Scale and Determinants of Non-Agricultural Business Activity Among Farmers in Poland

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Identifying changes that have occurred since 2002 in the scale and structure of non-agricultural business activity among farmers in Poland;

- Investigating links between agricultural and non-agricultural activities and selected farm characteristics;

- Exploring to what extent the engagement in non-agricultural business activity has been driven by necessity or motivated by market opportunities.

2. Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

- (a)

- To illustrate what changes have occurred in Poland since 2002, in the scale and structure of non-agricultural business activity:

- Number and share of farms with non-agricultural economic activity (in all farms);

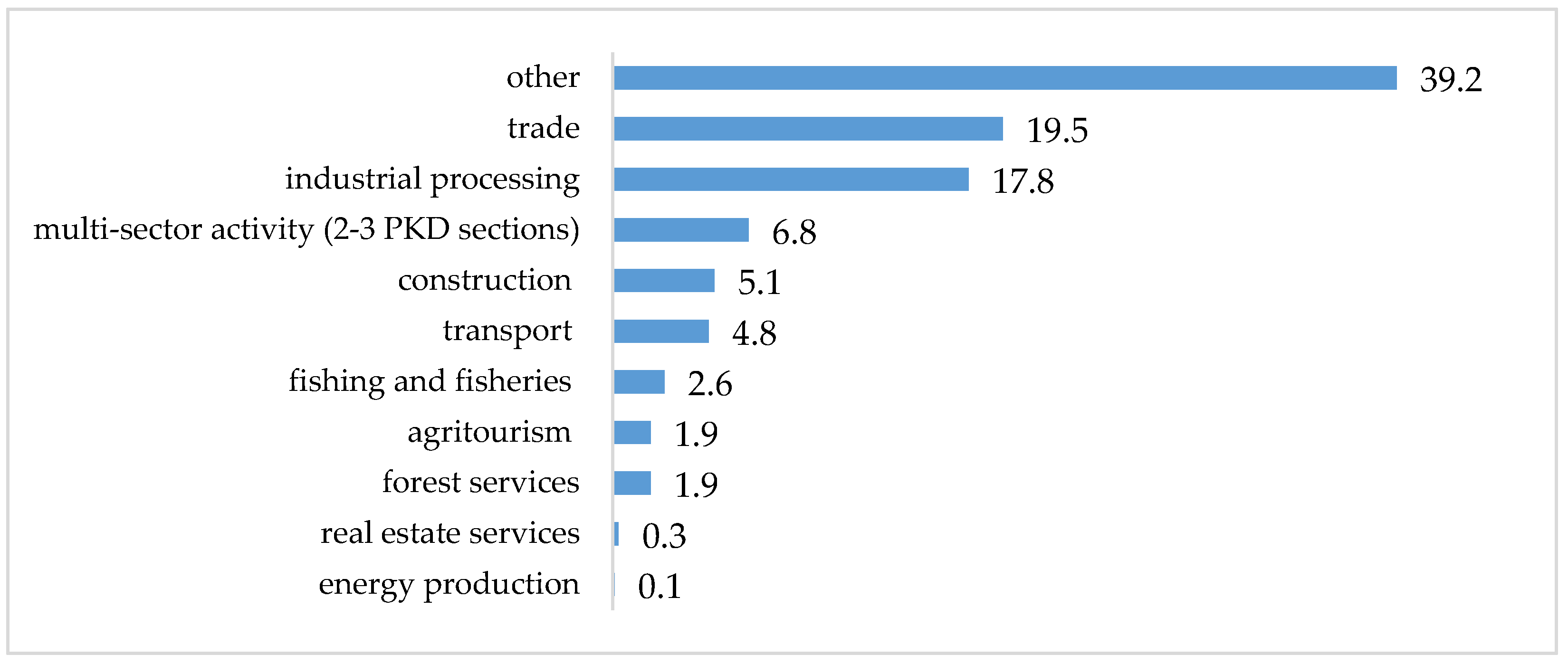

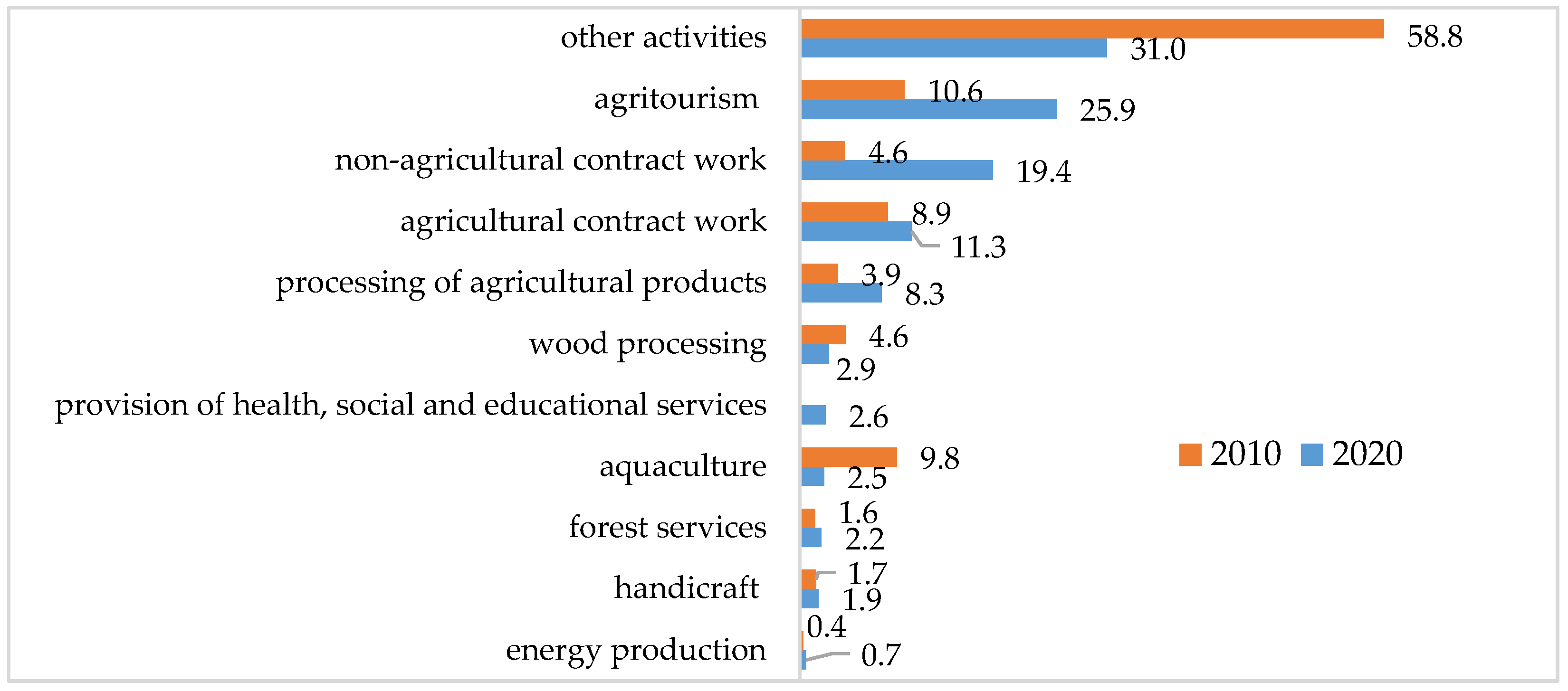

- Structure of farms with non-agricultural economic activity by type of business activity;

- (b)

- To approximate motivations (opportunity vs. necessity entrepreneurship) behind non-agriculture business activity of farmers:

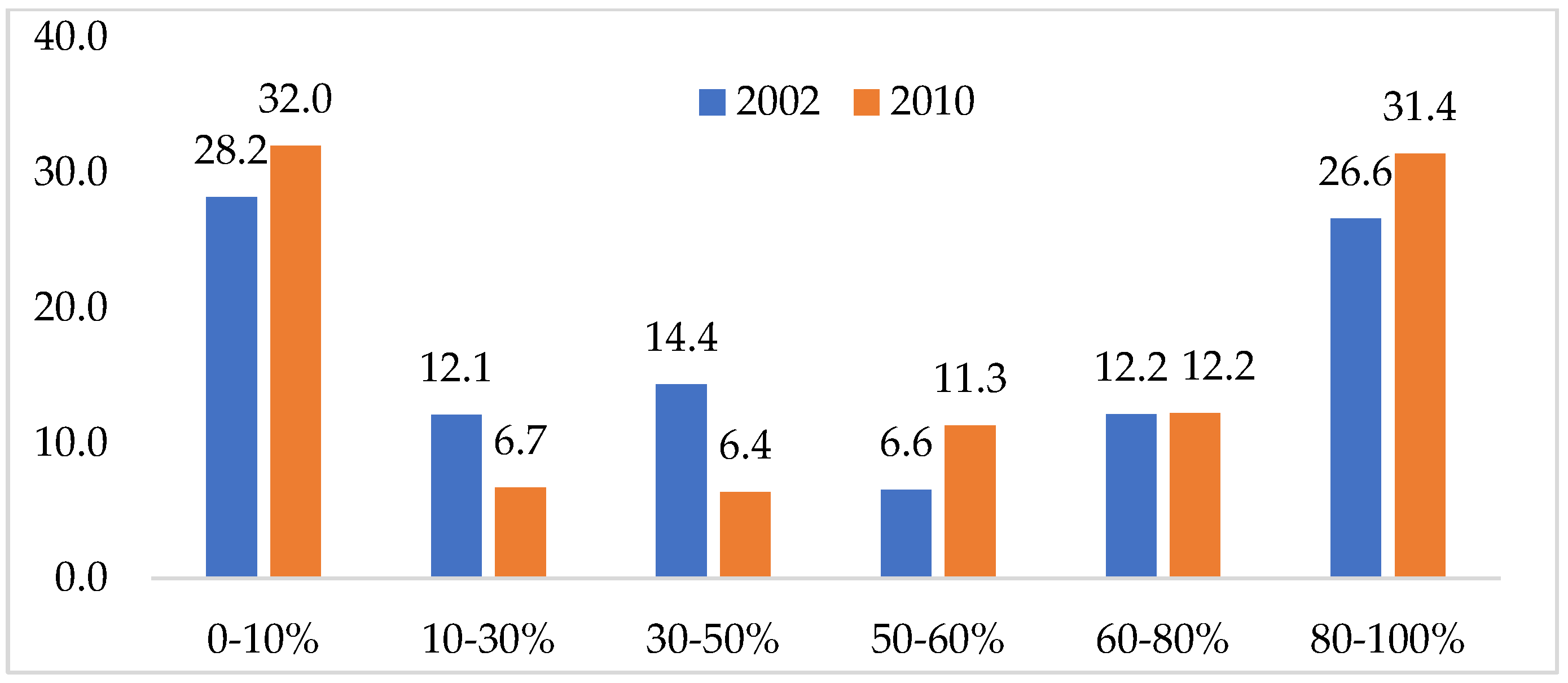

- Share of income from agricultural and non-agricultural activity in total household income;

- Percentage of agricultural holdings whose primary source of livelihood is non-agricultural business activity;

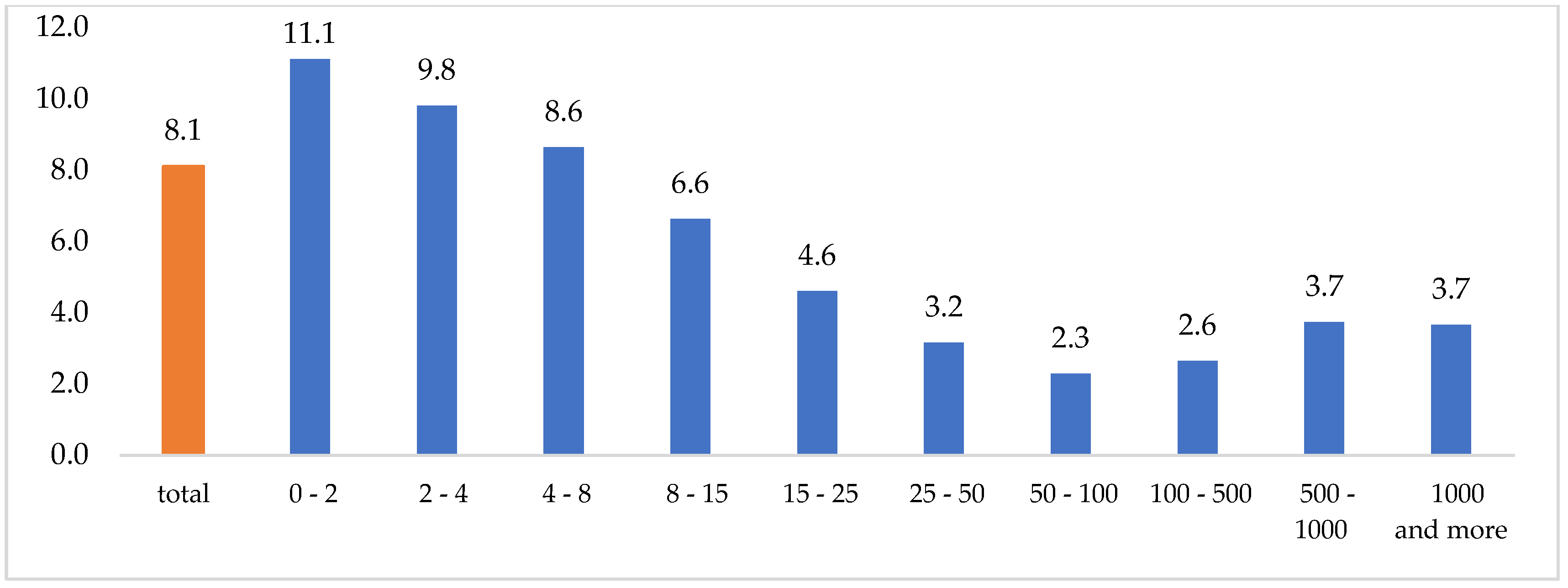

- Selected characteristics of farming households engaged in non-agricultural business activities (e.g., the size of the farm both in economic terms and in terms of the utilized agricultural area, the relationship between the additional business activity and agricultural production).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Scale and Profile of Non-Agricultural Business Activity Among Farmers in Poland

4.2. Exploring the Motivation for Engaging in Non-Agricultural Business Activities

- A limited and decreasing significance of agricultural production as a source of income, as evidenced by the more than a sixfold higher percentage of units producing primarily or exclusively for self-sufficiency;

- On average, about five times smaller economic size of the agricultural holding;

- A lower percentage of farmers managing the holdings who have an agricultural education;

- A very small percentage of holdings involved in animal production, including cattle and pig farming, and consequently, an average livestock density (measured in large animal units) nearly 10 times lower compared with holdings for which agricultural activity was the main source of income;

- Lower agricultural production intensity, as indicated by the level of mineral fertilizer usage per 1 hectare of UAA and the percentage of units applying both mineral and organic fertilization;

- Over 2.5 times lower labor inputs incurred annually for agricultural production.

5. Conclusions

- Over the course of two decades in the 21st century, a relative increase in farmers’ interest in non-agricultural business activities can be observed in Poland, although its scale remains relatively small;

- In the context of the agricultural land area and economic strength of holdings, a tendency toward relatively greater concentration of non-agricultural business activities within small and very small agricultural holdings can be observed in Poland. This would suggest that, in Poland, regressive factors still prevail, pushing farmers to engage in additional business activities. This is usually accompanied by the substitutive (competitive) links between agricultural and non-agricultural business activities, which, in the long term, result in the abandonment of agricultural activities;

- At the same time, the share of farmer-entrepreneurs for whom non-agricultural business activities were the main source of household income steadily increased. Combined with the changing profile of this activity and the increasing interest in this activity among the most economically strong agricultural holdings, this may indicate the gradual spread of pull (opportunity) motivations towards business activities among Polish farmers. It is usually accompanied by the complementary links between agricultural and non-agricultural business activities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fitz-Koch, S.; Nordqvist, M.; Carter, S.; Hunter, E. Entrepreneurship in the agricultural sector: A literature review and future research opportunities. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2018, 42, 129–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Korsgaard, S. Resources and bridging: The role of spatial context in rural entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2017, 30, 224–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsos, A.G.; Ljunggren, E.; Pettersen, T.L. Farm-based entrepreneurs: What triggers the start-up of new business activities? J. Small Bus. Enterp. Dev. 2003, 10, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, A.; Kata, R.; Matuszczak, A. Impact of Budget Expenditures on Structural Changes and Income in Agriculture under the Conditions of CAP Instruments Operated in Poland. Ekonomista 2020, 6, 781–811. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Harkness, C.; Areal, F.J.; Semenov, M.A.; Senapati, N.; Shield, I.F.; Bishop, J. Stability of farm income: The role of agricultural diversity and agri-environment scheme payments. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kisielińska, J. Income from the Farm and Remuneration in EU Countries. Probl. World Agric. 2018, 18, 130–139. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohe, Y. Community-based Rural Tourism and Entrepreneurship. A Microeconomic Approach; Springer: Singapore, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, D. The Importance of Farmers’ Non-Agricultural Economic Activity in the Process of Developing Multifunctionality of Agriculture and Rural Areas; Rzeszów University Press: Rzeszów, Poland, 2014. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Czudec, A. Ekonomiczne Uwarunkowania Rozwoju Wielofunkcyjnego Rolnictwa; Rzeszów University Press: Rzeszów, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kowalczyk, S.; Sobiecki, R. European Model of Agriculture—Determinants of Evolution. Rocz. Nauk. Rol. Ser. G 2011, 98, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ślusarz, G. Entrepreneurship in the multifunctional development of rural areas with diversified natural potential. Ann. PAAAE 2019, XXI, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Yagi, H.; Garrod, G. Determinants of farm diversification: Entrepreneurship, marketing capability and family management. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2019, 32, 607–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajduga, E. Motives for undertaking non-agricultural business activity by farmers. Res. Pap. Wrocław Univ. Econ. 2018, 533, 91–99. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A. Entrepreneurial motivation in start-up and survival of micro- and small enterprises in the rural non-farm economy. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2005, 3, 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmieliński, P.; Pawłowska, A.; Bocian, M. On-farm or off-farm? Diversification processes in the livelihood strategies of farming families in Poland. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2023, 8, 100575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostromęcki, A.; Zając, D.; Mantaj, A. Socio-economic benefits from non-agricultural economic activity conducted by farmers. Zagadnienia Ekon. Rolnej 2015, 2, 40–60. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barczyk-Ciuła, J.; Wojewodzic, T. Relations between Agricultural and Non-Agricultural Activities on Farms Located in the Krakow Metropolitan Area. Ann. PAAAE 2024, XXVI, 11–26. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusz, B.; Kusz, D.; Bąk, I.; Oesterreich, M.; Wicki, L.; Zimon, G. Selected economic determinants of labor profitability in family farms in Poland in relation to economic size. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heffner, K.; Gibas, P.J. Pozarolnicza działalność gospodarcza na obszarach wiejskich. In Wiedza—Przestrzeń—Wieś; Kamińska, W., Janc, K., Legutko-Kobus, P., Eds.; Polska Akademia Nauk: Warszawa, Poland, 2024; pp. 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Sołtysiak, M.; Zając, D. Endogenic conditions for the development of non-agricultural economic activities in rural communities of eastern and western regions of Poland. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. 2023, 175, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naminse, E.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zhu, F. The relation between entrepreneurship and rural poverty alleviation in China. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2593–2611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicka, Z.; Fogel, P. Functional Changes and Conversion of Agricultural Land in the Area with Fragmented Agrarian Structure. Wieś I Rol. 2016, 1, 165–185. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojwodzic, T. Production and Economic Disagrarization of Farms in Poland—Attempt at Measuring the Phenomenon. J. Agribus. Rural. Dev. 2014, 34, 213–223. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Cardillo, C.; Cimino, O. Small Farms in Italy: What Is Their Impact on the Sustainability of Rural Areas? Land 2022, 11, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meuwissen, M.P.M.; Feindt, P.H.; Spiegel, A.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Mathijs, E.; De Mey, Y.; Finger, R.; Balmann, A.; Wauters, E.; Urquhart, J.; et al. A Framework to Assess the Resilience of Farming Systems. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, A.; Stanny, M. Deliberations about the Concept and the Process of Deagrarianisation of the Polish Countryside. Wieś I Rol. 2018, 2, 281–292. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CSO. Systematics and Characteristics of Agricultural Holdings; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. The Characteristics of Agricultural Holdings. Agricultural Census 2010; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. The Agricultural Census 2020. Characteristics of Agricultural Holdings in 2020; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- CSO. Non-Agricultural Activities of Farms; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2004. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- CSO. The Characteristics of Agricultural Holdings in 2016; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Situation of Households in 2003, 2004 and 2005 in the Light of the Results of Household Budget Surveys. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/warunki-zycia/dochody-wydatki-i-warunki-zycia-ludnosci/budzety-gospodarstw-domowych-w-2022-roku,9,21.html (accessed on 11 April 2024). (In Polish)

- CSO. Household Budget Survey 2006-2023; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- The Act of 2 July 2004, The Freedom of Economic Activity (Ustawa z Dnia 2 Lipca 2004 r. o Swobodzie Działalności Gospodarczej (Dz.U. 2004 nr 173 poz. 1807). Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=wdu20041731807 (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- CSO. National Agricultural Census 2020. Research Methodology and Organization; CSO: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Danso-Abbeam, G.; Dagunga, G.; Ehiakpor, D.S. Rural non-farm income diversification: Implications on smallholder farmers’ welfare and agricultural technology adoption in Ghana. Heliyon 2020, 6, e05393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żmija, K. Determinants and prospects of conducting agricultural activities in small farms with non-agricultural activities. Probl. World Agric. 2018, 18, 342–352. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, E.; Vivarelli, M. Entrepreneurship and the Process of Firms’ Entry, Survival and Growth; IZA Discussion Papers, No. 2475; Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA): Bonn, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwan, P.; Thurik, R.; Verheul, I.; Hessels, J. Factors influencing the entrepreneurial engagement of opportunity and necessity entrepreneurs. Eurasian Bus. Rev. 2016, 6, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.D.; Camp, S.M.; Bygrave, W.D.; Autio, E.; Hay, M. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor: 2001 Executive Report; Babson College: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2002; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273705165_Global_Entrepreneurship_Monitor_2001_Executive_Report (accessed on 1 June 2025).

- Fairlie, R.W.; Fossen, F.M. Defining opportunity versus necessity entrepreneurship: Two components of business creation. In Change at Home, in the Labor Market, and on the Job; Polachek, S.W., Tatsiramos, K., Eds.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2020; pp. 253–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brünjes, J.; Revilla Diez, J. Opportunity Entrepreneurs—Potential Drivers of Non-Farm Growth in Rural Vietnam? Working Papers on Innovation and Space, No. 01.12; Philipps-University Marburg, Department of Geography: Marburg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sohns, F.; Revilla Diez, J. Explaining micro entrepreneurship in rural Vietnam—A multilevel analysis. Small Bus. Econ. 2018, 50, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Rodrigues, R.G.; Ferreira, J.J. Agricultural entrepreneurship: Going back to the basics. J. Rural. Stud. 2019, 70, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graskemper, V.; Yu, X.; Feil, J.-H. Analyzing strategic entrepreneurial choices in agriculture—Empirical evidence from Germany. Agribusiness 2021, 37, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antón, J.; Cattaneo, A.; Kimura, S.; Lankoski, J. Agricultural risk management policies under climate uncertainty. Glob. Environ. Change 2013, 23, 1726–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliwoda, M.; Kulawik, J.; Góral, J. Stabilizacja dochodów rolniczych. Perspektywa międzynarodowa, Unii Europejskiej i Polski. Wieś I Rol. 2016, 3, 41–68. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.; Berdegue’, J.; Barrett, C.B.; Stamoulis, K. Household income diversification into rural nonfarm activities. In Transforming the Rural Nonfarm Economy; Haggblade, S., Hazell, P.B.R., Reardon, T., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 115–140. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, A.; Sandretto, C. Stability of Farm Income and the Role of Nonfarm Income in U.S. Agriculture. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 24, 208–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kata, R.; Wosiek, M. Income Variability of Agricultural Households in Poland: A Descriptive Study. Agriculture 2024, 14, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quendler, E.; Morkunas, M. The Economic Resilience of the Austrian Agriculture since the EU Accession. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smędzik-Ambroży, K.; Matuszczak, A.; Kata, R.; Kułyk, P. The Relationship of Agricultural and Non-Agricultural Income and Its Variability in Regard to Farms in the European Union Countries. Agriculture 2021, 11, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kata, R.; Wosiek, M.; Brelik, A. Non-agricultural business activity as a source of income of farmers’ households in Poland. Sci. Pap. Silesian Univ. Technol. Organ. Manag. Series. 2024, 204, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckman, J.; Schimmelpfennig, D. Determinants of farm income. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2015, 3, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzocchi, C.; Guido, S.; Corsi, S. Land use conversion in metropolitan areas and the permanence of agriculture: Sensitivity Index of Agricultural Land (SIAL), a tool for territorial analysis. Land Use Policy 2013, 35, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zborowski, A.; Pawlak, H.; Gałka, J. Social relations between local residents of villages and migrants from the city in the suburban zone of Krakow—A space of conflict or cooperation? Konwersatorium Wiedzy O Mieście 2019, 4, 51–63. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konon, A.; Fritsch, M.; Kritikos, A.S. Business cycles and start-ups across industries: An empirical analysis of German regions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2018, 33, 742–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carree, M.; Dejardin, M. Firm entry and exit in local markets: ‘market pull’ or ’unemployment push’ effects, or both? Int. Rev. Entrep. 2020, 18, 371–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wosiek, M.; Czudec, A.; Kata, R. Relationship between unemployment and new business registrations at the local level: The case of Poland. Post-Communist Econ. 2022, 34, 1083–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazell, P.B.R.; Haggblade, S.; Reardon, T. Structural transformation of the rural nonfarm economy. In Transforming the Rural Nonfarm Economy; Haggblade, S., Hazell, P.B.R., Reardon, T., Eds.; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2007; pp. 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rymuza, K.; Bombik, A.; Kacprzak, T. Entrepreneurship of Farmers in Siedlce County. Probl. Agric. Econ. 2024, 380, 90–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-Viñas, C. Reconversion of Agri-Food Production Systems and Deagrarianization in Spain: The Case of Cantabria. Land 2023, 12, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owoo, N.S.; Naudé, W. Spatial Proximity and Firm Performance: Evidence from Non-Farm Rural Enterprises in Ethiopia and Nigeria. Reg. Stud. 2016, 51, 688–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, M.; Kritikos, A.S. “I want to, but I also need to”: Start-ups resulting from opportunity and necessity. In From Industrial Organization to Entrepreneurship: A Tribute to David B. Audretsch; Lehmann, E.E., Keilbach, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 247–265. [Google Scholar]

- Brünjes, J.; Diez, J.R. ‘Recession push’ and ‘prosperity pull’ entrepreneurship in a rural developing context. Entrep. Reg. Dev. Int. J. 2013, 25, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J. Rural non-farm livelihoods in transition economies: Emerging issues and policies. Electron. J. Agric. Dev. Econ. 2006, 3, 180–224. [Google Scholar]

- Rigg, J. Land, Farming, Livelihoods, and poverty: Rethinking the links in the rural south. World Dev. 2006, 34, 180–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebink, P. De-/re-agrarianisation: Global perspectives. J. Rural Stud. 2018, 61, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czudec, A.; Zając, D. Non-farming entrepreneurship in the farm activity diversification process. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2017, 1, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyżewski, A.; Kata, R.; Matuszczak, M. Impact of national and EU budget expenditures on allocation of production factors in Polish agriculture. Ekonomista 2019, 1, 45–72. (In Polish) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.; Reardon, T.; Webb, P. Non-Farm Income Diversification and Household Livelihood Strategies in Rural Africa: Concepts, Issues and Policy Implications. Food Policy 2001, 26, 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xin, L.; Wang, Y. How farmers’ non-agricultural employment affects rural land circulation in China? J. Geogr. Sci. 2020, 30, 378–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaumik, S.; Dimova, R.; Nugent, J. Off-Farm Labor Supply and Labor Markets in Rapidly Changing Circumstances: Bulgaria during Transition. Econ. Syst. 2011, 35, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Błąd, M. Pluriactivity in agricultural families in Poland. Status quo and trends of changes in 2005-2010. Zagadnienia Ekonomiki Rolnej 2013, 2, 71–84. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Heffner, K. Pozarolnicza działalność gospodarcza na obszarach wiejskich. In Ciągłość i Zmiana. Sto Lat Rozwoju Polskiej Wsi; Halamska, M., Stanny, M., Wilkin, J., Eds.; IRWIR-PAN: Warszawa, Poland, 2019; pp. 947–976. [Google Scholar]

- Di Falco, S.; De Giorgi, G. Farmers to entrepreneurs. In Proceedings of the Selected Paper Prepared for Presentation at the 2019 Agricultural & Applied Economics Association Annual Meeting, Atlanta, GA, USA, 21–23 July 2019. [Google Scholar]

| AC Year: | Percentage of Farms by Main Source of Income: | % of Households with Non-Agricultural Business Activity as the Main Source of Income | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Farming | Employment | Non-Agricultural Business | Pensions and Annuities | Non- Earning Sources | Other Farms * | ||

| 2002 | 27.9 | 24.9 | 5.8 | 28.9 | 3.0 | 9.5 | 49.2 |

| 2010 | 33.8 | 28.8 | 9.4 | 15.3 | 2.7 | 10.0 | 47.7 |

| 2020 | 30.3 | 33.1 | 8.1 | 15.5 | 2.0 | 11.0 | 55.7 |

| Specification | Farms with Main Income from | |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural | Non-Agricultural | |

| Percentage of farms with agricultural production mainly or exclusively for self-supply | 5.8 | 37.6 |

| Average economic size of a farm (in thousands of euros) | 45.7 | 9.3 |

| Percentage of household managers under 40 years of age | 26.5 | 21.0 |

| Agricultural holdings where the manager has an agricultural education | 55.6 | 30.7 |

| in this: | ||

| university education | 4.7 | 4.2 |

| post-secondary | 0.8 | 0.5 |

| vocational secondary | 19.8 | 10.0 |

| basic vocational | 15.8 | 5.4 |

| agricultural course | 14.5 | 10.7 |

| Number of livestock per 1 agricultural holding in livestock units (LSUs) | 19.6 | 2.0 |

| Agricultural holdings keeping: | ||

| Cattle | 42.6 | 6.4 |

| including cows | 32.6 | 4.0 |

| Pigs | 13.3 | 1.8 |

| Agricultural holdings using mineral or lime fertilizers | 85.8 | 59.9 |

| Agricultural holdings using manure | 59.7 | 28.6 |

| Consumption of NPK * per 1 hectare of agricultural land in good agricultural condition | 149.3 | 90.3 |

| Average number of people employed full time in agricultural production | 1.73 | 0.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kata, R.; Wosiek, M.; Brelik, A. Scale and Determinants of Non-Agricultural Business Activity Among Farmers in Poland. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156956

Kata R, Wosiek M, Brelik A. Scale and Determinants of Non-Agricultural Business Activity Among Farmers in Poland. Sustainability. 2025; 17(15):6956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156956

Chicago/Turabian StyleKata, Ryszard, Małgorzata Wosiek, and Agnieszka Brelik. 2025. "Scale and Determinants of Non-Agricultural Business Activity Among Farmers in Poland" Sustainability 17, no. 15: 6956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156956

APA StyleKata, R., Wosiek, M., & Brelik, A. (2025). Scale and Determinants of Non-Agricultural Business Activity Among Farmers in Poland. Sustainability, 17(15), 6956. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17156956