The Antecedents and Consequences of Strategic Renewal in Digital Transformation in the Context of Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

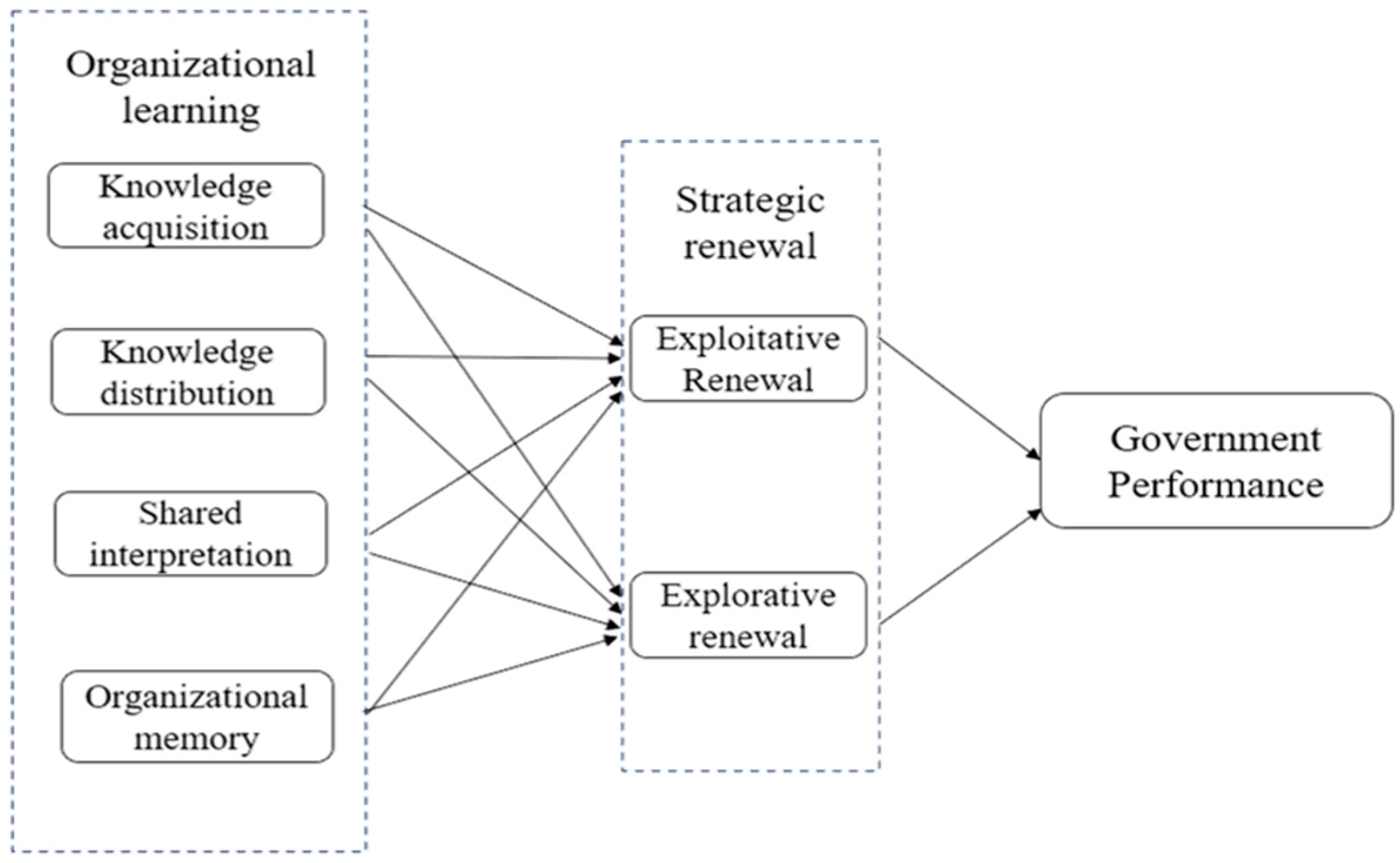

3. Conceptual Model and Hypotheses

3.1. Organizational Learning

3.1.1. Knowledge Acquisition (KA)

3.1.2. Knowledge Distribution (KD)

3.1.3. Shared Interpretation (SI)

3.1.4. Organizational Memory (OM)

3.2. Strategic Renewal

4. Methodology

4.1. Measurement of Variables

4.2. Data Collection

5. Data Analysis and Results

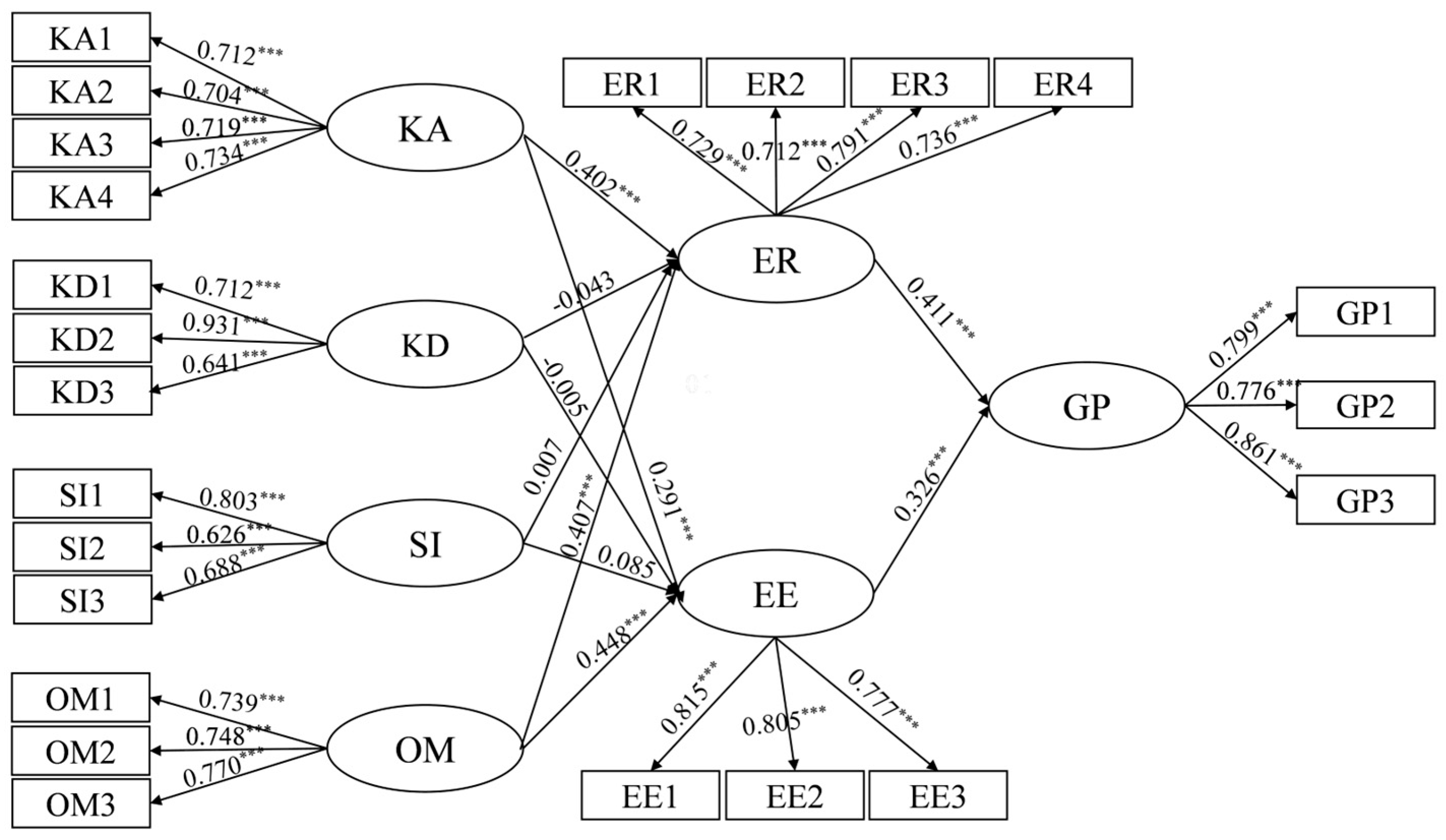

5.1. Scale Validation

5.2. Model Testing Results

5.3. Model-Fit Indices

6. Discussion

7. Implications

7.1. Implications for Theory

7.2. Implications for Practice

8. Limitations and Further Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Camodeca, R.; Almici, A. Digital transformation and convergence toward the 2030 agenda’s sustainability development goals: Evidence from Italian listed firms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asi, Y.M.; Williams, C. The role of digital health in making progress toward Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3 in conflict-affected populations. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2018, 114, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guandalini, I. Sustainability through digital transformation: A systematic literature review for research guidance. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, C.I.; Magnusson, J.; Rost, M. Leave it to the parents: How hacktivism-as-tuning reconfigures public sector digital transformation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2025, 42, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Yang, J.; Shi, X. Towards a comprehensive understanding of digital transformation in government: Analysis of flexibility and enterprise architecture. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittaway, J.J.; Montazemi, A.R. Know-how to lead digital transformation: The case of local governments. Gov. Inf. Q. 2020, 37, 101474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangi, L.; Janssen, M.; Benedetti, M.; Noci, G. Digital government transformation: A structural equation modelling analysis of driving and impeding factors. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 60, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seele, P.; Lock, I. The game-changing potential of digitalization for sustainability: Possibilities, perils, and pathways. Sustain. Sci. 2017, 12, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J.D.; Schmidt-Traub, G.; Mazzucato, M.; Messner, D.; Nakicenovic, N.; Rockström, J. Six transformations to achieve the sustainable development goals. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouvea, R.; Kapelianis, D.; Kassicieh, S. Assessing the nexus of sustainability and information & communications technology. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2018, 130, 39–44. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz, R.; Montalvo, R. Digital transformation as an enabler to become more efficient in sustainability: Evidence from five leading companies in the Mexican market. Sustainability 2022, 14, 15436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsamakas, E. Digital transformation and sustainable business models. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. Digital transformation and sustainable performance: The moderating role of market turbulence. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 104, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosário, A.T.; Dias, J.C. Sustainability and the digital transition: A literature review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Mikalef, P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Jaccheri, L.; Krogstie, J. Responsible digital transformation for a sustainable society. Inf. Syst. Front. 2023, 25, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajishirzi, R.; Costa, C.J.; Aparicio, M. Boosting sustainability through digital transformation’s domains and resilience. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, S.J.; Lee, J. Digital government transformation in turbulent times: Responses, challenges, and future direction. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curtis, S. Digital transformation—The silver bullet to public service improvement? Public Money Manag. 2019, 39, 322–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gritt, E.; Forsgren, E.; Pandza, K. Liminal digital transformation in public sector: The case of UK policing. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2024, 33, 101851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, L.; Desouza, K.C.; Dawson, G.S.; Pardo, T. Digital transformation of the public sector: Designing strategic information systems. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2024, 33, 101853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faro, B.; Abedin, B.; Cetindamar, D. Hybrid organizational forms in public sector’s digital transformation: A technology enactment approach. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2022, 35, 1742–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venson, E.; da Costa Figueiredo, R.M.; Canedo, E.D. Leveraging a startup-based approach for digital transformation in the public sector: A case study of Brazil’s startup gov. br program. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabryelczyk, R. Has COVID-19 accelerated digital transformation? Initial lessons learned for public administrations. Inf. Syst. Manag. 2020, 37, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammer, A.; Gueldenberg, S.; Kraus, S.; O’Dwyer, M. To change or not to change–antecedents and outcomes of strategic renewal in SMEs. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 739–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, Y.; Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O.F.; Xing, Y. HRM algorithms: Moderating the relationship between chaotic markets and strategic renewal. Br. J. Manag. 2025, 36, 529–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, R.; Helfat, C.E. Strategic renewal of organizations. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.H.; Majid, A.; Yasir, M. Strategic renewal of SMEs: The impact of social capital, strategic agility and absorptive capacity. Manag. Decis. 2021, 59, 1877–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Lane, H.W.; White, R.E. An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, D.; Crossan, M. Strategic leadership and organizational learning. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2004, 29, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergel, I.; Edelmann, N.; Haug, N. Defining digital transformation: Results from expert interviews. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 101385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, P. Digital transformation of the Italian public administration: A case study. Commun. Assoc. Inf. Syst. 2020, 46, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begany, G.M.; Gil-Garcia, J.R. Open government data initiatives as agents of digital transformation in the public sector: Exploring the extent of use among early adopters. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, M.G. Reflections on three decades of digital transformation in local governments. Local Gov. Stud. 2024, 50, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Tan, G.W.H.; Cham, T.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Aw, E.C.X.; Currie, W. Government digital transformation: Understanding the role of government social media. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crusoe, J.; Magnusson, J.; Eklund, J. Digital transformation decoupling: The impact of willful ignorance on public sector digital transformation. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manny, L.; Duygan, M.; Fischer, M.; Rieckermann, J. Barriers to the digital transformation of infrastructure sectors. Policy Sci. 2021, 54, 943–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.J.; Chen, Y.C. Digital transformation toward AI-augmented public administration: The perception of government employees and the willingness to use AI in government. Gov. Inf. Q. 2022, 39, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Panagiotopoulos, P. Coping with digital transformation in frontline public services: A study of user adaptation in policing. Gov. Inf. Q. 2024, 41, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser-Plautz, B.; Schmidthuber, L. Digital government transformation as an organizational response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Gov. Inf. Q. 2023, 40, 101815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, S.; Heuberger, M. Digital transformation going local: Implementation, impacts and constraints from a German perspective. Public Money Manag. 2023, 43, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.J. Digital transformation: Opportunities to create new business models. Strategy Leadersh. 2012, 40, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordella, A.; Bonina, C.M. A public value perspective for ICT enabled public sector reforms: A theoretical reflection. Gov. Inf. Q. 2012, 29, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twizeyimana, J.D.; Andersson, A. The public value of E-Government–A literature review. Gov. Inf. Q. 2019, 36, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Gu, M.; Albitar, K. Government in the digital age: Exploring the impact of digital transformation on governmental efficiency. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 208, 123722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karataş-Özkan, M.; Murphy, W.D. Critical theorist, postmodernist and social constructionist paradigms in organizational analysis: A paradigmatic review of organizational learning literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, M.A. Renegotiating spheres of obligation: The role of hierarchy in organizational learning. Adm. Sci. Q. 2018, 63, 570–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiol, C.M.; Lyles, M.A. Organizational learning. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A.C. The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: A group-level perspective. Organ. Sci. 2002, 13, 128–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argote, L.; Miron-Spektor, E. Organizational learning: From experience to knowledge. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1123–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Li, M.; Yang, X.; Xiao, W. Ambidextrous organizational learning and performance: Absorptive capacity in small and medium-sized enterprises. Manag. Decis. 2023, 61, 3610–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, J.C.; Roldán, J.L.; Leal, A. From entrepreneurial orientation and learning orientation to business performance: Analysing the mediating role of organizational learning and the moderating effects of organizational size. Br. J. Manag. 2014, 25, 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragón-Correa, J.A.; García-Morales, V.J.; Cordón-Pozo, E. Leadership and organizational learning’s role on innovation and performance: Lessons from Spain. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, Y.; Lee, J.N.; Heng, C.S.; Park, J. Effect of multi-vendor outsourcing on organizational learning: A social relation perspective. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 396–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, G.P. Organizational learning: The contributing processes and the literatures. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 88–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahler, J. Influences of organizational culture on learning in public agencies. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 1997, 7, 519–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janson, M.; Cecez-Kecmanovic, D.; Zupančič, J. Prospering in a transition economy through information technology-supported organizational learning. Inf. Syst. J. 2007, 17, 3–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, C.W.; Kankanhalli, A.; Ang, C. Investigating organizational learning in eGovernment projects: A multi-theoretic approach. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2008, 17, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossan, M.M.; Berdrow, I. Organizational learning and strategic renewal. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1087–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, O.; Macpherson, A. Inter-organizational learning and strategic renewal in SMEs: Extending the 4I framework. Long Range Plan. 2006, 39, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, S.; Prügl, R. Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, A.; Dhir, S.; Sushil, S. Coopetition, strategy, and business performance in the era of digital transformation using a multi-method approach: Some research implications for strategy and operations management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 270, 109068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Jin, J.; Li, S.; Zhang, Y. Digital transformation of incumbent firms from the perspective of portfolios of innovation. Technol. Soc. 2023, 72, 102149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Jiménez, D.; Sanz-Valle, R. Innovation, organizational learning, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Vijande, M.L.; López-Sánchez, J.Á.; Trespalacios, J.A. How organizational learning affects a firm’s flexibility, competitive strategy, and performance. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1079–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, G.; Karanasios, S.; Breidbach, C.F. Orchestrating the digital transformation of a business ecosystem. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2022, 31, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, K.; Pérez-Nordtvedt, L. Knowledge acquisition efficiency, strategic renewal frequency and firm performance in high velocity environments. J. Knowl. Manag. 2020, 24, 2035–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwee, Z.; Van Den Bosch, F.A.; Volberda, H.W. The influence of top management team’s corporate governance orientation on strategic renewal trajectories: A longitudinal analysis of Royal Dutch Shell plc, 1907–2004. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 48, 984–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volberda, H.W.; Van den Bosch, F.A.; Flier, B.; Gedajlovic, E.R. Following the herd or not?: Patterns of renewal in the Netherlands and the UK. Long Range Plan. 2001, 34, 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Jiménez-Barrionuevo, M.M.; Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. Transformational leadership influence on organizational performance through organizational learning and innovation. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market orientation and the learning organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real, J.C.; Leal, A.; Roldán, J.L. Information technology as a determinant of organizational learning and technological distinctive competencies. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2006, 35, 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegarra-Navarro, J.G.; Jiménez, D.J.; Martínez-Conesa, E.Á. Implementing e-business through organizational learning: An empirical investigation in SMEs. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2007, 27, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dong, X.Y.; Shen, K.N.; Khalifa, M.; Hao, J.X. Strategies, technologies, and organizational learning for developing organizational innovativeness in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2507–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, C.; Miner, A.S. Organizational improvisation and organizational memory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1998, 23, 698–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girod, M.S. La mémoire organisationnelle [Organizational Memory]. Rev. Française Gest. 1995, 105, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, M.; Yu, Y.; Dong, X. Contributive roles of multilevel organizational learning for the evolution of organizational ambidexterity. Inf. Technol. People 2016, 29, 647–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoofian, A.; Rajabzadeh Ghatari, A.; Fakhar Manesh, M.; Palumbo, R. Digging into the drivers of strategic renewal: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2025, 33, 75–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Raisch, S.; Volberda, H.W. Strategic renewal: Past research, theoretical tensions and future challenges. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2018, 20, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievinen, H.M.; Ikäheimonen, T.; Pihkala, T. Strategic renewal in a mature family-owned company—A resource role of the owners. Long Range Plan. 2020, 53, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, A.; Barker, V.L., III; Raisch, S.; Whetten, D. Strategic renewal in times of environmental scarcity. Long Range Plan. 2016, 49, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, D.; Kreutzer, M.; Lechner, C. Resolving the paradox of interdependency and strategic renewal in activity systems. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2015, 40, 210–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortovanyi, L.; Szabo, R.Z.; Fuzes, P. Extension of the strategic renewal journey framework: The changing role of middle management. Technol. Soc. 2021, 65, 101540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.; Peltoniemi, M.; Lamberg, J.A. Strategic renewal: Can it be done profitably? Long Range Plan. 2022, 55, 102179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, S.W.; Lane, P.J. Strategizing throughout the organization: Managing role conflict in strategic renewal. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 154–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, J.O.; Huff, A.S.; Thomas, H. Strategic renewal and the interaction of cumulative stress and inertia. Strateg. Manag. J. 1992, 13 (Suppl. S1), 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantunen, A.; Tuppura, A.; Pätäri, S. Dominant logic–Cognitive and practiced facets and their relationships to strategic renewal and performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2024, 42, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussan, F.; Acs, Z.J. The digital entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Bus. Econ. 2017, 49, 55–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Tian, Z. Environmental uncertainty, resource orchestration and digital transformation: A fuzzy-set QCA approach. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 139, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Xu, Y.; Li, W. A study on the strategic momentum of SMEs’ digital transformation: Evidence from China. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, C. From riches to digitalization: The role of AMC in overcoming challenges of digital transformation in resource-rich regions. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2024, 200, 123153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.P.; Ungson, G.R. Organizational memory. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 57–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, B.; Furst, S.; Blackburn, R. Overcoming barriers to knowledge sharing in virtual teams. Organ. Dyn. 2007, 36, 259–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, R.; Rehman, M.; Wang, K.S.; Hashmani, M.A. Systematic literature review of knowledge sharing barriers and facilitators in global software development organizations using concept maps. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 24231–24247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disterer, G. Individual and social barriers to knowledge transfer. In Proceedings of the 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, 6 January 2001; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

| Measure | Items | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genders | Male | 126 | 40.2% |

| Female | 187 | 59.8% | |

| Age | Less than 25 years old | 95 | 30.2% |

| 25–34 years old | 165 | 52.7% | |

| 35–44 years old | 38 | 12.0% | |

| 45–54 years old | 13 | 4.0% | |

| 55 years old and above | 3 | 1.1% | |

| Education | Junior college | 1 | 0.3% |

| College | 18 | 5.7% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 173 | 55.3% | |

| Master’s degree and above | 121 | 38.7% | |

| Work experience | Less than 3 years | 151 | 48.4% |

| 3–5 years | 105 | 33.6% | |

| 6–10 years | 36 | 11.4% | |

| 10 years and above | 21 | 6.6% |

| Construct | Measure | Load Factor | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge acquisition (KA) | I understand the department’s work philosophy | 0.712 | 0.5146 | 0.8091 |

| I was encouraged to gather information about departmental change | 0.704 | |||

| our department constantly evaluate the need to adapt to the business | 0.719 | |||

| Our department uses a formal procedure to evaluate results and compare them with other departments | 0.734 | |||

| Knowledge distribution (KD) | Our department has established a meeting schedule with other departments to consolidate available information | 0.712 | 0.5949 | 0.811 |

| Our department will spend some time discussing future development needs | 0.931 | |||

| Our department will internally communicate the overall goals of the department | 0.641 | |||

| Shared interpretation (SI) | Our department will promptly update our perspective about the external environment | 0.803 | 0.5033 | 0.7505 |

| Our department will prepare a brief report | 0.626 | |||

| Our department conducts a thorough analysis of the different options to choose the best one | 0.688 | |||

| Organizational memory (OM) | Turnover in our department does not affect the department’s ability to create new knowledge | 0.739 | 0.5662 | 0.7965 |

| Our department knows each member’s specialty and experience | 0.748 | |||

| When our department faces new opportunities or problems, we can promptly contact key personnel | 0.77 | |||

| Exploitative renewal (ER) | Our department improves the efficiency of public services | 0.815 | 0.6387 | 0.8413 |

| Our department increases economies of scale in existing services | 0.805 | |||

| Our department expands its services to existing users | 0.777 | |||

| Explorative renewal (EE) | Our department will be launching new services | 0.736 | 0.5514 | 0.8308 |

| Our department experiment with new services | 0.791 | |||

| Our department will invent new services | 0.712 | |||

| Our department embraces the need to go beyond existing services | 0.729 | |||

| Government performance (GP) | Our department adopts a data-driven model | 0.799 | 0.6606 | 0.8536 |

| Our department can restructure the department by data analysis | 0.776 | |||

| Our department has established a decision-making by data analysis | 0.861 |

| Construct | AVE | Factor Correlation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA | KD | SI | OM | ER | EE | GP | ||

| KA | 0.515 | 0.809 | ||||||

| KD | 0.595 | 0.242 | 0.811 | |||||

| SI | 0.503 | 0.101 | 0.089 | 0.751 | ||||

| OM | 0.566 | 0.484 | 0.141 | 0.082 | 0.797 | |||

| ER | 0.639 | 0.511 | 0.141 | 0.110 | 0.498 | 0.841 | ||

| EE | 0.551 | 0.437 | 0.156 | 0.126 | 0.485 | 0.578 | 0.831 | |

| GP | 0.661 | 0.412 | 0.186 | 0.104 | 0.362 | 0.483 | 0.520 | 0.854 |

| Model-Fit Indices | Results | Recommended Value |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-square statistic χ2/df | 1.477(χ2 = 316.143/ df = 214) | ≤3 |

| GFI | 0.920 | ≥0.9 |

| CFI | 0.966 | ≥0.9 |

| NFI | 0.904 | ≥0.9 |

| RMSEA | 0.039 | <0.1 |

| Hypotheses | Path Coefficients | Result |

|---|---|---|

| KA→ER | 0.291 *** | Supported |

| KA→EE | 0.402 *** | Supported |

| KD→ER | −0.005 | Not support |

| KD→EE | −0.043 | Not support |

| SI→ER | 0.085 | Not support |

| SI→EE | 0.07 | Not support |

| OM→ER | 0.448 *** | Supported |

| OM→EE | 0.407 *** | Supported |

| ER→GP | 0.411 *** | Supported |

| EE→GP | 0.326 *** | Supported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiao, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H. The Antecedents and Consequences of Strategic Renewal in Digital Transformation in the Context of Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157055

Xiao J, Lu Y, Zhang H. The Antecedents and Consequences of Strategic Renewal in Digital Transformation in the Context of Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157055

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiao, Jianying, Yitong Lu, and Hui Zhang. 2025. "The Antecedents and Consequences of Strategic Renewal in Digital Transformation in the Context of Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157055

APA StyleXiao, J., Lu, Y., & Zhang, H. (2025). The Antecedents and Consequences of Strategic Renewal in Digital Transformation in the Context of Sustainability: An Empirical Analysis. Sustainability, 17(15), 7055. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17157055