1. Introduction

The previous development model oriented toward economic growth has led local governments to neglect environmental protection, causing pollution issues in the atmosphere, soil, and other domains. Among these, watershed water pollution requires systematic governance due to its transboundary nature, fluidity, and externality characteristics. Watershed ecological compensation, as an institutional arrangement aimed at protecting and sustainably utilizing ecosystems through primarily economic means to regulate stakeholders’ interest relationships [

1], has gained widespread attention for its effectiveness in addressing watershed water pollution. The “Regulations on Ecological Conservation Compensation” implemented on 1 June 2024 marks a significant advancement in the legalization process of China’s ecological protection compensation system, signaling the transition of China’s ecological protection compensation mechanism from localized pilot programs to a new stage of institutional standardization. As China’s first cross-provincial watershed ecological compensation pilot project exploring multi-stakeholder collaboration involving governments, enterprises, social organizations, and the public, the Xin’an River watershed has not only provided crucial experience for the formulation of the regulation but also become a vital sample for testing the effectiveness of multi-stakeholder mechanisms post-implementation. The Xin’an River Basin’s practices have provided pivotal empirical experience for the regulation’s formulation, with their innovative approach gradually evolving into a universal “Chinese model” that offers replicable and scalable institutional references for addressing cross-regional ecological governance challenges. This paper adopts the Xin’an River as a case study to analyze the interactive relationships among multiple stakeholders in cross-provincial ecological compensation. It serves as practical verification of the regulation’s “multi-party collaboration” principle and provides theoretical support for the transition from policy to institutionalization in ecological governance, contributing to the construction of a modern Chinese-style ecological governance system.

Theoretical research on ecological compensation originated from the exploration of ecosystem service functions and value [

2]. By regulating the supply–demand balance of ecosystem services, ecological compensation can alleviate conflicts between ecological protection and economic development, thereby enhancing natural resource management efficiency [

3]. Domestic and international research on watershed ecological compensation is abundant, generally categorized into two types: ecological compensation system evaluation research and ecological compensation system design research. In ecological compensation evaluation research, scholars primarily focus on whether ecological compensation achieves its objectives, namely ecological environment improvement. Existing studies suggest that watershed ecological compensation can positively improve and protect the ecological environment, including by reducing watershed water pollution [

4,

5].

Beyond the primary objectives of ecological compensation, scholars have also noted its economic and social value. However, existing research shows no consensus regarding its economic value. Some studies suggest that the watershed ecological compensation promotes economic growth in compensated regions [

6], with significant poverty reduction effects [

7]. In the long term, ecological compensation mechanisms demonstrate notable effects in alleviating poverty [

8]. Meanwhile, some scholars argue that ecological compensation hinders regional economic development [

9,

10]. Ecological compensation system design research has also attracted significant scholarly attention, focusing on compensation standards, compensation methods, and participating entities. Regarding compensation standards, existing studies measure them through market-based and non-market-based approaches. Market methods determine supply–demand equilibrium points through market mechanisms, including the opportunity cost [

11] and income method [

12]. Non-market methods establish compensation standards through supply costs or willingness to pay [

13]. Both approaches have their respective advantages and disadvantages. To ensure scientific rigor and accuracy in measurement, some studies combine the strengths of multiple methods. Regarding compensation methods, traditional approaches are regarded as effective [

14], though certain issues persist. Some studies propose improvement measures accordingly [

15], while others suggest that market-based compensation methods and diversified approaches can adapt to broader regions [

16] and address more diverse scenarios.

The subject of watershed ecological compensation has also garnered substantial attention. Regarding participating entities, scholars have reached a consensus on establishing a multi-stakeholder ecological compensation system. From the theoretical perspective of national governance. Ansell and Gash agree that such governance issues necessitate equal and voluntary negotiations and consultations among governing bodies [

17]. Sheng J. et al. emphasized the importance of integrating market participation with government intervention [

18]. Yisheng Ren et al. introduced the concept of institutional “stickiness” into the scale political theory and analyzed the characteristics and mechanisms of government subject game behavior in the process of implementing ecological compensation in the Xin’anjiang River Basin [

19].

While the existing literature acknowledges the importance of multi-stakeholder participation, there remains a lack of in-depth analysis regarding how different entities can effectively collaborate and form synergies. This study focuses on the multi-stakeholder participation mechanism within cross-provincial watershed ecological compensation systems. This perspective further investigates the collaborative relationships among different actors including governments, markets, the public, research institutions, social organizations, and communities, thereby addressing the gap in existing research regarding inter-stakeholder interaction mechanisms.

2. Research Location and Data Sources

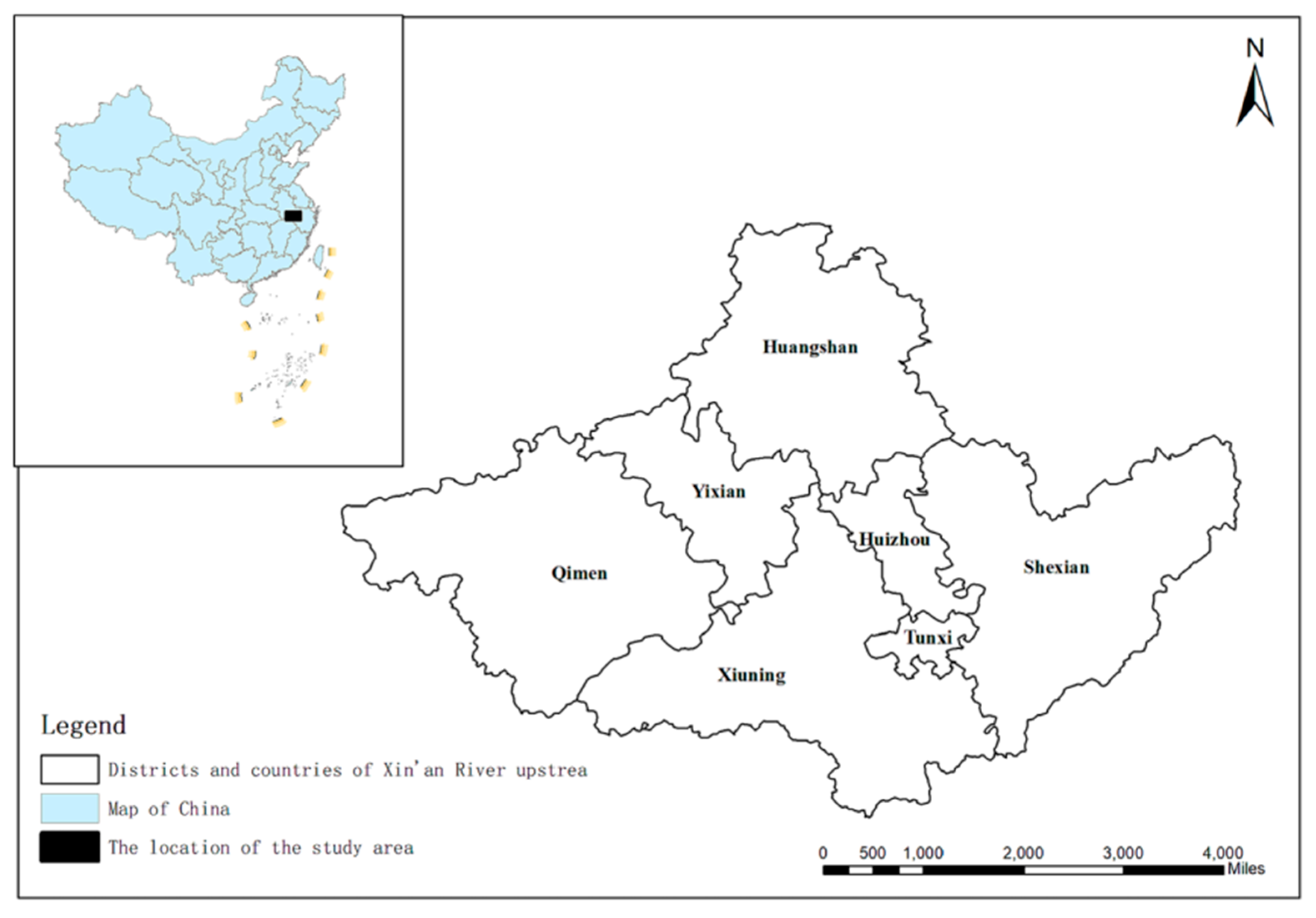

The Xin’an River, historically known as Zhejiang or Hui Port, traverses the present-day Anhui and Zhejiang Provinces. Originating from Fengcun Township in Xiuning County, Huangshan City, Anhui Province, it flows through Xiuning County, Tunxi District, Huizhou District, and She County before entering Chun’an County of Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, ultimately converging into Qiandao Lake. With a total length of 373 km and a watershed area exceeding 11,000 square kilometers, its mainstream spans approximately 242.3 km in Anhui Province and 116.7 km in Zhejiang Province. Overview map of the Xin’an River Basin sketch map (see

Figure 1). The terminal reservoir Qiandao Lake, long renowned as an important water source for both provinces, has experienced severe water quality deterioration since 1998, causing significant challenges for Zhejiang Province. Approximately 70% of Qiandao Lake’s annual average inflow originates from the Anhui section of the Xin’an River watershed. Consequently, ecological protection in the upstream region critically impacts downstream production and livelihoods.

However, Huangshan City in the upstream area faces economic development needs that inevitably generate environmental pollution. This dual challenge of balancing downstream water quality requirements with upstream economic growth has become a pressing issue for both provinces and relevant national authorities. Zhejiang and Anhui Provinces initiated exploration of the Xin’an River watershed’s ecological compensation mechanisms in 2004. Under the guidance of the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, they launched China’s first cross-border watershed ecological compensation pilot program in March 2011. By 2024, three rounds of the Xin’an River ecological compensation pilot program had been completed. In June 2023, the two provinces signed the “Agreement on Jointly Building the Xin’an River-Qiandao Lake Ecological Protection Compensation Demonstration Zone”, marking the commencement of the fourth pilot phase.

As China’s first pilot project for cross-provincial eco-compensation, the Xin’an River Basin’s application of multi-stakeholder collaborative governance demonstrates pioneering, representative, and significant policy value. It pioneered a comprehensive collaborative framework featuring government leadership, corporate responsibility, social organizational support, and public participation. This provided crucial experience for formulating the “Regulations on Ecological Conservation Compensation”; subsequently, it became a key testing ground for evaluating the real-world effectiveness of the multi-stakeholder mechanisms outlined in the regulations. Through long-term implementation, this “Xin’anjiang Model” has effectively addressed cross-jurisdictional governance challenges, significantly improved the ecological environment, and promoted green transformation, offering a replicable Chinese approach for basin-wide collaborative governance both nationally and globally.

The primary data for this study were obtained from the official websites of the Huangshan City and Hangzhou City governments, supplemented by field investigations conducted by the authors in Huangshan City, Anhui Province, during July 2024. Utilizing these data, this paper examines the background and current status of multi-stakeholder collaborative governance in the ecological compensation practices of the Xin’an River watershed, while analyzing the internal mechanisms of the watershed ecological compensation system from the perspective of multi-stakeholder governance.

4. Exploration of the Participation Mechanism of Ecological Compensation in the Xin’anjiang River Basin

The multi-stakeholder participation mechanism in ecological compensation enhances operational efficiency by reconstructing relationships among governments, enterprises, the public, research institutions, social organizations, and communities. This mechanism fully leverages stakeholders’ comparative advantages, culminating in the establishment of a coordinated framework for the Xin’an River watershed featuring government leadership, public engagement as the main driving force, market and social organization participation, research institutions providing technological empowerment, and rural communities offering foundational support, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

4.1. Government: Leader in Ecological Compensation

A review of the history of ecological compensation implementation in the Xin’an River Basin reveals that the government has played a leading role throughout the process. For instance, the central government has been responsible for policy formulation, macro-level regulation, supervision, and the evaluation of local government implementation, while also providing financial compensation. Through the development and implementation of relevant policies—such as the Implementation Plan for the Pilot Program of Water Environment Compensation in the Xin’an River Basin—the central government has offered scientific guidance and strategic direction for ecological compensation work in the basin. Additionally, it has allocated substantial fiscal resources, contributing several hundred million yuan annually for systematic ecological protection and restoration in the Xin’an River region, thereby laying a solid foundation for the successful execution of compensation initiatives.

Local governments, on the other hand, have been tasked with the concrete implementation and execution of specific projects, engaging in ongoing practical exploration. A collaborative yet mutually constraining relationship has emerged between the governments of Huangshan City and Hangzhou City, characterized by joint supervision and reciprocal incentives. Zhejiang Province and Anhui Province have jointly established a horizontally structured ecological compensation mechanism based on “performance-based water quality agreements.” As one of the local governments, Zhejiang Province has contributed CNY 100 million annually since the first pilot phase in 2012, increasing this to CNY 200 million in the second phase (2015–2017), and maintained this amount in the third phase (2018–2020), while also exploring market-oriented compensation mechanisms such as green funds and public–private partnerships (PPP models). Refer to

Table 2 for further details.

Additionally, Hangzhou has invested substantial resources in constructing wastewater treatment facilities in Chun’an County (lower Xin’an River), effectively reducing pollutant inflows into Qiandao Lake. Through nine key industrial collaborations with Huangshan City, Hangzhou has committed cumulative investments totaling CNY 21.367 billion (2020–2022), focusing on green industries and eco-agriculture partnerships. Notable examples include Hangzhou enterprises participating in Huangshan’s spring water fish farming and organic tea plantation projects, facilitating ecological product value realization. Huangshan’s municipal and county governments have enacted environmental protection regulations for the upper watershed, mobilized public conservation initiatives, promoted green concepts, and enforced penalties against polluters. These measures comprehensively implement the sustainable development philosophy that “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets”. Director H from the Xinhua Township, Huangshan City, revealed during field research that recent institutional innovations include the “Ecological Beauty Supermarket” program. This barter-based system incentivizes farmers’ participation in waste sorting and recycling through material exchanges. The government acts as a pioneer, providing financial support, technical expertise, and institutional frameworks to facilitate public engagement in ecological conservation. Furthermore, the joint “Construction Plan for the Pilot Zone of Eco-Cultural Tourism Cooperation in the Adjacent Hangzhou-Huangshan Area” promotes a tourism development pattern characterized by “strengthening twin towns, lake–city synergy, and scenic corridor linkage”, aiming to establish a world-class “West Lake–Huangshan–Qiandao Lake” golden tourism route.

Government-oriented contracts are effective but create financial difficulties; marketization can overcome this problem very well [

29]. By integrating environmental governance with industrial development, the watershed promotes corporate engagement in emissions trading and carbon sink markets. Market mechanisms stimulate corporate environmental initiatives, attracting substantial private capital to ecological projects while funding green transitions. This strategy enhances environmental quality and accelerates green economic transformation, presenting a “Chinese solution” for global climate response and sustainable development, exemplifying China’s successful balance between ecological governance and industrial progress.

Understanding public perceptions of ecosystem services is crucial for deploying adaptive management strategies [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Governments enhance environmental awareness through education campaigns, empowering communities and social organizations to engage in compensation implementation. Establishing grassroots participation networks ensures public understanding and support, strengthening policy operability and enforcement.

4.2. Public: The Main Force of Ecological Compensation

The public plays a key role in the process of ecological compensation, acting as a driving force. In the case of ecological compensation in the Xin’an River Basin, public participation primarily takes two forms: environmental protection and supervision with feedback. In terms of lifestyle, local residents treat domestic sewage through a comprehensive urban–rural sewage pipeline network that separates rainwater and wastewater. In terms of production practices, a “seven-unification” model for centralized pesticide distribution—covering unified procurement, management, and recycling—has effectively reduced non-point source pollution.

During the authors’ field research in Xiuning District, Huangshan City, it was found that many members of the public exhibited strong environmental awareness. Mr. H, a villager from Wangcun Town, Shexian County, stated that “Why should we protect the environment here? Isn’t it just because we want a cleaner living environment for ourselves? If it were like before, with garbage everywhere and the riverbanks stinking in summer, who could bear it? These past two years the country has started paying attention—look at the roads and riverbanks now, they’re so clean. Life here is more enjoyable too.”.

Mr. C, from Huizhou District, Huangshan City, when talking about participating in ecological governance, said that “As a taxpayer, I have the right to know what the government is doing and how well things are being done. I also hope the voices of the public can be heard by those in power. After all, those projects currently under construction may be temporary concerns for the authorities, but we have to live here long-term.”.

At the same time, the public also supervises the behavior of the government and enterprises and actively provides feedback on the implementation of ecological compensation policies. For instance, a villager in Huangshan City discovered that a local chemical plant was secretly discharging polluted wastewater into a tributary of the Xin’an River at night, leading to fish deaths downstream. He joined with other villagers to report the incident, eventually forcing the plant to shut down for rectification. As one of the participating villagers remarked, “It’s no longer just the government supervising enterprises—our eyes, as ordinary people, are also monitoring devices.”.

4.3. Enterprise: Participant in Ecological Compensation

Enterprises in the Xin’an River watershed ecological compensation framework serve not only as multi-stakeholders but also as market governance participants. While their production activities contribute to regional socio-economic development, they concurrently generate environmental impacts. Corporate engagement manifests in four dimensions: enhancing resource utilization efficiency, reducing pollutant emissions, developing green industries, and participating in ecological restoration projects. Through optimized resource efficiency in production processes, enterprises mitigate overexploitation of natural resources and environmental degradation. For instance, technological innovations in production techniques have enabled certain enterprises to improve energy efficiency while minimizing emissions and waste generation; Mr. Li, R&D Director of YX Enterprise, stated that “We perceive ecological compensation as a transformative opportunity. Confronted with the low competitiveness of traditional high-consumption, high-pollution technologies, our team spent nearly two years achieving breakthroughs in high-performance composite flexible packaging materials. This innovation not only reduced costs and enhanced efficiency, but also secured policy incentives while driving environmental upgrades across the supply chain.”

4.4. Research Institution: Empowerer of Ecological Compensation Technology

Research institutions serve as both technological innovation engines and governance efficiency enhancers in the Xin’an River watershed ecological compensation. Their roles manifest in three dimensions: technological R&D and innovation, ecosystem value accounting for decision-making, and public education. Through technological innovation, research institutions provide solutions for compensation challenges. For instance, low-toxicity pesticide alternatives developed by researchers have reduced pesticide application intensity in Huangshan City by 21.3%, significantly decreasing pollutant influx into the river. Scientific valuation also underpins compensation standard formulation. Collaborative efforts by the Zhejiang Provincial Academy of Ecological and Environmental Sciences, the Zhejiang Ecological Environment Monitoring Center, Zhejiang University, and Zhejiang Gongshang University produced the Technical Guidelines for Agricultural Non-point Source Pollution Investigation and Load Accounting in Zhejiang Province (Trial), standardizing pollution monitoring protocols. Additionally, the Chinese Academy of Environmental Planning quantified the watershed’s ecosystem service value, emphasizing their critical role in water environment compensation mechanisms. Finally, public engagement capacity is enhanced through science outreach. The Qiandao Lake Ecological Monitoring Station regularly publishes water quality reports and disseminates ecological knowledge, strengthening societal monitoring awareness.

4.5. Social Organizations: Promoters of Ecological Compensation

Social organizations assume dual roles as “bridges and facilitators” in the Xin’an River watershed ecological compensation, injecting dynamism and innovation into governance through social mobilization and multi-stakeholder platforms. Their functions encompass three domains: public participation mobilization, institutional optimization promotion, and social oversight reinforcement. Through organizing environmental volunteers for river cleanups and afforestation campaigns, social organizations directly enhance watershed ecology. The “Pure Waters Nurture Xin’an—Protecting the Mother River in Action” initiative employs interactive methods to educate students about watershed characteristics, ancient villages, and conservation narratives. Additionally, establishing the “Hangzhou-Huangshan Joint Expert Committee for Xin’an River-Qiandao Lake Ecological Conservation” has facilitated scientific research and institutional refinement. Finally, independent monitoring systems and public reporting mechanisms improve implementation transparency. The Xinan Village Protection Team conducted over 300 patrol missions (as of October 2024) covering fishing bans, drowning prevention, and ecological tea garden protection, while initiating 10+ special operations for watercourse maintenance and reserve boundary marking. The team member Mr. Sun remarked that “Initially we felt disconnected from river conservation, but now patrols energize us. Lifelong riverside residents clearly perceive environmental improvements, and online visitors’ compliments about our ecosystem fill us with immense pride!”

4.6. Community: Supporters of Ecological Compensation

As direct participants and beneficiaries in the Xin’an River watershed ecological compensation, communities play an indispensable role in reconciling ecological conservation with economic development. Their contributions manifest in pioneering localized compensation models and advancing infrastructure development. Rural communities integrate ecological protection with economic growth through specialized industries like eco-agriculture and eco-tourism. In Shendu Town (She County, Huangshan), the “Spring Water Aquaculture” project has increased farmers’ annual income by 12.7% while reducing chemical fertilizer and pesticide usage by 38%, effectively mitigating agricultural non-point source pollution. Jiukeng Township (Chun’an County, Zhejiang) and Huangtian Township (She County, Anhui) signed the watershed co-governance agreement, collaborating on tea talent cultivation, premium tea variety selection, and cross-regional tourism. Jointly with the County Agriculture Bureau, they formulated the “She County Modern Green Fishery Development Project”, securing funding for prefabricated stinky mandarin fish processing facilities in Tangyue Village, Zhengcun Town. Furthermore, comprehensive sewage pipeline networks enable rainwater–wastewater segregation across urban–rural areas. New rural wastewater treatment terminals achieved 100% standardized operation, with urban treatment rates reaching 98.22% upstream and 97.58% downstream. Municipal solid waste treatment attained full coverage (100%), collectively maintaining the Xin’an River’s Class II water quality standards.

4.7. The Effectiveness of Ecological Compensation Achieved Through Diversified Governance

4.7.1. Ecological Benefit

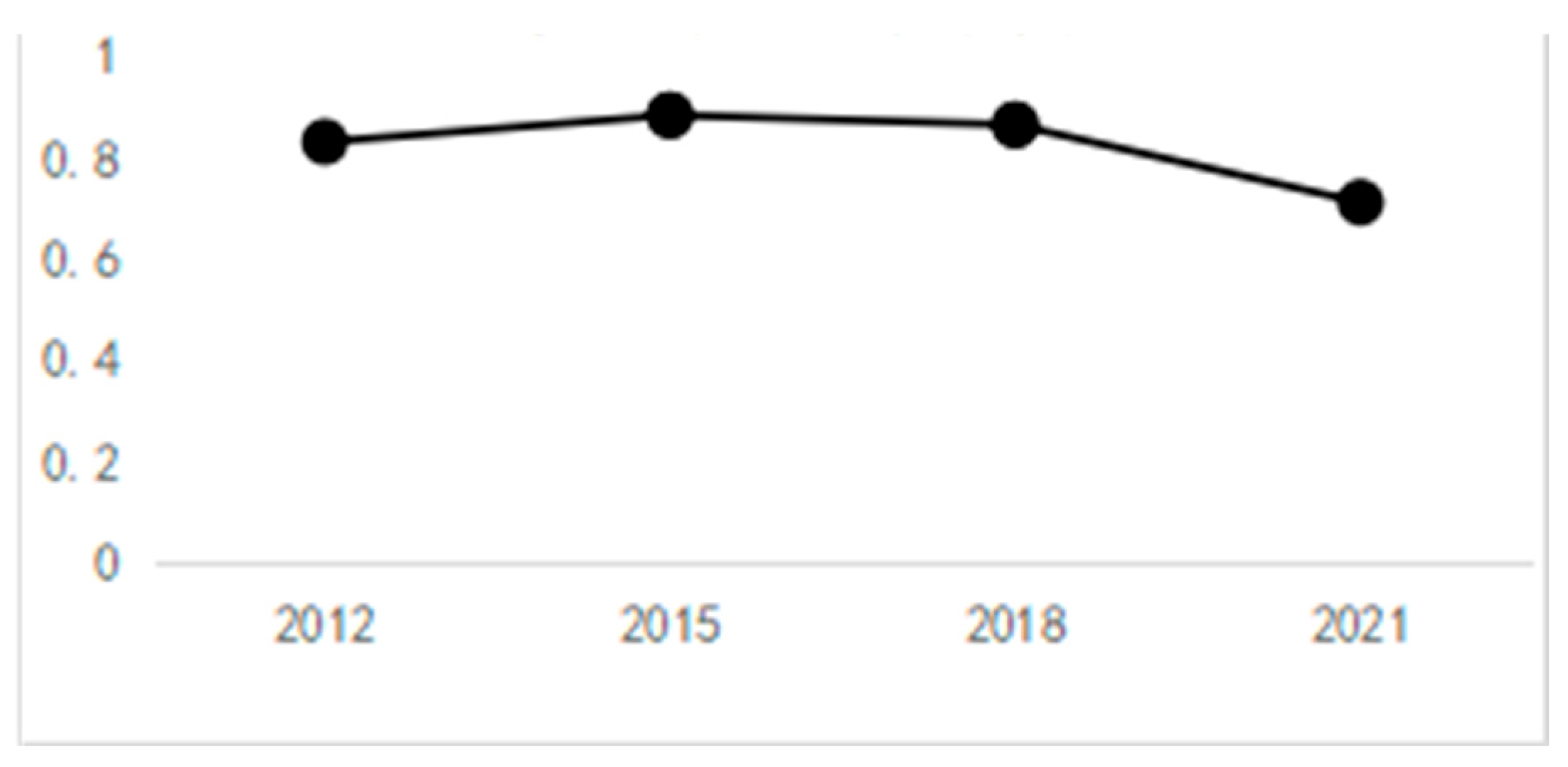

Water quality improvement constitutes a key achievement since the Xin’an River ecological compensation pilot’s initiation. During the 2012–2021 period, the upper watershed maintained excellent water quality, with the P-index consistently meeting compensation agreement targets. Under the first-phase assessment framework, the

p-index decreased from 0.833 (2012) to 0.713 (2021). Analysis of 17-year monitoring data (2005–2021) revealed post-compensation reductions in key parameters: the permanganate index decreased by 28.6%, ammonia nitrogen by 41.2%, and total phosphorus by 33.5%. Qiandao Lake water quality stabilized at Class I, with the trophic state index transitioning to oligotrophic. Huangshan City has achieved marked ecological restoration through watershed compensation implementation. These data were obtained from the official websites of the Huangshan City Government and the Hangzhou City Government. The changes in the

p-value of the Xin’an River water can be seen in

Figure 3.

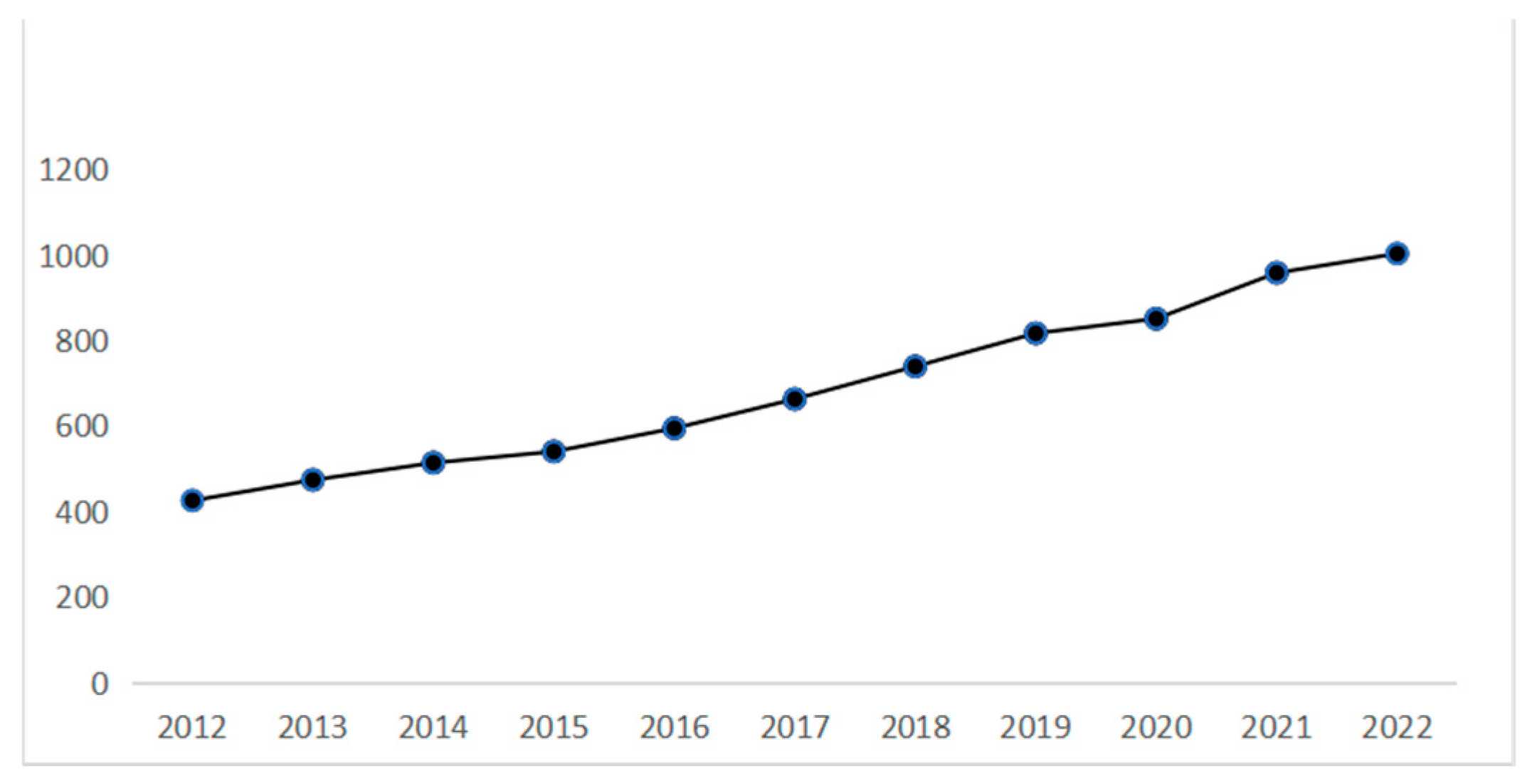

4.7.2. Economic Benefits

As previously analyzed, Huangshan City achieved economic transformation under the incentivizing pressure of the contingent compensation mechanism. Economic gains are evidenced by GDP growth: municipal GDP increased from CNY 42.49 billion (2012) to CNY 100.23 billion (2022), with an average annual growth of CNY 5.774 billion. Notably, this growth persisted despite stricter environmental access controls implemented during the pilot phase. This industrial restructuring facilitates green, circular, and low-carbon development patterns. Economic activities demonstrate dual effects on watershed ecology: while potentially enabling ecological restoration, they also drive upstream economic development through productive engagements. Traditional polluting industries are transitioning towards green high-tech sectors, with green food processing, flexible packaging, specialty chemicals, and automotive electronics emerging as four pillar industries. The integration of tourism, culture, and ecology has positioned tertiary industries as the economic growth engine, effectively converting ecological resources into ecological capital. The GDP changes of Huangshan City from 2012 to 2022 are shown in detail in

Figure 4. These data were obtained from the official websites of the Huangshan City Government and the Hangzhou City Government.

4.7.3. Social Benefit

Huangshan City’s social benefits from watershed ecological compensation manifest through three primary dimensions: first, poverty reduction effects. During early industrialization phases, compensation investments directly alleviate poverty. Post-industrial upgrading, compensation enhances self-sustaining development capacity through technological/policy interventions improving production conditions and educational investment, thereby intensifying and sustaining poverty reduction impacts. The second dimension is social equity enhancement. Horizontal compensation transfers narrow urban–rural income gaps by facilitating agricultural labor mobility and industrial structure advancement. The third dimension is demonstration effects. The Xin’an River horizontal compensation pilot, recognized as one of Chna’s Top Ten Reform Cases, has established replicable institutional innovations including integrated coordination, the River Chief system, Ecological Beauty Supermarkets, centralized agrochemical distribution, and transboundary pollution control mechanisms, collectively forming the “Xin’an River Model”. Following State Council Document (2016) No. 31, which designated pilot zones in the Yangtze/Yellow/Xin’an River basins and other transprovincial watersheds, over 13 provincial regions have initiated similar pilots adapting this model.

6. Conclusions

This study systematically investigates the participation mechanisms of multiple stakeholders—including governments, enterprises, the public, research institutions, social organizations, and communities—in transprovincial watershed ecological compensation, using the Xin’an River as a practical case. The research demonstrates the following: (1) The necessity of multi-stakeholder collaboration stems from the attributes of ecological resources as public goods (commonality and externality), requiring cooperative efforts to achieve shared responsibility and cost–benefit equilibrium. (2) The interactive mechanism among stakeholders manifests as a synergistic framework featuring “government leadership, public-driven initiatives, corporate engagement, research empowerment, social organization facilitation, and community support.”. (3) The Xin’an River practice delivers a universally applicable and operational “China’s Approach” whose core experiences offer significant referential value for addressing similar cross-border environmental governance challenges globally. Building on this study, future research could focus on the following aspects: (1) applying quantitative methods to analyze the differences in stakeholder participation in the Xin’an River Basin and (2) conducting comparative studies between the Xin’an River case and other multi-stakeholder participation cases around the world.