5.1. Summary of Findings

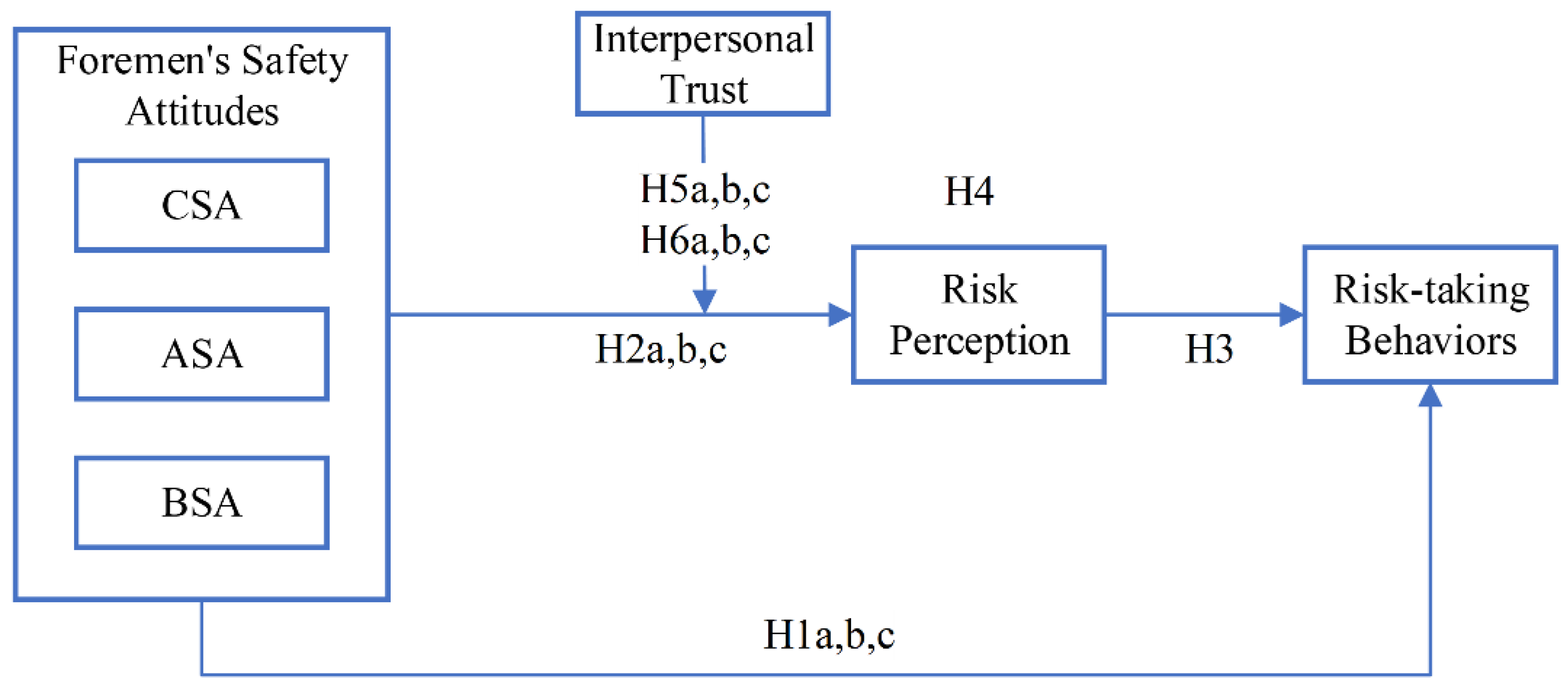

In the context of the construction industry—where OHS management faces particularly significant challenges—mobilizing the proactive role of foremen in OHS management can help the sector address these challenges and accelerate the achievement of SDG 3 and SDG 8. Motivated by this practical need, the study developed a theoretical model positioning foremen’s SAs as the antecedent variable, RP as the mediator, IPT as the moderator, and RTBs as the outcome variable. An empirical investigation was conducted using SEM. The results revealed several key findings.

First, foremen’s SAs were found to be significant negative predictors of workers’ RTBs, with ASA and BSA showing significant negative effects on RTBs at the 0.05 and 0.001 levels, respectively. This finding aligns with existing literature and confirms the critical role of foremen in shaping workers’ safety practices [

20,

38]. However, by integrating Social Learning Theory and Social Information Processing Theory, this study identifies and empirically validates a dual-pathway mechanism through which foremen’s SAs influence workers’ RTBs: foremen’s SAs not only directly affect workers’ behavioral decisions (direct pathway) but also indirectly shape RTBs by influencing workers’ RP through the informational cues conveyed in foremen’s words and actions (indirect pathway). Compared to prior research that primarily emphasizes the direct influence of foremen on workers’ behaviors [

21,

74], this study broadens the theoretical perspective on how foremen generate social influence within crews. It highlights their multifaceted roles in workers’ decision-making processes—as behavioral models, information intermediaries, norm interpreters, and emotional climate setters. These insights provide a novel theoretical perspective on the unique value of foremen in frontline OHS management.

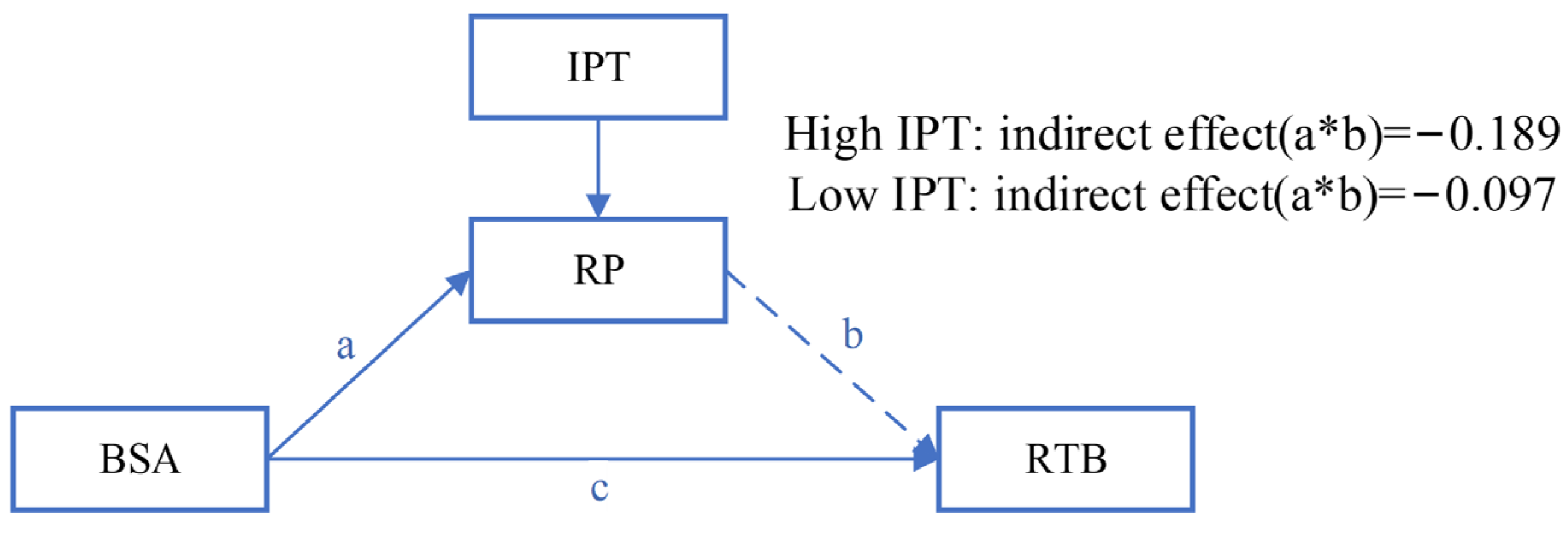

Second, the study reveals the multidimensional complexity of the mechanisms through which foremen’s SAs influence workers’ RTBs, with distinct pathways associated with each of the three attitude dimensions. This finding provides an integrated perspective for comprehensively understanding the multifaceted roles of foremen in on-site safety management. Specifically, BSA exert the strongest impact, consistent with prior research [

20,

74]. BSA shows both a significant direct inhibitory effect on RTBs and an indirect effect via workers’ RP. This supports the theory of “role synergy” [

75], which posits supervisors collaboratively shaping individual behaviors through behavioral modeling, procedural monitoring, and capability transmission. In contrast, CSA influence RTBs only indirectly, indicating workers primarily interpret CSA as social cues for risk assessment rather than direct behavioral commands [

27]. ASA mainly exert a significant direct effect without a significant indirect one, suggesting workers’ decisions are strongly affected by foremen’s immediate emotional states, likely due to emotional contagion in daily interactions [

76,

77]. Emotional influences may also have delayed effects requiring more time to translate into risk assessment cues [

78], which might explain the non-significant indirect effect found here. In summary, this study deconstructs foremen’s influence from a broad and unified concept into three distinct “influence channels”—behavioral, cognitive, and affective—each operating through different mechanisms. The practical implication is that future OHS interventions should move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach and instead develop differentiated strategies tailored to each specific channel.

Third, this study validates the mediating role of RP in the relationship between foremen’s SAs and workers’ RTBs. Specifically, RP significantly mediates the effects of both CSA and BSA on RTBs (

p < 0.01), thereby uncovering the psychological foundation of foremen’s indirect influence. Although the inhibitory effect of RP on RTBs remains contested in some studies [

79], such inconsistency may stem from the following: (i) boundary conditions, where contextual factors moderate the effect of RP [

80], and (ii) variations in RP types, as rational RP may exert limited influence on workers’ safety behaviors [

43]. Nonetheless, the present findings align with the mainstream view that RP significantly reduces risk-taking behavior [

43,

81], and by confirming its mediating role, the study offers a more nuanced understanding of how foremen exert indirect influence. While RP is inherently subjective, its formation is often shaped by workers’ interpretations of their social environment [

82], particularly on construction sites characterized by dynamic, unpredictable, and ambiguous conditions [

33]. Thus, RP is not merely a product of individual cognitive processing but also a psychological response triggered by foremen through social influence mechanisms. It plays a pivotal bridging role in the pathway from foremen’s attitudes to workers’ behaviors. This finding provides a clearer roadmap for understanding the complex social influence processes underlying workplace safety.

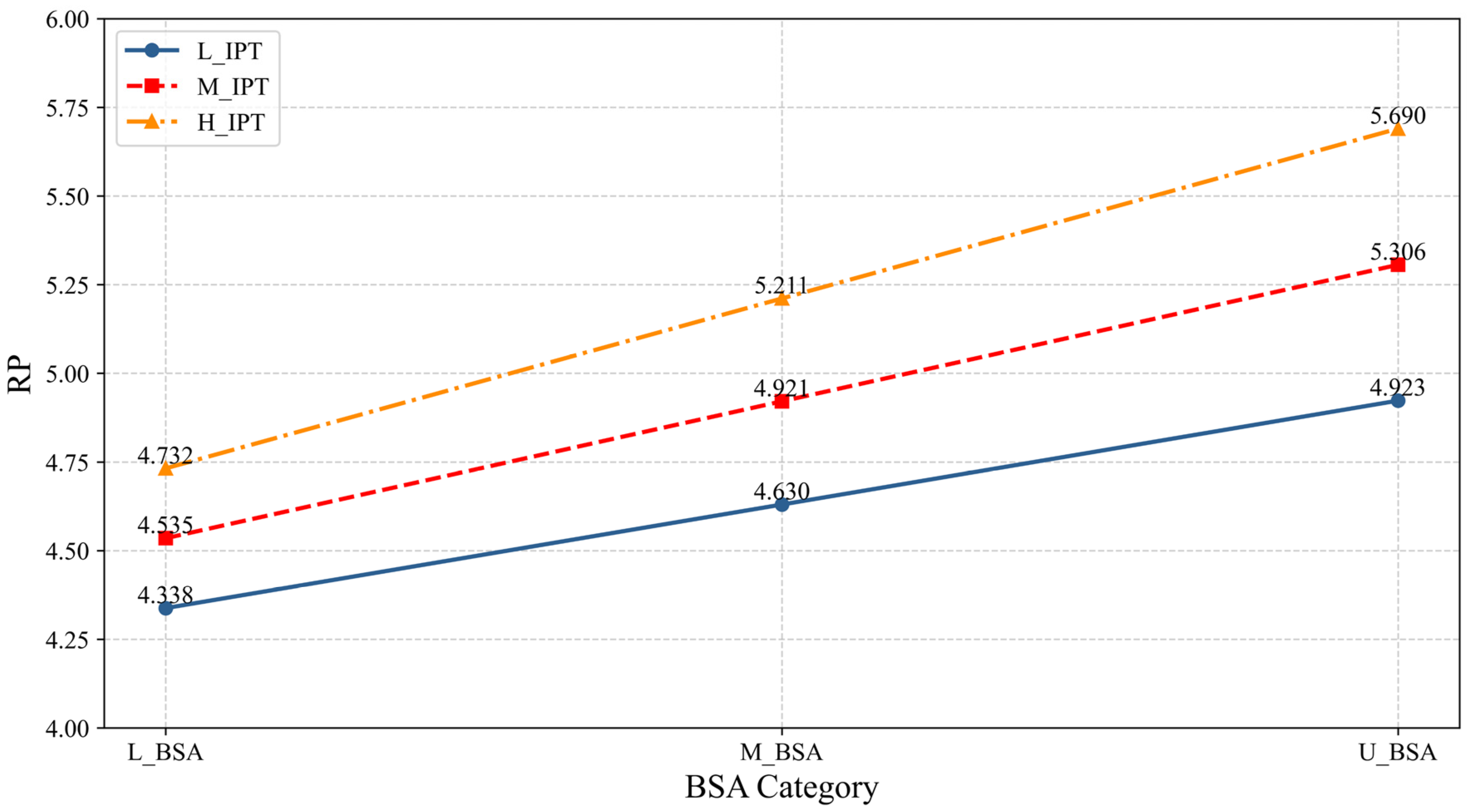

Fourth, the moderating effect of IPT was significant only in the relationship between foremen’s BSA and workers’ RP (the moderating effect of IPT on the BSA–RP link was significant at the

p < 0.001 level), revealing that the influence of foremen extends beyond the domain of interpersonal relationships. Trust fundamentally shapes how individuals perceive and interpret others’ behaviors and intentions [

58]. Consequently, in high-trust environments, workers are more inclined to perceive foremen’s behaviors as normative signals or exemplary role models, thereby exerting stronger influence on their RP. In contrast, CSA primarily reflect foremen’s ideological expressions or attitudinal statements. The impact of such cognitive information depends more on the rigor of the informational arguments and the credibility of the source rather than the relational dynamics between sender and receiver [

83,

84]. This finding conversely highlights the structural power and authority of foremen as “opinion leaders,” whose influence to some extent transcends mere personal likability or trust. Even under low-trust conditions, the cognitive information they convey remains effective. This offers important insights for implementing safety management amid complex interpersonal relationships.

5.2. Theoretical Contribution

This study makes several important theoretical contributions at the intersection of behavioral safety research and sustainable development in the construction industry.

First, this study contributes theoretically by constructing a testable social influence model that links SDGs with frontline OHS practices in the construction sector through a concrete implementation mechanism. Drawing on social cognitive theory and social information processing theory, the model centers on foremen’s SAs, with workers’ RP and IPT serving as key mediating and moderating mechanisms. It offers a conceptual bridge between SDGs (particularly SDG 3 and SDG 8) and frontline RTBs, thereby deepening the understanding of how these global goals can be effectively realized in high-risk work environments.

Second, this study enriches the understanding of foremen’s pivotal role in advancing SDGs—particularly SDG 3 and SDG 8—by deconstructing the dual influence pathways of their SAs. Specifically, it distinguishes and empirically tests the differentiated effects of cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions. The findings reveal that foremen influence workers’ behaviors not only through direct behavioral modeling and emotional climate shaping but also by transmitting social cues via their behavioral tendencies and cognitive expressions. These cues shape workers’ subjective risk assessments. By systematically uncovering how foremen shape RTBs, the study offers theoretical grounding and practical insights for positioning them as active agents in frontline OHS management.

Finally, the moderation analysis results reveal that foremen’s influence arises not only from relational resources but also from their specific role positioning. The presence of multiple parallel influence pathways broadens our understanding of foremen’s function within OHS management. Furthermore, these insights provide a novel theoretical foundation for leveraging foremen to advance SDGs, particularly SDG 5 and SDG 8, at the frontline level.

5.3. Implications for Practice

In the context of high-risk operations, complex workforce compositions, and limited safety resources, effectively leveraging the potential of foremen in OHS management within the construction industry not only complements formal regulations but also serves as a critical pathway for advancing SDGs—particularly SDG 3 and SDG 8. The mechanisms uncovered in this study concerning foremen’s influence on workers’ RTBs lay a theoretical foundation for targeted intervention strategies aimed at empowering foremen and fostering more resilient OHS management systems:

First, enhance the oversight and guidance of foremen’s safety behaviors, transforming them from “passive supervisors” into “proactive role models.” Enterprises should establish a safety behavior feedback loop by conducting regular behavior observations, documentation, and timely feedback to reinforce foremen’s function as safety exemplars. Specifically, in medium-to-large construction firms, digital technologies can be leveraged for continuous behavior monitoring and anomaly detection, thereby creating a sustainable and automated supervision mechanism. For smaller enterprises with limited resources, cost-effective supervision and guidance can be achieved through routine safety inspections combined with basic feedback mechanisms tailored to their operational capacity.

Second, implement targeted training focused on cognitive restructuring. Building on foundational safety knowledge, enterprises should develop scenario-based, visualized training modules—such as accident simulations and case analyses—to help foremen of diverse educational backgrounds deeply understand the accident causation chain and recognize their central role in fostering a psychologically safe environment within their teams, thereby internalizing safety responsibilities. Medium-to-large construction firms can independently design such modules tailored to their operational characteristics, while small enterprises can enhance traditional training by utilizing online resources.

Furthermore, fostering foremen’s emotional identification with safety management through enhanced communication and engagement is essential. To transform foremen from potential psychological resisters into proactive partners, construction firms should establish routine communication mechanisms. Safety managers are encouraged to engage in regular informal dialogues with foremen, listening attentively to their challenges in balancing safety requirements with production schedules. Involving foremen in discussions on improving safety procedures can cultivate a sense of participation and respect, which in turn strengthens their emotional alignment with organizational safety goals. This emotional resonance facilitates the integration of personal commitment with collective safety objectives, ultimately supporting more effective and sustainable safety governance.

Finally, empower workers by enhancing their RP capabilities to establish a bidirectional safety barrier. Beyond top-down influences, enterprises of all sizes should adopt bottom-up approaches to empower workers. Specific measures may include leveraging VR/AR technologies to visualize hazards in high-risk tasks, thereby enhancing the perceptibility of risks. Additionally, during task assignments, providing clear response strategies and necessary supportive resources can help shift workers’ mindsets from passive compliance (“being told to be safe”) to active commitment (“wanting to be safe”). This transformation fosters synergy with foremen’s safety leadership, contributing to the co-construction of a proactive, adaptive safety culture within the organization.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that warrant acknowledgment. First, the reliance on self-reported cross-sectional data inherently restricts causal inferences and temporal dynamics validation. Given that foremen’s influence on workers constitutes a cumulative process, future studies should adopt longitudinal designs with multi-source data triangulation (e.g., behavioral observations coupled with psychometric assessments) to capture evolving interaction patterns.

Second, treating construction workers as a homogeneous group overlooks potential heterogeneity in foremen’s influence. Although individual characteristics of workers may moderate the effects of foremen’s SAs, meaningful subgroup comparisons or multi-group analyses were not feasible due to imbalanced distributions of these variables in the current sample. Future studies should collect more diverse, representative samples to systematically examine these moderating effects.

Third, critical boundary conditions—including pre-existing social ties (kinship/familiarity) between supervisors and workers—are not incorporated into the analytical framework. Subsequent research should systematically examine how these relational dynamics moderate the association between SAs and RTBs.

Finally, the exclusive focus on Chinese construction contexts limits generalizability. Cross-cultural replications across diverse institutional environments are needed to verify the universality of these findings.