Abstract

The sustainable development of teaching expertise in research-intensive universities remains a critical global challenge. This study investigates the distinctive characteristics of expert teachers—exemplary faculty in research universities—addressing their developmental trajectories and motivational mechanisms within prevailing incentive systems that prioritize research productivity over pedagogical excellence. Employing grounded theory methodology, we conducted iterative coding of 20,000-word interview transcripts from 13 teaching-awarded professors at Chinese “Double First-Class” universities. Key findings reveal the following: (1) Compared to the original K-12 expert teacher model, university-level teaching experts exhibit distinctive disciplinary mastery—characterized by systematic knowledge structuring and cross-disciplinary integration capabilities. (2) Their developmental trajectory transcends linear expertise acquisition, instead manifesting as a problem-solving continuum across four nonlinear phases: career initiation, dilemma adaptation, theoretical consciousness, and leadership expansion. (3) Sustainable teaching excellence relies fundamentally on teachers’ professional passion, sustained through a virtuous cycle of high-quality instructional engagement and external validation (including positive student feedback, institutional recognition, and peer collaboration). Universities must establish comprehensive support systems—including (a) fostering a supportive and flexible learning atmosphere, (b) reforming evaluation mechanisms, and (c) facilitating interdisciplinary collaboration through teaching development communities—to institutionalize this developmental ecosystem.

1. Introduction

In the global competitive landscape of higher education, research-intensive universities face systemic tensions between research-focused evaluation frameworks and their fundamental educational responsibilities. The cultivation of talent is a fundamental purpose of higher education; however, university systems are often dominated by an emphasis on research output. To address this tension and strengthen the educational mandate of universities, China has implemented a series of policy refinements since 2018: The initiative begins with the mandate that “teaching performance is a primary criterion for professional promotion and performance evaluation” [1], progresses to the institutionalization of “faculty teaching engagement metrics” in undergraduate program accreditation [2], and culminates in the 2024 strategic imperative to “advance pedagogical innovation anchored in disciplinary frontiers” [3]. These interventions are designed to create a policy framework that incentivizes instructional excellence. However, cross-national empirical studies demonstrate that research productivity remains the primary factor influencing tenure decisions and resource allocation in elite research-intensive universities [4,5,6]. It is widely recognized among scholars that career advancement is primarily dependent on exceptional research accomplishments rather than on teaching proficiency [7]. In a competitive academic environment, prioritizing research productivity over teaching engagement becomes rational when limited time and energy are available [5,8]. This pattern of institutional avoidance systematically marginalizes teaching, framing it as a low-incentive activity in research-intensive universities.

In this context, a distinct group of scholars has transcended structural constraints: they persistently engage in teaching innovation and have achieved notable recognition (e.g., awards in teaching competitions, excellence in teaching awards, etc.). Nonetheless, these individuals represent merely a minor segment of higher education institution faculty. In China, the Ministry of Education promulgated two pivotal policy directives in 2015 and 2017, respectively, establishing the strategic framework for developing world-class universities and first-rate academic disciplines, known as the “Double First-Class” initiative [9,10]. The institutions included in this officially designated list represent China’s most prestigious research-intensive universities. To illustrate, Zhejiang University—a flagship institution under China’s “Double First-Class” initiative—exhibits an annual average of 81 faculty awards across its 4000+ full-time academic staff; this figure substantially exceeds the collective annual average of 55 awards among all “Double First-Class” universities [11]. Notably, award recipients constitute less than 1% of the total faculty population. They constitute a distinct group characterized as a “critical minority.”

This study investigates the professional trajectories of distinguished teaching faculty—pedagogical experts who constitute a “critical minority” within China’s research-intensive universities—to address a pivotal question: Through what mechanisms can these recognized teaching experts achieve sustainable professional development within predominantly research-oriented institutional contexts? Their developmental pathways carry significant implications for advancing sustainable educational development globally. Our analysis reveals three theoretically significant dimensions:

First, their behavioral logic extends beyond the “economic man” hypothesis, providing a new framework for understanding non-instrumental professional motivations under institutional constraints. Second, as “positive deviants,” their career patterns illuminate effective pathways to pedagogical excellence that coexist with research imperatives. Third, their resilience mechanisms align with SDG4 (Quality Education) objectives, suggesting actionable models for sustainable teaching development.

These findings contribute to both theory and practice by (a) advancing the conceptualization of sustainable faculty development in research-intensive environments; (b) providing empirical evidence for balancing competing academic missions; and (c) proposing institutional innovations that recognize pedagogical expertise as a core component of university ecosystems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Expert Teachers in Teaching

The concept of “expert teachers” was first systematically proposed by American psychologist Robert J. Sternberg in 1995, referring to educators with specialized pedagogical knowledge and competencies [12]. Inspired by the “expert systems” theory in artificial intelligence, Sternberg developed a continuum theory model of teacher professional development from novice to expert. Compared with novice teachers, expert teachers demonstrate multidimensional professional advantages: (1) in the knowledge dimension, they possess an integrated knowledge system including content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and contextual knowledge; (2) in cognitive structure, they develop highly organized “schemata” and “propositional networks” that significantly enhance problem-solving efficiency; (3) at the metacognitive level, they exhibit superior instructional monitoring and regulation abilities; (4) regarding innovation capacity, they display unique pedagogical insight, excelling at redefining problems from multiple perspectives and applying them creatively to teaching practice.

Subsequent research has expanded this theory from various perspectives: Luo Xiaolu focused on the psychological mechanisms of teaching efficacy and monitoring competence [13]; Zhu Yanjun constructed a structural model of pedagogical scholarship [14]; Boshuizen et al. examined knowledge restructuring via case processing [15]; and Wolff investigated the scripted operation of classroom management [16]. Regarding professional qualities, Sato Manabu supplemented dimensions including public mission awareness, “craftsman” spirit, and “listening” ethics [17]. Notably, Ericsson et al. asserted that authentic expert performance must be validated through consistently superior outcomes on tasks representative of the domain, rather than being assessed solely by credentials or reputation [18].

How does one become an expert teacher in teaching? Current research systematically addresses this question through two theoretical perspectives: First, the stage-based theory of pedagogical skill development. This competence-centered approach posits that teaching expertise follows predictable developmental trajectories. The most influential five-stage model proposed by educational psychologist Berliner identifies (1) novice teachers (1–2 years, rule-dependent), (2) advanced beginners (2–3 years, contextual awareness emerging), (3) competent teachers (3–5 years, strategic teaching), (4) proficient teachers (5+ years, holistic teaching), and (5) expert teachers (8–15 years, intuitive decision-making) [19]. Crucially, the theory underscores that achieving expertise requires over eight years of deliberate practice—a highly structured training modality that distinguishes expert teachers from their peers [18]. Vans et al. established six essential dimensions for developing university educators: teaching practice, curriculum design, assessment, educational leadership, pedagogical scholarship, and professional growth—forming a comprehensive framework for cultivating teaching expertise in higher education [20].

Second, the psychological growth theory of professional identity. This perspective emphasizes intrinsic motivation, framing expert teacher development as professional identity formation. Japanese scholar Sato Manabu contends that authentic teaching expertise emerges through “reflective practice” and “action research” guided by a “public mission” [17]. Empirical studies by Chinese scholar Lian Rong reveal (a) the novice-to-proficient transition primarily depends on mastering instructional strategies (fueled by task-oriented motivation), whereas (b) the proficient-to-expert leap requires developing metacognitive teaching abilities (supported by emotional regulation and professional commitment) [21]. Chen Jingjing et al.’s narrative research demonstrates that expert teachers often follow nonlinear trajectories of “vocation awakening–practice challenges–deep reflection-theoretical breakthrough–ideal reconstruction” [22]. Xie Wen et al. highlight the conscious construction of educational philosophy as a hallmark of expert teachers [23].

Existing studies have systematically analyzed the conceptual dimensions and developmental pathways of expert teachers; however, two significant limitations remain: First, the primary emphasis has been placed on K-12 educators whose main professional goal is teaching, while largely overlooking the developmental traits of expert teachers who manage the dual responsibilities of “research-teaching integration” in research-intensive universities. The hiring criteria for research university faculty typically require them to be established experts in specific academic fields, which means they possess mature expert thinking in research dimensions but may remain at novice levels in teaching dimensions. This unique professional background makes it difficult for them to fully align with existing teacher development theoretical frameworks. Taking Berliner’s theory of teacher professional development stages as an example, this theory characterizes novice teachers as “rule-dependent,” manifesting in rigid adherence to prescribed lesson plans. However, research university faculty, by virtue of their domain expertise, possess textbook selection autonomy and content curation authority even at the novice stage, creating fundamental tensions with the rule-dependent paradigm.

Secondly, existing theoretical frameworks do not adequately address the professional growth requirements of research-focused faculty. The growth trajectory of expert teachers in research universities exhibits unique characteristics: rather than developing pedagogical expertise from scratch, they need to effectively transfer their disciplinary expert thinking into teaching practices. This professional transformation process differs fundamentally from traditional teacher development models, potentially following a distinctive pathway. However, existing theories have yet to fully elucidate the inherent mechanisms of this unique developmental process. Taking Berliner’s teacher development stage theory as an example, the framework may need to further differentiate between the developmental pathways of disciplinary content knowledge and teaching competencies to better explain the professional growth characteristics of research university faculty.

To rigorously differentiate between expert teachers in K-12 education and their higher education counterparts, this study introduces the term “expert teachers in teaching” (full designation) with its abbreviated form “teaching experts” to characterize the latter group. This terminological distinction serves to demarcate these conceptually distinct professional categories within their respective educational contexts.

2.2. Institutional Positioning of Teaching Incentives in Research-Intensive Universities

In the institutional design of global research-intensive universities, teaching incentive mechanisms are consistently positioned as secondary to research reward systems, demonstrating notable isomorphic characteristics across national contexts [24].

In the dimension of resource allocation in institutions, global higher education systems exhibit a predominant institutional preference for research investment, manifested through the following dimensions: The UK’s dual-track funding system provides a telling example: The Research Excellence Framework (REF) 2021 allocated approximately GBP 2 billion annually in research-specific funding (accounting for 72% of UKRI’s total grants) [25,26,27], with disciplines rated as “world-leading” receiving 5–10 times the base-level funding. This makes REF ratings existential for departments [28]. In contrast, the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), despite its GBP 1.5 billion annual budget, primarily operates through adjustments to undergraduate tuition fee caps (limited to ±CPI inflation rate), resulting in substantially weaker incentivization effects. This research bias shows transnational consistency. Most European countries employ REF-like systems [29,30], while Chinese research universities similarly favor institutions with strong research performance in funding allocation [31,32]. Concurrently, in the dimension of faculty development, research-intensive universities exhibit systematic research bias in faculty development through four institutional dimensions: hiring criteria [33], evaluation mechanisms [34,35,36,37], reward structure [38,39], and teaching workload allocation [40,41].

This globally isomorphic institutional arrangement, despite its pro-teaching rhetoric, exhibits research-oriented resource allocation and promotion systems that structurally constrain teaching development. Such conditions critically shape faculty trajectories, especially in research universities where the research-teaching tension is most pronounced. Analyzing expert teacher development thus requires institutional contextualization, with the core challenge being an optimal research-teaching balance.

2.3. Motivational Factors in Faculty Teaching Development

Teachers’ sustained motivation for teaching engagement constitutes a complex, dynamic, and multidimensional system, shaped by both external institutional environments and internal identity formation as well as moral drivers.

Given the asymmetric teaching incentive mechanisms relative to research incentives in research-intensive universities, identity theory provides a deeper analytical framework for understanding teacher motivation. Teacher identity is not a static label but an ongoing process of professional self-construction [42]—a continuous reinterpretation of “who I am” and “who I aspire to be” [43]. Notably, not all university faculty equally identify with the “teacher” role. Individual role perceptions—such as “research-focused instructor,” “teaching-oriented researcher,” or “integrated scholar-practitioner”—significantly influence behavioral choices [44,45]. This identity formation is moderated by three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness [46]. Within the teaching domain, key cognitive dimensions include teaching-related self-efficacy [47,48], professional self-concept, and subjective knowledge structures [49]. Contextual factors further shape this process [50]—positive reinforcement: student feedback and peer community support strengthen teaching identity [51,52,53]. Structural barriers: The “research-over-teaching” culture in higher education may undermine such identification [51]. Beyond rational cost-benefit calculations, moral dimensions serve as core motivators. Teaching conscience and professional ethical responsibility provides intrinsic [23], long-term drive, while the development of expert thinking and external support from learning communities creates a synergistic mechanism for professional growth [22].

Thus, under institutional conditions of imbalanced material incentives, greater attention must be paid to the critical role of non-economic compensation mechanisms, particularly through systematic examination of representative cases where intrinsic motivational pathways—such as conscience and the fulfillment derived from teaching.

To sum up, the existing literature on expert teachers has predominantly focused on K-12 educators, with limited exploration of the conceptualization and developmental trajectories of expert teachers in higher education. Given the substantial differences between university and K-12 teachers in terms of career entry points, institutional environments, and professional pressures, their growth may require distinct support mechanisms. Accordingly, this study targets teaching-excellent faculty in research-intensive universities—where the research-teaching tension is most acute—to address three core research questions:

- (1)

- Individual characteristics: What distinguishing traits set these exemplary teachers apart from their peers? Are there notable disparities in their professional backgrounds, skill sets, and personal attributes that contribute to their teaching excellence?

- (2)

- Motivational factors: Given the prevalent research-oriented incentive structures in academia, what factors motivate these educators to surpass basic teaching expectations?

- (3)

- Professional development: Under resource constraints, what unique trajectory characterizes the development of their teaching expertise?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

The selection of research methods must correspond with the research objectives. Given that teachers’ professional growth constitutes a highly personal developmental process, this study employs qualitative methods to enable in-depth exploration of the micro-level dynamics within teachers’ practice. This approach facilitates the documentation of nuanced interactions and affective dimensions that quantitative methodologies frequently fail to capture.

Grounded theory is a systematic qualitative research methodology originally developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967. It employs an iterative process of data collection and analysis to construct substantive theories from empirical data. Unlike hypothesis-testing approaches, it follows a “bottom-up” inductive logic, making it particularly suitable for investigating under-explored phenomena. This study adopts Charmaz’s constructivist version of grounded theory [54], primarily due to its following methodological characteristics: Contextualized theorizing, dynamic coding system, and researcher reflexivity. The methodology was selected based on three key considerations, as Table 1 shows.

Table 1.

Grounded Theory Selection Criteria.

Guided by the constructivist grounded theory approach, this research follows its procedural framework, including participant selection, data collection, and the three-tier coding process (open, axial, and selective coding) [55].

3.2. Methods

3.2.1. Participant Selection

Drawing on the prior literature, this study defines expert teachers in research-intensive universities as those meeting two criteria: First, a teaching experience threshold: Experience threshold. Minimum 8 years of teaching, aligning with Berliner’s developmental stage theory for expertise [19]. Second, demonstrated external validation of teaching excellence. Recipients of provincial/ministerial-level (China’s teaching awards follow a tiered recognition system: university-level, provincial/ministerial-level (including direct-administered municipalities and central government agencies), and national-level. Provincial/ministerial awards represent the highest honor within an administrative/professional domain, with examples including qualifying cases: Beijing Outstanding Educator (provincial), Ministry of Education Teaching Expert (ministerial); non-qualifying cases: Hangzhou Teaching Excellence Award (prefectural-level)) teaching honors (including Distinguished Teaching Awards, Teaching Achievement Awards, and Teaching Competition Prizes) serve as empirical verification of pedagogical expertise.

The study sample consisted of 13 faculty members recruited from Chinese ‘Double First-Class’ universities. All participants had senior academic roles (professor or associate professor) and possessed Ph.D. degrees. Their teaching experience ranged from 8 to 40 years, representing multiple career stages across four disciplinary domains: Humanities and Social Sciences (n = 5), Natural Sciences (n = 8) (including Agriculture (1), Engineering (5), pure sciences (1)). Detailed demographic characteristics of interview participants are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Detailed demographic characteristics of interviewees (13).

3.2.2. Data Collection

The study employed a multi-method data collection approach. The researchers conducted participant observations during collaborative teaching activities with the 13 expert teachers, systematically documenting their instructional practices and professional decision-making processes. Semi-structured in-depth interviews were then carried out, exploring key dimensions including teaching innovation, research-teaching integration, educational technology adoption, and institutional support systems. Each interview lasted between 30 min to 3 h, with all sessions audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, resulting in a more than 200,000-word textual database. Follow-up interviews (2–3 sessions) were conducted with key informants to capture developmental trajectories. To enhance data richness, the study additionally analyzed 30 supplementary documents such as lesson plans, teaching award applications, pedagogical publications, and media reports, which helped identify critical junctures in professional development. Notably, some interviews involved teaching team members to provide multiple perspectives on how institutional contexts shape teaching practices.

3.2.3. Coding Procedures

This study strictly adhered to the three-stage coding process of grounded theory, employing NVivo 20 software for systematic textual analysis. During the open coding phase, researchers conducted line-by-line coding of 200,000 words of interview transcripts. Representative examples of the line-by-line coding process are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Representative examples of the line-by-line coding process.

The initial coding scheme generated approximately 202 open codes. The research team strictly adhered to the constant comparative method of grounded theory, conducting multiple rounds of semantic analysis and conceptual integration. By merging code labels with differing expressions but similar theoretical connotations, 28 core open codes were ultimately refined. Representative consolidation cases included: combining “openness”, “facing difficulties”, and “not avoiding challenges” into “Adversity Resilience”; integrating “persistence”, “determination”, and “never considered quitting” as “Professional Persistence”; and categorizing “sense of achievement”, “self-fulfillment”, and “enjoy teaching” under “Pedagogical Passion.”

In the axial coding stage, the research team performed a deeper theoretical categorization of open codes based on dimensions of expert teachers’ professional characteristics. Taking the code “Adaptability to Disciplinary Application Scenarios” as an example: this code originated from a teacher’s statement that “courses in Discipline A need to be taught using the paradigms of Disciplines B and C to meet their industry demands respectively, but require completely different instructional strategies when returning to Discipline A.” Through multidimensional analysis, the team determined the statement’s core concern was teachers’ dialectical understanding of ontological (Discipline A) versus methodological (Disciplines B/C) cognition, rather than specific teaching behaviors, and thus ultimately classified it under the axial code “2.1 Depth of Disciplinary Cognition.” This rigorous comparative analysis resulted in an axial coding system comprising 10 codes.

In the selective coding phase, building upon the clear characteristic structure presented in the axial coding system, the study ultimately identified five core attributes of expert teachers in research universities. The three-stage coding process is illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Three-level coding process.

To mitigate disciplinary bias, we implemented a tripartite coding system developed through iterative discussions among three researchers: two from educational technology (specializing in technology integration and teacher development, respectively) and one management scholar (focusing on organizational behavior and HR development). The coding process featured (1) blind independent coding → cross-validation and (2) discrepancy resolution through operational definition refinement.

3.2.4. Theoretical Saturation Test

Theoretical saturation verification constitutes a crucial methodological procedure for validating the research credibility in grounded theory studies. The coding process revealed that only one new conceptual category emerged, respectively, from the 10th and 11th interview transcripts, while no additional theoretical dimensions beyond the established framework were identified in the 12th and 13th interviews. These findings substantiate that theoretical saturation has been attained, ensuring the solid theoretical foundation of the research conclusions.

3.3. Ethical Considerations

This paper has been reviewed by the Center for Teaching and Learning Development of China Agricultural University. All participants were senior teachers with significantly longer teaching experience and career tenure than the researcher, ensuring their professional authority in co-constructing interpretations, and the publication of interview content has been consented to by all participants. All identifiable information (e.g., institution names, specific departments, and personal names) was replaced with pseudonyms during transcription. Only professionally relevant metadata (e.g., teaching years of experience, title, discipline category, and teaching awards) were retained for contextual analysis.

3.4. Researcher Reflexivity

The lead researchers of this study, with educational technology backgrounds, initially focused on technology’s impact on university teaching. However, early interviews exposed a more fundamental issue: within the current institutional environment of “emphasizing research over teaching” in higher education, the topic of technology application is actually subordinate to deeper challenges in teacher development. This discovery prompted us to re-examine the priority of our research questions.

This change in understanding was especially clear when comparing Participant 15 and Participant 16: Participant 15 often felt the stress of balancing “teaching and research,” while Participant 16 showed great practical insight by finding smart ways to overcome challenges from the institution. These practices led us to elevate our research theme from “technology adoption” to “expert teacher development,” repositioning technology application as a secondary research dimension. This adjustment to the research framework strictly adheres to the “emergent design” principle proposed by Charmaz [54]. Consequently, we made significant methodological adjustments by adopting purposive sampling to specifically select teachers who have received provincial-level or higher teaching awards as key research participants. Thus, the 16th interviewee effectively constitutes the first valid case for this study’s core research questions.

However, the 16th, 17th, and 18th interviewees further inspired our ‘super teacher’ conceptualization—does academia’s ‘Matthew Effect’ simply depend on where top performers focus their energy? Where does that leave ordinary teachers? Consequently, our focus gradually shifted toward understanding high-achieving teachers’ dilemmas and their coping strategies. Since all participants were senior faculty (often reluctant to discuss personal struggles), we conducted multiple interviews with several subjects. Our findings suggest the ‘super teacher’ phenomenon essentially represents strategic identity construction within specific institutional contexts. These findings led to positioning teachers’ spiritual attributes as the core category in our coding scheme, with all subsequent thematic analyses radiating from this central concept.

4. Results

4.1. Distinctive Characteristics of Teaching Expert

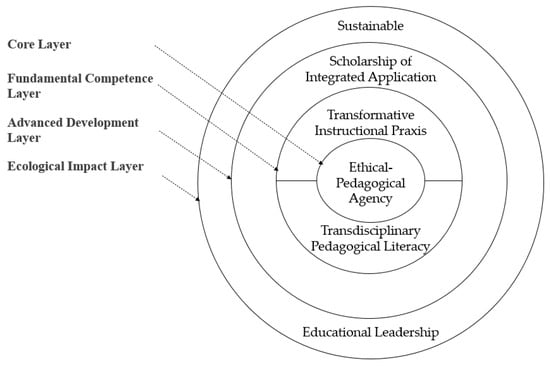

Through in-depth interviews and qualitative analysis of 13 teaching award recipients, this study develops a five-dimensional theoretical mode (as presented in Figure 1) that elucidates the constitutive characteristics of teaching experts in research-intensive universities, employing a four-tier concentric structure with (1) Core Layer (Psychological Attributes) providing sustained motivational energy, (2) Fundamental Competence Layer (Teaching-Specific Competencies) manifesting observable pedagogical skills, (3) Advanced Development Layer (Academic Influence) generating transformative scholarly impacts, and (4) Ecological Impact Layer (Educational Leadership) enabling systemic societal engagement—where core attributes energize competency development while outer-layer practices reinforce inner-layer identity through reflective practice, creating bidirectional interactions that form an integrated empowerment ecosystem through this self-reinforcing professional growth cycle.

Figure 1.

The five-dimensional mode of teaching expert.

4.1.1. Ethical-Pedagogical Agency

Ethical-Pedagogical Agency is the core of the mode. Demonstrating as “conscious idealists,” participants acknowledged systemic imbalances in teaching rewards yet transcended utilitarian calculations through moral commitment. They implemented teaching quality as an intrinsic incentive system that derives satisfaction from learning outcomes. Representative narratives included the following:

“Teaching is ultimately a conscience-driven profession.”(B5)

“While some may perceive our role as insignificant, the sheer volume of students and instructional hours we handle makes any perfunctory approach a moral failure.”(A6)

They also exhibit a resilient professional character in practice, characterized by three core dimensions: adversity resilience, long-term orientation, and professional persistence. Representative narratives included

“With my challenge-loving nature, running away isn’t an option—facing problems head-on is the only way.”(B4)

“I’ve been teaching for 8 years, and it was only in the 7th and 6th years that I started winning awards, while in research, I had good results in 3 years.”(A1)

This reflects their distinctive challenge appraisal tendency [56], systematically reframing pedagogical difficulties as catalysts for professional growth rather than existential threats. When confronting inevitable adversities, participants demonstrated adaptive meaning-making, prioritizing process-oriented fulfillment over outcome dependency, as exemplified by:

“I regret nothing, even in failure.”(A6)

4.1.2. Transdisciplinary Pedagogical Literacy

The transdisciplinary literacy grounded in disciplinary expertise constitutes the fundamental competence layer of expert teachers. Expert teachers demonstrate a distinctive disciplinary cognitive schema. Vertically, they master knowledge trajectories spanning from undergraduate fundamentals to cutting-edge disciplinary frontiers, while proactively anticipating field evolution to adapt curricula:

“In broad domains, scholars from Discipline A and B often struggle to communicate. Yet these fields develop within shared frameworks and will inevitably converge. My mission is to train students who can bridge A and B—if we don’t lead this effort, others will.”(A5)

Horizontally, they exhibit conscious cross-disciplinary networking capabilities:

“The ‘Motion Control’ course serves electromechanical systems’ operational efficacy… integrating electrical engineering, advanced mathematics, and automatic control theory. This demands preparation across multiple domains.”(A5)

Their adaptive curricular redesign customizes content to meet a variety of professional needs.

“While our engineering program adopts mathematics department courses, I strategically streamline content—emphasizing conceptual architectures over rote knowledge.”(A5)

4.1.3. Transformative Instructional Praxis

Transformative Instructional Praxis constitutes another essential element within the Fundamental Competence Layer of expert teachers. The teaching experts demonstrate a distinct structural pattern. They conceptualize pedagogy as moral mentorship that cultivates practical wisdom, moving beyond mere content delivery. Those practice reflects the Chinese educational philosophy of “teaching knowledge while nurturing character”, bridging Western and Eastern pedagogical paradigms.

“Teaching must transcend knowledge transmission to cultivate moral reasoning and practical wisdom.”(B5)

Regarding knowledge delivery, the internalization of disciplinary knowledge enables textbook-independent, context-responsive teaching, exemplifying Berliner’s concept of “flexible expertise.” [19]

“I can teach without textbooks, for they are all in my mind.”(A6)

Differentiated instruction strategies were consistently observed, putting into practice the educational principle of teaching students based on their individual aptitudes. Additionally, real-time instructional adjustments were adopted as a form of adaptive decision-making.

“During class this afternoon, I observed that the students were distracted; consequently, I incorporated interactive questions to engage their attention.”(A1)

The analysis further uncovered unique approaches in learning assessment, reflecting process-oriented evaluation that enhances learning outcomes.

“It is essential to comprehend the reasons behind students’ preference for Option A, rather than merely assessing its correctness, as Option A may be generated by AI.”(A5)

Transformative Innovation Capacity is manifested through interdisciplinary teaching and technology integration.

“Interdisciplinary programs require hybridized teaching materials.”(A4)

“Continuously learning AI and experimenting with AI-enhanced teaching.”(B4)

Crucially, synergistic relationships exist among these competencies: technological integration creates new possibilities for knowledge delivery, while strong foundational teaching skills ensure the quality of innovative practices. These findings provide empirical evidence for understanding expert teachers’ professional development trajectories.

4.1.4. Scholarship of Integrated Application

The Scholarship of Integrated Application constitutes the advanced competence of expert teachers, demonstrating the development of pedagogical scholarship and its broader impact. Expert teachers in teaching consistently demonstrate the professional capacity to transfer their disciplinary research competencies to the field of educational inquiry. When confronting pedagogical challenges, they exhibit a pronounced theoretical consciousness.

“Whether in humanities, natural sciences, or social sciences, we must investigate the fundamental principles underlying education.”(B5)

This research orientation displays distinct disciplinary characteristics. For instance, humanities and social science teachers emphasize the affective dimensions of teaching, while STEM teachers track technological impacts on education.

“Utilizing technological tools to authentically capture students’ emotional and cognitive engagement.”(B2, humanities and social science)

“I have always been quite worried about how AI technology is growing. For example, I read a report in 2018 on how AI influences education.”(A5, engineering)

Upon achieving research outcomes, they actively disseminate findings through scholarly publications, demonstrating scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) capabilities, while systematically applying research insights to enhance teaching practice—a cyclical process embodying evidence-based pedagogical refinement.

4.1.5. Sustainable Educational Leadership

Sustainable Educational Leadership constitutes the outermost layer of the expert teacher characteristic model, demonstrating its ecosystemic influence. Expert teachers in teaching demonstrate marked sustainable development traits and professional leadership characteristics, manifested across key dimensions. Initially, they exhibit the ability for self-iteration and proactive technological adaptation, integrating openness with pragmatic discernment.

“Pushing beyond prescribed competency standards is necessary for breakthrough growth.”(B3)

Secondly, the analysis identifies three leadership pathways related to organizational leadership impact.

- Exemplary leadership. Individuals intentionally take on the role of professional role models and recognize that their influence extends beyond merely disseminating knowledge to also shaping ethical and professional development.

“The value guidance of teachers is more important than knowledge transmission.”(A5)

- 2.

- Collaborative Resource Integration. Teachers encompass understanding resource allocation logic, recognizing stakeholder processes, and facilitating strategic communication.

“Understanding administrative rationale ensures project success. Additionally, you need to be able to say things clearly and concisely in the shortest amount of time.“(B5)

- 3.

- Educational Ecosystem Construction. Visionary practitioners transcend classroom boundaries to architect learning ecosystems, recognizing education as a complex adaptive system requiring multi-stakeholder coordination.

“Education is a governance system requiring synergistic coordination.”(A5)

Critically, these competencies exhibit dynamic synergy: lifelong learning scaffolds organizational influence, while leadership experiences reciprocally fuel developmental needs. Narrative data reveals an evolutionary trajectory: “self-breakthrough → professional modeling → ecosystem optimization”—a progression shaped by both institutional contexts and agential professionalism.

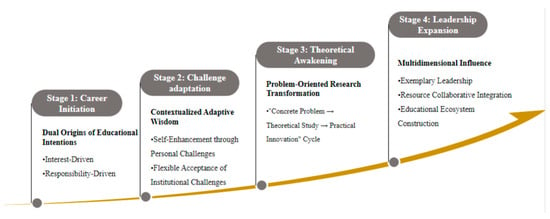

4.2. Professional Growth Path

The professional development of teaching experts in research-intensive universities demonstrates a distinctive evolutionary pathway, comprising four key phases (see Figure 2):

Figure 2.

The growth path of expert teachers in teaching.

4.2.1. Stage 1: Career Initiation—Dual Origins of Educational Intentions

Research has found that there are two typical patterns for teachers’ professional development starting points:

- Interest-driven: Some teachers develop intrinsic drive through early teaching experiences. As a teacher echoed:

“When I began teaching labs during my PhD, I found immense fulfillment in helping students grasp concepts I’d mastered.”(A6)

For these educators, teaching constitutes their professional core value, with positive student feedback serving as key sustaining motivation.

- Responsibility-driven: More teachers initially engage with teaching due to professional duty or external expectations. As a teacher noted:

“Any conscientious teacher would self-reflect upon hearing ‘this class is a waste of time.’”(A4)

Notably, accumulating teaching experience often transforms the latter into the former, fostering a more stable and internalized professional identity.

4.2.2. Stage 2: Challenge Adaptation—Contextualized Adaptive Wisdom

When teachers enter the professional growth stage, they often face various challenges, including the uncertainty between teaching effort and outcomes.

“It’s normal to put in effort without getting appreciation in teaching—getting both is just luck.”(A4)

Another challenge is the lack of collaborative support in teaching.

“You might be the only one teaching this course, with no one to guide you on how to approach a specific topic. You have to reflect on your own, iterate independently, and find materials by yourself.”(A3)

Then, the imbalance in teaching performance evaluation.

“You can’t achieve high performance solely through teaching. Research funding and projects come with clear bonus points, but how much can teaching contribute? Very little.”(B5)

Additionally, the insufficient support for teaching development resources.

“There are far too few opportunities and resources allocated for teaching.”(B3)

Together, these issues form the structural challenges that expert teachers in teaching must confront. In response to these challenges, teachers have developed differentiated coping strategies. They view challenges tied to personal ability as solvable rather than insurmountable: Technical obstacles are categorized as “something you can master if you’re willing to learn” (B5). Teaching process hurdles are seen as “solvable manual work” (A5). The struggle over time and energy is framed as a phased problem.

“If I had focused my energy on research, I might not have performed worse than others! Last year, my annual evaluation score was near the top of the department’s benchmark.”(A6)

As for systemic constraints, they reconcile with the situation and adopt a non-confrontational acceptance.

“You can’t change this—the broader environment is just like that. Can you escape it?… Escaping is useless, complaining is useless—you can only face it and deal with it.”(B3)

4.2.3. Stage 3: Theoretical Awakening—Research–Practice Integration

As their professional development deepens, teachers invariably enter a stage of theoretical awareness. When practical experience fails to resolve teaching challenges, they begin turning to systematic educational theory research. As a teacher stated:

“In education, we must explore the underlying pedagogical principles of every discipline.”(B5)

Teacher A5 started studying papers on AI and education as early as 2018, attempting to integrate AI into teaching. And teacher B3 published three papers on educational reform during the COVID-19 pandemic, sharing findings for peer reference while also refining their own teaching practices.

A notable finding reveals disciplinary-specific problem-solving approaches, where faculty from distinct academic domains employ divergent yet equally valid methodological pathways when addressing identical pedagogical challenges. This phenomenon illustrates the disciplinary embeddedness of teaching practices while demonstrating unexpected convergences in ultimate educational objectives.

“Mathematics for engineering students should be taught in conjunction with real-world engineering applications. Learning purely within a theoretical science framework, detached from practical scenarios, renders it ineffective.”(A4, engineering)

“Designing courses that integrate science curricula with problem-solving in specific engineering fields.”(A3, pure science)

This research shift exhibits a cyclical pattern of “concrete problem → theoretical study → practical innovation,” which, at its core, follows the professional growth logic of developing to solve problems. Such theoretical consciousness becomes a defining trait of expert teachers in teaching.

4.2.4. Stage 4: Leadership Expansion—Multidimensional Influence

During the professional maturation stage, teachers’ influence begins to transcend the individual level, entering a phase characterized by leadership and radiative impact. They inspire both students and fellow educators through value-driven demonstration, collaborate with various departments to promote resource integration, and strive to construct an educational ecosystem that fosters systemic optimization and innovation.

The emergence of such leadership signifies the transformation of expert teachers from “skilled practitioners” into “educational leaders,” with their influence expanding beyond classroom instruction to encompass the improvement and innovation of the entire educational system.

In summary, this four-stage developmental path not only reflects the inherent logic of expert teachers’ professional growth but also embodies the unique institutional demands of research-oriented universities. Compared to teachers in basic education, expert teachers in research-intensive universities encounter the tension between academic culture and teaching expectations at an earlier stage. Their professional development is marked by a stronger problem-solving orientation and more systematic theoretical reflection, ultimately culminating in a broader and more far-reaching professional influence. This growth model holds significant implications for understanding the dynamics of faculty development in higher education and for refining teacher support systems.

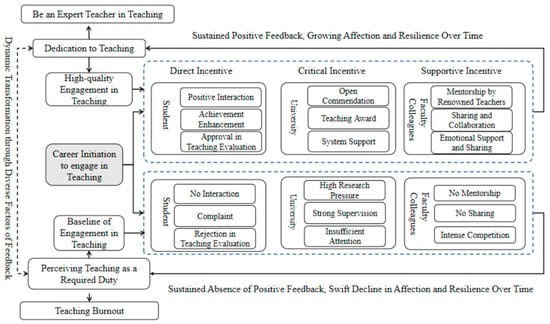

4.3. Motivation and Mechanisms

Educational passion serves as the core driving force that compels teachers to face challenges and commit to high-quality teaching. As Teacher A8 noted, it involves a genuine liking, loving, and voluntary dedication to the profession. When teachers perceive teaching as a cherished vocation, they naturally engage in innovative instructional approaches. In contrast, if they see it merely as an obligatory professional duty, they tend to exert only the minimum effort required.

Both teaching enthusiasm and professional resilience are dynamic psychological traits that fluctuate in response to external feedback. When passion reaches a critical threshold, it evolves into enduring devotion, while prolonged depletion can reduce teaching to a mechanical task. The crucial factor is whether teachers receive positive external reinforcement before their passion is completely drained.

External feedback influences teaching commitment through three primary dimensions: First, positive evaluations and learning outcomes from students provide the most immediate and motivating form of encouragement. Second, institutional recognition of teachers’ pedagogical contributions offers essential organizational support. Third, professional collaboration within teacher communities provides vital sustenance during periods of burnout, aiding educators in overcoming developmental plateaus.

This multidimensional, visible support system effectively sustains teachers’ psychological resilience, allowing them to break through obstacles and ultimately establish a virtuous cycle where external motivation and internal professional identity reinforce one another. Consequently, this research has developed a Teaching Incentive Model for research-intensive university faculty, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Teaching Incentive Model for Research University Faculty.

5. Discussion

5.1. Beyond Traditional Paradigms: Theorizing the Characteristics and Developmental Trajectories of Expert Teachers

5.1.1. Characteristics of Expert Teachers in Higher Education

This study found that the core difference between expert teachers in research universities and those in basic education lies in their interdisciplinary capabilities based on their disciplinary knowledge systems. This is manifested in teachers’ ability to overview their disciplinary knowledge systems and integrate multidisciplinary content. For example, when teaching the same course to different majors, they adjust teaching content to align with professional characteristics. They develop typical interdisciplinary courses. This finding responds to the “Pedagogical Content Knowledge” (PCK) theory proposed by Shulman et al. [57].

As senior expert teachers, they can even predict development trends in their own and related disciplines, and use these predictions to influence the curriculum system, teaching content, and teaching methods of their disciplines and programs. This aligns with the general consensus that “excellent research promotes teaching” [58] and demonstrates how research enhances teaching in research universities, as exemplified by MOOC pioneers who restructured course formats based on trends in internet technology development.

5.1.2. Teacher Development Stage Theory in Higher Education

This study proposes important supplements to traditional teacher development stage theories for higher education. Taking Berliner’s (1994) teacher development stage theory as an example [19], its linear “novice-to-expert” model is based on the relatively stable knowledge system of K-12 education, with the core indicator of stage transition being teachers’ mastery of fixed teaching content. However, higher education contexts present significantly different characteristic dimensions, including (1) cross-stage performance in content mastery: higher education teachers who should theoretically be at the “novice” stage in Berliner’s framework may directly demonstrate characteristics of the “competent” stage, such as actively selecting teaching content, distinguishing key from non-key points, and even critically evaluating textbooks. (2) Significant variations in teacher development stages caused by disciplinary and course-type differences. In higher education, some foundational theory courses (e.g., advanced mathematics) have stable knowledge systems, while cutting-edge field courses (e.g., new digital media) require continuous content updates. Differences in course nature may lead to variations in teaching proficiency among teachers with similar initial abilities and teaching commitments due to different allocations of effort, potentially rendering the original theory’s suggested timeframes for stage transitions (e.g., 2–3 years from novice to advanced beginner) ineffective.

When disciplinary and course-type differences render traditional teacher development stage theories partially invalid, exploring teacher development through differences in problem-solving depth presents a viable alternative. The “career initiation-difficulty adaptation-theoretical awareness-leadership expansion” trajectory revealed in this study emphasizes nonlinear professional transformation. At the “difficulty adaptation” stage, teachers encounter various teaching problems with hierarchical solutions: surface-level problems (operational aspects) can be addressed through repetitive teaching practice, while deep-level problems (theoretical aspects) trigger the need for educational theory research, marking the transition to the third stage. This finding echoes Boyer’s (1990) concept of “scholarship of teaching” while empirically demonstrating the concrete formation process of teaching scholarship capabilities [59]. The progression from the third to fourth stage represents a transformation from simple “classroom problem-solving” to “systemic influence,” with teaching experts’ leadership development exhibiting an expansion from classroom to educational system characteristics. This finding aligns with Harris’s (2005) description of distributed leadership theory [60]—‘collective leadership responsibility rather than top-down authority’—and is generally consistent with the research scope of Zhao and Cheng’s investigation of Chinese academic members’ leadership [61], revealing how the influence of teaching scholarship permeates from individual to organizational levels.

5.1.3. Disciplinary Sensitivity in Teacher Identity Formation

In the developmental process of teachers, higher education faculty must constantly negotiate their dual identities as researchers and educators. This study reveals a significant Disciplinary Proximity Effect in teacher identity formation. For disciplines with knowledge systems and research paradigms closely aligned with education science, such as linguistics, teaching, and research, form a “symbiotic cycle” where educational experiments generate new research questions. Teachers in these fields recognize teaching’s promotive effect on research and achieve better identity integration between researcher and educator roles.

Conversely, in disciplines with greater differences, such as biomedical sciences, undergraduate-level teaching of foundational content primarily consumes research time. Teachers in these fields experience greater conflict in constructing their professional identities. This finding provides a resolution to the debate initiated by Mathews et al. regarding teaching’s promotive effect on research [62]. Subsequent studies should examine this relationship through the lens of disciplinary research paradigms rather than making generalized judgments about the teaching-research nexus.

5.2. Implications for Teaching Practice: Meaning-Making and Resilience Development

The “research-centralism” ecology in research universities creates structural pressure on teaching. However, this study finds that expert teachers achieve teaching excellence under institutional constraints through meaning-making and adaptive strategy systems. This process reveals the intrinsic motivational mechanism for sustainable teaching development, providing important insights for teacher professional growth practices.

5.2.1. Meaning-Making: The Internal Drive of Teaching Mission

Expert teachers elevate teaching responsibility into moral commitment through educational narratives, forming the following practical pathways:

- Motivation enhancement: using self-accountability to counteract insufficient external incentives, viewing teaching as self-actualization rather than a task.

- Value reconstruction: balancing research-oriented evaluation bias with intrinsic interest, forming a “teaching long-termism” belief—valuing process experience over short-term outcomes, and reconciling with unchangeable institutional limitations.

This finding echoes Self-Determination Theory [63,64], indicating that teachers’ sustainable engagement in teaching self-development depends on self-satisfaction rather than relying solely on external rewards.

5.2.2. Emotional Resilience: A Key Factor in the Growth of Novice Teachers

For teachers who have not yet reached the expert stage, the construction of an emotional resilience system is crucial, with its core being the reframing of adversity cognition. For controllable problems (e.g., optimization of teaching methods), they could adopt strategies from expert teachers and address them with a growth mindset [65]. For uncontrollable problems (e.g., institutional constraints), they could employ a “realistic compromise-partial breakthrough” strategy, which involves accepting limitations while focusing on areas where personal influence is possible (e.g., innovation in a particular course).

This finding provides key design principles for teacher development programs, suggesting that, in addition to various programs targeting teaching skills, cognitive reframing training should be incorporated as a core component, such as offering mindfulness teaching workshops.

5.3. Policy Recommendations for Education: A Three-Tier Framework for Building a Sustainable Supportive Institutional Ecosystem

Amid calls for improving teaching quality and excellence in higher education, universities have increasingly attempted to implement supportive systems for teaching, with these efforts growing year by year. However, individual teachers’ perception of institutional support remains inadequate, as the inertia of the research-centered system continues to influence teaching engagement in multiple ways [66]. This study proposes the Teaching Incentive Model for Research University Faculty, positing that high-quality teaching engagement is closely linked to positive environmental feedback. Under institutional constraints, outstanding teachers may rely on personal capabilities to achieve localized breakthroughs. However, sustained institutional improvements are necessary to establish a sustainable educational ecosystem that encourages teaching, thereby fostering the professional development of more ordinary teachers. The construction of a university’s educational ecosystem should advance along these three dimensions:

- At the level of promoting positive student feedback, continuously construct a teaching-friendly environment that facilitates teacher-student interaction. This includes: expanding channels for teacher-student communication, optimizing formative assessment of learning, enriching students’ extracurricular activities and enhancing their impact on academic achievement, liberating students from the “GPA competition”, and helping them engage with and experience teaching in a freer state.

- At the level of institutional recognition for teachers’ efforts, it is necessary to reform the evaluation mechanism and establish a teaching support system that focuses on the process, is phased, and tiered. One of the institutions participating in this survey, advocated by the Center for Faculty Teaching Development, has initially established branch teaching development centers in various colleges. These branch centers are informal organizational structures, each with a director appointed from among the college’s teachers who possess teaching experience, achievements, and a passion for teaching, with support from college management. They are responsible for enhancing the disciplinary teaching capabilities of all faculty in the college. Unsolved teaching problems are then reported to the Center for Faculty Teaching Development, which seeks out expert teachers and education professionals to provide solutions. This can be regarded as a preliminary attempt at institutional reform to recognize teachers’ efforts. Teaching workload is recognized for branch center directors and core team members and included in annual performance evaluations. In contrast, another surveyed institution without this system has shown lower quantity and stability in provincial/ministerial-level teaching honors compared to the former institution. The former institution has teachers winning national-level teaching awards annually, while the latter cannot consistently achieve honors at the same level each year, serving as supporting evidence.

This study contends that the journey from teachers’ engagement in teaching to earning school-level and provincial/ministerial-level honors that count toward performance evaluations and promotion systems is long and arduous. Ordinary teachers can hardly sustain this process independently and require support along the way. Phased encouragement from the institution and environment is essential support for cultivating excellent expert teachers. Tailored support plans should be developed for different teacher groups, forming a full-cycle development pathway covering novice teachers (guidance programs), mid-career teachers (capability enhancement), and senior teachers (digital transformation).

- 3.

- Regarding the construction of teacher communities for peer support, there is an urgent need to break through the limitations of traditional departmental organizational structures and establish new types of cross-disciplinary collaborative learning communities.

Currently, university organizations operate based on colleges and disciplines. Nearly all surveyed institutions have mentoring systems where experienced teachers guide newcomers, which to some extent aligns with Kemmis’s theoretical framework of peer mentoring (including supervisory mentoring, supportive mentoring, and collaborative self-development mentoring) [67,68]. The disciplinary-based mentoring structures in surveyed institutions fall within these three types of peer mentoring proposed by Kemmis. However, practice shows that such single-discipline support mechanisms can no longer meet the demands of rapid knowledge updates in contemporary education. Particularly in new curriculum teaching, teachers commonly face the dilemma of “isolated lesson preparation,” lacking both professional guidance from senior teachers teaching the same course and constrained by the limited scope of help-seeking imposed by institutionalized pairing mechanisms. More notably, when new teachers fail to receive effective support during initial help-seeking attempts, they often abandon further requests due to interpersonal concerns. This not only results in low actual utilization rates of teacher support networks but also creates systemic deficiencies in emotional support. This situation compels us to reconsider the potential value of Kemmis’s proposed cross-institutional peer collaboration networks [69], which may offer a new pathway transcending the complexities of intra-disciplinary interpersonal relationships.

Research findings reveal that disciplinary conflicts emerging in current teaching practices, such as debates over “whether engineering mathematics courses should be taught by engineering or science faculty,” while superficially appearing as disputes over teaching authority, actually reflect deeper ecological issues in education—how to better adapt theoretical teaching to applied talent cultivation needs. Drawing on Capra’s ecosystem theory, such conflicts precisely reveal potential connections between elements within the same educational system [70]. From the perspective of constructing educational ecosystems, these surface-level interdisciplinary conflicts fundamentally stem from missing communication channels. Establishing cross-disciplinary collaboration mechanisms can not only resolve oppositions but also creatively address teaching adaptability issues. This understanding highly aligns with the fundamental principles of ecosystem construction [71] and provides important insights for reconstructing teacher professional development support systems: only by breaking down disciplinary barriers and building open, interconnected teacher learning communities can we truly achieve continuous improvement in teaching quality and the healthy development of educational ecosystems.

6. Conclusions

This study employs grounded theory methodology to systematically investigate the typical characteristics, developmental trajectories, and key driving forces of expert teaching faculty in research universities under asymmetric incentive systems. Expert teaching faculty in research universities are educators who integrate Educational Passion and Professional Belief, Disciplinary Expertise, Pedagogical Wisdom, Educational Research Capability, and sustainability and Leadership. Their development follows a “career initiation-difficulty adaptation-theoretical awareness-leadership influence” trajectory, with variations in each stage’s content depending on their discipline and course types. Facing insufficient institutional incentives, these teaching experts establish an interactive system of “high-quality teaching engagement–external positive feedback” to sustain their professional dedication.

Higher education institutions should focus on constructing comprehensive support systems to promote sustainable faculty development: at the institutional level, reforming evaluation mechanisms to establish process-oriented, phased, and tiered teaching support systems; at the student level, continuously developing teaching environments that facilitate teacher-student interaction; at the peer level, building teaching development communities that foster interdisciplinary exchange. This multidimensional, interconnected support system can effectively maintain teachers’ psychological resilience, help them overcome developmental bottlenecks, and ultimately achieve a virtuous cycle from external motivation to internal professional identity.

This study has the following limitations that need to be acknowledged: First, regarding research samples, since the data were collected from only two “Double First-Class” initiative universities, while ensuring the homogeneity of research subjects, it fails to adequately reflect the diversity characteristics of the higher education system. Particularly, the exploration of organizational environment differences among various types of universities and their impacts on teachers’ professional development remains insufficient. Second, as a key feature distinguishing higher education from basic education, the influence of disciplinary cultural differences on teachers’ developmental pathways has not been thoroughly analyzed in this study, which, to some extent, limits the differentiated understanding of growth mechanisms for teachers across different disciplines. Based on these limitations, follow-up research will focus on expanding the investigation scope by: increasing institutional type samples (e.g., application-oriented universities, industry-characteristic universities, etc.); broadening disciplinary coverage; and employing mixed-methods research combining quantitative and qualitative approaches. The study will particularly examine the influence mechanisms of organizational environment characteristics and disciplinary cultural differences on the growth of outstanding teachers, with the aim of establishing a more explanatory theoretical model of teacher development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.H.; methodology, Y.H. and L.J.; software and validation, Y.H., L.J. and R.Z.; formal analysis, Y.H.; investigation, Y.H.; resources, Y.H. and L.J.; data curation, L.J. and R.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.H.; writing—review and editing, Y.H., L.J. and R.Z.; visualization, L.J. and R.Z.; supervision, L.J.; project administration, Y.H.; funding acquisition, Y.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the National Social Science Fund of China, General Project in Education “Research on Modeling and Improvement Mechanisms of Blended Teaching for College Teachers Based on User Portraits” (Grant No. BCA200086).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Center for Teaching and Learning Development, China Agricultural University. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The participants in our study’s survey are acknowledged, and we appreciate all the researchers who helped with data gathering and processing. We also appreciate the reviewers who offered us their insightful criticism to support the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ministry of Education of China. Several Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of High-Quality Undergraduate Education and Comprehensively Improving Talent Training Capabilities [Policy Document]. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A08/s7056/201810/t20181017_351887.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Ministry of Education of China. Implementation Plan for Undergraduate Education Teaching Audit and Evaluation in Regular Higher Education Institutions (2021–2025) [Policy Document]. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A11/s7057/202102/t20210205_512709.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- State Council of China & Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. Opinions on Promoting the Spirit of Educators and Strengthening the Construction of High-Quality Professional Teaching Teams in the New Era [Policy Document]. Available online: https://english.www.gov.cn/policies/policywatch/202410/23/content_WS67185735c6d0868f4e8ec31d.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Zhao, J.M. The Unbalanced Balance: A study of the Issue of “Overemphasizing Research and Devaluing Teaching in Faculty Performance Evaluation—Studies of the SC Undergraduate Education Reform in the USA (8). Res. High. Educ. Eng. 2020, 68, 6–27+44. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBa-MIIPgR_Ga1AZOekeWOKHzIw07pfzB9K2kp_Dhw4CEpBEhXvbqdzDPQGDgPFQ8fqo8dJxb6srn-OcXw9Eh5qKO1I8hDVV3U_K8k7U4iXVb29DEyf6T9uTDMLfET2XlzzIUOhg9Sx7CBBqBocBqu40o3JKWghsD73k5WLNlgQf6Q==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Bull, S.; Cooper, A.; Laidlaw, A.; Milne, L.; Parr, S. You certainly don’t get promoted for just teaching: Experiences of education-focused academics in research-intensive universities. Stud. High. Educ. 2024, 50, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angervall, P.; Baldwin, R.; Beach, D. Research or teaching? Contradictory demands on Swedish teacher educators and the consequences for the quality of teacher education. J. Prax. High. Educ. 2020, 2, 63–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European University Association. Promoting a European Dimension to Teaching Enhancement: Feasibility Study from the European Forum for Enhanced Collaboration in Teaching (EFFECT) Project. EUA Publications 2019. Available online: https://eua.eu/ (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Huang, Y.F.; Ma, X.L.; Jiang, K. Can Good Researchers Become Good Teachers: An Empirical Research Analysis Based on a National Survey of Undergraduate College and University Teachers. China High. Educ. Res. 2024, 40, 58–64. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBbGyT1dLkNjuNPdL0jA-roiJdmDZCksfzYx3Zup6c9tk4DTjQczbrPckPM-zboYJy9F2u11vdP7KXhj6lvclIB7nCuKsZF1irgJZFGjkSpDSJSWplOz3Knexx4P8_K8RiOhgP21_v4q_kaaUUq-oZpnz7tNRsS6V-Q=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Ministry of Education of China. Several Opinions of the Ministry of Education on Comprehensively Improving the Higher Education Quality 2015. Available online: http://www.moe.gov.cn/jyb_xxgk/moe_1777/moe_1778/201511/t20151105_217823.html (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Ministry of Education of China. Coordinate Development of World-Class Universities and First-Class Disciplines Construction Overall Plan 2017. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-01/27/content_5163903.htm (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- China Association of Higher Education. Analysis Report of National Teaching Competitions for University Faculty (2012–2020) [Policy Report]. Available online: https://www.cahe.edu.cn/site/content/14039.html (accessed on 4 June 2025).

- Sternberg, R.J.; Horvath, J.A. A Prototype View of Expert Teaching. Educ. Res. 1995, 24, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.L. A study on teaching efficacy and instructional monitoring ability of expert-novice teachers. Psychol. Sci. 2000, 23, 741–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.J. Research on the Teaching Scholarship Ability of Outstanding Teachers in Colleges and Universities Based on Grounded Theory. High. Educ. Explor. 2021, 57–64. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBZhpi9wZOjjYfiKhYTv5Io2qwfiJplGyutZ7JBbwGzlW72npua6R2PSyJl6k5CrIDwIaAIxMpA3jXOp8b40lUqCjuIfrI7M4rPpGvv5qBU7v7kat-G1nrpAUKv1oswBFO81ezjMP7FlGkkWypLY_AyRX9wSf5VyYArynrkal3jHYA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Boshuizen, H.P.A.; Gruber, H.; Strasser, J. Knowledge restructuring through case processing: The key to generalise expertise development theory across domains? Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 29, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, C.E.; Jarodzka, H.; Boshuizen, H.P.A. Classroom management scripts: A theoretical model contrasting expert and novice teachers’ knowledge and awareness of classroom events. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2021, 33, 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M. Teachers’ Flower Book: Growth of Expert Teachers; Chen, J., Translator; East China Normal University Press: Shanghai, China, 2016; pp. 33, 50, 54. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson, K.A.; Hoffman, R.R.; Kozbelt, A.; Williams, A.M. (Eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018; pp. 2–6. [Google Scholar]

- Berliner, D.C. The Development of Expertise in Pedagogy; American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, E.E.; van Tartwijk, J.; van der Schaaf, M.F.; Kluijtmans, M. What makes an expert university teacher? A systematic review and synthesis of frameworks for teacher expertise in higher education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, R. A comparative research on the mental character of novice, proficient and expert teachers. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2004, 36, 44–55. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBYCDadXKqP50DLQ0VBzK3FAFNyJT3h25AfYZyVGIexCcfnQiwuQPr0xp_5_Nuw0Zj5_itcZozvqPBrw12hTYaMSBWr6v2pSJHv_P5G-TJHq_I6vvVZcRKpXYXJwb6VTH2sjX5HG-RhJifDYzWTxaT8yW9imBxc5FxWKSLn22knmXA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Chen, J.J.; Xu, Y.S.; Tan, Y. Ideal Indicators, Development Stages, and Critical Motivation of Expert Teachers—Model Construction based on Grounded Theory. Teach. Educ. Res. 2024, 36, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Shen, J. The Teaching Philosophy of Excellent University Teachers. High. Educ. Explor. 2021, 63–69. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBapufqHwi1lzD1ulc5M1r9L6TvUInNfobWk7nPRo80dsLAGbBScmHVAJ6m2GlY90dJ9zEnuYU66Vtv13TMMRVRXvVzCHRcB2soIRUNAt5dMZ_y0Zuqty9dYv5bwrQ1d0adJQARlA0EHVzU60ICixNBbAzd7c83I3FEfS88X63Kr-Q==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Ferrero, L.G.P.; Salles-Filho, S.L.M. Planning and resource allocation models in research-intensive universities: Budget allocation and the search for excellence. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research England. Research Excellence Framework: How Research England Supports Research Excellence; UK Research and Innovation: Swindon, UK, 2025; Available online: https://www.ukri.org/who-we-are/research-england/research-excellence/research-excellence-framework/#contents-list (accessed on 8 June 2025).

- Geuna, A.; Piolatto, M. Research assessment in the UK and Italy: Costly and difficult, but probably worth it (at least for a while). Res. Policy 2016, 45, 260–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Excellence Framework. Director’s Report. REF 2021. Available online: https://2021.ref.ac.uk/media/1918/ref-directors-report.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Morgan Jones, M.; Manville, C.; Chataway, J. Learning from the UK’s research impact assessment exercise: A case study of a retrospective impact assessment exercise and questions for the future. J. Technol. Transf. 2022, 47, 722–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, D. Performance-based university research funding systems. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkers, K.; Zacharewicz, T. Research Performance Based Funding Systems: A Comparative Assessment; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W. How Research University Funding Allocation Enhances Academic Output: Analysis of Direct and Mediating Effects Based on Panel Data of HEIs Directly under the Ministry of Education from 2007 to 2018. Fudan Educ. Forum 2023, 21, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Chen, Y.; Sun, Y.; Tong, Y.; Liu, L. The measurement, level, and influence of resource allocation efficiency in universities: Empirical evidence from 13 “double first class” universities in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanassoulis, E.; Sotiros, D.; Koronakos, G.; Despotis, D. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of university academic recruitment and promotion policies. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2018, 264, 742–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Wall, T.; Salvia, A.L.; Frankenberger, F.; Hindley, A.; Mifsud, M.; Brandli, L.; Will, M. Trends in scientific publishing on sustainability in higher education. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.C. An Analysis of High-Level Universities Faculty Members’ Undergraduate Teaching Investment and its Influencing Factors. China High. Educ. Res. 2018, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.W. Causes and countermeasures of the “involution dilemma” of young university teachers. People’s Trib. 2022, 92–95. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=9IId9Ku_yBaxYdKclxXQdFe44Eag-iDmFDZF9WRPG_DhVuHNbcUkiGfmnQI0b4hZTN7Rcuz5BpVxmQ00HraLdb4sxBGHmDcXCETyy3iCEWtjzWPqWL20OmqFN_4NDIi6dTyulN1pFyFnQ4uHUcrG2TLAI0d_yfGVjAHraWic5ZY3bWH6j3zjpw==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Mo, S.Z. A Study on Academic Involution and Counter-Involution Strategies Among Young University Faculty from a Grounded Theory Perspective. Renmin Univ. China Educ. J. 2025, 1–23. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/11.5978.G4.20250325.1031.002 (accessed on 19 June 2025).

- Borg, S.; Liu, Y. Chinese college English teachers’ research engagement. Tesol Q. 2013, 47, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kálmán, O.; Tynjälä, P.; Skaniakos, T. Patterns of university teachers’ approaches to teaching, professional development and perceived departmental cultures. Teach. High. Educ. 2020, 25, 595–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geschwind, L.; Broström, A. Managing the teaching–research nexus: Ideals and practice in research-oriented universities. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2015, 34, 60–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.P.; Tang, Z.; Lü, S. What Influences Chinese University Faculty’ Teaching Engagement:a HLM Analysis Based on Personal and Environmental Factors. Res. Educ. Dev. 2022, 42, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]