Abstract

The level of participation and performance of water user associations (WUAs) in drained and irrigated areas is influenced by many factors. This paper aims to identify the main challenges to the functioning and performance of these associations in Poland and Ukraine using the methodology of international comparative analysis. We examined legal, organizational, and financial framework of WUAs performance in Poland and Ukraine based on selected case study areas. The results of the study indicate that creation of WUAs in both countries can be assessed as beneficial for sustainable water development in general. However, it is found that the actions intended to bring benefits can actually exacerbate the problem of drought and water shortages. Research shows that the lack of complete documentation on the layout of the drainage networks plays a huge constraint factor that can lead to problems with controlling the reconstruction of drainage networks and significant deterioration of water relations. Another significant problem is the restriction of the scope of WUA activities in Poland to those types of actions subsidized by the state, while lacking financial resources for other necessary activities.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, global ecological threats on Earth have been intensifying, including climate change, desertification, and loss of biodiversity, which are destroying natural ecosystems and posing a danger to humanity’s existence [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. Desertification is one of the most alarming global processes of environmental degradation that is also becoming a growing threat in Europe [8,9,10,11]. In areas prone to desertification, the physical properties of soils deteriorate, vegetation declines, water pollution increases, land productivity sharply declines, and the ecosystem’s ability to self-recover diminishes, resulting in a complex socio-environmental problem, which requires long-term efforts and effective multilevel collaboration arrangements to combat [12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

In Ukraine, these threats are no less dangerous, especially when it comes to climate change, which manifests itself in severe droughts. In recent years, global warming has begun to have a negative impact on the cultivation of agricultural crops. Due to excessive drought, cultivating agricultural crops in the steppe and south forest-steppe regions of Ukraine without irrigation has become almost impossible, and this negatively affects land productivity and agricultural production yields. Due to changes in the global climate, approximately two-thirds of Ukraine’s territory is in a risky zone for agriculture.

By the statistical data as of 1 January 2021, that is, before the beginning of the Russo-Ukrainian War, 5.48 million hectares of reclaimed land were accounted for in Ukraine, including 2.17 million hectares of irrigated and 3.3 million hectares of drained land with the appropriate reclamation infrastructure [21].

The effects of climate change are significant for agricultural production in Poland as well. Extreme weather events, floods and agricultural droughts in particular, are becoming more frequent, posing risks to crops and infrastructure. Increased temperatures and altered precipitation patterns are causing changes in crop suitability, potentially reducing yields of some crops [22]. The sector is facing the necessity to conduct adaptation measures to the climate change taking place [23,24,25]. One of the elements of adaptation measures, especially from the agricultural point of view, is the problem of water [26,27].

Water is an essential component of human life, and as a renewable, its single source and presence can only be regulated by nature. People can only control aspects such as access, preservation, and distribution of water between different users. However, human influence can significantly reduce water flows due to poor management and use of land resources, lack of knowledge about agriculture, including land reclamation and irrigation of crops, as well as inefficient use of management skills and distribution of water [28].

Reliable access to water remains a major constraint for millions of poor farmers, mostly those in rainfed areas, but also those involved in irrigated agriculture. Climate change and the resulting changing rainfall patterns pose a threat to many more farmers, who risk losing water security and slipping back into the poverty trap [29].

Water user associations (WUAs) operate in a large number of countries across the world on different legal and organizational principles enabling farmers to play a greater role in managing irrigation and drainage water [30,31,32,33]. In Eastern European countries, WUAs were usually established on the basis of existing legislation as companies, cooperatives, and different types of civil association or non-government organizations [34].

WUAs bring together land users. Their development and strengthening made the farmers capable to jointly manage their land. Almost all members of WUAs are small-scale farmers. WUAs support small-scale farming systems, guarantee gender justice in relations to land, and ensure transparency and accountability and inclusive decision-making processes over land. At the same time, WUAs also make the evaluation of the social and environmental impact of agriculture possible. In the longer term, this ensures a sustainable ecosystem management.

The level of participation and performance of WUAs in drained and irrigated areas is influenced by many factors. WUAs face obstacles of inadequate funding, lack of revenue, and technical capacity [35]. The literature on the subject discusses a number of factors hindering WUAs performance: (i) internal (pertaining to the community of users and management factors) such as infrastructural problems, operational hazards, and corruption, failing in water equity or lack of community engagement, (ii) as well as external (political, socioeconomic, and physical) such as political interference, ineffective policies, and rigid water bureaucracies [36,37,38,39,40,41]. According to [34], the absence of appropriate legislation negatively impacts WUAs sustainability, even if it permits their formal establishment. Some case studies [42] indicated that WUAs do not show overall superiority in almost all aspects in terms of improving irrigation management performance compared with traditional management institutions. However, there is a noticeable shortage of case study research addressing both constraints to WUA functioning and propositions of potential solutions and actionable steps.

Moreover, in terms of WUAs’ performance assessment, existing research provides numerous examples of increased irrigation and drainage sustainability and proves positive overall impact of WUA functioning on water management [43,44,45]. According to [46,47,48,49,50], the role of WUAs has emerged as prominent for sustainable water use in irrigated agriculture on a global scale. According to [51], WUAs are better than traditional management systems due to timeliness, maintenance expenditures, and fee collection. The literature on the subject indicates that high cooperation of farmers in the process of water management in an organized form such as WUAs is considered beneficial allowing to enhance long-term sustainability of irrigation and drainage systems, which are often very complex and affect land belonging to many owners. Proper maintenance of such systems requires organized, coordinated actions of all owners, which is very difficult to achieve taking into account unfavorable land ownership structure and varying degree of interest in maintaining the devices by individual owners.

Furthermore, the literature on the subject lacks scientific papers proving that WUA activities can lead to the deterioration of water relations. Our research shows that the WUAs’ actions, intended to bring benefits, can actually exacerbate the problem of drought and water shortages. Additionally, no research presenting comparative analyses on the WUA functioning in Poland and Ukraine was found.

This paper aims to investigate the history of and approaches to WUA functioning and organization in Poland and the Ukraine, and illustrates the influence of WUA activities on sustainable water management based on two case studies. Because of their mutual interest in climate adaptation measures concerning water management and governmental support for collaboration and exchange of experiences between Poland and the Ukraine, we examined legal, organizational, and financial framework of WUAs performance in both countries using the methodology of international comparative analysis. Furthermore, we qualitatively compared the extent to which activities performed by WUAs in drained and irrigated areas influence sustainable water management. We present one case study in each country seeking insight into the effectiveness of WUAs measures and to identify the main challenges to the functioning and performance of these associations in drained and irrigated areas.

2. Materials and Methods

The defined aim of the paper was achieved using the methodology of international comparative analysis [52,53]. International comparative studies may contribute to public policy research, since the understanding the distinct manners in which a certain issue may be tackled provides better comprehension of the problem itself as well as useful insights on the design of institutional responses [54].

Comparative analysis can be defined as a technique for identifying the type of elements that make up a whole based on their characteristics and assessing the efficiency of that whole against a set standard; the study of complex objects or phenomena means that comparative analysis can have many dimensions [55]. Comparisons consist of determining the presence or absence of the same qualitative features, the same or different varieties of qualitative features, and the same, similar, or different degrees of intensity of these same features occurring in different objects and phenomena [56]. Comparative analysis may vary depending on whether they aim to explain differences or similarities and the assumptions they make about the underlying causal patterns present [57].

International research and comparative analysis methods address many important issues and are conducted in various ways. In the simplest definitions, such research is considered to be based on data from at least two societies, countries, or that which crosses the borders of a single country [53,58]. These types of analyses are conducted in many different ways, using the following approaches [59]: (i) based on the assumption that countries differ from each other in certain features of interest to the researcher; (ii) those that attempt to identify and describe fundamental similarities between countries; and (iii) those in which the goal of the research is to determine the regularities governing the phenomena and processes in a given social issue.

Based on a review of definitions of the topic in the subject literature for the purposes of this study, it has been determined that the methodology of comparative analysis in international research involves the process of selecting research samples in different countries and conducting an analysis of the subjects and phenomena studied according to relevant criteria to determine the same, similar, or different levels of intensity of the characteristics being studied. The objective of this paper is to examine the legal, organizational, and financial framework of WUAs’ performance in Poland and Ukraine based on selected case study areas. We explore the presented problems using deductive reasoning. The research is qualitative in nature.

One of the key conditions to be met when conducting comparative analysis across different countries is having a comparable pool of information, which is not always easy. Therefore, for the purposes of this research, only written documents were accepted. Moreover, as data sources for assessing the performance of WUAs, we accepted only written documents and individual in-depth interviews with WUA chairmen. The following materials were used in the study:

- (1)

- Legal acts concerning creation and performance of WUAs in Poland and Ukraine;

- (2)

- Statuses of WUAs, statements of WUAs’ operations, and written notes taken during official WUA member meetings;

- (3)

- Cadastral data (including surveying, cartographic, and legal documentation concerning case study areas);

- (4)

- Other necessary data for achieving the objective including grey and scientific literature, and statistical data;

- (5)

- Results of individual in-depth interviews with chairmen of two case study WUAs.

The study was conducted in four stages using following research methods:

- Investigation of historical conditions for the development of irrigation and drainage systems and WUAs in Poland and Ukraine based on literature review, legal act analysis, and comparative analysis;

- Study of current challenges of water management in rural areas of Poland and Ukraine based on literature review, analysis and critique of the sources, the method of researching documents, and comparative analysis;

- Analysis of legal, organizational and financial peculiarities of WUAs creation and functioning in Poland and Ukraine, including inter alia principles of establishment, voluntariness, scope of duties and sources of funding based on legal act analysis, the method of researching documents, analysis and critique of the sources, and comparative analysis;

- Investigation of practical problems of WUA functioning and assessment of its performance based on selected case studies in both countries using the method of researching documents and individual in-depth interviews with chairmen of two case study WUAs.

Characteristics of the selected study areas and the reasoning for choosing them are included in subsections below. All available written documents concerning activities of case study of Kampinos (Poland) and Inhulets (Ukraine) were analyzed (including its surveying, cartographic, and legal documentation, statuses of WUAs, statements of WUAs’ operations, and written notes taken during official WUA member meetings). For better understanding and deepening the knowledge of practical problems of WUA functioning qualitative research method of individual in-depth interviews was used, in which the researcher conducts a conversation with a single respondent in order to explore their opinions, attitudes, and experiences. The method of individual in-depth interviews was chosen because of its flexibility and the possibility of asking questions and exploring threads that emerge during the conversation. The aim of the interviews was to understand the motivations and opinions of the respondent in the context of WUA management experience and obtain in-depth information on the technical state of meliorative system in the research areas. The respondents were asked following open-ended questions:

- When was the irrigation and drainage system built and what area does it cover?

- What were the effects of the construction of irrigation and drainage system?

- What is the current condition of the irrigation and drainage facilities?

- What is the scope of activities that are being currently carried out in terms of the maintenance of the irrigation and drainage system?

- What should be changed in the irrigation and drainage system and what would be the estimated costs of these activities?

- What in your opinion are the biggest challenges when it comes to WUA management in your area?

- What practical problems of WUA functioning do you face?

- What kind of problems and challenges do you foresee?

In addition, an analysis was carried out of several photos received from the WUAs’ chairmen, showing the results of work related to the maintenance of meliorative facilities, as well as maps showing the location of irrigation and drainage facilities. Voluntary participants were fully informed about the study’s purpose and procedures, and they were given the freedom to withdraw from the interview at any point.

To ensure conceptual, functional, and categorical equivalence in the research, the first phase involved a literature review to establish the nature and definition of WUAs in both countries. For the purposes of the study, a WUA in Poland should be understood as “water law companies” (WLCs). The legal institution of a water company is the only form under the currently applicable national law for property owners or other independent entities to participate in achieving the objectives and tasks of water management in Poland. When it comes to Ukraine, in accordance with the provisions of national law, there can be established “organizations of water users” (WUOs).

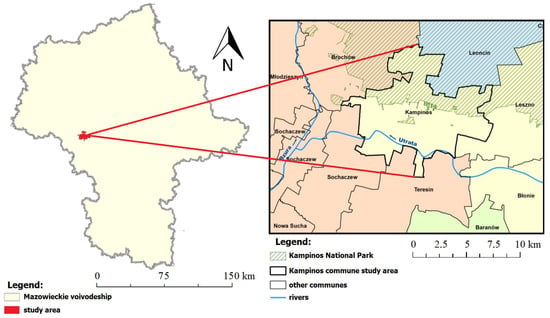

2.1. Mazowieckie Voivodeship—Characteristics of the Selected Study Area in Poland

In the case of the area of Poland, the implementation of the adopted study objective was carried out using the example of the WLC “Kampinos”, which operates in the rural commune of Kampinos located in the north-western part of the Masovian Voivodeship (Figure 1). Rural areas of the Masovian Voivodeship are characterized by some of the country’s largest water deficits during the growing season, consequently posing a threat of agricultural drought. In the Masovian Voivodeship, precipitation and water stored in the soil are insufficient to meet the water demands of plants. The Masovian Voivodeship features one of the largest areas of agricultural land in the country requiring reclamation measures—a total of 1204.8 thousand hectares [60]. Due to the uneven distribution of rainfall and the occurrence of both excessive and insufficient soil moisture, priority actions in water management in rural areas of the Masovian Voivodeship should be considered as mitigating the effects of climate change in water management, associated with increasing the natural retention capacities of watersheds and slowing down the water cycle in watersheds and reducing the effects of drought in agriculture [61].

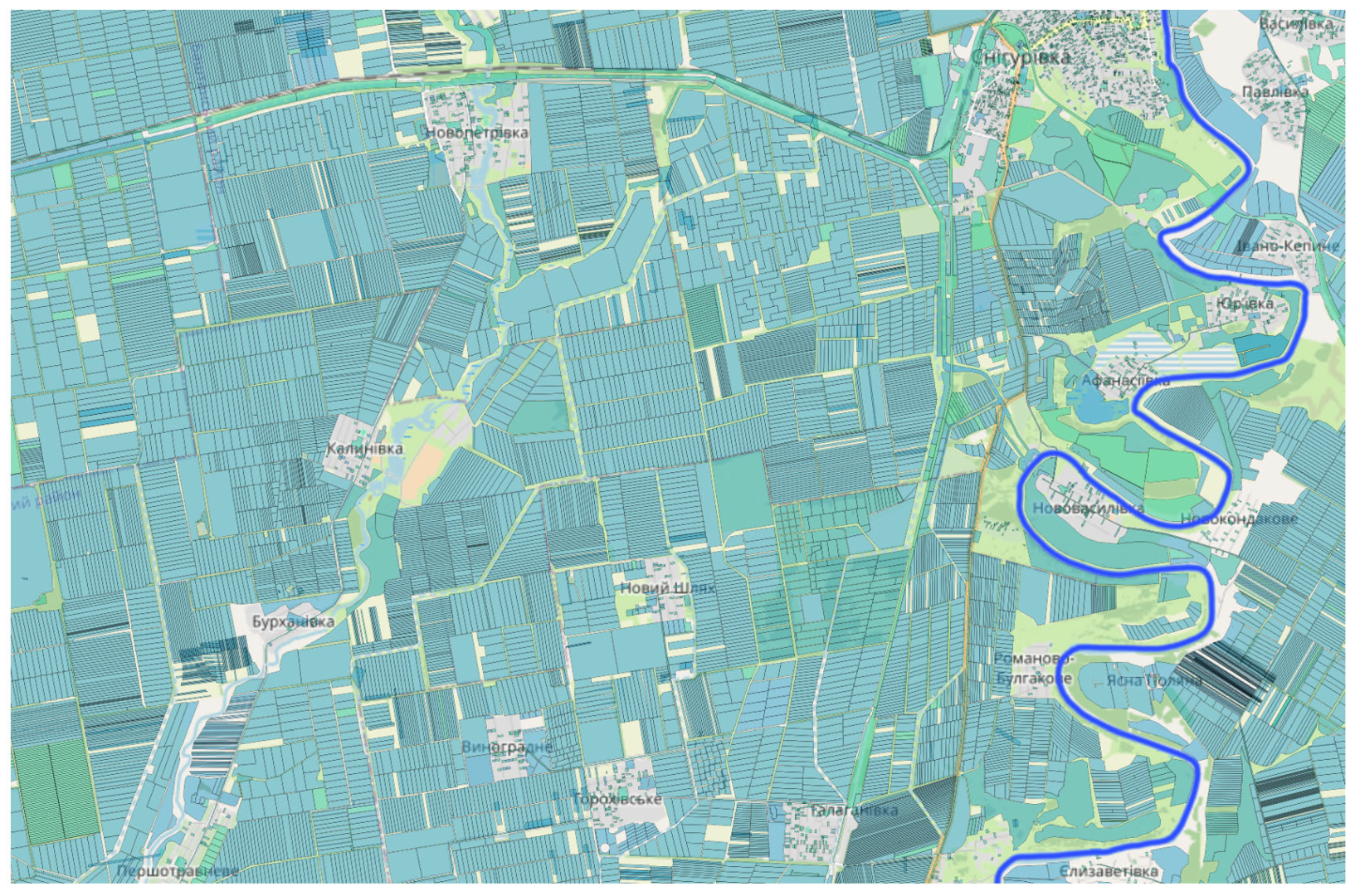

Figure 1.

Location of the study area in Poland. Source: Own study based on the Database of Topographic Objects and the State Register of Borders.

The total area of the Kampinos commune is approximately 84.5 km2. Nearly 39% of the commune’s area, or about 32.7 km2, mainly in the northern part, is occupied by the Kampinos National Park. The location of the Kampinos commune relative to neighboring communes and the borders of the Kampinos National Park is shown in Figure 2. Most of the land is agriculturally developed, with cultivated fields, orchards, and meadows dominating the landscape in the southern part, while forests prevail in the northern part. In the northern part of the commune, floodplain terraces characterized by meadows and wetlands, sandy over-flood terraces covered with forest, and numerous sandy dunes dominate. The remaining part of the commune has the character of a denudation plain, crisscrossed by streams that are tributaries of the longest river in Poland—the Vistula. It is characterized by a flat landscape and a relatively undiversified terrain relief.

Figure 2.

Location of the Kampinos commune relative to neighboring communes and the borders of the Kampinos National Park. Source: Own study based on the Database of Topographic Objects and the State Register of Borders, Topographic Database and Polish Geological Institute—National Research Institute.

The area of the commune is located in the Bzura watershed (a left tributary of the Vistula). Waters from its northern part flow through the Olszowiecki Canal and Łasica Canal to Łasica (a tributary of Bzura), while the southern part is within the Utrata watershed (a right tributary of Bzura). In the north of the commune, within the floodplain and over-flood terraces of the Vistula, there are wetlands, peat bogs, and marshy areas. The lowest point of the commune is the bottom of the Łasica Canal in the area of Karolinowo—68.4 m a.s.l. The highest point is located north of the village of Zawady—95.1 m a.s.l. In the Kampinos commune, 1700 hectares of land are reclaimed—covered by a 50 km network of drainage ditches. This is only about half of the land that requires reclamation. Moreover, on a large part of these lands, the condition of the reclamation facilities is inadequate, due to the age of the facilities (1960s/1970s) and the low quality of materials used to construct the drains.

2.2. Inhulets Irrigation Network—Characteristics of Selected Study Area in Ukraine

In the case of the area in Ukraine, the implementation of the adopted study objective was carried out using the example of the Inhulets Irrigation Network, which includes 55 farms in the Mykolaiv and Kherson regions, covering over 62.7 thousand hectares (43.7 thousand hectares in Mykolaiv region and 19 thousand hectares in Kherson region). The irrigation covers the lands of the Bashkansky and Mykolaivsky districts of the Mykolaiv region, as well as the Berislavsky and Khersonsky districts of the Kherson region (Figure 3).

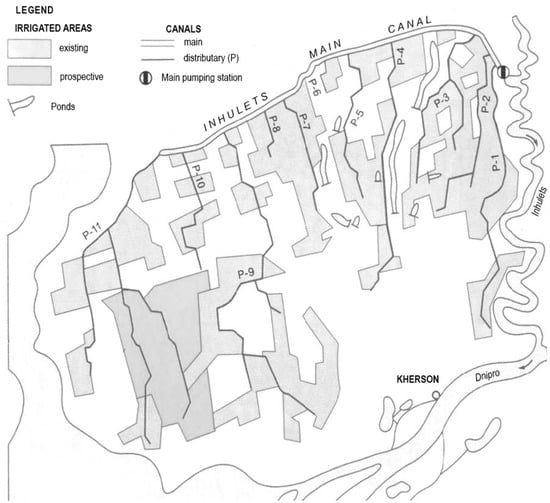

Figure 3.

Location of the study area in Ukraine. Source: Own study based on the State Land Cadastre and Topographic Database.

The first phase of the Inhulets irrigation system was put into operation in November 1956, providing irrigation for 10,800 hectares of irrigated lands. The construction of the Inhulets irrigation system lasted until 1963. The Main Pumping Station and the main canal were built during this period. Initially, the main canal was designed and constructed as an earthen channel. The project did not include concrete or reinforced concrete lining for the canal due to the high cost of the works. This led to significant water losses through filtration, raised groundwater levels, and flooding of adjacent areas. Therefore, in 1967, a reconstruction project began. Partial lining of the main canal was carried out using monolithic concrete and reinforced concrete slabs (Figure 4). This reduced water losses and allowed for the addition of further irrigated areas, namely the Spaska irrigation system [62].

Figure 4.

Main canal of the Inhulets irrigation system. Source: [63].

According to the development program of land reclamation in southern Ukraine, the expansion of irrigated areas was carried out. In connection with the construction of the Yavkynska irrigation system in 1985, the Yavkynska Pumping Station (PS) was put into operation alongside the Inhuletska Main Pumping Station (MPS), with water being supplied to the Inhuletskiy Main Canal. At the same time, the capacity of the main canal was increased to 62.4 m3/s. The total length of the main and distribution canals is 343 km, with a total of 621 hydraulic structures. The source of irrigation is the Dnieper River, from where water is diverted and directed into the Inhulets River, which, in turn, is cleared and deepened up to the main pumping station. Irrigation canals are constructed on embankments or semi-embankments due to the flat terrain of the irrigated areas. Along the northern boundary of the irrigated area, a main canal with a length of 53.3 km runs from east to west. From this main canal, 11 interfarm distributaries extend from north to south, covering a total length of 361.5 km, while the internal farm canals have a combined length of 1263 km (Figure 5) [62].

Figure 5.

Scheme of the Inhulets irrigation system. Source: [64].

The advantage of the Inhulets irrigation system lies in the fact that the flow of water in the direction of all distributaries (branching off to the south) coincides with the natural slope of the terrain. The main destabilizing factors of the irrigation system are the unsatisfactory condition of the existing irrigation and drainage potential utilization, the wear and tear of the engineering infrastructure of the reclamation systems (70%), and the uncertainty of the legal status of the reclamation systems and property rights on them.

2.3. Case Selection Reasoning

Both case studies were selected to best reflect the agricultural, economic and climatic conditions prevailing in both countries. The intended goal was to obtain the most universal conditions possible in terms of lowlands of Poland and Ukraine so that the study findings could be transposed to the rural areas of lowlands in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

When it comes to Poland, the selected case study is located in the Mazowieckie Voivodeship, which is recognized as the most internally diverse region in Europe after London according to OECD. In the center of the region, a positive phenomenon of diffusion of development from the metropolis to the external surroundings is observed, whereas its primarily agricultural peripheries comprise one of the poorest communes in Poland. It takes first place in terms of both the size of rural areas and population in the structure of Polish voivodeships. Due to its high spatial variability, it demands higher flexibility of the agricultural sector. They are also characterized by some of the greatest water shortages in the growing season in the country, and therefore, there is a risk of agricultural drought. The Kampinos case study is characterized by a high demand for the construction of new irrigation and drainage facilities as well as the modernization and improvement of the technical condition of existing facilities. The priority action in the research area is to slow down the outflow of rainwater and meltwater, store water in periods of excess, and use it in periods of drought.

Regarding Ukrainian research area, the Inhulets irrigation system is located in the arid Southern region, within the boundaries of Mykolaiv and Kherson oblasts. The irrigated land area covers 62.7 thousand hectares, while the total area of water supply reaches 175 thousand hectares. The soil cover is represented by southern humus-rich chernozems and dark chestnut soils. At a depth of several meters below the surface lie horizons of easily soluble salts, which negatively affect the condition of irrigated lands. In particular, issues such as waterlogging, irrigation-induced soil erosion, and other adverse processes are observed. The establishment of WUA on the largest open-type irrigation system in Ukraine should become an important step toward the effective management of land and water resources in the region.

Selected areas in both countries share similar climatic conditions and agricultural dependencies, including uneven rainfall distribution, periods of both excessive and insufficient soil moisture, significant water deficits during the growing season, and the threat of agricultural drought. These challenges necessitate the implementation of land reclamation measures on agricultural lands and actions aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change in rural water resources management. WUAs can play a key role in this process by uniting the efforts of local landowners and farmers to enhance the natural water retention capacity of catchments and improve water supply efficiency within watersheds through sustainable land and water management practices.

3. Results

We divided obtained study results into three main sections. Firstly, we present results of analyses on water management in agricultural areas in Poland and Ukraine, taking into consideration both historical conditions and current challenges of water management in rural areas of both countries. Secondly, we report findings on legal, organizational, and financial peculiarities of WUAs functioning in Poland and Ukraine. Lastly, we provide results of the investigation on practical problems of WUA functioning based on selected case studies in Poland and Ukraine.

3.1. Water Management in Agricultural Areas in Poland and Ukraine: Historical Conditions and Current State

3.1.1. Historical Conditions for the Development of Irrigation and Drainage Systems and Water Law Companies in Poland

The beginnings of reclamation activities and the regulation of riverbeds in Poland date back to the 12th century, with the aim of enabling settlement on fertile floodplain areas [65]. Meanwhile, the earliest accounts of the formation of water law companies date back to the 14th century; they based their operations on customs, which by the early 15th century saw legal regulations [66].

The most intense development of both agricultural reclamation and water law companies in Polish territories occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries [67]. The most crucial area of activity for water law companies at that time was protecting lands from floods, particularly through the construction and maintenance of flood barriers and drainage systems [68].

The term “water law company” was introduced into the Polish legal order by the Water Law Act of 19 September 1922, which detailed their organization and functioning, enabling existing companies based on Prussian or Austrian law to continue operating, and introducing this legal institution to the territories of the former Russian partition [66]. This act remained in force until 1962 and granted state administration authorities the competence to (i) create so-called “compulsory water law companies” in the interest of the public good, (ii) forcibly include a specific entity in an existing or newly established company, and (iii) impose on entities not belonging to the company the obligation to pay contributions for the properties they owned. Authorities supported the development of water law companies, among other things, by ensuring them easy access to credit and other forms of public assistance. At the same time, actual control over the quality of the designed reclamation investments or the level of their execution was not exercised. This led to a decline in the level of water and land reclamation works, and in the longer term was the cause of the financial collapse of many water law companies, whose technical infrastructure did not meet the expectations placed in them and often did not function at all [66].

After World War II, an initiative was launched to reactivate water law companies, supported by guidance from the Ministry of Agriculture and Agricultural Reforms [68]. This was also a period of revitalization of reclamation works in Poland, which continued until the 1990s [67]. The goal of introducing a reclamation system in Poland was to rapidly increase the area under agricultural production. After 1945, these works began on a large scale—priority was given to ensuring safety and growth based on efficient agriculture. Initially, the system of drainage ditches equipped with sluices and gates, planned for areas subject to periodic flooding, was not intended to drain these areas but only to regulate the water level. In practice, however, these systems are rarely efficient today, and the current maintenance work, which involves only clearing and cutting back vegetation, results in accelerating water runoff.

The years 1950–1955 brought a crisis in the operation of water law companies, which lost the support of the authorities aiming to create a strong system of territorial water management administration bodies and considering the existence of other, especially independent organizations within the state water management system unnecessary [66]. After 1956, the state authorities changed their attitude towards water law companies, gradually offering them increasing support and assigning them tasks previously performed by water management administration bodies, including the development of water reclamation and the expansion of water supply and sewage systems. With the enactment of the new Water Law in 1962, the state authorities recognized the useful and positive role played by water law companies and sought to popularize this institution (including through various forms of assistance), while reserving extensive influence over the activities of water law companies through supervisory powers [66]. The autonomy of water law companies and the possible scope of activities for individuals who were members of these companies were limited, turning these institutions into instruments of state-controlled planned water management. The peak development of water reclamation occurred between 1965 and 1975. Since 1991, there has been a progressive regression in reclamation—due to the poor profitability of agricultural production and protests by environmentalists [69]. Therefore, water reclamation facilities in Poland were mainly built in the 1960s–1980s on agricultural lands with varied ownership structures, mostly belonging to private entities—farmers—and were largely financed by state funds.

With the change in the political system in Poland in 1989, the state ceased exerting pressure to create and maintain water law companies, reduced the scope of supervisory powers of state administration bodies over these companies, and decreased the assistance provided to them [66]. The new Water Law enacted in 2001 adjusted Polish law to the legal standards of the European Union and introduced a comprehensive reform of water law companies. The interference of public administration in the operation of water law companies was limited, and flexible legal frameworks for the operation of these companies were created. The legislator moved away from the concept of compulsory creation of water law companies by public authorities against the will of the entities included, and also limited the possibilities of forcibly incorporating property owners or users into water law companies. The scope of supervisory competencies exercised by administrative bodies was reduced. Forms of administrative assistance were limited to grants only, while previously applicable regulations also indicated other forms of assistance, such as material, training, and organizational support [66]. The currently valid Water Law, adopted in 2017, has upheld these changes.

3.1.2. Historical Conditions for the Development of Irrigation and Drainage Systems and WUAs in Ukraine

Important stages in the development of land reclamation in Ukraine included the construction of the Dniprohydrouelectric Power Station (1932); the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Power Station with a reservoir, which enabled irrigation in the southern part of Ukraine (since 1951); the Inhulets, Krasnoznamyanska, and other large interfarm irrigation systems (1960s); and more modern systems utilizing progressive machinery and equipment (since the 1960s). The largest systems in Ukraine include the North Crimean Canal (1970s–1980s), which provides irrigation and water supply to the Crimean Peninsula, and the Trubizh, Irpin, Soloki, and other drainage systems [70].

During the construction of irrigation systems in the Soviet Union, they were designed in large clusters with an average area of 1200–1500 hectares. These irrigation systems allowed for crop rotation and efficient use of wide-span agricultural machinery. The irrigation systems built in Ukraine during the 1960s to 1980s were on par with the best global examples and, in some technical aspects, even surpassed them. Irrigation on over 96% of the area was carried out using the rainwater method, employing high-productivity wide-span machines such as the Frigate, Dnipro, and Kuban [71].

In the early 1990s, Ukraine had a significant area of irrigated land—2.6 million hectares (approximately 7% of the arable land). These lands accounted for almost 15% of crop production. However, widespread irrigation exacerbated the ecological situation in several regions without fully solving the food problem. In 1993, the Ukrainian government issued a resolution on land reclamation, demanding its scientific, ecological, and economic justification.

Unfortunately, with the onset of the prolonged economic crisis in the 1990s in Ukraine, irrigated lands gradually lost their potential. Due to a sharp reduction in budgetary funding, the construction of new irrigation systems and the reconstruction of existing ones were completely halted.

As of the year 2000, the area of irrigated land in Ukraine had decreased to 2.45 million hectares, with the majority concentrated in the steppe zone—2.1 million hectares, or 85%. In the forest-steppe zone, 356 thousand hectares were irrigated, and in the Polissia region, this was 11 thousand hectares. The share of irrigated fields constituted 8.4% and 12.8% of the total area of agricultural lands and arable lands in the country, respectively. In the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, the ratio of irrigated land to arable land was 29.2%, while it was 25.6% in the Kherson region, 13.4% in Zaporizhia, 11.4% in Dnipropetrovsk, 11.2% in Odesa, 11.1% in Mykolaiv, and 9.4% in Donetsk [72].

In 2006, the Decree of the President of Ukraine “On Measures for the Development of Irrigated Agriculture in Ukraine” was issued. Among other things, it obligated the government to implement measures to improve the ecological condition of irrigated and drained lands by the year 2010 through the following:

- Conducting reconstruction and construction of irrigation systems, prioritizing the development of irrigated agriculture and rice cultivation in the southern regions of Ukraine;

- Technically upgrading irrigation systems and adopting advanced irrigation technologies, manufacturing modern machinery and equipment for irrigation and other modern irrigation techniques;

- Providing state support for agricultural production on irrigated lands;

- Offering compensatory payments to agricultural producers related to the construction and reconstruction of irrigation systems.

At the regional level, local government administrations were required to support, following this:

- The transfer of objects of engineering infrastructure of internal melioration systems into communal ownership according to established procedures;

- Ensuring optimal operating regimes for reservoirs and water management systems;

- Preventing the destruction of engineering infrastructure of melioration systems, dismantling, and looting of irrigation systems, especially metal pipelines and sprinkler equipment;

- Developing regional programs to support the development of irrigated agriculture;

- Establishing cooperatives for the maintenance of internal melioration systems by their owners, as well as public organizations and associations of water consumers [73].

However, the majority of the funds were directed towards the maintenance of institutions, enterprises, and organizations of the State Committee of Ukraine on Water Management. The activities related to the construction of irrigation systems, the acquisition of new irrigation machinery, and the modernization of reclamation facilities were not carried out.

In 2015, the government approved the Single and Comprehensive Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development in Ukraine 2015–2020, which provides a strategic framework for the development of the agricultural sector as a whole, addressing crop production, land tenure and land management, access to credit, taxation, agricultural research and education, state support mechanisms, food safety, environment, and other related issues. However, the strategy did not sufficiently address the role of irrigation and drainage in Ukraine.

A positive development was the adoption of the Irrigation and Drainage Strategy in Ukraine in 2019. The implementation of the Strategy is planned for the period up to 2030 and will be carried out in three phases through the execution of an action plan aimed at restoring and developing irrigation and drainage systems in Ukraine.

3.1.3. Current Challenges of Water Management in Rural Areas in Poland

Poland is considered a country poor in water resources, and the uneven distribution of precipitation throughout the year and over multiple years causes periods of excess and deficiency of water [74,75]. Areas with insufficient water resources cover about 60% of Poland’s surface [76]. The threats include a decrease in the groundwater level, disappearance of ponds, and the periodic disappearance of smaller watercourses [77]. The capacity of all retention reservoirs in Poland is about 4.1 billion cubic meters, which constitutes only 6.5% of the volume of the average annual river runoff, while the physiogeographic conditions would allow for the storage of 15% of the average annual runoff [78,79].

Among the adverse factors are the frequent occurrence of extreme hydrological phenomena such as droughts and floods. In Poland, all types of drought occur, including atmospheric, agricultural, hydrological, and hydrogeological droughts, the latter characterized by a drop in groundwater levels. There is an increasing frequency of torrential rainfall and so-called flash floods, which do not allow for sufficient and long-term soil hydration. In the country, rainfall and meltwater floods are most common, but over the last 40 years, nearly all possible types of floods have occurred in the Republic of Poland [80]. The most dangerous floods caused by atmospheric precipitation mainly occur in the southern, southeastern, and southwestern regions of Poland, while floods caused by melting snow and downpours are characteristic for the central part of Poland [80,81,82]. Approximately 2 million hectares of agricultural land are at risk of flooding, half of which are protected by embankments [83].

Another significant issue in water management in the country is the inadequate quality of waters. According to monitoring data from 2014–2019 [84], the general condition of the uniform parts of surface waters was classified as poor for 91.5% of the assessed uniform parts of river surface waters and reservoirs and for 88.1% of the assessed uniform parts of lake surface waters.

The significant temporal and spatial variability of atmospheric precipitation and flow rates in watercourses, along with the limited size of water resources in Poland, necessitates rational water management [85,86]. The occurrence of flooding in the same areas, followed by periods of harmful water shortage, causes considerable damage to Polish agriculture [87].

Both the quantitative state and the maintenance of water reclamation facilities in Poland should be considered unsatisfactory. According to data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, it is estimated that as much as 9.2 million hectares of agricultural land in Poland require reclamation, which should serve both irrigation and drainage functions, i.e., watering areas during droughts and storing water during heavy rainfall for rainless periods [88]. The area of reclaimed agricultural land in Poland is 6.4 million hectares, with water law companies covering 4.1 million hectares of reclaimed land [60]. A concerning issue is the lack of proper maintenance and interest in the exploitation of existing reclamation facilities, which leads to the need for their reconstruction or modernization [89]. In Poland, the area of lands maintained by water reclamation facilities amounts to 3.0 million hectares, which is only 46.6% of the area of all reclaimed lands [60]. Meanwhile, facilities on a total area of 1.4 million hectares of agricultural land require reconstruction or modernization [60].

3.1.4. Current Challenges of Water Management in Rural Areas in Ukraine

The current state of reclaimed lands in Ukraine is characterized by a significant deterioration in the resource provision of agriculture on reclaimed lands, especially irrigated ones, leading to a considerable decline in production volumes. Negative processes of secondary waterlogging are developing on drained areas. Almost 30% of drained lands are used as unproductive meadows and pastures. The intervals between flood and inundation events are increasing due to the siltation of canals and drainage collectors and their overgrowth with shrubs. The irrigation systems are failing, and control valves and pipelines are being dismantled. Additionally, the aging of vertical and horizontal drainage systems or their absence has resulted in periodic flooding of 210 rural settlements and 90,000 hectares of agricultural land.

As a result of the reform of the domestic agricultural sector, the intrafarm meliorative system was damaged, destroyed, and looted. Consequently, the meliorative system lost the integrity of its engineering infrastructure, as state pumping stations and canals involved in the water supply process far exceed the capabilities of agricultural producers to receive and distribute it in the fields. In Ukraine, only 25–30% of the total area of irrigated lands is currently being irrigated due to these challenges [90].

Additionally, the ownership rights to the engineering infrastructure of the reclamation systems and its individual components were divided among the state, territorial communities of villages, towns, and cities, legal entities, and citizens of Ukraine (Table 1).

Table 1.

Types of ownership forms for land reclamation systems in Ukraine. Source: Own elaboration.

In essence, a paradoxical situation arose where the interfarm network remained under state ownership and management, while the intrafarm network, which was part of the dissolved collective and state farms, ended up practically ownerless. This led to its looting and destruction. Small landholders were unable to organize the maintenance of irrigation machinery and watering systems, carry out repair works, let alone allocate financial and technical resources for reconstruction and modernization [91].

With the aim of ceasing the complete destruction of the internal economic network, the government of Ukraine has adopted a decision on the free transfer of the internal agricultural drainage network to the municipal ownership of rural councils [92]. However, this only applied to the network of objects of engineering infrastructure that were not subject to consolidation during the reform of collective agricultural enterprises. The legal status of those that were subject to consolidation was undefined, meaning they remained ownerless.

Due to the uncertainty of the legal status, rights and responsibilities, control over their usage, as well as the presence of a significant number of ownerless objects, practical measures for the maintenance and ensuring the functionality of the internal farm engineering infrastructure were not implemented.

There were also cases where economic entities independently conducted communications for irrigation and established their own water intake without obtaining any permits. Their activities and the volumes of water resource utilization were not monitored by anyone. This led to a negative impact on the environment, uncontrolled resource usage, and failure to obtain funds for the state.

Currently, the country’s irrigation infrastructure operates at only a quarter of its potential capacity due to prolonged lack of investment and an outdated water supply system. Considering the importance of proper irrigation and drainage for agricultural production, the need to invest in restoring these systems is evident. Furthermore, the recently launched land market provides landowners with more opportunities to invest in costly technologies such as irrigation.

3.2. Legal, Organizational, and Financial Peculiarities of WUA Functioning in Poland and Ukraine

3.2.1. Legal Basis for the Functioning of WUAs in Poland

“Water law companies” are the only form of WUAs permitted under Polish law. The Polish Water Law Act adopted in 2017 defines “water law companies” as non-public organizational forms, which operate not for profit, bring together individuals or legal entities on a voluntary basis, and aim to satisfy the needs specified by the law in terms of water management [93] (Art. 441). The activities of water law companies particularly include: (i) the construction, maintenance, and operation of facilities for providing water to the population, facilities for protecting waters from pollution, and water reclamation facilities, (ii) protection against floods, and (iii) drainage of built-up or urbanized lands [93] (Art. 441).

According to the provisions of the Act of 20 July 2017 on Water Law [93] (Art. 199), the construction of water reclamation facilities is the responsibility of landowners; however, it may be financed by the State Treasury, as well as with the involvement of community funds and other public funds (with a partial reimbursement of costs by the landowners). The operation, maintenance, and performance of repairs on water reclamation facilities to preserve their function belong either to the interested landowners or to a “water law company” (or an “association of water law companies”) if these facilities are covered by such activity [93] (Art. 205).

The creation of a WLC occurs through an agreement of at least three individuals or legal entities, made in written form, and requires the adoption of the statutes of the WLC and the election of its bodies [93] (Art. 446). A WLC acquires legal personality upon the finalization of the county governor’s (starosta) decision to approve the statutes of the company. Supervision and control over the activities of a WLC are exercised by the appropriate local county governor, while for associations of water law companies, this duty is performed by the voivode (provincial governor) [93] (Arts. 444 and 462).

3.2.2. Legal Basis for the Functioning of WUAs in Ukraine

The Law of Ukraine No. 2079-IX, dated 17 February 2022, “On Water User Organizations and the Promotion of Land Hydrotechnical Amelioration,” introduced for the first time in Ukraine a new organizational and legal form for managing reclamation systems—the Organization of Water Users (WUO).

A WUO is a non-profit legal entity established by owners and/or users of agricultural land plots to ensure the use, operation, and maintenance of engineering infrastructure facilities of reclamation systems, with the aim of providing hydrotechnical land reclamation services within the service area of the organization’s reclamation network [94].

Specifically, the law regulates that this organization is created to effectively carry out hydro-technical reclamation on agricultural land plots within the territory served by the organization. A WUO is not allowed to engage in the production of goods, provide services, or carry out work not related to hydro-technical reclamation, except in cases of producing and selling by-products during the main activities of the organization. The revenue from the sale of such by-products is exclusively used to finance the statutory activities of the organization [95].

In accordance with the provisions of the Law of Ukraine “On the Organization of Water Users and Promotion of Land Reclamation,” a model charter for a WUO has been developed. This charter defines the legal status, rights, obligations, and relationships of the members of a WUO, the procedure for creating such an organization, the governing bodies of a WUO, their powers, the main directions of the organization’s activities, the procedure for conducting economic activities, and the termination of the WUO [94].

The Model Charter defines that a WUO is formed by the owners of agricultural land plots that have not been transferred for use, and/or users of agricultural land plots on the right of lease, sublease, emphyteusis, and permanent use, who have a permit for special water use if the need for such a permit by the water user is provided by law. The main purpose of this organization is to effectively carry out hydro-technical reclamation on agricultural land plots that are included in the organization’s service area and where water use is conducted for the needs of hydro-technical reclamation or where there is a technical possibility for its implementation [95].

3.2.3. Organizational Peculiarities of WUA Functioning in Poland

The organs of the water company are (i) the general assembly, (ii) the board, and (iii) the audit committee. The responsibilities of the general assembly of the company members include adopting the work plan, schedule of individual activities, their order along with the deadlines for the execution of works, and the budget allocated for these activities for the given year. This plan, like any other formal document, is adopted by resolution, which is subject to the supervision of the starost (county governor). The starost checks the compliance of the resolution with the law and the company’s statutes, which are the legal basis for the company’s operations. The formation of the company, the agreement regarding the company, and the statutes approved by the starost’s decision transfer the owner’s responsibilities for the maintenance of water drainage facilities to the water company. The company acts as a kind of proxy for the owners, becoming a legal entity on the day the statutes are approved by the starost through a decision.

The landowner who benefits from the water drainage facilities is a member of the general assembly. As a member of the company, they can exercise their rights at the general assembly and submit proposals to include work on their land in the annual task plan. However, if an individual owner fails to pay the dues, they can be removed from the company’s membership.

The State Water Management Authority, ‘Wody Polskie’, can conduct an Inspection either ex officio or upon request (e.g., from a member of the water company whose request for the maintenance of a specific water drainage facility was ignored at the general assembly). This inspection focuses on water management, including the maintenance of waters and water facilities, to ensure that the water drainage facilities are properly maintained by the water company, comply with the law, and are not at risk of depreciation. By conducting a water management inspection, it can be determined whether the company is fulfilling its statutory duties. In the case of improper actions by the company, appropriate legal measures can be taken against it.

The starost (county governor) can declare the resolutions of the general assembly invalid and suspend their execution. If the board repeatedly violates legal regulations or the provisions of the statutes, the starost can also dissolve the board and appoint a person to perform the board’s duties. Additionally, the starost can dissolve the water company if: (i) its activities violate legal regulations or the provisions of the statutes, (ii) the term for which the commissary board was appointed has expired, and the general assembly has not elected a new board, and (iii) the number of members is less than three.

3.2.4. Organizational Peculiarities of WUA Functioning in Ukraine

A WUO is established and operates on the following principles:

- Voluntary membership in the WUO;

- Open membership for owners who independently use the land plots included in the organization’s service area and users who have been granted the right to use land plots within the organization’s service area;

- Self-governance;

- Transparency and accessibility of information about the organization’s activities;

- Ensuring the protection of rights and legitimate interests of landowners and land users;

- Ensuring compliance with environmental safety requirements in the use of land and water resources [94].

The formation of a WUO is preceded by a preparatory stage, the main goal of which is to ensure the organization and conduct of the constituent assembly. The relevant procedure must be initiated by a person interested in establishing the WUO. Only a person who can act as the founder of the WUO can be such an individual.

The founders of a WUO can be water users who have a valid permit for special water use if obtaining such a permit is mandatory according to the law and they meet the following criteria [94] (Law No. 2079):

- Owners of agricultural land plots that have not been transferred to use and on which water use is carried out for the needs of hydrotechnical reclamation, or there is a technical possibility for water use for the needs of hydrotechnical reclamation;

- Users of agricultural land plots on the basis of lease, sublease, emphyteusis, and permanent use rights, where water use is carried out for the needs of hydrotechnical reclamation, or there is a technical possibility for water use for the needs of hydrotechnical reclamation.

It is important to note that the owner of an agricultural land plot transferred for use under lease or emphyteusis conditions cannot become a founder and acquire membership in the organization. Therefore, the founders of a WUO can be water users who directly cultivate agricultural land plots.

For determining the service territory of the reclamation network and the composition of land plot owners (users) included in it, assigning a cadastral number to the land plot is essential. If the cadastral number is absent in the state act, an extract from the State Land Cadastre or the State Register of Property Rights for the respective plot should be additionally provided.

For the purposes of creating a WUO, all land plots located within the irrigation system are considered, regardless of whether they have objects of engineering infrastructure of reclamation systems and regardless of whether they are actually irrigated.

It should be noted that for water users, the following circumstances serve as incentives to become members of a WUO:

- Influence through participation in general meetings to make key decisions regarding the activities of WUO. This includes the approval of service provision rules, tariffs for services or their formation methodologies, the development of WUO’s strategy, and its investment plans. It also includes the ability to influence the formation of the executive and supervisory bodies managing WUO, among other things.

- Preferential access to water in situations where the water resource is limited due to insufficient water volume in the irrigation source or due to emergencies [94].

Based on the results of reviewing the submitted documents, the registration commission determines the presence of land users, landowners, and water user status for each participant, and determines the additional votes of the participants. During the voting at the founding meeting, each land plot owner (user) has one primary vote regardless of the number of land plots they own (use), and additional votes are calculated proportionally to the area of the land plot(s) owned (used) by the owner (user) compared to the total area of the organization’s serviced territory. If a part of the land plot is included in the organization’s serviced territory, additional votes are calculated proportionally to the area of that part compared to the total area of the organization’s serviced territory.

A decision on the creation and determination of the territory served by WUO is adopted if it receives:

- Over 50% of the primary votes of land plot users (owners) who participated in the founding meeting;

- Over 50% of the additional votes of land plot users (owners) who participated in the founding meeting.

3.2.5. Financial Peculiarities of WUA Functioning in Poland

Water companies can engage in activities that enable them to generate profit, which is allocated exclusively for the statutory purposes of the water company, and they must maintain appropriate accounting books and financial reports [93] (Art. 441). The water company is liable for its obligations with all its assets; however, a member of the water company is not liable for the company’s obligations [93] (Art. 451). A member of the water company is obliged to pay membership fees and other contributions specified in the statutes, appropriate to the company’s goals [93] (Art. 452). The amount of membership fees and other contributions to the water company is determined by the company’s statutes and should be proportional to the benefits received by the members in connection with the company’s activities [93] (Arts. 448 and 453). If individuals or legal entities who are not members of the water company, as well as organizational units without legal personality, benefit from the company’s facilities or contribute to the pollution of the water that the water company is established to protect, they are also obliged to bear monetary or non-monetary contributions to the company [93] (Art. 454).

Water companies can also benefit from state financial assistance provided in the form of subject-specific grants from the state budget aimed at subsidizing ongoing activities related to the maintenance of waters and water facilities [93] (Art. 443). There is also the possibility of obtaining financial assistance in the form of targeted grants from the budgets of local government units for the ongoing maintenance of waters and water facilities, as well as for financing or cofinancing investments based on an agreement concluded between the local government unit and the water company [93] (Art. 443).

3.2.6. Financial Peculiarities of WUA Functioning in Ukraine

With the aim of providing state support to WUOs and promoting hydro-technical land reclamation in Ukraine, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine approved the “Procedure for the use of funds provided in the state budget to provide state support to agricultural producers using reclaimed land and WUOs.” This procedure establishes the mechanism for granting subsidies to agricultural producers to restore the operation of pumping stations used for land irrigation.

This order defines the mechanism for using funds allocated in the state budget by the Ministry of Agrarian Policy under the program “Financial Support for Agricultural Producers” aimed at providing state support to agricultural producers using irrigated lands and WUOs. According to the budgetary program, these funds are directed to provide state support to agricultural producers who use irrigated lands and engage in agricultural activities with the application of hydro technical reclamation. This support aims to enhance agricultural efficiency in the context of climate change, stimulate an increase in the area of irrigated lands, and boost agricultural production. Additionally, the funds are allocated to WUOs for the restoration of non-functioning pumping stations or pumping stations with productivity indicators below the level set by the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine [96].

The government has also established performance indicators for a pumping station that can be transferred to the ownership of WUO. Specifically, it was stipulated that WUO has the right to receive a budget subsidy for the pumping station transferred to its ownership if the combined performance indicators fall below 70% of the designed productivity specified in the pumping station’s passport and the energy efficiency is lower than its calculated level, which is equal to or lower than 54% [97]. Such modernization and reconstruction of pumping stations in the reclamation systems should ensure uninterrupted supply or discharge of water for the needs of WUOs and, in general, contribute to the development of hydraulic reclamation.

A budget subsidy is provided to WUOs for the restoration, reconstruction, modernization, and capital repair of pumping stations commissioned after the relevant works during the period from November 1 of the previous year to October 31 of the current year. The budget subsidy is granted on a non-repayable basis to WUOs, covering up to 50% of the costs (excluding value-added tax) incurred in accordance with the project documentation approved in the prescribed manner.

Another important source of funding for WUOs is obtaining cofinancing within the USAID Agricultural and Rural Development Program “AGRO” for the modernization of irrigation systems. The service area of one project should be at least 200 hectares, and WUO’s participation in subgrant financing should be at least 30% of the total project budget. Cofinancing is provided for work on existing (accounted) irrigated lands or lands that have been irrigated in previous years. At the time of the proposal, intrafarm or interfarm irrigation systems that exist or existed on these lands should be on the balance of communal or water management organizations.

3.3. Practical Problems of WUA Functioning Based on Selected Case Studies in Poland and Ukraine

3.3.1. Study Results for the Kampinos Case Study in Poland

In the Masovian Voivodeship, which includes the Kampinos municipality, among the three types of drainage facilities (drainage, irrigation, and drainage and irrigation), primarily drainage facilities were constructed in practice during the 1970s. Currently, droughts and water shortages are becoming an increasing problem. To address this issue, it is not sufficient to merely deepen the ditches during maintenance; they should also be widened, and retention reservoirs should be built. This is not possible within the existing boundaries of the watercourses.

There is an issue with the lack of visibility of drainage facilities on maps. To receive a grant for the maintenance of these facilities, it is required to attach maps showing the layout of the drains to the application. The existing maps only show the layout of the planned facilities, and in practice, the actual state deviates from the project by several, or even several dozen, meters. Wody Polskie also does not have information on the location of the drainage facilities. Therefore, an inventory of the drainage facilities is essential.

A system of drains and ditches that is not connected to a system of sluices and retention reservoirs with monk structures serves only to drain water from fields into ditches, from which the water flows into rivers. The drainage outlets are located about 30 cm above the bottom of the ditches. If a system of sluices and monk structures were applied on a larger scale, it would be possible to retain water and use the same drains that carry water from the fields to the ditches to irrigate the fields during periods of water shortage in agricultural areas.

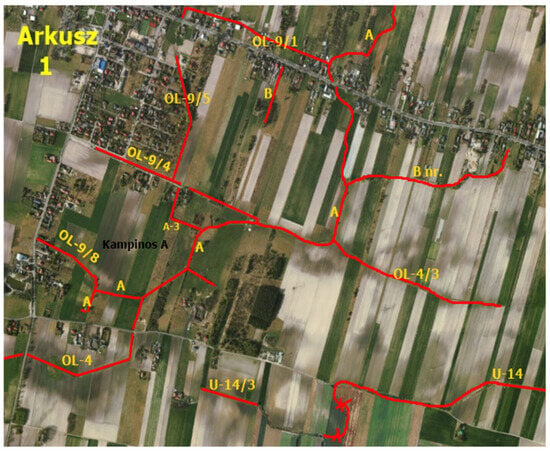

In the Kampinos municipality, 1700 hectares of land are drained, covered by a 50 km network of drainage ditches. This accounts for only about half of the land that requires drainage. Additionally, a large portion of this land has drainage facilities in poor condition due to the age of the facilities (from the 1960s/1970s) and the low quality of materials used in the construction of the drains. The drained areas are depicted on approximately 70 maps. Figure 6 shows a fragment of an orthophotomap with the layout of the drainage pipelines marked by an employee of the municipal water company.

Figure 6.

Orthophotomap with the layout of drainage pipelines marked. Source: [61].

The entire drainage system in the Kampinos municipality relies solely on drainage. There are no existing water-retaining sluices due to a lack of funds. Constructing these sluices does not seem like a costly investment, especially considering the significant benefits of retaining water and supplying it to agricultural fields during drought periods. The Kampinos municipality needs to build approximately 30 sluices. The cost of one sluice is about 5000 PLN (approximately 1100 EUR). In total, with an amount of 150,000 PLN (approximately 33,300 EUR), the water management conditions for agricultural production could be significantly improved throughout the municipality. The issue with grants, including those from the Marshal of the Voivodeship, is that they are designated exclusively for the maintenance of existing drainage facilities. Thus, these funds can be used for mowing and dredging ditches, but they cannot be utilized for constructing irrigation facilities, especially sluices.

The effects of the maintenance work carried out by the municipal water company “Kampinos” in the villages of Wiejca, Kampinos A, Wola Pasikońska, and Komorów are shown in the photographs—Figure 7 and Figure 8. The photograph in Figure 7 depicts a drainage ditch before maintenance—mowing and deepening. The photograph in Figure 8 shows a drainage ditch after maintenance work.

Figure 7.

Drainage ditch before maintenance. Source: [61].

Figure 8.

Drainage ditch after initial maintenance. Source: [61].

The siltation and weed infestation of the ditches before maintenance are so severe that the drainage outlets are located below the ditch bottoms. Despite this, the ditches contain a lot of water, which does not drain due to clogged drainage facilities. After maintenance, the drainage outlets were found and are now above the bottom of the ditches after deepening them. Unfortunately, the maintenance activities caused the water in the ditches to flow into the rivers and eventually into the sea. If water retention devices, such as sluices, had been installed after the maintenance, the water would have been retained in these ditches and returned to the fields during drought periods through the same drains that carried it away when there was too much water in the fields.

The approved work plan for 2023 includes the following activities:

- Repair of drainage failures.

- Maintenance of drainage ditches: (a) clearing drainage ditches of trees and shrubs, (b) repairing and cleaning drainage outlets and clearing drainage pipes, (c) desilting the ditch bottoms and spreading the silt on the ditch crowns, and (d) mowing drainage ditches.

- Repair of culverts and drainage wells.

- Hiring one person on a contract basis to cut down trees and shrubs from drainage ditches and clean drainage wells.

According to a statement from the General Assembly of Delegates of the Kampinos Water Company, “the company has been carrying out work exclusively using its own financial resources (financial reserve from 2021 and current contributions) practically since January 2022.” The delegates declare: “Unfortunately, our financial capabilities are now severely limited, and there will undoubtedly be a noticeable slowdown in fieldwork. Further large-scale work will be possible only after receiving grants. Not only our company faces such problems. Generally, water companies and their activities depend on weather conditions, the state of crops in the fields, and, of course, financial resources. Not every company can afford to carry out continuous fieldwork throughout the year. In light of the above situation, the Board requests: please do not exert continuous pressure on us to urgently address your reports. No report from you is ignored or put away. We strive to, sooner or later, go to the field, document the situation, and take action. Unfortunately, the technical condition of the drainage facilities in our area is, to put it simply, poor. The company cannot address all reports in one season. Additionally, please understand the situation in which the Board operates. As I have repeatedly emphasized in previous communications, we are not full-time employees of the Company. Our work is solely based on voluntary engagement. Due to the need to save funds, the Company also does not employ any office or field workers. We are not a business like a city office or a municipal green area management company serving residents. We are an association of private individuals who jointly care for the state of drainage on their lands. Unfortunately, the Water Law Act is written in such a way that, for now, we must operate under these conditions.”

3.3.2. Study Results for the Inhulets Irrigation System in Ukraine

The presence of irrigated land in the Inhulets irrigation system amounts to 60.8 thousand hectares, including 18.2 thousand hectares in the Kherson region and 42.6 thousand hectares in the Mykolaiv region. There are 11 interfarm distributors stretching 361.5 km from north to south, along with an internal farm canal network that extends for 1263 km. Additionally, water from the Inhulets Main Canal is supplied to the Yavkinska and Spaska irrigation systems, covering an irrigated area of 50.2 thousand hectares and 10.4 thousand hectares, respectively.

The system consists of two pumping stations with a total capacity of 58,600 kilowatts and a water flow rate of 62.4 cubic meters per second. The total length of the main and distribution channels is 343 km, and it includes 621 units of hydraulic structures.

The technical condition of the irrigation network in the main part of the irrigated lands is relatively satisfactory; most pumping stations are in working order. However, due to insufficient irrigation equipment, its incompleteness, lack of spare parts for the irrigation machines, and a shortage of funds among water users to pay for water, the irrigated lands are not being utilized efficiently. In turn, the internal irrigation network in the majority of farms is in an unsatisfactory technical condition, the pumping stations are disassembled, and the irrigated lands are hardly being used for their intended purpose. The disruption of their technological integrity has been influenced by the division of agricultural lands, leading to decreased efficiency in the utilization of water and land resources within the territory served by the irrigation network. As a result of land privatization, there has been a fragmentation of land plots, and mechanisms for consolidation and responsibility for purpose land use were not regulated (Figure 9). Lands were received as irrigated, but lacking resources, they began to be used for purposes other than intended, such as private estates.

Figure 9.

Land fragmentation of the Inhulets irrigation system. Source: Own study based on the State Land Cadastre.

Based on surveys of land users and landowners, five main reasons and types of land fragmentation in irrigated areas have been identified:

- Large, small, and medium-sized farms—due to owners’ refusal to enter into or termination of lease agreements with land shareholders who wish to use their land themselves or seek higher rental income from the land or intend to sell their land share on the land market.

- Parcels of land within the same rural council belonging to small- and medium-sized farms—as a result of their gradual development and the inability to lease additional land parcels within a unified land mass.

- Deliberate fragmentation by large agricultural holdings and agribusinesses of lands leased in close proximity to irrigation canals by medium and small farms. They propose more attractive rental prices to landowners, consolidating land masses and investing in the restoration of irrigation infrastructure, gradually displacing smaller irrigated areas.

- Lands with damaged on-farm irrigation networks but still accessible to a water source and have the potential for irrigation restoration. In this case, only some land users have the desire and means to invest in their own lands within the unified technological module of the irrigation system, sometimes located beyond its operational zone.

- State-owned lands within rural councils, which are leased out in small plots to individual community members for personal use [98].

Thus, in addition to the fragmentation of land ownership and land use, there was also fragmentation in the lease terms of land parcels within the Inhulets irrigation system, requiring constant renegotiation of lease agreements for specific field areas.

It is worth noting that at the national level, some measures to restore irrigated lands and develop engineering infrastructure have been implemented. Specifically, the minimum lease term for land parcels for commercial agricultural production, farming, and personal peasant farming has been increased to 7 years, and the privatization of objects of engineering infrastructure of meliorative systems and lands where these objects are located has been prohibited. Currently, we have a situation where one part of the irrigation systems belongs to the state, another part is in communal ownership, and a third part is privately owned.

The irrigation system is crucial for the Mykolaiv region. Water is supplied to the Inhulets from the Dnipro River, and then into the main canals. However, the blowing up of the dam of the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station on 6 June 2023 caused a rise in the water level in the Inhulets River, affecting the Inhulets Main Pumping Station. Over three days, the water level in the Inhulets River rose by 6 m. As a result, the Inhulets Main Pumping Station was completely stopped and flooded. Approximately 1000 hectares of agricultural land in three territorial communities of the Bashtansky district were flooded in the Inhulets River area.

Despite the catastrophic consequences of the blowing up the Kakhovka Hydroelectric Station dam, including the uncontrolled flooding of the Inhulets River, water supply for irrigation was restored. Due to the professional work of employees in preserving and restoring equipment at the Inhulets Main Pumping Station, water supply to the Inhulets Main Canal was restored on 13 June 2023, ensuring uninterrupted water supply to the population of Mykolaiv city and agricultural producers in the Kherson and Mykolaiv regions.

An important step in the restoration of irrigation within the Inhulets system was the establishment of the WUO for the Inhulets, Spas, and Yavky irrigation systems on 14 July 2023. Following this meeting, the “INHULETSKA” WUO was formed, which will provide irrigation services to an area of 121,500 hectares, with 103,300 hectares located in the Mykolaiv region and 18,200 hectares in the Kherson region.

The founders of the “Inhulets” WUO are 24 agricultural producers whose lands can be irrigated from the Inhulets River. As of October 2024, the organization is addressing bureaucratic procedures with local government bodies to obtain permits for developing land management documentation for inventory purposes. Since the WUO was established within the service area of 16 territorial communities, it is necessary to obtain approval from each of them. Currently, the WUO has received the necessary permits and has commenced the inventory of reclamation networks within the Bilozerska and Shevchenkivska communities. Only after completing this process can the newly formed association of water users define the reclamation network and enter the relevant data into the State Land Cadastre.

After the state registration of the reclamation network in the State Land Cadastre, the WUO will have the right to receive, free of charge, the ownership of the engineering infrastructure objects of such reclamation network. The engineering infrastructure objects of the reclamation network that are in state or communal ownership or are ownerless and are technologically related to the water intake point of this WUO will be transferred to the WUOs’ ownership free of charge.

The following objects will belong to the engineering infrastructure of the land reclamation network:

- Pumping stations on irrigation and drainage systems, collectors, intakes, and other hydraulic structures;