence of PBG on consumer behavior is indirect, occurring through the brand’s prestige and quality. A similar study by Hussein and Hassan [

74] also supports the idea that PBG increases the likelihood of brand purchase through factors such as brand prestige and quality. However, Moslehpour et al. [

46] found that PBQ partially mediates the relationship between PBG and PI, but PBP does not mediate in this relationship. These varying results indicate significant differences in the research surrounding PBQ- and PBP-mediating roles.

H8a. PBG affects SPI mediated by PBQ.

H8b. PBG affects SPI mediated by PBP.

Attributional reasoning suggests that consumers infer a brand’s motives and sincerity from the perceived congruence between its identity and its social/environmental initiatives [

60]. When BCF is high, consumers ascribe intrinsic, value-driven motives to the firm, skepticism drops, and SPI rises; when BCF is weak, initiatives are seen as opportunistic impression management [

67]. This mechanism underpins both the direct BCF→SPI link (H7) and the indirect PBG→BCF→SPI path (H8c): being global is insufficient unless sustainability efforts are perceived as authentically “fitting” the brand’s mission and capabilities [

29,

30,

33]. BCF strengthens consumers’ trust in a brand and their belief in its mission [

72,

75,

76]. When global brands align their actions with social responsibilities, consumers perceive them as providers of quality products and as ethical leaders contributing to society. This perception can influence consumers’ SPIs. Le, et al. [

77] demonstrated that perceived CSR enhances consumers’ brand perceptions and PIs. PBG can affect PI by mediating brand credibility and social responsibility. Baek et al. [

30] also found that millennial consumers’ perception of the globalness of sportswear brands positively influences BCF. Mendini et al. [

75] explored how the alignment between a brand and its cause reduces consumer skepticism and increases purchase willingness. Their study demonstrated that BCF, by reducing consumer skepticism, increases consumers’ trust in the brand, which in turn positively influences their PIs [

75]. Therefore, when global brands act consistently with their social responsibilities, they are likely to positively shape consumer perceptions of the brand, which strongly mediates SPI. This finding reassures us about the impact of brand alignment on consumer behavior.

H8c. PBG affects SPI mediated by BCF.

2.7. The Moderating Role of CE

CE, driven by moral and economic motives, leads consumers to view domestic products as a moral obligation and foreign goods as potentially harmful to the local economy [

21,

78,

79]. In contrast, non-ethnocentric consumers weigh objective factors, such as price and quality, without the same economic concerns. As a result, CE can hinder loyalty to foreign brands, particularly in developed markets [

80].

Research shows CE significantly shapes consumer attitudes, influencing the link between perceived brand attributes and PIs [

81,

82,

83]. Ethnocentric consumers often favor domestic brands—even if foreign ones offer superior quality or price—because such choices reflect economic support and cultural values [

84]. Consequently, CE can magnify the positive impact of domestic brand quality on SPIs by reinforcing perceptions of sustainability [

79]. CE also boosts the link between a brand’s BCF and SPI. Ethnocentric consumers view sustainability and social responsibility as moral duties, heightening the effect of brand initiatives that emphasize these values [

18,

85].

However, when CE is strong, global brands face reduced effectiveness in their sustainability strategies. Ethnocentric consumers often see global brands as symbols of foreign dependence, which diminishes the impact of PBG on SPI [

29,

86]. Recent worldwide issues (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) have further heightened consumer scrutiny of foreign brands’ sustainability claims, compelling global brands to adapt their strategies to local values [

87,

88]. Highly ethnocentric consumers also view local brands as key expressions of national identity and culture, overshadowing even prestigious global brands [

89]. Supply chain issues and doubts about global brands’ transparency—exacerbated during the pandemic—can reinforce negative perceptions among those with high CE, who feel compelled to support local brands [

90,

91]. CE does not uniformly suppress global brands; it reweighs which brand cues are considered legitimate, prioritizing locally beneficial, morally framed signals over prestige-laden globalness claims [

86,

87,

88,

89]. Thus, the hypotheses are as follows:

H9a. CE strengthens the relationship between PBQ and SPI.

H9b. CE strengthens the relationship between BCF and SPI.

H9c. CE weakens the relationship between PBG and SPI.

H9d. CE weakens the relationship between PBP and SPI.

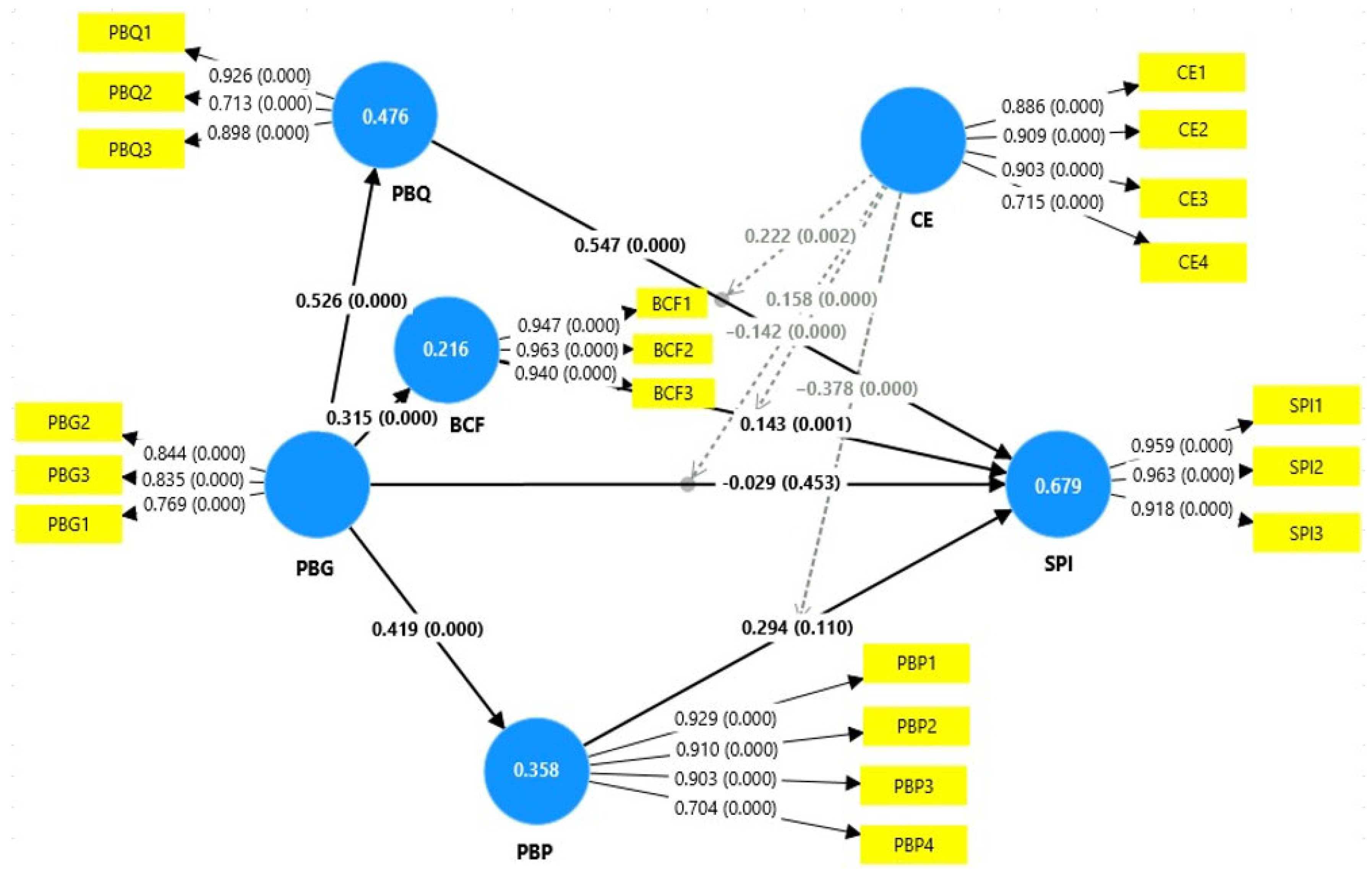

Figure 1, below, illustrates the conceptual model proposed in this study, which explores the relationships between PBG and SPI.

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

This study adopts a longitudinal research design to explore changes in consumer perceptions over time. Longitudinal designs are particularly effective for analyzing time-dependent variations, as they involve repeated data collection from the same individuals, facilitating the observation of individual variability and environmental influences [

92,

93]. This approach allows for analyzing both the direction and rate of change, offering a more precise depiction of causal relationships through ongoing measurement [

94].

The study’s design covers two critical periods: 2021 and 2024. This timeframe enables an examination of the long-term effects of the pandemic and global economic uncertainties on consumer behavior. Specifically, it investigates shifts in consumer attitudes towards sustainability, brand prestige, and ethnocentric tendencies, especially in response to pandemic-driven disruptions in global supply chains. By gathering data from the same individuals at both points, the study ensures consistent tracking of consumer awareness and behavior changes.

The study conducted in Turkey, a developing economy, offers insights into the dynamics of consumer perceptions within emerging markets. The longitudinal design provides a deeper understanding of how increasing interest in local production has influenced trust in global brands in countries like Turkey. Collecting data from the same sample cohort allows a more precise evaluation of how evolving social and economic conditions have impacted factors such as PBG, PBP, and CE.

PLS-SEM was used to test the proposed hypotheses and analyze the structural model. This method provides robust results for path analysis and relationship testing among multiple variables [

95]. Data analysis was performed using SmartPLS 4 software, which is a powerful tool for structural model validation and reveals complex relationships among variables [

96].

PLS-SEM was chosen over covariance-based SEM (CB-SEM) because the study’s emphasis lies in prediction-oriented modeling with multiple mediators and latent interaction terms, conditions under which PLS-SEM performs robustly without requiring multivariate normality or very large subgroup samples. In addition, the use of five-point Likert indicators and complex moderated mediation paths (H8a–c; H9a–d) made PLS-SEM’s composite-based and bootstrap-driven estimation preferable.

To test robustness, we re-estimated all models using the consistent PLS algorithm (PLSc) and increased the bootstrap resamples to 10,000. The direction and significance of the hypothesized paths remained stable (|Δβ| < 0.03). Auxiliary OLS regressions on construct scores replicated the substantive pattern of direct and interaction effects, indicating that our findings are stable across alternative estimation procedures.

3.2. Sampling

The sample for this study consists of 415 participants, from whom data were collected across two different time periods, specifically in 2021 and 2024. This sample size exceeds the minimum recommended for studies utilizing the PLS-SEM method [

97]. The same participants were surveyed at both time points, with the initial participant list from 2021 being recorded and re-contacted in 2024 to collect follow-up data. This approach was employed to ensure a reliable tracking of changes in consumer perceptions over time by obtaining data from the same individuals.

The study sample comprised individuals aged 18 and above, as this age group is legally capable of making independent consumer decisions and is likely to have personal income [

98]. Additionally, the prior literature emphasizes that this age range allows for a more accurate analysis of decision-making processes in consumption behavior studies [

99]. To verify participant eligibility, a screening question was used to confirm that respondents met the age requirement before participating in the survey.

Participants from the 2021 survey were eligible to participate again in 2024, maintaining their validity as part of the sample unit over the study period. The absence of significant demographic changes among participants ensured the representativeness and reliability of the sample [

100]. Retaining the same sample group is crucial for the validity of longitudinal studies, as it allows for more precise observations of changes in attitudes and behaviors over time [

94].

Table 1 outlines the demographic characteristics of the participants who participated in the study in 2021 and 2024.

The study was primarily bound to Turkey due to its longitudinal design: retaining and re-contacting the same 415 respondents across a three-year interval required a single, clearly delimited sampling frame. Moreover, Turkey constitutes a paradigmatic emerging-market setting, characterized by rapid exposure to global brands, volatile macroeconomic conditions, and heightened debates around national identity and sustainability. These contextual attributes, which are shared by many developing economies, render Turkey a theoretically informative case for examining how perceived brand globalness, sustainability cues, and ethnocentrism evolve. Accordingly, our claims target analytic generalization—deriving theoretically transferable mechanisms—rather than statistical generalization to all developing countries.

In line with IRB guidance and to avoid respondent reluctance on sensitive identity items, we did not collect detailed regional or ethnic background data. Given the sample size, further subdivision would also have yielded underpowered cells for multi-group analysis. Instead, CE was measured to capture identity-laden variance at the individual level.

All 415 individuals surveyed in 2021 were successfully re-contacted and participated again in 2024, yielding an attrition rate of 0%. To rule out demographic drift, we compare the distributions of gender, age cohort, education, income, and occupation across waves. While chi-square tests showed no significant differences for gender and education (e.g., χ2(1) = 0.00, p = 1.000; χ2(2) = 0.999, p = 0.607), age-, income-, and occupation-related shifts were statistically detectable and, yet, exhibited very small effect sizes (Cramer’s V ≤ 0.18) consistent with natural changes (e.g., aging, inflation-driven income reclassification). These results suggest that longitudinal comparisons are unlikely to be confounded by changes in sample composition.

3.3. Data Collection and Measurement Instruments

Data was meticulously collected through online surveys using a convenience sampling method to explore whether sustainable purchase behavior changed between 2021 and 2024 based on shifts in consumer perceptions of global brands.

The survey scale items were initially drafted in their original language and translated into Turkish. To prevent any potential loss of meaning due to conducting the research in a different culture and language, the questions were revised using the back-translation method with the assistance of several English language experts. A pilot study involving 65 participants was conducted to ensure the highest level of accuracy and minimize any errors related to the sample. The survey was finalized after making minor adjustments as required by the pre-test.

The data collection process followed the same procedure in both periods, with participants granting necessary permissions via an “informed consent form.” Confidentiality principles were strictly upheld throughout the study. The first question served as a screening measure to ensure that only individuals aged 18 and above could participate.

This research aims to objectively capture general consumer behavior and perceptions within a robust ethical framework. Therefore, no brand names were mentioned to minimize the influence of participants’ personal opinions about specific brands. The study aims to measure how a globally recognized brand known for its sustainability activities is perceived and how this perception—along with its prestige, quality, and alignment with sustainability goals—affects consumers’ SPIs. To achieve this, a neutral text introducing the brand was added at the beginning of the survey, creating an ethical framework that serves the research questions (see

Appendix B,

Table A2). The text objectively explains the brand’s general mission and sustainability commitment without praise or criticism, ensuring the study’s objectivity. To prevent bias and ensure that participants could evaluate the brand’s globalness, prestige, and quality without manipulation, neutral language was used, minimizing the risk of manipulation.

To minimize response biases, we (i) guaranteed full anonymity and confidentiality, collecting no personally identifying information; (ii) used neutral wording and retained a reverse-coded item to lessen acquiescence and social desirability pressures; (iii) kept the instrument concise (20 core items) and refined it through a 65-person pilot to reduce respondent fatigue; and (iv) randomized the order of item blocks in the 2024 wave to discourage patterned responding. We also screened for straight-lining and excessively short completion times; no cases exceeded our pre-specified thresholds, suggesting minimal careless responding.

We deliberately refrained from naming actual global or local brands to avoid familiarity, halo, and reputation biases that could contaminate respondents’ evaluations of PBG, PBQ, PBP, and BCF. By relying on neutral vignettes and scenario, we prioritized internal validity and construct purity, capturing respondents’ abstract perceptions rather than brand-specific attitudes. This trade-off aligns with prior research that operationalizes brand perceptions using generic stimuli to minimize idiosyncratic brand effects. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that using real brands could enhance ecological validity; therefore, we encourage future studies to triangulate our findings with brand-specific experiments or field data.

Participants were presented with a brief scenario before asking questions related to brand–cause fit. This scenario, which described a realistic sustainability activity conducted by a brand without using any visuals or labels (see

Appendix B,

Table A3), was designed to assess participants’ SPIs. The scenario included informative content on CRM activities and aimed to measure participants’ reactions within a realistic context, free from biases associated with any brand. This approach was crucial in understanding participants’ SPIs and their responses to CRM activities.

The first section of the survey consists of 20 items, evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale designed to help understand consumers’ SPIs toward global brands. PBG was measured using a three-item scale that assesses consumers’ perceptions of whether a brand is marketed outside their home country. This scale, developed by Steenkamp et al. [

1], reliably reflects consumers’ perceptions of a brand’s international recognition. PBP was assessed using a four-item scale adapted from the work of Han and Terpstra [

101]. Additionally, PBP was measured with a 4-item scale equivalent to the original 17-item Consumer Ethnocentrism Scale (CETSCALE) developed by Shimp and Sharma [

21], with high reliability, as validated by Steenkamp et al. [

1]. PBQ was measured using a three-item scale developed by Keller and Aaker [

102]. The BCF variable, reflecting CRM activities, was measured using a 3-item scale developed by Kanta et al. [

103]. Lastly, SPI was assessed using a scale adapted from the work of Lavuri and Susandy [

104]. The original scale items are presented in the appendix (see

Appendix A,

Table A1).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Evaluation

In this study, Confirmatory Factor Analysis was conducted to evaluate the validity and reliability of the data collected in 2021 and 2024. The outer loadings of each construct in the measurement model were found to be significant for both years, with factor loadings ranging from 0.733 to 0.971. This range is above the threshold of 0.70, indicating that the indicators loaded well onto the constructs and provided robust measurements [

105].

The reliability and validity of the constructs used in the study were assessed using Composite Reliability (CR), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and Cronbach’s alpha. CR values ranged from 0.857 to 0.973 for all constructs, exceeding the 0.70 threshold, which indicates high internal consistency and reliability [

105]. Similarly, the AVE values ranged from 0.653 to 0.924, all above the acceptable level of 0.50, indicating that each construct had sufficient convergent validity with its respective indicators [

106]. Although the AVE for PBG decreased from 0.709 (2021) to 0.667 (2024), it remained well above the 0.50 criterion, suggesting only a modest broadening in how respondents construed globalness rather than a validity threat. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.758 to 0.959, again exceeding the 0.70 threshold, which confirms strong internal consistency for the constructs [

100]. These results indicate that the constructs have a high level of reliability.

Multicollinearity refers to a high correlation between indicators, which can negatively affect the predictive power of a model [

105]. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) is used to detect multicollinearity, and VIF values below five indicate no multicollinearity issue [

105]. In this study, VIF values generally ranged from 1.3 to 4.4, suggesting that multicollinearity was acceptable and did not compromise the model’s predictive power. However, some constructs, such as BCF, had VIF values above three, indicating a stronger correlation between their indicators.

Table 2 provides a comparative analysis of the reliability and validity values of the constructs measured in 2021 and 2024. Notably, the PBG construct, which was measured with high reliability and validity in 2021 (α = 0.796, CR = 0.879, AVE = 0.709), showed a slight decrease in these measures in 2024 (α = 0.758, CR = 0.857, AVE = 0.667). This decline, while not significant, suggests a potential shift in the consistency of the construct’s measurement over time. However, it’s important to note that the construct remained within acceptable reliability and validity thresholds in both years. These observed changes in reliability and validity may indicate shifts in how the constructs are measured over time, which could have significant implications for future research and practice.

In 2021, PBQ exhibited strong reliability (α = 0.851, CR = 0.910, AVE = 0.771). However, in 2024, the reliability and validity of this construct showed a significant decline (α = 0.777, CR = 0.869, AVE = 0.694). The decrease in AVE suggests that the consistency of perceptions regarding brand quality has diminished. It can be said that consumers have developed different views on PBQ over time, leading to a less clear perception.

For PBP, reliability and validity were adequate in 2021, with α = 0.830, CR = 0.882, and AVE = 0.653. However, in 2024, the reliability and validity of this construct increased (α = 0.893, CR = 0.922, AVE = 0.750), indicating that the construct became more consistent. This result suggests that consumers have developed a stronger awareness of brand prestige over time, and the prestige of brands has become more important to consumers. This may indicate that the reputation of brands has strengthened over time.

BCF demonstrated very high reliability and validity values in both years. In 2021, α = 0.959, CR = 0.973, and AVE = 0.924 were obtained, and in 2024, although these values experienced a slight decline, they remained at very high levels (α = 0.946, CR = 0.965, AVE = 0.903). The consistently strong results across both years indicate that consumers perceive the alignment of brands with their social responsibility projects in a highly consistent manner.

The CE construct exhibited high reliability and validity in 2021, with α = 0.904, CR = 0.933, and AVE = 0.776. In 2024, there was a slight decrease in its reliability and validity (α = 0.885, CR = 0.917, AVE = 0.735). While this slight decline indicates a minor reduction in the construct’s measurement quality, it remained within acceptable reliability and validity thresholds in both years.

SPI showed strong reliability and validity results in 2021, with α = 0.926, CR = 0.953, and AVE = 0.871. In 2024, this construct became even stronger (α = 0.942, CR = 0.963, AVE = 0.896), indicating that the construct was measured more consistently and its reliability increased. These results not only suggest that the SPI construct became more robust in the measurement model over time but also demonstrate potential improvements in the field of marketing research in terms of reliability, fostering a sense of optimism.

4.2. Discriminant Validity Assessment

Discriminant validity helps determine whether each construct in a model is unique and maintains its own independent structure. In this study, both the Fornell–Larcker criterion and the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio [

105] were employed to verify that constructs are adequately differentiated from one another, preventing overlap or confusion within the model.

Under the Fornell–Larcker criterion, the square root of a construct’s AVE should exceed its correlations with all other constructs, indicating that it accounts for more variance in its own items than in those of other constructs [

106]. Analyzing all constructs for 2021 and 2024 confirmed that each construct’s AVE square root surpassed its inter-construct correlations, thereby confirming discriminant validity in both years.

The outcomes of this discriminant validity check appear in

Table 3, where the diagonal entries (the square roots of each construct’s AVE, shown in italic) exceed the correlations with other constructs, reinforcing that each construct is distinctly measured.

The HTMT ratio is another important method that measures discriminant validity more sensitively and helps to determine whether constructs are overlapping with each other [

106]. HTMT values are generally expected to be below 0.85 or 0.90 [

107]; exceeding these thresholds indicates excessive similarity between two constructs and suggests that discriminant validity is compromised. When examining the HTMT ratios for the years 2021 and 2024 in

Table 4, it is observed that all values between the constructs remain below 0.90. This indicates that the relationships between the constructs are within acceptable limits and that discriminant validity is achieved in both years. Therefore, according to the HTMT criterion, the independence of the constructs is maintained, confirming that the model has sufficient discriminant validity.

4.3. Predictive Power and Quality of the Model

The quality of a structural model is assessed based on its fit, explanatory power, and predictive strength. The R

2 coefficient reflects how well independent variables account for the variance in dependent variables, with 0.19, 0.33, and 0.67 indicating low, medium, and high explanatory power, respectively [

108]. In 2024, the explanatory power for SPI was high (R

2 = 0.679), while PBQ, PBP, and BCF showed medium to low power (R

2 values of 0.476, 0.358, and 0.216, respectively). By comparison, in 2021, SPI had a slightly higher R

2 (0.703), with similar values for other constructs, indicating stable explanatory power over time.

The Q

2 coefficient, measuring predictive strength, categorizes values above 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 as low, medium, and high predictive power, respectively [

109]. In 2024, the Q

2 for SPI was 0.588, demonstrating high predictive strength, while the other constructs showed moderate predictive power. SPI’s predictive power declined slightly from 2021 (Q

2 = 0.675) but remained the strongest among all constructs.

SPI maintained the highest explanatory and predictive power across both periods, although it slightly decreased in 2024. The model’s predictive strength for other constructs remained consistent, underscoring the robustness of the findings. Refer to

Table 5 for a detailed comparison of R

2 and Q

2 values. To preclude concerns that the comparatively high R

2 values are a scenario artefact, we note that they primarily stem from the theoretically tight interrelations among PBG, PBQ, PBP, BCF, CE, and SPI; this is further supported by strong Stone–Geisser Q

2 values (e.g., Q

2_SPI = 0.588 in 2024) and stable coefficients across PLSc and OLS re-estimations (Δβ < 0.03; see

Appendix C,

Table A4.

SRMR is a fit index that measures the difference between the predicted correlation matrix and the observed correlation matrix [

110]. In 2021, the SRMR value was 0.068, while in 2024, it slightly increased to 0.077. Since both SRMR values are below 0.08, it can be concluded that the model has an acceptable fit in both years [

109]. This indicates that the model aligns well with the observed data in both 2021 and 2024. Additionally, NFI is another index that measures how well the model fits the data, with values ranging between 0 and 1. If the NFI value is 0.90 or above, the model is considered to have a good fit. In 2021, NFI = 0.949, while for 2024, this value decreased to 0.916. Despite this decrease, both NFI values are above 0.90, indicating that the model exhibits good fit with the data in both years. As shown in

Table 5, the SRMR and NFI values reflect the model’s overall fit across the two time periods.

4.4. Hypotheses Testing Results

The path analysis results in

Table 6 provide insights into the relationships between key constructs over time.

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 depict the structural equation models for 2024 and 2021, presenting path coefficients and explained variances. The significance of the hypotheses was tested for both years using bootstrapping with 415 samples, ensuring result reliability [

109].

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 illustrate the structural equation models for 2024 and 2021, respectively, including path coefficients and explained variances (R

2) for each construct. These figures display the relationships between latent variables such as PBG, PBQ, Perceived PBP, BCF, CE, and SPI. The path coefficients indicate the strength and significance of the relationships between the constructs, providing insight into the model’s explanatory power over time.

Underpinning shifts in path significance are detailed in

Appendix D,

Table A5, which reports construct-level means and standard deviations for 2021 and 2024 (ΔMean, Cohen’s

d).

H1 was rejected in both years, as PBG did not have a significant impact on SPI (2021: β = 0.024, p > 0.05; 2024: β = −0.029, p > 0.05). Conversely, H2 and H3 were strongly supported, indicating that PBG significantly influenced PBQ (2024: β = 0.526, p < 0.001; 2021: β = 0.394, p < 0.001), and PBQ significantly impacted SPI (2024: β = 0.547, p < 0.001; 2021: β = 0.452, p < 0.001). H4, representing the effect of PBG on PBP, was significant in both years (2024: β = 0.419, p < 0.001; 2021: β = 0.399, p < 0.001). However, H5, which examines PBP’s impact on SPI, was only significant in 2021 (β = 0.151, p < 0.001) but not in 2024 (β = 0.294, p > 0.05). Notably, although PBP exhibited higher reliability and validity in 2024, its direct effect on SPI became nonsignificant. This pattern indicates that enhanced psychometric consistency does not necessarily translate into sustained predictive power, a point further elaborated in the Discussion. Both H6 and H7 were supported, showing significant effects of PBG on BCF (2021: β = 0.409, p < 0.001; 2024: β = 0.315, p < 0.001) and BCF on SPI (2021: β = 0.233, p < 0.001; 2024: β = 0.143, p < 0.001), indicating that the influence of globalness and cause alignment on SPI persisted across both years, though with varying strengths.

For H8a, the effect of PBG on SPI through PBQ was strongly supported in both 2021 (β = 0.178, p < 0.001) and 2024 (β = 0.288, p < 0.001). Notably, this relationship became stronger in 2024, indicating a dynamic evolution in the impact of PBG on SPI through the perception of brand quality over time. For H8b, the effect of PBG on SPI through PBP was supported in 2021 (β = 0.060, p < 0.001). However, this relationship was not found to be significant in 2024 (β = 0.123, p = 0.112 > 0.05), leading to the rejection of the hypothesis. This suggests that the impact of brand prestige on SPI has decreased or become more uncertain over time. On the other hand, for H8c, the effect of PBG on SPI through BCF was supported in both years, though this relationship slightly weakened in 2024 (β = 0.045, p = 0.005 < 0.05). This result suggests that the impact of brand globalness on SPI through social responsibility projects became less pronounced in 2024 compared to 2021.

The H9 hypotheses assess CE’s moderating impact on SPI through interactions with different constructs. In 2021, the interactions between CE and PBQ (β = 0.002, p = 0.965), BCF (β = −0.034, p = 0.494), and PBG (β = −0.047, p = 0.205) were not significant, indicating limited influence on purchase intentions. However, in 2024, CE significantly moderated these relationships: it positively affected PBQ-SPI (β = 0.222, p = 0.002) and BCF-SPI (β = 0.158, p < 0.001), but negatively impacted PBG-SPI (β = −0.142, p < 0.001), suggesting increased consumer resistance toward global brands. Similarly, CE’s interaction with PBP was not significant in 2021 (β = 0.061, p = 0.158) but became strongly negative in 2024 (β = −0.378, p < 0.001), indicating reduced impact of brand prestige among ethnocentric consumers. These findings highlight how CE’s influence on brand perceptions evolved over time, emphasizing its growing importance in brand strategies, particularly for global brands and social responsibility initiatives.

5. Discussion

This study examined the effect of global dynamics between 2021 and 2024 on consumer behavior and the evolution of consumer preferences towards global brands. The study also delved into the influence of CE on the effectiveness of global brands’ sustainability strategies over three years. The findings unveiled significant shifts in consumer perceptions, particularly emphasizing the distinct effects of factors such as CE and brand prestige.

Our finding that PBG had no direct effect on SPI in either wave diverges from studies that reported a positive globalness–behavior link [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38] but converges with work suggesting that globalness often acts indirectly through quality and credibility cues [

46,

47]. We argue that, in the post-pandemic, high-uncertainty context, consumers no longer treat “being global” as a sufficient trigger; instead, they decode PBG into substantive signals (PBQ, BCF), and the rise of CE in 2024 further attenuated any residual direct appeal of globalness.

While brand prestige strongly influenced consumers’ SPI in 2021, this relationship lost significance by 2024. This indicates that the perceived prestige of global brands either weakened over time or became less important for consumers in the context of sustainability. Several reasons may explain this shift. First, disruptions in global supply chains, difficulties in sourcing raw materials, and rising logistics costs following the pandemic increased the costs for global brands [

111,

112,

113]. These rising costs further inflated prices, particularly in the luxury and premium brand segments [

114]. As consumers faced more significant economic uncertainty during the pandemic, the price increases in global brands may have been perceived as excessive or unjustified, thereby damaging the prestige of these brands. In this context, consumers may have viewed non-transparent price hikes as a loss of prestige. Transparency, regarded as a key element of brand trust, is crucial, and its absence can harm a brand’s prestige from the consumer’s perspective [

115]. Moreover, consumers who became more sensitive to sustainability issues may have lost trust in brands that could not justify their price increases.

This pattern departs from earlier evidence of a positive prestige effect on purchase intentions [

1,

35,

52] and supports emerging findings that symbolic status cues weaken when consumers prioritize verifiable sustainability performance and moral legitimacy [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Thus, prestige remains psychometrically coherent but behaviorally inert unless it is underpinned by transparent social and environmental proof—an inertia intensified by CE’s negative moderation of PBP in 2024.

The apparent contradiction between the strengthened reliability of PBP in 2024 (α = 0.893; CR = 0.922; AVE = 0.750) and its diminished effect on SPI can be resolved by distinguishing measurement consistency from behavioral salience. Reliability indices denote that respondents converged more tightly on what constitutes ‘prestige’; however, prestige no longer functioned as a decisive heuristic for sustainable purchasing. Three interrelated mechanisms help explain this decoupling. First, consumers’ post-pandemic value calculus shifted from symbolic status benefits to substantive sustainability credentials, rendering quality and cause-alignment more diagnostic of ethical value than prestige. Second, competitive mediation likely occurred: once PBQ and BCF absorbed variance linked to credible sustainability signals, PBP added little incremental explanatory power. Third, the significant strengthening of CE in 2024—together with its negative interaction with PBP—suggests that prestige, often connoting foreignness or elitism, became less persuasive (or even counterproductive) for ethnocentric consumers. In short, the construct of prestige remained coherent but lost motivational potency under heightened ethical scrutiny and nationalistic sentiment. Consistent with this interpretation,

Appendix D,

Table A5 shows only a modest drop in PBP (ΔMean = −0.14) but a much larger decline in SPI (ΔMean = −0.85), while PBQ and BCF retained or increased their salience—limiting the incremental explanatory power of prestige in 2024.

The waning impact of prestige likely carries distinct implications for luxury versus mass-market brands. For luxury brands, where symbolic value is central, prestige erosion in the face of heightened sustainability scrutiny suggests a strategic pivot toward verifiable environmental and social performance. Mass brands may benefit more directly from strengthening their perceived quality and local cause alignment. Category-level heterogeneity also matters as products with high public visibility (e.g., fashion, electronics) may retain some prestige leverage, whereas utilitarian categories may be driven almost entirely by substantive sustainability cues. Finally, while Turkey is a paradigmatic emerging market, we encourage comparative longitudinal work across other emerging economies to assess whether similar post-pandemic shifts in prestige salience and ethnocentrism occur under differing institutional logics.

Another critical factor is the significant changes in consumer values and purchasing motivations post-pandemic. High inflation and globally rising living costs have forced consumers to manage their budgets more carefully. The global growth rate for 2023 was 3.1%, a lower rate than the pre-2008 financial crisis period [

116]. This slowing growth has led to more cautious and needs-based consumer behavior. Following the pandemic, consumers have emphasized sustainability, healthy lifestyles, and social responsibility [

117]. This shift has led to reduced spending on luxury products and a greater focus on essential and health-related goods. A brand must contribute sufficiently to sustainability, social responsibility, or consumer health to ensure its high prices can maintain its prestige. Merely representing luxury is no longer sufficient; consumers now question the real benefits of high prices. Therefore, these factors contributed to the diminishing impact of PBQ on SPI in 2024 compared to 2021.

In contrast, the persistence—and in PBQ’s case, strengthening—of the PBQ→SPI and BCF→SPI paths aligns with prior work that identifies quality and fit as core levers of sustainability-related decisions [

4,

42]. Our longitudinal evidence extends those cross-sectional findings by showing that these utilitarian and moral-congruence cues remain robust under macroeconomic strain and intensified ethical scrutiny.

The moderating effect of CE on SPI has shown significant differences between 2021 and 2024. Hypotheses rejected in 2021 became significant in 2024, revealing how consumer ethnocentrism’s influence on brands has evolved. Given CE’s amplified moderating role in 2024, we further elaborate its strategic implications for global brands in the Managerial Implications section. This result suggests that there may be a shift in the common literature [

118], which states that CE is at a low level in developing countries like Turkey. There may be several reasons for this. CE increased markedly (ΔMean = +0.79;

Appendix D,

Table A5), selectively dampening the influence of globalness and prestige while amplifying quality and cause-fit cues.

Our results, therefore, challenge the assumption of uniformly low or stable CE in emerging markets and resonate with research linking macro shocks to heightened national-identity salience [

18]. CE selectively dampened the impact of globalness and prestige while amplifying PBQ and BCF, indicating that ethnocentric consumers privilege cues signaling local benefit and moral duty. This asymmetric moderation helps reconcile inconsistent findings in prior studies and underscores CE as a context-sensitive, time-variant moderator rather than a static background trait.

First, between 2021 and 2024, tightening global regulations on sustainability [

119] compelled local brands to make more significant efforts to comply with these regulations to compete in global markets. These efforts may have heightened consumer awareness that local products are also environmentally friendly, of high quality, and produced through ethical processes, which, in turn, may have triggered ethnocentric tendencies. This contributed to PBQ becoming significant in 2024.

Another reason is that the wars and economic tensions between 2021 and 2024 led to significant changes in consumer relationships with global brands. The economic uncertainty caused by these conflicts and rising prices led to establishing state-supported markets that offered local products as viable alternatives to well-known global brands. The increased preference for local brands may have strengthened consumer ethnocentrism during this period. Some consumers may also have been driven by the tendency to boycott global brands due to conflicts.

On the other hand, the sense of social solidarity strengthened in the post-pandemic period, leading ethnocentric consumers to identify more with local brands. The BCF, which reflects how much brands contribute to social solidarity, may have substantially impacted ethnocentric consumers more. During this period, consumers may have viewed the social responsibility projects of local brands as a national value, increasing their support for these brands. As ethnocentric consumers increasingly perceived brands’ social responsibility and sustainability efforts as contributing to national interests, they may have begun to place more excellent value on these projects.

The findings of this study provide managers with insights that require long-term strategic changes rather than short-term tactics. First, the absence of a direct effect of PBG on SPI indicates that brands need to go beyond just being ‘global.’ In this context, local brands implementing sustainability and social contribution projects will gain a significant advantage in competing with global giants and building consumer loyalty. These implications should be interpreted within the confines of a single-country panel; their transferability to other emerging markets depends on comparable institutional and macroeconomic conditions.

6. Limitations and Future Research

This study employed a two-wave panel design, following the same Turkish consumers in 2021 and 2024, which enabled a clear view of attitudinal change. Actually, a key limitation is the single-country scope. Although Turkey shares structural characteristics with numerous developing markets, cultural, institutional, and macroeconomic heterogeneity across emerging economies constrains the universal extrapolation of these characteristics. We, therefore, encourage cross-national longitudinal panels and multi-group comparative designs to test whether the temporal dynamics we identify—particularly the strengthening role of consumer ethnocentrism and the weakening salience of prestige—hold under different institutional logics. Such work would clarify which mechanisms are context-bound and which travel across settings. Nonetheless, several constraints warrant acknowledgement and pave the way for richer inquiry.

First, two observation points limit our ability to model nonlinear or shock-driven trajectories. Future projects could utilize latent growth modeling or rolling-panel methods, incorporating at least three data waves to capture turning points triggered by events such as regulatory shifts or geopolitical crises.

Second, cultural scope is restricted to Turkey. Because constructs such as CE, PBG, and PBP are known to interact with national identity narratives, cross-national panels—especially in regions with contrasting political economies—are needed to test boundary conditions and uncover culture-specific versus universal mechanisms.

Because the same cohort was tracked, observed shifts may embed both cohort maturation and period effects (e.g., post-pandemic inflation, currency volatility, supply-chain disruptions specific to Turkey). We collected the second-wave data between 2021 and June 2024; contextual shocks during this window could have amplified ethnocentric sentiment or reweighted sustainability cues. Future multi-cohort or rolling-panel designs could disentangle the cohort from period effects and incorporate macroeconomic indicators directly into the structural model.

Third, the study relies on self-reported intentions. Subsequent work should triangulate survey data with behavioral traces (e-commerce clickstreams, loyalty-card logs) or digital ethnography to mitigate common-method bias. Integrating implicit measures (e.g., response-time tasks or psychophysiological indicators) would further illuminate non-conscious drivers of sustainable purchase behavior.

Fourth, a further limitation is the absence of multi-group analyses across demographic strata (e.g., age, gender, education). Future research should employ stratified sampling or larger panels to ensure sufficient statistical power per subgroup and formally test measurement invariance prior to MGA. Such designs would clarify whether the temporal dynamics we observe vary systematically across socio-demographic segments.

Fifth, while we centered on brand-level variables and sustainability perceptions, we did not model the rapidly evolving techno-social layer that shapes such perceptions. Research could explore how algorithmic curation, influencer credibility, and AI-generated brand content moderate the link between globalness cues and sustainability trust. Machine-learning-based text mining of social media could map real-time sentiment shifts and compare them with panel survey results.

Furthermore, future research could complement this abstracted approach by incorporating real brand stimuli or field data to further enhance ecological validity and verify whether the observed mechanisms hold for specific brand contexts.

Sixth, we did not gather or analyze regional and ethnic background variables, which are potentially salient for ethnocentrism research. Future studies should incorporate subnational identifiers, test measurement invariance across these strata, and assess whether CE’s moderating effects vary by regional or ethnic identity.

Finally, emerging global disruptions—climate extremes, supply-chain re-regionalization, and inflationary shocks—call for scenario experiments that simulate future crises. Multi-generational panels would clarify whether Gen Z’s heightened ethical stance translates into enduring behavior or attenuates as economic pressures mount. By widening temporal scope, cultural diversity, data modalities, and contextual variables, future research can furnish brands with sharper foresight and more adaptive sustainability strategies.

In addition, although our panel experienced no attrition and demographic shifts were negligible in practical terms, future studies could additionally employ formal measurement invariance procedures to ensure further that observed temporal changes are not attributable to subtle shifts in construct interpretation.

7. Conclusions

This two-wave panel study provides the first longitudinal evidence of how PBG intersects with CE, PBQ, PBP, and BCF to shape SPI in an emerging market context. Tracking the same 415 Turkish consumers from 2021 to 2024 reveals three pivotal shifts. First, the direct impact of PBG on SPI remained nonsignificant at both time points, yet its indirect influence via PBQ and BCF intensified, confirming that global stature translates into purchase propensity only when it signals credible quality and verifiable social engagement. Second, PBP’s explanatory power weakened dramatically, highlighting a post-pandemic consumer pivot from symbolic status toward substantive sustainability performance. Third, CE—historically muted in developing economies—rose sharply and now amplifies the effects of quality signals, causing alignment while attenuating the appeal of globalness and prestige.

These trends yield several theoretical contributions. They demonstrate that (i) relationships among PBG, mediators, and SPI are time-variant, cautioning scholars against extrapolating from single-wave data; (ii) prestige is not a universal conduit—its salience erodes when economic strain and ethical scrutiny dominate purchase criteria; and (iii) CE can no longer be treated as a static backdrop in emerging markets but rather as a dynamic moderator that reshapes brand equity pathways as macro-shocks unfold.

The findings urge global brands to move beyond generic “born-global” narratives. True competitive advantage now lies in pairing global reach with locally resonant, transparently reported sustainability commitments and in fortifying perceived quality even under stress in the supply chain. Conversely, domestic firms can leverage the current ethnocentric upswing by foregrounding traceable quality standards and high-impact social initiatives, thus matching or exceeding the credibility of multinational competitors.

Managerial Implications

Building on these results, we offer the following actionable implications for global brand managers. From a managerial standpoint, the sharp rise in CE by 2024 implies that global reach alone no longer guarantees purchase intent; it must be coupled with locally legible value creation. Global brands should, therefore, move beyond symbolic glocalization and invest in substantive localization. First, co-develop and publicly document sustainability projects with domestic stakeholders—such as local NGOs, farmer cooperatives, and universities—so that cause alignment is seen as nationally meaningful rather than externally imposed. Second, elevate perceived quality through traceability and transparency: certify local sourcing where feasible, disclose environmental and social performance with third-party audits, and communicate how the brand’s operations generate domestic benefits (employment, skills transfer, tax revenues). Third, adopt a modular brand architecture that allows for locally resonant sub-brands or limited editions, while leveraging global capabilities, thus mitigating the ‘foreign elitism’ connotation associated with prestige. Finally, recalibrate brand narratives from ‘global superiority’ to ‘global resources, local responsibility,’ foregrounding reciprocity and accountability. These steps align the brand with the moral and economic concerns of ethnocentric consumers, preserving relevance in markets where national identity has become a decisive purchase filter.

The study shows that globalness per se is no longer a purchase trump card; it must be woven into a fabric of trusted quality cues, authentic social purpose, and sensitivity to rising ethnocentric sentiment. By illuminating these evolving dynamics, the research equips scholars, managers, and policymakers with a more precise roadmap for brand strategy in an era where sustainability and local identity jointly define consumer value.