1. Introduction

This essay seeks to critically examine whether the emerging model of capitalist organization, rooted in digital platforms, can serve as an effective instrument for promoting social and environmental sustainability—capable of addressing the profound challenges threatening human survival.

Today, platform capitalism has extended its reach across all sectors of the economy, becoming an integral part of the daily lives of most individuals with access to digital devices. According to the European Council, the platform economy was valued at approximately €3 billion in Europe in 2016. By 2020, this valuation had surged to €14 billion, a growth largely driven by the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, the sectors contributing most to this increase were taxi services and food delivery, which accounted for approximately 75% of the growth. During the first year of the pandemic, revenues from home delivery of meals increased by 125%.

One might assume that the end of lockdown measures and the resumption of pre-pandemic activities would have led to a significant decline in these services and a reversion to traditional business models. However, this has not been the case. For consumers and companies alike, these applications have become so embedded in daily routines that a return to previous practices appears improbable. In 2022, total revenues for these services reached $40.2 billion.

According to a study by Accenture [

1], the valuation of platform capitalism currently stands at approximately

$492 billion, with projections indicating growth to

$1.2 trillion by 2025. These figures underscore the extent to which conducting business without reliance on these technologies has become virtually unthinkable.

It is important to note that these data are partial, primarily capturing transactions involving tangible goods and services traded on digital platforms. As we will explore further, the development of platform capitalism increasingly influences technological, financial, business-to-business, and human-to-human relationships. The real-time collection, manipulation, and processing of data have become central to contemporary business practices. The value generated through these intangible activities is difficult to quantify but now permeates virtually every aspect of human activity.

2. The Digital Platform as Radical Organizational Innovation

Contemporary capitalism, especially in the new millennium, has been propelled by a fundamental innovation: the digital platform. This innovation has revolutionized and standardized the organization of the production and dissemination of goods and services.

There is an extensive body of academic literature surrounding the topic of digital platforms, which initially developed within the fields of business studies and management and later within media studies. The term “platform economy” refers to the recent transformations in production, distribution, labor, and consumption, primarily driven by technological advancements in Internet connectivity and the expansion of cloud storage. These changes have been analyzed in openly celebratory terms, such as the “digital revolution”, a concept popularized by the book Race Against the Machine (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2011 [

2]). In this work, the authors from MITs Sloan School of Management depicted a utopian landscape where machines, platforms, and people interact productively and harmoniously (Brynjolfsson and McAfee, 2016 [

3]; McAfee and Brynjolfsson, 2017 [

4]).

Simultaneously, and in light of the phenomenon of San Francisco-based startups, some scholars have adopted a more neutral approach. The key text, The Rise of the Platform Economy (Zysman, 2016 [

5]), sought to refine the terminology, arguing that terms such as “digital economy”, “creative economy”, “gig economy”, or “sharing economy”- though often used interchangeably - are neither sufficient nor entirely synonymous, and that some are overly idealistic or misleading. Within this framework, neutrality does not imply a purely positive stance; rather, it aims to critically examine the ongoing transformations. Nevertheless, the authors’ perspective revealed an underlying positive appraisal of the so-called “digital revolution” (Zysman and Kenney, 2018 [

6]). Indeed, a review of the literature on platforms shows a proliferation of the term “revolution,” as in “algorithmic revolution” (Zysman et al., 2013 [

7]), “platform revolution” (Parker, Van Alstyne, and Choudary, 2016 [

8]), and “the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” According to this perspective, the platform economy pertains to the capacity of new information technologies to facilitate the commercialization of social relationships. This process of monetization primarily occurs within services and involves digitalizing any human activity that potentially creates value—ranging from ride-hailing to food delivery. Consequently, the disruption theory, highly popular in business schools in the late 1990s, has been re-applied to platform enterprises, as their organizational structures enhance their ability to enable profitable transactions beyond traditional economic sectors (Christensen, Raynor, and McDonald, 2015 [

9]; Ozalp, Cennamo, and Gawer, 2018 [

10]).

By organizing increasingly larger sectors of our economic and social lives, these platforms and the firms associated with them aim to transform everyday interactions into potential sources of value. In contrast to the long-standing notion of ownership of means of production as a form of power during agricultural and industrial eras, the growing importance of digital intermediation—both in terms of economic power and sociopolitical influence—has become the primary instrument shaping economic hegemony today. From this perspective, the platform economy evolves into platform capitalism, as discussed in critical literature on platforms (Srnicek, 2016) [

11]. Building on this line of thought, it is important to highlight some critical contributions compiled in the volume edited by S. Mazzard, N. Cuppini, M. Frapporti, and M. Pirone (2024) [

12]. Additionally, relevant works include M. Casas-Cortés, M. Cañedo, and C. Diz (2023) [

13]; R. Boyer (2022) [

14]; and A. Buissink (2023) [

15]. Srnicek’s contribution approaches the issue from a more strictly economic standpoint.

According to Srnicek (2016) [

11], digital platforms exhibit four core characteristics:

They serve as intermediary digital infrastructures facilitating interactions among diverse user groups—consumers; advertisers; service providers; manufacturers; suppliers; and even physical objects. Some platforms also provide tools enabling users to develop their own products, services, and markets—embodying a dynamic learning economy driven by processes of learning through doing; usage; and interaction.

They depend on and benefit from network effects (connectivity). The larger the user base, the greater the potential for value creation through user activities. This explains the rapid and exponential growth and unprecedented capital accumulation of platform companies over relatively short periods, exploiting what are known as dynamic network economies.

They employ differentiated support and revenue strategies, including cross-subsidization. By offering free products and services, platforms can attract and retain a larger user base, thereby increasing activity within their networks (cumulativeness). Economic gains and losses are balanced across multiple lines of business, fostering sustained growth.

They actively engage users through attractive presentations of their offerings, with the primary goal of extracting additional data—an essential resource—about their users.

The transactional activity on these platforms involves the mediation of a third party—the platform and its owner—altering the fundamental structure of market exchanges. While demand and supply relationships at an aggregate level may still exhibit inverse correlations with price, the traditional law of supply is increasingly challenged. Market hierarchy and competitiveness are now more contingent upon the power exerted by digital platforms rather than solely on supply-side factors like barriers to entry.

A particularly notable development is the hybridization of supply and demand, exemplified by the concept of the ‘prosumer’ (Toffler, 1987 [

16]), which blurs the classical Marxian dichotomy between use value and exchange value. This shift signifies a broader redefinition of economic valuation, often referred to as the ‘economics of demand.’

Consequently, activities previously deemed ‘unproductive’—such as social cooperation, reproduction, leisure, education, and welfare—are increasingly recognized as vital components of value creation and accumulation within this paradigm.

2.1. The Hybridization of the Human and Mechanical Elements

Platform capitalism is embedded within a broader technological paradigm emerging from advances in biogenetics (the creation of artificial biological materials), machine learning algorithms, artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, robotics, and big data analytics. We are witnessing a process wherein the human becomes increasingly mechanized, and machines acquire more human-like capabilities.

This convergence challenges the Marxian distinction between ‘concrete labor’ (manual, productive work) and ‘abstract labor’ (the social form of labor expressed in value). Platform capitalism exemplifies this shift, representing a form of biocognitive capitalism.

Recent scholarly interest has focused on the so-called ‘profit paradox’ associated with platform capitalism (see, e.g., Eeckhout, 2021) [

17]. This paradox arises because, despite the proliferation of big data, algorithms, and cloud computing—technologies initially expected to reduce transaction costs and eliminate intermediaries—market concentration has instead increased. This runs counter to the long-held belief, dating back to the dawn of the digital revolution, that widespread ICT use would diminish the costs of market operations and facilitate decentralized exchanges.

The core of this paradox lies in the pervasive influence of digital platforms as new organizational forms of extracting value through data and content ownership—marking a technological leap beyond traditional ICT paradigms.

2.2. The Role of Financial Market in Money Creation, Financing, and as a Valorization Measure

While ownership of intangible assets such as data provides platforms with a strategic advantage, much of their recent growth in profitability and financial power derives not only from monopolistic or oligopolistic control over information flows but also from profits generated through the ownership and exchange of non-reproducible assets—such as securities; shares; and real estate—often fueled by share buyback strategies.

Capital gains arising from increases in asset values are frequently influenced by these buyback programs (see Lazonick, 2014 [

18]), which artificially inflate asset prices and attract additional investor demand. This process exemplifies a form of financial speculation driven by corporate entities, capable (within certain limits) of manipulating prevailing speculative conventions and risking the formation of market bubbles.

From a macroeconomic perspective, financial markets have become crucial sources of financing for current investments. They also influence income distribution through a distorted financial multiplier effect, which is exacerbated by the erosion of public welfare systems—including pensions; healthcare; and education. These dynamics serve to fuel the accumulation and exploitation of data and information by platform companies.

As of 2024, the six most valuable companies by market capitalization are all platform-based firms (see

Table 1). For instance, Apple’s valuation alone approaches, or slightly exceeds, the combined GNP of Italy (

$2.376 trillion) and the Netherlands (

$1.218 trillion).

The combined market capitalization of these six platform giants is comparable to China’s GNP of approximately $18.273 trillion in 2024.

Over the past five years, significant share buyback activity has redistributed corporate profits to shareholders [

19]:

Since share repurchases are financed through retained earnings, their net effect on shareholder value is broadly equivalent to distributing those earnings as dividends, aside from tax implications.

Dividends and share buybacks are two sides of the same coin. They represent complementary mechanisms for distributing corporate profits. Since share repurchases are funded through retained earnings, their net economic impact on shareholders remains equivalent to dividend distributions—excluding tax implications. This approach aligns with neoclassical principles rooted in agency theory (Jensen and Meckling [

19], 1976), which posits that maximizing shareholder value is essential for optimizing a firm’s total value.

We observe the “becoming rent” of profit, a process that reconfigures income distribution among rents, profits, and wages (Vercellone [

20], 2013).

3. The Metamorphosis of the Capital-Labor Relationship: Life-Value as a Source of Surplus Value

Following this introduction to platform capitalism as an expression of biocognitive capitalism, we now examine the evolving nature of labor and its implications for social and environmental sustainability. Two key points merit emphasis.

3.1. A New Concept of Productive Activity and the Subjectivation of Labor

Under platform capitalism, the valorization process exploits human biocognitive and relational capacities, commodifying life itself. As individuals are intrinsically social, their cooperative interactions and social reproduction—dynamic; heterogeneous; and non-scarce—become central to production.

Human life is thus fragmented into distinct temporal categories:

Labor (labor): Time conventionally deemed “productive.”

Work (opus): Time dedicated to personal aspirations, desires, or creative pursuits.

Idleness (otium): Time spent on social relations, leisure, communication, or contemplation.

Rest (quies): Time allocated to survival activities (sleeping, eating, recuperation).

In the Fordist era, only labor was remunerated as “productive.” Cognitive capitalism (1990s onward), reliant on network and learning processes, began integrating elements of work and otium into value creation, blurring the lines between employment types (e.g., hybrid contracts) and work-life boundaries. Today, in platform-driven biocognitive capitalism, every aspect of daily life—whether as producer or consumer—is subsumed into value generation.

3.2. A “New” Labor Market

Platforms redefine labor markets by mediating capital-labor relations. Two dynamics emerge:

Formal Separation: Third-party intermediaries create ambiguous employment arrangements (e.g., gig work), fostering precarity and exploitation.

Hybridization: Traditional distinctions between capital and labor dissolve amid technological advancements.

The first case gives rise to distortive forms of employment, which are gradually regulated by law through the introduction of various types of employment contracts. This phenomenon of precarious work emerges and develops, fostering new forms of subjugation and exploitation.

Regarding the second case, we are witnessing the emergence of a new technological paradigm that follows the era of ICTs. This paradigm is based on genetic technologies, which explore the horizon of transforming humans into becoming machines, and on regenerative algorithmic technologies, which move towards the horizon of transforming machines into becoming human (see

Section 2.2).

In this context, the relationship between labor and capital is increasingly characterized by the use of vital faculties, both as essential elements of labor and as the capacity to modify an increasingly intangible factor of production—capital.

We are observing a new productive and organizational landscape in which traditional instruments of capitalism are undergoing profound transformations, both in the realm of market exchange and in the nature of the capital-labor relationship.

3.3. Is a New Technological Paradigm and Valorization Process Emerging?

According to Kondratieff’s long-wave theory [

21], the time is ripe for significant change, and several signs point in this direction. Since 2003, the decoding of the human genome has opened vast possibilities for manipulating individual life and reproduction, as well as the potential to artificially create human tissues and combine them with elements of equally artificial machines. We are thus witnessing the emergence of a new biopolitical technology, or ‘biotechnology’.

The development of Generation II (regenerative) algorithms is enabling an unprecedented process of automation in human history. When applied through information technology and nanotechnology to machine tools, these algorithms can transform them into increasingly flexible and adaptable tools—so much so that they begin to assimilate human sensory potential.

Alongside these radical product and process innovations, organizational change is also evident. Digital platforms inaugurate a new organizational model, just as the scientific organization of labor marked the birth of Fordism. The platformization of contemporary capitalism represents the new hierarchical form of biocognitive capitalism, which was necessary to establish a new economic order based on large corporations. This shift followed a period at the end of the last century when the battle for free access to ICT was still ongoing. The spread of platforms signified the victory of that battle, leading to the consolidation of the capitalist order: The expropriation of common wealth and the privatization of life itself.

Platform capitalism is relatively abundant—particularly in terms of immaterial production that relies on knowledge (which is not scarce) and virtual space (which tends to be infinite). However, significant constraints remain concerning environmental sustainability [

22].

In both cases, a traditional theory of value based on scarcity loses relevance. Knowledge and space—hence learning and networking—are artificially made scarce; whereas goods that are genuinely scarce require public or common governance beyond private ownership.

The only theory of value that still makes sense is one rooted in human activity. However, this activity is no longer unambiguously expressed through the concept of ‘productive labor,’ as is now recognized. It is necessary to shift from the labor theory of value to a theory of ‘life-value’ (Fumagalli-Morini, 2011) [

23].

A theory of life value presents numerous challenges, starting with the issue of measurement. Regarding platforms, one specific value that can be identified is network value—the transformation into exchange value of the information; knowledge; data; and other resources that each of us provides to platforms as use value [

24].

The new algorithmic technologies of big data enable the development of ‘business intelligence’ [

25], a technique for exploiting the data collected by platforms. The network value is made possible not only through the expropriation of data from ‘prosumers’ but also through the activity of click workers who ‘train’ regenerative algorithms [

26].

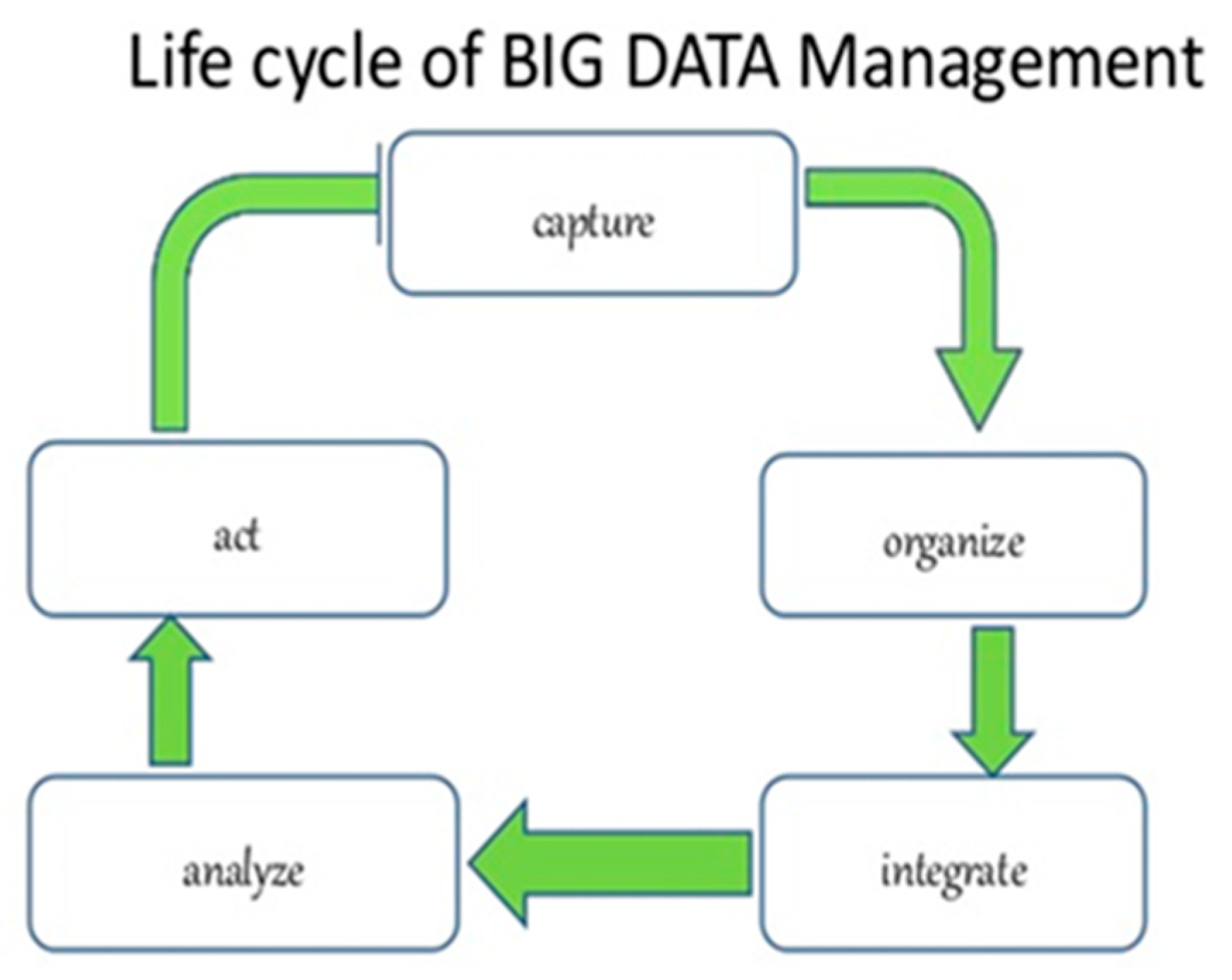

Figure 1 describes the process of leveraging big data, A critical focus lies on the operations of organizing and integrating data, which have achieved heightened sophistication in recent years due to advancements in second-generation algorithms. These operations form the foundation for generating network value—a production-centric aspect of exchange value. Meanwhile, “analysis” and “action” represent its commercialization, i.e., the monetary realization of value in output markets.

This dynamic defines a new composition of capital, increasingly automated in dividing data according to its potential commercial utility. Central to this process is the participation of users—now reconfigured as prosumers—who unwittingly supply raw material (their data) to capitalist production through their engagement with platforms. These platforms, whether oriented toward information, communication, gaming, or social interaction, subsume this “raw material” into productive capitalist systems.

While human relations, social cooperation, collective intelligence, and social reproduction today express the “common” as a mode of production [

28], they simultaneously underpin the “communism of capital”. That is capital’s capacity to subsume and capture the lifeworld of individuals [

29]. Platform capitalism derives value from a production process where the “raw material” is human life itself. Crucially, this material is largely provided

freely, as it originates in activities aimed at generating

use value.

The “secret” [

30] of accumulation lies in transforming use-value (concrete labor) into exchange-value (abstract labor). Concrete labor, per Marx, produces use-value through qualitatively distinct activities (e.g., daily life generating data via social interactions). Abstract labor, however, quantifies human labor-power stripped of qualitative specificity; it determines value via socially necessary labor time under prevailing technological conditions.

In platform capitalism, abstract labor manifests as the organization and integration of data—tasks performed by salaried employees. The “raw material,” however, remains concrete labor. The unstructured data of everyday life. This duality generates network value, which augments the labor value required to transform data (initially use-value) into exchange-value.

In the valorization of big data, the process of subsumption thus divides into two parts and undergoes a transformation.

In the first phase, a process of original accumulation occurs, extending the production base to encompass entire lifetimes. However, this participation is typically passive and non-remunerated, without formal recognition or subjectivity—meaning we cannot truly speak of genuine formal subsumption at this stage.

In the second phase, organized labor, comprising both salaried and precarious workers, often working from home, known as clickworkers—takes over; performing processing tasks and other activities according to more traditional notions of real subsumption.

Therefore, both formal and real subsumption coexist and can influence each other. We can refer to this process of subsumption, characteristic of platform capitalism as an organized form of bio-cognitive capitalism, as life subsumption [

29,

31,

32].

4. The Meaning of Labor Activity

The cognitive capitalism of the 1990s—the net economy—assigned value to life through the labor process. Work performance was organized to exploit the full potential of learning and network economies. The labor relationship tends to individualize and increasingly rely on cognitive, emotional, and relational faculties of the human being. It is no surprise that, at this stage, we are also witnessing a process of feminization of labor [

33]. Diversity broadens the heterogeneity of labor performance and serves to enhance capital appreciation.

Labor becomes less routine and more engaging while simultaneously differentiating itself. This gives rise to flexibility and fragmentation, which soon become the hegemonic conditions: The precariousness of labor. This precariousness is increasingly existential, structural, and widespread, but it manifests within a variety of spaces—not just factories or offices; but everywhere—with increasingly fluid and unpredictable schedules. It remains within organized processes and is thus remunerated, often in differentiated ways.

With the shift to bio-cognitive capitalism and its expression in platform capitalism, life itself begins to be directly valorized—without necessarily passing through the mediation of recognized or regulated labor activity. The concepts of otium (leisure) and opus (work) start to directly enter the process of valorization, but only labor remains acknowledged as a productive activity.

As a result, productive activity tends to diminish, becoming invisible, with only a portion being formalized and remunerated. Job insecurity increasingly gives way to the gratuity of productive activity. Labor, therefore, loses its traditional meaning. Life, in its complexity, becomes the central source of added value—independent of labor.

This process is more widespread as the relationship between capital and labor becomes less and less distinguishable. However, it is not that labor turns into capital. The concept of human capital—so central to mainstream economics and celebrated as capitalism’s ability to recognize individuals in their essence—begins to serve as an ideological barrier. It reinforces and solidifies the precarity trap by manipulating culture and knowledge.

This precarity trap is reinforced through social control devices and individualistic, self-referential mechanisms—amplified by platforms that explicitly manage; convey; select; and exploit social relations. It tends to turn into a trap of promise and gratuity [

34].

There are no longer truly unoccupied individuals—those who are either unable or unwilling to participate in the creation of (added) value and are therefore unproductive from the perspective of accumulation. Far from the end of labor, we now face a form of labor with no clear conclusion. The dramatic dichotomy today is between those who produce value—whose productivity remains unrecognized or unremunerated—and those who perform activities recognized as productive and therefore compensated in some way. Capital subsumes life activities, rendering labor increasingly invisible.

5. About Sustainability

5.1. Social Sustainability

Let us first consider social sustainability. Platform capitalism negatively impacts income distribution, favoring growth in stock market capitalization at the expense of labor income. The proportion of productive life that is not formally recognized as such tends to increase, promoting oligopoly and monopoly dynamics, often reinforced by ownership of intellectual property rights. Informal and precarious work arrangements are on the rise. The worsening income distribution has adverse effects on national aggregate demand, especially in contexts lacking sufficient export offsets.

While short-term financial and technological multipliers may sustain high growth rates, there is a risk that, in the medium term, instability may develop within financial markets—due to the formation of speculative bubbles—and within real markets—due to insufficient effective demand. This situation is further complicated by geopolitical instability, as the transition from a unipolar global order centered on the US economy to a multipolar one remains unresolved.

Therefore, there is a pressing need for policy interventions aimed at equitable distribution and correcting distortions created by the economic hierarchy imposed by digital platforms. Concerning income distribution, it is essential to resolve the paradox of a form of productive activity that encompasses entire human lives, even as paid employment becomes increasingly invisible.

Recognizing that everyone is productive implies the necessity of an unconditional basic income (UBI) as a primary income—an instrument of remuneration that acknowledges the productivity of life subsumed by capital. As formal labor diminishes, the importance of UBI grows. Currently, welfare policies that recognize the need for a basic income often perform so as a means to facilitate labor market participation (see next para.). However, unconditional basic income should be considered a fundamental right, independent of active labor policies.

From the supply side, it is important to recognize three distinct platform models: traditional profit-driven platforms, open commons, and platform cooperatives [

35]. The first, most widespread and conventional, aims at profit generation—often through extractive means—and typically neglects the externalities of their activities (Cano, M.R.; Espelt, R.; Morell, M.F., 2024) [

36]. Despite their dominance, alternative models exist that align more closely with sustainable development goals (SDGs), such as digital commons and cooperatives.

One promising alternative to platform capitalism is platform cooperativism, which adopts principles of cooperativism and the values of the Social and Solidarity Economy (SSE) (Scholz, 2016 [

35]). The SSE offers a potential model to reshape digital platforms, combining best practices from current systems—like technological efficiency and knowledge—with community-centered goals (RIPESS, 2015 [

37]). Platform cooperatives can be organized by foundations, associations, cooperatives, or even social enterprises with a mission-driven focus (Scholz, 2016) [

35].

The third model involves open commons platforms, which go beyond cooperatives by promoting the sharing of data and knowledge through open licenses and Free Libre Open Source Software (FLOSS) (Bauwens & Kostakis, 2015 [

38]; Benkler, 2006 [

39]; Morell, 2010 [

40]). These platforms tend to be more sustainable than traditional profit-oriented platforms because they are not solely driven by profit motives.

However, cooperative and open commons models face challenges related to economic sustainability. They risk falling into the “marginality trap,” where activities sustain themselves only on a small scale within niche markets. If such initiatives expand and succeed, they may come under pressure from market commodification, which can undermine social sustainability for the sake of economic viability.

A final important issue to address is digital inequality, which is increasingly a significant social factor. The digital divide leaves segments of the population with limited or no access to information and digital devices, thereby restricting their social opportunities. Limited access to modern digital technologies exemplifies digital inequality. Ensuring digital equality is crucial in today’s society, but policymakers have yet to institutionalize the right to internet access. The failure to perform so risks creating a new form of inequality—one that prevents many individuals from accessing vital information. The right to digital connectivity should be recognized as a fundamental human right.

5.2. Environmental Sustainability

Digital platforms can offer numerous benefits for environmental sustainability. Digitization reduces the consumption of physical resources by dematerializing processes and enabling electronic sharing of information and documents. Additionally, they can facilitate the transition to a circular economy by promoting the sharing, reuse, and recycling of goods and services. For example, in office environments, the use of printed paper has decreased, while e-books and mobile devices such as e-readers have lessened the environmental impact associated with book production and related pollution. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the widespread adoption of smart working reduced transportation needs, contributing to a decrease in greenhouse gas emissions.

An illustrative example of digital technology supporting sustainability is Walmart [

41], a US multinational retailer with 11,847 stores across 27 countries. Walmart has implemented various digital transformations aimed at reducing waste and energy consumption. The deployment of integrated IoT sensors and shelf-scanning robots has demonstrated energy savings, while the ability for customers to place orders directly from home has lowered transportation-related CO

2 emissions. However, despite these technological advances, Walmart’s reputation regarding social sustainability remains poor. The Food Chain Workers Association (FCWA) reports that Walmart engages in systematic exploitation of migrant workers both in the US and globally [

42]. This highlights that environmental sustainability does not always align with social sustainability.

Digital platforms also enhance access to sustainability information. Consumers can now access data on product provenance, production practices, environmental impact, and other relevant factors. This transparency empowers consumers to make more informed choices, rewarding companies that adopt sustainable practices and encouraging the market to shift toward greener alternatives. These platforms also foster collaboration and resource sharing—through car-sharing; bike-sharing; and shared housing—which optimizes resource use and promotes efficiency; thereby supporting sustainability goals.

However, despite their potential, digital technologies also pose significant environmental challenges. The widespread use of digital products has overshadowed their polluting impacts, especially regarding their production, use, and disposal. The telecommunications sector, for instance, has a substantial environmental footprint. According to data from Boston Consulting Group (BCG) [

43], by the end of 2024, this sector contributed approximately 3% of global CO

2 emissions—more than twice the emissions of the aviation sector; which accounts for less than 2%. Given the rapid growth in data consumption, projections indicate that the sector could be responsible for up to 14% of global CO

2 emissions by 2040.

The environmental impact of streaming services is also significant. The increased use of smartphones, tablets, and streaming platforms like Netflix and YouTube has led to higher energy consumption, a trend accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused a surge in internet traffic and video streaming.

Furthermore, the expansion of big data and cloud computing industries has resulted in enormous data storage requirements in large, energy-intensive servers. The energy needed for data processing and storage adds to the environmental footprint of digital activities. A UN report [

44] highlights that in 2022, less than a quarter of the 62 million tons of e-waste generated was recycled; the situation remains dire. E-waste contains valuable materials and hazardous substances, and most discarded devices end up in residual waste, often incinerated or shipped to countries in Africa and Asia, causing severe water and air pollution and negatively impacting local communities’ health.

Given these contrasting effects, it is clear that digital transformation holds immense potential for achieving environmental sustainability goals. However, it also presents numerous challenges that technology companies must address. With the right tools, it is possible to foster a circular economy, reduce emissions, and promote the adoption of green and renewable technologies. This calls for a reassessment of policies at the global and national levels to integrate digital innovations across sectors effectively.

6. Preliminary Conclusions

Contemporary capitalism has commodified aspects of life that were previously non-commodified, among which is the human capacity to establish social relationships. This phenomenon is evidenced not only by the essays presented here but has also been critically examined within social media studies with significant attention. For example, José van Dijck [

45] has demonstrated how major contemporary social media platforms have evolved from initial stages that promoted forms of social aggregation to later phases—both technologically and algorithmically—driven by the imperative of accumulation; which involves commodifying social aggregation itself; initially made possible in the early stages. In this process, which precedes the broader process of subsumption of social life under capital, spaces for resistance can nonetheless be opened.

For instance, in the food delivery sector, riders’ practices constitute a form of daily “algorithmic resistance” (Woodcock, 2021 [

46]). This resistance manifests across streets, squares, social media, WhatsApp groups, and during waiting periods, when the digitalization of managerial functions via the app creates spaces largely free from direct managerial oversight. Confronted with geolocated control and opaque platform management—whose algorithms appear to operate at a distance; functioning as neutral and objective “black boxes” (Fernández and Soliña Barreiro, 2020 [

47])—couriers develop networks of “workplace solidarity” based on mutual support (Tassinari and Maccarrone, 2020 [

48]). This solidarity embodies the resistance of individuals who fear punishment, deactivation, isolation, or non-payment as consequences of their active participation in protests and collective actions against the platforms (Popan, 2021 [

49]; Yu, Treré, and Bonini, 2022 [

50]). These three forms of resistance constitute a continuum.

Simultaneously, digital platforms can facilitate greater environmental sustainability by promoting the dissemination of circular economy practices based on the “three Rs”—Reduce; Reuse; and Recycle. In this domain, opportunities to develop alternative models are broader than those explored through sharing economy experiments, which have often degenerated into practices of social washing.

A further final consideration concerns the need to redefine the boundaries of a new welfare system capable of addressing the transformations induced by platform capitalism. In platform capitalism, labor policies and social policies are inextricably linked. The distinction between labor time and lifetime tends to disappear with the precarization of labor. Platform capitalism exploits life itself as a relational commodity, producing value through social interactions. Neoliberal governance ensures that every act of existence is subjected to valuation. The remnants of welfare, as inherited in Europe, are increasingly suffocated by processes of extraction and exploitation. Therefore, it is time to update the concept of welfare to make it suitable for the precarious condition prevalent today, respecting gender, ethnic, and educational differences, with the aim of ensuring community well-being. In this regard, we speak of a Commonfare [

51]—a new welfare system designed to enhance quality of life; promote self-determination; and enable the exercise of the right to joy.

In Fordist capitalism, social services such as education, training, social security, care, and health also facilitated wealth redistribution between capital and labor. Public policies, as providers of these services, aimed to maintain social cohesion, ensuring that workers’ purchasing power supported mass consumption and that profits remained sufficiently high to sustain mass production. This social contract did not encompass the entire population but was limited to the “productive classes” (in the Marxian sense): Women and populations from underdeveloped territories—sources of immigration—were excluded. Women guaranteed the free reproduction of the workforce, while populations in less developed regions kept labor costs low.

With the proliferation of neoliberal policies, welfare institutions have increasingly become “capitalized”. Most notably, they have directly entered into the economic management of the private market. The Keynesian-style public welfare, no longer sustainable under the constraints imposed on public budgets, has gradually been replaced by forms of Workfare. Unlike universal social assistance systems (such as the Keynesian model), Workfare is only accessible to those with the financial means to pay for it. It is a self-financed welfare system, similar to most of the current European pension systems, which supports the privatization of healthcare, education, and social security. Workfare operates in conjunction with the so-called “principle of subsidiarity”, according to which the State can intervene only when objectives cannot be satisfactorily achieved by the private market.

As a consequence, the debate on welfare oscillates between the idea of a welfare aligned with neoliberal Workfare (more or less accompanied by subsidiarity) and nostalgic defense of the Keynesian state welfare model. In both cases, this conception of welfare fails to recognize that today welfare is a mode of production and, as such, should address the two main elements characterizing the current phase of bio-cognitive capitalism:

Precarity and debt as devices of social control and domination, capable of fueling the vital subjugation of labor to capital;

The reappropriation (in terms of distribution) of wealth stemming from social cooperation and the general intellect.

It follows that, in this context, a redefinition of welfare policies should be able to overturn the foundation of today’s bio-cognitive accumulation: The precariousness of life and social cooperation as sources of value. It is necessary to remunerate social cooperation and foster alternative forms of social production. The Commonfare proposal seeks to provide a response commensurate with these challenges.

Commonfare is thus based on two main pillars. On one side, it guarantees unconditional income continuity—independent of employment status; social or professional condition; or citizenship—complementing any other form of direct income as remuneration for productive social cooperation that underpins value creation and is today expropriated for profit and private rent. On the other side, it ensures access to material and immaterial common goods, enabling full and free participation in social life through the free use of environmental and natural commons (water, air, environment) and immaterial commons (knowledge, mobility, sociality, currency, and primary social services).

On one side, if adequately developed, the circular economy can lay the groundwork for the ecological sustainability of platform capitalism. On the other side, the Commonfare proposal offers a viable response to the challenges of social sustainability.