Abstract

Despite the importance of financial literacy, particularly in sustaining and improving rural agriculture, it is documented in the literature that little is known about financial literacy, particularly in rural communities in developing countries. Responding to the calls for research to address this gap, the current study investigates how financial literacy relates to access to funding, innovative service adoption, and sustainable food production among agricultural food producers in Nigeria’s rural communities. A probability sampling technique was used to draw 460 samples from registered rural farmers in the Central Bank of Nigeria’s Anchored Borrower’s Programme for food production in Edo State, Nigeria. Quantitative data were collected using a structured questionnaire. The hypotheses were tested using regression analysis, while descriptive statistics were deployed to analyse the demographic data of the respondents. The outcomes suggest that financial literacy has significant links with access to funding, innovative service adoption and sustainable food production among agricultural food producers in Nigerian rural communities. Based on the outcomes, it is concluded that financial literacy significantly influences sustainable food production in Nigerian rural communities. As such, there is a need for the Nigerian government and financial authorities to embark on a financial literacy drive to increase financial literacy, particularly in light of ever-evolving disruptive financial technologies.

1. Introduction

Financial literacy is an important requirement for sustainable development, as described in the 2030 Agenda set by the United Nations in 2015 [1,2]. It is observed that for sustainably improved agricultural food production, financial management skills are needed [3,4]. Financial literacy refers to an individual’s ability to understand “economic information” and the use of such information to make fruitful financial decisions regarding financial planning, savings, investments, wealth creation, and debt management [5]. This suggests that possessing adequate financial literacy can help rural farmers to make informed decisions, resulting in higher participation in formal financial systems such as the adoption of the mobile banking model [1,2]. Regarding accessibility to agricultural funding, studies have pointed out that understanding access to funding and the factors that influence the adoption of innovative financial services such as payment methods among groups of people is important for the economy [6]. Such financial knowledge can guide the government and financial authorities in formulating policy that can stimulate economic activities, particularly in rural areas [7,8].

But, despite the important place of financial literacy, particularly in sustaining and improving rural farming, current studies have observed that little is known about financial literacy in the literature, particularly in rural communities in developing countries [9,10]. Relying on the work of Goyal and Kumar [11], a study noted that “the consistent deficiency found in scholarly work in the area of financial literacy from developed to developing countries is an issue with huge implications for economic health” [12] (p. 2). More recent research also pointed out that there is a paucity of studies on financial literacy in Nigeria among researchers [2]. It is argued that the complexity and dynamic nature of formal financial products and services [9,10] necessitate continuous research on financial literacy among rural dwellers [3,6,7,13]. The prevailing absence of knowledge about the financial literacy level in developing African countries inhibits the effective and efficient formulation and implementation of financial policies and programmes [14,15].

To address these gaps, this study deployed financial literacy theory to provide insights into how financial literacy influences sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption in Nigerian rural farming communities. With this, the outcomes of the current study possess theoretical implications for research and policy implications for agricultural and financial authorities. First, the study confirms financial literacy theory in the Nigerian context, indicating that the proposition holds true among Nigerian rural farmers. Second, this study responds to calls in the literature for financial literacy studies, particularly in developing nations [9,13,15]. Policy-wise, the outcomes will help Nigerian financial authorities to understand how financial literacy impacts sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption in Nigerian rural farming communities and thereby focus more attention on improving them.

The remaining parts of this paper are arranged in the following order: The literature review comes next, where the theoretical framework and hypothesis development discussions are presented. Next to this part is the Research Methodology Section, which entails discussions of the study’s population, sampling techniques, and the measures. Coming after this section is the Data Analysis and Results Section. Finally, the concluding sections are presented, which include a discussion of the findings, the theoretical and practical implications of the findings, the limitations of the study, and a conclusion.

2. Theoretical Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Operational Definition Construction

Financial literacy: This is viewed as an individual’s ability to understand “economic information” and the use of such information to make fruitful financial decisions regarding financial planning, savings, investments, wealth creation, and debt management [5].

Sustainable food production: This refers to farming and food production practices that result in adequate food outputs that meet the needs of people in the long term without hampering the ability of future generations to meet their food needs [2,3,16].

Access to funding: Specifically, access to funding refers to the ease with which persons, business entities, or organisations secure financial resources for investment purposes. These financial resources include loans, grants, investments, or other forms of financial support [8,15].

Innovative financial service adoption: This is conceptualised as the use of new or greatly enhanced financial technologies, products, and services by individuals, business entities, and institutions [1,17].

2.2. Financial Literacy Theory

In a study of the economic importance of financial literacy, it is argued that financial literacy is a conventional microeconomic proposition regarding saving and consumption decisions that is used to underpin the link between financial literacy and its outcomes [18]. This microeconomic framework proposes that well-informed rational individuals will make profitable financial decisions [7,18]. It is reported that individuals will deliberately invest in the acquisition of financial knowledge to be able to identify and invest in more secure and profitable assets [19]. Based on the theory’s assumption that we argue that well-informed rational individuals will make profitable financial decisions, rural farmers with adequate financial literacy levels will adopt innovative financial services, have access to funding, and engage in sustainable food production in rural Nigerian farming communities.

This conventional microeconomic proposition has underpinned many previous studies. For example, Jappelli and Padula [20] argue that there is a significant relationship between financial literacy and wealth creation. Lusardi et al. [21] reported that making financial knowledge available even to “the least educated group” will increase the groups’ well-being by 82 per cent of their initial wealth. Bernheim [22] reported that households in the United States of America that lack basic knowledge of financial matters make uninformed financial decisions in their saving patterns. Agarwal et al. [23] found that financial ‘mistakes’ are predominant among people with the lowest financial knowledge. Also, Song [24] discovered in China that contributions to pension savings substantially increased among farmers when they gained knowledge of compound interest.

2.3. Linking Financial Literacy to Sustainable Food Production in Nigerian Rural Farming Communities

The ultimate aim of investments in farm activities is to attain sustainable optimum productivity [4,15]. The outcomes of empirical research suggest that access to credit, good investment decisions, and sustainable higher performance are achieved through adequate financial management knowledge [8,15]. Koomson et al. [25] argue that individuals with adequate financial knowledge often have access to formal financial products and services that enable them to increase performance. Gaudecker [26] explored the impacts of financial literacy on individuals’ decision-making regarding portfolio diversification using OLS regression and found that people who follow financial experts’ advice make better investment decisions than those who lack such assistance.

It is documented in the literature that the availability of viable financial products and services, such as savings and borrowing opportunities, to farmers who are desirous of expanding their farm business will enable such farmers to acquire modern farm inputs to improve productivity [27]. Examining how farmer education impacts farm productivity in evolving modern technologies, a study found that education significantly increases the productivity of farmers by way of adopting modern technology [28]. Lusardi and Mitchell [29] pointed out that poor business performance and the bad investment habit of clinging to less risky but low-profit-yielding investments are often attributable to low financial literacy. Investigating how financial literacy affects household income among 572 households in rural Ghana, it was reported that financial literacy significantly impacts household income [6]. The study concludes as follows: “We argued that financial literacy is essential to access and optimally use available financial services” [6] (p. 2). Studies also found that financial literacy equips people to make profitable investment decisions [30,31]. Lusardi and Tufano [32] predicted that people with low financial literacy suffer the high costs of financial transactions, such as higher transaction fees and high-cost borrowing. Flowing from the foregoing literature, we argue that farmers in rural Nigerian farming communities who possess adequate financial literacy levels will be able to engage in sustainable food production. For example, it is suggested that financial literacy equips individuals to make profitable investment decisions [30,31] and significantly increases the productivity of farmers [28]. To test this assumption, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1.

A significant positive relationship exists between financial literacy and sustainable food production in Nigerian rural farming communities.

2.4. Linking Financial Literacy to Access to Agricultural Funding in Nigerian Rural Farming Communities

The ability of people to have adequate access to credit is suggested to be a function of financial literacy. For example, it is reported that increased financial literacy would result in increased savings and access to credit, particularly in low-income societies [31]. It is argued that microcredit received by Ghanaian rural households lacks significant impacts on their earnings due to poor financial mismanagement skills resulting in inappropriate borrowing and investment decisions [27]. The low access to formal credit is attributed to a lack of financial and banking education, among other things [33]. A study reported a significant positive link between financial literacy and access to formal credit facilities among business owners in China [34]. Twumasi et al. [8] argue in their study of how financial literacy impacts household income that financial literacy is essential to access and optimally use available financial services. The study further argues the following: “Financial literacy has a direct effect on access to financial services” [6] (p. 2). Using multiple regressions and logistic analysis to test the impacts of financial literacy on access to microcredit among farmers in Indonesia, it was found that there is a significant link between financial literacy and microcredit accessibility [35]. In line with the arguments in the literature, we argue that financial literacy will significantly predict access to funding in Nigerian rural farming communities and therefore propose the following:

H2.

A significant positive relationship exists between financial literacy and access to funding in Nigerian rural farming communities.

2.5. Linking Financial Literacy to the Adoption of Innovative Financial Services in Nigerian Rural Farming Communities

It is argued that since knowledge is an important factor in comprehending financial technological solutions, it is crucial to understand how financial literacy influences the adoption of innovative financial services [2,6,7], such as the choice of payment model among consumers [1,17]. Assessing the methods of payments in Canada, Henry et al. [36] reported that individuals who are more financially literate hold less cash and adopt more cashless methods of payment. A study has shown how financial knowledge affects credit card use. For example, studying the link between financial knowledge and the use of credit cards among college students, Robb [37] found that students that possess higher financial knowledge make reasonable use of credit cards. Kim et al. [38] demonstrated that financial knowledge significantly predicts monthly credit card repayments and other timely payments. Studies have empirically demonstrated that knowledge of financial products and services significantly predicts payment choices among consumers in Poland [1,17]. Yuwono [39] reported that knowledge of financial institutions significantly relates to the choice of financial products among farmers.

Imhanrenialena et al. [7] observed in an empirical study involving marketers of bank financial services in rural areas in Nigeria that some of the rural farmers that possess considerable levels of financial literacy easily adopt modern financial transactions. It was reported by the Indonesian Financial Services Authority [40] that low knowledge and comprehension of financial products and services lead to the low utilisation of financial products and services among Indonesian people. Based on the foregoing discussion in the literature, we assume that financial literacy has a significant relationship with the adoption of innovative financial services in rural Nigerian farming communities. We therefore hypothesise the following:

H3.

A significant positive relationship exists between financial literacy and innovative financial service adoption in Nigerian rural farming communities.

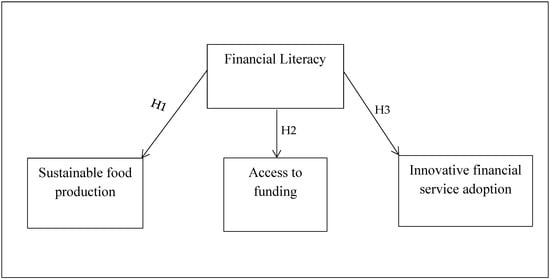

The study’s research model encapsulating the proposed research hypotheses is depicted in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1.

The research model.

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Procedure

The current study is a quantitative research study that relied on a cross-sectional survey design to collect quantitative primary data on financial literacy, sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative service adoption in Nigerian rural farming communities in Edo State, Nigeria [41]. The aim of adopting a quantitative research approach is to use numerical analysis to provide objective and generalisable findings of how financial literacy impacts sustainable food production, access to funding and innovative financial service adoption among rural Nigerian farmers [2,3]. The population of the study comprised the registered smallholder farmers in the Central Bank of Nigeria’s Anchored Borrower’s Programme. The Taro Yarmene’s [42] method for sample size determination was used to calculate the sample, and this resulted in a sample size of 400. The random sample size was increased by 20% to forestall the envisaged high number of unreturned and invalid questionnaires based on the rural nature of the respondents, and this brought the total sample size to 480.

Data Collection

We recruited research assistants who helped with interpreting and explaining the questionnaire items to some of the rural farmers who had difficulty understanding the English language. The research assistants were recruited based on their ability to understand the items in the questionnaire and the local languages of the respondents. The questionnaire was administered to the rural farmers on market days and Sundays in the localities, when most of the farmers do not go to their farms. The structured questionnaire was administered to the respondents in person. An introductory letter was sent along with the questionnaire that duly explained to the respondents the objective and nature of the study, as well as assurances of anonymity and confidentiality of their responses to the questions. All the respondents freely gave their consent and participated in the study. We eliminated the incidence of unreturned copies of the questionnaire by encouraging the respondents to answer and drop the questionnaire in the interview locations. This became necessary based on the interpretation assistance required by the respondents occasioned by low educational backgrounds and the difficult terrain of the rural areas. However, during sorting and coding, we found 15 copies of the questionnaire to be invalid due to self-contradicting answers.

3.2. Measures

The study adapted the “Standard and Poor Global Financial Literacy Questionnaire” developed by scholars at the World Bank Development Research Group and the George Washington University School of Business [43] to measure financial literacy. The scale measures financial literacy level in four dimensions, namely, “risk diversification, inflation, numeracy (interest), and compound interest”. We used the questionnaire because it was successfully used in past research to measure financial literacy among rural farmers [13]. We chose subjective measures of the financial literacy variable rather than using quantitative financial figures to measure financial literacy among the respondents because objective measures of financial literacy (i.e., the use of financial figures) are not ideal to be used among rural farmers due to the prevalence of poor recordkeeping among them [16].

Sustainable food production in Edo State rural farming communities was measured with an adapted scale from the work of de Carvalho et al. [44]. We adapted the scale, as Edo State is 1 of 36 states in Nigeria, and it is documented that the scale that measures sustainable food production systems at the national or global level is not suitable for measuring sustainable food production at subnational levels due to the unavailability of data for many indicators at the subnational level [44]. The constructs for measuring innovative financial service adoption were adapted from the works of Swiecka et al. [1] and Swiecka et al. [17], which measured the choice of payment among Polish consumers. Questions were asked about the present payment methods adopted by the farmers as well as their preferred payment method. The “subjective measure of access to finance” was adapted in the work of Fowowe [16] to measure access to agricultural funding. The statements include “I always have access to loans for my farm business”, “I always have the collateral security to obtain loans”, and “I get loans easily because I do not default in paying back”.

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Demographic Statistics

The analysis of the demographic profile of the farmers indicates that males dominate rural farming, as expected (391 or 85%), with the number of females standing at 69 (15%). The number of female rural farmers who were either divorced or separated was 61, or 13.3%, while those who were widowed stood at 16, or 3.5% (see Table 1). The outcomes indicate that rural farming is dominated by young adults, as the number of respondents in their 30s was 129 (27.6%), while the number of those in their 40s was 187 (40%). The number of farmers in their 50s was only 49 or 10.7%, and this low number could be explained by the use of energy-sapping crude farm implements, which is still predominant in African rural farming (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Respondents.

Results from the demographic analysis further indicate that the majority of the farmers (202 or 43.9%) possess secondary education, while 96 (20.9%) possess primary education, with 44 (9.6%) having no formal education. The low number of Nigerian rural farmers without formal education registered in the Central Bank of Nigeria’s Anchored Borrower’s Programme suggests that the majority of the farmers are being excluded from the credit scheme, as the majority of rural farmers are not literate [2,7,8].

Common Method Bias: Harman’s single-factor test is a statistical technique for identifying common method bias (CMB) in datasets; it is especially pertinent when data are gathered through self-report questionnaires. By determining whether a single component accounts for significant variance, the single-component test can detect any common method bias in the data. The cumulative variance explained by the first component, 15.989%, further supports the conclusion that multiple factors contribute to the structure of the data—a single factor typically needs to explain at least 50% of the variance to indicate a potential standard method bias issue. The first component in this dataset has an eigenvalue of 6.237, explaining 15.989% of the total variance, a relatively low percentage, suggesting a single factor does not dominate the dataset’s variance (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Harman’s single-factor test.

4.2. Measurement Model Evaluation

The measurement evaluation results depicted in Table 3 indicate that the factor loading of each variable’s specific items is greater than the recommended benchmark of 0.70. The average variance extracted estimate (AVE) results also support the instrument’s validity. For example, the AVE coefficients for financial literacy, sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption are 0.770, 0.645, 0.835, and 0.856, respectively, which exceed the recommended 0.50 threshold [45]. The instrument’s reliability was assessed with both composite reliability and Cronbach’s alpha. The composite reliability for financial literacy, sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption is 0.950, 0.849, 0.829, and 0.966, all of which are higher than the 0.70 benchmark. Cronbach’s alpha values for financial literacy, sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption are 0.934, 0.725, 0.884, and 0.949, respectively. The composite reliability values and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients are all significantly higher than the 0.70 threshold, indicating internal consistency [46]. The result from the variance inflation factor (VIF) analysis shows that all factor-level VIFs from the collinearity test are less than 3.3, an indication that the model is free from common method bias [47].

Table 3.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

The discriminant validity of the constructs was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations method, as displayed in Table 4. The results show that the upper confidence intervals are below 1, while all the HTMT values are different from 1, significantly indicating that the constructs are free from discriminate validity concerns. Also, the obtained HTMT values are below the critical value of the HTMT threshold of 0.85, suggesting that discriminate validity is established (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Discriminant validity.

The model fit analysis was performed using three categories of model fit indices, which are absolute, incremental, and parsimony fit measures (see Table 5). The absolute fit indices evaluate the accurate alignments of the sample data with the model’s theoretical predictions. The SRMR value of 0.077 is below the 0.08 threshold, indicating an acceptable fit. The GFI value of 0.931 also surpassed the recommended 0.90 cut-off, while the CMIN/DF ratio of 2.644 is less than the acceptable limit of 3.0, confirming model adequacy. Incremental fit indices assess the model’s improvement over a null model where variables are uncorrelated. The NFI value of 0.922 and other indices, such as the CFI of 0.940, exceeded the 0.90 benchmark, supporting a satisfactory fit. Parsimony fit indices, which evaluate model efficiency, showed a PCFI value of 0.625, above the 0.50 threshold. Also, the SRMR value of 0.077 falls within the acceptable range. The model’s overall validity was further supported by the d_ULS and d_G discrepancy measures, indicating a robust fit with the data [41,46,47].

Table 5.

Model fit.

4.3. Test of Hypotheses

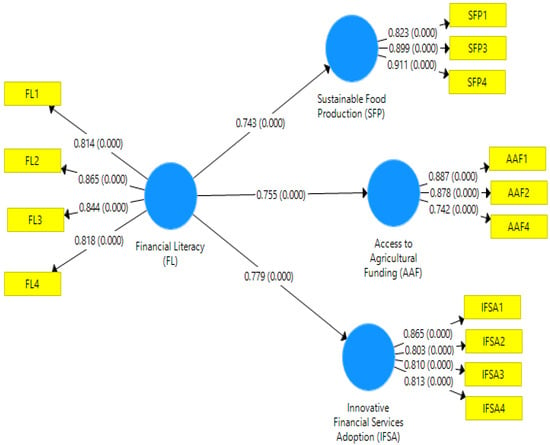

The proposed hypotheses were tested with partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) analysis, and the results are depicted in Figure 2 and Table 6. The independent variable is financial literacy, while sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption are the dependent variables. The decisions on the proposed hypothesis were taken based on path coefficient values, T-values, R-squared values, and p-values [41,46].

Figure 2.

Financial literacy and sustainable food production model.

Table 6.

Path coefficients for financial literacy and sustainable food production in rural Nigeria.

The results from H1 analysis show that financial literacy has a significant positive relationship with sustainable food production among rural Nigerian farmers (β = 0.743, T-value = 9.938 > 1.96, R2 = 0.552, and p-value = 0.000 < 0.05). The R2 value of 0.552 shows that financial literacy explains 55.2% of the variation in sustainable food production. The T-statistic of 9.938 and a p-value of 0.000 confirm the statistical significance of this relationship between financial literacy and sustainable food production among the farmers.

The outcomes further suggest in H2 analysis that a positive significant relationship exists between financial literacy and access to agricultural funding (β = 0.755, T-value = 11.782 > 1.96, R2 = 0.571, and p-value = 0.000 < 0.05). The R2 value of 0.571 suggests that financial literacy explains 57.1% of the variance in access to funding. The T-statistic of 11.782 and a p-value of 0.000 also confirm that this relationship is statistically significant.

Also, the path from financial literacy to the adoption of innovative financial services captured in H3 suggests a significant positive relationship between the two variables (β = 0.779, T-value = 15.071 > 1.96, R2 = 0.607, and p-value = 0.000 < 0.05). An R2 value of 0.607 implies that financial literacy accounts for 60.7% of the variance in the adoption of such services among the rural farmers. The high T-statistic of 15.071 and the p-value of 0.000 indicate a strong and significant relationship between the two variables.

5. Discussion of Findings

Following the frequent innovative and complex nature of financial products and services that resulted in the calls for research into financial literacy, particularly among rural farmers in developing countries [10,12,13], the current study assesses how financial literacy influences sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption among rural farmers, who are the most vulnerable group in Nigeria. The outcomes in hypothesis 1 indicate that financial literacy significantly predicts sustainable food production among rural farmers. This aligns with similar previous research that reported that financial management skills influence higher performance [6,26]. The reason why rural farmers in Edo State in Nigeria are able to use their financial literacy to influence production may be their ability to identify and effectively utilise viable financial products and services, such as borrowing opportunities to acquire modern farm inputs to improve productivity and earnings. This also suggests that rural farmers’ financial knowledge increases their productivity through sound financial management of the available resources. This is an indication that Nigerian rural farmers who possess adequate financial literacy are able to understand the terms and conditions of the loans and invest the loans wisely in their farming ventures.

The outcomes in hypothesis 2 show that financial literacy significantly predicts access to credit funding among rural farmers. We found congruence between this current outcome and the work of [34] that found a significant positive link between financial literacy and access to formal credit facilities among business owners in China. The result also conforms to findings by Twumasi et al. [6] that suggest that financial literacy directly predicts access to financial services among households in rural Ghana. The financial knowledge to identify the sources of loans and understand the associated conditionality may account for the ability of rural farmers to have more access to credit for their farming business. Understanding modern financial products and services increases savings, which lays a solid foundation for accessing loans from financial institutions. Another reason why financial literacy significantly predicts access to credit among the farmers may be that financial knowledge equips rural farmers with better risk management, which minimises loan repayment defaults and increases the chances for future loans.

The proposed H3 was confirmed, indicating a significant relationship between financial literacy and adoption of innovative financial services among rural farmers. This outcome suggests that the more financially literate a rural farmer is, the better the choice of mode of payment (digital payment) the farmer will make. This result is in line with studies conducted in Canada [36] and Poland [17] that reported that financial literacy predicts payment choices among consumers. The reason why adoption of innovative financial services is influenced by financial literacy among rural farmers may be that the financially literate ones are able to understand the benefits of adopting modern payment methods, such as the absence of theft/robbery of cash. For example, mobile phone payment eliminates the incidence of theft/robbery of cash, and the transaction is very convenient.

5.1. Theoretical Implication of Findings

The positive influence of financial literacy on sustainable food production, access to agricultural funding, and adoption of innovative financial services for rural farmers has many theoretical implications. First, this study makes significant contributions to the financial literacy literature by deploying a microeconomic framework to provide insights into how financial literacy impacts sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption in the Nigerian context. The theory suggests that rational and well-informed individuals make informed and profitable financial decisions [18].

Second, this study fills an important gap in the literature by responding to the calls by researchers for studies on financial literacy [11,12], which poses a big challenge for economic development [12]. For example, previous studies noted that in spite of the important place of financial literacy, particularly in sustaining and improving rural farming, current studies have observed that little is known about financial literacy in the literature, particularly in rural communities in developing countries [2,9].

Third, this current study contributes to sustainable production literature in African rural areas by shifting research focus from the dominant topic of agricultural financing of large-scale agro-allied industries to the neglected role of financial literacy in rural farming business sustainability. As attested to by Matewos et al. [14], continued lack of adequate financial literacy knowledge in developing African countries impedes the effective formulation and implementation of financial policies and programmes.

5.2. Practical Implications of Findings

The outcomes of this study have important policy implications for government and financial authorities.

First, the current findings on Nigerian rural farmers’ adoption of innovative financial services through financial literacy could guide the government and financial authorities in formulating financial inclusion policies that will further broaden the utilisation of financial literacy as a tool to realise economic development objectives in other sectors of the economy. Second, the positive link found between financial literacy, access to funding, and sustainable food production in rural farming communities might motivate the government to initiate strategies to improve financial literacy in rural areas for sustainable food production. This can be achieved by the government by heightening public enlightenment campaigns on financial literacy through the mass media.

Third, at the individual level, the outcomes of this study will motivate rural Nigerian farmers to improve and sustain adequate financial literacy levels by attending training, seminars, and workshops on financial literacy, as this study has shown that such knowledge is capable of helping them adopt innovative financial services, gain access to agricultural funding opportunities, and achieve sustainable food production levels. Fourth, the financial literacy knowledge acquired by the rural farmers is important for navigating the ever-changing and complex financial landscape, making informed financial decisions, and increasing their overall well-being.

5.3. Research Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Although this study makes important contributions to the sustainability literature by investigating how financial literacy impacts sustainable food production, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption among rural Nigerian farmers, it is crucial to point out its limitations and suggest possible areas for future research. First, the current study utilised a cross-sectional research design, which is handicapped in establishing causality among the variables investigated. To address this challenge, future research may consider using a longitudinal design. Second, this study did not explore gender differences in how financial literacy relates to sustainable food products, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption among rural Nigerian farmers. We believe that it will be of great importance if comparative studies are conducted by researchers to provide understanding of gender differences in how financial literacy relates to sustainable food products, access to funding, and innovative financial service adoption among rural Nigerian farmers. Third, data were collected from the respondents through a self-report approach. Therefore, chances are that the respondents might have either downplayed or exaggerated their financial literacy levels and how they impact their farming activities, access to funding, and adoption of formal financial services. To address this limitation, we suggest that future researchers may consider using secondary data where possible, rather than directly collecting primary data from the farmers.

5.4. Conclusions

This study concludes that financial literacy significantly predicts sustainable food production, access to agricultural funding, and adoption of innovative financial services in rural farming communities in Nigeria. This contribution to the development of rural farming in Nigeria is important as it shifts research attention from the dominant topics of diversification, land use, agricultural policies/programmes, and agricultural loans for large-scale agro-allied industries to the neglected area of financial literacy among rural farmers.

The findings of this study suggest the need for the Nigerian government and financial authorities to formulate financial inclusion policies that will further broaden the utilisation of financial literacy as a tool to realise economic development objectives in other sectors of the economy. The study suggested areas where future studies could address the limitations of this study. This includes the adoption of a longitudinal design to address the study’s limitation of relying on a cross-sectional research design and the evaluation of gender differences in how financial literacy impacts rural farmers, which the current study did not cover.

Author Contributions

Data curation, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; formal analysis, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; funding acquisition, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; investigation, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; methodology, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; project administration, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; resources, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; software, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; supervision, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; validation, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; visualisation, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; writing—original draft, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A.; writing—review and editing, B.O.I. and E.N.N.-A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki declaration guidelines and was also approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Management, University of Nigeria, Enugu Campus (protocol code: DM-2024-064; date of approval: 15 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed in the current study are not publicly available because of the ongoing research and analysis but are, however, available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Świecka, B.; Terefenko, P.; Wiśniewski, T.; Xiao, J.J. Consumer financial knowledge and cashless payment behavior for sustainable development in Poland. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obi-Anike, H.O.; Daniel, O.C.; Onodugo, I.J.; Attamah, I.J.; Imhanrenialena, B.O. The Role of Financial Information Literacy in Strategic Decision-Making Effectiveness and Sustainable Performance among Agribusiness Entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoso, W.; Asmara, K.; Abidin, Z. Measuring the financial literacy of farmers food crops in the poor area of Madura, Indonesia. Eur. J. Agric. Food Sci. 2020, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safitri, K.A. An analysis of Indonesian farmer’s financial literacy. Stud. Appl. Econ. 2021, 39, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. How ordinary consumers make complex economic decisions: Financial literacy and retirement readiness. Q. J. Financ. 2017, 7, 1750008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, M.A.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Wang, P.; Abgenyo, W. The mediating role of access to financial services in the effect of financial literacy on household income: The case of rural Ghana. Sage Open 2022, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhanrenialena, B.O.; Obi-Anike, O.H.; Okafor, C.N.; Ike, R.N.; Obiora Okafo, C. Addressing financial inclusion challenges in rural areas from the financial services marketing employee emotional labor dimension: Evidence from Nigeria. J. Financ. Serv. Mark. 2021, 27, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imhanrenialena, B.O.; Obi-Anike, O.H.; Okafor, C.N.; Ike, R.N. Potential for indigenous communication systems to improve financial literacy: Evidence from Nigeria. Enterp. Dev. Microfinanc. 2021, 32, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbemudia, I.; Benedict, E.W.; Ugwu, C.N.; Ibe, C.B. Investing in Rural Agriculture in the Face of Innovative Financial Services: Does Financial Literacy Matter in Nigeria? SAGE Open 2024, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conrad, M.; Gamuchirai, M.; Pepukai, P.C.; Rumbidzai, M. Financial inclusion, nutrition and socio-economic status among rural households in Guruve and Mount Darwin districts, Zimbabwe. J. Int. Dev. 2020, 33, 86–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, K.; Kumar, S. Financial literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 80–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riaz, S.; Khan, H.H.; Sarwar, B.; Ahmed, W.; Muhammad, N.; Reza, S.; Haq, S.M.N.U. Influence of financial social agents and attitude toward money on financial literacy: The mediating role of financial self-efficacy and moderating role of mindfulness. Sage Open 2022, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, S.K.; Laha, A. Financial literacy and its antecedents amongst the farmers: Evidence from India. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2022, 83, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matewos, K.R.; Navkiranjit, K.D.; Jasmindeep, K. Financial literacy for developing countries in Africa: A review of concept, significance and research opportunities. J. Afr. Stud. Dev. 2016, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twumasi, M.A.; Jiang, Y.; Adhikari, S.; Adu Gyamfi, C.; Asare, I. Financial literacy and its determinants: The case of rural farm households in Ghana. Agric. Financ. Rev. 2022, 82, 641–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowowe, B. Access to finance and firm performance: Evidence from African countries. Rev. Dev. Financ. 2017, 7, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiecka, B.; Terefenko, P.; Paprotny, D. Transaction factors’ influence on the choice of payment by Polish consumers. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The Economic Importance of Financial Literacy: Theory and Evidence; Working Paper Series No. 2014-001; Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center (GFLEC): Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Delavande, A.; Rohwedder, S.; Willis, R. Preparation for Retirement, Financial Knowledge and Cognitive Resources; WP2008-190; Michigan Retirement Research Center, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jappelli, T.; Padula, M. Investment in financial literacy and saving decisions. J. Bank. Financ. 2013, 37, 2779–2792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States. J. Pension Econ. Financ. 2011, 10, 509–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernheim, D. Financial illiteracy, education, and retirement saving. In Living with Defined 22. Contribution Pensions; Mitchell, O.S., Schieber, S., Eds.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1998; pp. 38–68. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, S.; Driscoll, J.; Gabaix, X.; Laibson, D. The age of reason: Financial decisions over the lifecycle with implications for regulation. Brook. Pap. Econ. Act. 2009, 2009, 51–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C. Financial Illiteracy and Pension Contributions: A Field Experiment on Compound Interest in China; Berkeley Working Paper; University of California: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Koomson, I.; Villano, R.A.; Hadley, D. Effect of financial inclusion on poverty and vulnerability to poverty: Evidence using a multidimensional measure of financial inclusion. Soc. Indic. Res. 2020, 149, 613–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Gaudecker, H.-M. How does household portfolio diversification vary with financial literacy and financial advice? J. Financ. 2015, 70, 489–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakora, A. Measuring the effectiveness of financial literacy programs in Ghana. Int. J. Manag. Bus. Res. 2016, 3, 135–148. [Google Scholar]

- Paltasingh, K.R.; Goyari, P. Impact of farmer education on farm productivity under varying technologies: Case of paddy growers in India. Agric. Food Econ. 2018, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A.; Mitchell, O.S. The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. J. Econ. Lit. 2013, 52, 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bucher-Koenen, T.; Lusardi, A.; Alessie, R.J. How financially literate are women? An overview and new insights. J. Consum. Aff. 2016, 51, 255–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klapper, L.F.; Lusardi, A.; Panos, A. Financial Literacy and the Financial Crisis; Working Paper 17930; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w17930 (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Lusardi, A.; Tufano, P. Debt Literacy, Financial Experiences, and Over Indebtedness; Working Paper 14808; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bank Indonesia. Financial Inclusion Booklet; Department of Development Financial Access and Small and Medium Enterprises: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014.

- Xu, N.; Shi, J.; Rong, Z.; Yuan, Y. Financial literacy and formal credit accessibility: Evidence from informal businesses in China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2020, 36, 101327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widhiyanto, I.; Nuryartono, N.; Harianto, H.; Siregar, H. The analysis of farmers’ financial literacy and its impact on microcredit accessibility with interest subsidy on agricultural sector. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Issues 2018, 8, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C.S.; Huynh, K.P.; Welte, A. Method-of-Payments Survey Results; Staff Discussion Paper 2018-17; Bank of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Robb, C.A. Financial knowledge and credit card behavior of college students. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2011, 32, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Anderson, S.; Seay, M. Financial knowledge and short-term and long-term financial behaviours of millennials in the United States. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2018, 40, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuwono, M.; Suharjo, B.; Sanim, B.; Nurmalina, R. Analisis deskriptif atas literasi keuangan pada kelompok tani. Ekuinas J. Ekon. Keuang. 2017, 1, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Otoritas, J.K. Survey on Indonesian Financial Literacy Index Survey; OJK: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.; Risher, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis, 2nd ed.; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Klapper, L.; Lusardi, A.; van Oudheusden, P. The Standard and Poor Global Financial Literacy Survey; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.FinLit.MHFI.com (accessed on 21 September 2021).

- de Carvalho, A.M.; Verly, E., Jr.; Marchioni, D.M.; Jones, A.D. Measuring Sustainable Food Systems in Brazil: A Framework and Multidimensional Index to Evaluate Socioeconomic, Nutritional, and Environmental Aspects. World Dev. 2021, 143, 105470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, A.H.; Rahman, I.A. SEM-PLS analysis of inhibiting factors of cost performance for large construction projects in Malaysia: Perspective of clients and consultants. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 165158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. Using partial least squares path modeling in advertising research: Basic concepts and recent issues. In Handbook of Research on International Advertising; Okazaki, S., Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kock, N. One-tailed or two-tailed P values in PLS-SEM? Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).