Encouraging the participation of various kinds of capital in green investment, such as microfinance and insurance, may more strongly promote the development of green finance. At the same time, this innovation pilot zone covers provinces with different economic characteristics, not only provinces such as Zhejiang and Guangdong, where investors are favorable, but also provinces such as Xinjiang and Guizhou, where financing is relatively difficult. Investigating the heterogeneous policy effects among provinces with different geographical locations and economies is crucial for future policymakers to formulate the policy in a more feasible and targeted manner. Concurrently, the development of relatively uniform and clear green finance standards can help green finance policies in different areas be better implemented.

3.1. Theoretical Analysis

Based on the Hartwick law proposed in 1977 and grounded in the research paradigm established by Hartwick [

31,

32], this paper systematically investigates the influence mechanism of green finance on GTQ. Originally introduced in “Intergenerational Equity and Rent for Depletable Resources,” the Hartwick rule was formulated to elucidate how intergenerational equity can be maintained in the context of non-renewable resource utilization. With the growing awareness of environmental sustainability and the increasing demand for a green economy, the Hartwick rule has increasingly been recognized as a pivotal theoretical foundation for green finance practices [

33,

34]. Nevertheless, most existing studies have primarily focused on macroeconomic perspectives and have seldom explored the interaction mechanism between the Hartwick rule and green finance from the standpoint of micro-level enterprises.

As environmental taxation operates through the economic mechanism of taxation, green finance autonomously balances the supply of and demand for environmental goods by assigning scarcity rents to natural resources and internalizing external environmental costs into market accounting [

35]. As illustrated in

Figure 1a, the level of environmental governance can be interpreted as the supply of environmental goods. Scarcity rents serve as compensation for corporate investments, leading to a rightward shift in the supply curve. Consequently, the equilibrium point moves from Q to Q’, thereby increasing the availability of environmental goods. Regarding environmental demand, under conditions of constant consumption levels, this approach reduces total pollution and shifts the overall environmental demand curve to the left without diminishing the value of environmental capital stock. As shown in

Figure 1b, when all scarcity rents are allocated to environmental investment, the pollution level decreases from Q to Q’.

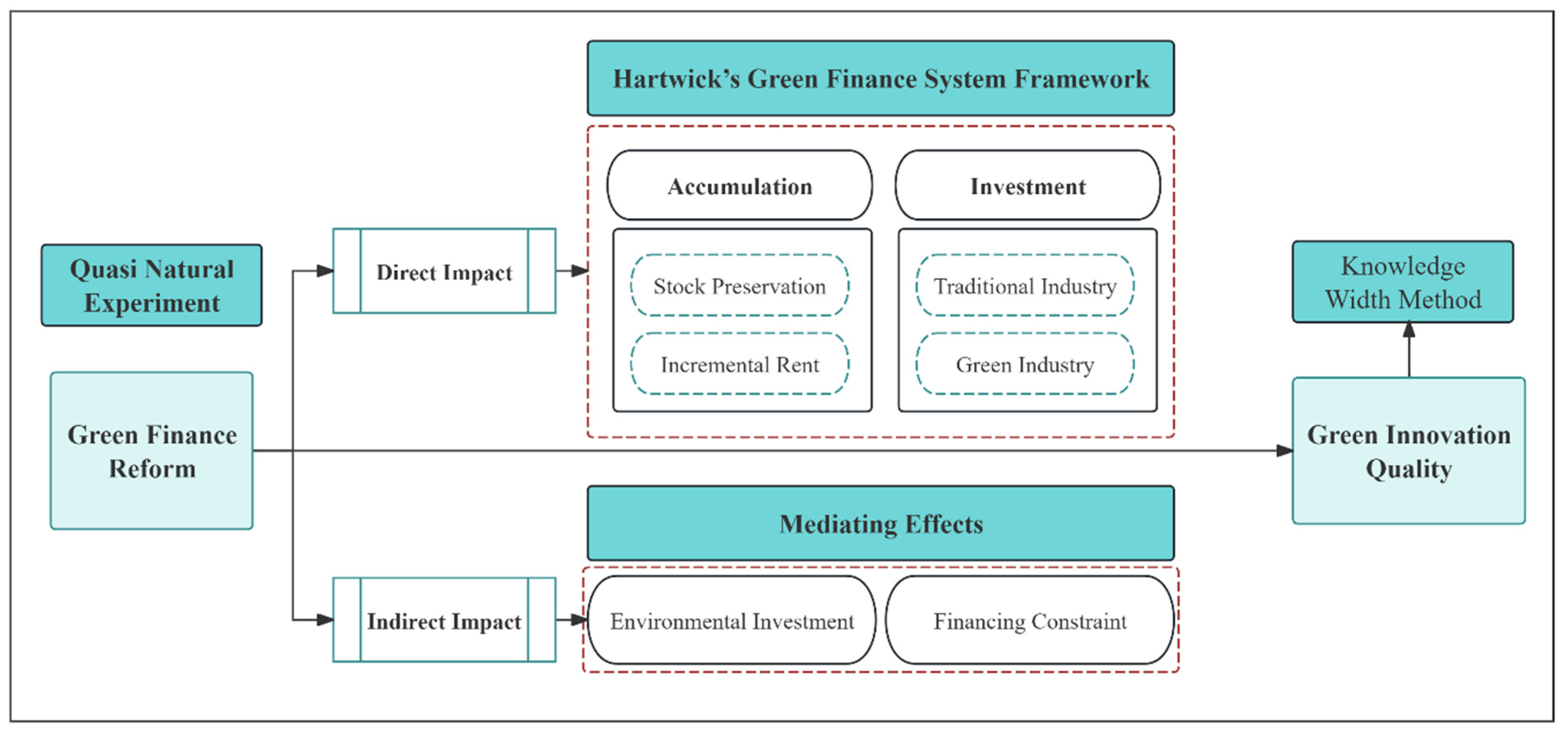

Specifically, an effective green financial market system should achieve cost optimization of the accumulation mechanism and maximize the benefits of the investment mechanism. This study takes Hartwick’s law as the core and proposes two operational principles of green finance: The first is to ensure that the stock of environmental resources does not decrease through an accumulation mechanism [

3,

8]. The second is to achieve effective replacement of environmental investment and environmental resources through investment mechanisms [

16,

17]. Based on this, we have constructed the framework of the green finance system in

Figure 2, providing a theoretical basis for how green finance can achieve both its stability and environmental sustainability simultaneously.

From a more essential perspective, Hartwick’s law not only emphasizes the importance of the sources and allocation of funds, but also endows micro-dynamics for the quality leap of green technologies in enterprises [

36]. Specifically, the accumulation mechanism provides a stable source of funds by ensuring that the scarce rent generated by environmental assets is used for environmental investment. The stability of this kind of fund provides solid financial support for enterprises to effectively carry out high-quality green innovation, thereby significantly improving the quality of green technologies [

25,

37].

However, most of the existing literature regards environmental policies as exogenous shocks and discusses how they can expand the total number of green patents, but neglects the quality of green innovation in enterprises. For instance, Li et al. [

24] found that command-based environmental regulations can stimulate an increase in the number of green patent applications. Meanwhile, the investment mechanism, through the incentive effect of the market, directs funds toward technologies and projects with the advantage of the marginal benefits of capital. This market-oriented system is conducive to the optimal allocation of resources and encourages enterprises to continuously improve their technology and technological quality through dynamic competition. In the green financial system, maximizing the efficiency of capital allocation means that resources will flow to innovative technology projects with the highest environmental and economic benefits, thereby promoting the green technological progress of the entire industry. Therefore, this paper is dedicated to exploring whether and under what conditions green finance can significantly enhance the quality of green innovation in enterprises [

10,

38].

We take Hartwick’s law as the logical starting point, combine local static equilibrium analysis and the Shephard lemma, and construct a mathematical description of how green financial policies enhance the GTQ, enriching the relevant literature on green finance and green innovation [

4,

8]. From the perspective of institutional theory, enterprises must make adaptive responses to external institutions to obtain legitimacy and resource endowments [

39]. Against the backdrop of the implementation of green financial policies, enterprises could adapt to government requirements to obtain green financial resources, making the production of green innovative products the production goal. According to the technical and sustainable characteristics of green innovation, the realization of the production goal requires the input of green production factors that meet the requirements of low-carbon transformation and technological research and development. The cost of green production factors can be regarded as the cost of environmental R&D investment. Based on the principle of minimizing production costs, enterprises only need to spend such costs when conducting green innovation, and the input amount is constrained by the accumulation of green financial funds and the efficiency of market resource allocation. Therefore, green factors can be regarded as quasi-fixed production factors, while capital, labor, and technological level are considered variable production factors. Now, taking the minimization of production costs as the decision-making criterion for the input of production factors, with a total of X variable factors and Y quasi-fixed factors, the variable cost function of the enterprise’s green innovation can be expressed as

where C represents the variable cost of green innovation, GTQ represents the enterprise’s green innovation quality,

(x = 1, 2, …X) is the price of the Xth variable element, and

(y = 1, 2, …Y) is the input quantity of the Yth type of “quasi-fixed” factor. According to Shepard’s lemma, the demand function of variable factor capital E can be represented by the quality of green innovation GTQ, the price of the variable factor

, and the price of the quasi-fixed factor

. This paper refers to the practice of Berman and Bui [

40] and selects the linear function E to represent it as follows:

where q represents the marginal impact of an enterprise’s enhancement of green innovation technology levels on the size of variable capital requirements, reflecting the variable factor demands brought about by an enterprise’s current promotion of green innovation. This paper assumes that γ > 0, that is, the relationship between the input of green production factors caused by green financial policies and variable factor capital is determined by substitution. We assume that G represents the green finance policy, and θ represents the marginal impact of the green finance policy on the changes in variable factor capital. If μ represents the influence effect of factors other than green finance policies, then the relationship between variable factor capital and policies can be expressed as

By differentiating Equation (3), the formula for the impact of green finance policy G on variable factor capital can be obtained:

Under the theoretical framework of Hartwick’s law, the fund accumulation mechanism provides a stable source of funds by ensuring that the scarce rent generated by environmental assets is used for environmental investment. Meanwhile, the investment mechanism, through the incentive effect of the market, directs funds toward technologies and projects with the advantage of the marginal benefits of capital,

. Therefore, assuming that the variable factor market is perfectly competitive, the prices of various variable production factors in the market will not change due to a certain producer or consumer, and green financial policies will not have an impact on the prices of variable factors, that is,

Then the formula for the quality impact of green innovation can be obtained as

where green finance policies use capital allocation as a policy tool, which can guide financing entities to achieve green transformation. Enterprises will respond to external systems to obtain legitimacy or the resources needed by the organization and carry out green transformation, that is,

.

reflects whether green activities and capital are complementary or substitutive. Generally speaking, the increase in green production factors (such as clean energy and environmental protection technologies) will directly lead to the reduction in traditional variable factor capital (such as highly polluting equipment and inefficient labor), that is,

< 0. Therefore,

, which indicates that green financial policies can promote the improvement of the quality of green innovation in enterprises.

3.2. Research Hypothesis

Existing research has broadly established a consensus regarding the “financing relief” function of green finance: its primary role is to drive the green transformation of the economy, achieve a dual rebalancing of economic growth and environmental sustainability, and alleviate the long-term funding gap associated with environmental investments [

3,

4,

7]. Financial instruments are instrumental in addressing the challenges related to long-term and stable capital inflows. The green financial system has demonstrated effectiveness in resolving capital shortages commonly encountered during the transition to a green economy [

33,

38]. Empirical findings from Rao et al. [

9] indicate that green bonds significantly reduce corporate financing constraints, thereby promoting an increase in green innovations. However, theoretical perspectives remain divided on the impact of green finance on the quality of corporate green innovation, with two dominant views: the “effective incentive theory” and the “ineffective incentive theory.” Some scholars argue that green finance policies have imposed stricter credit constraints on highly polluting enterprises, consequently suppressing their research and development activities [

29].

From the perspective of principal-agent theory, this paper argues that GF can provide positive incentives for corporate green innovation quality. First, discrepancies in utility functions between financial institutions and enterprises may give rise to managerial moral hazard, thereby exacerbating principal-agent problems. Owing to its distinctive environmental regulatory attributes, green finance can effectively mitigate such agency conflicts, thus playing a constructive role in promoting corporate green innovation [

41]. This paper develops the conceptual framework illustrated in

Figure 3. Second, as the green financial system continues to evolve, GF has emerged as a critical incentive mechanism for advancing the green economy [

20,

42]. In its initial stages, the green financial system was predominantly established under government leadership as a core element of global sustainable development strategies [

19]. However, due to the inherent presence of regional heterogeneity, green finance encounters practical challenges such as implementation difficulties, insufficient credibility, and inadequate regional policy support during its dissemination [

43]. The PZGFRI seeks to address these challenges by granting enhanced policy autonomy to pilot regions, enabling green finance policies to align precisely with local economic features, and customizing financial support programs for enterprises. This approach effectively facilitates corporate green transformation and enhances GTQ. Under this policy framework, each pilot zone has been able to construct a regionally tailored green financial system and actively develop green financial services [

7,

19]. Given that the business orientation of local enterprises often closely corresponds with regional economic characteristics, these pilot policies can directly address the key constraints enterprises face during the green innovation process, thereby significantly improving firms’ GTQ. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. The PZGFRI can improve enterprises’ green innovation quality.

Existing research suggests that the scale of environmental protection investment reflects the strategic priorities of enterprises in resource allocation [

44]. According to externality theory, environmental protection investments exhibit significant positive externalities, resulting in market-determined investment levels that are typically lower than the socially optimal level under spontaneous equilibrium. Under the guidance of government policies, social capital is more likely to support corporate environmental protection initiatives, thereby facilitating easier access to financing. Higher levels of environmental investment can stimulate corporate green innovation and consequently enhance GTQ [

29,

45]. For example, Cheng and Zhu [

46] found that increased environmental protection investment effectively encourages enterprises to engage in green technological innovation, thus improving the quality of such innovation. However, corporate environmental investment decisions hinge on a cost–benefit trade-off, aiming to minimize the total long-term costs associated with environmental investment and environmental tax payments. Unlike traditional long-term investments, environmental protection investments are characterized by externalities and high risk, and therefore require stable and sufficient external financial support. In the absence of accessible external financing, profit-maximizing enterprises may reduce their environmental investment. The establishment of a green financial system has effectively eased corporate capital constraints, created new sources of economic growth, and facilitated green transformation [

47,

48]. Therefore, the PZGFRI can provide financial support for corporate environmental investments, thereby promoting GTQ. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2. The PZGFRI improves enterprises’ green innovation quality by incentivizing firms to increase investment in environmental protection.

According to the financing constraint theory, due to the high-investment nature of green innovation itself, enterprises often encounter certain financing constraints when conducting green innovation [

6,

7,

49,

50]. As green technological innovation belongs to capital-intensive R&D activities, financing constraints have become one of the key factors restricting the improvement of enterprises’ innovation capabilities [

51,

52]. Existing research has found that green finance can significantly alleviate the financing constraints of enterprises and provide financial support for enterprise innovation [

20,

41]. For instance, Chen et al. [

41] found that green finance can change the financing costs of enterprises and thereby promote the simultaneous increase in the quantity and quality of the green innovation of enterprises. This study holds that the PZGFRI can effectively alleviate the financing constraints of enterprises and thereby promote their GTQ. On the one hand, the PZGFRI can effectively promote the innovation of green financial products within the jurisdiction. Under the impetus of this policy framework, various innovative green financial tools have been constantly emerging, injecting new vitality into the green financial system. This new type of financial supply can provide direct resource support for the green transformation. For instance, green credit can increase the channels for enterprises to obtain funds, broaden the financing approaches for their green transformation, and thereby alleviate financing constraints. In addition, green financial tools such as green funds and green insurance can guide private capital into the field of clean production, thereby stimulating green innovation. On the other hand, under policy guidance, local governments can more effectively introduce a series of green preferential policies that are beneficial to local enterprises [

53]. This can not only provide targeted fiscal and tax incentives to solve problems such as difficult financing for enterprises, long payback periods for technological innovation, and high repayment pressure, but also help enterprises increase their GTQ. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3.

The PZGFRI improves enterprises’ green innovation quality by reducing corporate financing constraints.

Existing studies have consistently pointed out that the incentive effects of green finance policies have significant heterogeneity [

54,

55,

56]. For instance, Fu and Zhao [

55] confirmed that state-owned enterprises benefited more prominently, while Gao et al. [

56] found that large-scale enterprises also enjoyed policy dividends. Under the framework of the PZGFRI, this “scale-ownership” disparity has been further magnified by the targeted optimization of financial resource allocation. Specifically, based on the hypotheses of “ownership premium” and “scale signal”, the implicit government guarantee attached to the state-owned background and the reliable mortgage assets of large enterprises jointly lower the information asymmetry and default risk premium of banks, enabling the two types of entities to obtain green credit at lower interest rates, for longer periods, and with more simplified guarantee procedures. This effectively offsets the high adjustment costs and long payback period required for green technological innovation [

55,

57]. Secondly, following the theory of resource allocation, state-owned and large enterprises, with their abundant human capital, technological reserves, and vertical integration capabilities, can rapidly internalize external green financing into a “research and development–production–market” collaborative chain, significantly enhancing the marginal output per unit of green investment [

54]. Secondly, large enterprises are subject to multiple reputation constraints from the media, the public, and regulators. Green transformation can not only reduce potential compliance and litigation costs, but also raise market valuations through “green reputation capital”, forming a positive feedback loop. In conclusion, PZGFRI, by allocating financial resources, has magnified the inherent endowment advantages of state-owned and large enterprises, resulting in a significantly higher improvement in the quality of their green technological innovation compared to non-state-owned and small enterprises. This has verified the “scale-ownership” heterogeneity effect of green financial policies. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 4.

The PZGFRI can promote the enterprises’ green innovation quality in state-owned and large enterprises.